The First CRISPR-Based Therapeutic (SL_1.52) for African Swine Fever Is Effective in Swine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Viruses and Cell Culture

2.2. Design of the Guide Sequences for ASFV

2.3. Construction of SL_1.52 and Target Plasmids

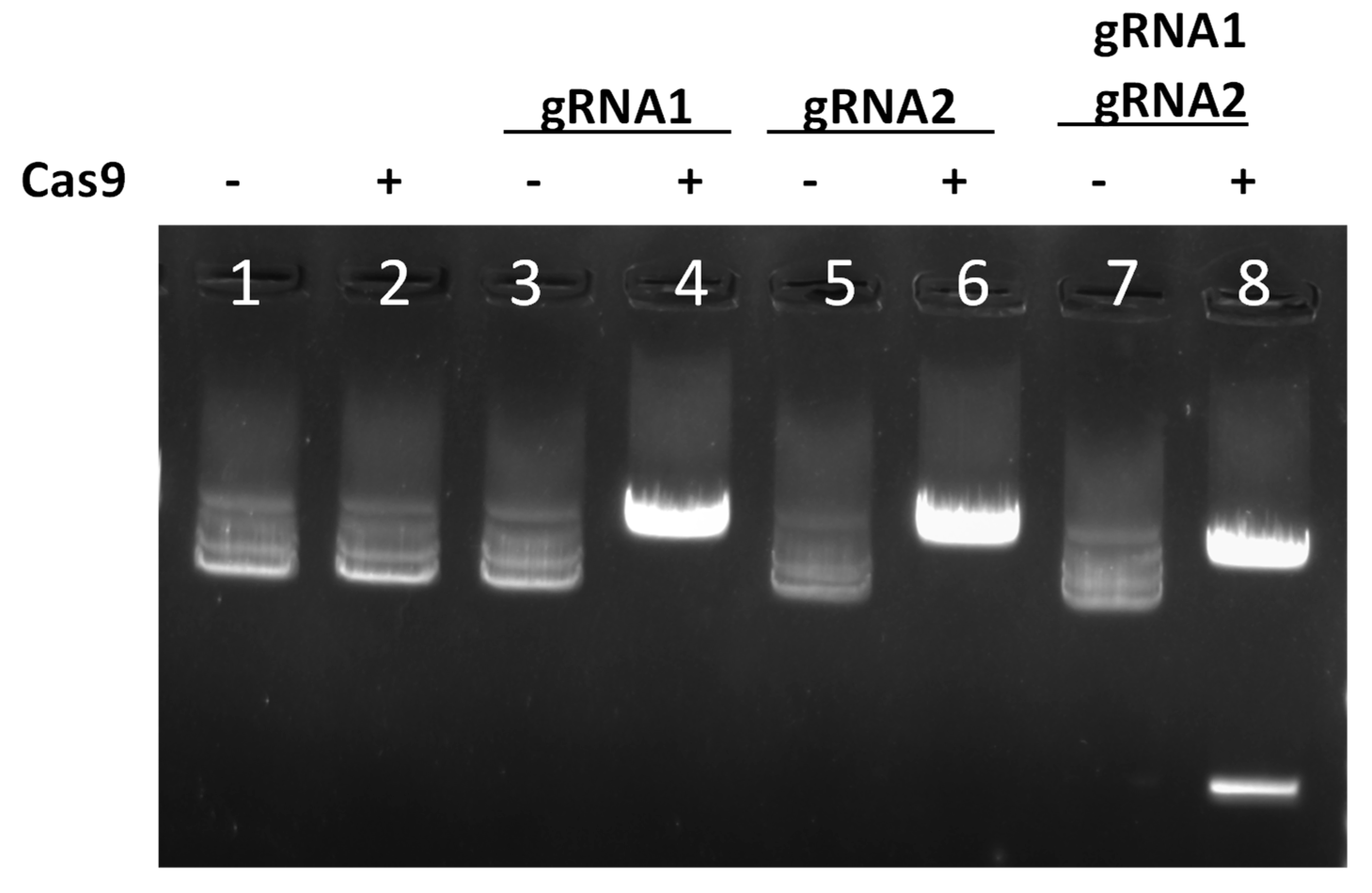

2.4. Biochemical Validation of Guide Sequences

2.5. In Vitro Cleavage of ASFV Target Sequences

2.6. Lipid Nano-Particle (LNP) Generation

2.7. Evaluation of SL_1.52 as a Thereputic in Swine

