The Forgotten History of Bacteriophages in Bulgaria: An Overview and Molecular Perspective on Their Role in Addressing Antibiotic Resistance and Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Bacteriophage Structure and Its Role in Phage Therapy

1.1.1. Overview of Bacteriophage Structure

| Morphological Type | Tail Structure | Key Morphological Features | Functional Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Myovirus | Long, contractile tail | Large head, thick contractile tail [23] | Strong infection force; can inject DNA thought thick capsules; often broad host range [24,25] |

| Siphovirus | Long, non-contractile tail | Flexible, thin tail; small to medium head [23] | Slower DNA injection, typically narrower host range; often more stable in certain conditions [25] |

| Podovirus | Short, stubby tail | Very small tail; compact structure [23] | Fast DNA injection; often used in synthetic phage platforms; efficient in dense environments [24] |

| Inovirus | Filamentous (no head-tail) | Long, thread-like; non-lytic release [23] | Typically temperate; release without lysis; not used therapeutically due to integration risk [25] |

1.1.2. Mechanisms of Action

1.2. Historical Background

1.2.1. Discovery and Origin of Bacteriophages

1.2.2. Bacteriophage Research History in Bulgaria

1.3. Current Trends and Future Directions

1.3.1. Recent Research Trends in Bacteriophage Application

1.3.2. Global Advancements in Bacteriophage Research: The Contrast with Bulgaria

1.3.3. Bacteriophage Therapy and Regulatory Oversight in the EU

1.3.4. Revisiting Bulgarian Phage Research

1.3.5. Today’s Application and Challenges in Phage Therapy

2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clokie, M.R.J.; Millard, A.D.; Letarov, A.V.; Heaphy, S. Phages in nature. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, P. Phages for phage therapy: Isolation, characterization, and host range breadth. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinbauer, M.G. Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2004, 28, 127–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutter, E.; De Vos, D.; Gvasalia, G.; Alavidze, Z.; Gogokhia, L.; Kuhl, S.; Abedon, S.T. Phage Therapy in Clinical Practice: Treatment of Human Infections. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010, 11, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortright, K.E.; Chan, B.K.; Koff, J.L.; Turner, P.E. Phage Therapy: A Renewed Approach to Combat Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, W.C. The strange history of phage therapy. Bacteriophage 2012, 2, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.M.; Koskella, B.; Lin, H.C. Phage therapy: An alternative to antibiotics in the age of multi-drug resistance. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 8, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, H.D.; Dixon, D.M.; Knisely, J.M.; Palmore, T.N.; Fauci, A.S. WHO Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance; WHO/CDS/CSR/DRS/2001.2; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO’s First Global Report on Antibiotic Resistance Reveals Serious, Worldwide Threat to Public Health; Preprint posted online; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Blasdel, B.G.; Bretaudeau, L.; Buckling, A.; Chanishvili, N.; Clark, J.R.; Corte-Real, S.; Debarbieux, L.; Dublanchet, A.; De Vos, D.; et al. Quality and safety requirements for sustainable phage therapy products. Pharm. Res. 2015, 32, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasovski, V. Isolation, Study, Production of Anthrax Bacteriophages and Development of Their Application in Diagnostics. Ph.D. Thesis, Higher Military Medical Institute, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1969. [Google Scholar]

