1. Introduction

Despite significant advances in blood donor screening for the prevention of transfusion-transmitted infections, hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a threat to the safety of blood recipients around the globe. The residual risk of HBV transmission from transfusion varies considerably between countries. For example, the residual risk of HBV transmission through blood was reported to be 1 in 7.5 million donations in Canada, 45 in 1 million donations in South Africa, 156 in 1 million donations in Mexico, and 1 in 408 donations in Burkina Faso [

1,

2,

3,

4]. This variability is explained by the prevalence of HBV in the population and by the donor screening methods utilized by blood collection agencies [

5]. Many low-income countries rely on rapid testing kits for HBV surface antigen (HBsAg), while most middle- and high-income countries utilize immunoassay (serological) testing for HBsAg combined with testing for the core (HBcAb) and surface (HBsAb) antibodies, with or without nucleic acid testing (NAT). Combining serological testing and NAT provides significant protection against the risk of HBV transmission through transfusion; however, the risk can virtually never be eliminated, mostly secondary to donations within the window period and donations by individuals who have occult hepatitis B infection (OBI). Blood banks face these and other challenges, such as false-positive results that may cause unnecessary deferrals and increased donor anxiety. While guides to the interpretation of serological tests for HBV are commonly available through many resources (

Table 1), this review provides professionals in transfusion medicine, gastroenterology, infectious diseases, and public health with a general overview of the various challenges that may affect testing results. It will equip professionals in these specialties with the knowledge to understand testing limitations, develop an approach to counsel blood donors, determine eligibility, and recognize the potential need for policy updates. We provide an overview of the structure of HBV, genetic mutations that affect detectability, the window period, OBI, vaccine breakthrough infections, sensitivity of tests, and interferences with testing.

2. Hepatitis B Virus Structure

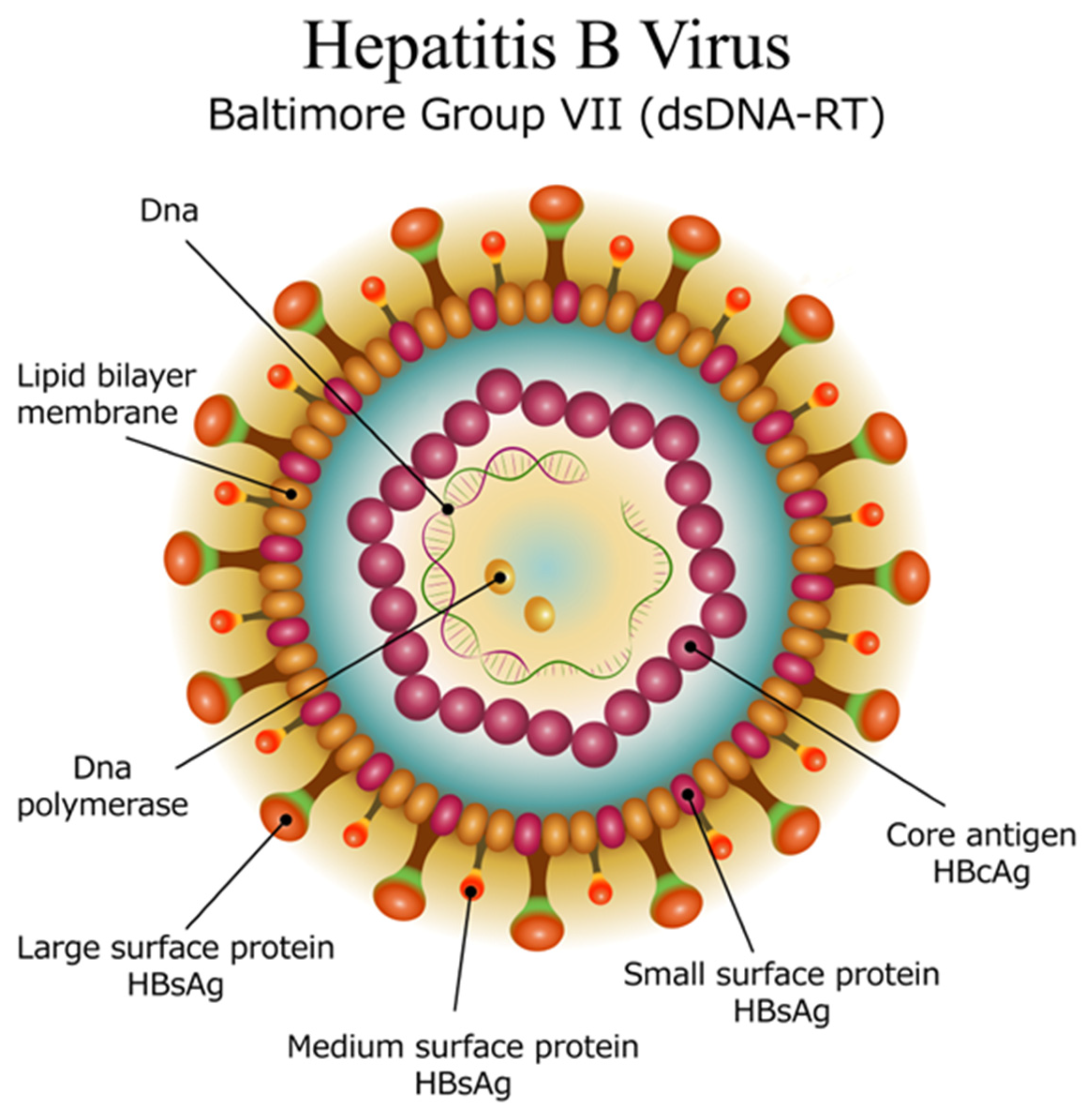

HBV is a small, enveloped virus that belongs to the

Hepadnaviridae family. The lipid bilayered membrane embeds the surface antigen (s antigen), while additional antigens (pre-S 1 and pre-S 2) are attached to its external surface (

Figure 1). Inside the virus is the icosahedral nucleocapsid made of capsomers (core antigens). Inside the nucleocapsid, the DNA of the virus is present in a circular, partially double-stranded form, along with an attached polymerase. The viral genome consists of 4 main regions [

4]:

The precore (pre-C) and core (C) gene, which encodes the core protein (HBcAg) and the e antigen (HBeAg) involved in immune evasion.

