Modeling the Complete Dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic of Germany and Its Federal States Using Multiple Levels of Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Approach

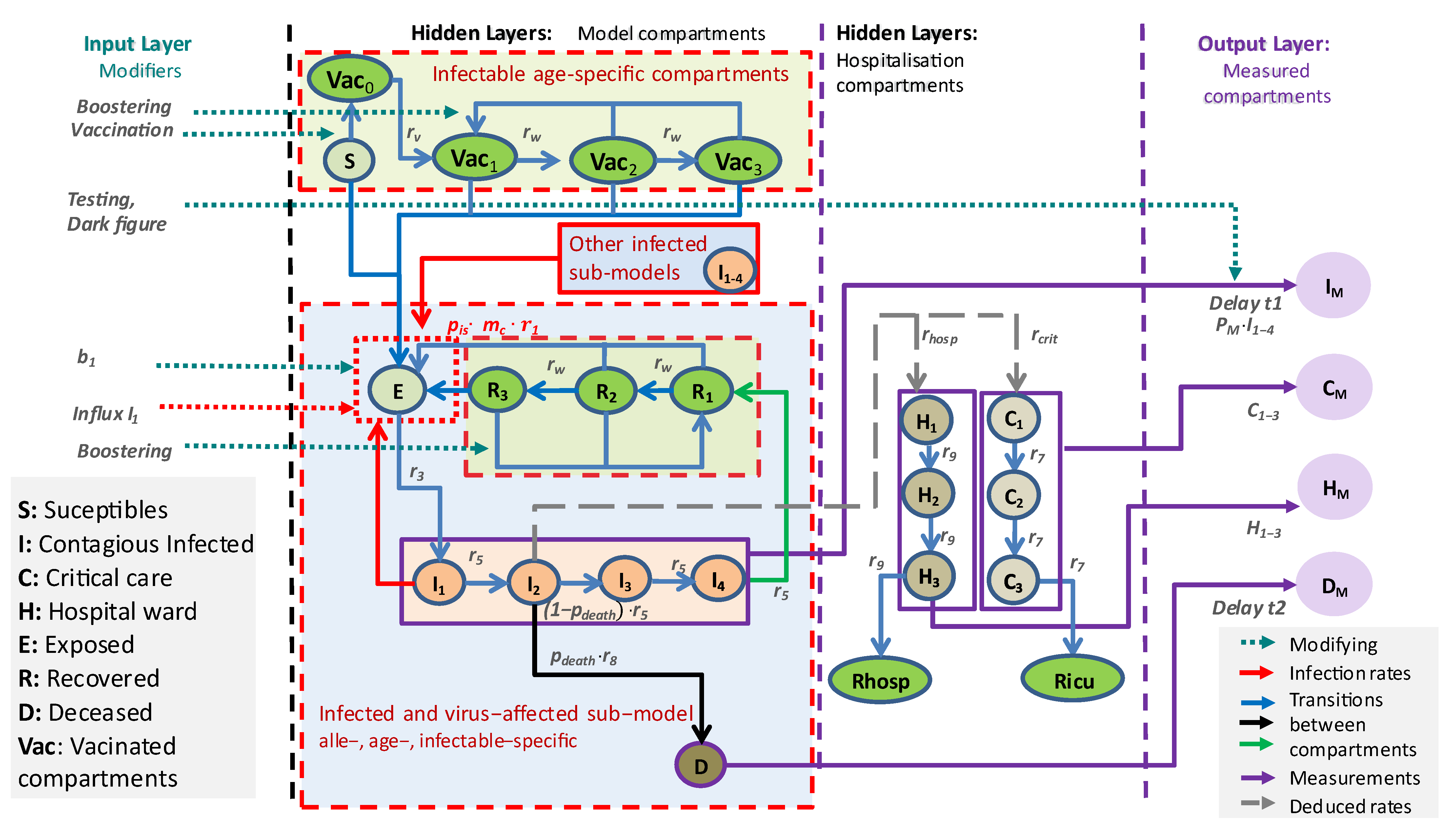

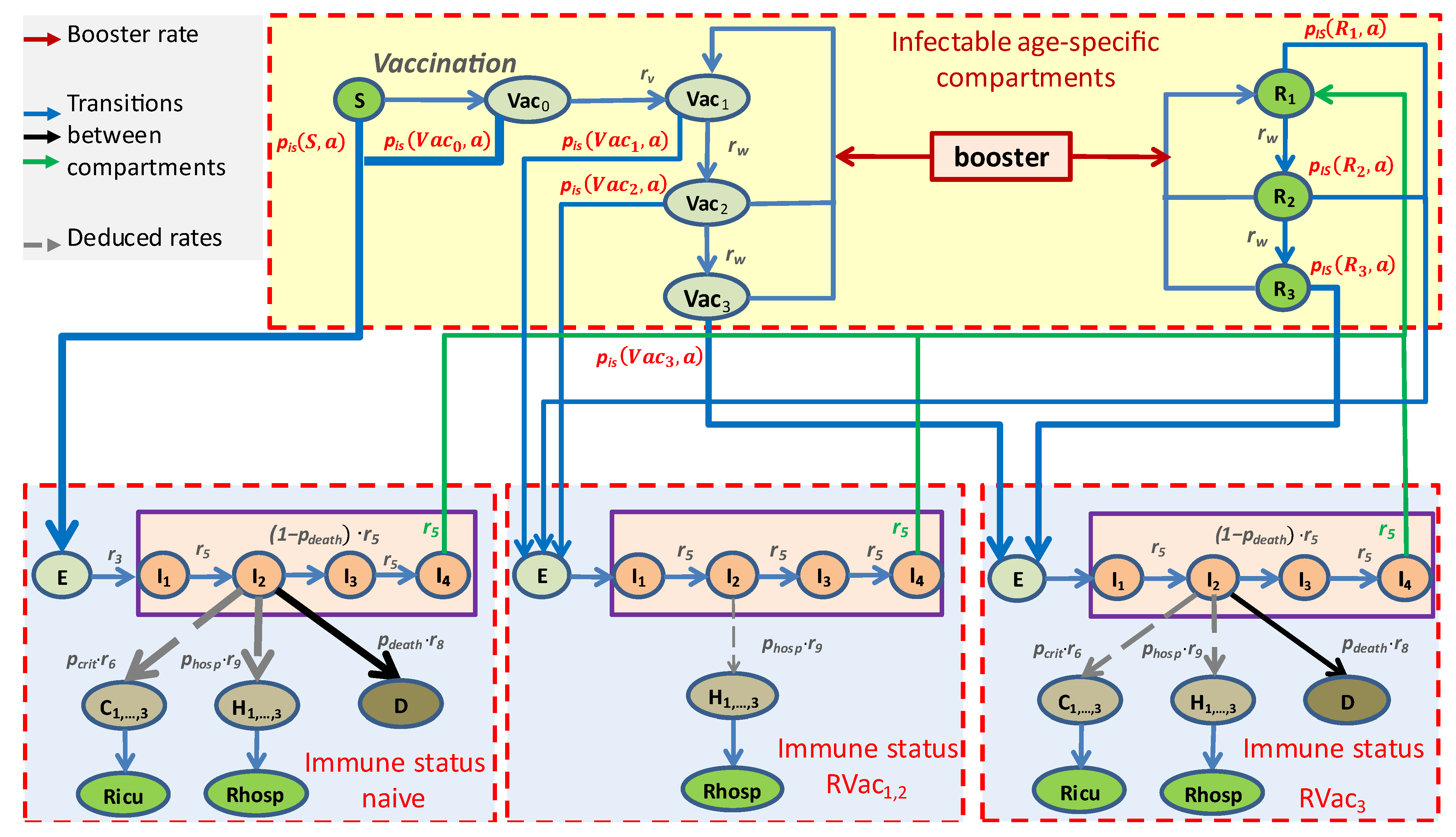

2.2. Concepts and Assumptions of the Core Model

- Five age groups: 1–14 years, 15–34 years, 35–59 years, 60–79 years, and ≥80 years;

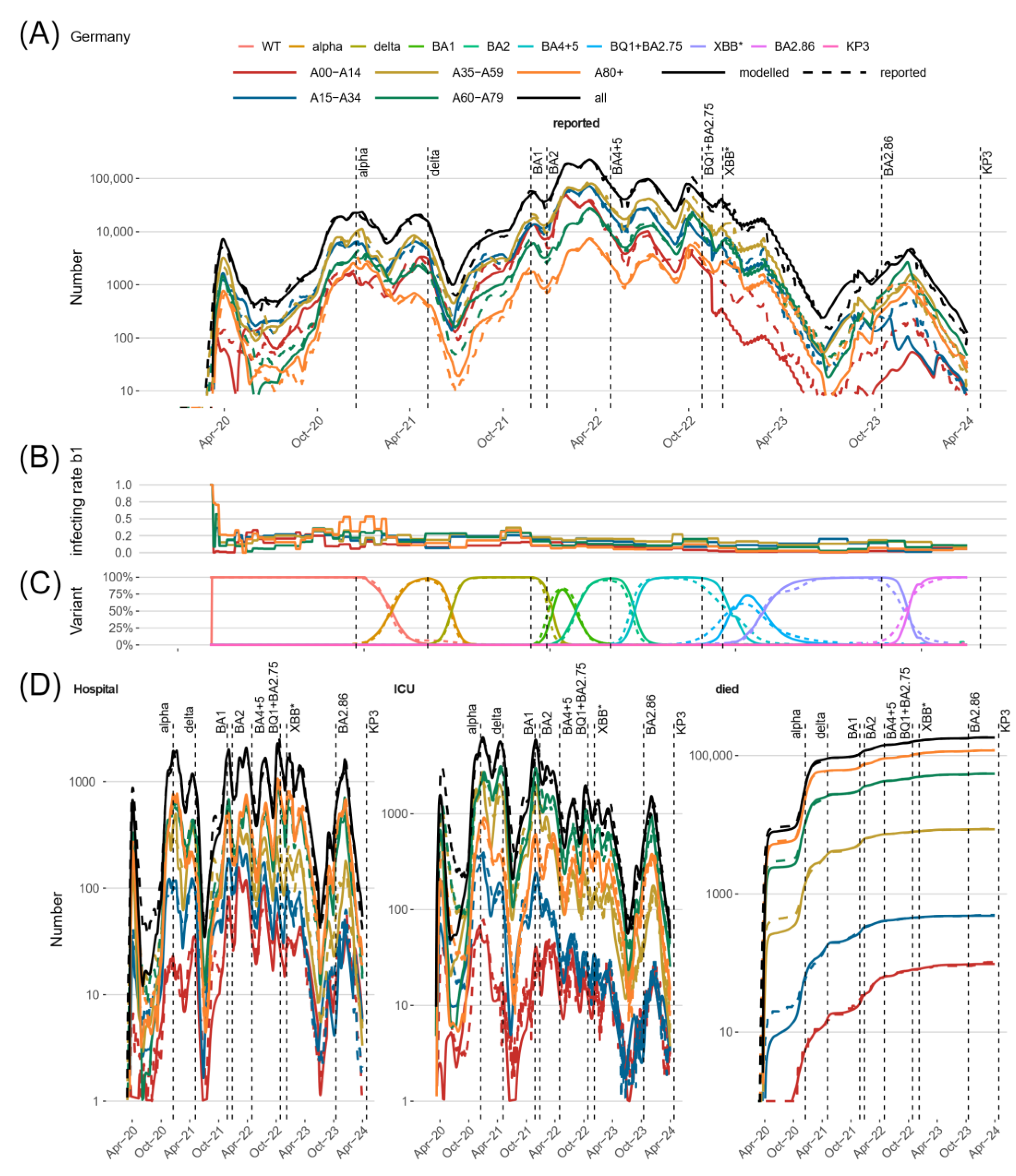

- Ten virus variants: WT (wild type); alpha; delta; and omicron BA1, BA2, BA5, and BA.2.75 with BQ.1, XBB, BA.2.86, and KP.3;

- Four immune statuses: Naïve due to absence of vaccinations or infections (S) or shortly after first vaccination (Vac0), highly protected by either recent vaccination (Vac1) or recovery from a recent infection (R1), moderately protected (Vac2, R2), and weakly protected (Vac3, R3), see Table 1.

- Infected compartments are those carrying a specific virus variant. This applies to the compartments E, I, H, and C;

- The latent state E comprises infected but non-contagious subjects. This is the transient state between becoming infected and becoming contagious;

- The infected state I is the only state assumed to be contagious and is divided into four sequential compartments. There is a single branching for the compartment I2, from which patients can proceed either to D (death compartment, representing deaths due to COVID-19) or to I3. Finally, the efflux of I4 enters R1, representing resolved disease courses;

- All sub-compartments of I contribute to new infections, depending on age, virus variant, and immune status of target subjects;

- The compartment I2 is considered the source of severe disease outcomes, comprising treatment at hospital wards H or ICU (C). These contributions are not modeled by fluxes but as counting respective bed occupancies;

- The compartment H represents disease states requiring hospital ward care. We assume that these patients are not infectious due to isolation. The compartment is divided into three sub-compartments, H1, H2, and H3, to allow comparisons with data on hospital ward bed occupancies. Rhosp counts resolved disease courses after hospital ward station care;

- The compartment C represents critical disease states requiring intensive care. Again, we assume that these patients are not infectious due to isolation. In analogy to the compartment of hospital ward treatment, this compartment is also divided into three sub-compartments to mimic disease courses, allowing for a comparison of the compartment with data of ICU bed occupancies. Ricu counts resolved disease courses after critical state to model cumulative data.

2.2.1. Input Layer

2.2.2. Output Layer, Data, and Parameter Fitting

2.2.3. Parametrization Approach

2.2.4. Implementation

3. Results

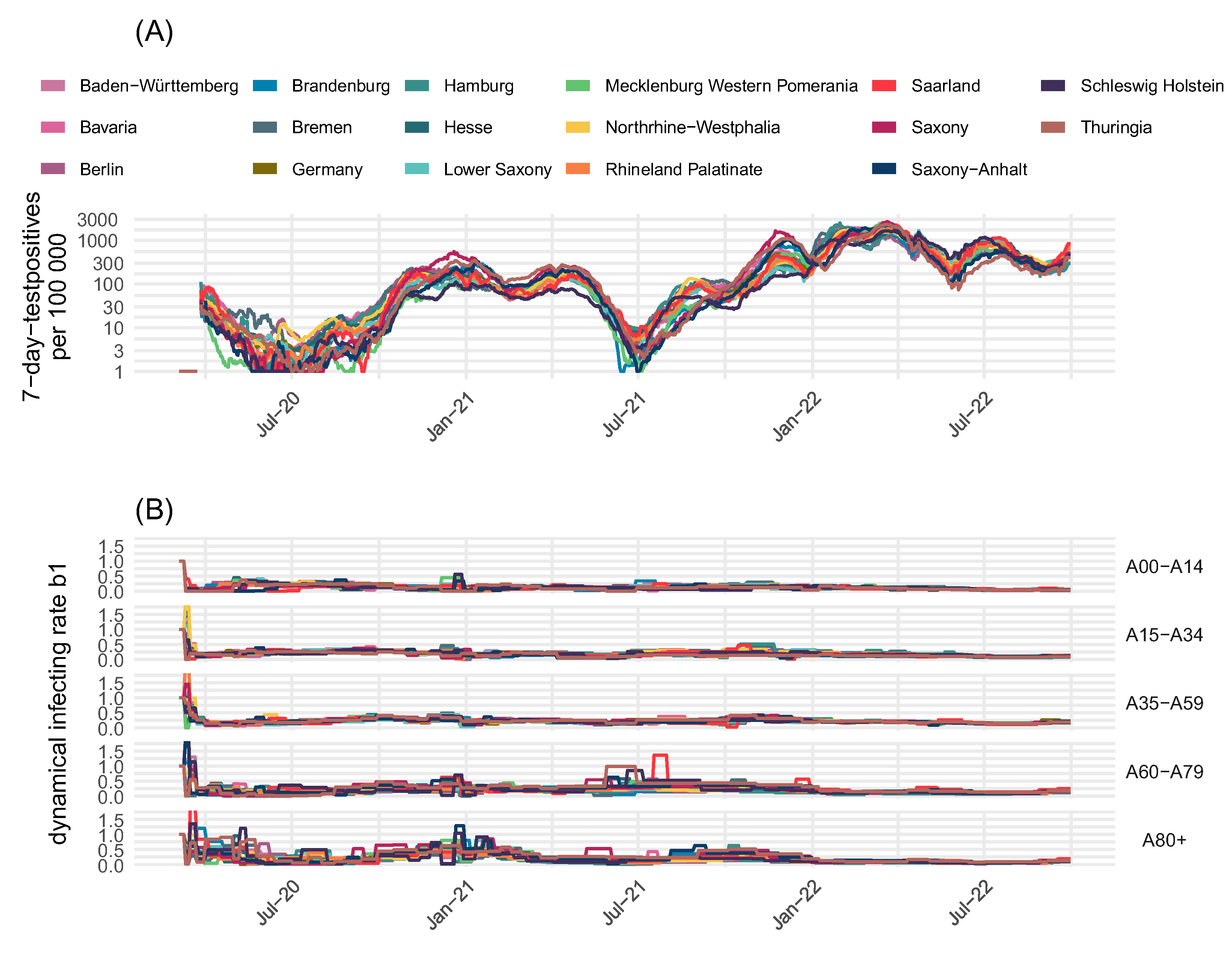

3.1. Parameter Fitting and Identifiability

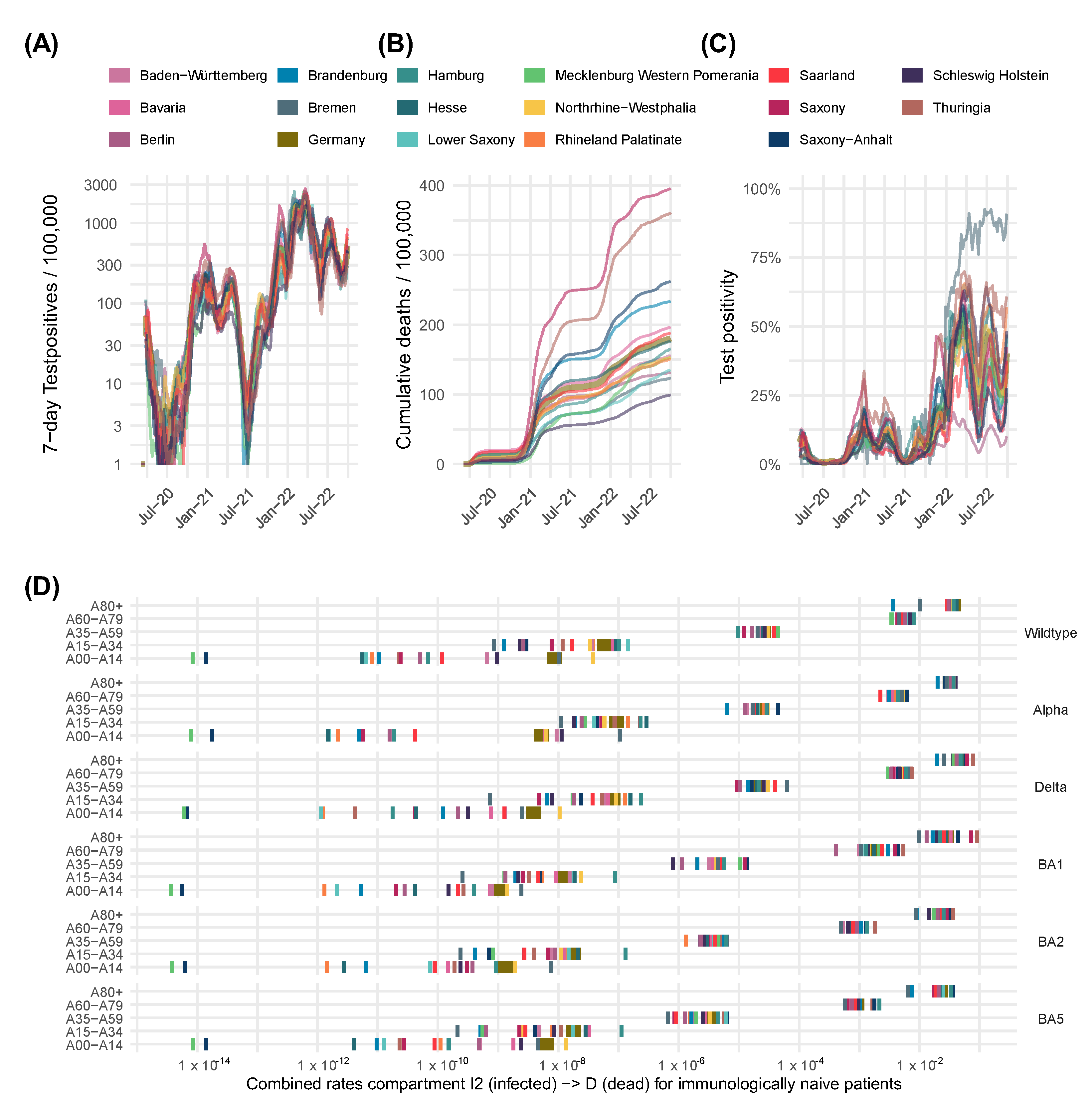

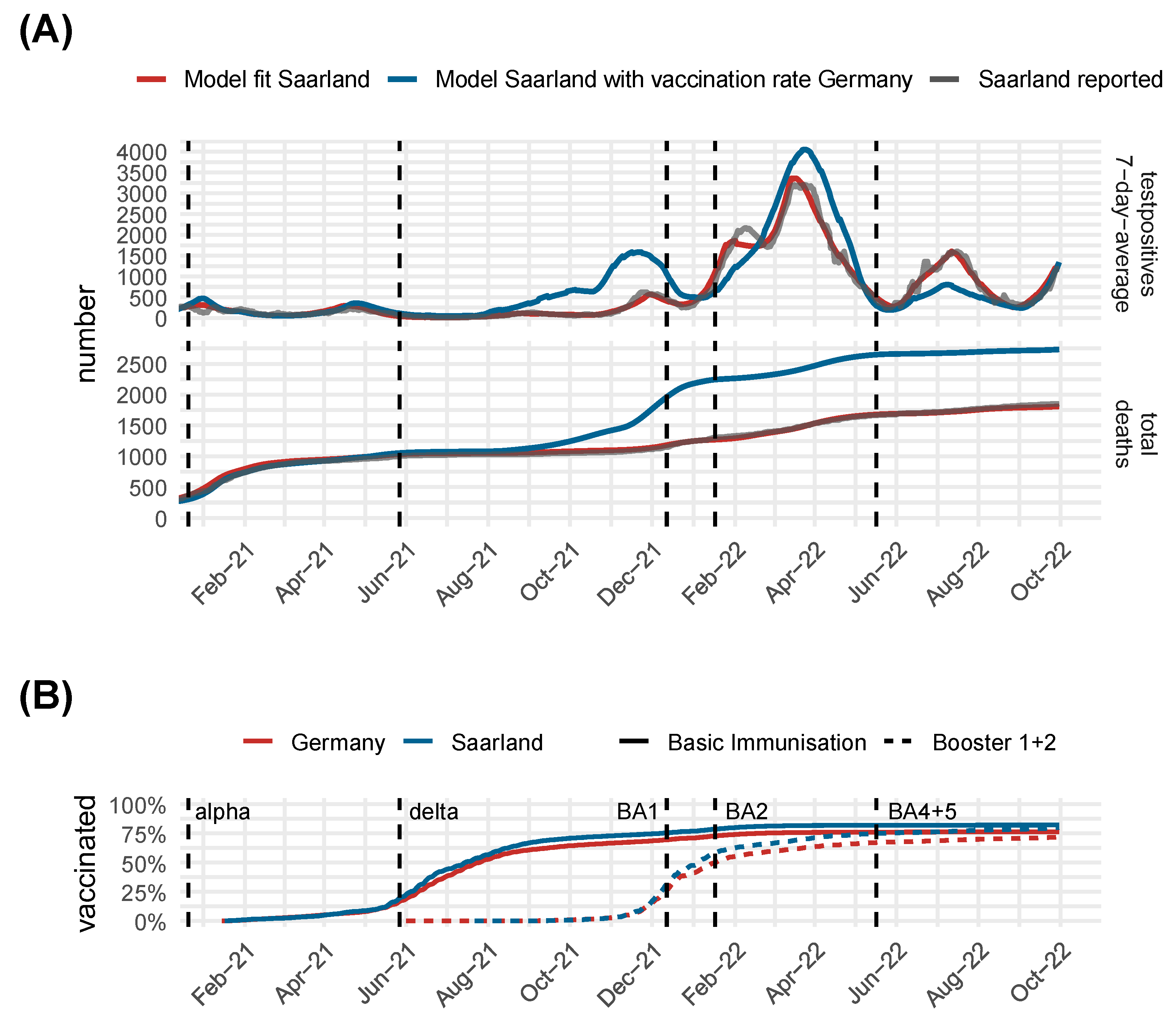

3.2. Comparison of Model Predictions and Observed Data for Germany and Its Federal States

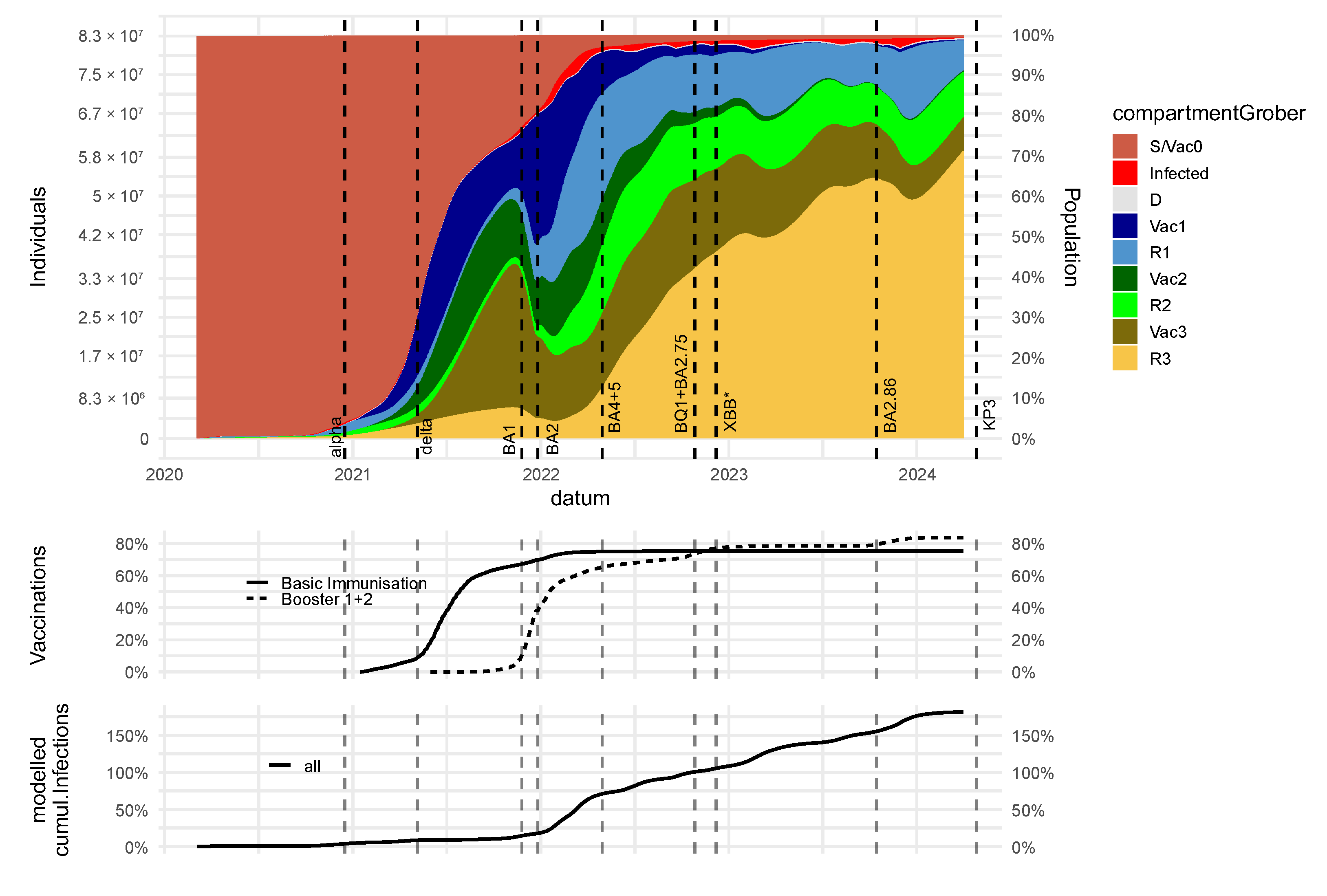

3.3. Dynamics of Immune States and Their Impact on Severe Disease Courses

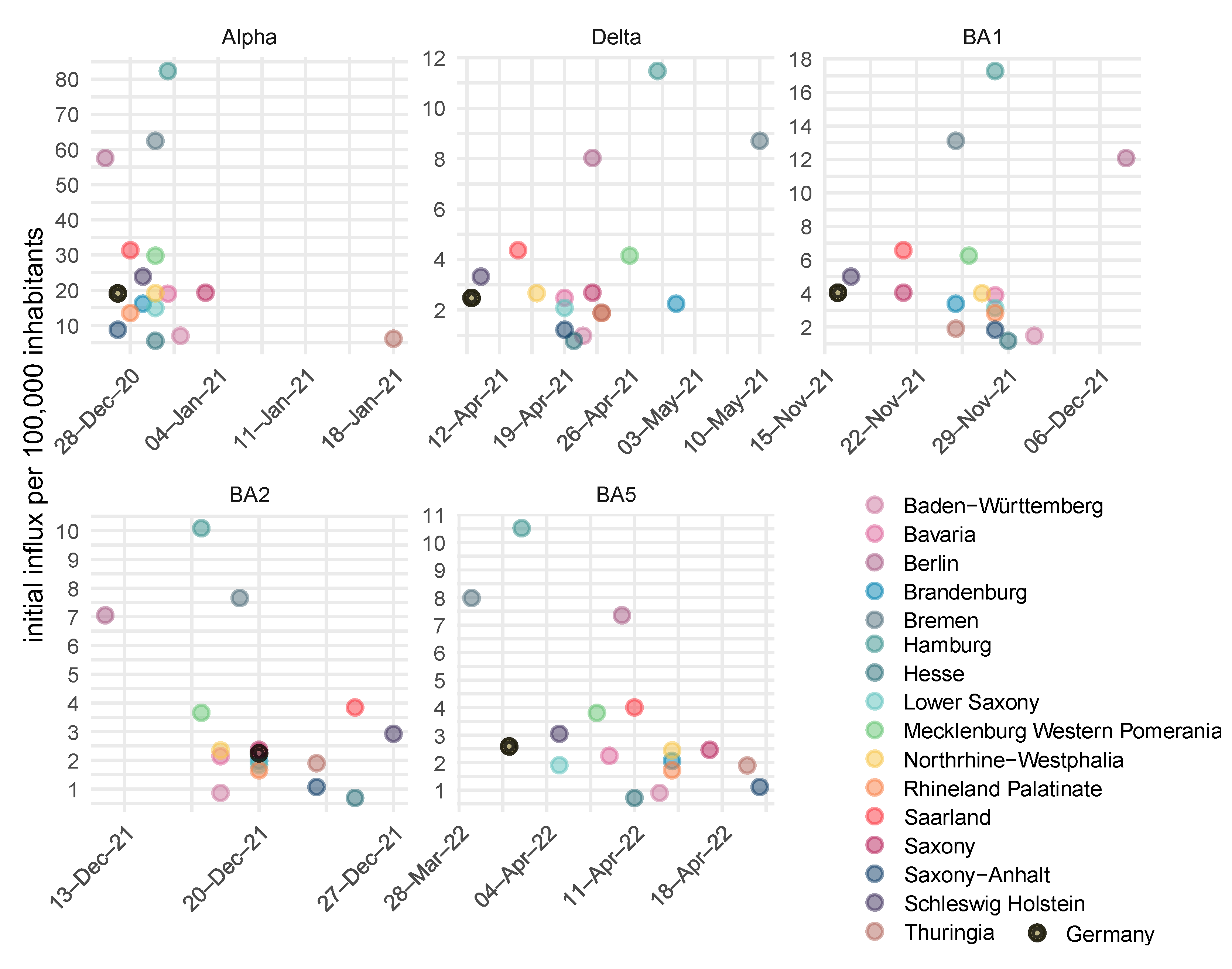

3.4. The SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic in Germany Exhibited Strong Regional Heterogeneity

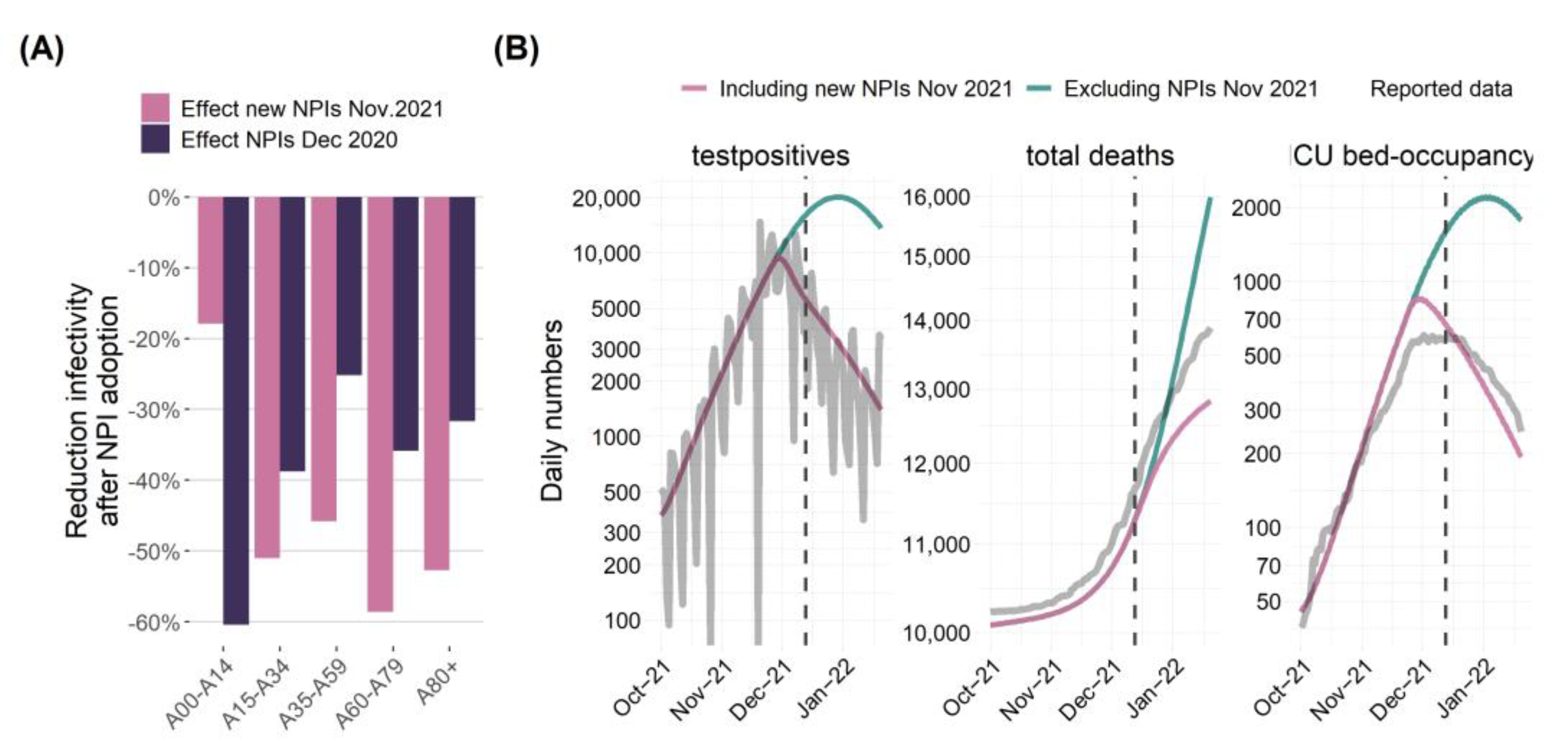

3.5. Validated Model Predictions

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A.S. | Andreas Schuppert |

| DIVI | Deutsche Interdisziplinäre Vereinigung für Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin e.V. |

| H.K. | Holger Kirsten |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IO-NLDS | Non-linear dynamical systems |

| M.S. | Markus Scholz |

| NPI | Non-pharmaceutical interventions |

| RKI | Robert Koch Institute |

| SECIR | Susceptible, exposed, cases, infectious, and recovered |

| Y.K. | Yuri Kheifetz |

References

- Tang, J.; Vinayavekhin, S.; Weeramongkolkul, M.; Suksanon, C.; Pattarapremcharoen, K.; Thiwathittayanuphap, S.; Leelawat, N. Agent-Based Simulation and Modeling of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Bibliometric Analysis. JDR 2022, 17, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharski, A.J.; Klepac, P.; Conlan, A.J.K.; Kissler, S.M.; Tang, M.L.; Fry, H.; Gog, J.R.; Edmunds, W.J.; Emery, J.C.; Medley, G.; et al. Effectiveness of isolation, testing, contact tracing, and physical distancing on reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in different settings: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quilty, B.J.; Clifford, S.; Hellewell, J.; Russell, T.W.; Kucharski, A.J.; Flasche, S.; Edmunds, W.J.; Atkins, K.E.; Foss, A.M.; Waterlow, N.R.; et al. Quarantine and testing strategies in contact tracing for SARS-CoV-2: A modelling study. Lancet Public Health 2021, 6, e175–e183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, I.; Chen, F.; Gandomi, A.H. A review on COVID-19 forecasting models. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 35, 23671–23681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flaxman, S.; Mishra, S.; Gandy, A.; Unwin, H.J.T.; Mellan, T.A.; Coupland, H.; Whittaker, C.; Zhu, H.; Berah, T.; Eaton, J.W.; et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature 2020, 584, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ram, V.; Schaposnik, L.P. A modified age-structured SIR model for COVID-19 type viruses. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, I.; Mondal, A.; Antonopoulos, C.G. A SIR model assumption for the spread of COVID-19 in different communities. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 139, 110057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, L.; Duan, M.; Shi, J.; Hong, J.; Chang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Compartmental structures used in modeling COVID-19: A scoping review. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2022, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burch, E.; Khan, S.; Stone, J.; Asgharzadeh, A.; Dawe, J.; Ward, Z.; Brooks-Pollock, E.; Christensen, H. Early mathematical models of COVID-19 vaccination in high-income countries: A systematic review. Public Health 2024, 236, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodiah, I.; Vanella, P.; Kuhlmann, A.; Jaeger, V.K.; Harries, M.; Krause, G.; Karch, A.; Bock, W.; Lange, B. Age-specific contribution of contacts to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Germany. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 38, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koslow, W.; Kühn, M.J.; Binder, S.; Klitz, M.; Abele, D.; Basermann, A.; Meyer-Hermann, M.; Struchiner, C.J. Appropriate relaxation of non-pharmaceutical interventions minimizes the risk of a resurgence in SARS-CoV-2 infections in spite of the Delta variant. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kheifetz, Y.; Kirsten, H.; Scholz, M. On the Parametrization of Epidemiologic Models—Lessons from Modelling COVID-19 Epidemic. Viruses 2022, 14, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.E. Overcoming Reporting Delays Is Critical to Timely Epidemic Monitoring: The Case of COVID-19 in New York City. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, S.; Oh, D.-Y.; Staat, D.; Stern, D.; Albrecht, S.; Wilrich, N.; Zacher, B.; Mielke, M.; Rexroth, U.; Hamouda, O.; et al. Erfassung der SARS-CoV-2-Testzahlen in Deutschland (Stand 2.12.2020); Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Georgatzis, K.; Williams, C.K.I.; Hawthorne, C. Input-Output Non-Linear Dynamical Systems applied to Physiological Condition Monitoring. In Proceedings of the 1st Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference 2016 (PMLR), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 19–20 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Khailaie, S.; Mitra, T.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Schips, M.; Mascheroni, P.; Vanella, P.; Lange, B.; Binder, S.C.; Meyer-Hermann, M. Development of the reproduction number from coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 case data in Germany and implications for political measures. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friberg, L.E.; Henningsson, A.; Maas, H.; Nguyen, L.; Karlsson, M.O. Model of chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression with parameter consistency across drugs. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002, 20, 4713–4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehning, J.; Zierenberg, J.; Spitzner, F.P.; Wibral, M.; Neto, J.P.; Wilczek, M.; Priesemann, V. Inferring change points in the spread of COVID-19 reveals the effectiveness of interventions. Science 2020, 369, eabb9789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert-Koch Institut. (Ed.) COVID-19 Hospitalisierungen in Deutschland. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/robert-koch-institut/COVID-19-Hospitalisierungen_in_Deutschland (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- DIVI. Tagesreport-Archiv. 2020. Available online: https://www.intensivregister.de/#/index (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Robert Koch Institute. Bericht zu Virusvarianten von SARS-CoV-2 in Deutschland, Insbesondere zur Variant of Concern (VOC) B.1.1.7. Updated 3 March 2021. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/DESH/Bericht_VOC_2021-03-03.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Robert Koch-Institut. SARS-CoV-2 Sequenzdaten aus Deutschland; Zenodo: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kheifetz, Y.; Scholz, M. Modeling individual time courses of thrombopoiesis during multi-cyclic chemotherapy. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yann, L.; Boser, B.; Denker, J.S.; Henderson, D.; Howard, R.E.; Hubbard, W.E.; Jackel, L.D.; Touretzky, D.S. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Hooke, R.; Jeeves, T.A. “Direct Search” Solution of Numerical and Statistical Problems. J. ACM 1961, 8, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutz, C.; Raue, A.; Kaschek, D.; Timmer, J. Profile likelihood in systems biology. FEBS J. 2013, 280, 2564–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 government Response Tracker. Oxford, Great Britain 2020–2022. Updated March 2023. Available online: https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/covid-19-government-response-tracker (accessed on 18 March 2023).

- Bracher, J.; Wolffram, D.; Deuschel, J.; Görgen, K.; Ketterer, J.L.; Ullrich, A.; Abbott, S.; Barbarossa, M.V.; Bertsimas, D.; Bhatia, S.; et al. A pre-registered short-term forecasting study of COVID-19 in Germany and Poland during the second wave. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mossong, J.; Hens, N.; Jit, M.; Beutels, P.; Auranen, K.; Mikolajczyk, R.; Massari, M.; Salmaso, S.; Tomba, G.S.; Wallinga, J.; et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Der Heiden, M.; Buchholz, U. Modellierung von Beispielszenarien der SARS-CoV-2-Ausbreitung und Schwere in Deutschland; Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nishiura, H.; Linton, N.M.; Akhmetzhanov, A.R. Serial interval of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infections. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 93, 284–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tindale, L.C.; E Stockdale, J.; Coombe, M.; Garlock, E.S.; Lau, W.Y.V.; Saraswat, M.; Zhang, L.; Chen, D.; Wallinga, J.; Colijn, C. Evidence for transmission of COVID-19 prior to symptom onset. eLife 2020, 9, e57149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhmer, M.M.; Buchholz, U.; Corman, V.M.; Hoch, M.; Katz, K.; Marosevic, D.V.; Böhm, S.; Woudenberg, T.; Ackermann, N.; Konrad, R.; et al. Investigation of a COVID-19 outbreak in Germany resulting from a single travel-associated primary case: A case series. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganyani, T.; Kremer, C.; Chen, D.; Torneri, A.; Faes, C.; Wallinga, J.; Hens, N. Estimating the generation interval for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) based on symptom onset data, March 2020. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 2000257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanche, S.; Lin, Y.T.; Xu, C.; Romero-Severson, E.; Hengartner, N.; Ke, R. High Contagiousness and Rapid Spread of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 National Emergency Response Center, Epidemiology and Case Management Team, Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease-19: The First 7,755 Cases in the Republic of Korea. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2020, 11, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuppert, A.; Theisen, S.; Fränkel, P.; Weber-Carstens, S.; Karagiannidis, C. Bundesweites Belastungsmodell für Intensivstationen durch COVID-19. Med. Klin. Intensivmed. Notfmed. 2021, 117, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolksdorf, K.; Buda, S.; Schuler, E.; Wieler, L.H.; Haas, W. Eine höhere Letalität und lange Beatmungsdauer unterscheiden COVID-19 von schwer verlaufenden Atemwegsinfektionen in Grippewellen. Epidemiol. Bull. 2020, 41, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannidis, C.; Mostert, C.; Hentschker, C.; Voshaar, T.; Malzahn, J.; Schillinger, G.; Klauber, J.; Janssens, U.; Marx, G.; Weber-Carstens, S.; et al. Case characteristics, resource use, and outcomes of 10 021 patients with COVID-19 admitted to 920 German hospitals: An observational study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verity, R.; Okell, L.C.; Dorigatti, I.; Winskill, P.; Whittaker, C.; Imai, N.; Cuomo-Dannenburg, G.; Thompson, H.; Walker, P.G.T.; Fu, H.; et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: A model-based analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 669–677, Erratum in Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, N.M.; Kobayashi, T.; Yang, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Akhmetzhanov, A.R.; Jung, S.-M.; Yuan, B.; Kinoshita, R.; Nishiura, H. Incubation Period and Other Epidemiological Characteristics of 2019 Novel Coronavirus Infections with Right Truncation: A Statistical Analysis of Publicly Available Case Data. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UK Health Security Agency (Ed.) COVID-19 Vaccine Surveillance Report. Week 14. 7 April 2022. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1067158/vaccine-surveillance-report-week-14.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- UK Public Health England (Ed.) COVID-19 Vaccine Surveillance Report. Week 19. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/986361/Vaccine_surveillance__report__week_19.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- UK Health Security Agency. Vaccine Surveillance Report, Week 26. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/998411/Vaccine_surveillance_report_-_week_26.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Altarawneh, H.N.; Chemaitelly, H.; Ayoub, H.H.; Hasan, M.R.; Coyle, P.; Yassine, H.M.; Al-Khatib, H.A.; Benslimane, F.M.; Al-Kanaani, Z.; Al-Kuwari, E.; et al. Protection of SARS-CoV-2 natural infection against reinfection with the Omicron BA.4 or BA.5 subvariants. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarawneh, H.N.; Chemaitelly, H.; Ayoub, H.; Tang, P.; Hasan, M.R.; Yassine, H.M.; Al-Khatib, H.A.; Smatti, M.K.; Coyle, P.; Al-Kanaani, Z.; et al. Effect of prior infection, vaccination, and hybrid immunity against symptomatic BA.1 and BA.2 Omicron infections and severe COVID-19 in Qatar. medRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemaitelly, H.; Ayoub, H.H.; Coyle, P.; Tang, P.; Yassine, H.M.; Al-Khatib, H.A.; Smatti, M.K.; Hasan, M.R.; Al-Kanaani, Z.; Al-Kuwari, E.; et al. Protection of Omicron sub-lineage infection against reinfection with another Omicron sub-lineage. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert Koch Institut (Ed.) SARS-CoV-2 Sequenzdaten aus Deutschland. Available online: https://robert-koch-institut.github.io/SARS-CoV-2-Sequenzdaten_aus_Deutschland/ (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Wu, Y.; Kang, L.; Guo, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Liang, W. Incubation Period of COVID-19 Caused by Unique SARS-CoV-2 Strains: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2228008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Pei, S.; Chen, B.; Song, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, W.; Shaman, J. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2). Science 2020, 368, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lord, J.M. The effect of ageing of the immune system on vaccination responses. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2013, 9, 1364–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Balfe, P.; Eyre, D.W.; Lumley, S.F.; O’dOnnell, D.; Warren, F.; Crook, D.W.; Jeffery, K.; Matthews, P.C.; Klerman, E.B.; et al. Time of Day of Vaccination Affects SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Responses in an Observational Study of Health Care Workers. J. Biol. Rhythm. 2022, 37, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altarawneh, H.N.; Chemaitelly, H.; Ayoub, H.H.; Tang, P.; Hasan, M.R.; Yassine, H.M.; Al-Khatib, H.A.; Smatti, M.K.; Coyle, P.; Al-Kanaani, Z.; et al. Effects of Previous Infection and Vaccination on Symptomatic Omicron Infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 387, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serologische Untersuchungen von Blutspenden auf Antikörper gegen SARS-CoV-2 (SeBluCo-Studie). 2021. Available online: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Projekte_RKI/SeBluCo_Zwischenbericht.html (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Schulze-Wundling, K.; Ottensmeyer, P.F.; Meyer-Schlinkmann, K.M.; Deckena, M.; Krüger, S.; Schlinkert, S.; Budde, A.; Münstermann, D.; Töpfner, N.; Petersmann, A.; et al. Immunity Against SARS-CoV-2 in the German Population. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2023, 120, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachtler, B.; Neuhauser, H.; Haller, S.; Grabka, M.M.; Zinn, S.; Schaade, L.; Hövener, C.; Hoebel, J. The Risk of Infection with SARS-CoV-2 Among Healthcare Workers During the Pandemic. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2021, 118, 842–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compartment | Risk of Infection | Immune Status (see Figure 2) | Risk of Severe Course of Disease (Hospital Ward H, ICU Requirement C, Death D) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S, Vac0 | highest | Naive | Highest risk for H, C, and D |

| Vac1, R1 | small | Protected | No risk for C and D and reduced risk for H (40% compared to S, Vac0) |

| Vac2, R2 | medium | ||

| Vac3, R3 | high | Waned | Medium risk for H, C, and D (40% compared to S, Vac0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kheifetz, Y.; Kirsten, H.; Schuppert, A.; Scholz, M. Modeling the Complete Dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic of Germany and Its Federal States Using Multiple Levels of Data. Viruses 2025, 17, 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070981

Kheifetz Y, Kirsten H, Schuppert A, Scholz M. Modeling the Complete Dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic of Germany and Its Federal States Using Multiple Levels of Data. Viruses. 2025; 17(7):981. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070981

Chicago/Turabian StyleKheifetz, Yuri, Holger Kirsten, Andreas Schuppert, and Markus Scholz. 2025. "Modeling the Complete Dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic of Germany and Its Federal States Using Multiple Levels of Data" Viruses 17, no. 7: 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070981

APA StyleKheifetz, Y., Kirsten, H., Schuppert, A., & Scholz, M. (2025). Modeling the Complete Dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic of Germany and Its Federal States Using Multiple Levels of Data. Viruses, 17(7), 981. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17070981