3. Results

3.1. SL_1.52 Construction and Design of Guides and Cas Molecules

3.2. Evaluation of SL_1.52 Cleavage In Vitro

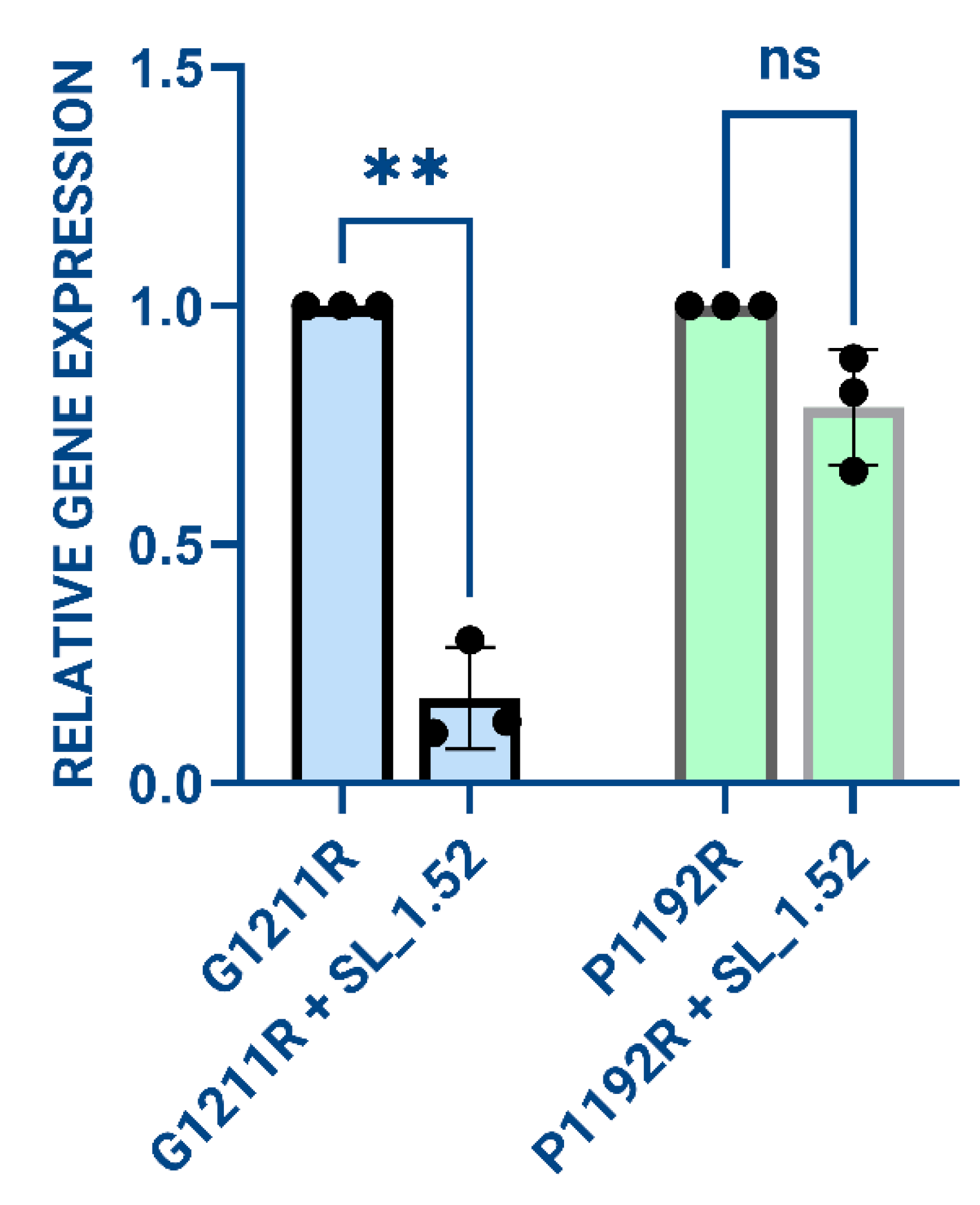

3.3. Evaluation of SL_1.52 Knockdown of Target Genes in Mammalian Cell Culture

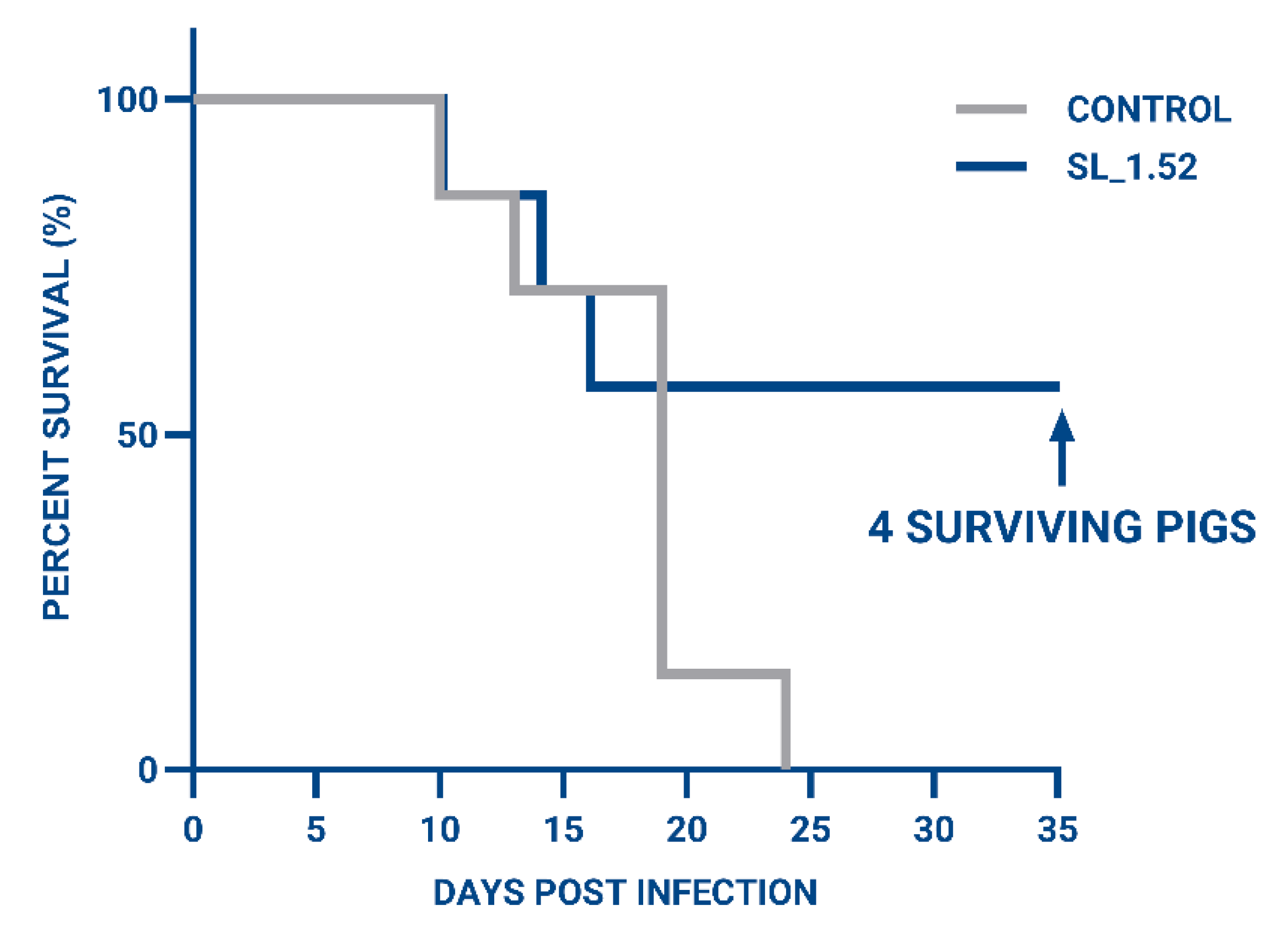

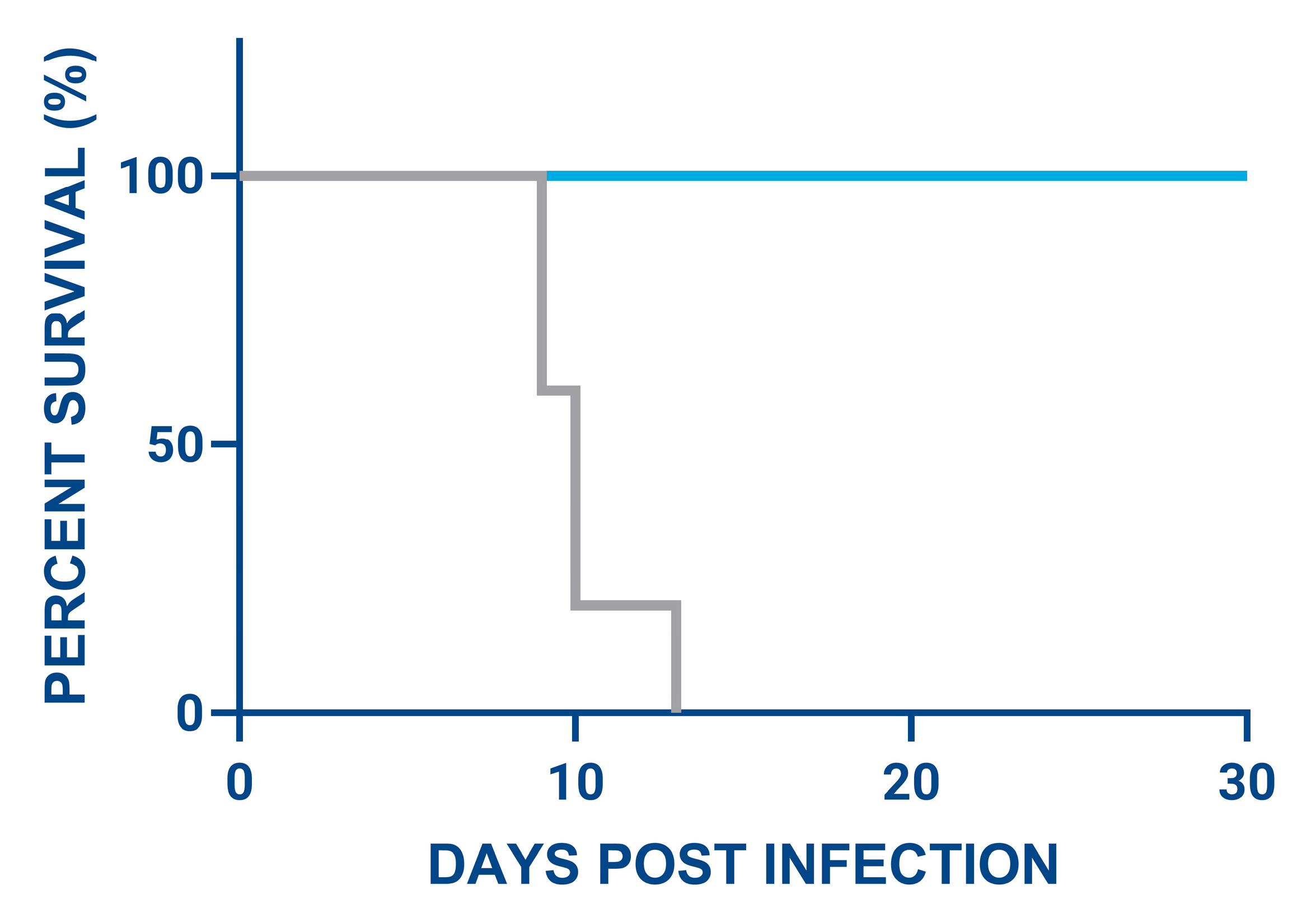

3.4. Evaluation of ASFV Virulence in Pigs Treated with ASFV SL_1.52 Targeting ASFV

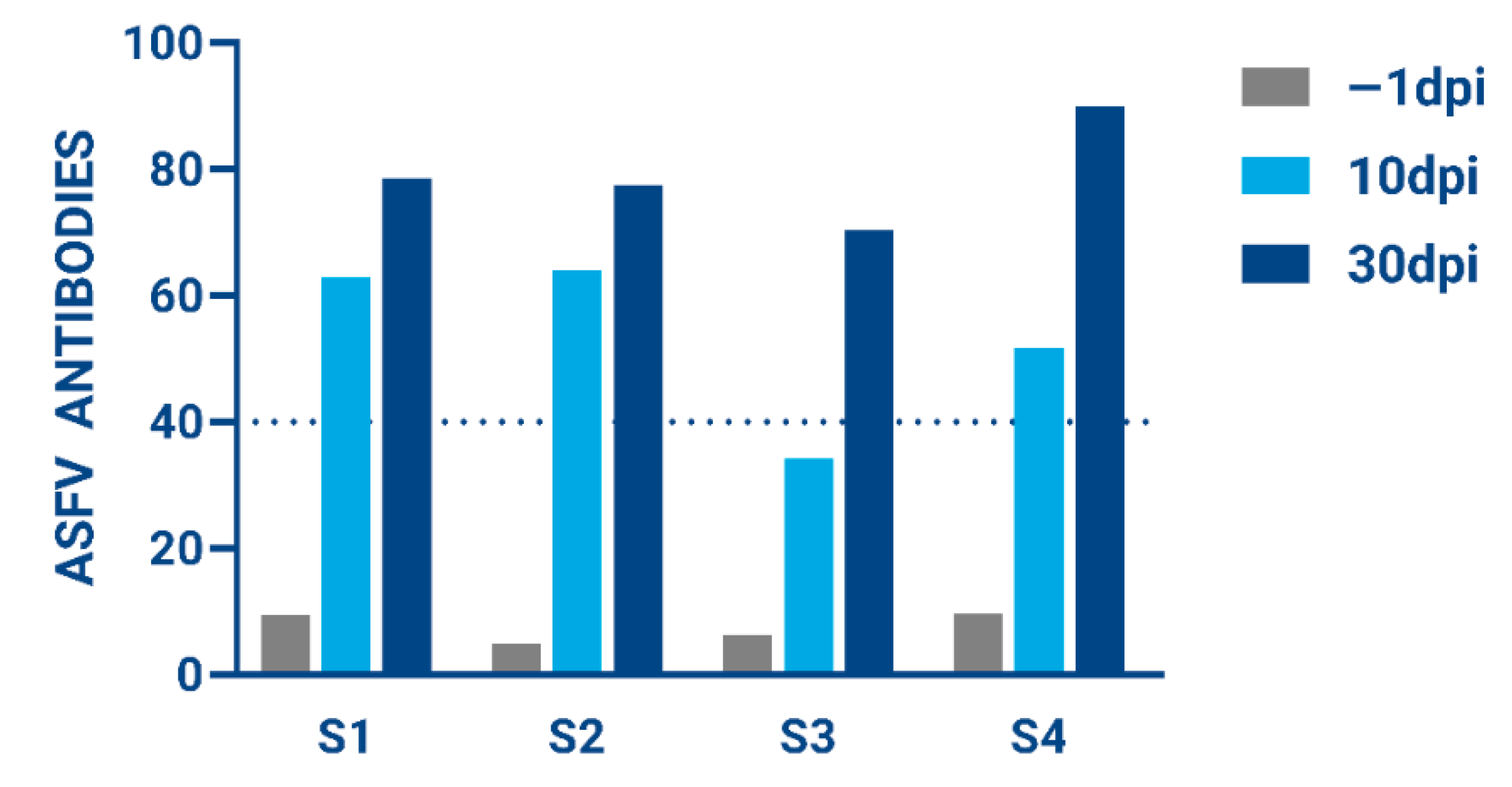

3.5. Evaluation of Immunity for Surviving Animals