The surface (S) gene, which encodes the surface proteins (HBsAg) that form the viral envelope. There are three main surface antigens produced: large (L), middle (M), and small (S), each of which has different roles in the virus’s ability to infect host cells.

The polymerase (P) gene, which encodes the viral polymerase responsible for reverse transcription of the viral RNA into DNA during replication.

The X Gene, which encodes the X protein (HBx) that plays a role in the regulation of viral replication and the modulation of the host cell environment, potentially contributing to oncogenesis.

Ten genotypes of HBV have been recognized (named A to J). While genotype A is commonest in North America and Northern Europe [

8], genotypes B and C are more common in East Asia, and genotype D in the Eastern Mediterranean region [

9].

Several techniques are available for HBV genotyping. Among these, sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of the complete HBV genome remain the gold standard for accurate genotype determination [

10]. Other commonly used approaches include restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis [

11,

12], polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with genotype-specific primers and probes [

13,

14,

15], hybridization-based methods [

16,

17], and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) techniques [

18,

19].

HBV genotyping is primarily conducted in clinical and research settings to guide treatment decisions and support epidemiological studies, as different genotypes can show variable responses to antiviral therapies. In blood banks, genotyping is considered an advanced testing approach that typically utilizes PCR with genotype-specific primers to determine the viral genotype. This method is particularly valuable for assessing potential risks and enhancing blood safety by detecting low viral load cases such as occult HBV infections, identifying “window period” infections, and understanding regional genotype prevalence.

However, HBV genotyping is not routinely included in standard blood donor screening protocols. Only a limited number of commercial discriminatory NAT assays have been approved for use, and many of these are designed to detect only the most common genotypes (A, B, C, and D), which may lead to missed detection of less prevalent variants. Therefore, understanding the geographic distribution of HBV genotypes is crucial for optimizing screening strategies, improving detection accuracy, and ensuring the overall safety of the blood supply.

3. Hepatitis B Virus Gene Mutations

Mutations in the surface gene of HBV can result in altered or truncated HBsAg, preventing recognition of the virus by antibodies used in standard tests [

20]. Structural changes in the HBsAg gene could reduce the expression of the antigen and lead to unstable binding in commercial assays [

21]. For instance, mutations at amino acid position 118 significantly affect the sensitivity of ELISA to detect HBsAg [

22]. Another HBV variant with a novel insertion in the surface protein leads to hyper glycosylation. This mutation impairs the ability of standard diagnostic assays to detect HBV and hinders its recognition by antibodies induced by vaccination or natural infection. These findings suggest that such mutations can significantly impact the efficacy of current HBV diagnostic methods and immune responses, increasing the risk of undetected infections [

23].

Conventional HBsAg assays, including ELISA, and rapid detection devices may fail to detect HBsAg mutants, leading to false-negative results. A study in Pakistan highlighted the inadequacy of these assays in detecting mutant HBsAg alone, with up to 17% detection failure in known HBsAg-positive cases, emphasizing the need for more sensitive and specific testing methods such as PCR [

24]. Thirteen commercial assays underwent performance evaluation in France to assess their ability to detect HBsAg variants. The assays detected the variants with overall positive signals ranging from 62.9% to 97.9%, but specific variants were undetectable by at least one assay [

25].

Some specific mutations in the S gene region, associated with reduced sensitivity of commercial immunoassays, were identified through full gene sequencing. These include I126T, G145R, C124R, C124Y, K141E, and D144A [

26,

27].

S gene mutations do not only affect serological testing; they may impair viral particle secretion, consequently reducing the sensitivity of NAT [

28]. An analysis of blood donations in Southern China reported samples that were reactive to HBsAg using ELISA but nonreactive using NAT. Out of 100,252 donations, 79 samples were further investigated. The study found that 21.5% of those samples were confirmed to be HBsAg-positive, the majority being of genotype B. Specific mutations in the HBV genome, such as T1719G, were identified [

29].

Although not part of current protocols for blood donor screening, DNA sequencing may be useful when evaluating donors with discordant results in HBsAg testing and NAT to identify viral genotype and potential mutations.