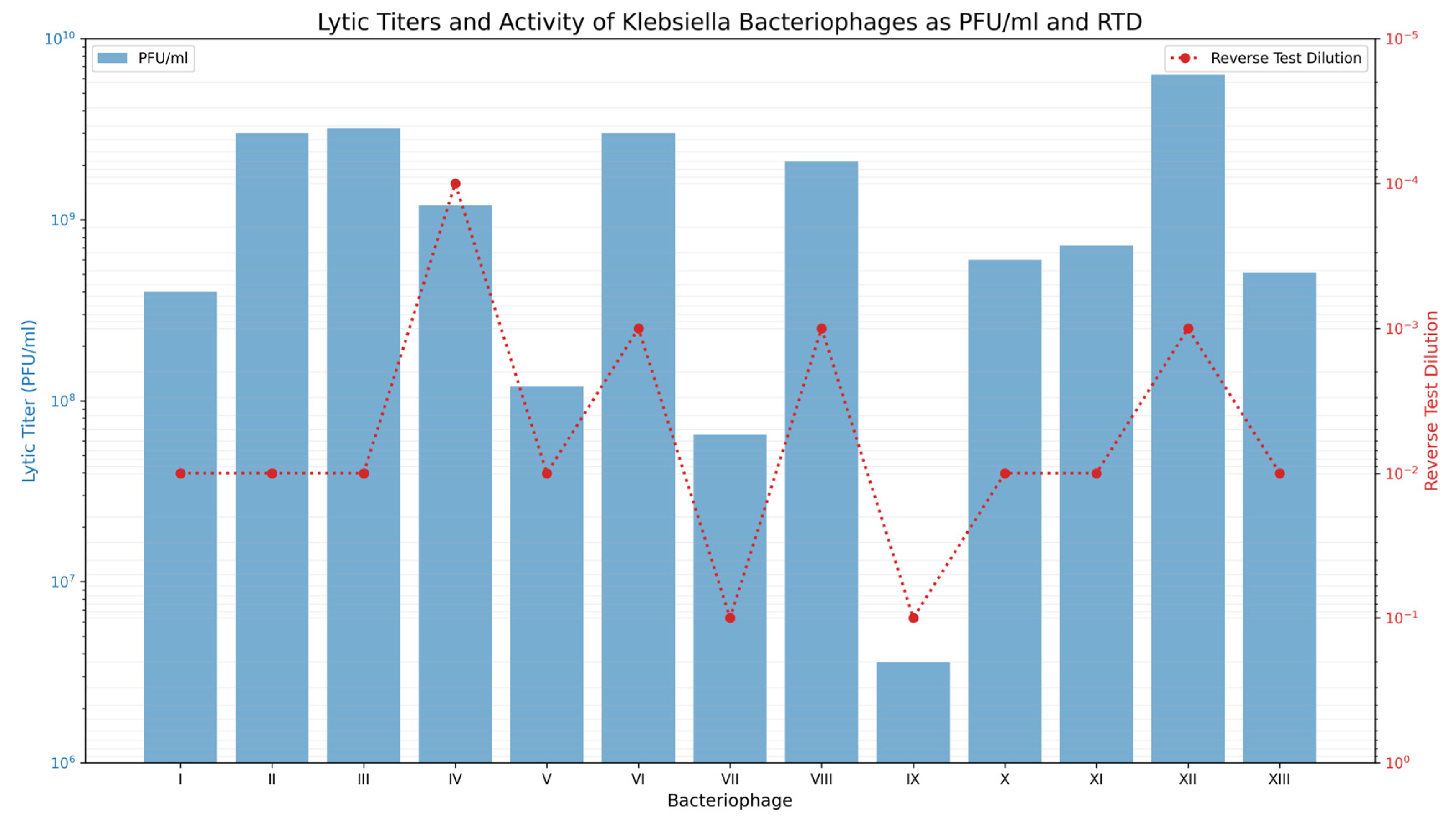

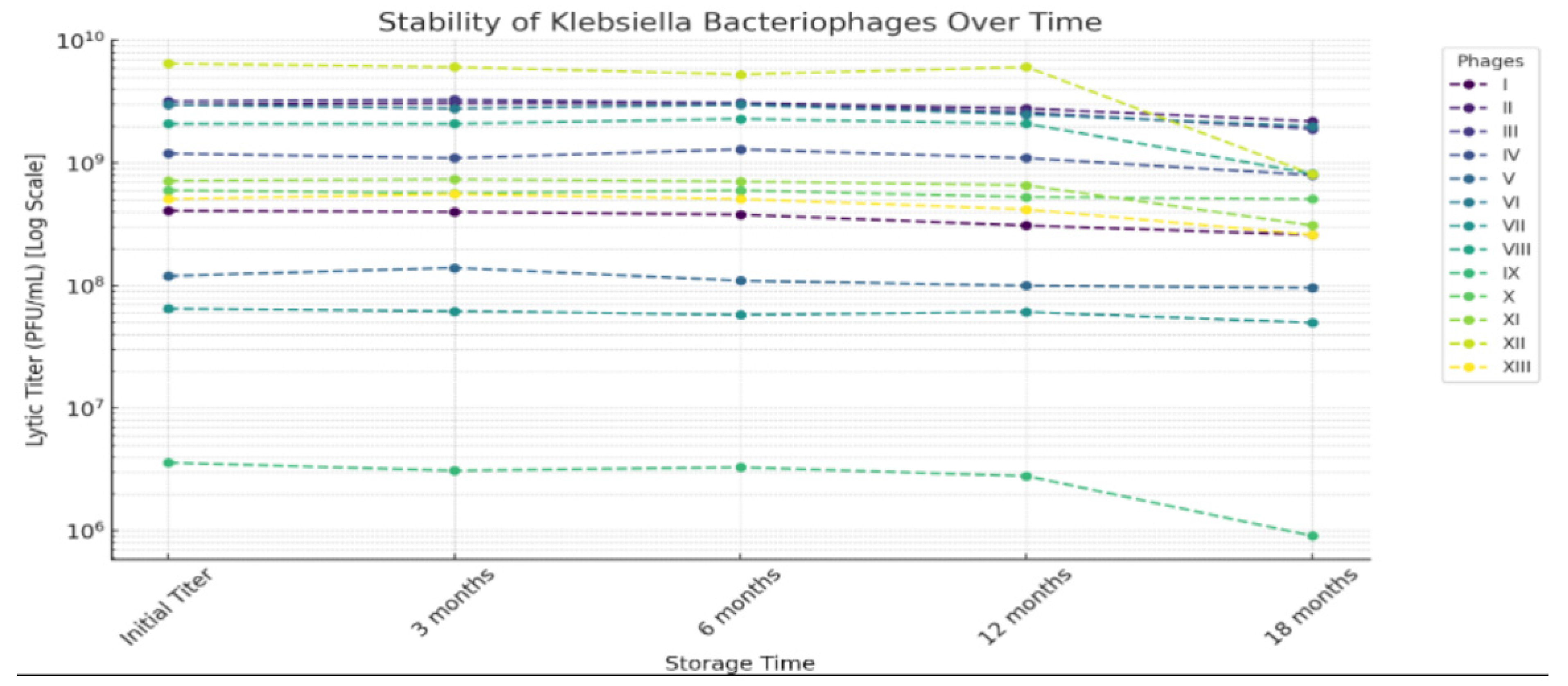

- Kruchmarova–Raycheva, E. Isolation and Study of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Bacteriophages with Regard to Their Application in Epidemiology Practice. Ph.D. Thesis, Medical Academy, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Mollov, D. Phagotyping of S. Enteritidis Using Our Set of Bacteriophages. Ph.D. Thesis, Medical Academy, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, R.; Kutter, E.; Wheat, G.; Blasdel, B.; Kutateladze, M.; Kuhl, S. Bacteriophage treatment of intransigent Diabetic toe ulcers: A case series. J. Wound Care 2016, 25, S27–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaki, S.; Rashel, M.; Uchiyama, J.; Sakurai, S.; Ujihara, T.; Kuroda, M.; Imai, S.; Ikeuchi, M.; Tani, T.; Fujieda, M.; et al. Bacteriophage therapy: A revitalized therapy against bacterial infectious diseases. J. Infect. Chemother. 2005, 11, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teymouri, S.; Yousefi, M.H.; Heidari, S.; Farokhi, S.; Afkhami, H.; Kashfi, M. Beyond antibiotics: Mesenchymal stem cells and bacteriophages-new approaches to combat bacterial resistance in wound infections. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 52, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokine, A.; Rossmann, M.G. Molecular architecture of tailed double-stranded DNA phages. Bacteriophage 2014, 4, e28281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, D.L.; Gaudreault, F.; Chen, W. Functional domains of Acinetobacter bacteriophage tail fibers. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1230997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Lei, T.; Tan, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhao, W.; Zou, H.; Su, J.; Zeng, J.; Zeng, H. Discovery, structural characteristics and evolutionary analyses of functional domains in Acinetobacter baumannii phage tail fiber/spike proteins. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T.; Kuhl, S.J.; Blasdel, B.G.; Kutter, E.M. Phage treatment of human infections. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filik, K.; Szermer-Olearnik, B.; Oleksy, S.; Brykała, J.; Brzozowska, E. Bacteriophage Tail Proteins as a Tool for Bacterial Pathogen Recognition—A Literature Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiman, P.G.; Arisaka, F.; Van Raaij, M.J.; Kostyuchenko, V.A.; Aksyuk, A.A.; Kanamaru, S.; Rossmann, M.G. Morphogenesis of the T4 tail and tail fibers. Virol. J. 2010, 7, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majewska, J.; Miernikiewicz, P.; Szymczak, A.; Kaźmierczak, Z.; Goszczyński, T.M.; Owczarek, B.; Rybicka, I.; Ciekot, J.; Dąbrowska, K. Evolution of the T4 phage virion is driven by selection pressure from non-bacterial factors. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0011523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miernikiewicz, P.; Owczarek, B.; Piotrowicz, A.; Boczkowska, B.; Rzewucka, K.; Figura, G.; Letarov, A.; Kulikov, E.; Kopciuch, A.; Switała-Jeleń, K.; et al. Recombinant expression and purification of T4 phage Hoc, soc, gp23, gp24 proteins in native conformations with stability studies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.Y.K.; Morales, S.; Okamoto, Y.; Chan, H.K. Topical application of bacteriophages for treatment of wound infections. Transl. Res. 2020, 220, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Wang, J. Structural mechanism of bacteriophage lambda tail’s interaction with the bacterial receptor. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Tan, L.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Song, J.; Cheng, L.; Liu, H. Structure of the siphophage neck-Tail complex suggests that conserved tail tip proteins facilitate receptor binding and tail assembly. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- São-José, C. Engineering of phage-derived lytic enzymes: Improving their potential as antimicrobials. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischetti, V.A. Bacteriophage lysins as effective antibacterials. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008, 11, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, J.M.; Nelson, D.; Fischetti, V.A. Rapid killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae with a bacteriophage cell wall hydrolase. Science 2001, 294, 2170–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nang, S.C.; Lin, Y.W.; Petrovic Fabijan, A.; Chang, R.Y.; Rao, G.G.; Iredell, J.; Chan, H.-K.; Li, J. Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of phage therapy: A major hurdle to clinical translation. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabijan, A.P.; Iredell, J.; Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.; Kebriaei, R.; Abedon, S.T. Translating phage therapy into the clinic: Recent accomplishments but continuing challenges. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briers, Y.; Walmagh, M.; Van Puyenbroeck, V.; Cornelissen, A.; Cenens, W.; Aertsen, A.; Oliveira, H.; Azeredo, J.; Verween, G.; Pirnay, J.