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costard, S.; Wieland, B.; de Glanville, W.; Jori, F.; Rowlands, R.; Vosloo, W.; Roger, F.; Pfeiffer, D.U.; Dixon, L.K. African swine fever: How can global spread be prevented? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2683–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, R.E. On a form of swine fever occuring in British East Africa (Kenya Colony). J. Comp. Pathol. Ther. 1921, 34, 159–191, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.A.; Darby, A.C.; Da Silva, M.; Upton, C.; Radford, A.D.; Dixon, L.K. Genomic analysis of highly virulent Georgia 2007/1 isolate of African swine fever virus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, W.; Moreno, C.; Duran, U.; Henao, N.; Bencosme, M.; Lora, P.; Reyes, R.; Nunez, R.; De Gracia, A.; Perez, A.M. African swine fever in the Dominican Republic. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2021, 68, 3018–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean-Pierre, R.P.; Hagerman, A.D.; Rich, K.M. An analysis of African Swine Fever consequences on rural economies and smallholder swine producers in Haiti. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 960344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulman, E.R.; Delhon, G.A.; Ku, B.K.; Rock, D.L. African Swine Fever Virus. In Lesser Known Large dsDNA Viruses; Etten, V., Ed.; Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 328, pp. 43–87. [Google Scholar]

