Effectiveness and Safety of Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide in People Living with HIV Aged 50 Years and Older: A Retrospective Analysis of Naïve and Treatment-Experienced Individuals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

- Naïve Cohort: Patients who were ART-naïve and started B/F/TAF as their first-ever HIV treatment.

- Experienced Cohort: Patients who were on a previous antiretroviral regimen for at least 3 months prior to switching to B/F/TAF. Virologic suppression at the time of switch was not required.

2.2. Study Objectives and Endpoints

- Immunological efficacy evaluated by change from baseline to M12 and M24 in CD4+ T-cell count and the CD4+/CD8+ ratio.

- Metabolic Safety evaluated by change from baseline to M12 and M24 in fasting glucose and the Triglyceride-Glucose (TyG) Index. The TyG index is a simple, low-cost biochemical marker of insulin resistance, calculated using the formula: Ln [fasting triglycerides (mg/dL) × fasting glucose (mg/dL)/2] [10].

- Hepatic Safety evaluated by change from baseline to M12 and M24 in liver enzymes (AST, ALT) and the Fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) index. The FIB-4 is a non-invasive calculation using a patient’s age, AST, ALT, and platelet count to estimate liver fibrosis, or scarring [11]. Hepatic steatosis and fibrosis were also evaluated by change from baseline to M12 in liver stiffness (kPa) and Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP) score, assessed by transient elastography (FibroScan) in a subset of experienced patients.

