HIV-1 Nef Uses a Conserved Pocket to Recruit the N-Terminal Cytoplasmic Tail of Serinc3

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Accession ID

2.2. Fusion Construct Design and Protein Expression and Purification

2.3. Binary Binding Test Using Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC)

2.4. Competition of TMR-Cyclic-CD4CD by Unlabeled MBP-NTT/ICL in the FP Assay

2.5. Labeling NTT with the TMR Fluorophore

2.6. Fluorescence Polarization Assay Using α-Nef/σ2 and TMR-NTT

2.7. Plasmids and Mammalian Cells

2.8. Serinc3 Virion Incorporation and Immunoblotting

3. Results

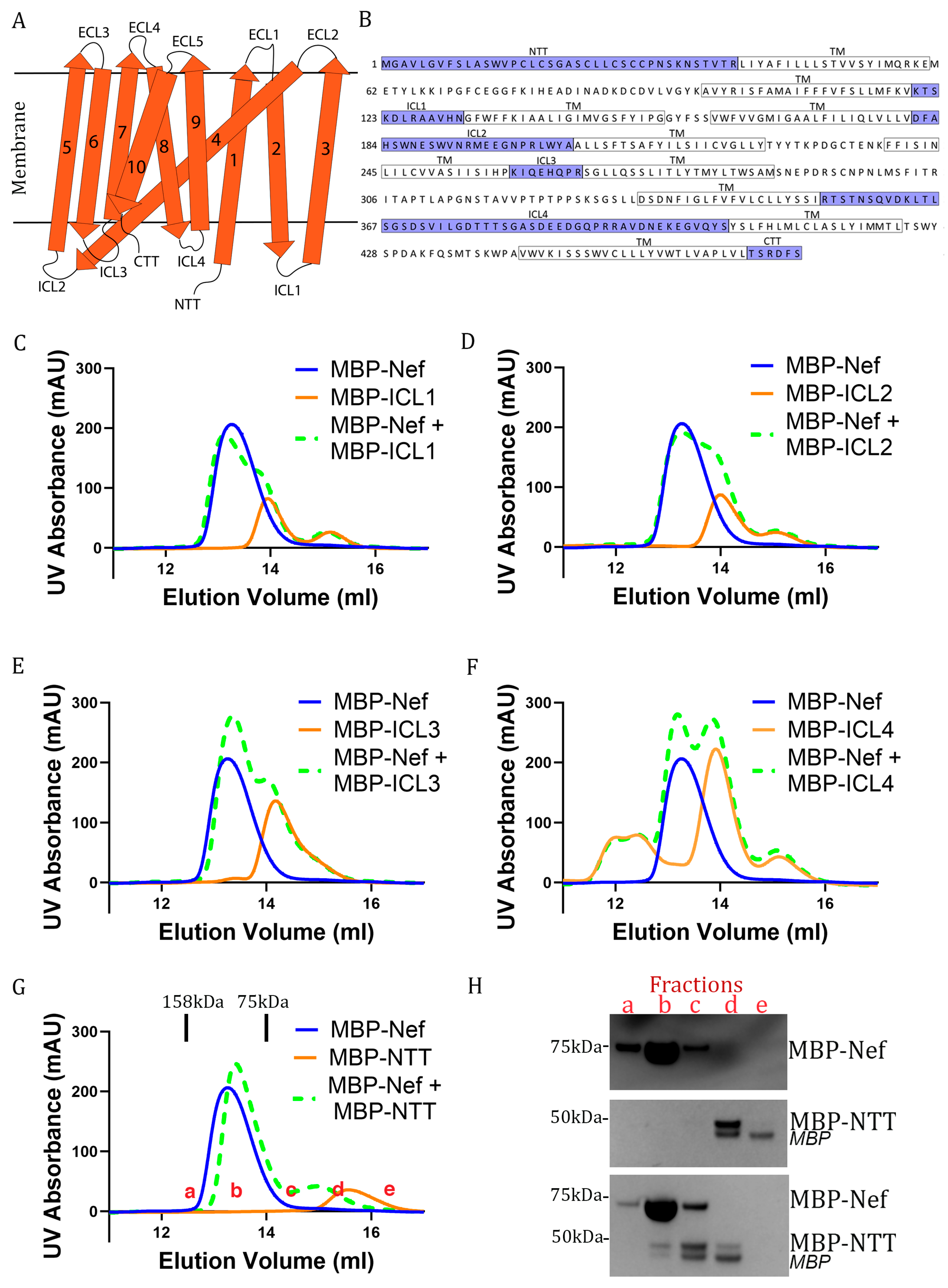

3.1. Nef Binds to the N-Terminal Cytoplasmic Tail of Serinc3 in Vitro

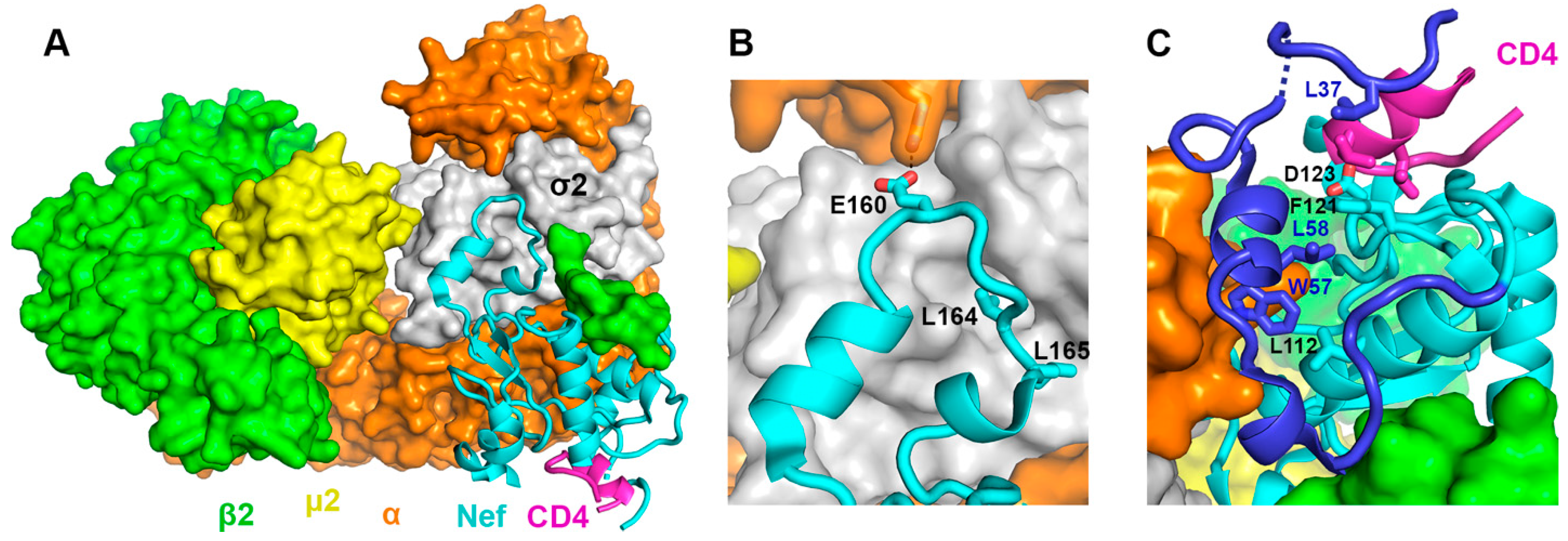

3.2. Serinc3 NTT-Binding and CD4CD-Binding Involve the Same Conserved Pocket on Nef

3.3. CD4CD- and Serinc3 NTT-Binding Share the Same Determinants in Nef and Should Involve the Same Conformation of Nef

3.4. Virion Exclusion of Serinc3 Requires the Same Nef Residues Important for CD4 Downregulation

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Inuzuka, M.; Hayakawa, M.; Ingi, T. Serinc, an activity-regulated protein family, incorporates serine into membrane lipid synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 35776–35783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Ortiz, L.; Luedde, T.; Munk, C. HIV-1 restriction by SERINC5. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2023, 212, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, A.; Chande, A.; Ziglio, S.; De Sanctis, V.; Bertorelli, R.; Goh, S.L.; McCauley, S.M.; Nowosielska, A.; Antonarakis, S.E.; Luban, J.; et al. HIV-1 Nef promotes infection by excluding SERINC5 from virion incorporation. Nature 2015, 526, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usami, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gottlinger, H.G. SERINC3 and SERINC5 restrict HIV-1 infectivity and are counteracted by Nef. Nature 2015, 526, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood, C.; Marin, M.; Chande, A.; Pizzato, M.; Melikyan, G.B. SERINC5 protein inhibits HIV-1 fusion pore formation by promoting functional inactivation of envelope glycoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 6014–6026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.E.; Kiessling, V.; Pornillos, O.; White, J.M.; Ganser-Pornillos, B.K.; Tamm, L.K. HIV-cell membrane fusion intermediates are restricted by Serincs as revealed by cryo-electron and TIRF microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15183–15195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shi, J.; Qiu, X.; Chai, Q.; Frabutt, D.A.; Schwartz, R.C.; Zheng, Y.H. CD4 Expression and Env Conformation Are Critical for HIV-1 Restriction by SERINC5. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00544-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beitari, S.; Ding, S.; Pan, Q.; Finzi, A.; Liang, C. Effect of HIV-1 Env on SERINC5 Antagonism. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, R.P.; Yan, J.; Heeney, J.; McClure, M.O.; Gottlinger, H.; Luban, J.; Pizzato, M. Nef decreases HIV-1 sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies that target the membrane-proximal external region of TMgp41. PLoS Pathogen. 2011, 7, e1002442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, A.; Aiken, C. SERINC5 Inhibits HIV-1 Infectivity by Altering the Conformation of gp120 on HIV-1 Particles. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e00594-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautz, B.; Wiedemann, H.; Luchtenborg, C.; Pierini, V.; Kranich, J.; Glass, B.; Krausslich, H.G.; Brocker, T.; Pizzato, M.; Ruggieri, A.; et al. The host-cell restriction factor SERINC5 restricts HIV-1 infectivity without altering the lipid composition and organization of viral particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 13702–13713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonhardt, S.A.; Purdy, M.D.; Grover, J.R.; Yang, Z.; Poulos, S.; McIntire, W.E.; Tatham, E.A.; Erramilli, S.K.; Nosol, K.; Lai, K.K.; et al. Antiviral HIV-1 SERINC restriction factors disrupt virus membrane asymmetry. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhel, N.J.; Kirchhoff, F. Implications of Nef: Host cell interactions in viral persistence and progression to AIDS. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009, 339, 147–175. [Google Scholar]