-P.; et al. Engineered endolysin-based “Artilysins” to combat multidrug-resistant gram-negative pathogens. mBio 2014, 5, e01379-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelcher, M.; Donovan, D.M.; Loessner, M.J. Bacteriophage endolysins as novel antimicrobials. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 1147–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelcher, M.; Powell, A.M.; Becker, S.C.; Camp, M.J.; Donovan, D.M. Chimeric phage lysins act synergistically with lysostaphin to kill mastitis-causing Staphylococcus aureus in murine mammary glands. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 2297–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carratalá, J.V.; Ferrer-Miralles, N.; Garcia-Fruitós, E.; Arís, A. LysJEP8: A promising novel endolysin for combating multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauve, K.; Watson, A.; Oh, J.T.; Swift, S.; Vila-Farres, X.; Abdelhady, W.; Xiong, Y.Q.; LeHoux, D.; Woodnutt, G.; Bayer, A.S.; et al. The Engineered Lysin CF-370 Is Active Against Antibiotic-Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens In Vitro and Synergizes with Meropenem in Experimental Pseudomonas aeruginosa Pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 230, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, N.P.; Vasina, D.V.; Rubalsky, E.O.; Fursov, M.V.; Savinova, A.S.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Usachev, E.V.; Shevlyagina, N.V.; Zhukhovitsky, V.G.; Balabanyan, V.U.; et al. Modulation of Endolysin LysECD7 Bactericidal Activity by Different Peptide Tag Fusion. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T.; García, P.; Mullany, P.; Aminov, R. Editorial: Phage therapy: Past, present and future. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.E.; Wei, H. Novel chimeric lysin with high-Level antimicrobial activity against methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letarov, A.V. History of Early Bacteriophage Research and Emergence of Key Concepts in Virology. Biochemistry 2020, 85, 1093–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summers, W.C. Bacteriophage research: Early history. Bacteriophages Biol. Appl. 2005, 2005, 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Zhao, W.; Zhai, X.; He, Y.; Shu, W.; Qiao, G. Biological characterization and genomic analysis of a novel methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus phage, SauPS-28. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0029523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldová, E. Isolation of bacteriophages active against Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi. J. Hyg. Epidemiol. Microbiol. Immunol. 1964, 8, 375–383. [Google Scholar]