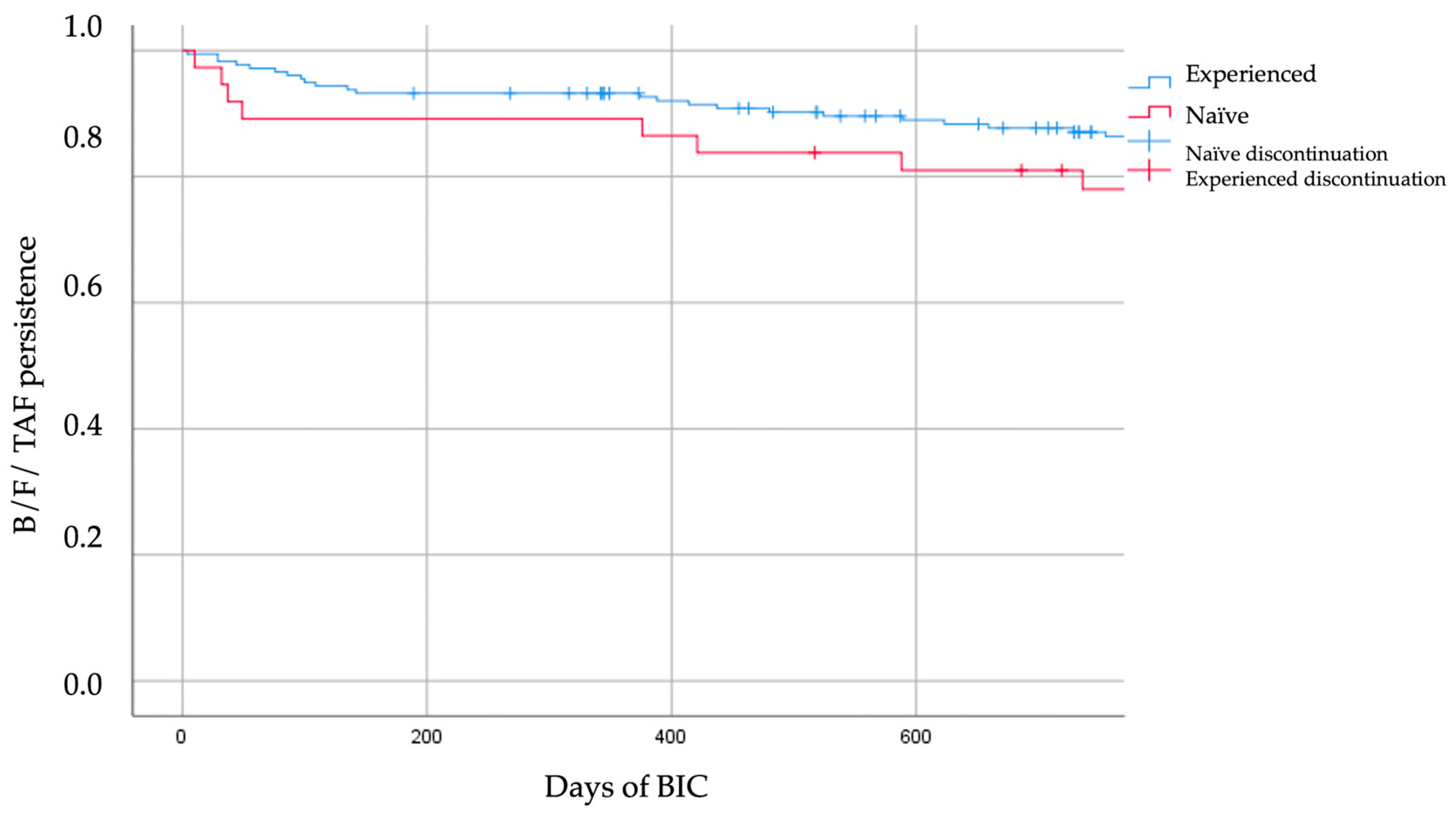

- Treatment durability and tolerability profile. Long-term treatment durability, defined as the time from initiation to discontinuation of B/F/TAF, was evaluated using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis over the entire study period, and tolerability was concurrently assessed, with specific reasons for discontinuation described.

2.3. Data Collection and Variables

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Handling of Missing Data

3. Results

3.1. Patient Population and Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Effectiveness Outcomes

3.3. Immunological Outcome

3.4. Metabolic and Hepatic Outcomes

3.5. Treatment Durability, Safety, and Adverse Events

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3TC | lamivudine |

| ART | antiretroviral therapy |

| B/F/TAF | bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide |

| CAB-RPV LA | Cabotegravir–rilpivirine therapy |

| CAP | Controlled Attenuation Parameter |

| DDIs | drug–drug interactions |

| DTG | dolutegravir |

| FIB-4 | Fibrosis-4 index |

| HBsAg | Hepatitis B surface antigen |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HIV | human immunodeficiency virus |

