Characterization of Novel Przondovirus Phage Adeo Infecting Klebsiella pneumoniae of the K39 Capsular Type

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phage Isolation, Propagation, and Purification

2.2. Determination of Phage and Depolymerase Specificity

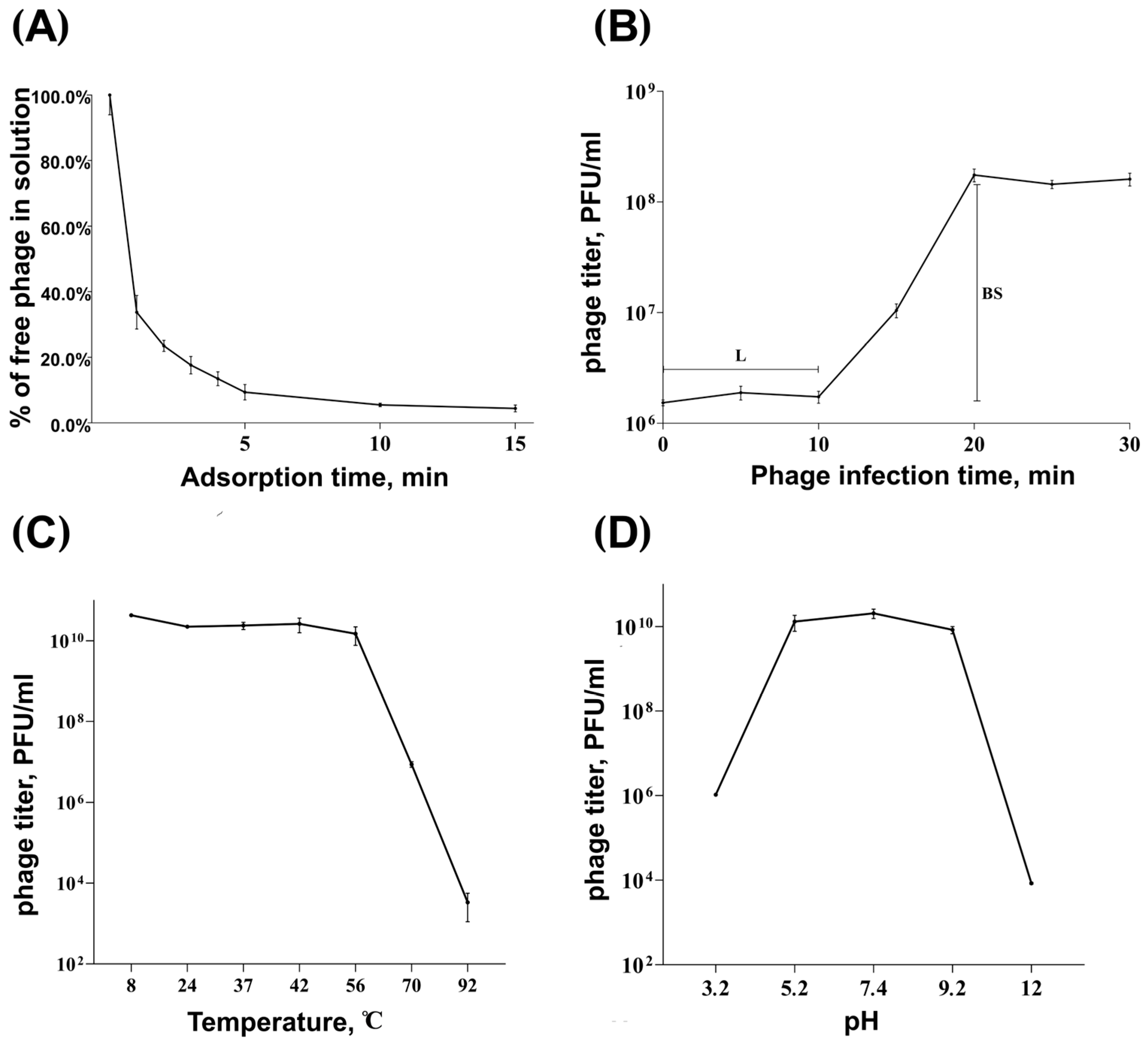

2.3. Phage Adsorption and One-Step Growth Experiments

2.4. Stability of Phage at Different Temperatures and pH Values

2.5. Electron Microscopy

2.6. DNA Isolation and Sequencing

2.7. Analysis of the Phage Genome and Proteins

2.8. Cloning, Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins

2.9. Phage Infection Inhibition Assay

3. Results

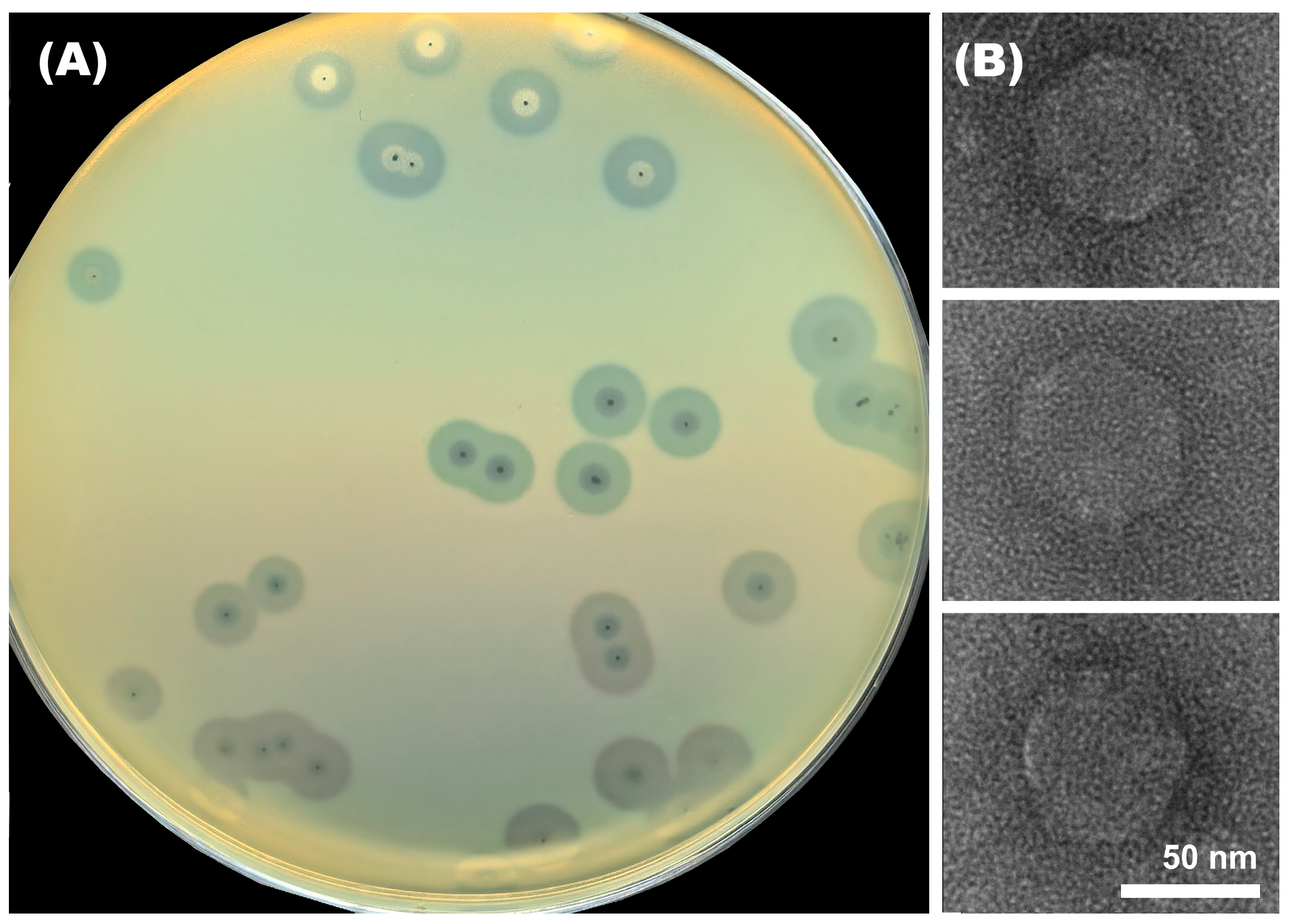

3.1. Morphological Characteristics and Infection Parameters of Phage Adeo

3.2. Analysis of Phage Genome and Phage-Derived Proteins

3.2.1. General Characterization of the Adeo Genome

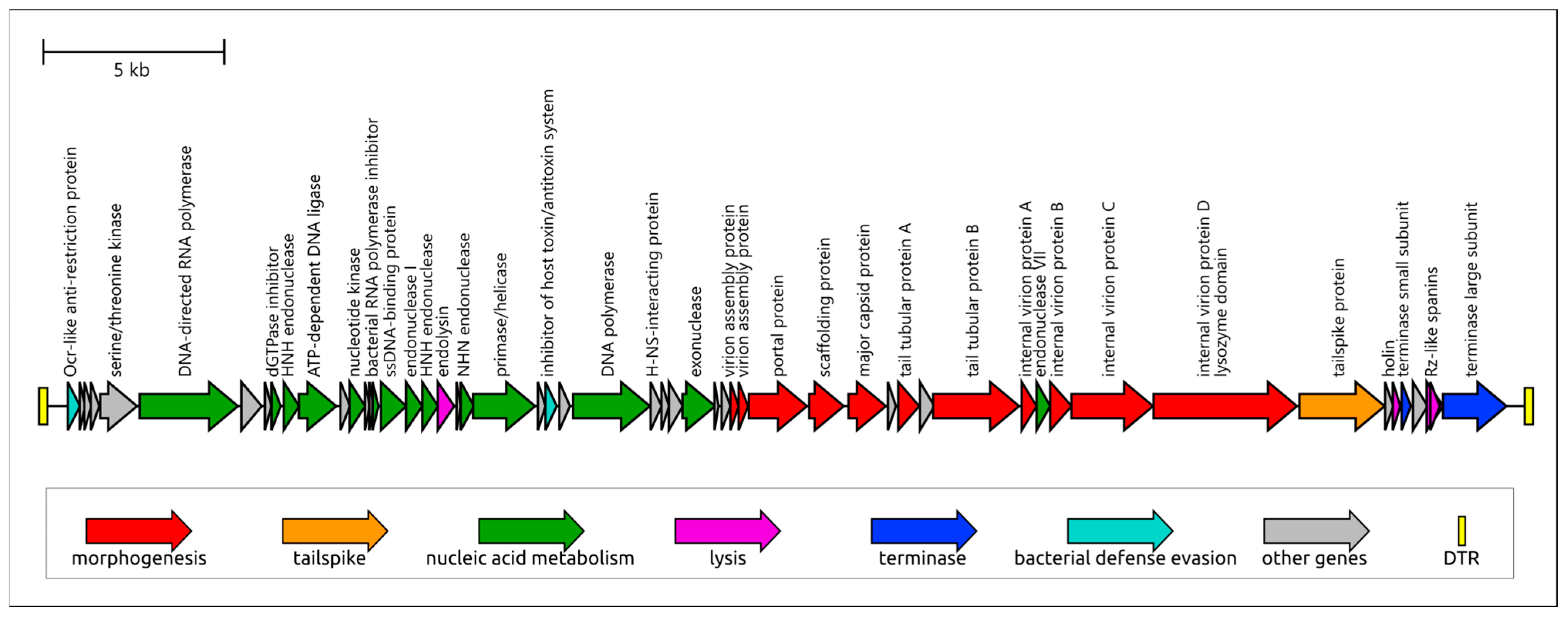

3.2.2. Genome Structure and Functional Modules

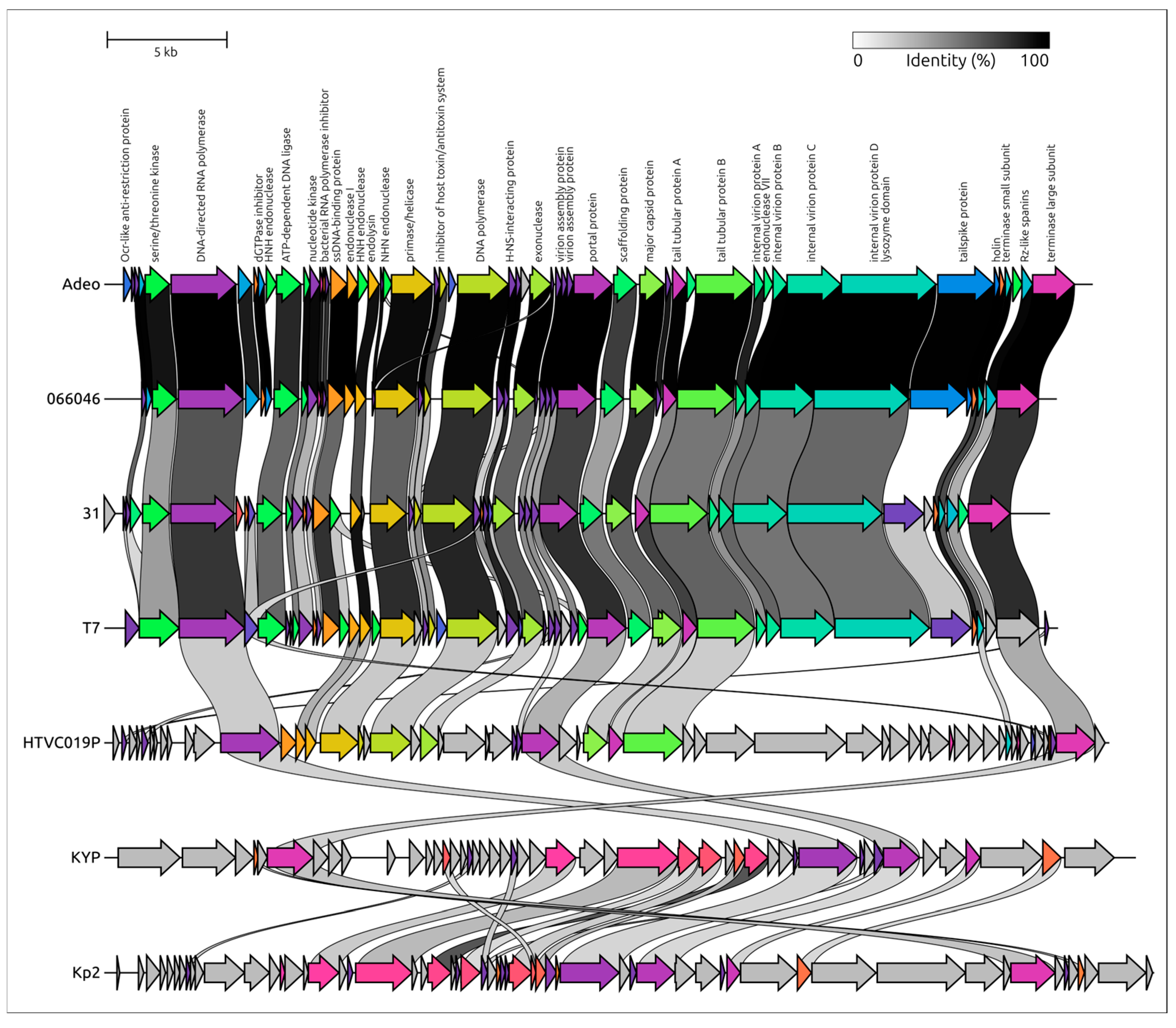

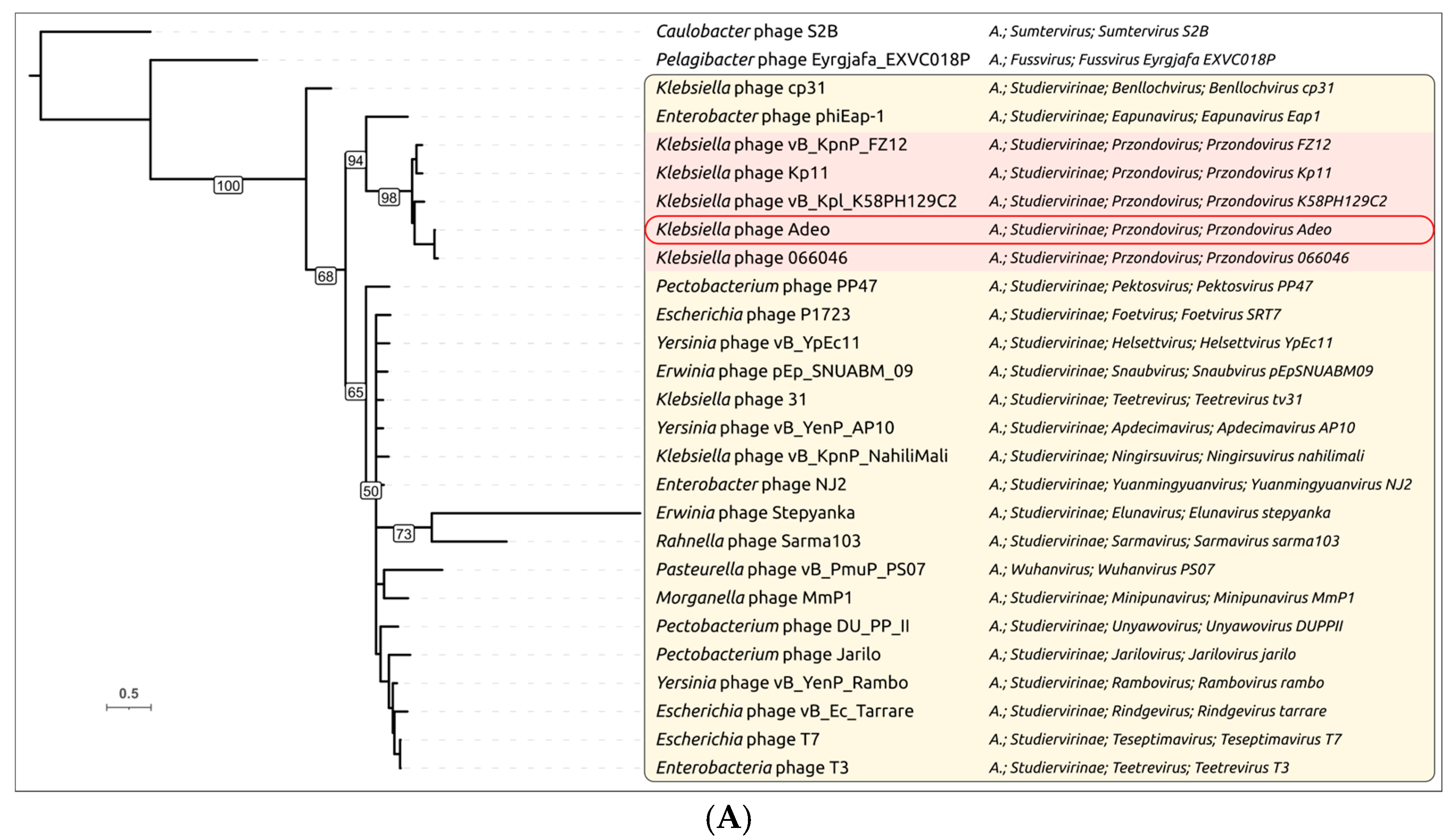

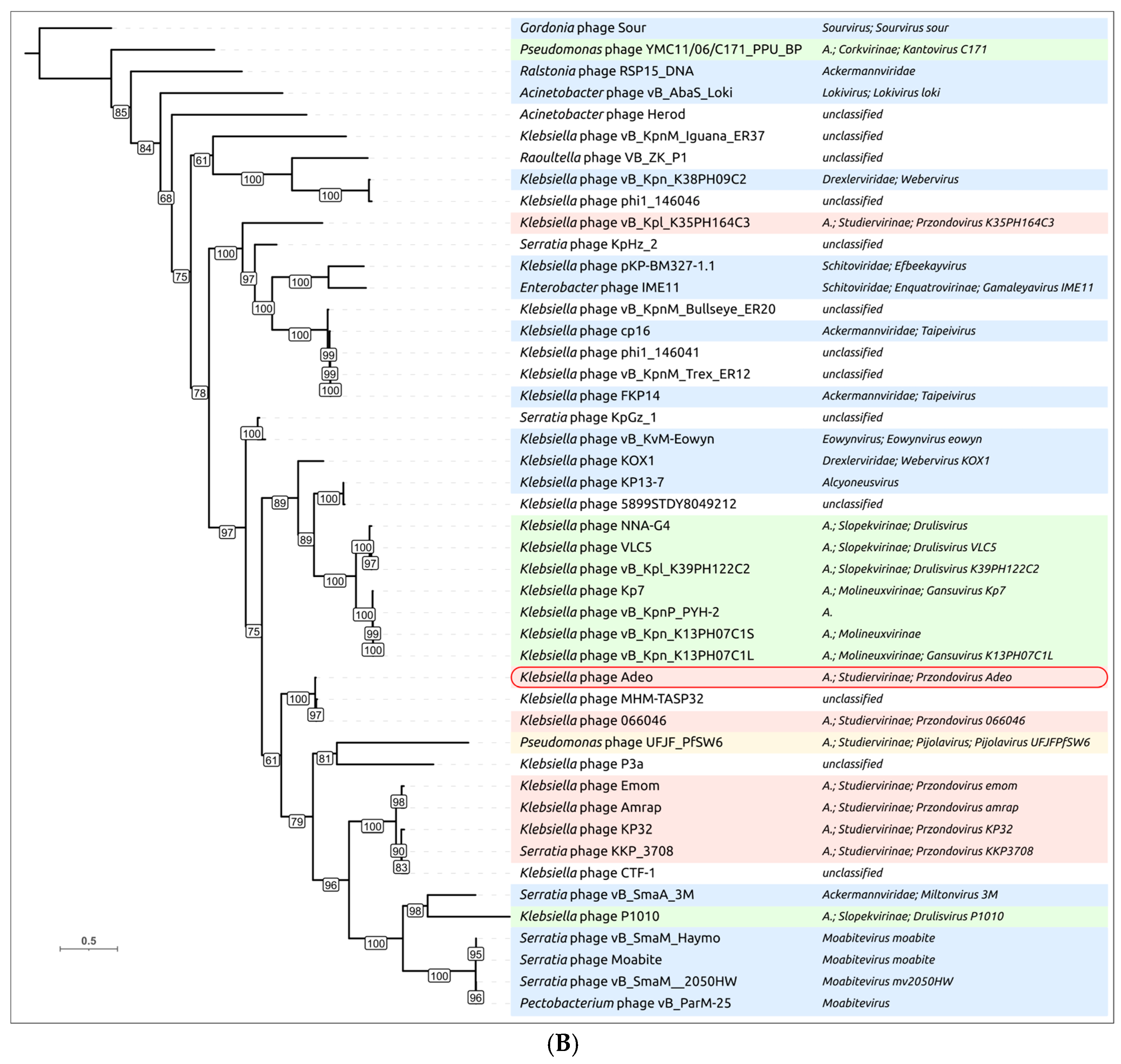

3.2.3. Taxonomy and Signature Genes Phylogeny

3.2.4. Tailspike Protein Analysis

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| bp | base pair |

| CFU | Colony forming Unit |

| PFU | Plaque Forming Unit |

| MOI | Multiplicity of Infection |

| EOP | Efficiency of Plating |

| ICTV | International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses |

References

- Chang, D.; Sharma, L.; Dela Cruz, C.S.; Zhang, D. Clinical epidemiology, risk factors, and control strategies of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 750662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, R.; Chakkour, M.; Zein El Dine, H.; Obaseki, E.F.; Obeid, S.T.; Jezzini, A.; Ghssein, G.; Ezzeddine, Z. General overview of Klebsiella pneumonia: Epidemiology and the role of siderophores in its pathogenicity. Biology 2024, 13, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Disease Outbreak News; Antimicrobial Resistance, Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae—Global Situation. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON527 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Ochońska, D.; Brzychczy-Włoch, M. Klebsiella pneumoniae—Taxonomy, occurrence, identification, virulence factors and pathogenicity. Adv. Microbiol. 2024, 63, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial antibiotic resistance: The most critical pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona, A.; De Santis, V.; Agarossi, A.; Prete, A.; Cattaneo, D.; Tomasini, G.; Bonetti, G.; Patroni, A.; Latronico, N. Antibiotic therapy strategies for treating gram-negative severe infections in the critically ill: A narrative review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance, to Guide Research, Development, and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-92-4-009346-1. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield, C.; Wear, S.S.; Sande, C. Assembly of bacterial capsular polysaccharides and exopolysaccharides. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 74, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comstock, L.E.; Kasper, D.L. Bacterial glycans: Key mediators of diverse host immune responses. Cell 2006, 126, 847–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendueles, O.; Garcia-Garcerà, M.; Néron, B.; Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P.C. Abundance and co-occurrence of extracellular capsules increase environmental breadth: Implications for the emergence of pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ophir, T.; Gutnick, D.L. A role for exopolysaccharides in the protection of microorganisms from desiccation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Haeze, W.; Holsters, M. Surface polysaccharides enable bacteria to evade plant immunity. Trends Microbiol. 2004, 12, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, M. Structural modifications of bacterial lipopolysaccharide that facilitate gram-negative bacteria evasion of host innate immunity. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.M.C.; Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Holt, K.E.; Wyres, K.L. Kaptive 2.0: Updated capsule and lipopolysaccharide locus typing for the Klebsiella pneumoniae species complex. Microb. Genom. 2022, 8, 000800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Fang, C.; Xiang, L.; Yin, M.; Qian, L.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y. Characterization and therapeutic potential of three depolymerases against K54 capsular-type Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blundell-Hunter, G.; Enright, M.C.; Negus, D.; Dorman, M.J.; Beecham, G.E.; Pickard, D.J.; Wintachai, P.; Voravuthikunchai, S.P.; Thomson, N.R.; Taylor, P.W. Characterisation of bacteriophage-encoded depolymerases selective for key Klebsiella pneumoniae capsular exopolysaccharides. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 686090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, B.; Squeglia, F.; Latka, A.; Privitera, M.; Olejniczak, S.; Switala, P.; Ruggiero, A.; Marasco, D.; Kramarska, E.