Invertebrate Iridescent Viruses (Iridoviridae) from the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Collection of IIV-Infected Larvae

2.2. Analysis of Field Experiments

2.3. Amplification of IIV Isolates

2.4. Restriction Endonuclease Analysis

2.5. Genome Sequencing of Virus Isolates

2.5.1. Genome Assembly and Annotation

2.5.2. Genome Similarity and Synteny Analyses

2.6. Phylogenetic Reconstruction

3. Results

3.1. Field Collection of IIV-Infected Larvae

3.2. Restriction Endonuclease Analyses

3.3. Genome Assembly and Annotation

3.4. Genome Similarity and Synteny Analyses

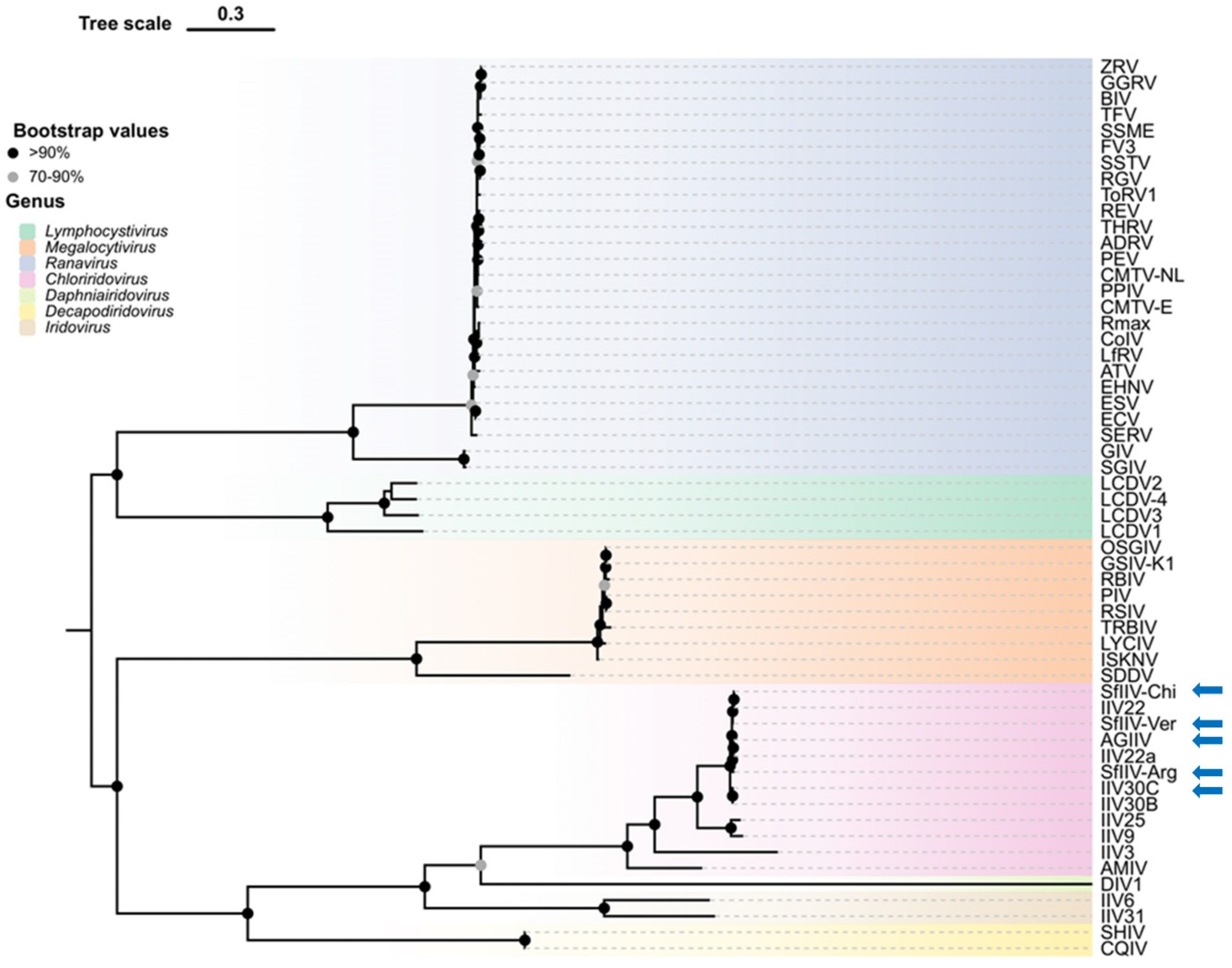

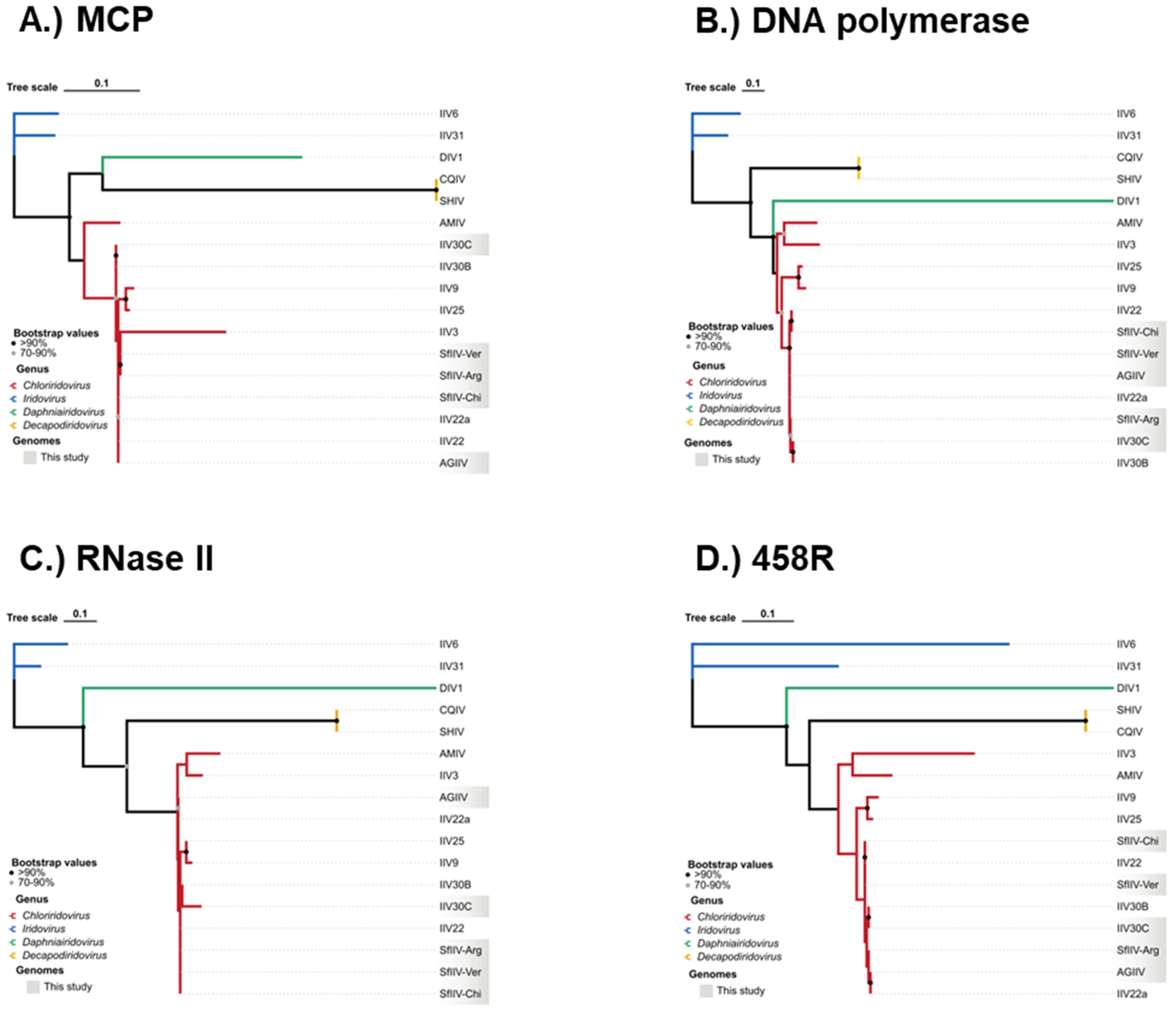

3.5. Phylogenetic Reconstruction

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chinchar, V.G.; Hick, P.; Ince, I.A.; Jancovich, J.K.; Marschang, R.; Qin, Q.; Subramaniam, K.; Waltzek, T.B.; Whittington, R.; Williams, T.; et al. ICTV Report Consortium. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Iridoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 890–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnce, I.A. Iridoviruses of invertebrates (Iridoviridae). In Encyclopedia of Virology, 4th ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 4, pp. 797–803. [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler, P.; Soltau, J.B.; Fischer, M.; Reisner, H.; Scholz, J.; Delius, H.; Darai, G. Molecular cloning and physical mapping of the genome of insect iridescent virus type 6: Further evidence for circular permutation of the viral genome. Virology 1987, 160, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. Patterns of covert infection by invertebrate pathogens: Iridescent viruses of blackflies. Mol. Ecol. 1995, 4, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, K.R.; Hunt, J.; Sadd, B.M.; Sakaluk, S.K.; Oppert, B.; Rosario, K.; Behle, R.W.; Ramirez, J.L. Active and covert infections of cricket iridovirus and Acheta domesticus densovirus in reared Gryllodes sigillatus crickets. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 780796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinchar, V.G.; Hyatt, A.; Miyazaki, T.; Williams, T. Iridoviridae: Poor viral relations no longer. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009, 328, 123–170. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, W.T.; Meagher, R.L., Jr.; Czepak, C.; Groot, A.T. Spodoptera frugiperda: Ecology, evolution, and management options of an invasive species. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2023, 68, 299–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Hernández, O. Costs of cannibalism in the presence of an iridovirus pathogen of Spodoptera frugiperda. Ecol. Entomol. 2006, 31, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Rojas, J.C.; Vandame, R.; Williams, T. Parasitoid-mediated transmission of an iridescent virus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2002, 80, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera, M.L.; Valverde, L.; Popich, S.B.; Ajmat de Toledo, Z.D. Evaluación preliminar de los enemigos naturales de Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) en Tucumán, Argentina. Acta Entomol. Chilena 1995, 19, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T. Invertebrate iridescent viruses. In The Insect Viruses; Miller, L.K., Ball, L.A., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 31–68. [Google Scholar]

