Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Seroprevalence in a Cohort of German Forestry Workers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LCMV | lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus |

| HMHZ | house mouse hybrid zone |

| IFA | immunofluorescence assay |

| IgG | immunoglobulin G |

| PBS | phosphate-buffered saline |

| CCF | chest cavity fluid |

References

- Ackermann, R.; Stille, W.; Blumenthal, W.; Helm, E.B.; Keller, K.; Baldus, O. Syrische Goldhamster als Überträger von Lymphozytärer Choriomeningitis. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1972, 45, 1725–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, H.H.; Knight, E.H. Natural routes for post-natal transmission of murine lymphocytic choriomeningitis. Lab. Anim. 1973, 7, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, J.E.; Klein, S.L.; Glass, G.E. A Case Study of Two Rodent-Borne Viruses: Not Always the Same Old Suspects. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, L.L.; Peters, C.J.; Ksiazek, T.G. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus: An Unrecognized Teratogenic Pathogen. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 1995, 1, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, L.L.; Mets, M. Congenital Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Infection: Decade of Rediscovery. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.R.; Bharucha, T.; Breuer, J. Encephalitis diagnosis using metagenomics: Application of next generation sequencing for undiagnosed cases. J. Infect. 2018, 76, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schibler, M.; Eperon, G.; Kenfak, A.; Lascano, A.; Vargas, M.I.; Stahl, J.P. Diagnostic tools to tackle infectious causes of encephalitis and meningoencephalitis in immunocompetent adults in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macneil, A.; Ströher, U.; Farnon, E.; Campbell, S.; Cannon, D.; Paddock, C.D.; Drew, C.P.; Kuehnert, M.; Knust, B.; Gruenenfelder, R.; et al. Solid organ transplant-associated lymphocytic choriomeningitis, United States, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 1256–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyal, J.; Gandhi, S.; Cossaboom, C.M.; Leach, A.; Patel, K.; Golden, M.; Canterino, J.; Landry, M.-L.; Cannon, D.; Choi, M.; et al. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus in Person Living with HIV, Connecticut, USA, 2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 1886–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonthius, D.J. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: A prenatal and postnatal threat. Adv. Pediatr. 2009, 56, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, R.; Körver, G.; Turss, R.; Wönne, R.; Hochgesand, P. Pränatale Infektion mit dem Virus der Lymphozytären Choriomeningitis. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1974, 99, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonthius, D.J. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus injures the developing brain: Effects and mechanisms. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 95, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehl, C.; Oestereich, L.; Groseth, A.; Ulrich, R.G. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in Germany—A neglected zoonotic pathogen. Berl. Münch. tierärztl. Wochenschr. 2024, 137, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann, R.; Bloedhorn, H.; Kupper, B.; Winkens, I.; Scheid, W. Über die Verbreitung des Virus der lymphocytären Choriomeningitis unter den Mäusen in Westdeutschland. Zentralbl. Bakt. Parasitol. Infekt. Hyg. 1964, 194, 407–430. [Google Scholar]

- Asper, M.; Hofmann, P.; Osmann, C.; Funk, J.; Metzger, C.; Bruns, M.; Kaup, F.J.; Schmitz, H.; Günther, S. First outbreak of callitrichid hepatitis in Germany: Genetic characterization of the causative lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus strains. Virology 2001, 284, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, R. Gefährdung des Menschen durch LCM-Virusverseuchte Goldhamster. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 1977, 102, 1367–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, W.; Kessler, R.; Ackermann, R. Über die Durchseuchung der ländlichen Bevölkerung in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland mit dem Virus der lymphozytären Choriomeningitis. Zentralbl Bakteriol Orig. 1970, 2013, 36–48. [Google Scholar]

