Nowcast-It: A Practical Toolbox for Real-Time Adjustment of Reporting Delays in Epidemic Surveillance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Conceptual Positioning of Nowcast-It

2.2. Implementation

- Installing the toolbox

- Download the R code located in the ‘Reporting delay adjustment code’ folder from the online GitHub repository: https://github.com/atariq2891 (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Create an ‘input’ folder in your working directory where your input data will be stored.

- Create an ‘output’ folder in your working directory where the output files will be stored.

- Create a ‘Functions’ folder in your working directory where the function files will be stored.

- Download and install R-Studio Version 2023.06.1+524.

- Open an R session so a window called R console appears.

- Install and run xQuartz (XQuartz-2.8.5.pkg) version 8.2.5 from https://www.xquartz.org/ to visualize the figures produced by the reporting delay adjustment algorithm.

2.3. Overview of the Toolbox Functions

2.4. Data Resolution

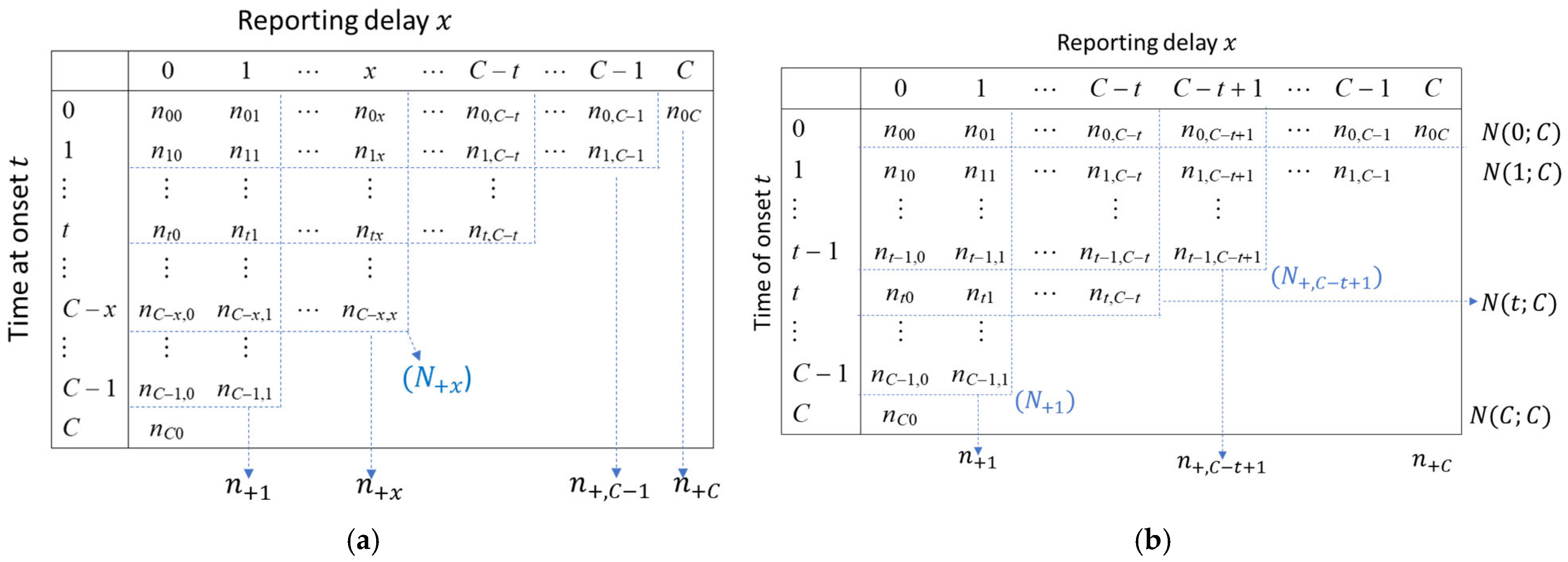

2.5. Reporting Delay Adjustment Methodology

- Nowcasting approach

2.6. Assuming Non-Stationarity in the Reporting Delays

2.7. Evaluating the Performance of Nowcasts, Performance Metrics

3. Results and Discussion