- İnce, İ.A.; Özcan, O.; Ilter-Akulke, A.Z.; Scully, E.D.; Özgen, A. Invertebrate iridoviruses: A glance over the last decade. Viruses 2018, 10, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenis, M.; Benelli, G.; Biondi, A.; Calatayud, P.A.; Day, R.; Desneux, N.; Harrison, R.D.; Kriticos, D.; Rwomushana, I.; van den Berg, J.; et al. Invasiveness, biology, ecology, and management of the fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Entomol. Gen. 2023, 43, 187–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Jakob, N.J.; Muller, K.; Bahr, U.; Darai, G. Analysis of the first complete DNA sequence of an invertebrate iridovirus: Coding strategy of the genome of Chilo iridescent virus. Virology 2001, 286, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Cory, J.S. Proposals for a new classification of iridescent viruses. J. Gen. Virol. 1994, 75, 1291–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.K.; Young, V.L.; Kleffmann, T.; Ward, V.K. Genomic and proteomic analysis of invertebrate iridovirus type 9. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 7900–7911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piégu, B.; Guizard, S.; Spears, T.; Cruaud, C.; Couloux, A.; Bideshi, D.K.; Federici, B.A.; Bigot, Y. Complete genome sequence of invertebrate iridovirus IIV30 isolated from the corn earworm, Helicoverpa zea. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2014, 116, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieburth, P.J.; Carner, G.R. Infectivity of an iridescent virus for larvae of Anticarsia gemmatalis (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1987, 49, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadelbacher, E.A.; Adams, J.R.; Faust, R.M.; Tompkins, G.J. An iridescent virus of the bollworm Heliothis zea (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1978, 32, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinard, G.R.; Barnett, O.W.; Carner, G.R. Characterization of an iridescent virus isolated from the velvetbean caterpillar, Anticarsia gemmatalis. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1995, 66, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T. Comparative studies of iridoviruses: Further support for a new classification. Virus Res. 1994, 33, 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R. Filtlong. In GitHub repository. GitHub. 2017. Available online: https://github.com/rrwick/Filtlong (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, M.; Yuan, J.; Lin, Y.; Pevzner, P.A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nature Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gorrie, C.L.; Holt, K.E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017, 13, e1005595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. EggNOG-mapper v2: Functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, P.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y. VIGA: A one-stop tool for eukaryotic virus identification and genome assembly from next-generation-sequencing data. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbad444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallgren, J.; Tsirigos, K.D.; Pedersen, M.D.; Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; Marcatili, P.; Nielsen, H.; Krogh, A.; Winther, O. DeepTMHMM predicts alpha and beta transmembrane proteins using deep neural networks. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stothard, P.; Wishart, D.S. Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 537–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H. CompareM v.0.0.23. Available online: https://github.com/donovan-h-parks/CompareM (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Darling, A.E.; Mau, B.; Perna, N.T. ProgressiveMauve: Multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, H.E.; Metcalf, J.; Penny, E.; Tcherepanov, V.; Upton, C.; Brunetti, C.R. Comparative genomic analysis of the family Iridoviridae: Re-annotating and defining the core set of iridovirus genes. Virol. J. 2007, 4, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emms, D.M.; Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: Phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. t TrimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; Von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiplot Online Graphical Software. 2025. Available online: https://www.chiplot.online (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Scipy 2023. Scipy v. 1.11.1 Online Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/scipy/1.11.1/ (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- ICTV 2025. International Committee on Virus Taxonomy. Family Iridoviridae. Available online: https://ictv.global/report/chapter/iridoviridae/iridoviridae (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Huang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhao, Q.; Pei, G.; An, X.; Guo, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Tong, Y. Isolation and characterization of a novel invertebrate iridovirus from adult Anopheles minimus (AMIV) in China. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 127, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.; Goulson, D.; Caballero, P.; Cisneros, J.; Martínez, A.M.; Chapman, J.W.; Roman, D.X.; Cave, R.D. Evaluation of a baculovirus bioinsecticide for small scale maize growers in Latin America. Biol. Control 1999, 14, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, A.M.; Goulson, D.; Chapman, J.W.; Caballero, P.; Cave, R.D.; Williams, T. Is it feasible to use optical brightener technology with a baculovirus bioinsecticide for resource-poor maize farmers in Mesoamerica? Biol. Control 2000, 17, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowska, A.K.; Vogel, H.; Herrero, S. Increase in gut microbiota after immune suppression in baculovirus-infected larvae. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabodevilla, O.; Villar, E.; Virto, C.; Murillo, R.; Williams, T.; Caballero, P. Intra- and intergenerational persistence of an insect nucleopolyhedrovirus: Adverse effects of sublethal disease on host development, reproduction, and susceptibility to superinfection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 2954–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, T.; Virto, C.; Murillo, R.; Caballero, P. Covert infection of insects by baculoviruses. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; McIntosh, A.H. Dual infection of the Trichoplusia ni cell line with the Chilo iridescent virus (CIV) and Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus. In Invertebrate Tissue Culture: Applications in Medicine, Biology, and Agriculture; Kurstak, E., Maramorosch, K., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976; pp. 391–394. [Google Scholar]