4. The Window Period

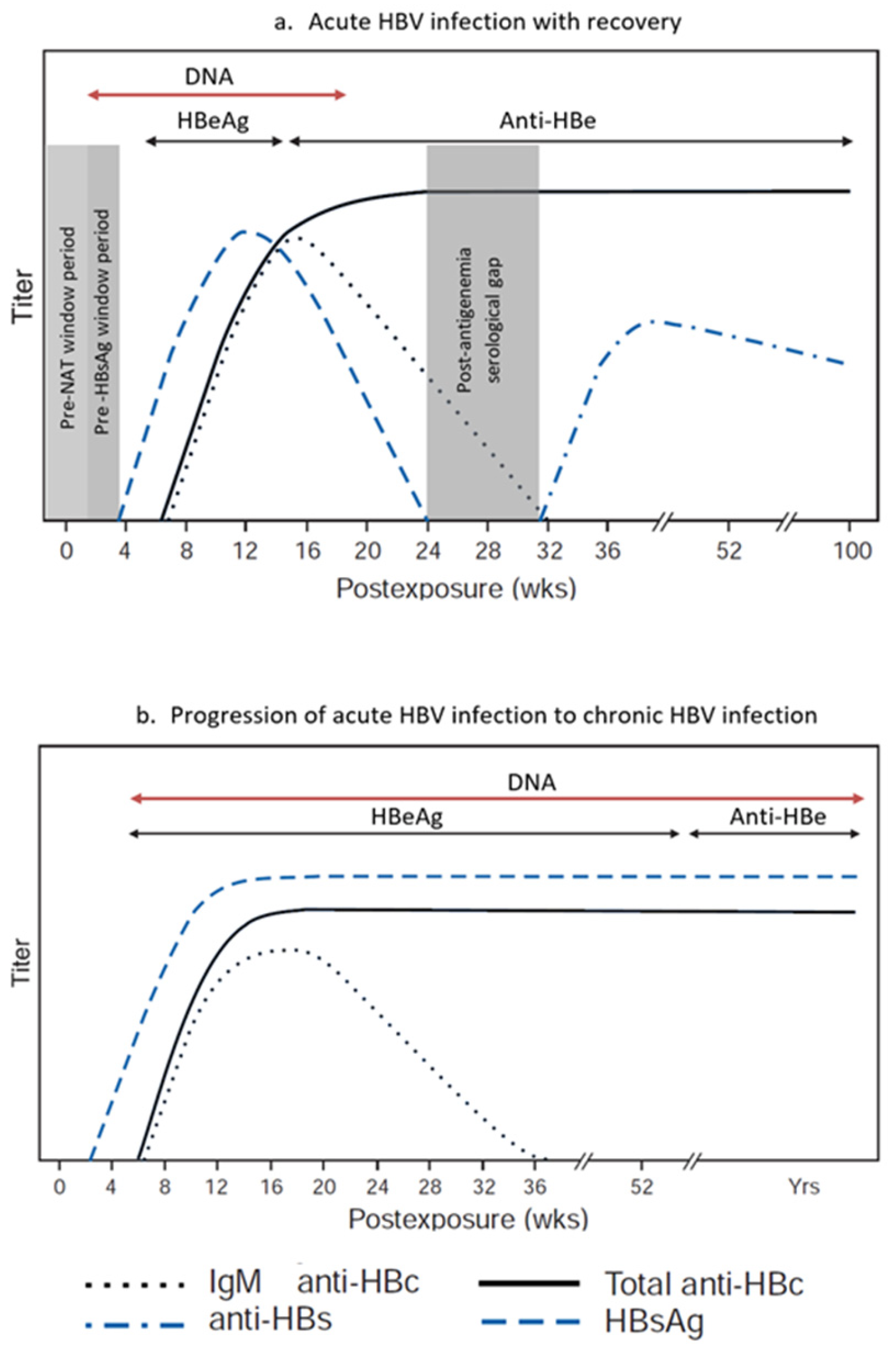

The diagnostic window period is defined as the phase elapsing between the time of infection and the time of detection of the viral marker by the screening assay. The length of the diagnostic window for a particular assay depends on the marker, the screening assay category, the sensitivity of the assay used, and the replication kinetics of the virus during the early infection period [

30].

Among all tests used for blood donor screening for HBV, NAT assays have the shortest window period, reported to range from 10 to 20 days after infection (

Figure 2) [

31]. Depending on the relative sensitivities of the HBsAg and HBV NAT assays used, HBV DNA can be detected 2 to 5 weeks after infection, and up to 40 days (mean 6–15 days) before HBsAg. It is currently well accepted that NAT sensitivity is improved with the use of individual donor NAT (ID-NAT) in comparison with testing in mini-pools (MP-NAT) [

32]. NAT screening in blood donations reduces the risk of transfusion-transmitted infections and shortens the window period for serological marker screening. Therefore, a sensitive NAT screening method for HBV and the recruitment of regular low-risk donors are critical for blood safety [

33].

The use of HBsAg assays with high analytical sensitivity in addition to NAT-based assay is key for the detection of early infection. In one study of a total of 10,981,776 donations, ID-NAT and serology were found to be complementary in detecting HBV infection in first-time donors, but HBV-DNA was superior to HBsAg detection in repeat donors [

34]. NAT yield, defined as the number of donors identified to have the virus only through NAT, is commonly used to estimate residual risk of viral transmission through transfusion in a specific population [

35]. Although donors presenting within the NAT window period may not be detected using screening assays, it is essential to attempt to exclude them using a donor history questionnaire that covers the risk factors of HBV in a particular population.

5. Analytical Sensitivity of Assays for HBsAg

HBsAg analytical sensitivity refers to an assay’s ability to detect the smallest amount of HBsAg in a sample. High sensitivity is essential for early diagnosis and ensuring the safety of blood donations [

36,

37]. To detect blood donors with low viremia, the minimum limit of detection for HBsAg assays recommended by the European Union and World Health Organization (WHO) is 0.13 IU/mL [

31,

38], while it is 0.2 IU/mL according to UK requirements [

39].

Traditional HBsAg assays used in donor screening that meet the various standards are effective but may miss low-level infections, including occult HBV infection (OBI) and vaccine breakthrough cases. Ultra-sensitive assays like the Abbott ARCHITECT

® HBsAg NEXT, with an analytical sensitivity of 0.005 IU/mL, demonstrate up to 14.5-fold greater sensitivity than conventional assays and have shown the ability to detect HBsAg earlier in seroconversion panels and in DNA-positive/HBsAg-negative samples. Notably, this assay detected 7 of 12 HBV DNA-positive samples missed by standard HBsAg tests, without compromising specificity [

40]. Similarly, the Fujirebio Lumipulse-G-HBsAg-Quant assay, with a quantification limit as low 0.0033 IU/mL, identified HBsAg in 25% of previously negative samples from individuals in the window period and with OBI [

41]. These findings suggest that ultra-sensitive assays are particularly valuable in identifying OBIs, early-stage infections, and HBV vaccine breakthrough infections which are critical for ensuring blood safety in high-prevalence regions, especially in regions where NAT is not widely available [

40,

42,

43].

The risks associated with reliance on rapid HBsAg testing kits for donor screening stems from its limited sensitivity. A systematic review and meta-analysis published in 2024 evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of various HBsAg assays highlighted significant improvements in their sensitivity and implications for clinical practice. While chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay had excellent sensitivity, none of the 33 studied rapid diagnostic tests for HBsAg met the limit-of-detection criteria set by the European Union and the WHO [

44]. Newer rapid diagnostic tests have become available since, which meet the required limit of detection, but their use for blood donor screening must be further explored [

45].