| PLWH | People living with HIV |

| TyG | Triglyceride-Glucose index |

References

- Wing, E.J. HIV and aging. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 53, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Lancet Healthy Longevity. Ageing with HIV. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022, 3, e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- High, K.P.; Brennan-Ing, M.; Clifford, D.B.; Cohen, M.H.; Currier, J.; Deeks, S.G.; Deren, S.; Effros, R.B.; Gebo, K.; Goronzy, J.J.; et al. HIV and aging: State of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2012, 60 (Suppl. S1), S1–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pipitò, L.; Zinna, G.; Trizzino, M.; Gioè, C.; Tolomeo, M.; Di Carlo, P.; Colomba, C.; Gibaldi, L.; Iaria, C.; Almasio, P.; et al. Causes of hospitalization and predictors of in-hospital mortality among people living with HIV in Sicily-Italy between 2010 and 2021. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 1703–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasia, A.; Mazzucco, W.; Pipitò, L.; Fruscione, S.; Gaudiano, R.; Trizzino, M.; Zarcone, M.; Cascio, A. Malignancies in people living with HIV: A 25-years observational study from a tertiary hospital in Italy. J. Infect. Public Health 2025, 18, 102661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piselli, P.; Tavelli, A.; Cimaglia, C.; Muccini, C.; Bandera, A.; Marchetti, G.C.; Torti, C.; Mazzotta, V.; Pipitò, L.; Caioli, A.; et al. Cancer incidence in people with HIV in Italy: Comparison of the ICONA COHORT with general population data. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 157, 1142–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guaraldi, G.; Milic, J.; Mussini, C. Aging with HIV. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 2019, 16, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiolo, F.; Rizzardini, G.; Molina, J.; Pulido, F.; De Wit, S.; Vandekerckhove, L.; Berenguer, J.; D’Antoni, M.L.; Blair, C.; Chuck, S.K.; et al. Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in older individuals with HIV: Results of a 96-week, phase 3b, open-label, switch trial in virologically suppressed people ≥ 65 years of age. HIV Med. 2022, 24, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaro, A.; Cacciola, E.G.; Borrazzo, C.; Innocenti, G.P.; Cavallari, E.N.; Mezzaroma, I.; Falciano, M.; Fimiani, C.; Mastroianni, C.M.; Ceccarelli, G.; et al. Switching to a Bictegravir Single Tablet Regimen in Elderly People Living with HIV-1: Data Analysis from the BICTEL Cohort. Diagnostics 2021, 12, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, V.K.R.; Satheesh, P.; Shenoy, M.T.; Kalra, S. Triglyceride Glucose (TyG) Index: A surrogate biomarker of insulin resistance. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2022, 72, 986–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallet, V.; Parlati, L.; Vallet-Pichard, A.; Terris, B.; Tsochatzis, E.; Sogni, P.; Pol, S. L’index FIB-4 pour faire le diagnostic de fibrose hépatique avancée au cours de la stéatose hépatique [FIB-4 index to rule-out advanced liver fibrosis in NAFLD patients]. La Presse Médicale 2019, 48, 1484–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calza, L.; Giglia, M.; Zuppiroli, A.; Cretella, S.; Vitale, S.; Appolloni, L.; Viale, P. Decrease in drug-drug interactions between antiretroviral drugs and concomitant therapies in older people living with HIV-1 switching to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide. New Microbiol. 2025, 48, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ikwuagwu, J.O.; Tran, V.; Tran, N.A.K. Drug-drug interactions of Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors among older people living with HIV: Interazioni farmacologiche degli inibitori delle integrase tra le persone anziane che vivono con HIV. J HIV Ageing 2022, 7, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kawashima, A.; Trung, H.T.; Watanabe, K.; Takano, M.; Deguchi, Y.; Kinoshita, M.; Uemura, H.; Yanagawa, Y.; Gatanaga, H.; Kikuchi, Y.; et al. Pharmacokinetics of Bictegravir in Older Japanese People Living with HIV-1. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0507922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ekobena, P.; Briki, M.; Dao, K.; Marzolini, C.; Andre, P.; Buclin, T.; Cavassini, M.; Guidi, M.; Thoueille, P.; Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Population pharmacokinetics of bictegravir in real-world people with HIV. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 2782–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stader, F.; Courlet, P.; Decosterd, L.A.; Battegay, M.; Marzolini, C. Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling Combined with Swiss HIV Cohort Study Data Supports No Dose Adjustment of Bictegravir in Elderly Individuals Living With HIV. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 109, 1025–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lê, M.P.; Allavena, C.; Joly, V.; Assoumou, L.; Isernia, V.; Ajana, F.; Neau, D.; Descamps, D.; Charpentier, C.; Benalycherif, A.; et al. Switch to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in people living with HIV aged 65 years or older: BICOLDER study—IMEA IMEA 057. J. Infect. Public Health 2025, 18, 102946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolle, C.-P.; Nguyen, V.; Patel, K.; Cruz, D.; DeJesus, E.; Hinestrosa, F. Real-world efficacy and safety of switching to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in older people living with HIV. Medicine 2021, 100, e27330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kityo, C.M.; Gupta, S.K.; Kumar, P.N.; Weinberg, A.R.; Gandhi-Patel, B.; Liu, H.; Hindman, J.T.; Rockstroh, J.K. Efficacy and safety of B/F/TAF in treatment-naïve and virologically suppressed people with HIV ≥ 50 years of age: Integrated analysis from six phase 3 clinical trials. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gidari, A.; Benedetti, S.; Tordi, S.; Zoffoli, A.; Altobelli, D.; Schiaroli, E.; De Socio, G.V.; Francisci, D. Bictegravir/Tenofovir Alafenamide/Emtricitabine: A Real-Life Experience in People Living with HIV (PLWH). Infect. Dis. Rep. 2023, 15, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vito, A.; Tavelli, A.; Cozzi-Lepri, A.; Giacomelli, A.; Rossotti, R.; Ponta, G.; Bobbio, N.; Ianniello, A.; Cingolani, A.; Madeddu, G.; et al. Safety and effectiveness of switch to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide following dual regimen therapy in people with HIV: Insights from the Icona cohort. HIV Med. 2025, 26, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Deeks, E.D. Darunavir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide: A Review in HIV-1 Infection. Drugs 2018, 78, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trizzino, M.; Gaudiano, R.; Arena, D.M.; Pipitò, L.; Gioè, C.; Cascio, A. Switching to Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide Fumarate Regimen and Its Effect on Liver Steatosis Assessed by Fibroscan. Viruses 2025, 17, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eron, J.J.; Ramgopal, M.; Osiyemi, O.; Mckellar, M.; Slim, J.; DeJesus, E.; Arora, P.; Blair, C.; Hindman, J.T.; Wilkin, A. Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in adults with HIV-1 and end-stage kidney disease on chronic haemodialysis. HIV Med. 2024, 26, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Adachi, E.; Yokomaku, Y.; Watanabe, D.; Gatanaga, H.; Oka, S.; Shirasaka, T.; Wakatabe, R.; Chamay, N.; Sutton, K.; Sutherland-Phillips, D.; et al. Efficacy and safety of switching to long-acting cabotegravir + rilpivirine versus continuing bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in Japanese participants: 12-month results from the phase 3b randomized SOLAR trial. J. Infect. Chemother. 2025, 31, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mussini, C.; Cazanave, C.; Adachi, E.; Eu, B.; Alonso, M.M.; Crofoot, G.; Chounta, V.; Kolobova, I.; Sutton, K.; Sutherland-Phillips, D.; et al. Improvements in Patient-Reported Outcomes After 12 Months of Maintenance Therapy with Cabotegravir + Rilpivirine Long-Acting Compared with Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide in the Phase 3b SOLAR Study. AIDS Behav. 2024, 29, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trizzino, M.; Pipitò, L.; Salvo, P.F.; Zimmerhofer, F.; Cicero, A.; Baldin, G.; Conti, C.; Gioè, C.; Di Giambenedetto, S.; Cascio, A. Real-World Experience with Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir/Rilpivirine in HIV Patients with Unsuppressed Viral Load. Viruses 2025, 17, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Characteristic | Overall Population (n = 214) | Naïve Cohort (n = 37) | Experienced Cohort (n = 177) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 60.6 ± 7.3 | 58.6 ± 6.7 | 61.1 ± 7.4 |