- Arella, M.; Devauchelle, G.; Belloncik, S. Dual infection of a lepidopterean cell line with the cytoplasmic polyhedrosis virus (CPV) and the Chilo iridescent virus (CIV). Ann. L’institut Pasteur/Virol. 1983, 134, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta, R.; Martínez, A.M.; Chapman, J.W.; Magallanes, R.; Goulson, D.; Caballero, P.; Cave, R.D.; Cisneros, J.; Valle, J.; Castillejos, V.; et al. Impact of a nucleopolyhedrovirus bioinsecticide and selected synthetic insecticides on the abundance of insect natural enemies on maize in Southern Mexico. J. Econ. Entomol. 2003, 96, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Ochoa, J.; Carpenter, J.E.; Lezama-Gutiérrez, R.; Foster, J.E.; González-Ramírez, M.; Angel-Sahagún, C.A.; Farías-Larios, J. Natural distribution of hymenopteran parasitoids of Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larvae in Mexico. Fl. Entomol. 2004, 87, 461–472. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Ochoa, J.; Lezama-Gutierrez, R.; Gonzalez-Ramirez, M.; Lopez-Edwards, M.; Rodriguez-Vega, M.A.; Arceo-Palacios, F. Pathogens and parasitic nematodes associated with populations of fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larvae in Mexico. Fl. Entomol. 2003, 86, 244–253. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Nájera, R.E.; Ruiz-Estudillo, R.A.; Sánchez-Yáñez, J.M.; Molina-Ochoa, J.; Skoda, S.R.; Coutiño-Ruiz, R.; Pinto-Ruiz, R.; Guevara-Hernández, F.; Foster, J.E. Occurrence of entomopathogenic fungi and parasitic nematodes on Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) larvae collected in central Chiapas, México. Fl. Entomol. 2013, 96, 498–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullens, B.A.; Velten, R.K.; Federici, B.A. Iridescent virus infection in Culicoides variipennis sonorensis and interactions with the mermithid parasite Heleidomermis magnapapula. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1999, 73, 231–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, R.T.; Poinar, G.O., Jr. Iridoviruses infecting terrestrial isopods and nematodes. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1985, 116, 49–76. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.; Cory, J.S. DNA restriction fragment polymorphism in iridovirus isolates from individual blackflies (Diptera: Simuliidae). Med. Vet. Entomol. 1993, 7, 199–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. Covert iridovirus infection of blackfly larvae. Proc. R. Soc. B 1993, 251, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Piégu, B.; Guizard, S.; Spears, T.; Cruaud, C.; Couloux, A.; Bideshi, D.K.; Federici, B.A.; Bigot, Y. Complete genome sequence of invertebrate iridovirus IIV-25 isolated from a blackfly larva. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, R.M.; Lescott, T.; Kelly, D.C. Serological relationships of an iridescent virus (type 25) recently isolated from Tipula sp. with two other iridescent viruses (types 2 and 22). Virology 1977, 81, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilyurt, A.; Demirbag, Z.; van Oers, M.M.; Nalcacioglu, R. Conserved motifs in the invertebrate iridescent virus 6 (IIV6) genome regulate virus transcription. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2020, 177, 107496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toenshoff, E.R.; Fields, P.D.; Bourgeois, Y.X.; Ebert, D. The end of a 60-year riddle: Identification and genomic characterization of an iridovirus, the causative agent of white fat cell disease in zooplankton. G3 Gen. Genom. Genet. 2018, 8, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltzek, T.B.; Subramaniam, K.; Jancovich, J.K. Ranavirus taxonomy and phylogeny. In Ranaviruses: Emerging Pathogens of Ectothermic Vertebrates; Gray, M.J., Chinchar, V.G., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piégu, B.; Guizard, S.; Yeping, T.; Cruaud, C.; Couloux, A.; Bideshi, D.K.; Federici, B.A.; Bigot, Y. Complete genome sequence of invertebrate iridovirus IIV22A, a variant of IIV22, isolated originally from a blackfly larva. Stand. Gen. Sci. 2014, 9, 940–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Geng, Y.; Zhao, M.; Gu, C.; Fu, L.; He, M.; Xiao, Q.; Xiao, W.; et al. The insights of genomic synteny and codon usage preference on genera demarcation of Iridoviridae family. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 657887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Gu, C.; Zou, X.; Zhao, M.; Xiao, W.; He, M.; He, L.; Yang, Q.; Geng, Y.; Yu, Z. Comparative genomic analysis reveals new evidence of genus boundary for family Iridoviridae and explores qualified hallmark genes. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 3493–3502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, D.R.; Davis, A.J.; Fuller, R.B.; Garner, A.R.; Mileham, A.D.; Serna, J.D.; Brue, D.E.; Harding, C.M.; Dodgen, C.D.; Culpepper, W.; et al. An examination of the Iridovirus core genes for reconstructing Ranavirus phylogenies. Facets 2020, 5, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canuti, M.; Large, G.; Verhoeven, J.T.P.; Dufour, S.C. A novel iridovirus discovered in deep-sea carnivorous sponges. Viruses 2022, 14, 1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piégu, B.; Guizard, S.; Yeping, T.; Cruaud, C.; Asgari, S.; Bideshi, D.K.; Federici, B.A.; Bigot, Y. Genome sequence of a crustacean iridovirus, IIV31, isolated from the pill bug, Armadillidium vulgare. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 1585–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piégu, B.; Asgari, S.; Bideshi, D.; Federici, B.A.; Bigot, Y. Evolutionary relationships of iridoviruses and divergence of ascoviruses from invertebrate iridoviruses in the superfamily Megavirales. Mol. Phylog. Evol. 2015, 84, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Barbosa-Solomieu, V.; Chinchar, V.G. A decade of advances in iridovirus research. Adv. Virus Res. 2005, 65, 173–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T. Natural invertebrate hosts to iridoviruses (Iridoviridae). Neotrop. Entomol. 2008, 37, 615–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancovich, J.K.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Chinchar, V.G. Ranavirus replication: New studies provide answers to old questions. In Ranaviruses: Emerging Pathogens of Ectothermic Vertebrates; Gray, M.J., Chinchar, V.G., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 23–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, O.; Maldonado, G.; Williams, T. An epizootic of patent iridescent virus disease in multiple species of blackflies in Chiapas, Mexico. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2000, 14, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschang, R.E.; Meddings, J.I.; Waltzek, T.B.; Hick, P.; Allender, M.C.; Wirth, W.; Duffus, A.L.J. Ranavirus distribution and host range. In Ranaviruses: Emerging Pathogens of Ectothermic Vertebrates; Gray, M.J., Chinchar, V.G., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 155–230. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.; Cory, J.S. A new record of hymenopterous parasitism of an immature blackfly (Diptera: Simuliidae). Entomol. Gaz. 1991, 42, 220–221. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, X.; He, J.; Li, C. Decapod iridescent virus 1: An emerging viral pathogen in aquaculture. Rev. Aquacult. 2022, 14, 1779–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Jie, Y.; Lu, Z.; Ye, T.; Meng, J.; Liu, C.; Yan, J.; Zheng, Y.; Dong, Z.; Gu, Z. Genomic characterization of Decapod iridescent virus 1 (DIV1) and its host immune responses in Macrobrachium rosenbergii. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2025, 172, 105491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Virus | Original Host | Origen | Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IIV6 | Chilo suppressalis | Japan | R. Webby, J. Kalmakoff | [15] |