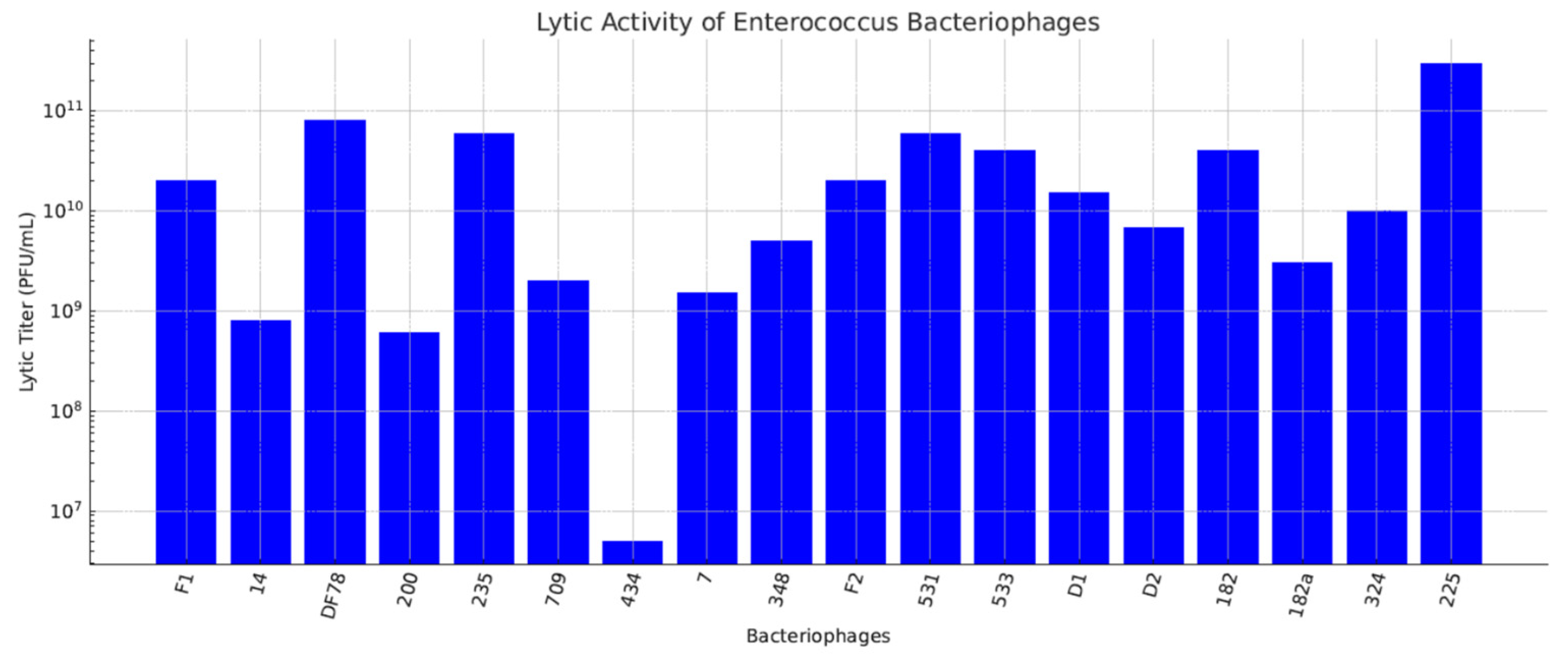

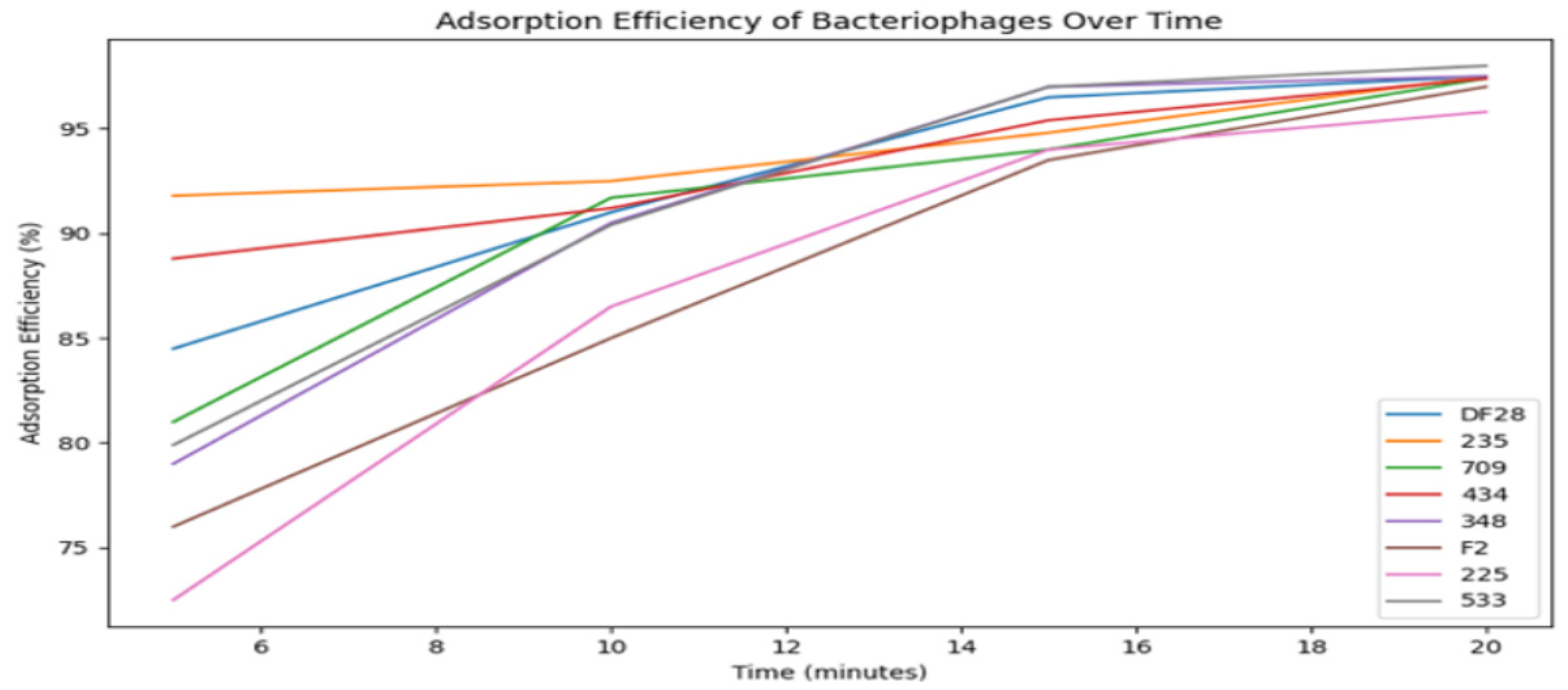

- Paparkova, K. Enterococcal Bacteriophages—Isolation, Study, and Application in the Diagnostics of Enterococci. Ph.D. Thesis, Medical Academy, Sofia, Bulgaria, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Chep, A.; Steyo, B. A method for determining the lytic activity of bacteriophages using test dilutions. Zh. Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 1960, 37, 33–37, (in Russian with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Karaivanov, L. Effect of physical and chemical factors on Pasteurella multocida bacteriophages. Vet. Med. Nauki 1976, 13, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Savov, D.; Karaivanov, L.; Todorova, L. Lysogeny in Escherichia coli isolated from birds and the spectrum of the lytic action of isolated phage. Vet. Med. Nauki 1977, 14, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Trifonova, A.; Bratoeva, M. Combined use of microbiological methods for the intraspecific differentiation of Shigella sonnei. The use of the S. sonnei phage typing method in the People’s Republic of Bulgaria. Zh. Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 1982, 11, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Faddin, J.F. Biochemical Tests for Identification of Medical Bacteria, 3rd ed.; Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2000; Available online: http://lib.ugent.be/catalog/rug01:000694128 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Orskov, F.; Orskov, I. Serotyping of Escherichia coli. Methods Microbiol. 1983, 14, 43–112. [Google Scholar]

