Examination of In Vivo Mutations in VP4 (VP8*) of the Rotarix® Vaccine from Shedding of Children Living in the Amazon Region

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Control Sampling

2.3. Extraction of Total Nucleic Acids and qRT-PCR to Detect Rotavirus

2.4. Specific qRT-PCR to Distinguish Wild-Type RVA G1P[8] Samples from Those Derived from Vaccine (Rotarix®)

2.5. PCR Amplification and Nucleotide Sequencing of the VP4 (VP8*) and VP7 Genes of Vaccine (Rotarix®) Samples

2.6. Phylogenetic Trees, G1P[8] Designation, and Statistical Analysis

2.7. In Silico Structural Modeling and Docking of the VP4 Protein (VP8* Domain) with HBGA Sugars

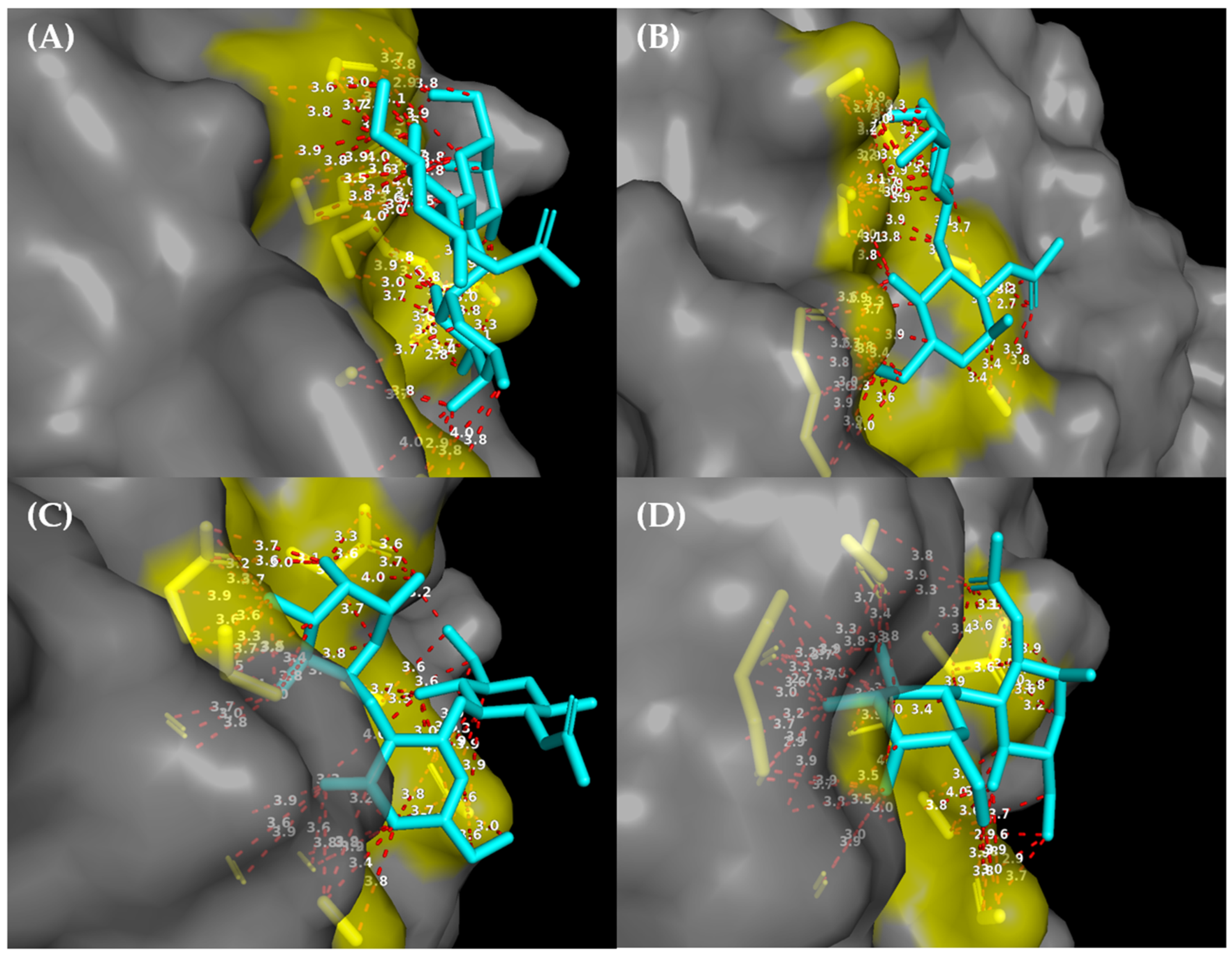

Structural Refinement of Protein–Sugar Interactions and Estimation of Atomic Proximity at the Binding Site

2.8. Secretor Status and Lewis Antigen Phenotyping

3. Results

3.1. Low Frequency of RVA Detection During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Children Living in the Amazon Region