6. Interferences

Despite their high sensitivity and specificity, immunoassays are prone to interference by a variety of substances that can be classified into exogenous (process and analyzer-related) and endogenous (sample content-related) factors [

46]. Interfering factors may cause false-positive or false-negative results and must be considered in case of discrepant results. Examples of interferences in immunoassays are provided in

Table 2.

Heterophilic antibodies are naturally occurring, low-avidity human antibodies targeting nonspecific immunogens. They bridge assay antibodies in noncompetitive immunoassays. On the other hand, human anti-animal antibodies (such as human anti-mouse antibodies) are antibodies against a specific animal species that may be formed after exposure to animal immunogens in a social or therapeutic setting (such as after administration of monoclonal antibodies). Both types of antibodies may result in falsely increased or decreased measurements of analytes, leading to false-positive or false-negative results [

47,

48]. The effect of these antibodies may be mitigated through the use of neutralizing material, such as nonimmune mouse IgG. Vaccines, common interventions used in the general public including blood donors, have been recognized to affect specific assays. For example, hepatitis B vaccine can result in a transiently positive result for HBsAg testing up to 14 days post vaccination [

49]. Influenza vaccine has been reported to be associated with false-positive results for serological testing for HCV, HIV, and HTLV, and there are rare reports of them causing false-positive HBsAg results [

50].

Manufacturers usually provide assurance that a specific substance is not expected to provide anomalous results if the substance is present up to specific limits; for example, a reagent manufacturer states that the assay is not affected by icterus (bilirubin < 40 mg/dL), hemolysis (hemoglobin < 2200 mg/dL), lipemia (triglycerides < 2200 mg/dL), and biotin levels below 1200 ng/mL [

51]. Further, test results may be false-positive if sample-to-sample carryover occurs. This phenomenon describes the effect of a sample with a high analyte concentration on subsequent samples because of particle carryover. Carryover is greatly reduced through the use of disposable pipette tips [

52].

7. Limitations of NAT

The introduction of NAT has resulted in significant improvements in blood safety worldwide, mainly through viral detection before seroconversion [

53]. Commercial assays such as cobas TaqScreen MPX v2 and Procleix Ultrio Plus achieve 95% limits of detection (LOD) between 2 and 4 IU/mL. These assays have significantly reduced the window period left by HBsAg testing, narrowing it to an estimated eclipse phase of ~15 days [

43].

The analytical sensitivity of HBV NAT assays is influenced by several technical factors. Primer-probe mismatches, especially in regions with high HBV genetic diversity (e.g., genotypes B, C, and D), can reduce amplification efficiency and lead to false negatives [

43]. Furthermore, nucleic acid loss during extraction and purification is a critical concern. Comparative studies have demonstrated significant variability in DNA recovery across different extraction platforms, with some systems yielding up to twice the amount of viral DNA as others [

54]. The choice of extraction reagents and protocols, such as surfactant-based versus magnetic bead-based methods, also affects the limit of detection and overall assay performance [

55]. NAT’s performance in detecting low levels of viremia is shown to improve with individual-donor NAT when compared with testing in mini pools [

54,

56].

False-positive results in HBV NAT may arise from nonspecific amplification, carryover effect, or borderline reactivity near the assay’s detection threshold. These cases necessitate repeat testing and discriminatory assays to confirm infection status. Importantly, some non-repeatable NAT-reactive donations may represent true low-level infections rather than assay artifacts, requiring cautious interpretation [

28].

To mitigate these limitations, blood centers are increasingly adopting ID-NAT, serial testing, and integrated screening algorithms that combine NAT with serological markers such as anti-HBc. These strategies enhance detection accuracy and reduce residual risk.

Despite their effectiveness, NAT technologies continue to constitute economic challenges to blood suppliers, limiting the ability to use them in many countries [

5].

8. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection

OBI is defined as the presence of replication-competent HBV DNA (i.e., episomal HBV covalently closed circular DNA [cccDNA]) in the liver and/or HBV DNA in the blood of people found to be negative for HBsAg by currently available assays. The viral suppression in OBI, alongside the low replication level of cccDNA, has been explained by the host’s strong immune suppression of HBV replication and gene expression [

57].

Based on the serological profile of hepatitis B antibodies, OBI can be classified as seropositive (Anti-HBc- and/or Anti-HBs-positive) or seronegative (Anti-HBc- and Anti-HBs-negative). The majority of cases of OBI are seropositive [

58]. In seropositive OBI, HBsAg may have been undetected after resolving acute hepatitis B in the presence of a chronic infection status. The duration and detection of HBsAg reactivity are highly variable. The serum level of HBV DNA, when detected, in true OBI is usually low (below 200 IU/mL). However, when the level is comparable to those detected in overt HBV infection, this should be considered false OBI. False OBI occurs mainly due to HBsAg escape mutants detected by some HBsAg assays with poor sensitivity to detect the S gene mutant of HBV [

59]. Seronegative OBI is estimated to constitute from 1% to 20% of OBI patients, who might not be forming HBV antibodies (HBc and HBs) or have been seronegative since the beginning of the infection [

57].

Accurately determining the prevalence of OBI is a real challenge, as it relies on the sensitivity of the testing assays used to test for HBsAg and HBV DNA. Additionally, the prevalence in the population affects the findings. For example, OBI is higher in countries with high HBV prevalence like West Africa and East Asia (1:100–1000) compared with Western Europe, North America, and Australia (below 1:5000); and higher rates are seen in people with existing risk factors like chronic liver disease (which shows an increase of 40–70%) and patients with co-infection with HCV (15–33%) and HIV (10–45%) compared with blood donors and general population rates (less than 0.5%) [

57,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64].