- Spinard, E.; Azzinaro, P.; Rai, A.; Espinoza, N.; Ramirez-Medina, E.; Valladares, A.; Borca, M.V.; Gladue, D.P. Complete Structural Predictions of the Proteome of African Swine Fever Virus Strain Georgia 2007. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2022, 11, e0088122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladue, D.P.; Borca, M.V. Recombinant ASF Live Attenuated Virus Strains as Experimental Vaccine Candidates. Viruses 2022, 14, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, V.K.; Grau, F.R.; Mayr, G.A.; Sturgill Samayoa, T.L.; Dodd, K.A.; Barrette, R.W. Rapid Sequence-Based Characterization of African Swine Fever Virus by Use of the Oxford Nanopore MinION Sequence Sensing Device and a Companion Analysis Software Tool. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019, 58, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanez, R.J.; Moya, A.; Vinuela, E.; Domingo, E. Repetitive nucleotide sequencing of a dispensable DNA segment in a clonal population of African swine fever virus. Virus Res. 1991, 20, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Hu, Y.; Zheng, D.; Sun, C.; Song, F.; et al. Generation of High-Quality African Swine Fever Virus Complete Genome from Field Samples by Next-Generation Sequencing. Viruses 2024, 16, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinard, E.; Dinhobl, M.; Erdelyan, C.N.G.; O’Dwyer, J.; Fenster, J.; Birtley, H.; Tesler, N.; Calvelage, S.; Leijon, M.; Steinaa, L.; et al. A Standardized Pipeline for Assembly and Annotation of African Swine Fever Virus Genome. Viruses 2024, 16, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinhobl, M.; Spinard, E.; Tesler, N.; Birtley, H.; Signore, A.; Ambagala, A.; Masembe, C.; Borca, M.V.; Gladue, D.P. Reclassification of ASFV into 7 Biotypes Using Unsupervised Machine Learning. Viruses 2023, 16, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteagudo, P.L.; Lacasta, A.; Lopez, E.; Bosch, L.; Collado, J.; Pina-Pedrero, S.; Correa-Fiz, F.; Accensi, F.; Navas, M.J.; Vidal, E.; et al. BA71DeltaCD2: A New Recombinant Live Attenuated African Swine Fever Virus with Cross-Protective Capabilities. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diep, N.V.; Duc, N.V.; Ngoc, N.T.; Dang, V.X.; Tiep, T.N.; Nguyen, V.D.; Than, T.T.; Maydaniuk, D.; Goonewardene, K.; Ambagala, A.; et al. Genotype II Live-Attenuated ASFV Vaccine Strains Unable to Completely Protect Pigs against the Emerging Recombinant ASFV Genotype I/II Strain in Vietnam. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenheft, B.; Sternberg, S.H.; Doudna, J.A. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature 2012, 482, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terns, M.P.; Terns, R.M. CRISPR-based adaptive immune systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2011, 14, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaya, D.; Davison, M.; Barrangou, R. CRISPR-Cas systems in bacteria and archaea: Versatile small RNAs for adaptive defense and regulation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011, 45, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.T. Approval of the First CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Therapy for Sickle Cell Disease. Clin. Chem. 2024, 70, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledford, H. Geneticists enlist engineered virus and CRISPR to battle citrus disease. Nature 2017, 545, 277–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, D.M.; Vajravelu, L.K.; Thulukanam, J.; Paneerselvam, V.; Vimala, P.B.; Lathakumari, R.H. Tackling hepatitis B Virus with CRISPR/Cas9: Advances, challenges, and delivery strategies. Virus Genes 2024, 60, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, S.; Ogawa, H.; Katoh, H.; Honda, T. Suppression of Borna Disease Virus Replication during Its Persistent Infection Using the CRISPR/Cas13b System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuai, L.; Sun, J.; Peng, Q.