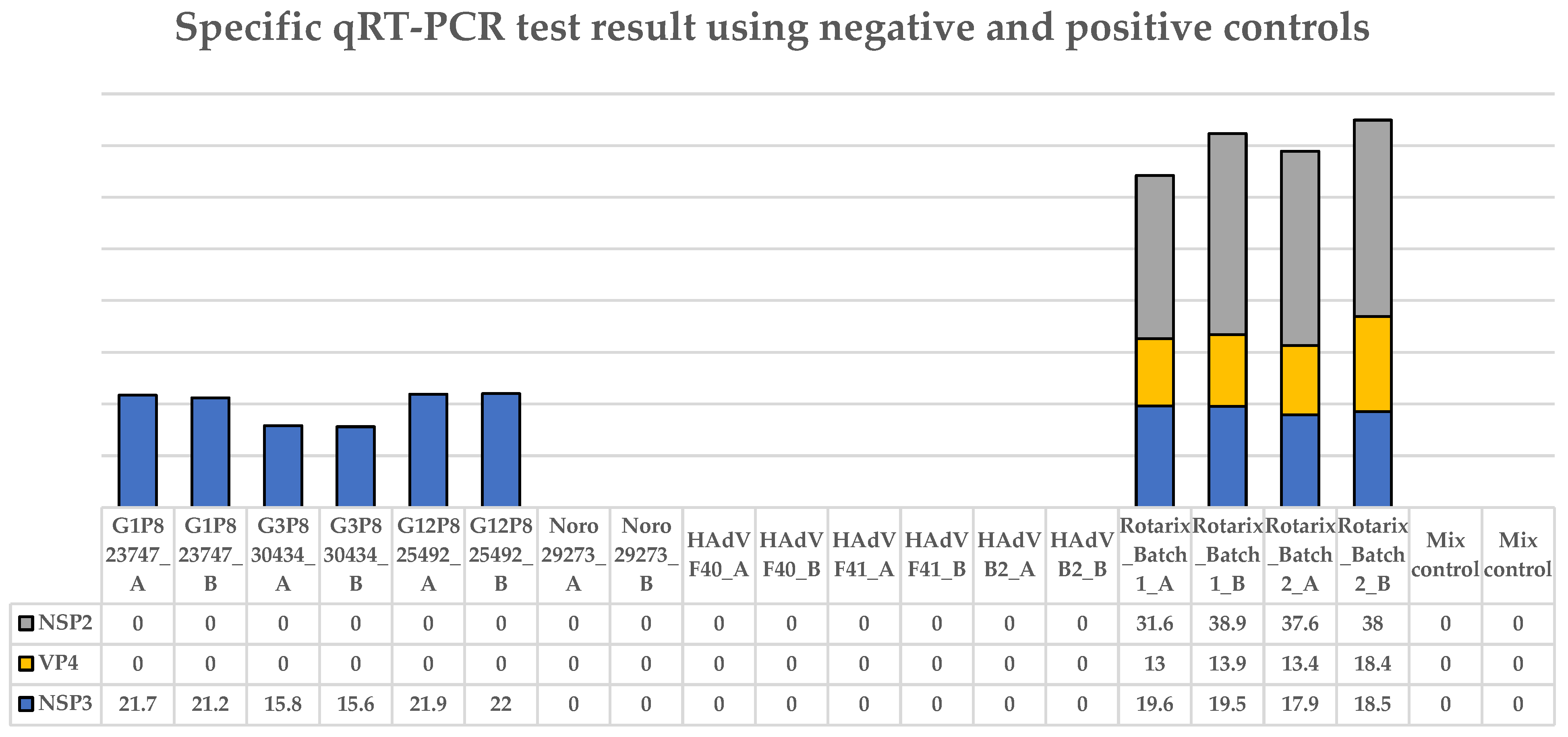

3.2. The Specific qRT-PCR Distinguished Wild-Type RVA, Human Adenovirus, and Norovirus Controls from Vaccine (Rotarix®)

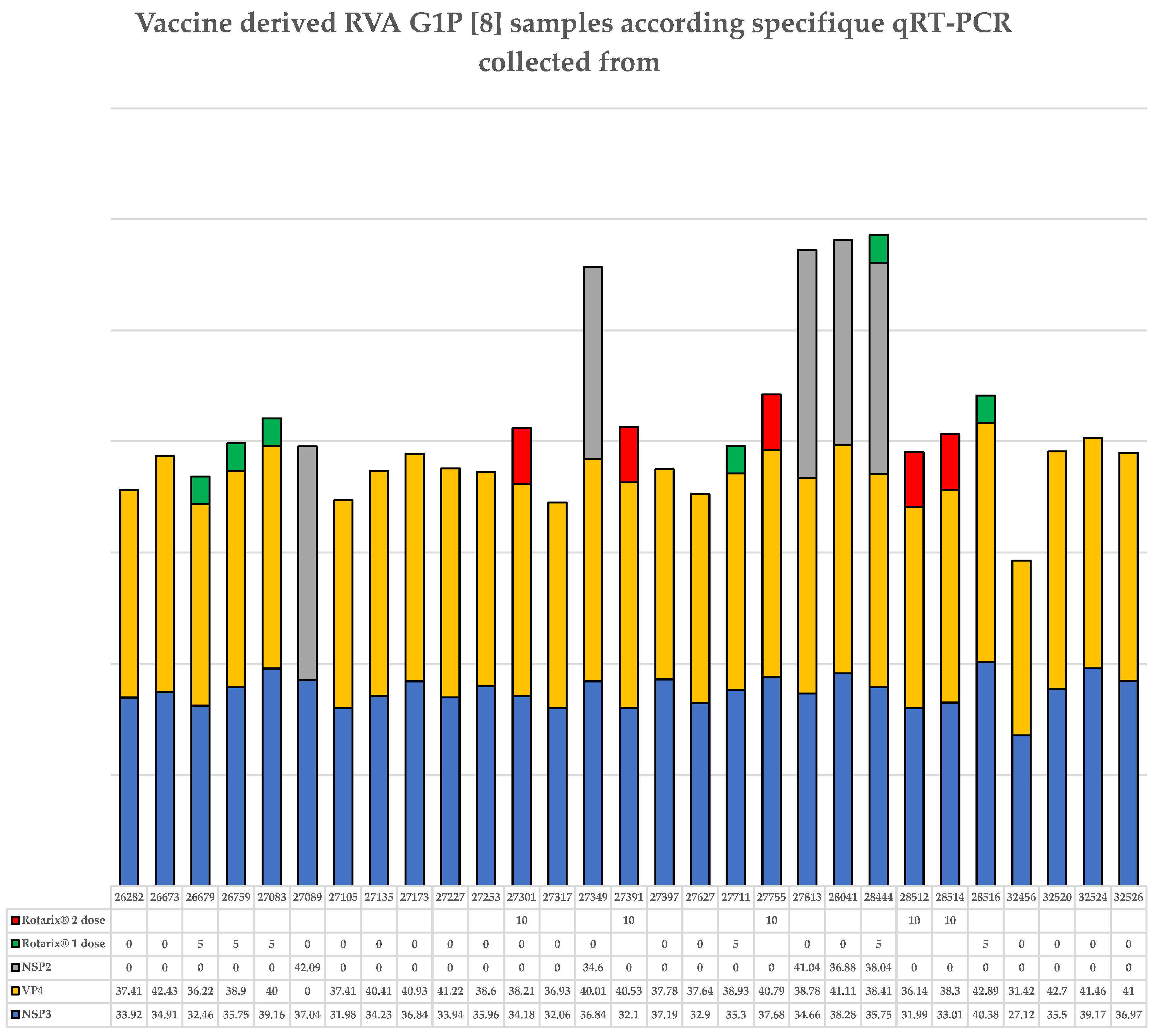

3.3. Children Not Vaccinated with the