- Mehl, C.; Wylezich, C.; Geiger, C.; Schauerte, N.; Mätz-Rensing, K.; Nesseler, A.; Höper, D.; Linnenbrink, M.; Beer, M.; Heckel, G.; et al. Reemergence of Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Mammarenavirus, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehl, C.; Adeyemi, O.A.; Wylezich, C.; Höper, D.; Beer, M.; Triebenbacher, C.; Heckel, G.; Ulrich, R.G. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Lineage V in Wood Mice, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornůsková, A.; Hiadlovská, Z.; Macholán, M.; Piálek, J.; Bellocq, J.G.d. New Perspective on the Geographic Distribution and Evolution of Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus, Central Europe. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 2638–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertens, M.; Hofmann, J.; Petraityte-Burneikiene, R.; Ziller, M.; Sasnauskas, K.; Friedrich, R.; Niederstrasser, O.; Krüger, D.H.; Groschup, M.H.; Petri, E.; et al. Seroprevalence study in forestry workers of a non-endemic region in eastern Germany reveals infections by Tula and Dobrava-Belgrade hantaviruses. Med. Microbiol. Immun. 2011, 200, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wölfel, S.; Speck, S.; Essbauer, S.; Thoma, B.R.; Mertens, M.; Werdermann, S.; Niederstrasser, O.; Petri, E.; Ulrich, R.G.; Wölfel, R.; et al. High seroprevalence for indigenous spotted fever group rickettsiae in forestry workers from the federal state of Brandenburg, Eastern Germany. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2017, 8, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dremsek, P.; Wenzel, J.J.; Johne, R.; Ziller, M.; Hofmann, J.; Groschup, M.H.; Werdermann, S.; Mohn, U.; Dorn, S.; Motz, M.; et al. Seroprevalence study in forestry workers from eastern Germany using novel genotype 3- and rat hepatitis E virus-specific immunoglobulin G ELISAs. Med. Microbiol. Immun. 2012, 201, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimov, P.; Zerweck, J.; Maksimov, A.; Hotop, A.; Gross, U.; Pleyer, U.; Spekker, K.; Däubener, W.; Werdermann, S.; Niederstrasser, O.; et al. Peptide microarray analysis of in silico-predicted epitopes for serological diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii infection in humans. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2012, 19, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimov, P.; Zerweck, J.; Maksimov, A.; Hotop, A.; Gross, U.; Spekker, K.; Däubener, W.; Werdermann, S.; Niederstrasser, O.; Petri, E.; et al. Analysis of clonal type-specific antibody reactions in Toxoplasma gondii seropositive humans from Germany by peptide-microarray. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.I.; Hughes, J.J.; Herman, J.S.; Baines, J.F.; Giménez, M.D.; Gray, M.M.; Hardouin, E.A.; Payseur, B.A.; Ryan, P.G.; Sánchez-Chardi, A.; et al. House Mice in the Atlantic Region: Genetic Signals of Their Human Transport. Genes 2024, 15, 1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harr, B.; Karakoc, E.; Neme, R.; Teschke, M.; Pfeifle, C.; Pezer, Ž.; Babiker, H.; Linnenbrink, M.; Montero, I.; Scavetta, R.; et al. Genomic resources for wild populations of the house mouse, Mus musculus and its close relative Mus spretus. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, C.; Schlegel, M.; Linnenbrink, M.; Hutterer, R.; König, P.; Ehlers, B.; Fischer, K.; Ryll, R.; Lewitzki, J.; Sauer, S.; et al. Indigenous house mice dominate small mammal communities in northern Afghan military bases. BMC Zool. 2017, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelz, H.-J.; Rost, S.; Müller, E.; Esther, A.; Ulrich, R.G.; Müller, C.R. Distribution and frequency of VKORC1 sequence variants conferring resistance to anticoagulants in Mus musculus. Pest. Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceianu, C.; Tatulescu, D.; Muntean, M.; Molnar, G.B.; Emmerich, P.; Günther, S.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis in a pet store worker in Romania. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2008, 15, 1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software; Posit Team: Boston, MA, USA, 2025.