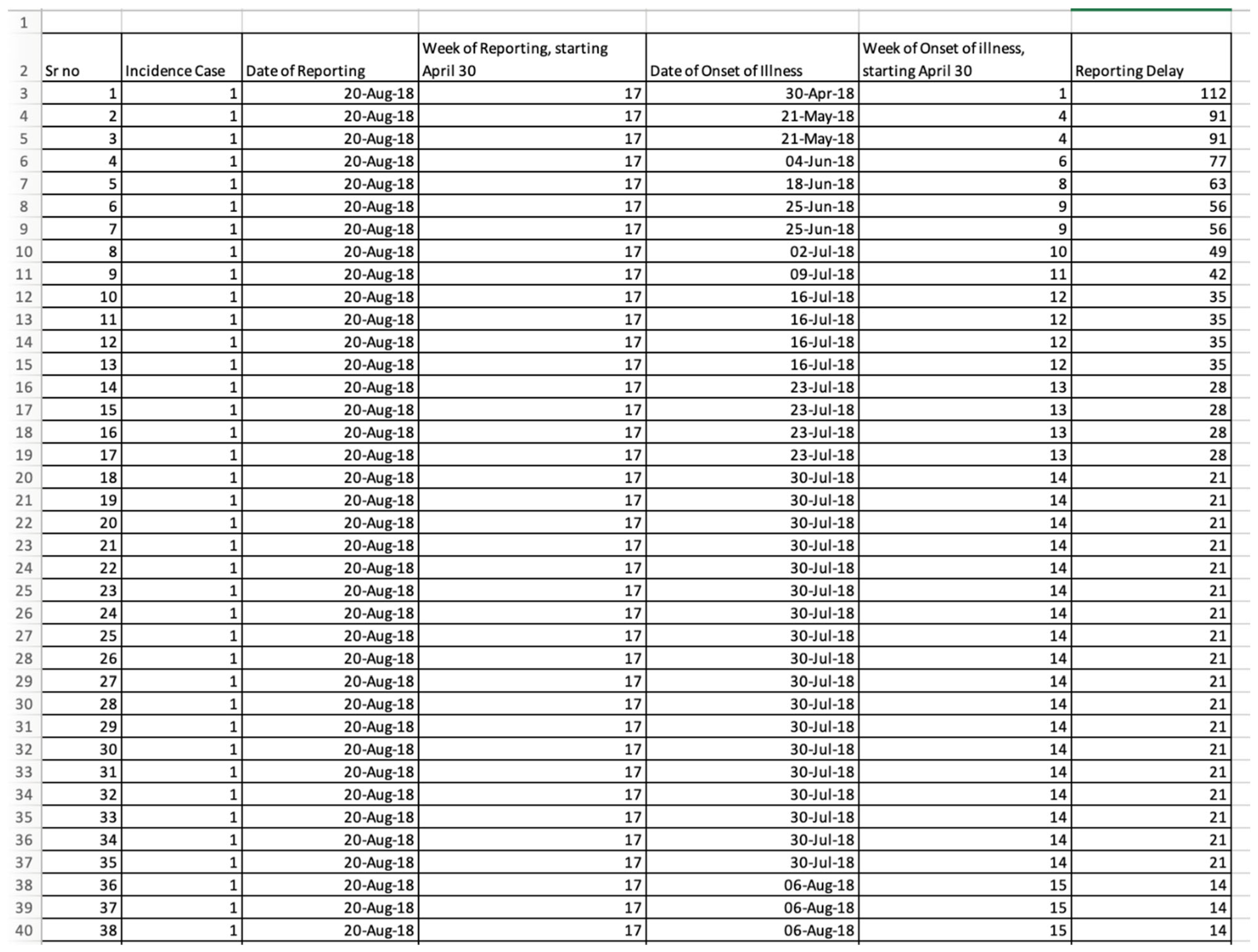

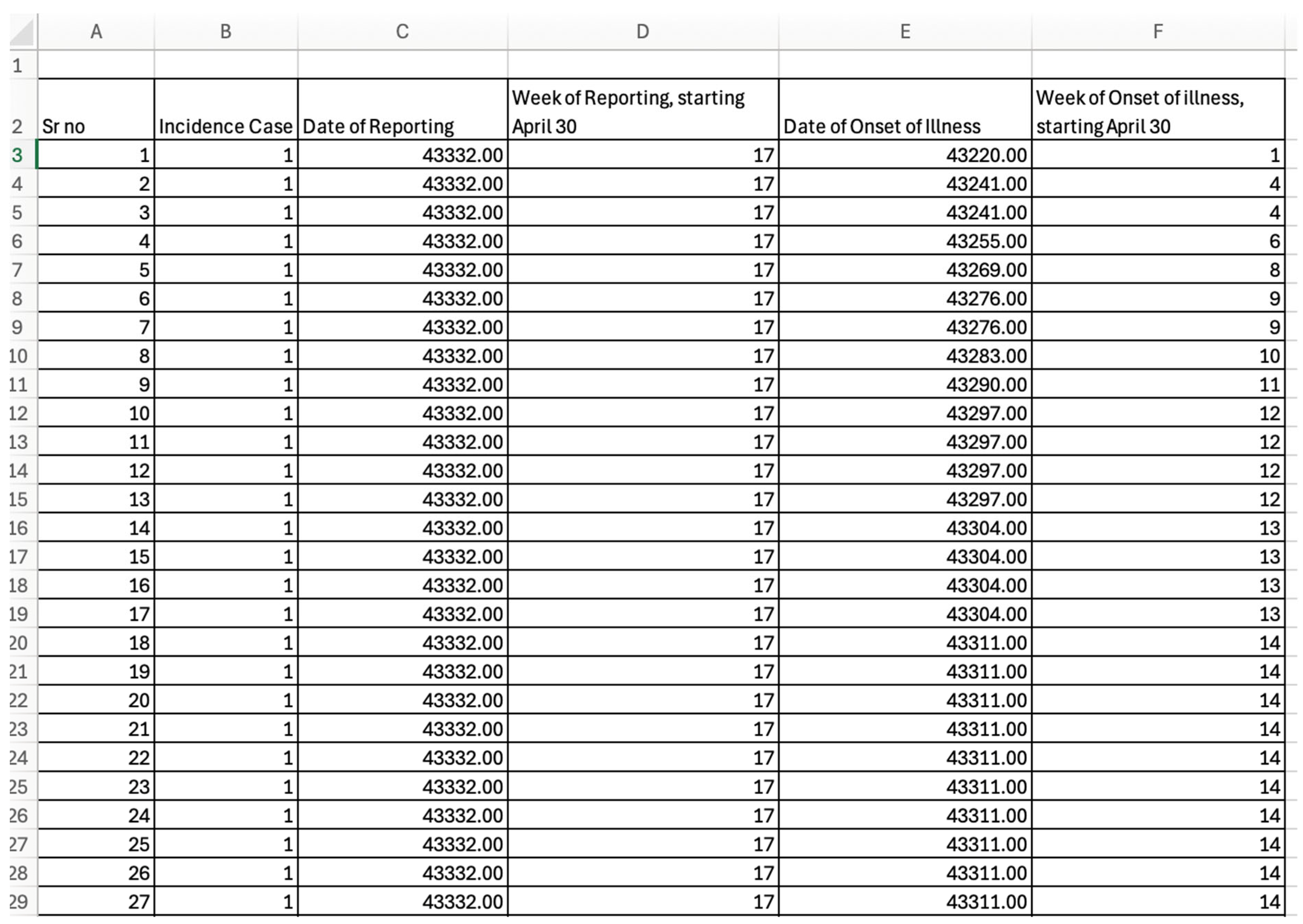

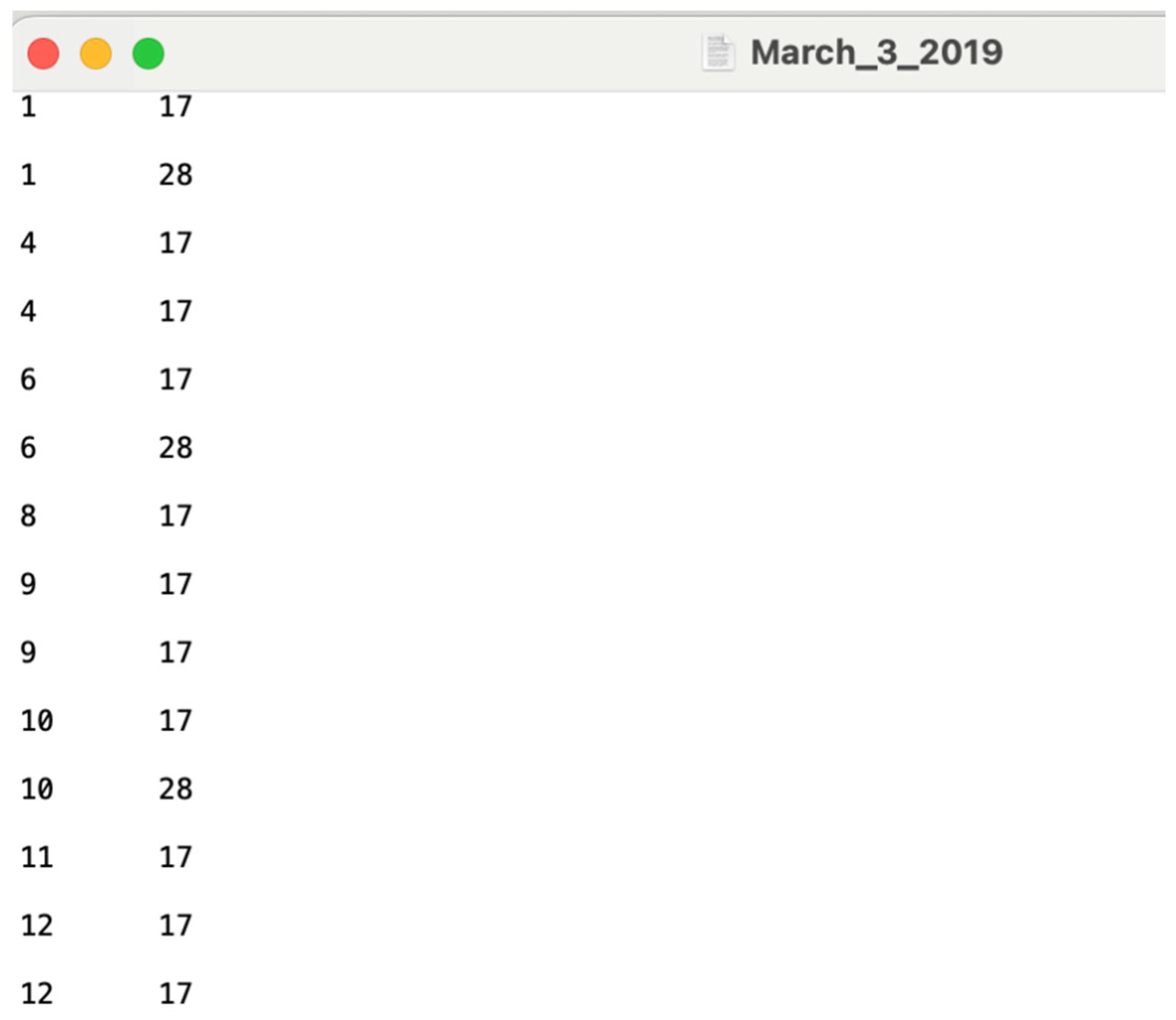

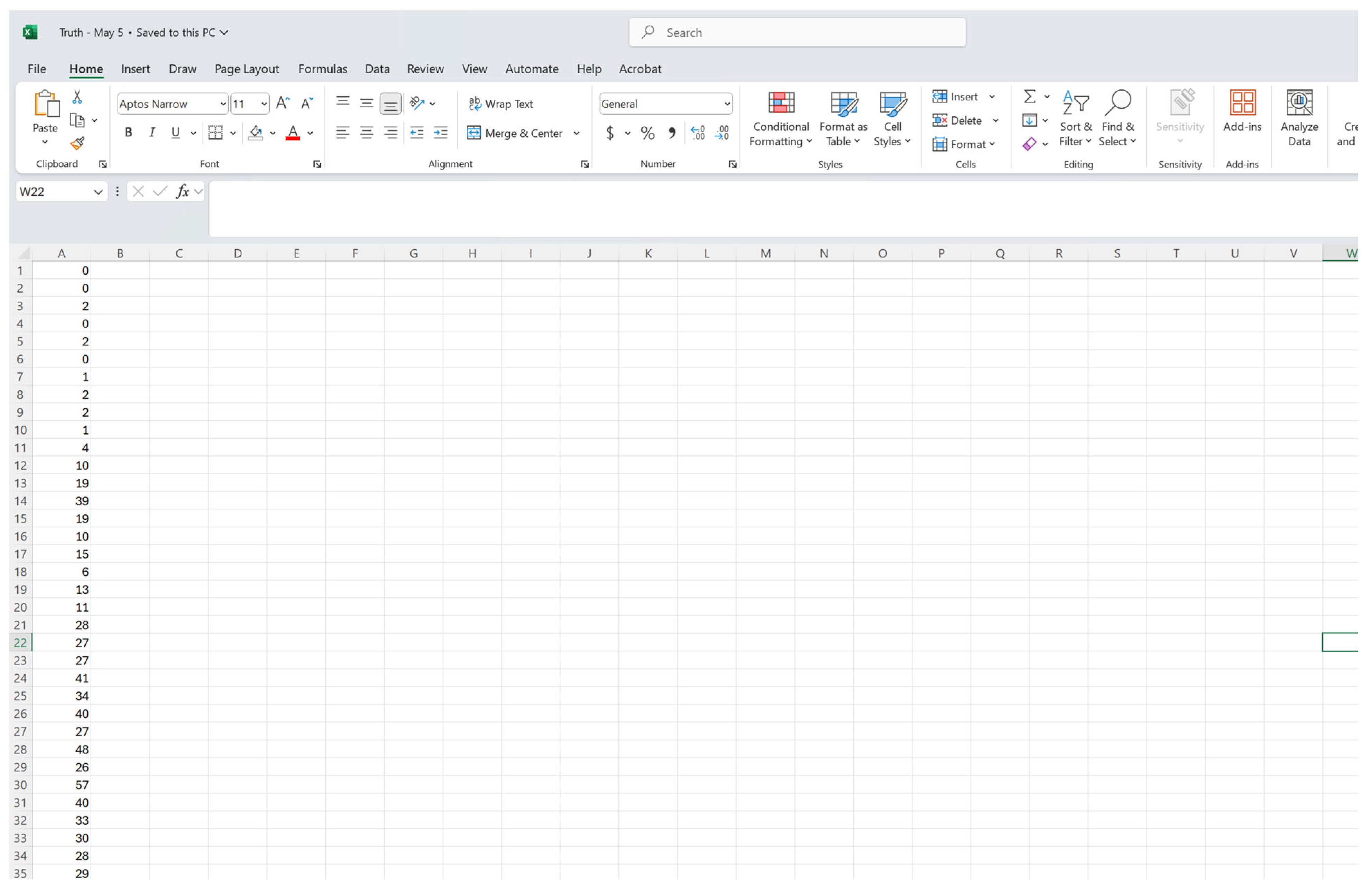

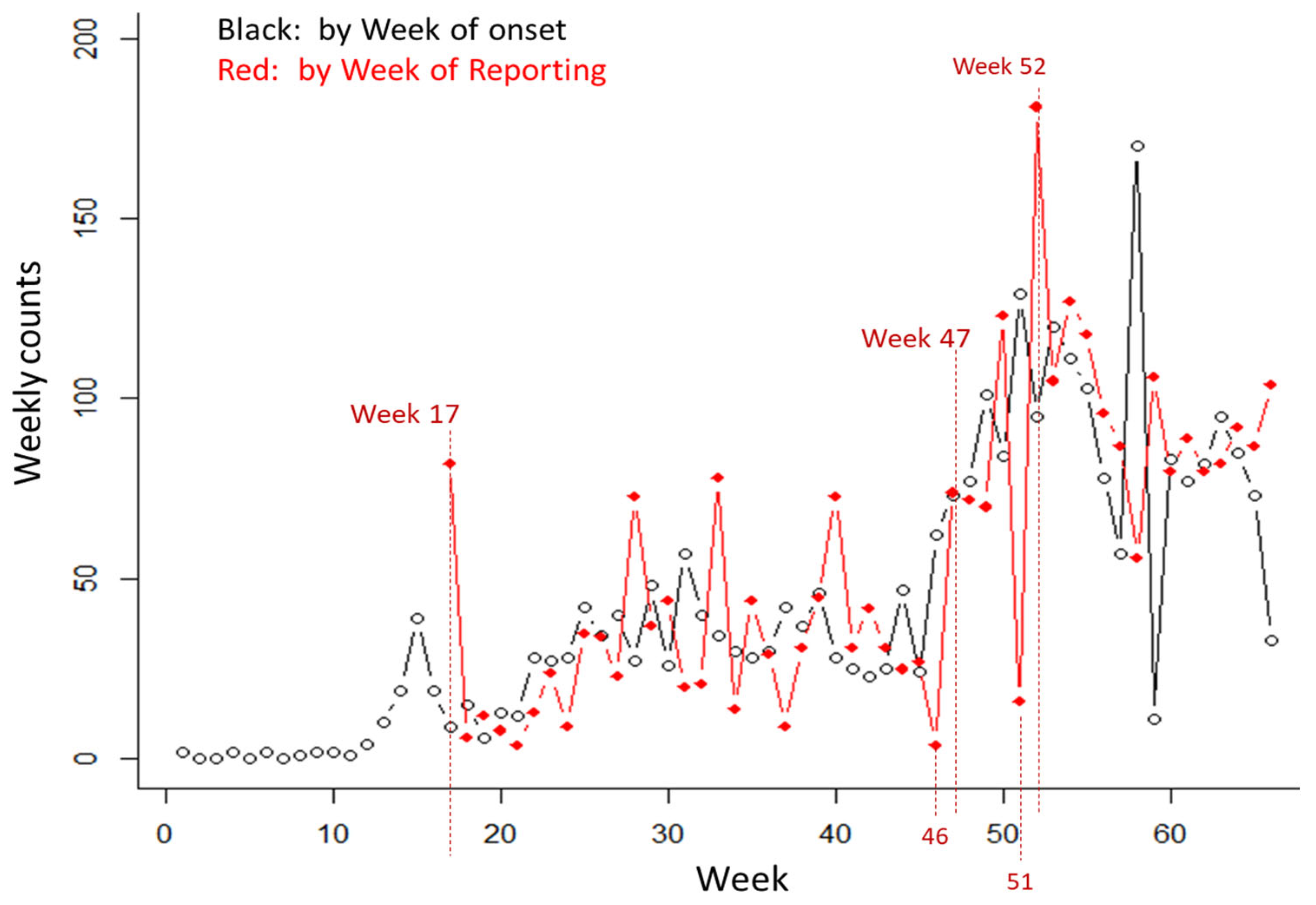

3.1. The Input Data Set

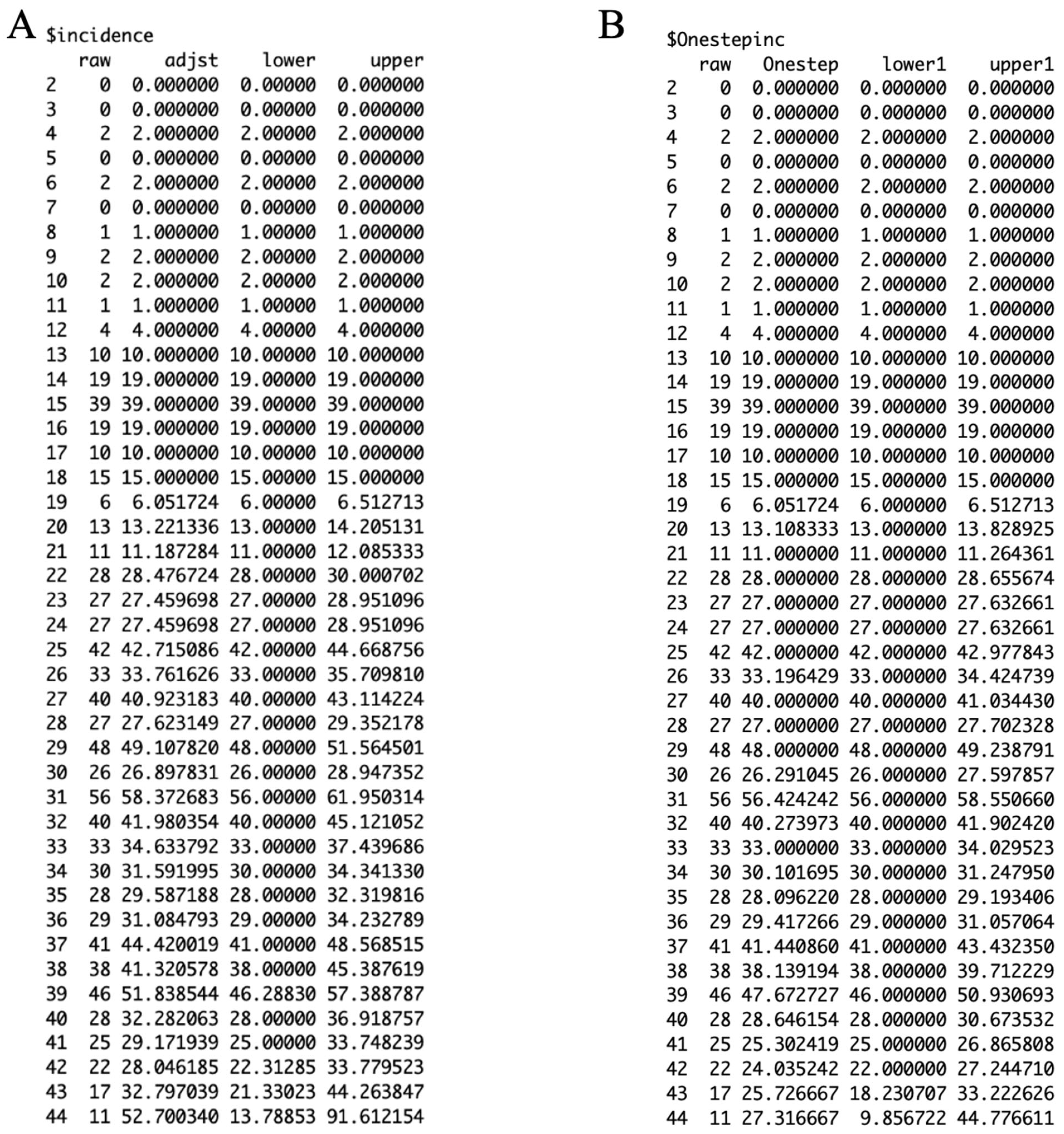

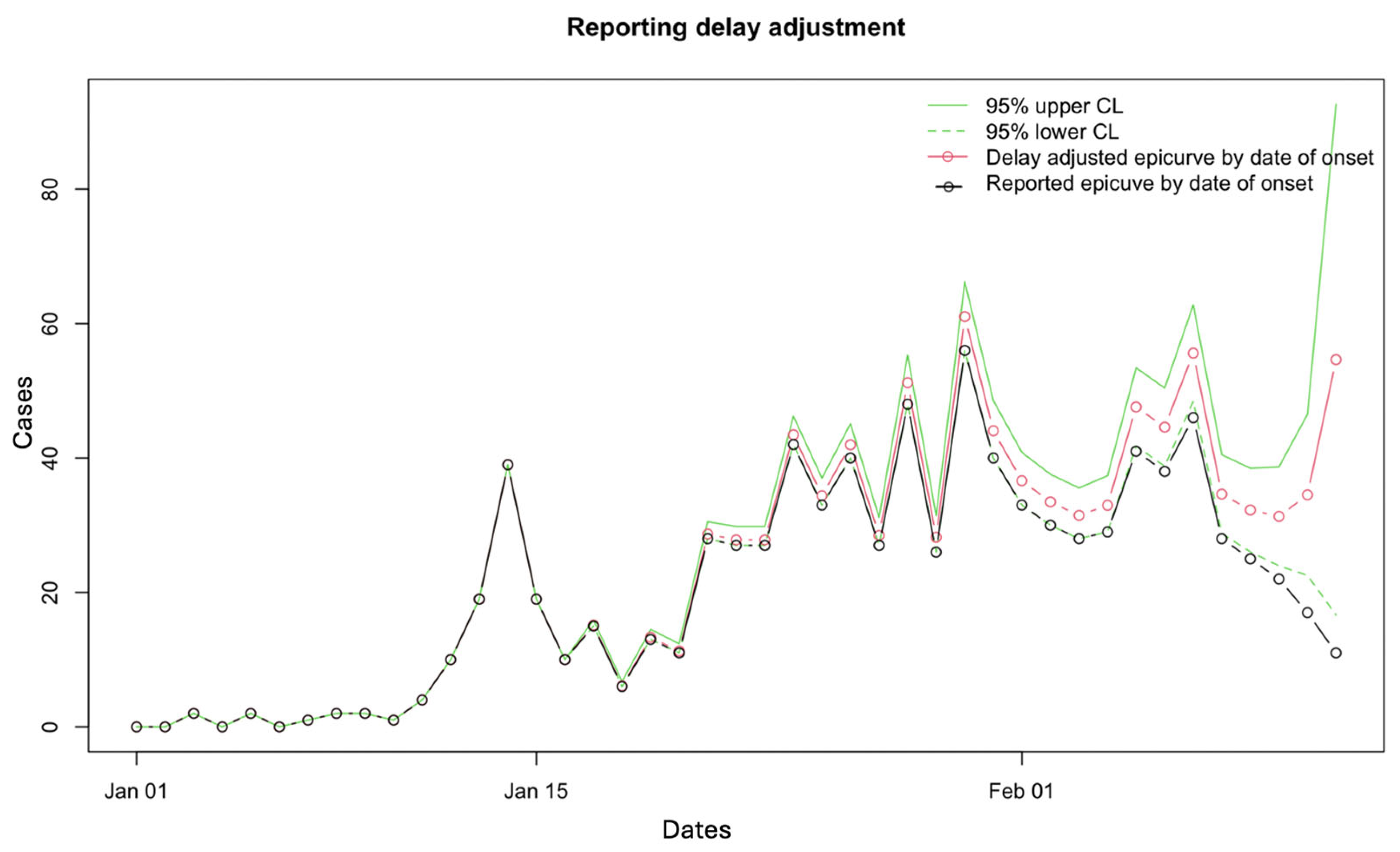

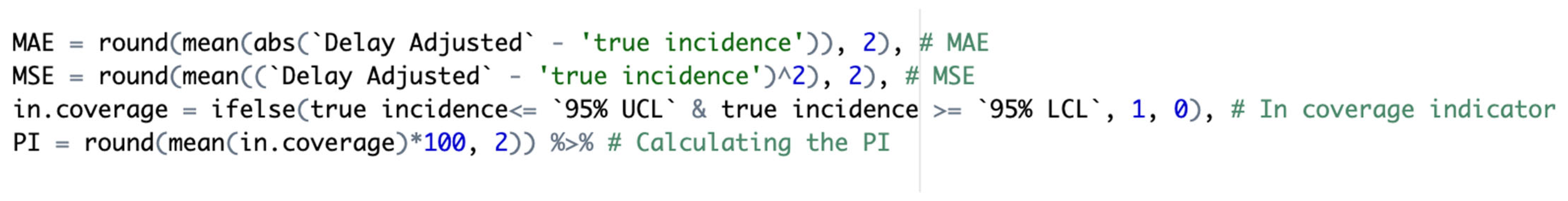