| Male Sex, n (%) | 160 (74.8%) | 30 (81.1%) | 130 (73.4%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 196 (91.6%) | 33 (89.2%) | 163 (92.1%) |

| African | 18 (8.4%) | 4 (10.8%) | 14 (7.9%) |

| HIV-Related Factors | |||

| HIV History, years, mean ± SD | * | N/A | 20.9 ± 9.6 |

| HCV Seropositivity, n/N (%) | 50/214 (23.4%) | 6/37 (16.2%) | 44/177 (24.9%) |

| HBsAg Seropositivity, n/N (%) | 14/214 (6.5%) | 3/37 (8.1%) | 11/177 (6.2%) |

| Comorbidities, n/N (%) | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 93/200 (46.5%) | 7/32 (21.9%) | 86/168 (51.2%) |

| Hypertension | 86/210 (41.0%) | 11/35 (31.4%) | 75/175 (42.9%) |

| Osteoporosis | 43/198 (21.7%) | 0/32 (0.0%) | 43/166 (25.9%) |

| Obesity | 27/199 (13.6%) | 6/33 (18.2%) | 21/166 (12.7%) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 20/208 (9.6%) | 2/34 (5.9%) | 18/174 (10.3%) |

| Oncological Disease | 27/199 (13.6%) | 2/32 (6.3%) | 25/167 (15.0%) |

| COPD | 10/199 (5.0%) | 0/32 (0.0%) | 10/167 (6.0%) |

| Current Smoking | 95/209 (45.5%) | 15/36 (41.7%) | 80/173 (46.2%) |

| Multi-morbidity (≥3 NCDs) | 123/198 (62.1%) | 18/32 (56.3%) | 105/166 (63.3%) |

| Polypharmacy (≥5 meds) | 36/124 (29.0%) | 5/13 (38.5%) | 31/111 (27.9%) |

| Treatment Data | |||

| Years on B/F/TAF, median [IQR] | 3.43 [2.37–5.38] (n = 173) | 3.28 [2.69–4.58] (n = 27) | 3.44 [2.22–5.46] (n = 146) |

| Discontinued B/F/TAF, n (%) | 41 (19.2%) | 10 (27.0%) | 31 (17.5%) |

| Timepoint | Naïve Cohort (n = 27) | Experienced Cohort (n = 146) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Pre-switch) | ||

| HIV-RNA < 50 copies/mL, n/N (%) | 0/27 (0%) | 129/145 (89.0%) |

| 12 Months | ||

| HIV-RNA < 50 copies/mL, n/N (%) | 21/26 (80.8%) | 117/128 (91.4%) |

| No Virological Suppression (HIV-RNA ≥ 50), n | 5 | 11 |

| No Virological Data, n | 1 | 18 |

| 24 Months | ||

| HIV-RNA < 50 copies/mL, n/N (%) | 18/21 (85.7%) | 92/98 (93.9%) |

| No Virological Suppression (HIV-RNA ≥ 50), n | 3 | 6 |

| No Virological Data, n | 6 | 48 |

| Parameter | Timepoint | Naïve Cohort (n = 27) | p-Value | Experienced Cohort (n = 146) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunological Response | |||||

| CD4+ Count (cells/μL), mean ± SD | Baseline | 176.4 ± 180.9 | - | 662.7 ± 389.5 | - |

| 12 Months | 402.6 ± 273.9 | <0.001 | 641.4 ± 351.2 | 0.391 | |

| 24 Months | 449.5 ± 270.7 | <0.001 | 680.4 ± 390.9 | 0.225 | |

| CD4+/CD8+ Ratio, mean ± SD | Baseline | 0.28 ± 0.28 | - | 0.95 ± 0.76 | - |

| 12 Months | 0.57 ± 0.43 | <0.001 | 1.02 ± 0.86 | <0.001 | |

| 24 Months | 0.73 ± 0.52 | <0.001 | 1.12 ± 1.02 | <0.001 |

| Parameter | Timepoint | Naïve Cohort (n = 27) | p-Value | Experienced Cohort (n = 146) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic Parameters | |||||

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL), mean ± SD | Baseline | 98.5 ± 28.7 | - | 96.6 ± 28.4 | - |