- Camp, J.V.; Nowotny, N.; Aberle, S.W.; Redlberger-Fritz, M. Retrospective Screening for Zoonotic Viruses in Encephalitis Cases in Austria, 2019–2023, Reveals Infection with Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus but Not with Rustrela Virus or Tahyna Virus. Viruses 2025, 17, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Essbauer, S.S.; Mayer-Scholl, A.; Poppert, S.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Klempa, B.; Henning, K.; Schares, G.; Groschup, M.H.; Spitzenberger, F.; et al. Multiple infections of rodents with zoonotic pathogens in Austria. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2014, 14, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balard, A.; Heitlinger, E. Shifting focus from resistance to disease tolerance: A review on hybrid house mice. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 12, e8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balard, A.; Jarquín-Díaz, V.H.; Jost, J.; Mittné, V.; Böhning, F.; Ďureje, Ľ.; Piálek, J.; Heitlinger, E. Coupling between tolerance and resistance for two related Eimeria parasite species. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 13938–13948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasimuddin; Bryja, J.; Ribas, A.; Baird, S.J.E.; Piálek, J.; Goüy de Bellocq, J. Testing parasite ‘intimacy’: The whipworm Trichuris muris in the European house mouse hybrid zone. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 2688–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balard, A.; Jarquín-Díaz, V.H.; Jost, J.; Martincová, I.; Ďureje, Ľ.; Piálek, J.; Macholán, M.; Goüy de Bellocq, J.; Baird, S.J.E.; Heitlinger, E. Intensity of infection with intracellular Eimeria spp. and pinworms is reduced in hybrid mice compared to parental subspecies. J. Evol. Biol. 2020, 33, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxenhofer, M.; Schmidt, S.; Ulrich, R.G.; Heckel, G. Secondary contact between diverged host lineages entails ecological speciation in a European hantavirus. PLoS Biol. 2019, 17, e3000142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehl, C.; Adeyemi, O.A.; Möhrer, F.J.; Wylezich, C.; Sander, S.; Schmidt, K.; Geiger, C.; Schauerte, N.; Wurr, S.; Mätz-Rensing, K.; et al. Persistence, spill over, and evolution of co-occurring lineages of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Virus Evol. 2025, 11, veaf085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.; Santos, T.; Tellería, J. Effects of forest fragmentation on the winter body condition and population parameters of an habitat generalist, the wood mouse Apodemus sylvaticus: A test of hypotheses. Acta Oecologica 1999, 20, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janova, E.; Heroldova, M. Response of small mammals to variable agricultural landscapes in Central Europe. Mamm. Biol. 2016, 81, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.; Montgomery, W.I. Intrapopulation variation in the diet of the wood mouse Apodemus sylvaticus. J. Zool. Lond. 1990, 222, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöller, L.; Faulde, M.; Meisel, H.; Ruh, B.; Kimmig, P.; Schelling, U.; Zeier, M.; Kulzer, P.; Becker, C.; Roggendorf, M.; et al. Seroprevalence of hantavirus antibodies in Germany as determined by a new recombinant enzyme immunoassay. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995, 14, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, W.; Bocklisch, H.; Schüler, G.; Hotzel, H.; Neubauer, H.; Otto, P. Detection of Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica in a European brown hare (Lepus europaeus) in Thuringia, Germany. Vet. Microbiol. 2007, 123, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, P.; Kohlmann, R.; Müller, W.; Julich, S.; Geis, G.; Gatermann, S.G.; Peters, M.; Wolf, P.J.; Karlsson, E.; Forsman, M.; et al. Hare-to-human transmission of Francisella tularensis subsp. holarctica, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurke, A.; Bannert, N.; Brehm, K.; Fingerle, V.; Kempf, V.A.J.; Kömpf, D.; Lunemann, M.; Mayer-Scholl, A.; Niedrig, M.; Nöckler, K.; et al. Serological survey of Bartonella spp., Borrelia burgdorferi, Brucella spp., Coxiella burnetii, Francisella tularensis, Leptospira spp., Echinococcus, Hanta-, TBE- and XMR-virus infection in employees of two forestry enterprises in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, 2011–2013. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015, 305, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schielke, A.; Ibrahim, V.; Czogiel, I.; Faber, M.; Schrader, C.; Dremsek, P.; Ulrich, R.G.; Johne, R. Hepatitis E virus antibody prevalence in hunters from a district in Central Germany, 2013: A cross-sectional study providing evidence for the benefit of protective gloves during disembowelling of wild boars. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczek, A.; Rudek, A.; Bartosik, K.; Szymanska, J.; Wójcik-Fatla, A. Seroepidemiological study of Lyme borreliosis among forestry workers in southern Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2009, 16, 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Tokarska-Rodak, M.; Plewik, D.; Michalski, A.J.; Kołodziej, M.; Mełgieś, A.; Pańczuk, A.; Konon, H.; Niemcewicz, M. Serological surveillance of vector-borne and zoonotic diseases among hunters in eastern Poland. J. Vector Dis. 2016, 53, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żukiewicz-Sobczak, W.; Zwoliński, J.; Chmielewska-Badora, J.; Galińska, E.M.; Cholewa, G.; Krasowska, E.; Zagórski, J.; Wojtyła, A.; Tomasiewicz, K.; Kłapeć, T. Prevalence of antibodies against selected zoonotic agents in forestry workers from eastern and southern Poland. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2014, 21, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgroi, G.; Iatta, R.; Lia, R.P.; Napoli, E.; Buono, F.; Bezerra-Santos, M.A.; Veneziano, V.; Otranto, D. Tick exposure and risk of tick-borne pathogens infection in hunters and hunting dogs: A citizen science approach. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e386–e393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsiadły, E.; Chmielewski, T.; Karbowiak, G.; Kędra, E.; Tylewska-Wierzbanowska, S. The occurrence of spotted fever rickettsioses and other tick-borne infections in forest workers in Poland. Vector-Borne Zoonot 2011, 11, 985–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Liu, S.; Song, J.; Han, L.; Zhang, H.; Wu, C.; Wang, C.; Zhou, H.; Wang, J. Seroprevalence of Wenzhou virus in China. Biosaf. Health 2020, 2, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saijo, M.; Georges-Courbot, M.-C.; Marianneau, P.; Romanowski, V.; Fukushi, S.; Mizutani, T.; Georges, A.-J.; Kurata, T.; Kurane, I.; Morikawa, S. Development of recombinant nucleoprotein-based diagnostic systems for Lassa fever. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2007, 14, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