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, B.; Liu, S.; Bi, Y.; Shi, Y. Cryo-EM structure of DNA polymerase of African swine fever virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, 10717–10729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borca, M.V.; Berggren, K.A.; Ramirez-Medina, E.; Vuono, E.A.; Gladue, D.P. CRISPR/Cas Gene Editing of a Large DNA Virus: African Swine Fever Virus. Bio-Protoc. 2018, 8, e2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Hyg. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Doench, J.G.; Fusi, N.; Sullender, M.; Hegde, M.; Vaimberg, E.W.; Donovan, K.F.; Smith, I.; Tothova, Z.; Wilen, C.; Orchard, R.; et al. Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ricci-Tam, C.; Hager, E.R.; Sgro, A.E. Self-cleaving peptides for expression of multiple genes in Dictyostelium discoideum. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; He, X.; Zhao, T.; Gu, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Yang, F.; Tu, M.; Tang, L.; et al. Engineering the Direct Repeat Sequence of crRNA for Optimization of FnCpf1-Mediated Genome Editing in Human Cells. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 2650–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, L.; Witzigmann, D.; Kulkarni, J.A.; Verbeke, R.; Kersten, G.; Jiskoot, W.; Crommelin, D.J.A. mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: Structure and stability. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 601, 120586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoes, M.; Freitas, F.B.; Leitao, A.; Martins, C.; Ferreira, F. African swine fever virus replication events and cell nucleus: New insights and perspectives. Virus Res. 2019, 270, 197667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.M.; Garcia-Escudero, R.; Salas, M.L.; Andres, G. African swine fever virus structural protein p54 is essential for the recruitment of envelope precursors to assembly sites. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 4299–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubner, A.; Petersen, B.; Keil, G.M.; Niemann, H.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Fuchs, W. Efficient inhibition of African swine fever virus replication by CRISPR/Cas9 targeting of the viral p30 gene (CP204L). Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, M.; Rodriguez-Carino, C.; Perez, M.; Gallardo, C.; Rodriguez, J.M.; Salas, M.L.; Rodriguez, F. Disruption of nuclear organization during the initial phase of African swine fever virus infection. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 8263–8269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xu, L.; Gao, Y.; Dou, H.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, X.; He, X.; Tian, Z.; Song, L.; Mo, G.; et al. Testing multiplexed anti-ASFV CRISPR-Cas9 in reducing African swine fever virus. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0216423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| gRNA1 | gattgttgcacgggagaacc |