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; et al. Klebsiella phage KP34gp57 capsular depolymerase structure and function: From a serendipitous finding to the design of active mini-enzymes against K. pneumoniae. mBio 2023, 14, e0132923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.N.; Parolis, H.; Dutton, G.G.; Leek, D.M. Klebsiella serotype K39: Structure of an unusual capsular antigen deduced by use of a viral endoglucosidase. Carbohydr. Res. 1987, 167, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fursova, N.K.; Astashkin, E.I.; Ershova, O.N.; Aleksandrova, I.A.; Savin, I.A.; Novikova, T.S.; Fedyukina, G.N.; Kislichkina, A.A.; Fursov, M.V.; Kuzina, E.S.; et al. Multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae causing severe infections in the Neuro-ICU. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoilova, A.A.; Kraeva, L.A.; Mikhailov, N.V.; Saitova, A.T.; Polev, D.E.; Vashukova, M.A.; Gordeeva, S.A.; Smirnova, E.V.; Beljatich, L.I.; Dolgova, A.S.; et al. Genomic analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains virulence and antibiotic resistance. Russ. J. Infect. Immun. 2024, 14, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolupaeva, N.V.; Kolupaeva, L.V.; Evseev, P.V.; Skryabin, Y.P.; Lazareva, E.B.; Chernenkaya, T.V.; Volozhantsev, N.V.; Popova, A.V. Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates obtained from intensive care unit patients in 2024: General characterization, prophages, depolymerases and esterases of phage origin. Viruses 2025, 17, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solovieva, E.V.; Myakinina, V.P.; Kislichkina, A.A.; Krasilnikova, V.M.; Verevkin, V.V.; Mochalov, V.V.; Lev, A.I.; Fursova, N.K.; Volozhantsev, N.V. Comparative genome analysis of novel Podoviruses lytic for hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae of K1, K2, and K57 capsular types. Virus Res. 2018, 243, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, T.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, F.; Xie, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; et al. Characterization and genome analysis of novel Klebsiella phage Henu1 with lytic activity against clinical strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 2389–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, K.; Shi, X.; Yang, K.; Xu, Q.; Wang, F.; Chen, S.; Xu, T.; Liu, J.; Wen, W.; Chen, R.; et al. Phage-antibiotic synergy suppresses resistance emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae by altering the evolutionary fitness. mBio 2024, 15, e0139324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Huang, X.