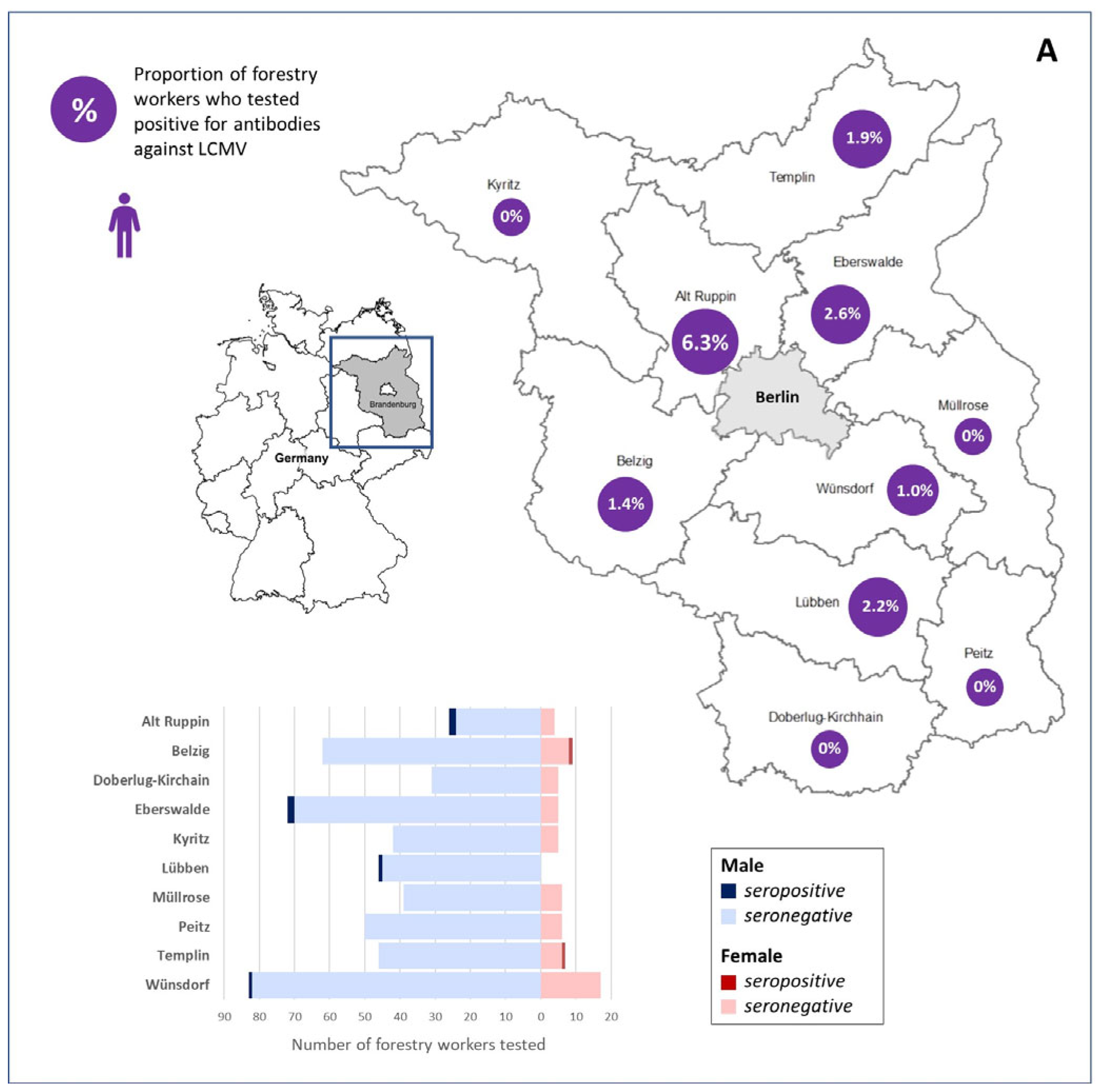

| Forestry Office | Total Number | Sex | Number (%) | Average Age ± Standard Deviation (Years) | Number Anti-LCMV-IgG Positive (%) and 95% CI | Number Anti-LCMV-IgG Positive Total (%) and 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alt Ruppin | 32 | Male | 28 (87.5) | 48.54 ± 6.68 | 2 (7.1) 0.9–23.5 | 2 (6.3) 0.8–20.8 |