- Slavkov, I.; Kolev, K.; Kaloianova, L.; Lalko, I. Prouchvane fagotipovete na izolirani v Bulgariia shtamove S. enteritidis [Phage typing of strains of S. enteritidis isolated in Bulgaria]. Vet. Med. Nauki 1975, 12, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ishlimova, D.I.; Urshev, Z.L.; Stoyancheva, G.D.; Petrova, P.M.; Minkova, S.T.; Doumanova, L.J. Genetic diversity of bacteriophages highly specific for Streptococcus thermophilus strain lbb.a. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2009, 23, 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishlimova, D.; Urshev, Z.; Alexandrov, M.; Doumanova, L. Diversity of Bacteriophages Infecting the Streptococcus Thermophilus Component of Industrial Yogurt Starters in Bulgaria; Bulgarian Academy of Sciences: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barrangou, R.; Fremaux, C.; Deveau, H.; Richards, M.; Boyaval, P.; Moineau, S.; Romero, D.A.; Horvath, P. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 2007, 315, 1709–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksandrova, V.; Ishlimova, D.; Urshev, Z. Classification of Lactobacillus delbrueckii SSP. Bulgaricus phage GB1 into group “B” Lactobacillus delbrueckii bacteriophages based on its partial genome sequencing. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 19, 90–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kizheva, Y.; Eftimova, M.; Rangelov, R.; Micheva, N.; Urshev, Z.; Rasheva, I.; Hristova, P. Broad host range bacteriophages found in rhizosphere soil of a healthy tomato plant in Bulgaria. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shopova, E.; Brankova, L.; Ivanov, S.; Urshev, Z.; Dimitrova, L.; Dimitrova, M.; Hristova, P.; Kizheva, Y. Xanthomonas euvesicatoria-Specific Bacteriophage BsXeu269p/3 Reduces the Spread of Bacterial Spot Disease in Pepper Plants. Plants 2023, 12, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, N.M.; Nguyen, T.D.; Chin, W.H.; Sanborn, J.T.; de Souza, H.; Ho, B.M.; Luong, T.; Roach, D.R. A mechanism-based pathway toward administering highly active N-phage cocktails. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1292618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górski, A.; Borysowski, J.; Miȩdzybrodzki, R. Bacteriophage Interactions with Epithelial Cells: Therapeutic Implications. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 631161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, P.; Sanchez, A.M.; Penke, T.J.R.; Tuson, H.H.; Kime, J.C.; McKee, R.W.; Slone, W.L.; Conley, N.R.; McMillan, L.J.; Prybol, C.J.; et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of LBP-EC01, a CRISPR-Cas3-enhanced bacteriophage cocktail, in uncomplicated urinary tract infections due to Escherichia coli (ELIMINATE): The randomised, open-label, first part of a two-part phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1319–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Djebara, S.; Steurs, G.; Griselain, J.; Cochez, C.; De Soir, S.; Glonti, T.; Spiessens, A.; Berghe, E.V.; Green, S.; et al. Personalized bacteriophage therapy outcomes for 100 consecutive cases: A multicentre, multinational, retrospective observational study. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 1434–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcher, R.; Aurélien, D.; Boris, M.; Laffont-Lozes, P.; Loubet, P.; Lavigne, J.-P.; Bruyere, F.; Sotto, A. Phage therapy in patients with urinary tract infections: A systematic review. Expert Rev. Anti Infect Ther. 2025, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttelmaier, S.; Shuai, W.; Sumner, J.T.; Hartmann, E.M. Phage communities in household-related biofilms correlate with bacterial hosts. Front. Microbiomes 2024, 3, 1396560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, H. Self-assembling T7 phage syringes with modular genomes for targeted delivery of penicillin against beta-lactam-resistant Escherichia coli. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.18687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golembo, M.; Puttagunta, S.; Rappo, U.; Weinstock, E.; Engelstein, R.; Gahali-Sass, I.; Moses, A.; Kario, E.; Cohen, E.B.-D.; Nicenboim, J.; et al. Development of a topical bacteriophage gel targeting Cutibacterium acnes for acne prone skin and results of a phase 1 cosmetic randomized clinical trial. Ski. Health Dis. 2022, 2, e93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Parliment and the Council of the European Union. Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community Code Relating to Medicinal Products for Human Use; The European Parliment and the Council of the European Union: Strasbourg, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products. Guideline on Quality, Safety and Efficacy of Veterinary Medicinal Products Specifically Designed for Phage Therapy; Committee for Veterinary Medicinal Products: Surrey, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Edqm Phage Therapy Medicinal Products. In European Pharmacopoeia, 11th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg Cedex, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST. AST of Phages. Phage Susceptibility Testing (PST): Advancing Standards with EUCAST. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/ast-of-phages (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Aslam, S.; Lampley, E.; Wooten, D.; Karris, M.; Benson, C.; Strathdee, S.; Schooley, R.T. Lessons learned from the first 10 consecutive cases of intravenous bacteriophage therapy to treat multidrug-resistant bacterial infections at a single center in the United States. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedrick, R.M.; Guerrero-Bustamante, C.A.; Garlena, R.A.; Russell, D.A.; Ford, K.; Harris, K.; Gilmour, K.C.; Soothill, J.; Jacobs-Sera, D.; Schooley, R.T.; et al. Engineered bacteriophages for treatment of a patient with a disseminated drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 730–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisek, A.A.; Dąbrowska, I.; Gregorczyk, K.P.; Wyżewski, Z. Phage Therapy in Bacterial Infections Treatment: One Hundred Years After the Discovery of Bacteriophages. Curr. Microbiol. 2017, 74, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordillo Altamirano, F.L.; Barr, J.J. Phage therapy in the postantibiotic era. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32, e00066-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedzybrodzki, R.; Borysowski, J.; Weber-Dabrowska, B.; Fortuna, W.; Letkiewicz, S.; Szufnarowski, K.; Pawełczyk, Z.; Rogóż, P.; Kłak, M.; Wojtasik, E.; et al. Clinical Aspects of Phage Therapy. Adv. Virus Res. 2012, 83, 73–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutateladze, M.; Adamia, R. Bacteriophages as potential new therapeutics to replace or supplement antibiotics. Trends Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 591–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strathdee, S.A.; Hatfull, G.F.; Mutalik, V.K.; Schooley, R.T. Phage therapy: From biological mechanisms to future directions. Cell 2023, 186, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bichet, M.C.; Adderley, J.; Avellaneda-Franco, L.; Gearing, L.J.; Deffrasnes, C.; David, C.; Pepin, G.; Gantier, M.P.; Lin, R.C.; Patwa, R.; et al. Mammalian cells internalize bacteriophages and utilize them as a food source to enhance cellular growth and survival. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, N.; Delattre, R.; Chevallereau, A.; Ricard, J.D.; Debarbieux, L. Phage therapy of pneumonia is not associated with an overstimulation of the inflammatory response compared to antibiotic treatment in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, 00379-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krut, O.; Bekeredjian-Ding, I. Contribution of the Immune Response to Phage Therapy. J. Immunol. 2018, 200, 3037–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyanova, L. Cutibacterium acnes (Formerly Propionibacterium acnes): Friend or Foe? Future Microbiol. 2023, 18, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizheva, Y.; Pandova, M.; Hristova, P. Phage therapy and phage biocontrol—Between science, real application and regulation. Acta Microbiol. Bulg. 2024, 40, 164–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneerselvam, V.P.; Kagithakara Vajravelu, L.; Harikumar Lathakumari, R.; Baskar Vimala, P.; MNair, D.; Thulukanam, J. Bacteriophage-based therapies in oral cancer: A new frontier in oncology. Cancer Pathog. Ther. 2025, 3, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Fan, J.; Pan, F. The power of phages: Revolutionizing cancer treatment. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1290296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, M.; Qi, B. Advancing Phage Therapy: A Comprehensive Review of the Safety, Efficacy, and Future Prospects for the Targeted Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2024, 16, 1127–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeken, G.; Pirnay, J.P.; De Vos, D.; Jennes, S.; Zizi, M.; Lavigne, R.; Casteels, M.; Huys, I. Optimizing the European regulatory framework for sustainable bacteriophage therapy in human medicine. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2012, 60, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penadés, J.R.; Chen, J.; Quiles-Puchalt, N.; Carpena, N.; Novick, R.P. Bacteriophage-mediated spread of bacterial virulence genes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015, 23, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowska, K.; Abedon, S.T. Pharmacologically Aware Phage Therapy: Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Obstacles to Phage Antibacterial Action in Animal and Human Bodies. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2019, 83, 00012-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirnay, J.P.; De Vos, D.; Verbeken, G.; Merabishvili, M.; Chanishvili, N.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Zizi, M.; Laire, G.; Lavigne, R.; Huys, I.; et al. The phage therapy paradigm: Prêt-à-porter or sur-mesure? Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 934–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brives, C.; Pourraz, J. Phage therapy as a potential solution in the fight against AMR: Obstacles and possible futures. Palgrave Commun. 2020, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, J.R.; March, J.B. Bacteriophages and biotechnology: Vaccines, gene therapy and antibacterials. Trends Biotechnol. 2006, 24, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Aldová’s Original Method (1964) [44] | Modifications by Kruchmarova—Raycheva (1973) [12] |

|---|---|---|

| Sample source | Environmental sources (e.g., sewage, soil) | Clinical isolates from hospitalized patients |

| Bacterial host | Standard lab strains | Clinical strains on K. pneumoniae and E. aerogenes |

| Incubation conditions | Unspecified standard times and temperatures | Unchanged (sterile filtration to isolate phages) |

| Filtration | Standard bacterial filtration | Followed by detailed host range testing |

| Detection | Plaque formation on bacterial lawn | Included phage typing using clinical stain panels |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kalvatchev, N.; Khanbabapour, T.; Sakkeer, A.; Tsekov, I.; Delchev, Y.; Strateva, T. The Forgotten History of Bacteriophages in Bulgaria: An Overview and Molecular Perspective on Their Role in Addressing Antibiotic Resistance and Therapy. Viruses 2026, 18, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010038

Kalvatchev N, Khanbabapour T, Sakkeer A, Tsekov I, Delchev Y, Strateva T. The Forgotten History of Bacteriophages in Bulgaria: An Overview and Molecular Perspective on Their Role in Addressing Antibiotic Resistance and Therapy. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalvatchev, Nikolay, Tannaz Khanbabapour, Arit Sakkeer, Iliya Tsekov, Yancho Delchev, and Tanya Strateva. 2026. "The Forgotten History of Bacteriophages in Bulgaria: An Overview and Molecular Perspective on Their Role in Addressing Antibiotic Resistance and Therapy" Viruses 18, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010038

APA StyleKalvatchev, N., Khanbabapour, T., Sakkeer, A., Tsekov, I., Delchev, Y., & Strateva, T. (2026). The Forgotten History of Bacteriophages in Bulgaria: An Overview and Molecular Perspective on Their Role in Addressing Antibiotic Resistance and Therapy. Viruses, 18(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010038