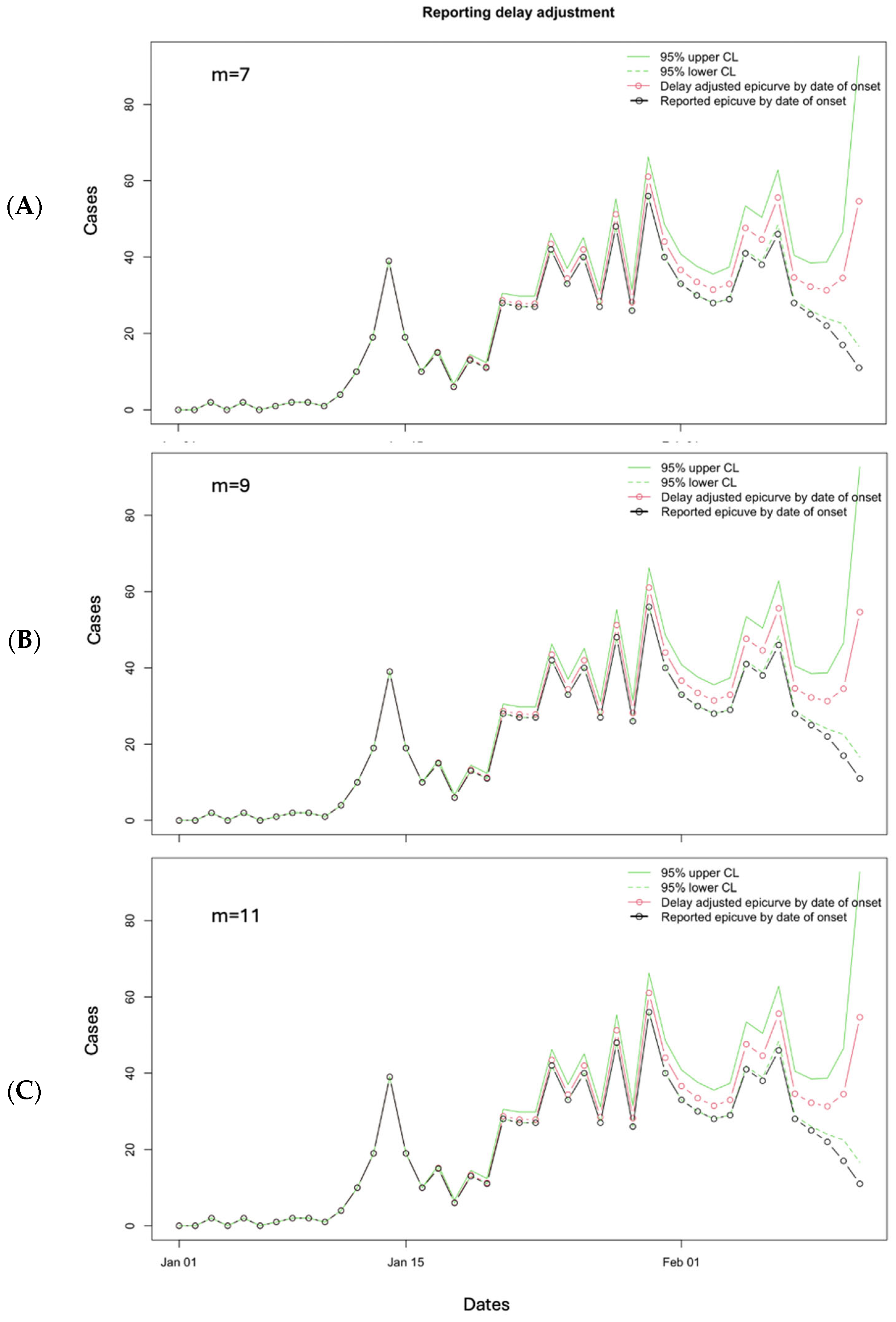

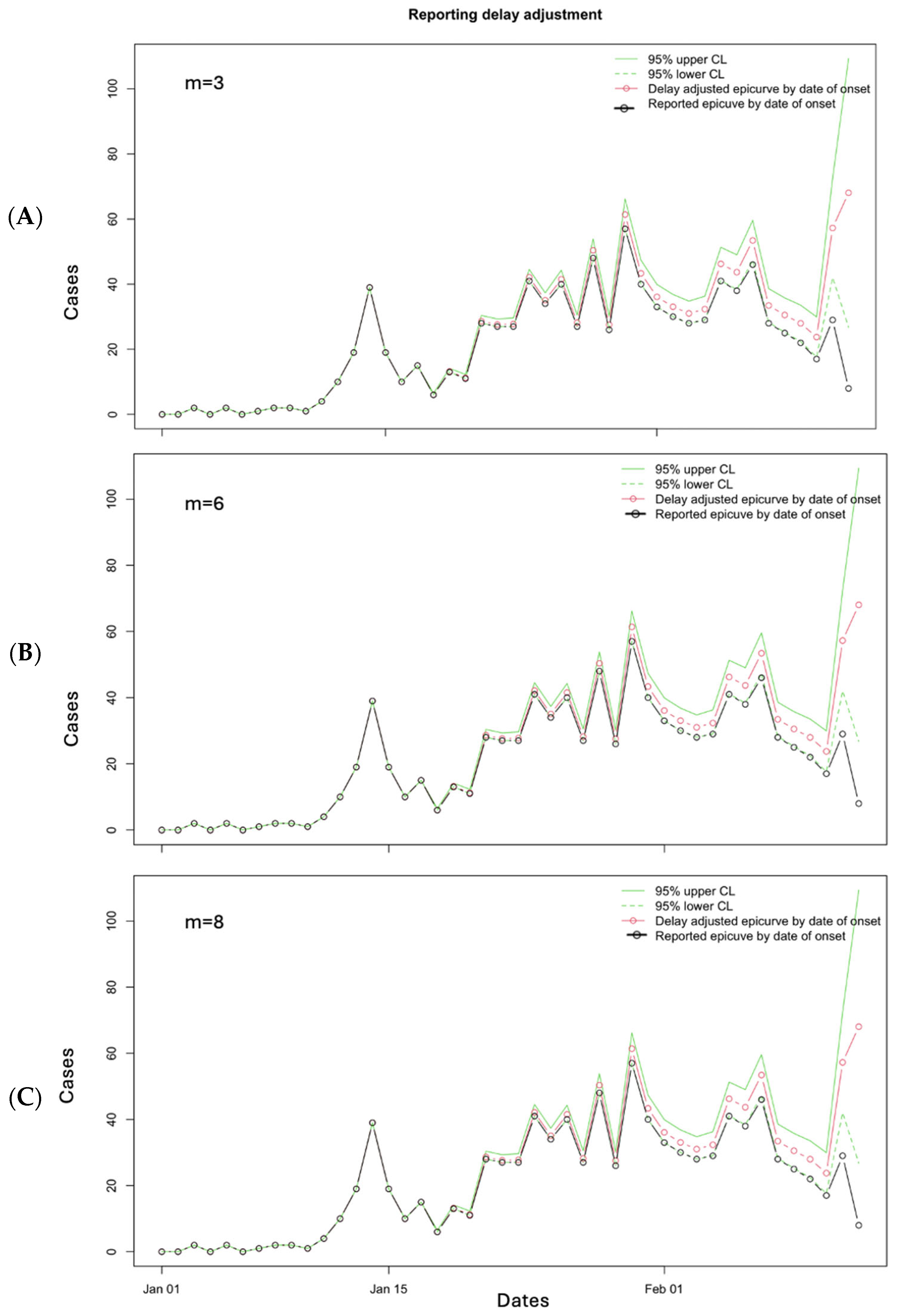

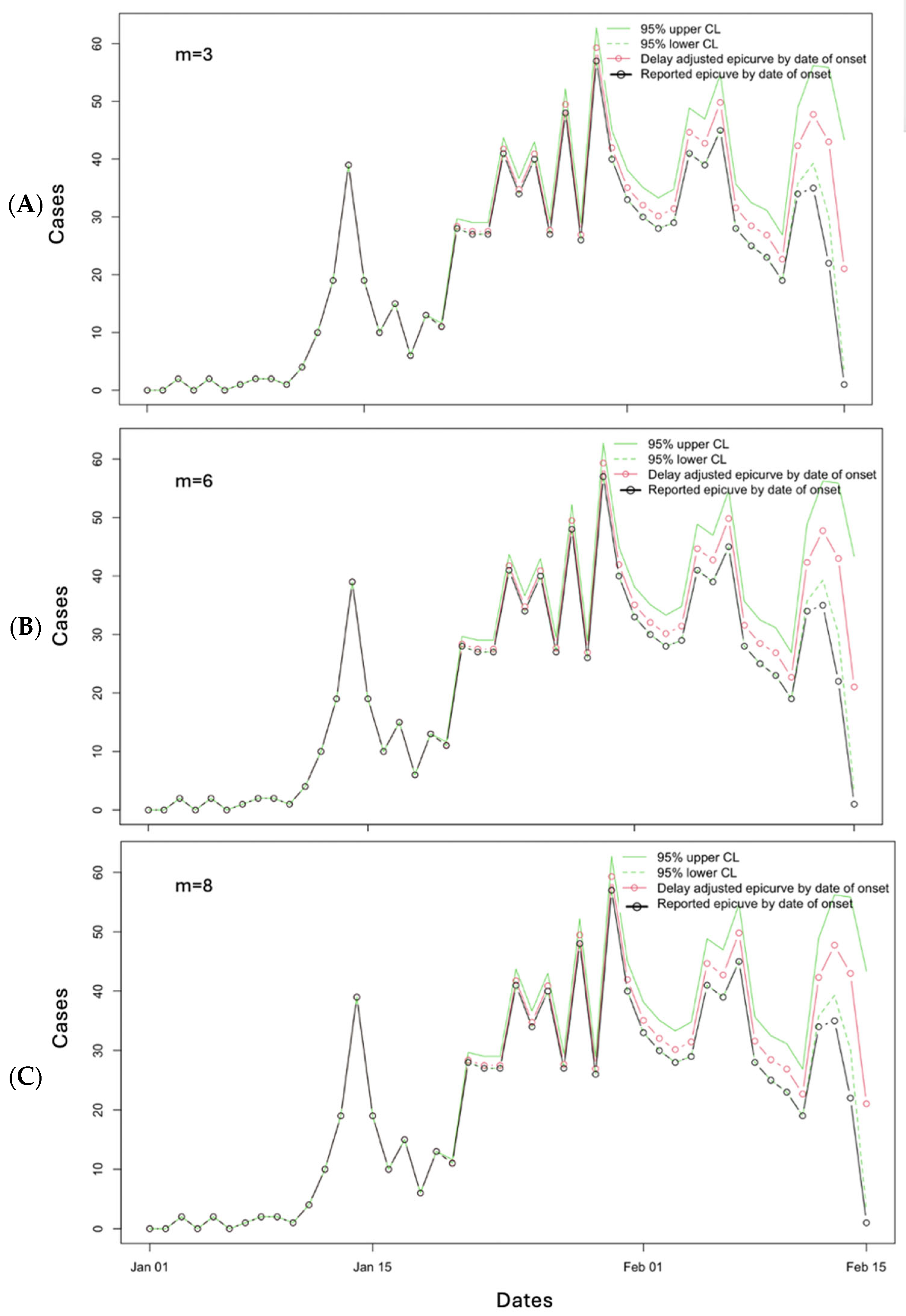

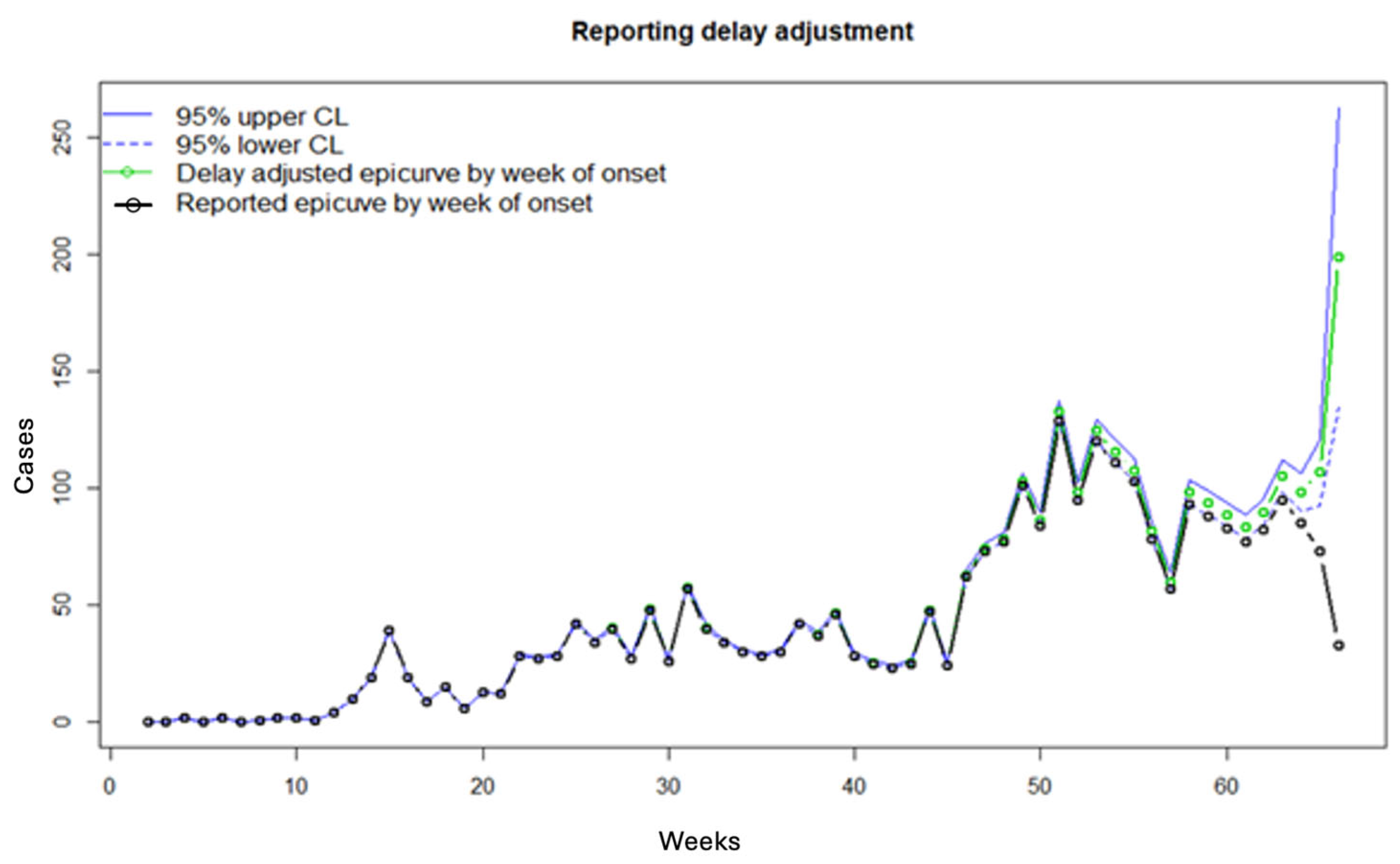

3.2. Results

3.3. Performance Metrics

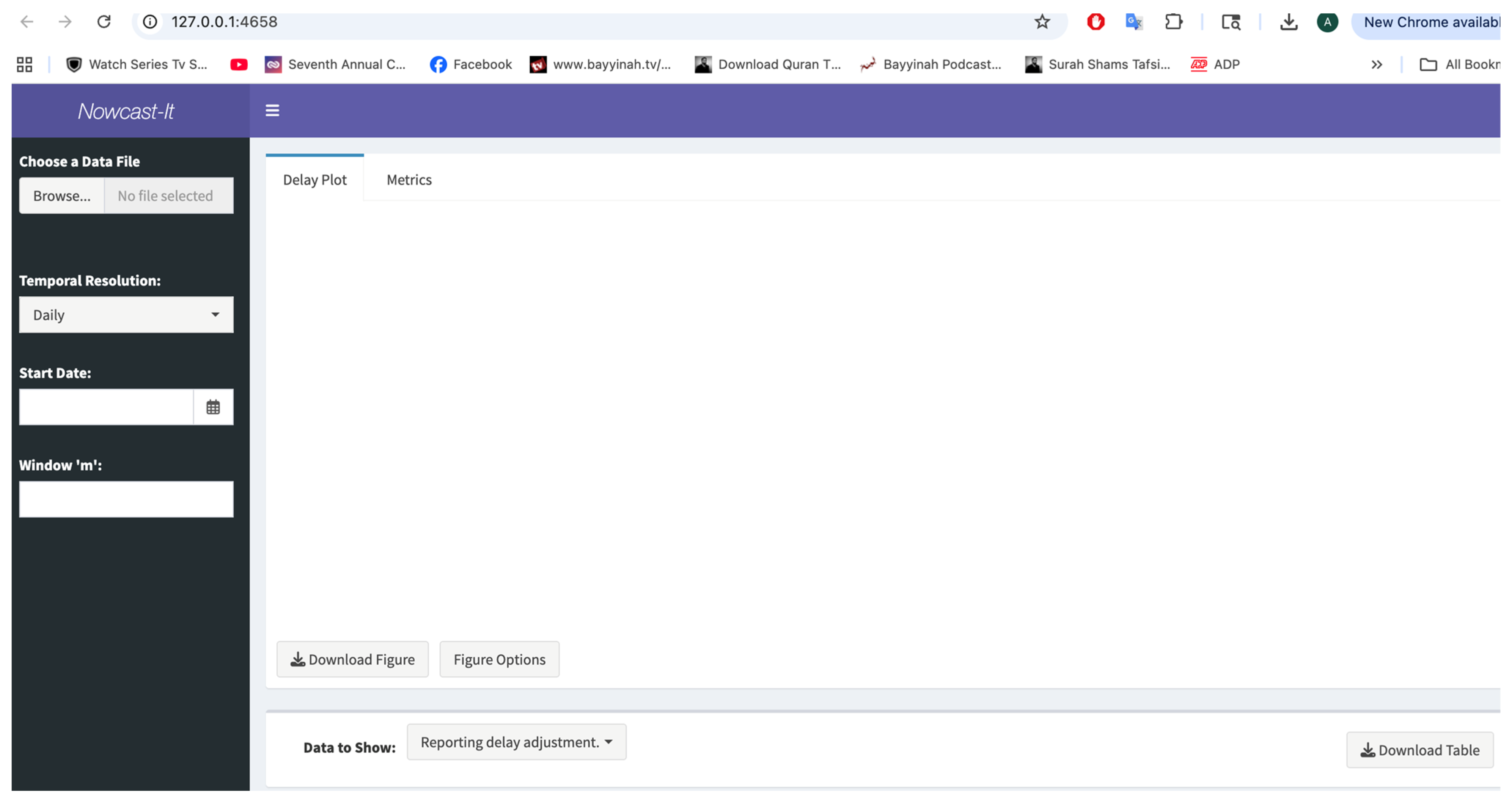

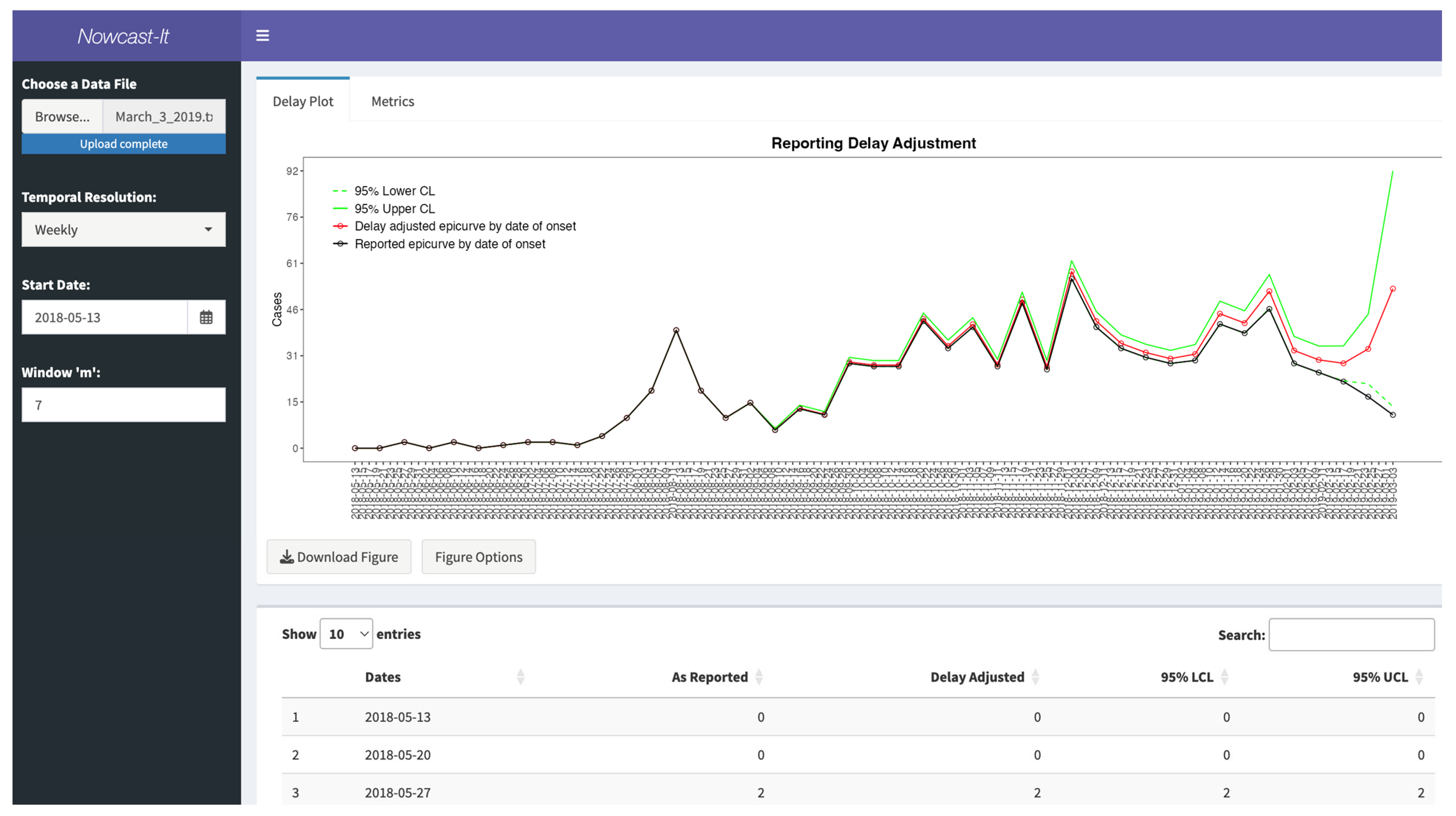

3.4. Shiny App in R