Feasibility of OBI diagnosis depends on the sensitivity of the assays used to detect HBV DNA in liver tissue and/or blood samples [

30]. HBsAg assays with poor sensitivity lead to misdiagnosis of HBV infection compared with ultrasensitive assays [

36]. Recent studies demonstrate that ultrasensitive HBsAg assays with a limit of detection (LOD) of 5.0 to 5.2 mIU/mL, compared with currently used HBsAg assays (with an LOD of 20–50 mIU/mL) have a sensitivity performance close to mini-pool NAT and enhanced detection of OBI [

36].

Furthermore, OBI could be missed through NAT, since the viremia is not consistent. Repeated NAT over time typically yields both positive and negative results. Poorly sensitive HBV DNA assays can also miss OBI, leading to false-negative results, but currently available NAT and real-time PCR-based assays have sufficient performance to detect many OBI cases. Using highly sensitive NAT, investigators from Slovenia have demonstrated that hepatitis B was transmitted from three repeatedly negative HBsAg donors with undetected HBV DNA to nine recipients through blood components [

65]. These cases allowed for the revision of the minimal estimated HBV DNA infectious dose to be approximately 3.4 IU/mL instead of 20 IU/mL. Moreover, this estimation needs further reduction to 0.15 IU/mL in order to prevent HBV transmission [

66].

Detection of anti-HBc is considered a surrogate marker to detect OBI in blood, organ, and tissue donors and in patients who are about to receive immunosuppressive therapy [

67]. Many countries that have low prevalence rates for HBV elect to defer all donors with positive anti-HBc. In other countries, where such a policy could affect blood availability, alternative policies exist, including the determination of donor eligibility based on anti-HBs. Studies from Japan suggest that it is unlikely for blood to transmit HBV if donors are anti-HBc-positive and the level of anti-HBs exceeds 100 mIU/mL (Abbott Architect, Illinois, IL, USA) [

68]. As safe anti-HBs levels vary according to the manufacturer, a safety margin is essential; this led Japan to use a level of 200 mIU/mL as a stratification measure to accept or defer donors with anti-HBc.

9. Vaccine Breakthrough

Vaccination against HBV is a safe and effective way of prevention; however, this method has a few gaps. Infections in vaccinated individuals (vaccine breakthrough) and vaccine non-responsiveness are occasionally seen. As laboratory findings in these cases may vary from usual patterns, they can present threats to blood safety [

69,

70].

The recombinant HBV vaccine is considered 95% to 100% effective in preventing chronic HBV infection for at least 30 years following vaccination. Its efficacy can decrease with advanced age and other factors [

71]. In order to achieve the best and longest-term effect, the whole vaccine series should be completed starting from infancy. However, it is not uncommon to see immunity to HBV fading. A booster vaccine dose may be necessary in some patients to extend the vaccine’s effectiveness. People who develop an anti-HBs titer of at least 10 IU/L (adequate anti-HBs titer) following the completion of a recommended vaccine schedule are considered protected for life. Exceptions are some immunocompromised persons and patients with chronic renal disease, especially those on dialysis. These groups may require periodic boosters with higher doses, if their anti-HBs titer falls below 10 IU/L, as well as regular follow-ups. On the other hand, in immunocompetent individuals, although anti-HBs titers may become nondetectable over time, immunity memory can persist and remain protective. Higher titers of anti-HBs following the initial immunization are associated with longer antibody persistence.

Vaccine breakthrough infections differ from typical acute HBV infection. In acute infection in unvaccinated individuals, the appearance of viral markers in the peripheral blood follows a consistent pattern and order: HBV DNA followed by HBsAg, HBeAg, and then anti-HBc. Resolution of the typical acute infection is marked by loss of serum HBsAg and HBV DNA and the appearance of anti-HBs. In contrast, during vaccine breakthrough infections, HBV DNA becomes detectable in vaccinated individuals who have protective levels of anti-HBs, but this is also limited by the sensitivity of the testing assays. HBsAg detection may be delayed, transient, or absent, and anti-HBc may be negative [

72]. Cases of HBV breakthrough infection have also shown atypical results, including isolated positive anti-HBs [

69].

One of the causes of breakthrough infection is the occurrence of HBsAg escape mutants due to mutations in specific epitopes, such as the “a” determinant region of HBsAg. If this occurs, it may allow the virus to escape neutralizing antibodies formed by the vaccine and HBV immunoglobulin. In Taiwan a study found that the prevalence of HBV S mutants in vaccinated HBV DNA-positive children increased from 8% in 1984 to 23% in 1999 [

73].

10. Conclusions

The complexity of HBV and the multitude of factors affecting the results of various screening assays suggest that blood suppliers need a multi-layered approach combining recognition and deferral of high-risk donors, and utilization of ultra-sensitive HBsAg assays, highly sensitive NAT, and possibly anti-HBc screening. It is essential to adhere to manufacturer instructions regarding the environmental conditions of analyzers, the conditions of reagents, and the proper handling and processing of samples. HBV will continue to pose a threat to the blood supply, but the residual risk varies according to the prevalence of the infection in the donor population and the screening tests used. Pathogen-reduction technologies add layers of safety but are not yet available for all blood components. Healthcare professionals are reminded that transfusion of blood and blood components will continue to carry the inherent risk of transmitting transfusion-transmitted infections. Implementation of patient blood management and hemovigilance systems at the national level is essential to reduce the risk of recipient exposure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.B. and M.A.; methodology, M.A.B., S.E., M.A., M.B., J.K., Y.B.-T. and S.I.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.B., S.E., M.A., M.B., J.K., Y.B.-T. and S.I.H.; writing—review and editing, M.A.B., S.E. and M.A.; visualization, S.E. and M.B.; funding acquisition, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article publishing fee and the fees for editorial assistance are paid by Abbott with no influence on the content of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ramune Sepetiene from Abbott for her support of this work, and Suzan Alkhodair for editorial assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