| IIV9 | Wiseana cervinata | New Zealand | IVEM Collection | [17] |

| IIV30C | Helicoverpa zea | USA | P. Christian | [20] |

| AgIIV | Anticarsia gemmatalis | Argentina | G. Kinard, C. Moore | [21,22] |

| SfIIV-Arg | Spodoptera frugiperda | Argentina | M.L. Vera | [10] |

| SfIIV-Chi | Spodoptera frugiperda | Chiapas, Mexico | T. Williams | This study |

| SfIIV-Ver | Spodoptera frugiperda | Veracruz, Mexico | M. López-Ortega | This study |

| Treatment | Number of Maize Plots Sampled | Sample Day | Total Number of Larvae Collected | IIV Infected ± SE (%) [n] | SfMNPV Infected ± SE (%) [n] | Parasitism by Parasitoids ± SE (%) [n] | Infection by Nematodes ± SE (%) [n] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | |||||||

| Virus plots | 53 | 2 | 1273 | 0.24 ± 0.14 [3] | 10.05 ± 0.84 [128] | 24.98 ± 1.21 [318] | 6.36 ± 0.68 [81] |

| 54 | 5 | 874 | 0.23 ± 0.16 [2] | 9.84 ± 1.01 [86] | 31.46 ± 1.57 [275] | 3.66 ± 0.64 [32] | |

| 54 | 10 | 662 | 2.42 ± 0.60 [16] | 7.55 ± 1.03 [50] | 16.46 ± 1.44 [109] | 8.91 ± 1.11 [59] | |

| Control plots | 18 | 2 | 456 | 0.00 [0] | 0.00 [0] | 30.92 ± 2.16 [141] | 2.63 ± 0.75 [12] |

| 18 | 5 | 441 | 0.00 [0] | 0.00 [0] | 31.97 ± 2.22 [141] | 7.71 ± 1.27 [34] | |

| 18 | 10 | 248 | 5.24 ± 1.42 [13] | 0.40 ± 0.40 [1] | 15.73 ± 2.31 [39] | 10.08 ± 1.91 [25] | |

| Experiment 2 | |||||||

| Virus plots | 54 | 2 | 748 | 1.07 ± 0.38 [8] | 33.96 ± 1.73 [254] | 26.34 ± 1.61 [197] | 2.01 ± 0.51 [15] |

| 54 | 5 | 761 | 1.05 ± 0.37 [8] | 22.08 ± 1.50 [168] | 18.79 ± 1.42 [143] | 9.59 ± 1.07 [73] | |

| 54 | 10 | 312 | 0.64 ± 0.45 [2] | 6.73 ±1.42 [21] | 12.18 ± 1.85 [38] | 10.90 ± 1.76 [34] | |

| Control plots | 27 | 2 | 451 | 0.22 ± 0.22 [1] | 0.44 ± 0.31 [2] | 25.28 ± 2.05 [114] | 1.55 ± 0.58 [7] |

| 27 | 5 | 324 | 0.93 ± 0.53 [3] | 0.31 ± 0.31 [1] | 19.14 ± 2.19 [62] | 5.86 ± 1.31 [19] | |

| 27 | 10 | 154 | 4.55 ± 1.68 [7] | 1.30 ± 0.91 [2] | 5.19 ±1.79 [8] | 12.99 ± 2.71 [20] |

| Genome | Length (bp) | GC (%) | ORFs | Hypothetical Proteins | Repeats | GC Skew (%) | Cumulative GC Skew Amplitude (%) | ENA Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SfIIV-Chi | 197,661 | 28.1 | 185 | 43 | 87 | 3.43 | 714.09 | ERZ28593071 |

| SfIIV-Ver | 201,630 | 28.2 | 184 | 44 | 66 | 3.52 | 729.18 | ERZ28593070 |

| SfIIV-Arg | 196,053 | 28.1 | 196 | 50 | 80 | −3.52 | 701.61 | ERZ28593069 |

| IIV30C | 200,215 | 28.2 | 209 | 53 | 83 | −2.98 | 621.89 | ERZ28593068 |

| AgIIV | 205,445 | 28.1 | 195 | 47 | 85 | −3.10 | 674.81 | ERZ28593072 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-Heredia, B.; Zamora-Briseño, J.A.; Velasco, L.; Williams, T. Invertebrate Iridescent Viruses (Iridoviridae) from the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Viruses 2026, 18, 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010031

Rodríguez-Heredia B, Zamora-Briseño JA, Velasco L, Williams T. Invertebrate Iridescent Viruses (Iridoviridae) from the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):31. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010031

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-Heredia, Birmania, Jesús Alejandro Zamora-Briseño, Leonardo Velasco, and Trevor Williams. 2026. "Invertebrate Iridescent Viruses (Iridoviridae) from the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda" Viruses 18, no. 1: 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010031

APA StyleRodríguez-Heredia, B., Zamora-Briseño, J. A., Velasco, L., & Williams, T. (2026). Invertebrate Iridescent Viruses (Iridoviridae) from the Fall Armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda. Viruses, 18(1), 31. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010031