- Trible, R.P.; Emert-Sedlak, L.; Smithgall, T.E. HIV-1 Nef selectively activates Src family kinases Hck, Lyn, and c-Src through direct SH3 domain interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 27029–27038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarafdar, S.; Poe, J.A.; Smithgall, T.E. The Accessory Factor Nef Links HIV-1 to Tec/Btk Kinases in an Src Homology 3 Domain-dependent Manner. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 15718–15728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, E.A.; daSilva, L.L. HIV-1 Nef: Taking Control of Protein Trafficking. Traffic 2016, 17, 976–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lama, J.; Mangasarian, A.; Trono, D. Cell-surface expression of CD4 reduces HIV-1 infectivity by blocking Env incorporation in a Nef- and Vpu-inhibitable manner. Curr. Biol. 1999, 9, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.N.; Lukhele, S.; Hajjar, F.; Routy, J.P.; Cohen, E.A. HIV Nef and Vpu protect HIV-infected CD4+ T cells from antibody-mediated cell lysis through down-modulation of CD4 and BST2. Retrovirology 2014, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veillette, M.; Desormeaux, A.; Medjahed, H.; Gharsallah, N.E.; Coutu, M.; Baalwa, J.; Guan, Y.; Lewis, G.; Ferrari, G.; Hahn, B.H.; et al. Interaction with cellular CD4 exposes HIV-1 envelope epitopes targeted by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 2633–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Gasser, R.; Gendron-Lepage, G.; Medjahed, H.; Tolbert, W.D.; Sodroski, J.; Pazgier, M.; Finzi, A. CD4 Incorporation into HIV-1 Viral Particles Exposes Envelope Epitopes Recognized by CD4-Induced Antibodies. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01403-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, K.L.; Chen, B.K.; Kalams, S.A.; Walker, B.D.; Baltimore, D. HIV-1 Nef protein protects infected primary cells against killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature 1998, 391, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, M.E.; Bronson, S.; Lock, M.; Neumann, M.; Pavlakis, G.N.; Skowronski, J. Co-localization of HIV-1 Nef with the AP-2 adaptor protein complex correlates with Nef-induced CD4 down-regulation. Embo J. 1997, 16, 6964–6976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, R.; Lindwasser, O.W.; Smith, W.J.; Hurley, J.H.; Bonifacino, J.S. Downregulation of CD4 by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef is dependent on clathrin and involves direct interaction of Nef with the AP2 clathrin adaptor. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 3877–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roeth, J.F.; Williams, M.; Kasper, M.R.; Filzen, T.M.; Collins, K.L. HIV-1 Nef disrupts MHC-1 trafficking by recruiting AP-1 to the MHC-1 cytoplasmic tail. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 167, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noviello, C.M.; Benichou, S.; Guatelli, J.C. Cooperative binding of the class I major histocompatibility complex cytoplasmic domain and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef to the endosomal AP-1 complex via its mu subunit. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 1249–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonderlich, E.R.; Williams, M.; Collins, K.L. The tyrosine binding pocket in the adaptor protein 1 (AP-1) mu 1 subunit is necessary for nef to recruit AP-1 to the major histocompatibility complex class I cytoplasmic tail. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 3011–3022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Lau, D.; Noviello, C.M.; Ghosh, P.; Guatelli, J.C. An MHC-I Cytoplasmic Domain/HIV-1 Nef Fusion Protein Binds Directly to the mu Subunit of the AP-1 Endosomal Coat Complex. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H.M.; Pandori, M.W.; Guatelli, J.C. Interaction of HIV-1 Nef with the cellular dileucine-based sorting pathway is required for CD4 down-regulation and optimal viral infectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 11229–11234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzato, M.; Helander, A.; Popova, E.; Calistri, A.; Zamborlini, A.; Palu, G.; Gottlinger, H.G. Dynamin 2 is required for the enhancement of HIV-1 infectivity by Nef. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 6812–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traub, L.M.; Bonifacino, J.S. Cargo recognition in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a016790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.F.; Park, S.Y.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Hurley, J.H. How HIV-1 Nef hijacks the AP-2 clathrin adaptor to downregulate CD4. eLife 2014, 3, e01754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Kaake, R.M.; Echeverria, I.; Suarez, M.; Karimian Shamsabadi, M.; Stoneham, C.; Ramirez, P.W.; Kress, J.; Singh, R.; Sali, A.; et al. Structural basis of CD4 downregulation by HIV-1 Nef. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Blair, W.; Truant, R.; Cullen, B.R. Identification of regions in HIV-1 Nef required for efficient downregulation of cell surface CD4. Virology 1997, 231, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.X.; Heveker, N.; Fackler, O.T.; Arold, S.; Le Gall, S.; Janvier, K.; Peterlin, B.M.; Dumas, C.; Schwartz, O.; Benichou, S.; et al. Mutation of a conserved residue (D123) required for oligomerization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef protein abolishes interaction with human thioesterase and results in impairment of Nef biological functions. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 5310–5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poe, J.A.; Smithgall, T.E. HIV-1 Nef dimerization is required for Nef-mediated receptor downregulation and viral replication. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 394, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangasarian, A.; Piguet, V.; Wang, J.K.; Chen, Y.L.; Trono, D. Nef-induced CD4 and major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) down-regulation are governed by distinct determinants: N-terminal alpha helix and proline repeat of Nef selectively regulate MHC-I trafficking. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 1964–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, W.; Usami, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gottlinger, H. A Long Cytoplasmic Loop Governs the Sensitivity of the Anti-viral Host Protein SERINC5 to HIV-1 Nef. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudt, R.P.; Smithgall, T.E. Nef homodimers down-regulate SERINC5 by AP-2-mediated endocytosis to promote HIV-1 infectivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15540–15552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Xiong, R.; Zhou, T.; Su, P.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, X.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Yu, C.; Wang, B.; et al. HIV-1 Nef Antagonizes SERINC5 Restriction by Downregulation of SERINC5 via the Endosome/Lysosome System. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e00196-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananth, S.; Morath, K.; Trautz, B.; Tibroni, N.; Shytaj, I.L.; Obermaier, B.; Stolp, B.; Lusic, M.; Fackler, O.T. Multifunctional Roles of the N-Terminal Region of HIV-1SF2Nef Are Mediated by Three Independent Protein Interaction Sites. J. Virol. 2019, 94, e01398-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Firrito, C.; Bertelli, C.; Rosa, A.; Chande, A.; Ananth, S.; van Dijk, H.; Fackler, O.T.; Stoneham, C.; Singh, R.; Guatelli, J.; et al. A Conserved Acidic Residue in the C-Terminal Flexible Loop of HIV-1 Nef Contributes to the Activity of SERINC5 and CD4 Downregulation. Viruses 2023, 15, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, M.A.; Warmerdam, M.T.; Atchison, R.E.; Miller, M.D.; Greene, W.C. Dissociation of the Cd4 down-Regulation and Viral Infectivity Enhancement Functions of Human-Immunodeficiency-Virus Type-1 Nef. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 4112–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mumby, M.J.; Johnson, A.L.; Trothen, S.M.; Edgar, C.R.; Gibson, R.; Stathopulos, P.B.; Arts, E.J.; Dikeakos, J.D. An Amino Acid Polymorphism within the HIV-1 Nef Dileucine Motif Functionally Uncouples Cell Surface CD4 and SERINC5 Downregulation. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0058821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermaier, B.; Ananth, S.; Tibroni, N.; Pierini, V.; Shytaj, I.L.; Diaz, R.S.; Lusic, M.; Fackler, O.T. Patient-Derived HIV-1 Nef Alleles Reveal Uncoupling of CD4 Downregulation and SERINC5 Antagonism Functions of the Viral Pathogenesis Factor. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2020, 85, e23–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janaka, S.K.; Palumbo, A.V.; Tavakoli-Tameh, A.; Evans, D.T. Selective Disruption of SERINC5 Antagonism by Nef Impairs SIV Replication in Primary CD4+ T Cells. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e01911-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimian Shamsabadi, M.; Jia, X. A fluorescence polarization assay for high-throughput screening of inhibitors against HIV-1 Nef-mediated CD4 downregulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Ho, S.O.; Gassman, N.R.; Korlann, Y.; Landorf, E.V.; Collart, F.R.; Weiss, S. Efficient site-specific labeling of proteins via cysteines. Bioconjug. Chem. 2008, 19, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Stoneham, C.; Lim, C.; Jia, X.; Guenaga, J.; Wyatt, R.; Wertheim, J.O.; Xiong, Y.; Guatelli, J. Phosphoserine acidic cluster motifs bind distinct basic regions on the mu subunits of clathrin adaptor protein complexes. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 15678–15690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, A.; Gendelman, H.E.; Koenig, S.; Folks, T.; Willey, R.; Rabson, A.; Martin, M.A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J. Virol. 1986, 59, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowers, M.Y.; Spina, C.A.; Kwoh, T.J.; Fitch, N.J.S.; Richman, D.D.; Guatelli, J.C. Optimal Infectivity in-Vitro of Human-Immunodeficiency-Virus Type-1 Requires an Intact Nef Gene. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 2906–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spina, C.A.; Kwoh, T.J.; Chowers, M.Y.; Guatelli, J.C.; Richman, D.D. The Importance of Nef in the Induction of Human-Immunodeficiency-Virus Type-1 Replication from Primary Quiescent Cd4 Lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1994, 179, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, X.F.; Singh, R.; Homann, S.; Yang, H.T.; Guatelli, J.; Xiong, Y. Structural basis of evasion of cellular adaptive immunity by HIV-1 Nef. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 701–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffalo, C.Z.; Sturzel, C.M.; Heusinger, E.; Kmiec, D.; Kirchhoff, F.; Hurley, J.H.; Ren, X. Structural Basis for Tetherin Antagonism as a Barrier to Zoonotic Lentiviral Transmission. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 359–368.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.E.; Lim, A.; Woody, M.; Taklifi, P.; Yeasmin, F.; Wang, K.; Lewinski, M.K.; Singh, R.; Stoneham, C.A.; Jia, X.; et al. Adaptor Protein Complexes in HIV-1 Pathogenesis: Mechanisms and Therapeutic Potential. Viruses 2025, 17, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.; Roeth, J.F.; Kasper, M.R.; Filzen, T.M.; Collins, K.L. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef domains required for disruption of major histocompatibility complex class I trafficking are also necessary for coprecipitation of Nef with HLA-A2. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, E.; Kuo, L.S.; Krisko, J.F.; Tomchick, D.R.; Garcia, J.V.; Foster, J.L. Dynamic evolution of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pathogenic factor, Nef. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyoda, M.; Kamori, D.; Tan, T.S.; Goebuchi, K.; Ohashi, J.; Carlson, J.; Kawana-Tachikawa, A.; Gatanaga, H.; Oka, S.; Pizzato, M.; et al. Impaired ability of Nef to counteract SERINC5 is associated with reduced plasma viremia in HIV-infected individuals. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olety, B.; Usami, Y.; Wu, Y.; Peters, P.; Gottlinger, H. AP-2 Adaptor Complex-Dependent Enhancement of HIV-1 Replication by Nef in the Absence of the Nef/AP-2 Targets SERINC5 and CD4. mBio 2023, 14, e0338222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, S.; Schievink, S.I.; Schulte, A.; Blankenfeldt, W.; Fackler, O.T.; Geyer, M. Molecular design, functional characterization and structural basis of a protein inhibitor against the HIV-1 pathogenicity factor Nef. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado, J.J.; Tarafdar, S.; Yeh, J.I.; Smithgall, T.E. Interaction with the Src homology (SH3-SH2) region of the Src-family kinase Hck structures the HIV-1 Nef dimer for kinase activation and effector recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 28539–28553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhuri, R.; Mattera, R.; Lindwasser, O.W.; Robinson, M.S.; Bonifacino, J.S. A Basic Patch on alpha-Adaptin Is Required for Binding of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Nef and Cooperative Assembly of a CD4-Nef-AP-2 Complex. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 2518–2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, V.E.; Rosa, A.; Bertelli, C.; Struwe, W.B.; Maslen, S.L.; Corey, R.; Liko, I.; Hassall, M.; Mattiuzzo, G.; Ballandras-Colas, A.; et al. A bipartite structural organization defines the SERINC family of HIV-1 restriction factors. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Jaular, L.; Nevo, N.; Schessner, J.P.; Tkach, M.; Jouve, M.; Dingli, F.; Loew, D.; Witwer, K.W.; Ostrowski, M.; Borner, G.H.H.; et al. Unbiased proteomic profiling of host cell extracellular vesicle composition and dynamics upon HIV-1 infection. Embo J. 2021, 40, e105492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva-Januario, M.E.; da Costa, C.S.; Tavares, L.A.; Oliveira, A.K.; Januario, Y.C.; de Carvalho, A.N.; Cassiano, M.H.A.; Rodrigues, R.L.; Miller, M.E.; Palameta, S.; et al. HIV-1 Nef Changes the Proteome of T Cells Extracellular Vesicles Depleting IFITMs and Other Antiviral Factors. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2023, 22, 100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.W.; Mwimanzi, F.M.; Mann, J.K.; Bwana, M.B.; Lee, G.Q.; Brumme, C.J.; Hunt, P.W.; Martin, J.N.; Bangsberg, D.R.; Ndung’u, T.; et al. Variation in HIV-1 Nef function within and among viral subtypes reveals genetically separable antagonism of SERINC3 and SERINC5. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruize, Z.; van Nuenen, A.C.; van Wijk, S.W.; Girigorie, A.F.; van Dort, K.A.; Booiman, T.; Kootstra, N.A. Nef Obtained from Individuals with HIV-1 Vary in Their Ability to Antagonize SERINC3- and SERINC5-Mediated HIV-1 Restriction. Viruses 2021, 13, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Karimian Shamsabadi, M.; Stoneham, C.; De Leon, A.; Fares, T.; Guatelli, J.; Jia, X. HIV-1 Nef Uses a Conserved Pocket to Recruit the N-Terminal Cytoplasmic Tail of Serinc3. Viruses 2026, 18, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010005

Karimian Shamsabadi M, Stoneham C, De Leon A, Fares T, Guatelli J, Jia X. HIV-1 Nef Uses a Conserved Pocket to Recruit the N-Terminal Cytoplasmic Tail of Serinc3. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarimian Shamsabadi, Mohammad, Charlotte Stoneham, Amalia De Leon, Tony Fares, John Guatelli, and Xiaofei Jia. 2026. "HIV-1 Nef Uses a Conserved Pocket to Recruit the N-Terminal Cytoplasmic Tail of Serinc3" Viruses 18, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010005

APA StyleKarimian Shamsabadi, M., Stoneham, C., De Leon, A., Fares, T., Guatelli, J., & Jia, X. (2026). HIV-1 Nef Uses a Conserved Pocket to Recruit the N-Terminal Cytoplasmic Tail of Serinc3. Viruses, 18(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010005