M.A. is employed by Abbott. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Vermeulen, M.; Swanevelder, R.; Van Zyl, G.; Lelie, N.; Murphy, E.L. An Assessment of Hepatitis B Virus Prevalence in South African Young Blood Donors Born after the Implementation of the Infant Hepatitis B Virus Immunization Program: Implications for Transfusion Safety. Transfusion 2021, 61, 2688–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosa-Jurado, F.; Palencia-Lara, R.; Xicoténcatl-Grijalva, C.; Bernal-Soto, M.; Montiel-Jarquin, Á.; Ibarra-Pichardo, Y.; Rosas-Murrieta, N.H.; Lira, R.; Cortes-Hernandez, P.; Santos-López, G. Donated Blood Screening for HIV, HCV and HBV by ID-NAT and the Residual Risk of Iatrogenic Transmission in a Tertiary Care Hospital Blood Bank in Puebla, Mexico. Viruses 2023, 15, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, S.F.; Yi, Q.-L.; Fan, W.; Scalia, V.; Goldman, M.; Fearon, M.A. Residual Risk of HIV, HCV and HBV in Canada. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2017, 56, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yooda, A.P.; Sawadogo, S.; Soubeiga, S.T.; Obiri-Yeboah, D.; Nebie, K.; Ouattara, A.K.; Diarra, B.; Simpore, A.; Yonli, Y.D.; Sawadogo, A.-G.; et al. Residual Risk of HIV, HCV, and HBV Transmission by Blood Transfusion Between 2015 and 2017 at the Regional Blood Transfusion Center of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. J. Blood Med. 2019, 10, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, M.X.; Faddy, H.M.; Candotti, D.; Groves, J.; Saa, P.; Styles, C.; Adesina, O.; Carrillo, J.P.; Seltsam, A.; Weber-Schehl, M.; et al. International Review of Blood Donation Screening for anti-HBc and Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Transfusion 2024, 64, 2144–2156, Erratum in Transfusion 2025, 65, 648. https://doi.org/10.1111/trf.18094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schillie, S.; Vellozzi, C.; Reingold, A.; Harris, A.; Haber, P.; Ward, J.W.; Nelson, N.P. Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in the United States: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 2018, 67, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B Surveillance Guidance. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/php/surveillance-guidance/hepatitis-b.html (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Stuyver, L.; De Gendt, S.; Van Geyt, C.; Zoulim, F.; Fried, M.; Schinazi, R.F.; Rossau, R. A New Genotype of Hepatitis B Virus: Complete Genome and Phylogenetic Relatedness. Microbiology 2000, 81, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norder, H.; Hammas, B.; Lee, S.-D.; Bile, K.; Courouce, A.-M.; Mushahwar, I.K.; Magnius, L.O. Genetic Relatedness of Hepatitis B Viral Strains of Diverse Geographical Origin and Natural Variations in the Primary Structure of the Surface Antigen. J. Gen. Virol. 1993, 74, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guirgis, B.S.S.; Abbas, R.O.; Azzazy, H.M.E. Hepatitis B Virus Genotyping: Current Methods and Clinical Implications. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 14, e941–e953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannachi, N.; Fredj, N.B.; Bahri, O.; Thibault, V.; Ferjani, A.; Gharbi, J.; Triki, H.; Boukadida, J. Molecular Analysis of HBV Genotypes and Subgenotypes in the Central-East Region of Tunisia. Virol. J. 2010, 7, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizokami, M.; Nakano, T.; Orito, E.; Tanaka, Y.; Sakugawa, H.; Mukaide, M.; Robertson, B.H. Hepatitis B Virus Genotype Assignment Using Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism Patterns. FEBS Lett. 1999, 450, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirschberg, O.; Schüttler, C.; Repp, R.; Schaefer, S. A Multiplex-PCR to Identify Hepatitis B Virus—Genotypes A–F. J. Clin. Virol. 2004, 29, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naito, H.; Hayashi, S.; Abe, K. Rapid and Specific Genotyping System for Hepatitis B Virus Corresponding to Six Major Genotypes by PCR Using Type-Specific Primers. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 362–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logoida, M.; Kristian, P.; Schreiberova, A.; Lenártová, P.D.; Bednárová, V.; Hatalová, E.; Hockicková, I.; Dražilová, S.; Jarčuška, P.; Janičko, M.; et al. Comparison of Two Diagnostic Methods for the Detection of Hepatitis B Virus Genotypes in the Slovak Republic. Pathogens 2021, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomeusz, A.; Schaefer, S. Hepatitis B Virus Genotypes: Comparison of Genotyping Methods. Rev. Med. Virol. 2004, 14, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, S.A.; Martins, R.M.B.; Silva, S.A.; Gomes, D.M.F.; Cardoso, D.D.P.; Vanderborght, B.O.M.; Yoshida, C.F.T. Hepatitis B Virus Infection Profile in Central Brazilian Hemodialysis Population. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. 1998, 40, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usuda, S.; Okamoto, H.; Iwanari, H.; Baba, K.; Tsuda, F.; Miyakawa, Y.; Mayumi, M. Serological Detection of Hepatitis B Virus Genotypes by ELISA with Monoclonal Antibodies to Type-Specific Epitopes in the preS2-Region Product. J. Virol. Methods 1999, 80, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Cheng, H.; Chi, X.; Huang, Q.; Lv, P.; Zhang, W.; Niu, J.; Wen, X.; Liu, Z. ELISA Genotyping of Hepatitis B Virus in China with Antibodies Specific for Genotypes B and C. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Banerjee, A.; Chandra, P.K.; Chakraborty, S.; Basu, S.K.; Chakravarty, R. Detection of a Premature Stop Codon in the Surface Gene of Hepatitis B Virus from an HBsAg and antiHBc Negative Blood Donor. J. Clin. Virol. 2007, 40, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.G.; Ueda, K. Investigation of a Novel Hepatitis B Virus Surface Antigen (HBsAg) Escape Mutant Affecting Immunogenicity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0167871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Nan, Y.; Cai, J.; Xu, J.; Huang, Z.; Cai, X. The Thr to Met Substitution of Amino Acid 118 in Hepatitis B Virus Surface Antigen Escapes from Immune-Assay-Based Screening of Blood Donors. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 1210–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann, F.; Slanina, H.; Roderfeld, M.; Roeb, E.; Trebicka, J.; Ziebuhr, J.; Gerlich, W.H.; Schüttler, C.G.; Schlevogt, B.; Glebe, D. A Novel Insertion in the Hepatitis B Virus Surface Protein Leading to Hyperglycosylation Causes Diagnostic and Immune Escape. Viruses 2023, 15, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooq, A.; Waheed, U.; Zaheer, H.A.; Aldakheel, F.; Alduraywish, S.; Arshad, M. Detection of HBsAg Mutants in the Blood Donor Population of Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0188066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Servant-Delmas, A.; Mercier-Darty, M.; Ly, T.D.; Wind, F.; Alloui, C.; Sureau, C.; Laperche, S. Variable Capacity of 13 Hepatitis B Virus Surface Antigen Assays for the Detection of HBsAg Mutants in Blood Samples. J. Clin. Virol. 2012, 53, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, S.; Liu, X.; Lou, J. Effect of S-Region Mutations on HBsAg in HBsAg-Negative HBV-Infected Patients. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-H.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, P.-J.; Zhang, Y.-L.; Chen, C.-R.; Zheng, Q.-B.; Yeh, S.-H.; Yu, H.; Xue, Y.; Chen, Y.-X.; et al. Influence of Mutations in Hepatitis B Virus Surface Protein on Viral Antigenicity and Phenotype in Occult HBV Strains from Blood Donors. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 720–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Gao, W.; Li, Z.; Liang, H.; Liao, F.; Xie, J.; Li, F.; Wan, Z.; Li, S.; Xu, R.; et al. Comprehensive Evaluation of NAT+/HBsAg− Blood Donors: Confirmation Strategies, Serial Testing Outcomes, and S Gene Mutations Associated with Occult HBV Infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Li, T.; Li, R.; Liu, H.; Zhao, J.; Zeng, J. Molecular Characteristics of HBV Infection among Blood Donors Tested HBsAg Reactive in a Single ELISA Test in Southern China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Hepatitis B and C Testing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-92-4-154998-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dutch, M.; Cheng, A.; Kiely, P.; Seed, C. Revised Nucleic Acid Test Window Periods: Applications and Limitations in Organ Donation Practice. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2024, 26, e14180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Agarwal, N.; Coshic, P.; Borgohain, M.; Chakroborty, S. Sensitivity of Individual and Mini-Pool Nucleic Acid Testing Assessed by Dilution of Hepatitis B Nucleic Acid Testing Yield Samples. Asian J. Transfus. Sci. 2014, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelie, N.; Vermeulen, M.; van Drimmelen, H.; Coleman, C.; Bruhn, R.; Reddy, R.; Busch, M.; Kleinman, S. Direct Comparison of Three Residual Risk Models for Hepatitis B Virus Window Period Infections Using Updated Input Parameters. Vox Sang. 2020, 115, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelie, N.; Bruhn, R.; Busch, M.; Vermeulen, M.; Tsoi, W.-C.; Kleinman, S. Detection of Different Categories of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection in a Multi-regional Study Comparing the Clinical Sensitivity of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen and HBV-DNA Testing. Transfusion 2017, 57, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Estimation of Residual Risk of HIV, HBV or HCV Infections via Cellular Blood Components and Plasma, 67th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-92-4-121013-3. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns, M.C.; Holzmayer, V.; McNamara, A.L.; Sickinger, E.; Schultess, J.; Cloherty, G.A. Improved Detection of Early Acute, Late Acute, and Occult Hepatitis B Infections by an Increased Sensitivity HBsAg Assay. J. Clin. Virol. 2019, 118, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Adequate and Appropriate Donor Screening Tests for Hepatitis B: Hepatitis B Surface Antigen (HBsAg) Assays Used to Test Donors of Whole Blood and Blood Components, Including Source Plasma and Source Leukocytes; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2007.