| Female | 4 (12.5) | 47.25 ± 9.03 | 0 (0) 0.0–60.2 | |||

| Doberlug-Kirchhain | 36 | Male | 31 (86.1) | 52.29 ± 4.87 | 0 (0) 0.0–11.2 | 0 (0) 0.0–9.7 |

| Female | 5 (13.9) | 48.20 ± 5.63 | 0 (0) 0.0–52.2 | |||

| Belzig | 71 | Male | 62 (87.3) | 49.23 ± 8.30 | 0 (0) 0.0–5.8 | 1 (1.4) 0.0–7.6 |

| Female | 9 (12.7) | 51.00 ± 3.97 | 1 (11.1) 0.3–48.2 | |||

| Wünsdorf | 101 | Male | 83 (82.2) | 20 ± 7.49 | 1 (1.2) 0.0–6.5 | 1 (1.0) 0.0–5.4 |

| Female | 19 (17.8) | 46.17 ± 6.54 | 0 (0) 0.0–18.5 | |||

| Lübben | 46 | Male | 46 (100.0) | 49.37 ± 6.48 | 1 (2.2) 0.1–11.5 | 1 (2.2) 0.1–11.5 |

| Female | 0 (0.0) | NA * | 0 (0) NA * | |||

| Kyritz | 47 | Male | 42 (89.4) | 49.05 ± 6.68 | 0 (0) 0.0–8.4 | 0 (0) 0.0–7.5 |

| Female | 5 (10.6) | 49.60 ± 6.39 | 0 (0) 0.0–52.2 | |||

| Peitz | 56 | Male | 50 (89.3) | 48.68 ± 7.90 | 0 (0) 0.0–7.1 | 0 (0) 0.0–6.4 |

| Female | 6 (10.7) | 42.67 ± 6.31 | 0 (0) 0.0–45.9 | |||

| Eberswalde | 77 | Male | 72 (93.5) | 45.93 ± 7.35 | 2 (2.8) 0.3–9.7 | 2 (2.6) 0.3–9.1 |

| Female | 5 (6.5) | 51.40 ± 3.36 | 0 (0) 0.0–52.2 | |||

| Templin | 52 | Male | 46 (88.5) | 44.00 ± 8.35 | 0 (0) 0.0–7.7 | 1 (1.9) 0.0–10.3 |

| Female | 6 (11.5) | 45.67 ± 11.43 | 1 (16.7) 0.0–64.1 | |||

| Müllrose | 45 | Male | 39 (86.7) | 47.18 ± 8.13 | 0 (0) 0.0–9.0 | 0 (0) 0.0–7.9 |

| Female | 6 (13.3) | 54.50 ± 3.39 | 0 (0) 0.0–45.9 | |||

| Total | 563 | Male | 499 (88.6) | 48.03 ± 7.62 | 6 (1.2) 0.4–2.6 | 8 (1.4) 0.6–2.8 |

| Female | 64 (11.4) | 48.08 ± 6.92 | 2 (3.1) 0.4–10.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mehl, C.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J.; Becker-Ziaja, B.; Werdermann, S.; Niederstraßer, O.; Böhmer, M.M.; Ulrich, R.G. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Seroprevalence in a Cohort of German Forestry Workers. Viruses 2026, 18, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010004

Mehl C, Schmidt-Chanasit J, Becker-Ziaja B, Werdermann S, Niederstraßer O, Böhmer MM, Ulrich RG. Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Seroprevalence in a Cohort of German Forestry Workers. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleMehl, Calvin, Jonas Schmidt-Chanasit, Beate Becker-Ziaja, Sandra Werdermann, Olaf Niederstraßer, Merle M. Böhmer, and Rainer G. Ulrich. 2026. "Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Seroprevalence in a Cohort of German Forestry Workers" Viruses 18, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010004

APA StyleMehl, C., Schmidt-Chanasit, J., Becker-Ziaja, B., Werdermann, S., Niederstraßer, O., Böhmer, M. M., & Ulrich, R. G. (2026). Lymphocytic Choriomeningitis Virus Seroprevalence in a Cohort of German Forestry Workers. Viruses, 18(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010004