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, J.; Xiang, Y. Isolation and characterization of three lytic podo-bacteriophages with two receptor recognition modules against multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volozhantsev, N.V.; Borzilov, A.I.; Shpirt, A.M.; Krasilnikova, V.M.; Verevkin, V.V.; Denisenko, E.A.; Kombarova, T.I.; Shashkov, A.S.; Knirel, Y.A.; Dyatlov, I.A. Comparison of the therapeutic potential of bacteriophage KpV74 and phage-derived depolymerase (β-glucosidase) against Klebsiella pneumoniae capsular type K2. Virus Res. 2022, 322, 198951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, M.; Osbelt, L.; Passet, V.; Gravey, F.; Megrian, D.; Strowig, T.; Rodrigues, C.; Brisse, S. Phages against noncapsulated Klebsiella pneumoniae: Broader host range, slower resistance. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0481222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Tian, F.; Feng, Q.; Li, F.; Tong, Y. Genomic characterization of the novel bacteriophage IME183, infecting Klebsiella pneumoniae of capsular type K2. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majkowska-Skrobek, G.; Latka, A.; Berisio, R.; Squeglia, F.; Maciejewska, B.; Briers, Y.; Drulis-Kawa, Z. Phage-borne depolymerases decrease Klebsiella pneumoniae resistance to innate defense mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, P.F.; Lin, H.H.; Lin, T.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wang, J.T. Two T7-like bacteriophages, K5-2 and K5-4, each encodes two capsule depolymerases: Isolation and functional characterization. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, H.; Lemire, S.; Pires, D.P.; Lu, T.K. Engineering modular viral scaffolds for targeted bacterial population editing. Cell Syst. 2015, 1, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukianova, A.A.; Shneider, M.M.; Evseev, P.V.; Egorov, M.V.; Kasimova, A.A.; Shpirt, A.M.; Shashkov, A.S.; Knirel, Y.A.; Kostryukova, E.S.; Miroshnikov, K.A. Depolymerisation of the Klebsiella pneumoniae capsular polysaccharide K21 by Klebsiella phage K5. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, R.; Xu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, X.; Qiu, J.; Liu, Q.; He, P.; Li, Q. A novel polysaccharide depolymerase encoded by the phage SH-KP152226 confers specific activity against multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae via biofilm degradation. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Zong, Z. Lytic phages against ST11 K47 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and the corresponding phage resistance mechanisms. mSphere 2022, 7, e0008022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.J.; Lin, T.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lai, P.H.; Tsai, Y.T.; Hsu, C.R.; Hsieh, P.F.; Lin, Y.T.; Wang, J.T. Identification of three podoviruses infecting Klebsiella encoding capsule depolymerases that digest specific capsular types. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodnichev, R.B.; Kornienko, M.A.; Bespiatykh, D.A.; Malakhova, M.V.; Krivulia, A.O.; Veselovsky, V.A.; Bespyatykh, Y.A.; Goloshchapov, O.V.; Chernenkaya, T.V.; Shitikov, E.A. Isolation and characterization of virulent bacteriophages against Klebsiella pneumoniae of significant capsular types. Extrem. Med. 2023, 25, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xiao, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Qi, W.; Qi, Z.; Chen, L.; Du, H.; Zhang, W. Characterization and genome analysis of Klebsiella phage P509, with lytic activity against clinical carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae of the KL64 capsular type. Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 2799–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Li, P.; Chen, L.; Guo, G.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, L.; Du, H.; Zhang, W. Identification of a phage-derived depolymerase specific for KL64 capsule of Klebsiella pneumoniae and its anti-biofilm effect. Virus Genes 2021, 57, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Sheng, Y.; Ma, R.; Xu, M.; Liu, F.; Qin, R.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, X.; He, P. Identification of a depolymerase specific for K64-serotype Klebsiella pneumoniae: Potential applications in capsular typing and treatment. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckstein, S.; Stender, J.; Mzoughi, S.; Vogele, K.; Kühn, J.; Friese, D.; Bugert, C.; Handrick, S.; Ferjani, M.; Wölfel, R.; et al. Isolation and characterization of lytic phage TUN1 specific for Klebsiella pneumoniae K64 clinical isolates from Tunisia. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Feng, Y.; McNally, A.; Zong, Z. Characterization of phage resistance and phages capable of intestinal decolonization of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in mice. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Fang, Q.; Zong, Z. Interruption of capsular polysaccharide biosynthesis gene wbaZ by insertion sequence IS903B mediates resistance to a lytic phage against ST11 K64 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. mSphere 2022, 7, e0051822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, R.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Bai, Y.; Song, Z.; Lu, X.; et al. Isolation and characterization of lytic bacteriophage vB_KpnP_23: A promising antimicrobial candidate against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Virus Res. 2024, 350, 199473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Shan, B.; Hu, X.; Xue, L.; Song, G.; He, P.; Yang, X. Identification of a novel phage depolymerase against ST11 K64 carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and its therapeutic potential. J. Bacteriol. 