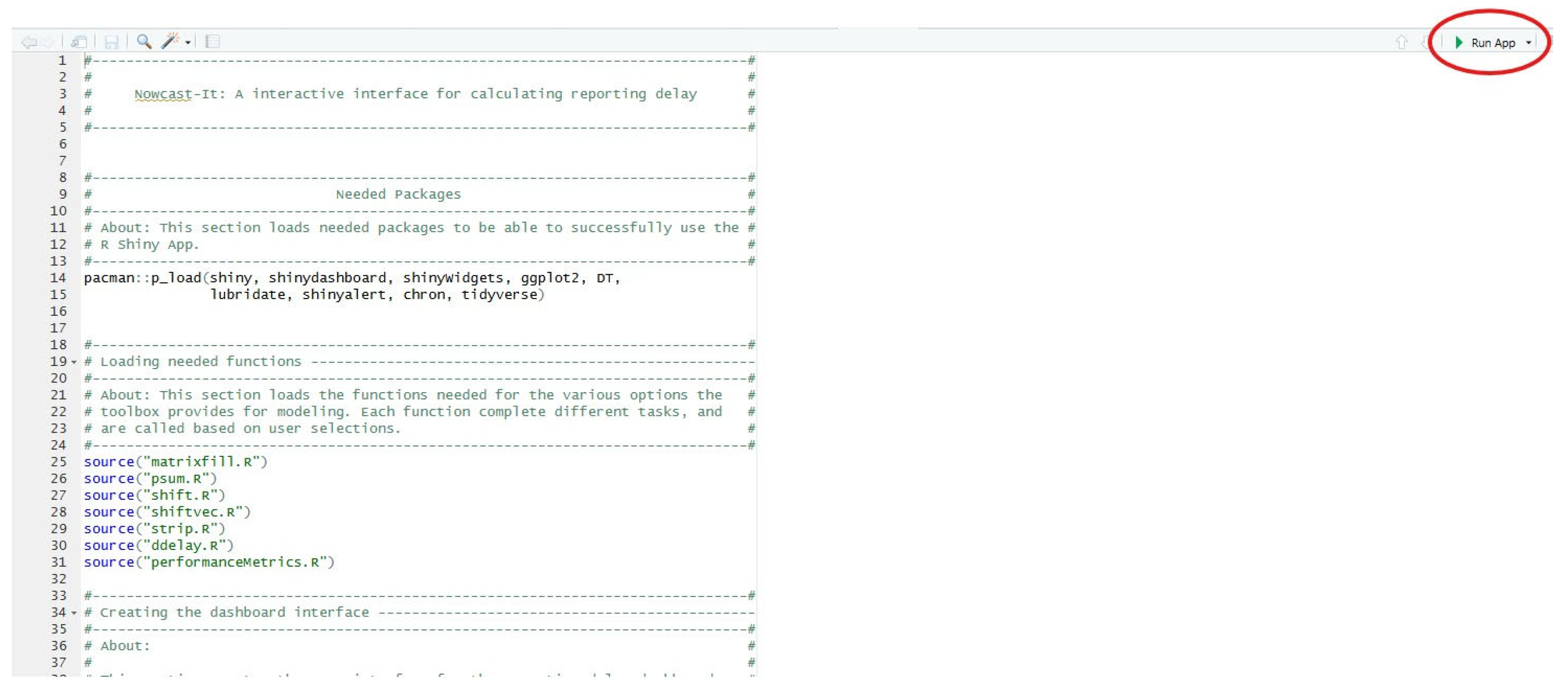

3.5. Installing and Loading the Shiny App

- Download the Nowcast-It Shiny folder containing the app and required functions from https://github.com/atariq2891/Reporting-delay-adjustment-code/tree/main (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Load the Nowcast-It Shiny project file in R-Studio.

