Stable Population, Shifting Clades: A 17-Year Phylodynamic Study of IBV GI-19-like Strains in Spain Reveals the Relevance of Frequent Introduction Events, Local Dispersal and Recombination Events

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Spanish Sequences Dataset

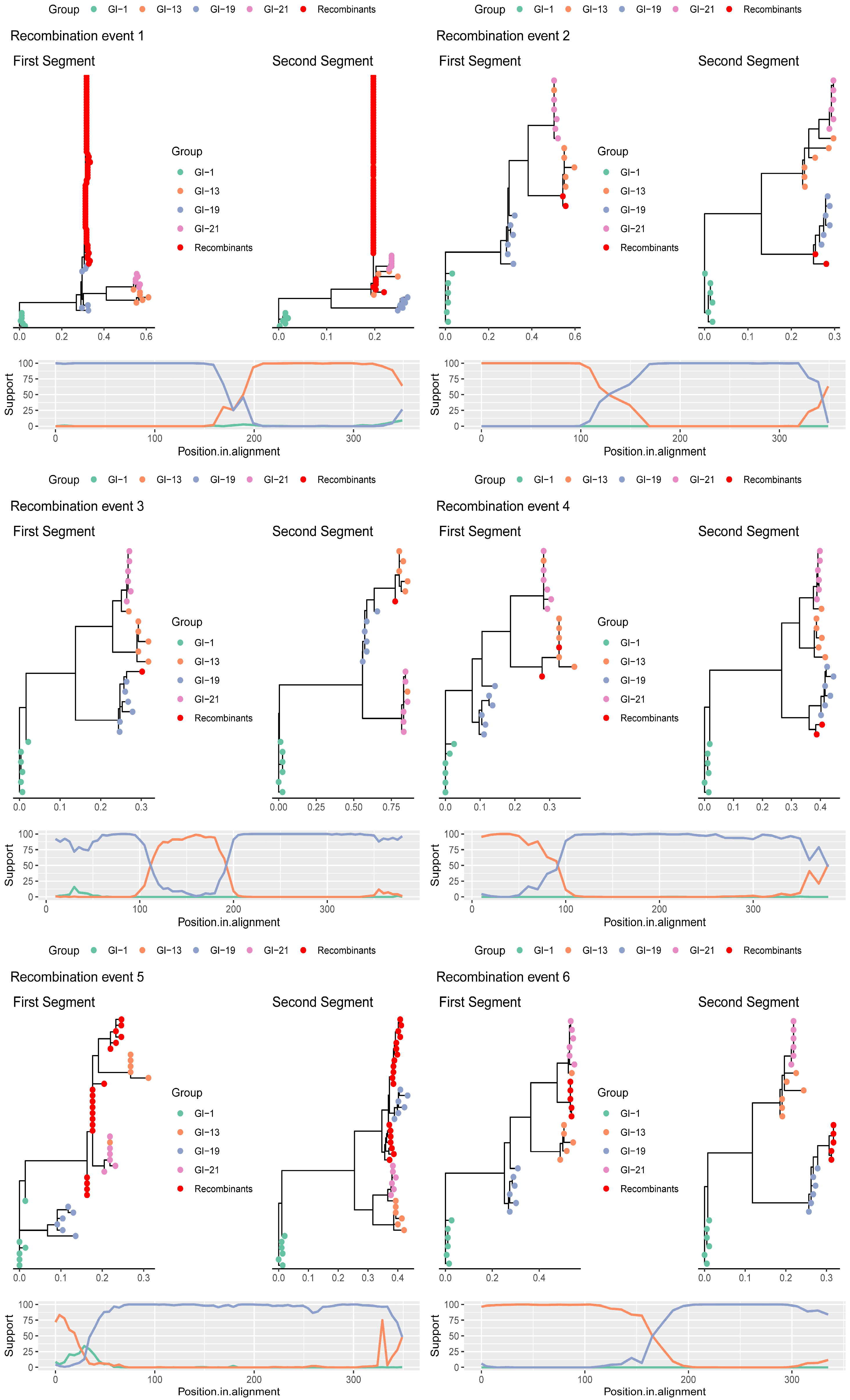

2.2. Recombination Analysis

2.3. Comparison with International Sequences

2.4. Phylodynamic Analysis

3. Results

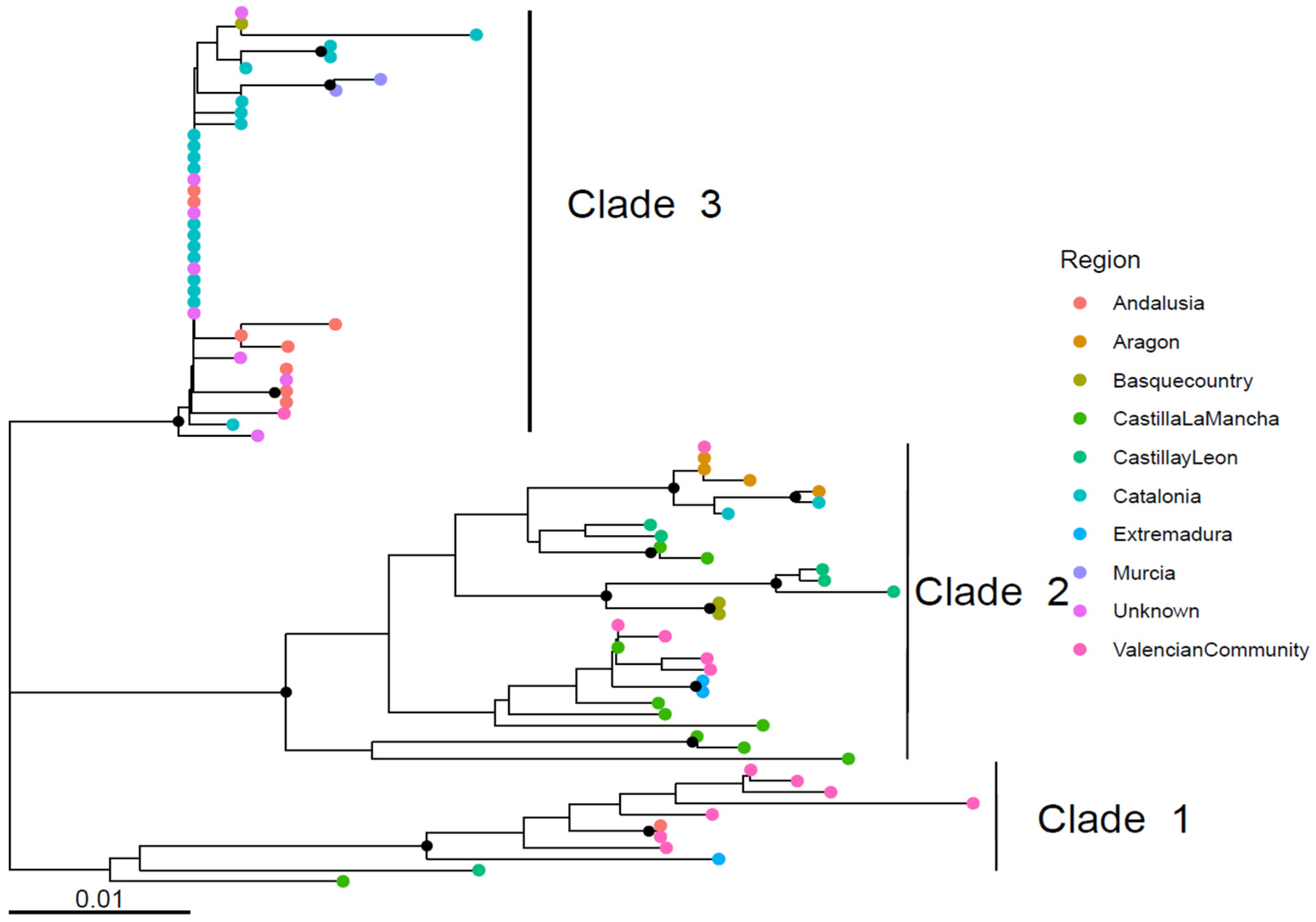

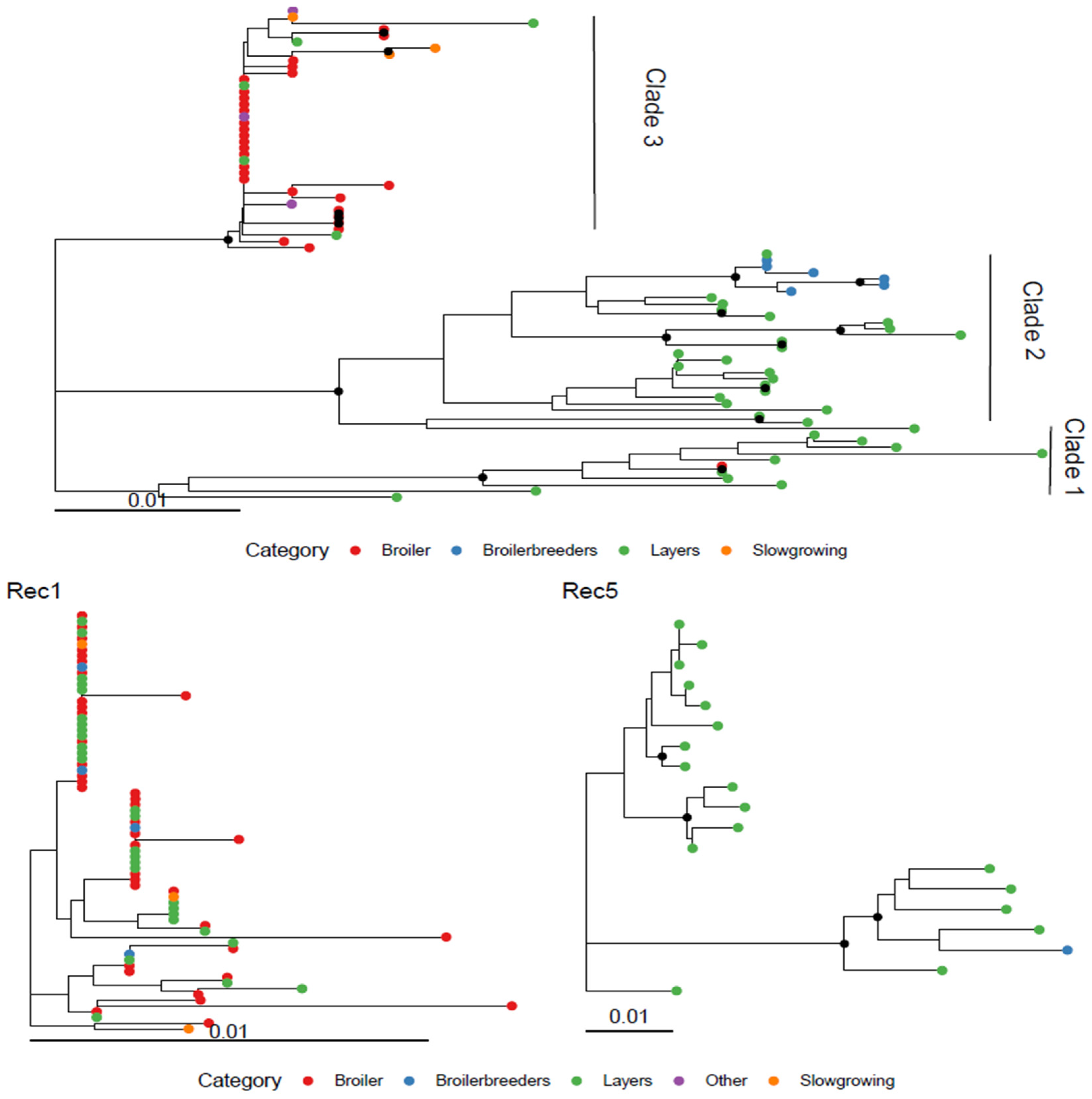

3.1. Spanish GI-19 Clades

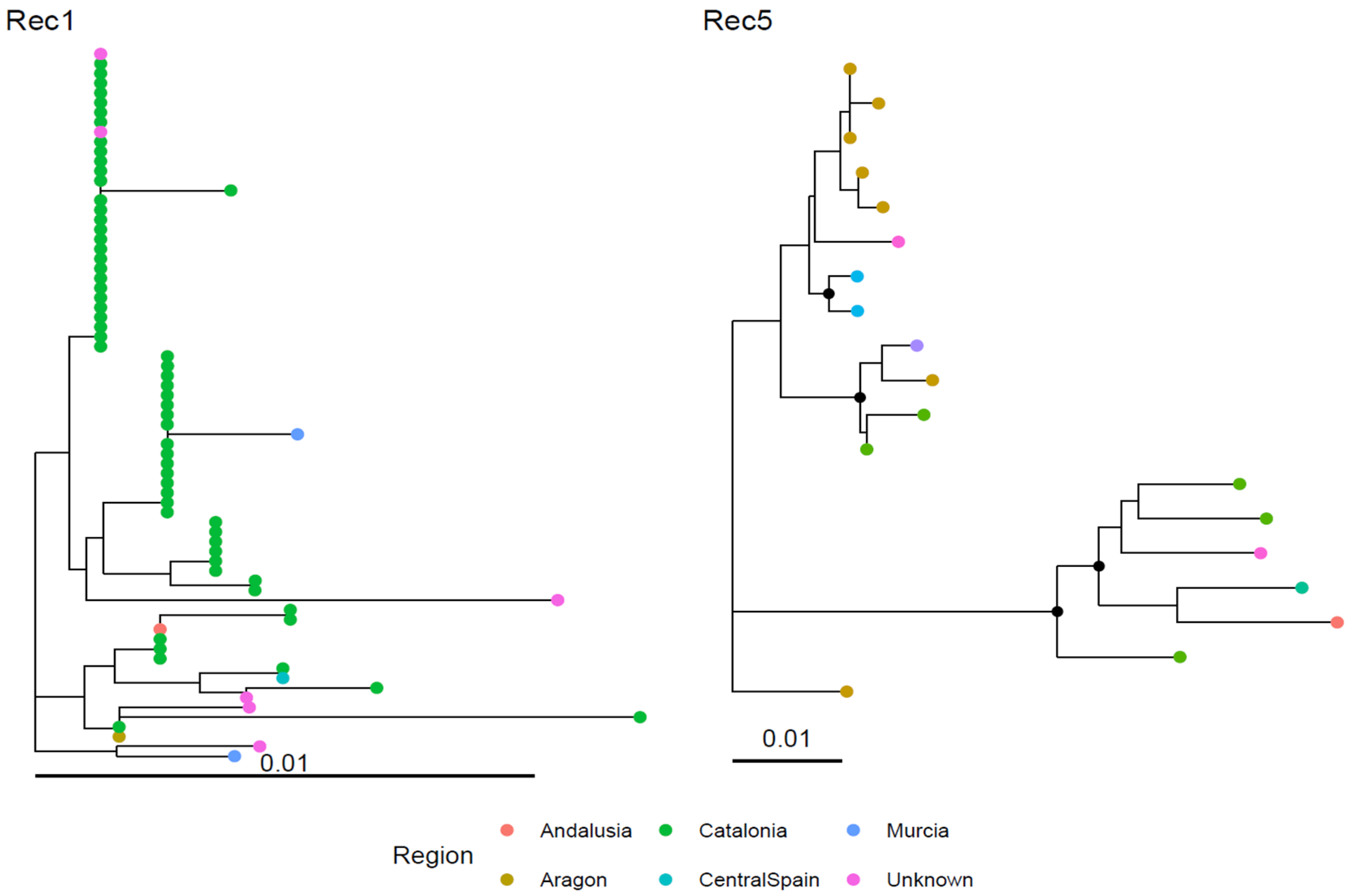

3.2. Recombinant Clusters

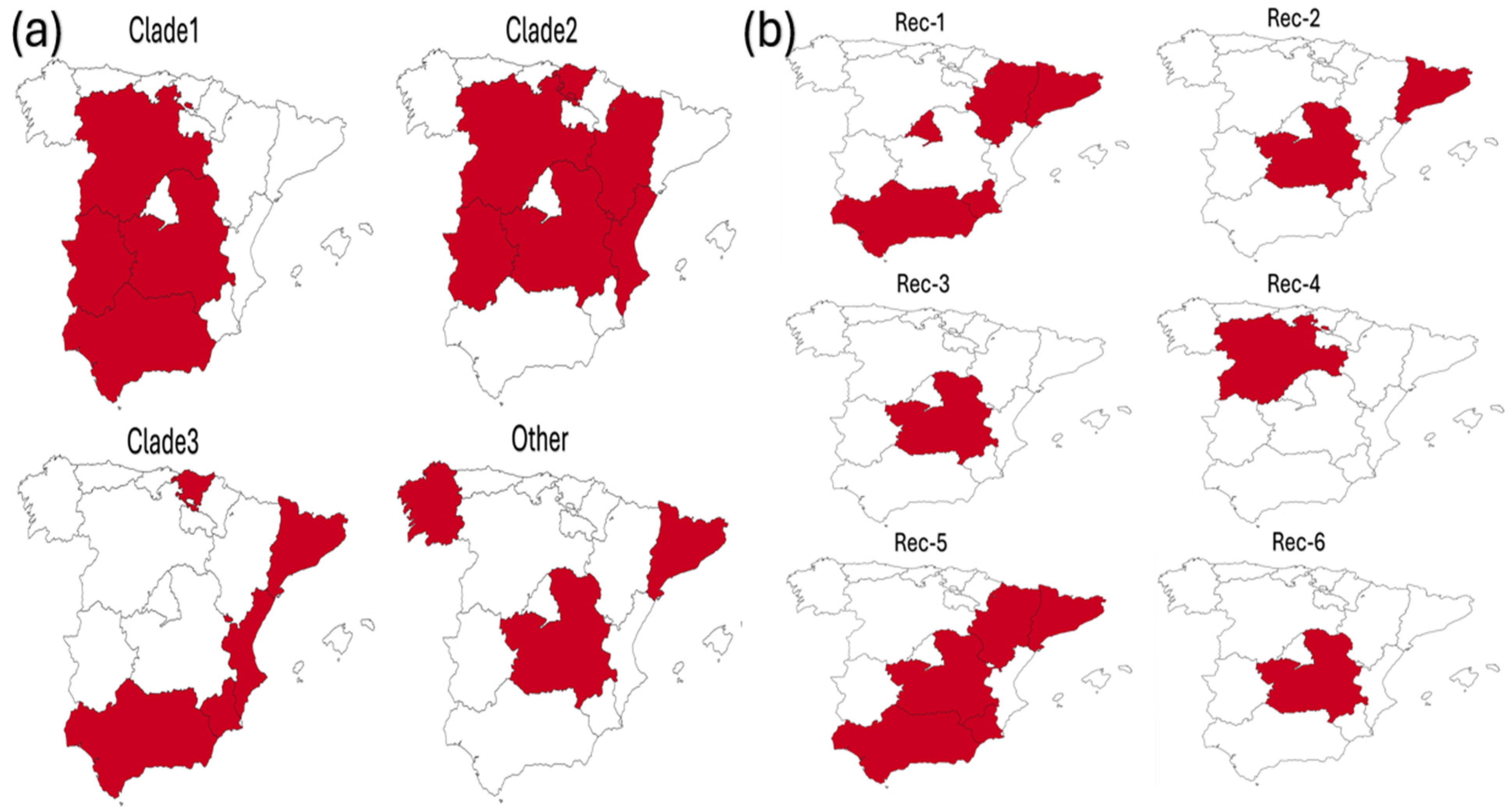

3.3. Geographical and Host Distribution

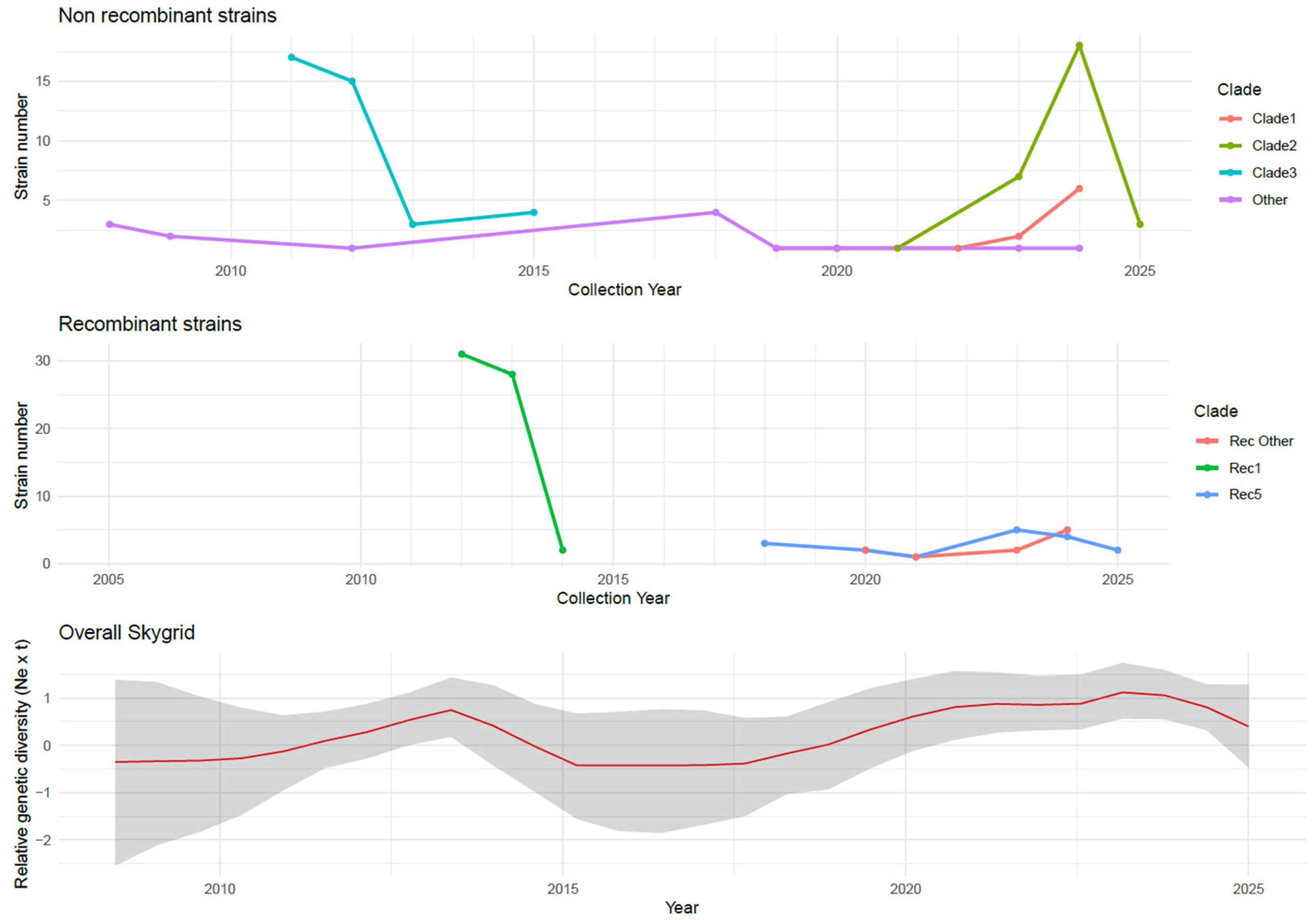

3.4. Phylodynamic Analysis and Dynamics of Major Spanish Non Recombinant and Recombinant Clades

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jackwood, M.W. Review of Infectious Bronchitis Virus Around the World. Avian Dis. 2012, 56, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bande, F.; Arshad, S.S.; Omar, A.R.; Hair-Bejo, M.; Mahmuda, A.; Nair, V. Global Distributions and Strain Diversity of Avian Infectious Bronchitis Virus: A Review. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2017, 18, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoerr, F.J. The Pathology of Infectious Bronchitis. Avian Dis. 2021, 65, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legnardi, M.; Tucciarone, C.M.; Franzo, G.; Cecchinato, M. Infectious Bronchitis Virus Evolution, Diagnosis and Control. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ike, A.C.; Ononugbo, C.M.; Obi, O.J.; Onu, C.J.; Olovo, C.V.; Muo, S.O.; Chukwu, O.S.; Reward, E.E.; Omeke, O.P. Towards Improved Use of Vaccination in the Control of Infectious Bronchitis and Newcastle Disease in Poultry: Understanding the Immunological Mechanisms. Vaccines 2021, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bande, F.; Arshad, S.S.; Bejo, M.H.; Moeini, H.; Omar, A.R. Progress and Challenges toward the Development of Vaccines against Avian Infectious Bronchitis. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 424860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, E.T.; Jackwood, M.W.; Hilt, D.A.; Kissinger, J.C.; Robertson, J.S.; Lemke, C.; Paterson, A.H. Attenuated Live Vaccine Usage Affects Accurate Measures of Virus Diversity and Mutation Rates in Avian Coronavirus Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Virus Res. 2011, 158, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, B. Vaccination against Infectious Bronchitis Virus: A Continuous Challenge. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 206, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toro, H.; van Santen, V.L.; Jackwood, M.W. Invited Review: Genetic Diversity and Selection Regulates Evolution of Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Avian Dis. Dig. 2012, 7, e1–e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, G.; Faustini, G.; Tucciarone, C.M.; Poletto, F.; Tonellato, F.; Cecchinato, M.; Legnardi, M. The Effect of Global Spread, Epidemiology, and Control Strategies on the Evolution of the GI-19 Lineage of Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Viruses 2024, 16, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Geng, Q.; Luo, C. Cryo-EM Structure of Infectious Bronchitis Coronavirus Spike Protein Reveals Structural and Functional Evolution of Coronavirus Spike Proteins. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valastro, V.; Holmes, E.C.; Britton, P.; Fusaro, A.; Jackwood, M.W.; Cattoli, G.; Monne, I. S1 Gene-Based Phylogeny of Infectious Bronchitis Virus: An Attempt to Harmonize Virus Classification. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2016, 39, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, J.J.; De Wit, M.K.; Cook, J.K.A. Infectious Bronchitis Virus Types Affecting European Countries-A Review. Avian Dis. 2021, 65, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.K.A.; Orbell, S.J.; Woods, M.A.; Huggins, M.B. Breadth of Protection of the Respiratory Tract Provided by Different Live-Attenuated Infectious Bronchitis Vaccines against Challenge with Infectious Bronchitis Viruses of Heterologous Serotypes. Avian Pathol. 1999, 28, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, G.; Tucciarone, C.M.; Blanco, A.; Nofrarías, M.; Biarnés, M.; Cortey, M.; Majó, N.; Catelli, E.; Cecchinato, M. Effect of Different Vaccination Strategies on IBV QX Population Dynamics and Clinical Outbreaks. Vaccine 2016, 34, 5670–5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, G.; Naylor, C.J.; Lupini, C.; Drigo, M.; Catelli, E.; Listorti, V.; Pesente, P.; Giovanardi, D.; Morandini, E.; Cecchinato, M. Continued Use of IBV 793B Vaccine Needs Reassessment after Its Withdrawal Led to the Genotype’s Disappearance. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6765–6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legnardi, M.; Franzo, G.; Koutoulis, K.C.; Wiśniewski, M.; Catelli, E.; Tucciarone, C.M.; Cecchinato, M. Vaccine or Field Strains: The Jigsaw Pattern of Infectious Bronchitis Virus Molecular Epidemiology in Poland. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 6388–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunge, V.R.; Kipper, D.; Streck, A.F.; Fonseca, A.S.K.; Ikuta, N. Emergence and Dissemination of the Avian Infectious Bronchitis Virus Lineages in Poultry Farms in South America. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callison, S.A.; Hilt, D.A.; Boynton, T.O.; Sample, B.F.; Robison, R.; Swayne, D.E.; Jackwood, M.W. Development and Evaluation of a Real-Time Taqman RT-PCR Assay for the Detection of Infectious Bronchitis Virus from Infected Chickens. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 138, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, D.; Mawditt, K.; Britton, P.; Naylor, C.J. Longitudinal Field Studies of Infectious Bronchitis Virus and Avian Pneumovirus in Broilers Using Type-Specific Polymerase Chain Reactions. Avian Pathol. 