Rotarix® Vaccine Who Live in the Amazon Region Eliminate Rotarix® G1P[8] Vaccine

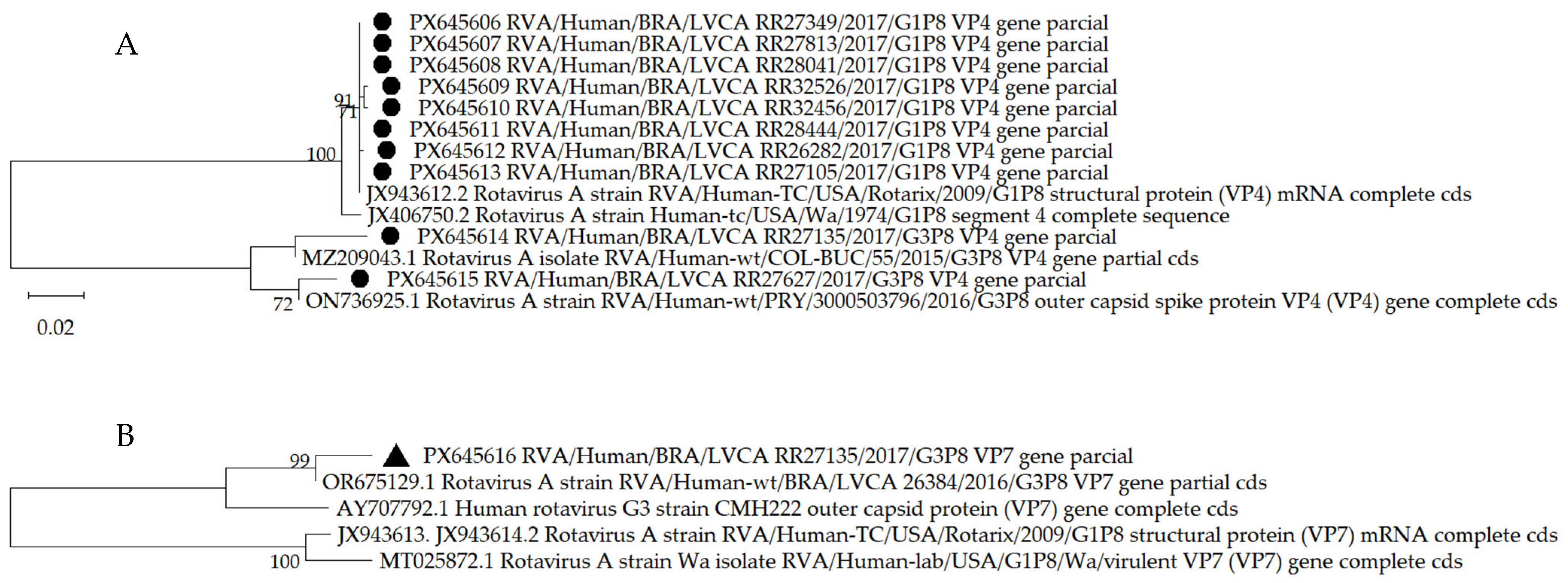

3.4. The VP4 (VP8*) Gene of the Rotarix® Vaccine Shedding from Children Living in the Amazon Region Exhibits Point Mutations