- Open the ‘app.R’ file and click ‘Run App’.

3.6. Inputting the Data

3.7. User Specifications

3.8. Available Output

3.9. Performance Metrics

3.10. Limitations to Nowcasting Approach and How to Handle Them

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tariq, A.; Lee, Y.; Roosa, K.; Blumberg, S.; Yan, P.; Ma, S.; Chowell, G. Real-time monitoring the transmission potential of COVID-19 in Singapore, March 2020. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGough, S.F.; Johansson, M.A.; Lipsitch, M.; Menzies, N.A. Nowcasting by Bayesian Smoothing: A flexible, generalizable model for real-time epidemic tracking. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1007735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Kassteele, J.; Eilers, P.H.C.; Wallinga, J. Nowcasting the Number of New Symptomatic Cases During Infectious Disease Outbreaks Using Constrained P-spline Smoothing. Epidemiology 2019, 30, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, L.S.; Economou, T.; Gomes, M.F.C.; Villela, D.A.M.; Coelho, F.C.; Cruz, O.G.; Stoner, O.; Bailey, T.; Codeço, C.T. A modelling approach for correcting reporting delays in disease surveillance data. Stat. Med. 2019, 38, 4363–4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Roosa, K.; Mizumoto, K.; Chowell, G. Assessing reporting delays and the effective reproduction number: The Ebola epidemic in DRC, May 2018–January 2019. Epidemics 2019, 26, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesley, L.J.; Osthus, D.; Del Valle, S.Y. Addressing delayed case reporting in infectious disease forecast modeling. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2022, 18, e1010115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, E.; Tariq, A.; Choi, W.; Lee, Y.; Chowell, G. Transmission potential and severity of COVID-19 in South Korea. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 93, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, M.D.; Neuenschwander, B.E.; Zwahlen, M. Adjusting AIDS incidence for non-stationary reporting delays: A necessity for country comparisons. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 1998, 14, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, G.C. Claims Reserving in Non Life Insurance; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless, J.F. Adjustments for Reporting Delays and the Prediction of Occurred but Not Reported Events. Can. J. Stat. Rev. Can. Stat. 1994, 22, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookmeyer, R.; Liao, J.G. The analysis of delays in disease reporting: Methods and results for the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1990, 132, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalbfleisch, J.D.; Lawless, J.F. Estimating the incubation time distribution and expected number of cases of transfusion-associated acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Transfusion 1989, 29, 672–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Severson, E.O.; Ribeiro, R.M.; Castro, M. Noise Is Not Error: Detecting Parametric Heterogeneity Between Epidemiologic Time Series. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roosa, K.; Tariq, A.; Yan, P.; Hyman, J.M.; Chowell, G. Multi-model forecasts of the ongoing Ebola epidemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo, March–October 2019. J. R. Soc. Interface 2020, 17, 20200447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.T.; Wang, L.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Xu, X.K.; Du, Z.; Wu, Y.; Leung, G.M.; Cowling, B.J. Serial interval of SARS-CoV-2 was shortened over time by nonpharmaceutical interventions. Science 2020, 369, 1106–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charniga, K.; Park, S.W.; Akhmetzhanov, A.R.; Cori, A.; Dushoff, J.; Funk, S.; Gostic, K.M.; Linton, N.M.; Lison, A.; Overton, C.E.; et al. Best practices for estimating and reporting epidemiological delay distributions of infectious diseases. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2024, 20, e1012520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bracher, J.; Wolffram, D.; Deuschel, J.; Görgen, K.; Ketterer, J.L.; Ullrich, A.; Abbott, S.; Barbarossa, M.V.; Bertsimas, D.; Bhatia, S.; et al. A pre-registered short-term forecasting study of COVID-19 in Germany and Poland during the second wave. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Ebola Situation Reports: Democratic Republic of Congo. Available online: https://www.who.int/ebola/situation-reports/drc-2018/en/ (accessed on 12 January 2019).

| Function | Type | Role |

|---|---|---|

| datainpuut.txt | User | Reads a data file as input matrix. |

| ddelay.txt | User | Contains the algorithms of lawless based on reverse-time hazards and survival analysis. The input data is the matrix “mat”. There is a second choice, called “m”. This is to select the most recent “m” weeks (according to week of reporting) that we believe the reporting practice has been reasonably stable. |

| delay1.txt | Creates a temporary working matrix to be used in ddelay.txt function. | |

| matrixfill.txt | User | Creates the matrices for the right-truncated data. |

| psum.txt | User | Adds the components of the matrices. |

| shift.txt | User | Shifts the vector to the right or left. |

| shiftvec.txt | User | Creates the time-lagged matrix. Shifts the vector to the right or left. |

| strip.txt | User | If else function for the matrices. |

| Date of Situation Report | MAE | MSE | 95% PI Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 March, m = 7 | 1.66 | 15.13 | 95.34 |

| 3 March, m = 9 | 1.87 | 30.49 | 95.34 |

| 3 March, m = 11 | 2.26 | 46.56 | 95.34 |

| 10 March, m = 3 | 2.11 | 12.6 | 95.45 |

| 10 March, m = 6 | 1.98 | 30.8 | 95.45 |

| 10 March, m = 8 | 1.85 | 29.9 | 95.45 |

| 19 March, m = 3 | 2.17 | 90.02 | 86.9 |

| 19 March, m = 6 | 2.76 | 91.29 | 91.3 |

| 19 March, m = 8 | 2.37 | 69.68 | 91.3 |

| Required Software | R (≥4.3), R-Studio (2024.09.0 Build 375) |

|---|---|

| Compilation requirements 1 | pacman, shiny, shinydashboard, shinyWidgets, ggplot2, DT, lubridate, shinyalert, chron |

| Permanent link to repository | https://github.com/atariq2891/Reporting-delay-adjustment-code/tree/main/Shinyapp (accessed on 27 July 2025). |

| MAE | MSE | 95% PI Coverage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 March, m = 7 | 1.66 | 15.13 | 95.35 |

| 3 March, m = 9 | 1.88 | 30.5 | 95.35 |

| 3 March, m = 11 | 2.27 | 46.56 | 95.35 |

| 10 March, m = 3 | 2.11 | 12.64 | 95.45 |

| 10 March, m = 6 | 1.98 | 30.83 | 95.45 |

| 10 March, m = 8 | 1.85 | 29.96 | 95.45 |

| 19 March, m = 3 | 2.18 | 90.09 | 86.96 |

| 19 March, m = 6 | 2.77 | 91.29 | 91.30 |

| 19 March, m = 8 | 2.36 | 69.68 | 91.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tariq, A.; Yan, P.; Bleichrodt, A.; Chowell, G. Nowcast-It: A Practical Toolbox for Real-Time Adjustment of Reporting Delays in Epidemic Surveillance. Viruses 2025, 17, 1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121598

Tariq A, Yan P, Bleichrodt A, Chowell G. Nowcast-It: A Practical Toolbox for Real-Time Adjustment of Reporting Delays in Epidemic Surveillance. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121598

Chicago/Turabian StyleTariq, Amna, Ping Yan, Amanda Bleichrodt, and Gerardo Chowell. 2025. "Nowcast-It: A Practical Toolbox for Real-Time Adjustment of Reporting Delays in Epidemic Surveillance" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121598

APA StyleTariq, A., Yan, P., Bleichrodt, A., & Chowell, G. (2025). Nowcast-It: A Practical Toolbox for Real-Time Adjustment of Reporting Delays in Epidemic Surveillance. Viruses, 17(12), 1598. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121598