1999, 28, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standley, K. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. (Outlines Version 7). Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergeant, E.S.G. Epitools Epidemiological Calculators; Ausvet Pty Ltd.: Fremantle, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.P.; Murrell, B.; Golden, M.; Khoosal, A.; Muhire, B. RDP4: Detection and Analysis of Recombination Patterns in Virus Genomes. Virus Evol. 2015, 1, vev003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, K.J.; Currie, R.J.W.; Jones, R.C. A Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction Survey of Infectious Bronchitis Virus Genotypes in Western Europe from 2002 to 2006. Avian Pathol. 2008, 37, 247–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, M.; Gascuel, O. Approximate Likelihood-Ratio Test for Branches: A Fast, Accurate, and Powerful Alternative. Syst. Biol. 2006, 55, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baele, G.; Ji, X.; Hassler, G.W.; McCrone, J.T.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Holbrook, A.J.; Lemey, P.; Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A.; et al. BEAST X for Bayesian Phylogenetic, Phylogeographic and Phylodynamic Inference. Nat. Methods 2025, 22, 1653–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchard, M.A.; Kitchen, C.M.R.; Sinsheimer, J.S.; Weiss, R.E. Hierarchical Phylogenetic Models for Analyzing Multipartite Sequence Data. Syst. Biol. 2003, 52, 649–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A.J.; Ho, S.Y.W.; Phillips, M.J.; Rambaut, A. Relaxed Phylogenetics and Dating with Confidence. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, V.; Baele, G. Bayesian Estimation of Past Population Dynamics in BEAST 1.10 Using the Skygrid Coalescent Model. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2019, 36, 2620–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A. Posterior Summarization in Bayesian Phylogenetics Using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno, A.; Franzo, G.; Massi, P.; Tosi, G.; Blanco, A.; Antilles, N.; Biarnes, M.; Majó, N.; Nofrarías, M.; Dolz, R.; et al. A Novel Variant of the Infectious Bronchitis Virus Resulting from Recombination Events in Italy and Spain. Avian Pathol. 2017, 46, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munyahongse, S.; Pohuang, T.; Nonthabenjawan, N.; Sasipreeyajan, J.; Thontiravong, A. Genetic Characterization of Infectious Bronchitis Viruses in Thailand, 2014–2016: Identification of a Novel Recombinant Variant. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 1888–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Han, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, J.; Liu, S.; Ma, D. Multiple Recombination Events between Field and Vaccine Strains Resulted in the Emergence of a Novel Infectious Bronchitis Virus with Decreased Pathogenicity and Altered Replication Capacity. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 1928–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bali, K.; Bálint, Á.; Farsang, A.; Marton, S.; Nagy, B.; Kaszab, E.; Belák, S.; Palya, V.; Bányai, K. Recombination Events Shape the Genomic Evolution of Infectious Bronchitis Virus in Europe. Viruses 2021, 13, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.; Wong, G.; Shi, W.; Liu, J.; Lai, A.C.K.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Bi, Y.; Gao, G.F. Epidemiology, Genetic Recombination, and Pathogenesis of Coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.M.C. Recombination in Large RNA Viruses: Coronaviruses. In Seminars in Virology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; Volume 7, pp. 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Simon-Loriere, E.; Holmes, E.C. Why Do RNA Viruses Recombine? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thor, S.W.; Hilt, D.A.; Kissinger, J.C.; Paterson, A.H.; Jackwood, M.W. Recombination in Avian Gamma-Coronavirus Infectious Bronchitis Virus. Viruses 2011, 3, 1777–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucciarone, C.M.; Franzo, G.; Bianco, A.; Berto, G.; Ramon, G.; Paulet, P.; Koutoulis, K.C.; Cecchinato, M. Infectious Bronchitis Virus Gel Vaccination: Evaluation of Mass-like (B-48) and 793/B-like (1/96) Vaccine Kinetics after Combined Administration at 1 Day of Age. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 3501–3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucciarone, C.M.; Franzo, G.; Berto, G.; Drigo, M.; Ramon, G.; Koutoulis, K.C.; Catelli, E.; Cecchinato, M. Evaluation of 793/B-like and Mass-like Vaccine Strain Kinetics in Experimental and Field Conditions by Real-Time RT-PCR Quantification. Poult. Sci. 2018, 97, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salles, G.B.C.; Pilati, G.V.T.; Savi, B.P.; Dahmer, M.; Muniz, E.C.; Vogt, J.R.; de Lima Neto, A.J.; Fongaro, G. Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV) in Vaccinated and Non-Vaccinated Broilers in Brazil: Surveillance and Persistence of Vaccine Viruses. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, S. Why Are RNA Virus Mutation Rates so Damn High? PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e3000003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzo, G.; Massi, P.; Tucciarone, C.M.; Barbieri, I.; Tosi, G.; Fiorentini, L.; Ciccozzi, M.; Lavazza, A.; Cecchinato, M.; Moreno, A. Think Globally, Act Locally: Phylodynamic Reconstruction of Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV) QX Genotype (GI-19 Lineage) Reveals Different Population Dynamics and Spreading Patterns When Evaluated on Different Epidemiological Scales. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackwood, M.W.; Hall, D.; Handel, A. Molecular Evolution and Emergence of Avian Gammacoronaviruses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2012, 12, 1305–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Shi, W.; Feng, S.; Yuan, L.; Jin, M.; Liang, S.; Wang, X.; Si, H.; Li, G.; Ou, C. A Novel Highly Virulent Nephropathogenic QX-like Infectious Bronchitis Virus Originating from Recombination of GI-13 and GI-19 Genotype Strains in China. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, C.J.; Dijkman, R.; de Wit, J.J.; Bosch, B.J.; Heesterbeek, J.A.P.; van Schaik, G. Genetic Analysis of Infectious Bronchitis Virus (IBV) in Vaccinated Poultry Populations over a Period of 10 Years. Avian Pathol. 2023, 52, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legnardi, M.; Poletto, F.; Franzo, G.; Harper, V.; Bianco, L.; Andolfatto, C.; Blanco, A.; Biarnés, M.; Ramon, L.; Cecchinato, M.; et al. Validation of an Infectious Bronchitis Virus GVIII-Specific RT-PCR Assay and First Detection of IB80-like Strains (Lineage GVIII-2) in Italy. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1514760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petzoldt, D.; Vogel, N.; Bielenberg, W.; Haneke, J.; Bischoff, H.; Liman, M.; Rönchen, S.; Behr, K.-P.; Menke, T. IB80—A Novel Infectious Bronchitis Virus Genotype (GVIII). Avian Dis. 2022, 66, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Han, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Gao, M.; Wu, W.; Shao, Y.; Li, H.; Kong, X.; Liu, S. Serotype Shift of a 793/B Genotype Infectious Bronchitis Coronavirus by Natural Recombination. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 32, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Clade1 | Clade2 | Clade3 | Other | Rec1 | Rec2 | Rec3 | Rec4 | Rec5 | Rec6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broiler | 1 | 0 | 29 | 7 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Broiler breeders | 0 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Layers | 10 | 23 | 5 | 7 | 28 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 18 | 5 |