| gRNA2 | tttaacaatcgtctcgtgga |

| Animal | Days Post Infection | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | 35 | |

| Untreated-1 | N | 34.16 | 28.00 | 22.68 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Untreated-2 | N | N | 32.40 | 26.99 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Untreated-3 | N | N | 23.84 | 29.16 | 34.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Untreated-4 | N | 36.71 | 34.75 | 32.94 | 36.68 | N | 36.57 | - | - |

| Untreated-5 | N | 36.22 | 36.75 | 31.30 | 30.98 | - | - | - | - |

| Untreated-6 | N | 33.09 | 34.05 | 31.81 | 29.03 | - | - | - | - |

| Untreated-7 | N | 41.42 | N | 30.94 | 34.44 | - | - | - | - |

| SL_1.52-8 | N | N | 35.88 | 38.82 | N | 33.17 | 34.51 | 41.38 | N |

| SL_1.52-9 | N | N | N | 41.89 | - | - | - | - | - |

| SL_1.52-10 | N | 35.74 | 29.32 | 38.05 | 34.07 | 38.47 | N | N | N |

| SL_1.52-11 | N | 40.18 | 36.34 | 37.96 | 28.84 | N | N | N | N |

| SL_1.52-12 | N | N | N | 38.30 | 34.88 | 33.17 | 33.58 | N | N |

| SL_1.52-13 | N | 38.44 | 38.59 | 36.51 | - | - | - | - | - |

| SL_1.52-14 | N | N | 32.27 | 34.73 | 25.91 | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Verma, N.; O’Mahony, A.; Mohammad, R.; Keiser, D.; Mosman, C.W.; Holden, D.; Starr, K.; Bauer, J.; Bauer, B.; Suntisukwattana, R.; et al. The First CRISPR-Based Therapeutic (SL_1.52) for African Swine Fever Is Effective in Swine. Viruses 2025, 17, 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111504

Verma N, O’Mahony A, Mohammad R, Keiser D, Mosman CW, Holden D, Starr K, Bauer J, Bauer B, Suntisukwattana R, et al. The First CRISPR-Based Therapeutic (SL_1.52) for African Swine Fever Is Effective in Swine. Viruses. 2025; 17(11):1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111504

Chicago/Turabian StyleVerma, Naveen, Alison O’Mahony, Roky Mohammad, Dylan Keiser, Craig W. Mosman, Deric Holden, Kristin Starr, Jared Bauer, Bradley Bauer, Roypim Suntisukwattana, and et al. 2025. "The First CRISPR-Based Therapeutic (SL_1.52) for African Swine Fever Is Effective in Swine" Viruses 17, no. 11: 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111504

APA StyleVerma, N., O’Mahony, A., Mohammad, R., Keiser, D., Mosman, C. W., Holden, D., Starr, K., Bauer, J., Bauer, B., Suntisukwattana, R., Atthaapa, W., Tantituvanont, A., Nilubol, D., & Gladue, D. P. (2025). The First CRISPR-Based Therapeutic (SL_1.52) for African Swine Fever Is Effective in Swine. Viruses, 17(11), 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111504