| 12 Months | 93.2 ± 11.9 | 0.983 | 109.1 ± 94.3 | 0.036 | |

| 24 Months | 90.4 ± 14.3 | 0.690 | 98.8 ± 26.5 | 0.061 | |

| TyG Index, mean ± SD | Baseline | 4.72 ± 0.30 | - | 4.69 ± 0.25 | - |

| 12 Months | 4.67 ± 0.37 | 0.352 | 4.67 ± 0.29 | 0.061 | |

| 24 Months | 4.67 ± 0.25 | 0.084 | 4.64 ± 0.25 | 0.005 | |

| Hepatic Parameters | |||||

| AST (U/L), mean ± SD | Baseline | 35.9 ± 30.1 | - | 22.4 ± 10.9 | - |

| 12 Months | 24.2 ± 10.7 | 0.020 | 23.0 ± 7.9 | 0.068 | |

| 24 Months | 23.6 ± 6.9 | 0.101 | 25.4 ± 11.5 | <0.001 | |

| ALT (U/L), mean ± SD | Baseline | 33.7 ± 35.3 | - | 23.3 ± 12.8 | - |

| 12 Months | 20.9 ± 12.2 | 0.028 | 25.1 ± 12.5 | 0.191 | |

| 24 Months | 22.9 ± 11.7 | 0.484 | 25.9 ± 14.6 | 0.248 | |

| Liver Fibrosis Index | |||||

| FIB-4 score, mean ± SD | Baseline | 2.90 ± 4.80 | - | 1.40 ± 0.67 | - |

| 12 Months | 1.57 ± 0.68 | 0.183 | 1.39 ± 0.60 | 0.153 | |

| 24 Months | 1.48 ± 0.90 | 0.024 | 1.51 ± 0.92 | 0.004 |

| Parameter | Baseline (n = 105) | 12 Months (n = 36) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver Stiffness (kPa), mean ± SD | 5.99 ± 2.99 | 6.88 ± 3.79 | 0.191 |

| CAP Score (dB/m), mean ± SD | 246.42 ± 66.45 | 249.24 ± 61.41 | 0.383 |

| Parameter | Overall (N = 41) | Naïve Cohort (n = 10) | Experienced Cohort (n = 31) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Discontinuations, n (% of cohort) | 41 (19.2%) | 10 (27.0%) | 31 (17.5%) |

| Reason for Discontinuation, n (% of column discontinuations) | |||

| Patient Choice | 13 (31.7%) | 3 (30.0%) | 10 (32.3%) |

| Toxicity | 9 (22.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 8 (25.8%) |

| Simplification | 7 (17.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (22.6%) |

| Failure | 2 (4.9%) | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (3.2%) |

| DDI (Drug–Drug Interaction) | 2 (4.9%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| CV Prevention | 5 (12.2%) | 1 (10.0%) | 4 (12.9%) |

| Death | 2 (4.9%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Median Time to Discontinuation, days | - | 352.5 | 437.0 |

| New Antiretroviral Regimen Prescribed, n | |||

| CAB-RPV (Long-Acting) | 13 | 3 | 10 |

| DTG/3TC | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| DTG + DOR | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| DOR + TAF/FTC | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| DRV/b + RAL | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| DOR/TDF/3TC | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| DTG + TAF/FTC | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| DRV/b + DTG | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| DRV/c/TAF/FTC | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| DTG + TDF/FTC | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| EFV/TDF/FTC | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| None (Interruption) | 2 | 2 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trizzino, M.; Pipitò, L.; Di Figlia, F.; Bonura, S.; Zimmerhofer, F.; Cicero, A.; Gioè, C.; Cascio, A. Effectiveness and Safety of Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide in People Living with HIV Aged 50 Years and Older: A Retrospective Analysis of Naïve and Treatment-Experienced Individuals. Viruses 2025, 17, 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111449

Trizzino M, Pipitò L, Di Figlia F, Bonura S, Zimmerhofer F, Cicero A, Gioè C, Cascio A. Effectiveness and Safety of Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide in People Living with HIV Aged 50 Years and Older: A Retrospective Analysis of Naïve and Treatment-Experienced Individuals. Viruses. 2025; 17(11):1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111449

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrizzino, Marcello, Luca Pipitò, Floriana Di Figlia, Silvia Bonura, Federica Zimmerhofer, Andrea Cicero, Claudia Gioè, and Antonio Cascio. 2025. "Effectiveness and Safety of Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide in People Living with HIV Aged 50 Years and Older: A Retrospective Analysis of Naïve and Treatment-Experienced Individuals" Viruses 17, no. 11: 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111449

APA StyleTrizzino, M., Pipitò, L., Di Figlia, F., Bonura, S., Zimmerhofer, F., Cicero, A., Gioè, C., & Cascio, A. (2025). Effectiveness and Safety of Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide in People Living with HIV Aged 50 Years and Older: A Retrospective Analysis of Naïve and Treatment-Experienced Individuals. Viruses, 17(11), 1449. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17111449