| Slow growing chicken | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Franzo, G.; Poletto, F.; Legnardi, M.; Baston, R.; Andolfatto, C.; Ramon, L.; Becerra, M.; Biarnés, M.; Cecchinato, M.; Tucciarone, C.M. Stable Population, Shifting Clades: A 17-Year Phylodynamic Study of IBV GI-19-like Strains in Spain Reveals the Relevance of Frequent Introduction Events, Local Dispersal and Recombination Events. Viruses 2026, 18, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010024

Franzo G, Poletto F, Legnardi M, Baston R, Andolfatto C, Ramon L, Becerra M, Biarnés M, Cecchinato M, Tucciarone CM. Stable Population, Shifting Clades: A 17-Year Phylodynamic Study of IBV GI-19-like Strains in Spain Reveals the Relevance of Frequent Introduction Events, Local Dispersal and Recombination Events. Viruses. 2026; 18(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleFranzo, Giovanni, Francesca Poletto, Matteo Legnardi, Riccardo Baston, Cristina Andolfatto, Laura Ramon, Marta Becerra, Mar Biarnés, Mattia Cecchinato, and Claudia Maria Tucciarone. 2026. "Stable Population, Shifting Clades: A 17-Year Phylodynamic Study of IBV GI-19-like Strains in Spain Reveals the Relevance of Frequent Introduction Events, Local Dispersal and Recombination Events" Viruses 18, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010024

APA StyleFranzo, G., Poletto, F., Legnardi, M., Baston, R., Andolfatto, C., Ramon, L., Becerra, M., Biarnés, M., Cecchinato, M., & Tucciarone, C. M. (2026). Stable Population, Shifting Clades: A 17-Year Phylodynamic Study of IBV GI-19-like Strains in Spain Reveals the Relevance of Frequent Introduction Events, Local Dispersal and Recombination Events. Viruses, 18(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/v18010024