3.5. In Silico Analysis of the Mutations Showed No Impact on the Protein Structure of VP8* Rotarix® Mutants

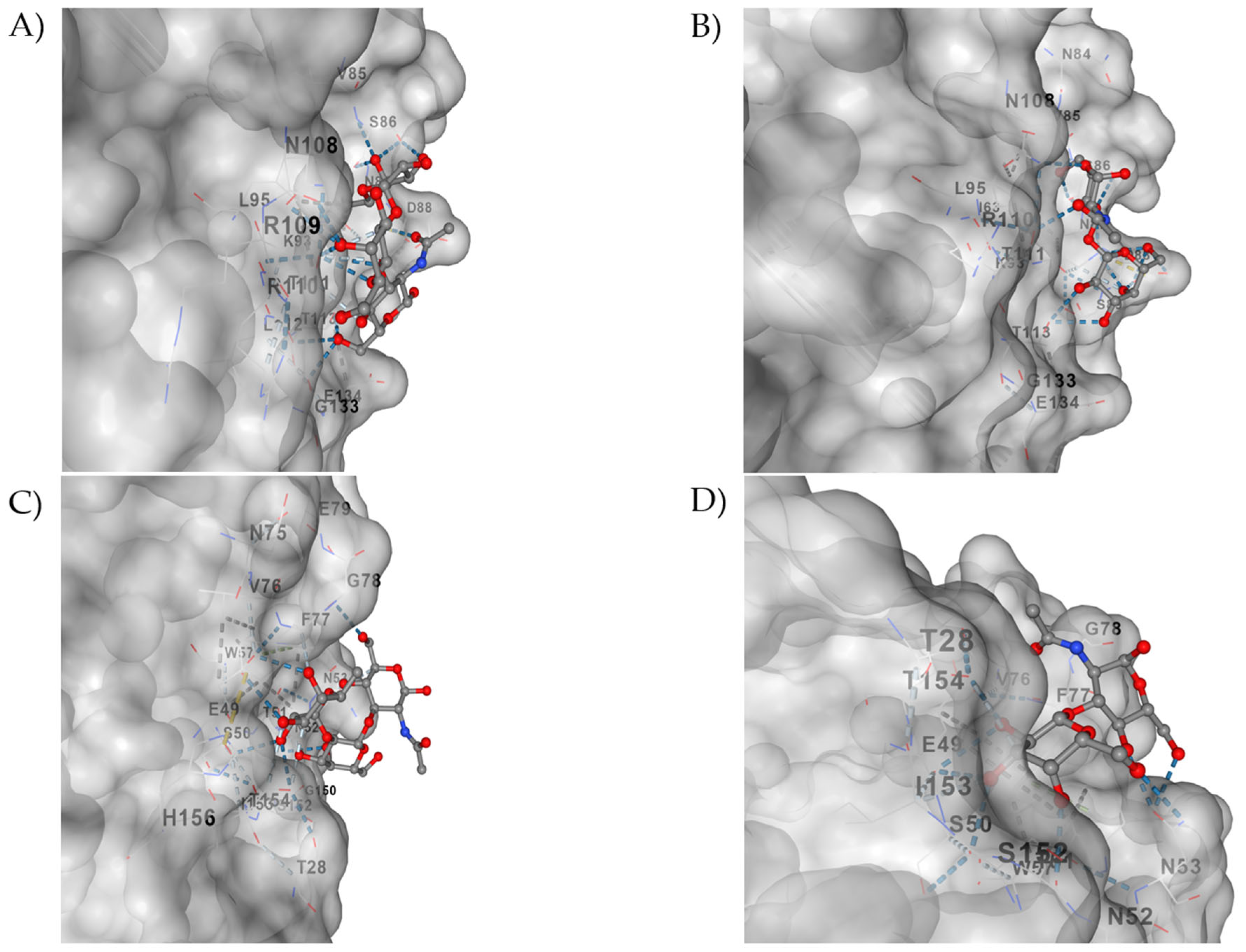

3.6. In Silico Interactions of the VP4 (VP8*) Protein from the Rotarix G1P Vaccine [8] and the Wild Type with the Sugars H1- and Lacto-N-Biose Are Similar

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGE | Acute Gastroenteritis |

| Ct | Cycle Threshold |

| DOAJ | Directory of Open-Access Journals |

| dsRNA | Double-Stranded RNA |

| EIA | Enzyme Immunoassay |

| Fiocruz | Oswaldo Cruz Foundation |

| FUT2 | Fucosyltransferase 2 |

| HAdV | Human Adenovirus |

| HBGA | Histo-Blood Group Antigen |

| HCSA | Hospital da Criança de Santo Antônio |

| IOC | Instituto Oswaldo Cruz |

| LNB | Lacto-N-biose |

| LVCA-RRRL | Laboratory of Comparative and Environmental Virology–Regional Rotavirus Reference Laboratory |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PDB | Protein Data Bank |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR |

| RV | Rotavirus |

| RVA | Rotavirus A |

| SDF | Structural Data File |

| TLA | Three-Letter Acronym |

References

- Desselberger, U. Rotavirus. Virus Res. 2014, 190, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, Y.A.; Yolken, R.H. Rotavirus. Bailliere’s Clin. Gastroenterol. 1990, 4, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, U.D.; Nelson, E.A.; Kang, G. Diagnosis, management, and prevention of rotavirus gastroenteritis in children. BMJ 2013, 30, f7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, S.K.; Ko, D.H.; Hyun, J.; Kim, H.S. Performance Evaluation of the Automated Fluorescent Immunoassay System Rotavirus Assay in Clinical Samples. Ann. Lab. Med. 2019, 39, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivares, A.I.O.; Leitão, G.A.A.; Pimenta, Y.C.; Cantelli, C.P.; Fumian, T.M.; Fialho, A.M.; da Silva, E.M.S.J.; Delgado, I.F.; Nordgren, J.; Svensson, L.; et al. Epidemiology of enteric virus infections in children living in the Amazon region. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 108, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, N.S.; Mendes, I.B.R.; Morais, C.G.; Celere, B.S.; Meschede, M.S.C. Vaccination coverage of rotavirus and Hepatitis A in a region of the Amazon without satisfactory sanitation. Vigil. Sanit. Debate Rio J. 2025, 13, e02284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, T.; Borrow, R.; Arkwright, P.D. Impact of rotavirus vaccination on diarrheal disease burden of children in South America. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2024, 23, 606–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, H.B.; Estes, M.K. Rotaviruses: From Pathogenesis to Vaccination. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthijnssens, J.; Ciarlet, M.; Rahman, M.; Attoui, H.; Bányai, K.; Estes, M.K.; Gentsch, J.R.; Iturriza-Gómara, M.; Kirkwood, C.D.; Martella, V.; et al. Recommendations for the classification of group A rotaviruses using all 11 genomic RNA segments. Arch. Virol. 2008, 153, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthijnssens, J.; Ciarlet, M.; McDonald, S.M.; Attoui, H.; Bányai, K.; Brister, J.R.; Buesa, J.; Esona, M.D.; Estes, M.K.; Gentsch, J.R.; et al. Uniformity of rotavirus strain nomenclature proposed by the Rotavirus Classification Working Group (RCWG). Arch. Virol. 2011, 156, 1397–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, C.F.; Romero, P.; Alvarez, V.; López, S. Trypsin activation pathway of rotavirus infectivity. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 5832–5839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, N.; Feng, N.; Blum, L.K.; Sanyal, M.; Ding, S.; Jiang, B.; Sen, A.; Morton, J.M.; He, X.S.; Robinson, W.H.; et al. VP4- and VP7-specific antibodies mediate heterotypic immunity to rotavirus in humans. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaam5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.M.; Matthijnssens, J.; McAllen, J.K.; Hine, E.; Overton, L.; Wang, S.; Lemey, P.; Zeller, M.; Van Ranst, M.; Spiro, D.J.; et al. Evolutionary dynamics of human rotaviruses: Balancing reassortment with preferred genome constellations. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkwood, C.D. Genetic and antigenic diversity of human rotaviruses: Potential impact on vaccination programs. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 202, S43–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, J.T. Rotavirus diversity and evolution in the post-vaccine world. Discov. Med. 2012, 13, 85–97. [Google Scholar]