- The Commission of the European Communities. Commission Decision of 3 February 2009 Amending Decision 2002/364/EC on Common Technical Specifications for in Vitro-Diagnostic Medical Devices (Notified under Document Number C(2009) 565). Off. J. Eur. Union 2009, 52, 34. [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Kingdom (UK) Blood Transfusion and Tissue Transplantation Services Professional Advisory Committee, JPAC. Guidelines for the Blood Transfusion Services in the UK. Available online: https://www.transfusionguidelines.org/red-book/chapter-9-microbiology-tests-for-donors-and-donations-general-specifications-for-laboratory-test-procedures/9-3-specific-assays.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Lou, S.; Taylor, R.; Pearce, S.; Kuhns, M.; Leary, T. An Ultra-Sensitive Abbott ARCHITECT® Assay for the Detection of Hepatitis B Virus Surface Antigen (HBsAg). J. Clin. Virol. 2018, 105, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronier, C.; Candotti, D.; Boizeau, L.; Bomo, J.; Laperche, S.; Thibault, V. The Contribution of More Sensitive Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Assays to Detecting and Monitoring Hepatitis B Infection. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 129, 104507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhns, M.C.; McNamara, A.L.; Holzmayer, V.; Cloherty, G.A. Molecular and Serological Characterization of Hepatitis B Vaccine Breakthrough Infections in Serial Samples from Two Plasma Donors. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candotti, D.; Laperche, S. Hepatitis B Virus Blood Screening: Need for Reappraisal of Blood Safety Measures? Front. Med. 2018, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, A.; Varsaneux, O.; Kelly, H.; Tang, W.; Chen, W.; Boeras, D.I.; Falconer, J.; Tucker, J.D.; Chou, R.; Ishizaki, A.; et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Tests to Detect Hepatitis B Surface Antigen: A Systematic Review of the Literature and Meta-Analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceesay, A.; Lemoine, M.; Cohen, D.; Chemin, I.; Ndow, G. Clinical Utility of the “Determine HBsAg” Point-of-Care Test for Diagnosis of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen in Africa. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2022, 22, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauthier, L.; Plebani, M.; Favresse, J. Interferences in Immunoassays: Review and Practical Algorithm. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. CCLM 2022, 60, 808–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klee, G.G. Human Anti-Mouse Antibodies. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2000, 124, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, I.V.; Levinson, S.S. When Is a Heterophile Antibody Not a Heterophile Antibody? When It Is an Antibody against a Specific Immunogen. Clin. Chem. 1999, 45, 616–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysgaard, C.D.; Morris, C.S.; Drees, D.; Bebber, T.; Davis, S.R.; Kulhavy, J.; Krasowski, M.D. Positive Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Tests Due to Recent Vaccination: A Persistent Problem. BMC Clin. Pathol. 2012, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigham, M.; Ponnampalam, A. Neutralization Positive but Apparent False-Positive Hepatitis B Surface Antigen in a Blood Donor Following Influenza Vaccination. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2014, 50, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University of Iowa Diagnostic Laboratories. Hepatitis B Surface Antigen. Available online: https://www.healthcare.uiowa.edu/path_handbook/rhandbook/test1001.html#:~:text=In%20rare%20cases%2C%20interference%20due,impacted%20by%20high%2Ddose%20biotin (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Armbruster, D.A.; Alexander, D.B. Sample to Sample Carryover: A Source of Analytical Laboratory Error and Its Relevance to Integrated Clinical Chemistry/Immunoassay Systems. Clin. Chim. Acta 2006, 373, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Wang, X.; Feng, F.; Wang, D.; Hu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, M.; Dong, J.; Wu, Y.; et al. Characteristic of HBV Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing Yields from Blood Donors in China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Meng, S.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L.; Li, J. Development of a New Duplex Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction Assay for Hepatitis B Viral DNA Detection. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, K.; Lokteva, L.M.; Akuffo, G.A.; Phyo, Z.; Chhoung, C.; Bunthen, E.; Ouoba, S.; Sugiyama, A.; Akita, T.; Rattana, K.; et al. A Comparative Study of Extraction Free Detection of HBV DNA Using Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate, N-Lauroylsarcosine Sodium Salt, and Sodium Dodecyl Benzene Sulfonate. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Doda, V.; Kirtania, T. Sensitivity of Individual Donor Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT) for the Detection of Hepatitis B Infection by Studying Diluted NAT Yield Samples. Blood Transfus. 2015, 13, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, G.; Locarnini, S.; Pollicino, T.; Levrero, M.; Zoulim, F.; Lok, A.S.; Allain, J.-P.; Berg, T.; Bertoletti, A.; Brunetto, M.R.; et al. Update of the Statements on Biology and Clinical Impact of Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection. J. Hepatol. 2019, 71, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitta, C.; Pollicino, T.; Raimondo, G. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection: An Update. Viruses 2022, 14, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, M.-S.; Kim, Y.J. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection. World J. Hepatol. 2014, 6, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndow, G.; Cessay, A.; Cohen, D.; Shimakawa, Y.; Gore, M.L.; Tamba, S.; Ghosh, S.; Sanneh, B.; Baldeh, I.; Njie, R.; et al. Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Occult Hepatitis B Infection in The Gambia, West Africa. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, J.-H.; Chen, P.-J.; Lai, M.-Y.; Chen, D.-S. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection and Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 4068–4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Singh, S. Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in ART-Naive HIV-Infected Patients Seen at a Tertiary Care Centre in North India. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudawi, H.; Hussein, W.; Mukhtar, M.; Yousif, M.; Nemeri, O.; Glebe, D.; Kramvis, A. Overt and Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Adult Sudanese HIV Patients. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 29, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, J.-P. Global Epidemiology of Occult HBV Infection. Ann. Blood 2016, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candotti, D.; Assennato, S.M.; Laperche, S.; Allain, J.-P.; Levicnik-Stezinar, S. Multiple HBV Transfusion Transmissions from Undetected Occult Infections: Revising the Minimal Infectious Dose. Gut 2019, 68, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locarnini, S.; Raimondo, G. How Infectious Is the Hepatitis B Virus? Readings from the Occult. Gut 2019, 68, 182–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gish, R.G.; Basit, S.A.; Ryan, J.; Dawood, A.; Protzer, U. Hepatitis B Core Antibody: Role in Clinical Practice in 2020. Curr. Hepatol. Rep. 2020, 19, 254–265, Erratum in Curr. Hepatol. Rep. 2020, 19, 499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11901-020-00544-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Yamagishi, N.; Mizokami, M.; Sugiyama, M.; Matsubayashi, K.; Uchida, S.; Nagai, T.; Satake, M. Optimal Titer of anti-HBs in Blood Components Derived from Donors with anti-HBc. Transfusion 2019, 59, 2602–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satake, M.; Yamagishi, N.; Tanaka, A.; Goto, N.; Sakamoto, T.; Yanagino, Y.; Furuta, R.A.; Matsubayashi, K. Transfusion-transmitted HBV Infection with Isolated anti-HBs-positive Blood. Transfusion 2023, 63, 1250–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, S.; Castro, G.M.; Sicilia, P.E.; Carrizo, L.H.; Gallego, S.V. Breakthrough Infection by Hepatitis B Virus in a Vaccinated Blood Donor: An Emerging Threat for Transfusion Safety in Low-endemic Countries? J. Med. Virol. 2024, 96, e29463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Hepatitis B Vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-7-hepatitis-b-vaccine.html (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Kuhns, M.C.; Holzmayer, V.; Anderson, M.; McNamara, A.L.; Sauleda, S.; Mbanya, D.; Duong, P.T.; Dung, N.T.T.; Cloherty, G.A. Molecular and Serological Characterization of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)-Positive Samples with Very Low or Undetectable Levels of HBV Surface Antigen. Viruses 2021, 13, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.-Y.; Chang, M.-H.; Liaw, S.-H.; Ni, Y.-H.; Chen, H.-L. Changes of Hepatitis B Surface Antigen Variants in Carrier Children before and after Universal Vaccination in Taiwan. Hepatology 1999, 30, 1312–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |