The Dual Role of A20 (TNFAIP3) in Viral Infection: A Context-Dependent Regulator of Immunity and Pathogenesis

Abstract

1. Introduction

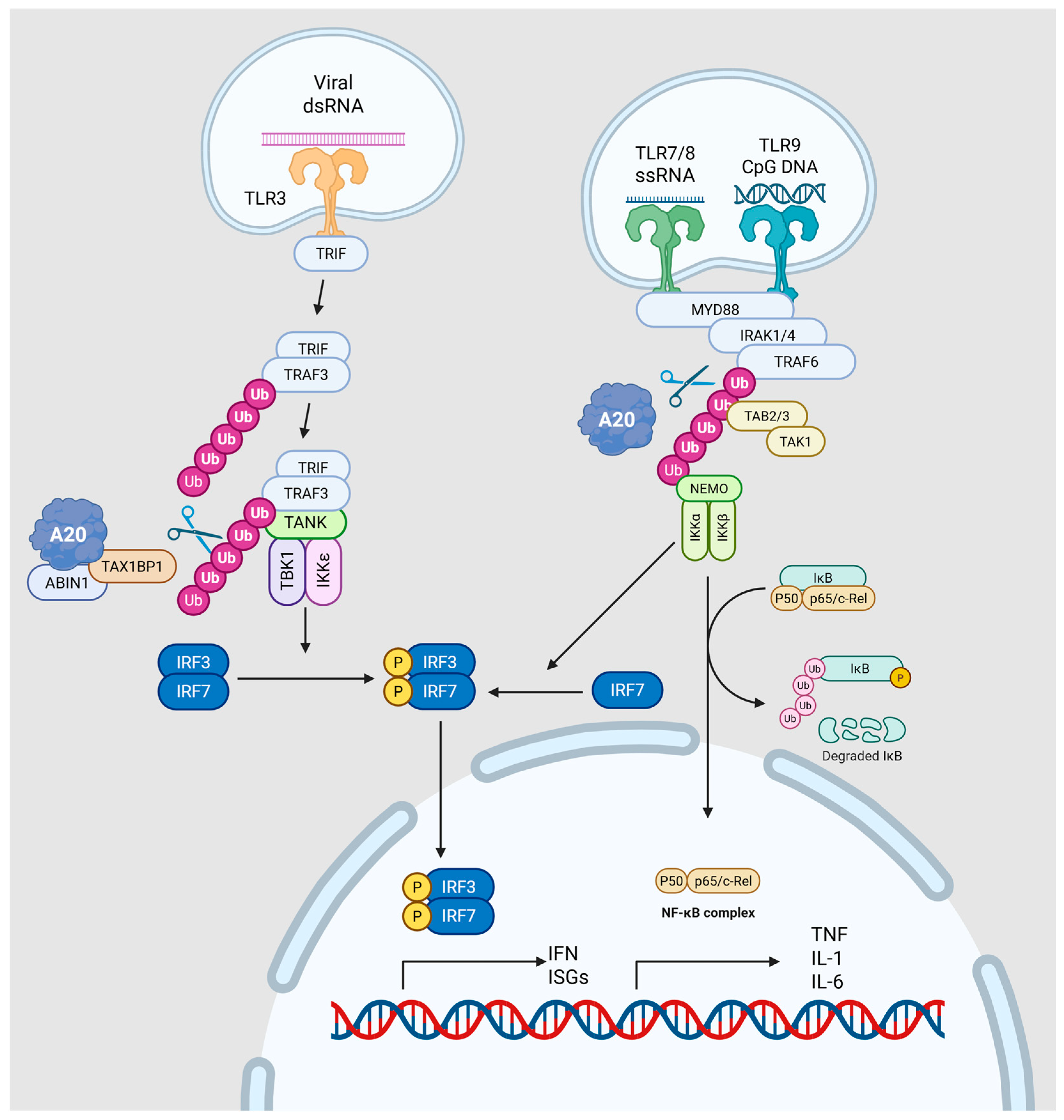

2. Molecular Mechanisms of A20 Regulation

2.1. Transcriptional Control of A20 Expression

2.2. Structural Organization and Catalytic Mechanisms

2.3. Functional Mechanisms in Cellular Signaling

2.4. Broader Biological Functions Beyond NF-κB

3. Proviral Effects of A20

3.1. Hepatitis C Virus

3.2. Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup A

3.3. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus

3.4. Sendai Virus

3.5. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus

3.6. Human Coronavirus 229E

3.7. Human Cytomegalovirus

3.8. Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus

3.9. Measles Virus

4. Antiviral Effects of A20

4.1. Poliovirus

4.2. Coxsackievirus B3

5. Dual Effects of A20

5.1. Zika Virus

5.2. Influenza A Virus

5.3. Hepatitis B Virus

5.4. Epstein–Barr Virus

5.5. Human T-Cell Leukemia Virus Type 1

6. Context-Dependent Effects of A20

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

7. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parvatiyar, K.; Barber, G.N.; Harhaj, E.W. TAX1BP1 and A20 Inhibit Antiviral Signaling by Targeting TBK1-IKKi Kinases*. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 14999–15009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Coope, H.; Grant, S.; Ma, A.; Ley, S.C.; Harhaj, E.W. ABIN1 Protein Cooperates with TAX1BP1 and A20 Proteins to Inhibit Antiviral Signaling*. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 36592–36602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstrepen, L.; Verhelst, K.; van Loo, G.; Carpentier, I.; Ley, S.C.; Beyaert, R. Expression, biological activities and mechanisms of action of A20 (TNFAIP3). Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 80, 2009–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyninck, K.; Beyaert, R. A20 inhibits NF-κB activation by dual ubiquitin-editing functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005, 30, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priem, D.; van Loo, G.; Bertrand, M.J.M. A20 and Cell Death-driven Inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2020, 41, 421–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungerbäck, J.; Belenki, D.; Jawad ul-Hassan, A.; Fredrikson, M.; Fransén, K.; Elander, N.; Verma, D.; Söderkvist, P. Genetic variation and alterations of genes involved in NFκB/TNFAIP3- and NLRP3-inflammasome signaling affect susceptibility and outcome of colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis 2012, 33, 2126–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nocturne, G.; Boudaoud, S.; Miceli-Richard, C.; Viengchareun, S.; Lazure, T.; Nititham, J.; Taylor, K.E.; Ma, A.; Busato, F.; Melki, J.; et al. Germline and somatic genetic variations of TNFAIP3 in lymphoma complicating primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Blood 2013, 122, 4068–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; He, L.; Li, R.; Li, J.; Zhao, Q.; Shao, B. A20 as a Potential Therapeutic Target for COVID-19. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2025, 13, e70127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-C.; Chung, J.Y.; Lamothe, B.; Rajashankar, K.; Lu, M.; Lo, Y.-C.; Lam, A.Y.; Darnay, B.G.; Wu, H. Molecular Basis for the Unique Deubiquitinating Activity of the NF-κB Inhibitor A20. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 376, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; He, X.; Huang, N.; Yu, J.; Shao, B. A20: A master regulator of arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2020, 22, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Malynn, B.A. A20: Linking a complex regulator of ubiquitylation to immunity and human disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 12, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komander, D.; Barford, D. Structure of the A20 OTU domain and mechanistic insights into deubiquitination. Biochem. J. 2008, 409, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shembade, N.; Parvatiyar, K.; Harhaj, N.S.; Harhaj, E.W. The ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20 requires RNF11 to downregulate NF-kappaB signalling. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millman, A.J.; Nelson, N.P.; Vellozzi, C. Hepatitis C: Review of the Epidemiology, Clinical Care, and Continued Challenges in the Direct Acting Antiviral Era. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 2017, 4, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrents de la Peña, A.; Sliepen, K.; Eshun-Wilson, L.; Newby, M.L.; Allen, J.D.; Zon, I.; Koekkoek, S.; Chumbe, A.; Crispin, M.; Schinkel, J.; et al. Structure of the hepatitis C virus E1E2 glycoprotein complex. Science 2022, 378, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chan, S.T.; Kim, J.Y.; Ou, J.J. Hepatitis C Virus Induces the Ubiquitin-Editing Enzyme A20 via Depletion of the Transcription Factor Upstream Stimulatory Factor 1 To Support Its Replication. mBio 2019, 10, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, B.; He, Y.; Guo, Y.; Jia, Z. Up-regulation of A20/ABIN1 contributes to inefficient M1 macrophage polarization during Hepatitis C virus infection. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, J.; Lian, J.; Hao, C.; Moorman, J.P.; et al. Role of A20 in interferon-α-mediated functional restoration of myeloid dendritic cells in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Immunology 2014, 143, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Li, J.; Chang, Y.-F.; Lin, W. Avian Leucosis Virus-Host Interaction: The Involvement of Host Factors in Viral Replication. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 907287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Fang, C.; Liu, J.; Liang, X.; Yang, Y. A20 Enhances the Expression of the Proto-Oncogene C-Myc by Downregulating TRAF6 Ubiquitination after ALV-A Infection. Viruses 2022, 14, 2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Fang, C.; Liu, J.; Liang, X.; Yang, Y. Enhanced pathogenicity by up-regulation of A20 after avian leukemia subgroup a virus infection. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 1031480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.B.; Meyers, G.; Bukh, J.; Gould, E.A.; Monath, T.; Scott Muerhoff, A.; Pletnev, A.; Rico-Hesse, R.; Stapleton, J.T.; Simmonds, P.; et al. Proposed revision to the taxonomy of the genus Pestivirus, family Flaviviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2106–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Romero, N.; Arias, C.F.; Verdugo-Rodríguez, A.; López, S.; Valenzuela-Moreno, L.F.; Cedillo-Peláez, C.; Basurto-Alcántara, F.J. Immune protection induced by E2 recombinant glycoprotein of bovine viral diarrhea virus in a murine model. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1168846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, M.; Canales, N.; Maldonado, N.; Otth, C.; Fredericksen, F.; Garcés, P.; Stepke, C.; Arriagada, V.; Olavarría, V.H. Bovine A20 gene overexpression during bovine viral diarrhea virus-1 infection blocks NF-κB pathway in MDBK cells. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2017, 77, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericksen, F.; Villalba, M.; Olavarría, V.H. Characterization of bovine A20 gene: Expression mediated by NF-κB pathway in MDBK cells infected with bovine viral diarrhea virus-1. Gene 2016, 581, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loney, C.; Mottet-Osman, G.; Roux, L.; Bhella, D. Paramyxovirus Ultrastructure and Genome Packaging: Cryo-Electron Tomography of Sendai Virus. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 8191–8197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokata, K.; Nishiyama, Y.; Ito, Y.; Kimura, Y.; Nagata, I. Pathogenesis of Sendai virus infection in the central nervous system of mice. Infect. Immun. 1976, 13, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, R.; Morita, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Koide, N.; Komatsu, T. Sendai virus C protein affects macrophage function, which plays a critical role in modulating disease severity during Sendai virus infection in mice. Microbiol. Immunol. 2022, 66, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irie, T.; Nagata, N.; Yoshida, T.; Sakaguchi, T. Paramyxovirus Sendai virus C proteins are essential for maintenance of negative-sense RNA genome in virus particles. Virology 2008, 374, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensson, K.; Orvell, C.; Leestma, J.; Norrby, E. Sendai virus infection in the brains of mice: Distribution of viral antigens studied with monoclonal antibodies. J. Infect. Dis. 1983, 147, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Li, L.; Han, K.J.; Zhai, Z.; Shu, H.B. A20 is a potent inhibitor of TLR3- and Sendai virus-induced activation of NF-kappaB and ISRE and IFN-beta promoter. FEBS Lett. 2004, 576, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Yang, L.; Nakhaei, P.; Sun, Q.; Sharif-Askari, E.; Julkunen, I.; Hiscott, J. Negative regulation of the retinoic acid-inducible gene I-induced antiviral state by the ubiquitin-editing protein A20. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 2095–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.M.; Okesanya, O.J.; Ukoaka, B.M.; Ibrahim, A.M.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E., 3rd. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus: Insights into Pathogenesis, Immune Evasion, and Technological Innovations in Oncolytic and Vaccine Development. Viruses 2024, 16, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Cao, W.; Salawudeen, A.; Zhu, W.; Emeterio, K.; Safronetz, D.; Banadyga, L. Vesicular Stomatitis Virus: From Agricultural Pathogen to Vaccine Vector. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mire, C.E.; White, J.M.; Whitt, M.A. A Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Matrix Protein and Nucleocapsid Trafficking during Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Uncoating. PLOS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1000994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshiumi, H.; Miyashita, M.; Inoue, N.; Okabe, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Seya, T. The Ubiquitin Ligase Riplet Is Essential for RIG-I-Dependent Innate Immune Responses to RNA Virus Infection. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 8, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, H.; Takeuchi, O.; Sato, S.; Yoneyama, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Matsui, K.; Uematsu, S.; Jung, A.; Kawai, T.; Ishii, K.J.; et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature 2006, 441, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Shi, Y.; Ding, W.; Niu, T.; Sun, L.; Tan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shi, J.; Xiong, Q.; Huang, X.; et al. Cryo-EM analysis of the HCoV-229E spike glycoprotein reveals dynamic prefusion conformational changes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siragam, V.; Maltseva, M.; Castonguay, N.; Galipeau, Y.; Srinivasan Mrudhula, M.; Soto Justino, H.; Dankar, S.; Langlois, M.-A. Seasonal human coronaviruses OC43, 229E, and NL63 induce cell surface modulation of entry receptors and display host cell-specific viral replication kinetics. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e04220–e04223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-X.; Chien, Y.-C.; Hsu, M.-F.; Khoo, K.-H.; Hsu, S.-T.D. Molecular basis of host recognition of human coronavirus 229E. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poppe, M.; Wittig, S.; Jurida, L.; Bartkuhn, M.; Wilhelm, J.; Müller, H.; Beuerlein, K.; Karl, N.; Bhuju, S.; Ziebuhr, J.; et al. The NF-κB-dependent and -independent transcriptome and chromatin landscapes of human coronavirus 229E-infected cells. PLOS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijmons, S.; Van Ranst, M.; Maes, P. Genomic and functional characteristics of human cytomegalovirus revealed by next-generation sequencing. Viruses 2014, 6, 1049–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Li, X. Human cytomegalovirus: Pathogenesis, prevention, and treatment. Mol. Biomed. 2024, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.Y.; Kim, Y.-E.; Kwon, K.M.; Han, T.-H.; Ahn, J.-H. Biphasic regulation of A20 gene expression during human cytomegalovirus infection. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Chen, C.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J. Global progress in clinical research on human respiratory syncytial virus vaccines. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1457703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñana, M.; González-Sánchez, A.; Andrés, C.; Vila, J.; Creus-Costa, A.; Prats-Méndez, I.; Arnedo-Muñoz, M.; Saubi, N.; Esperalba, J.; Rando, A.; et al. Genomic evolution of human respiratory syncytial virus during a decade (2013–2023): Bridging the path to monoclonal antibody surveillance. J. Infect. 2024, 88, 106153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Vicente, M.; González-Sanz, R.; Cuesta, I.; Monzón, S.; Resino, S.; Martínez, I. Downregulation of A20 Expression Increases the Immune Response and Apoptosis and Reduces Virus Production in Cells Infected by the Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Vaccines 2020, 8, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Descamps, D.; Peres de Oliveira, A.; Gonnin, L.; Madrières, S.; Fix, J.; Drajac, C.; Marquant, Q.; Bouguyon, E.; Pietralunga, V.; Iha, H.; et al. Depletion of TAX1BP1 Amplifies Innate Immune Responses during Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2021, 95, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misin, A.; Antonello, R.M.; Di Bella, S.; Campisciano, G.; Zanotta, N.; Giacobbe, D.R.; Comar, M.; Luzzati, R. Measles: An Overview of a Re-Emerging Disease in Children and Immunocompromised Patients. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuhara, H.; Mwaba, M.H.; Maenaka, K. Structural characteristics of measles virus entry. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2020, 41, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, W.J.; Griffin, D.E. What’s going on with measles? J. Virol. 2024, 98, e00758-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz Katharina, S.; Handrejk, K.; Liepina, L.; Bauer, L.; Haas Griffin, D.; van Puijfelik, F.; Veldhuis Kroeze Edwin, J.B.; Riekstina, M.; Strautmanis, J.; Cao, H.; et al. Functional properties of measles virus proteins derived from a subacute sclerosing panencephalitis patient who received repeated remdesivir treatments. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e01874-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, S.; Okabayashi, T.; Yokosawa, N.; Fujii, N. Measles virus P protein suppresses Toll-like receptor signal through up-regulation of ubiquitin-modifying enzyme A20. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños-Martínez, O.C.; Strasser, R. Plant-made poliovirus vaccines—Safe alternatives for global vaccination. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1046346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogle, J.M. Poliovirus cell entry: Common structural themes in viral cell entry pathways. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2002, 56, 677–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doukas, T.; Sarnow, P. Escape from transcriptional shutoff during poliovirus infection: NF-κB-responsive genes IκBa and A20. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 10101–10108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Chen, S.; Sun, X.; Zhou, C. Immune mechanisms of group B coxsackievirus induced viral myocarditis. Virulence 2023, 14, 2180951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, R.S.; Tavares, F.N.; Sousa, I.P. Global landscape of coxsackieviruses in human health. Virus Res. 2024, 344, 199367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Xie, X. A20 (TNFAIP3) alleviates viral myocarditis through ADAR1/miR-1a-3p-dependent regulation. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2022, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishburn, A.T.; Florio, C.J.; Klaessens, T.N.; Prince, B.; Adia, N.A.B.; Lopez, N.J.; Beesabathuni, N.S.; Becker, S.S.; Cherkashchenko, L.; Haggard Arcé, S.T.; et al. Microcephaly protein ANKLE2 promotes Zika virus replication. mBio 2024, 16, e0268324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, C.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, C.; Qin, Y.; Chen, M. Zika virus inhibits cell death by inhibiting the expression of NLRP3 and A20. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e01980-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, A.F.Y. Prospects for a sequence-based taxonomy of influenza A virus subtypes. Virus Evol. 2024, 10, veae064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Pan, M.; Guo, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Q.C.; Deng, T.; Wang, J. Mapping of the influenza A virus genome RNA structure and interactions reveals essential elements of viral replication. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Shi, N.; Song, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Duan, M. Induction of the cellular microRNA-29c by influenza virus contributes to virus-mediated apoptosis through repression of antiapoptotic factors BCL2L2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 425, 662–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, C.; Sun, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M.; Guan, Z.; Duan, M. Induction of the cellular miR-29c by influenza virus inhibits the innate immune response through protection of A20 mRNA. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Sun, X.; Shi, N.; Zhang, M.; Guan, Z.; Duan, M. Influenza a virus NS1 protein induced A20 contributes to viral replication by suppressing interferon-induced antiviral response. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 482, 1107–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maelfait, J.; Roose, K.; Vereecke, L.; Mc Guire, C.; Sze, M.; Schuijs, M.J.; Willart, M.; Itati Ibañez, L.; Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N.; et al. A20 Deficiency in Lung Epithelial Cells Protects against Influenza A Virus Infection. PLOS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maelfait, J.; Roose, K.; Bogaert, P.; Sze, M.; Saelens, X.; Pasparakis, M.; Carpentier, I.; van Loo, G.; Beyaert, R. A20 (Tnfaip3) Deficiency in Myeloid Cells Protects against Influenza A Virus Infection. PLOS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Hsu, A.C.-Y.; Zuo, X.; Guo, X.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, S.; Ouyang, Z.; Wang, F. Chronic exposure to low-level lipopolysaccharide dampens influenza-mediated inflammatory response via A20 and PPAR network. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1119473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, L.; Yin, Q.; Shen, T. A review of epidemiology and clinical relevance of Hepatitis B virus genotypes and subgenotypes. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2023, 47, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.L.; Huang, A.L. Classifying hepatitis B therapies with insights from covalently closed circular DNA dynamics. Virol. Sin. 2024, 39, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Huang, C.; Li, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhao, K.; Fang, Z.; Chen, J. Hepatitis B surface antigen impairs TLR4 signaling by upregulating A20 expression in monocytes. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e00909-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, P.; Sang, J.; Li, F.; Deng, H.; Lv, Y.; Han, Q.; Liu, Z. Association of the tandem polymorphisms (rs148314165, rs200820567) in TNFAIP3 with chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Chinese Han population. Virol. J. 2017, 14, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhuang, N.; Zhao, D.; He, J.; Shi, L. Hepatitis B Virus X Protein Sensitizes TRAIL-Induced Hepatocyte Apoptosis by Inhibiting the E3 Ubiquitin Ligase A20. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.Y.; Fan, Y.C.; Wang, N.; Xia, H.H.; Xiao, X.Y.; Wang, K. Increased A20 mRNA Level in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells is Associated With Immune Phases of Patients With Chronic Hepatitis B. Medicine 2015, 94, e2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.-C.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Wang, N.; Xiao, X.-Y.; Wang, K. Altered expression of A20 gene in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is associated with the progression of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 68821–68832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.-C.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Wang, N.; Xiao, X.-Y.; Wang, K. Up-regulation of A20 gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is associated with acute-on-chronic hepatitis B liver failure. J. Viral Hepat. 2016, 23, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, I.Y.; Giulino-Roth, L. Targeting latent viral infection in EBV-associated lymphomas. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1342455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.d.M.; Alves, C.E.d.C.; Pontes, G.S. Epstein-Barr virus: The mastermind of immune chaos. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1297994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaadawe, M.; Radman, B.A.; Long, J.; Alsaadawi, M.; Fang, W.; Lyu, X. Epstein Barr virus: A cellular hijacker in cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laherty, C.D.; Hu, H.M.; Opipari, A.W.; Wang, F.; Dixit, V.M. The Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 gene product induces A20 zinc finger protein expression by activating nuclear factor kappa B. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 24157–24160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fries, K.L.; Miller, W.E.; Raab-Traub, N. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 blocks p53-mediated apoptosis through the induction of the A20 gene. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 8653–8659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, S.; Pagano, J.S. The A20 deubiquitinase activity negatively regulates LMP1 activation of IRF7. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 6130–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, M.; Sato, Y.; Takata, K.; Nomoto, J.; Nakamura, S.; Ohshima, K.; Takeuchi, T.; Orita, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yoshino, T. A20 (TNFAIP3) deletion in Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders/lymphomas. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulino, L.; Mathew, S.; Ballon, G.; Chadburn, A.; Barouk, S.; Antonicelli, G.; Leoncini, L.; Liu, Y.F.; Gogineni, S.; Tam, W.; et al. A20 (TNFAIP3) genetic alterations in EBV-associated AIDS-related lymphoma. Blood 2011, 117, 4852–4854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, K.L.; Miller, W.E.; Raab-Traub, N. The A20 protein interacts with the Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) and alters the LMP1/TRAF1/TRADD complex. Virology 1999, 264, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamzad, A.; Khakpour, N.; Gholamzad, M.; Roudaki Sarvandani, M.R.; Khosroshahi, E.M.; Asadi, S.; Rashidi, M.; Hashemi, M. Stem cell therapy for HTLV-1 induced adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATLL): A comprehensive review. Pathol.—Res. Pract. 2024, 255, 155172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, R.; Kang, X.; Niu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Wang, H. PCBP1 interacts with the HTLV-1 Tax oncoprotein to potentiate NF-κB activation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1375168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, Y.; Hamano, A.; Mochida, K.; Kakeya, A.; Uno, M.; Tsuruyama, E.; Ichikawa, H.; Tokunaga, F.; Utsunomiya, A.; Watanabe, T.; et al. A20 targets caspase-8 and FADD to protect HTLV-I-infected cells. Leukemia 2016, 30, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laherty, C.D.; Perkins, N.D.; Dixit, V.M. Human T cell leukemia virus type I Tax and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate induce expression of the A20 zinc finger protein by distinct mechanisms involving nuclear factor kappa B. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 5032–5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujari, R.; Hunte, R.; Thomas, R.; van der Weyden, L.; Rauch, D.; Ratner, L.; Nyborg, J.K.; Ramos, J.C.; Takai, Y.; Shembade, N. Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) tax requires CADM1/TSLC1 for inactivation of the NF-κB inhibitor A20 and constitutive NF-κB signaling. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.C.; Fass, D.; Berger, J.M.; Kim, P.S. Core Structure of gp41 from the HIV Envelope Glycoprotein. Cell 1997, 89, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gorman, J.; Tsybovsky, Y.; Lu, M.; Liu, Q.; Gopan, V.; Singh, M.; Lin, Y.; Miao, H.; Seo, Y.; et al. Design of soluble HIV-1 envelope trimers free of covalent gp120-gp41 bonds with prevalent native-like conformation. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Sun, T.; Yao, P.; Chen, B.; Lu, X.; Han, D.; Wu, N. Differential expression of innate immunity regulation genes in chronic HIV-1 infected adults. Cytokine 2020, 126, 154871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitre, A.S.; Kattah, M.G.; Rosli, Y.Y.; Pao, M.; Deswal, M.; Deeks, S.G.; Hunt, P.W.; Abdel-Mohsen, M.; Montaner, L.J.; Kim, C.C.; et al. A20 upregulation during treated HIV disease is associated with intestinal epithelial cell recovery and function. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, B.; Song, X.T.; Rollins, L.; Berry, L.; Huang, X.F.; Chen, S.Y. Mucosal and systemic anti-HIV immunity controlled by A20 in mouse dendritic cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zammit, N.W.; Siggs, O.M.; Gray, P.E.; Horikawa, K.; Langley, D.B.; Walters, S.N.; Daley, S.R.; Loetsch, C.; Warren, J.; Yap, J.Y.; et al. Denisovan, modern human and mouse TNFAIP3 alleles tune A20 phosphorylation and immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1299–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagyinszky, E.; An, S.S.A. Genetic Mutations Associated with TNFAIP3 (A20) Haploinsufficiency and Their Impact on Inflammatory Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Effects | Virus | Mechanism of A20 Modulation | Clinical/Pathological Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proviral * | HCV | USF-1 degradation → A20 ↑ → enhances IRES-mediated translation; suppresses NF-κB and DC maturation | Promotes chronic infection, immune evasion |

| HRSV | A20+ABIN1/TAX1BP1 complex → suppresses IL-6, IFN- β | Maintains viral persistence in airway epithelium | |

| MeV | Monocytes: A20 ↑ → inhibits TRAF6 polyubiquitination → impairs formation/recruitment of the TAK1–TAB2–TRAF6 active complex → NF-κB suppressed | Cell-type–specific immune suppression | |

| VSV | A20 + ABIN1/TAX1BP1 complex antagonizes K63-linked polyubiquitination of TBK1/IKKε by disrupting the TRAF3–TBK1/IKKε module → IFN-I suppressed | Permissive environment for replication | |

| SeV | A20 binds TRIF and strongly blocks RIG-I/IRF3 activation | Suppression of the antiviral state → immune evasion | |

| HCoV-229E | Reduces IKKβ and NEMO; causes partial IκBα degradation; induces A20 | A20 knockdown lowers infection/replication proxy (~70% ↓ by N protein) | |

| HCMV | Early: IE1 activates NF-κB–responsive A20 promoter → A20 ↑; Late/high MOI: de novo viral gene products epigenetically limit A20 transcription | A20 is required for efficient HCMV growth; biphasic control is suggested to support productive infection | |

| BVDV-1 | A20 ↑ → NF-κB p65 phosphorylation ↓ → IL-8 ↓ | Establishes immunosuppressive state | |

| ALV-A | Virus–A20 feedback; A20 inhibits K63-polyubiquitination of TRAF6 (→ TRAF6 protein ↑), leads to STAT3 phosphorylation ↑ → c-Myc ↑ | In chickens, A20 up-regulation increases viremia and pathology; evidence supports contribution to oncogenesis | |

| Antiviral | Poliovirus | Despite host shutoff, A20 transcription preserved; knockdown ↑ viral RNA/yield | A20 acts as an antiviral restriction factor |

| CVB3 | Virus induces ADAR1 → promotes miR-1a-3p maturation → A20 ↓; A20 overexpression → cytokines and apoptosis ↓ | Protective against viral myocarditis | |

| Dual | ZIKV | Virus downregulates A20 protein post-transcriptionally (TNFAIP3 mRNA ↑ but A20 protein ↓; ZIKV C/NS5 implicated) → inhibits apoptosis/pyroptosis | Supports cell survival and potential persistence |

| IAV | Early: A20 ↑ → IRF3 inhibition, IFN-β suppressed (proviral); Late: NF-κB dampening reduces cytokine storm (host-protective) | Promotes replication in early phase; confers tissue-protective tolerance in later phase | |

| HBV | HBsAg → A20 ↑ (immune evasion); HBx/miR-125a post-transcriptional A20 ↓ → caspase-8 K63-Ub ↓, DISC ↑ → TRAIL-induced apoptosis ↑; TNFAIP3 TT>A variant increases susceptibility to chronic HBV | Linked to chronic infection and HCC progression | |

| EBV | LMP1 induces A20 via NF-κB; A20’s N-terminal DUB (OTU) domain binds IRF7 and reduces LMP1-driven K63-ubiquitination of IRF7 → IRF7 transactivation (IFN-I) suppressed; A20 also blocks p53-mediated apoptosis | Supports survival/persistence of infected cells (anti-apoptotic, IFN dampening); loss-of-function (deletions/mutations) of A20 in EBV-associated lymphomas sustains oncogenic NF-κB | |

| HTLV-1 | Tax → A20 ↑ via NF-κB; A20 (C-terminal ZF) binds caspase-8 and FADD → blocks caspase-8 recruitment/activation → apoptosis suppressed; Tax requires CADM1/TSLC1 to inhibit IKKα → TAX1BP1 phosphorylation, disabling the A20–TAX1BP1 negative-feedback and sustaining NF-κB | Promotes survival of infected T cells; maintains constitutive NF-κB; contributes to leukemogenesis (ATL) | |

| Context-dependent | HIV | Viremia: A20 ↓ (PBMCs/IECs) via IFN-I → epithelial barrier dysfunction (“leaky gut”); DCs: A20 restrains activation, blunting vaccine responses (mouse) | Drives mucosal immunopathology during viremia; DC A20 may limit vaccine efficacy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeon, H.; Lee, C. The Dual Role of A20 (TNFAIP3) in Viral Infection: A Context-Dependent Regulator of Immunity and Pathogenesis. Viruses 2025, 17, 1634. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121634

Jeon H, Lee C. The Dual Role of A20 (TNFAIP3) in Viral Infection: A Context-Dependent Regulator of Immunity and Pathogenesis. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1634. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121634

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeon, Haesung, and Choongho Lee. 2025. "The Dual Role of A20 (TNFAIP3) in Viral Infection: A Context-Dependent Regulator of Immunity and Pathogenesis" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1634. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121634

APA StyleJeon, H., & Lee, C. (2025). The Dual Role of A20 (TNFAIP3) in Viral Infection: A Context-Dependent Regulator of Immunity and Pathogenesis. Viruses, 17(12), 1634. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121634