2025, 207, e0038724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiry, D.; Passet, V.; Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.; Lood, C.; Wagemans, J.; De Sordi, L.; van Noort, V.; Dufour, N.; Debarbieux, L.; Mainil, J.G.; et al. New bacteriophages against emerging lineages ST23 and ST258 of Klebsiella pneumoniae and efficacy assessment in Galleria mellonella larvae. Viruses 2019, 11, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.H. Bacteriophages; Interscience Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Kutter, E. Phage host range and efficiency of plating. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Fritsch, E.F.; Maniatis, T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 1989; ISBN 0-87969-309-6. [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: A new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraru, C.; Varsani, A.; Kropinski, A.M. VIRIDIC—A novel tool to calculate the intergenomic similarities of prokaryote-infecting viruses. Viruses 2020, 12, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L. Dali server: Structural unification of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, L. Using Dali for protein structure comparison. In Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2112, pp. 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Huynh, W.; Chalil, R.; Smith, K.W.; Raphenya, A.R.; Wlodarski, M.A.; Edalatmand, A.; Petkau, A.; Syed, S.A.; Tsang, K.K.; et al. CARD 2023: Expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, B.; Zheng, D.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. VFDB 2025: An integrated resource for exploring anti-virulence compounds. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, 871–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, L.; Stephens, A.; Nam, S.-Z.; Rau, D.; Kübler, J.; Lozajic, M.; Gabler, F.; Söding, J.; Lupas, A.N.; Alva, V. A completely reimplemented MPI bioinformatics toolkit with a new HHpred server at its core. J. Mol. Biol. 2018, 430, 2237–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchurova, A.S.; Shneider, M.M.; Arbatsky, N.P.; Shashkov, A.S.; Chizhov, A.O.; Skryabin, Y.P.; Mikhaylova, Y.V.; Sokolova, O.S.; Shelenkov, A.A.; Miroshnikov, K.A.; et al. Novel Acinetobacter baumannii myovirus TaPaz encoding two tailspike depolymerases: Characterization and host-recognition strategy. Viruses 2021, 13, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evseev, P.V.; Lukianova, A.A.; Shneider, M.M.; Korzhenkov, A.A.; Bugaeva, E.N.; Kabanova, A.P.; Miroshnikov, K.K.; Kulikov, E.E.; Toshchakov, S.V.; Ignatov, A.N.; et al. Origin and evolution of Studiervirinae bacteriophages infecting Pectobacterium: Horizontal transfer assists adaptation to new niches. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeckman, J.; Korn, A.; Yao, G.; Ravindran, A.; Gonzalez, C.; Gill, J. Sheep in Wolves’ Clothing: Temperate T7-like bacteriophages and the origins of the Autographiviridae. Virology 2022, 568, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujak, K.; Decewicz, P.; Rosinska, J.M.; Radlinska, M. Genome study of a novel virulent phage vB_SspS_KASIA and Mu-like prophages of Shewanella sp. M16 provides insights into the genetic diversity of the Shewanella virome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Qin, F.; Zhang, R.; Giovannoni, S.J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, J.; Du, S.; Rensing, C. Pelagiphages in the Podoviridae family integrate into host genomes. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.M.; Kang, C. Lysis delay and burst shrinkage of coliphage T7 by deletion of terminator Tφ reversed by deletion of early genes. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 2107–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkinshaw, M.D.; Taylor, P.; Sturrock, S.S.; Atanasiu, C.; Berge, T.; Henderson, R.M.; Edwardson, J.M.; Dryden, D.T.F. Structure of Ocr from bacteriophage T7, a protein that mimics B-form DNA. Mol. Cell 2002, 9, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaev, A.; Drobiazko, A.; Sierro, N.; Gordeeva, J.; Yosef, I.; Qimron, U.; Ivanov, N.V.; Severinov, K. Phage T7 DNA mimic protein Ocr is a potent inhibitor of BREX defence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 5397–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summer, E.J.; Berry, J.; Tran, T.A.T.; Niu, L.; Struck, D.K.; Young, R. Rz/Rz1 Lysis gene equivalents in phages of gram-negative hosts. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 373, 1098–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Kropinski, A.M.; Adriaenssens, E.M. A Roadmap for genome-based phage taxonomy. Viruses 2021, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavrich, T.N.; Hatfull, G.F. Bacteriophage evolution differs by host, lifestyle and genome. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura de Sousa, J.A.; Pfeifer, E.; Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P.C. Causes and consequences of bacteriophage diversification via genetic exchanges across lifestyles and bacterial taxa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 2497–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Xiao, H.; Pang, H.; Wang, L.; Song, J.; Chen, W.; Cheng, L.; Liu, H. Conformational changes in and translocation of small proteins: Insights into the ejection mechanism of podophages. J. Virol. 2025, 99, e01249-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheetham, M.J.; Huo, Y.; Stroyakovski, M.; Cheng, L.; Wan, D.; Dell, A.; Santini, J.M. Specificity and diversity of Klebsiella pneumoniae phage-encoded capsule depolymerases. Essays Biochem. 