- Dormitzer, P.; Nason, E.; Venkataram Prasad, B.V.; Harrison, S.C. Structural rearrangements in the membrane penetration protein of a non-enveloped virus. Nature 2004, 430, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Crawford, S.E.; Czako, R.; Cortes-Penfield, N.W.; Smith, D.F.; Le Pendu, J.; Estes, M.K.; Prasad, B.V.V. Cell attachment protein VP8* of a human rotavirus specifically interacts with A-type histo-blood group antigen. Nature 2012, 485, 256–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, D.; Duan, Z. Structural basis of glycan recognition of rotavirus. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 658029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, S.T.; Settembre, E.C.; Trask, S.D.; Greenberg, H.B.; Harrison, S.C.; Dormitzer, P.R. Structure of rotavirus outer-layer protein VP7 bound with a neutralizing Fab. Science 2009, 324, 1444–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staat, M.A.; Azimi, P.H.; Berke, T.; Roberts, N.; Bernstein, D.I.; Ward, R.L.; Pickering, L.K.; Matson, D.O. Clinical presentations of rotavirus infection among hospitalized children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2002, 21, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, X.; Tao, Y.; Wang, B.; Hou, Y.; Ning, Y.; Hou, J.; Wang, R.; Li, Q.; Xia, X. Diversity and Potential Cross-Species Transmission of Rotavirus A in Wild Animals in Yunnan, China. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianiro, G.; Di Bartolo, I.; De Sabato, L.; Pampiglione, G.; Ruggeri, F.M.; Ostanello, F. Detection of uncommon G3P [3] rotavirus A (RVA) strain in rat possessing a human RVA-like VP6 and a novel NSP2 genotype. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017, 53, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyaga, M.M.; Jere, K.C.; Peenze, I.; Mlera, L.; van Dijk, A.A.; Seheri, M.L.; Mphahlele, M.J. Sequence analysis of the whole genomes of five African human G9 rotavirus strains. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2013, 16, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dian, Z.; Wang, B.; Fan, M.; Dong, S.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, A.M.; Liu, L.; Niu, H.; Li, Y.; Xia, X. Completely genomic and evolutionary characteristics of human-dominant G9P[8] group A rotavirus strains in Yunnan, China. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 1163–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadiq, A.; Bostan, N.; Yinda, K.C.; Naseem, S.; Sattar, S. Rotavirus: Genetics, pathogenesis and vaccine advances. Rev. Med. Virol. 2018, 28, e2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoxie, I.; Dennehy, J.J. Intragenic recombination influences rotavirus diversity and evolution. Virus Evol. 2020, 6, vez059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, S.E.; Ramani, S.; Tate, J.E.; Parashar, U.D.; Svensson, L.; Hagbom, M.; Franco, M.A.; Greenberg, H.B.; O’Ryan, M.; Kang, G.; et al. Rotavirus infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Hagbom, M.; Svensson, L.; Nordgren, J. The Impact of Human Genetic Polymorphisms on Rotavirus Susceptibility, Epidemiology, and Vaccine Take. Viruses 2020, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, P.; Tan, M.; Liu, Y.; Biesiada, J.; Meller, J.; Castello, A.A.; Jiang, B.; Jiang, X. Rotavirus VP8*: Phylogeny, host range, and interaction with histo-blood group antigens. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 9899–9910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Esona, M.D.; Mijatovic-Rustempasic, S.; Ian Tam, K.; Gentsch, J.R.; Bowen, M.D. Real-time RT-PCR assays to differentiate wild-type group A rotavirus strains from Rotarix (®) and RotaTeq(®) vaccine strains in stool samples. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2014, 10, 767–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, N.S. Acute gastroenteritis. Prim. Care 2013, 40, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.Q.; Halkosalo, A.; Salminen, M.; Szakal, E.D.; Puustinen, L.; Vesikari, T. One-step quantitative RT-PCR for the detection of rotavirus in acute gastroenteritis. J. Virol. Methods 2008, 153, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmonds, M.K.; Armah, G.; Asmah, R.; Banerjee, I.; Damanka, S.; Esona, M.; Gentsch, J.R.; Gray, J.J.; Kirkwood, C.; Page, N.; et al. New oligonucleotide primers for P-typing of rotavirus strains: Strategies for typing previously untypeable strains. J. Clin. Virol. 2008, 42, 368–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómara, M.I.; Cubitt, D.; Desselberger, U.; Gray, J. Amino acid substitution within the VP7 protein of G2 rotavirus strains associated with failure to serotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 3796–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLano, W.L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System; DeLano Scientific: San Carlos, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Word, J.M.; Lovell, S.C.; LaBean, T.H.; Taylor, H.C.; Zalis, M.E.; Presley, B.K.; Richardson, J.S.; Richardson, D.C. Visualizing and quantifying molecular goodness-of-fit: Small-probe contact dots with explicit hydrogen atoms. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 285, 1711–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, I.W.; Leaver-Fay, A.; Chen, V.B.; Block, J.N.; Kapral, G.J.; Wang, X.; Murray, L.W.; Arendall, W.B., 3rd; Snoeyink, J.; Richardson, J.S.; et al. MolProbity: All-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W375–W383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, D.M.; Gohlke, H. DrugScorePPI webserver: Fast and accurate in silico alanine scanning for scoring protein–protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W480–W486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.R.; Schapira, M.A. systematic analysis of atomic protein-ligand interactions in the PDB. Medchemcomm 2017, 8, 1970–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Moraes, M.T.B.; Olivares, A.I.O.; Fialho, A.M.; Malta, F.C.; da Silva, E.M.S.J.; de Souza, B.R.; Velloso, A.J.; Alves, L.G.A.; Cantelli, C.P.; Nordgren, J.; et al. Phenotyping of Lewis and secretor HBGA from saliva and detection of new FUT2 gene SNPs from young children from the Amazon presenting acute gastroenteritis and respiratory infection. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 70, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordgren, J.; Sharma, S.; Bucardo, F.; Nasir, W.; Günaydın, G.; Ouermi, D.; Nitiema, L.W.; Becker-Dreps, S.; Simpore, J.; Hammarström, L.; et al. Both Lewis and secretor status mediate susceptibility to rotavirus infections in a rotavirus genotype-dependent manner. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 1567–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamrin, P.; Peerakome, S.; Wongsawasdi, L.; Tonusin, S.; Sornchai, P.; Maneerat, V.; Khamwan, C.; Yagyu, F.; Okitsu, S.; Ushijima, H.; et al. Emergence of human G9 rotavirus with an exceptionally high frequency in children admitted to hospital with diarrhea in Chiang Mai, Thailand. J. Med. Virol. 2006, 78, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, M.B.; de Assis, R.M.S.; Andrade, J.D.S.R.; Fialho, A.M.; Fumian, T.M. Rotavirus A during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brazil, 2020-2022: Emergence of G6P[8] Genotype. Viruses 2023, 15, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantelli, C.P.; Velloso, A.J.; Assis, R.M.S.; Barros, J.J.; Mello, F.C.D.A.; Cunha, D.C.D.; Brasil, P.; Nordgren, J.; Svensson, L.; Miagostovich, M.P.; et al. Rotavirus A shedding and HBGA host genetic susceptibility in a birth community-cohort, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2014–2018. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurgel, R.Q.; Cuevas, L.E.; Vieira, S.C.; Barros, V.C.; Fontes, P.B.; Salustino, E.F.; Nakagomi, O.; Nakagomi, T.; Dove, W.; Cunliffe, N.; et al. Predominance of rotavirus P[4]G2 in a vaccinated population, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 1571–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoni, S.; Nakamura, T.; Cohen, A.L.; Mwenda, J.M.; Weldegebriel, G.; Biey, J.N.M.; Shaba, K.; Rey-Benito, G.; de Oliveira, L.H.; Oliveira, M.T.D.C.; et al. Rotavirus genotypes in children under five years hospitalized with diarrhea in low and middle-income countries: Results from the WHO-coordinated Global Rotavirus Surveillance Network. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2023, 3, e0001358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, D.C.D.; Fuller, T.; Cantelli, C.P.; de Moraes, M.T.B.; Leite, J.P.G.; Carvalho-Costa, F.A.; Brasil, P. Circulation of Vaccine-derived Rotavirus G1P[8] in a Vulnerable Child Cohort in Rio de Janeiro. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicentini, F.; Denadai, W.; Gomes, Y.M.; Rose, T.L.; Ferreira, M.S.; Le Moullac-Vaidye, B.; Le Pendu, J.; Leite, J.P.; Miagostovich, M.P.; Spano, L.C. Molecular characterization of noroviruses and HBGA from infected Quilombola children in Espírito Santo State, Brazil. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, C.; Bloemen, M.; Jansen, D.; Descheemaeker, P.; Reynders, M.; Van Ranst, M.; Matthijnssens, J. Rotavirus vaccine-derived cases in Belgium: Evidence for reversion of attenuating mutations and alternative causes of gastroenteritis. Vaccine 2022, 40, 5114–5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozalbo-Rovira, R.; Ciges-Tomas, J.R.; Vila-Vicent, S.; Buesa, J.; Santiso-Bellón, C.; Monedero, V.; Yebra, M.J.; Marina, A.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J. Unraveling the role of the secretor antigen in human rotavirus attachment to histo-blood group antigens. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramani, S.; Hu, L.; Venkataram Prasad, B.V.; Estes, M.K. Diversity in Rotavirus-Host Glycan Interactions: A “Sweet” Spectrum. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 2, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Xia, M.; Tan, M.; Zhong, W.; Wei, C.; Wang, L.; Morrow, A.; Jiang, X. Spike protein VP8* of human rotavirus recognizes histo-blood group antigens in a type-specific manner. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 4833–4843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Coulson, B.S.; Fleming, F.E.; Dyason, J.C.; von Itzstein, M.; Blanchard, H. Novel structural insights into rotavirus recognition of ganglioside glycan receptors. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 413, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Guo, N.; Li, D.; Jin, M.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, G.; Pang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Duan, Z.J. Binding specificity of P[8] VP8* proteins of rotavirus vaccine strains with histo-blood group antigens. Virology 2016, 495, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Li, D.; Peng, R.; Guo, N.; Jin, M.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, G.; Pang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Qi, J.; et al. Functional and Structural Characterization of P[19] Rotavirus VP8* Interaction with Histo-blood Group Antigens. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 9758–9765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ramelot, T.A.; Huang, P.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Feizi, T.; Zhong, W.; Wu, F.T.; Tan, M.; Kennedy, M.A.; et al. Glycan Specificity of P[19] Rotavirus and Comparison with Those of Related P Genotypes. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 9983–9996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Ramani, S.; Czako, R.; Sankaran, B.; Yu, Y.; Smith, D.F.; Cummings, R.D.; Estes, M.K.; Venkataram Prasad, B.V. Structural basis of glycan specificity in neonate-specific bovine-human reassortant rotavirus. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; McGinnis, K.R.; Liu, Y.; Huang, P.; Tan, M.; Stuckert, M.R.; Burnside, R.E.; Jacob, E.G.; Ni, S.; Jiang, X.; et al. Structural basis of P[II] rotavirus evolution and host ranges under selection of histo-blood group antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2107963118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchs, A.; da Costa, A.C.; Cilli, A.; Komninakis, S.C.V.; Carmona, R.C.C.; Boen, L.; Morillo, S.G.; Sabino, E.C.; Timenetsky, M.D.C.S.T. Spread of the emerging equine-like G3P[8] DS-1-like genetic backbone rotavirus strain in Brazil and identification of potential genetic variants. J. Gen. Virol. 2019, 100, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer (p) or Probe (pb) ID 1, 2 | Nucleotide Sequence 5′-3′(Fluorophore/Quencher) | RVA Specificity/Gene 3 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSP3F (p) | ACCATCTWCACRTRACCCTCTATGAG | RVAWt 3/Rotarix/NSP3 | [32] |

| NSP3R (p) | GGTCACATAACGCCCCTATAGC | RVAWt 3/Rotarix/NSP3 | |

| NSP3RVA (pb) | AGTTAAAAGCTAACACTGTCAAA (VIC/BHQ) | RVAWt 3/Rotarix/NSP3 | |

| NSP2F (p) | GAACTTCCTTGAATATAAGATCACACTGA | Rotarix®/NSP2 | [30] |

| NSP2R (p) | TTGAAGACGTAAATGCATACCAATTC | Rotarix®/NSP2 | |

| NSP2Rotarix®(pb) | TCCAATAGATTGAAGT {C} AGTAA “C” GTTTCCA (FAM/BHQ) | Rotarix®/NSP2 | |

| VP4F (p) | TGTGAGTAA “C” GATTCAAATAAATGGAAGTT | Rotarix®/VP4 | |

| VP4R (p) | TCACCATGAAATGTCCATACTCTTCCACCA | Rotarix®/VP4 | |

| VP4F Rotarix®(pb) | ATA {C} CAGA {C} TTGTAGGAATA “Y” TTAAATA (FAM/BHQ) | Rotarix®/VP4 |

| Sample ID | Child Age | Rotarix® 1 Dose = (0), (1) or (2) | RVA Rotarix® Gene Detection | RVA VP4 (VP8*) Mutations (aa Change) | Clinical | HBGA 2 Sec+/Sec- (Lewis) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26282 3 | >6 months | 0 | VP4 | 144C > G (no change) | AGE | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) |

| 26673 | >1 month | 0 | VP4 | Control | Sec+ (Lea-Leb+) | |

| 26679 | <3 months | 1 | VP4 | AGE | Sec- ((Lea-Leb-) | |

| 26759 | >3 months | 1 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 27083 | >3 months | 1 | VP4 | Control | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 27089 | >6 months | 0 | NSP2 | AGE | Sec- (Lea-Leb-) | |

| 27105 | >1 month | 0 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea-Leb+) | |

| 27135 | <3 months | 0 | VP4 | Control | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 27173 | >6 months | 0 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 27227 | >3 months | 0 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 27253 | <3 months | 0 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea-Leb+) | |

| 27301 | <3 months | 2 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 27317 | >3 months | 0 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 27349 | <3 months | 0 | VP4/NSP2 | AGE | Sec- (Lea-Leb-) | |

| 27391 | >1 month | 2 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 27397 | <3 months | 0 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea-Leb+) | |

| 27627 | >3 months | 0 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 27711 | <3 months | 1 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea-Leb-) | |

| 27755 | >6 months | 2 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea-Leb+) | |

| 27813 | >6 months | 0 | VP4/NSP2 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea-Leb+) | |

| 28041 | >6 months | 0 | VP4/NSP2 | AGE | Sec- (Lea-Leb-) | |

| 28444 | >3 months | 1 | VP4/NSP2 | Control | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 28512 | >3 months | 2 | VP4 | Control | Sec+ (Lea-Leb+) | |

| 28514 | >6 months | 2 | VP4 | AGE | Sec- (Lea-Leb-) | |

| 28516 | <3 months | 1 | VP4 | Control | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 32456 | <3 months | 0 | VP4 | 499T > C (F167L) 787G > A (E263K) | AGE | Sec+ (Lea-Leb+) |

| 32520 | <3 months | 0 | VP4 | AGE | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) | |

| 32524 | <3 months | 0 | VP4 | AGE | Sec- (Lea-Leb-) | |

| 32526 | >6 months | 0 | VP4 | 499T > C (F167L) 644G > C (C215S) | Control | Sec+ (Lea+Leb+) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Silva, M.F.; Silva, B.V.d.; Ramalho, E.; Pimenta, Y.C.; Silva, L.L.P.d.; Vieira, L.d.S.; Xavier, M.d.P.T.P.; Olivares, A.I.O.; Leite, J.P.G.; Moraes, M.T.B.d. Examination of In Vivo Mutations in VP4 (VP8*) of the Rotarix® Vaccine from Shedding of Children Living in the Amazon Region. Viruses 2026, 18, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010070

Silva MF, Silva BVd, Ramalho E, Pimenta YC, Silva LLPd, Vieira LdS, Xavier MdPTP, Olivares AIO, Leite JPG, Moraes MTBd. Examination of In Vivo Mutations in VP4 (VP8*) of the Rotarix® Vaccine from Shedding of Children Living in the Amazon Region. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010070

Chicago/Turabian StyleSilva, Mauro França, Beatriz Vieira da Silva, Emanuelle Ramalho, Yan Cardoso Pimenta, Leonardo Luiz Pimenta da Silva, Laricy da Silva Vieira, Maria da Penha Trindade Pinheiro Xavier, Alberto Ignacio Olivares Olivares, José Paulo Gagliardi Leite, and Marcia Terezinha Baroni de Moraes. 2026. "Examination of In Vivo Mutations in VP4 (VP8*) of the Rotarix® Vaccine from Shedding of Children Living in the Amazon Region" Viruses 18, no. 1: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010070

APA StyleSilva, M. F., Silva, B. V. d., Ramalho, E., Pimenta, Y. C., Silva, L. L. P. d., Vieira, L. d. S., Xavier, M. d. P. T. P., Olivares, A. I. O., Leite, J. P. G., & Moraes, M. T. B. d. (2026). Examination of In Vivo Mutations in VP4 (VP8*) of the Rotarix® Vaccine from Shedding of Children Living in the Amazon Region. Viruses, 18(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010070