2024, 68, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, A.; Pulido-Cid, M.; Chagoyen, M.; Arranz, R.; González-García, V.A.; Garcia-Doval, C.; Castón, J.R.; Valpuesta, J.M.; van Raaij, M.J.; Martín-Benito, J.; et al. Structural characterization of the bacteriophage T7 tail machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 26290–26299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Marion, W.R.; Cingolani, G.; Prevelige, P.E.; Johnson, J.E. Three-dimensional structure of the bacteriophage P22 tail machine. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latka, A.; Leiman, P.G.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Briers, Y. Modeling the architecture of depolymerase-containing receptor binding proteins in Klebsiella phages. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latka, A.; Lemire, S.; Grimon, D.; Dams, D.; Maciejewska, B.; Lu, T.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Briers, Y. Engineering the modular receptor-binding proteins of Klebsiella phages switches their capsule serotype specificity. mBio 2021, 12, e00455-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pas, C.; Latka, A.; Fieseler, L.; Briers, Y. Phage tailspike modularity and horizontal gene transfer reveals specificity towards E. coli O-antigen serogroups. Virol. J. 2023, 20, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kolupaeva, N.V.; Evseev, P.V.; Avdeeva, V.A.; Sizova, A.A.; Suzina, N.E.; Volozhantsev, N.V.; Popova, A.V. Characterization of Novel Przondovirus Phage Adeo Infecting Klebsiella pneumoniae of the K39 Capsular Type. Viruses 2025, 17, 1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121600

Kolupaeva NV, Evseev PV, Avdeeva VA, Sizova AA, Suzina NE, Volozhantsev NV, Popova AV. Characterization of Novel Przondovirus Phage Adeo Infecting Klebsiella pneumoniae of the K39 Capsular Type. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121600

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolupaeva, Nadezhda V., Peter V. Evseev, Victoria A. Avdeeva, Angelika A. Sizova, Natalia E. Suzina, Nikolay V. Volozhantsev, and Anastasia V. Popova. 2025. "Characterization of Novel Przondovirus Phage Adeo Infecting Klebsiella pneumoniae of the K39 Capsular Type" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121600

APA StyleKolupaeva, N. V., Evseev, P. V., Avdeeva, V. A., Sizova, A. A., Suzina, N. E., Volozhantsev, N. V., & Popova, A. V. (2025). Characterization of Novel Przondovirus Phage Adeo Infecting Klebsiella pneumoniae of the K39 Capsular Type. Viruses, 17(12), 1600. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121600