Molecular Epidemiology of Hepatitis E Virus in Hungary (2018–2025): Emergence of Rare Subtypes and First Detection of HEV-4 in Central Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Detection and Genotyping of Hepatitis E Virus RNA Based on ORF2

2.3. Illumina Whole-Genome Sequencing

2.4. Mutational and Phylogenetic Analyses

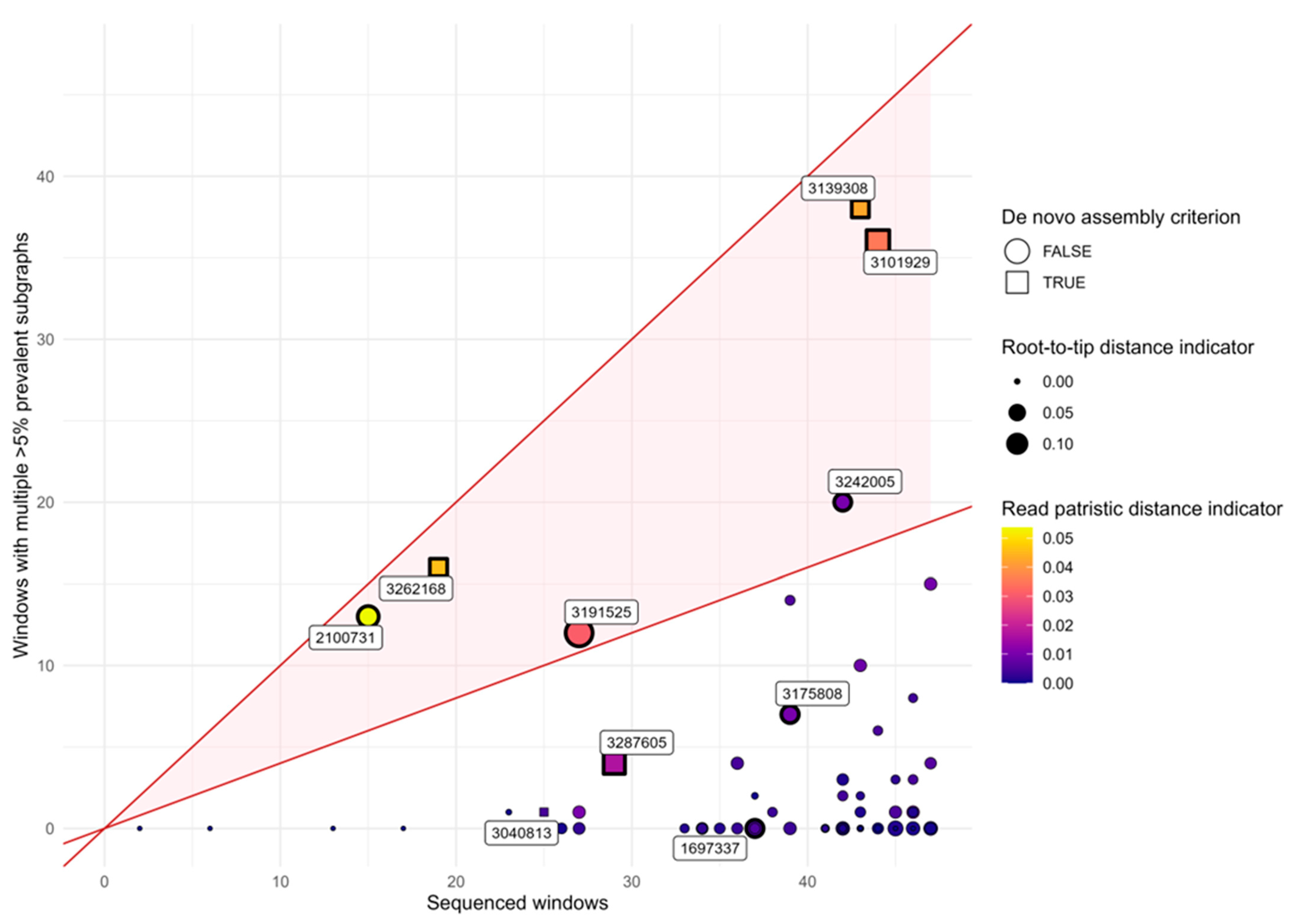

2.5. Detection of Multiple Infections Using Phyloscanner

- De novo assembly criterion: More than one overlapping but genetically distinct contig was assembled from the reads by either IVA or rnaviralSPAdes.

- Phyloscanner multiple subgraph criterion: In at least 40% of analyzed windows, multiple subgraphs with a prevalence of at least 5% were identified.

- Phyloscanner diversity criterion: The sample falls within the top two deciles among all samples in both of the following indicators:

- a.

- Root-to-tip distance indicator: The mean (across all windows) of the difference between (i) the mean patristic distance from all tips from this host to their most recent common ancestor (MRCA), and (ii) the mean patristic distance from the tips within the largest subgraph from the host to the MRCA of that subgraph.

- b.

- Read patristic distance indicator: The mean (across all windows) of the difference between (i) the mean pairwise patristic distance among all tips from the host, and (ii) the mean pairwise patristic distance among tips within the largest subgraph.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Accession Numbers

3. Results

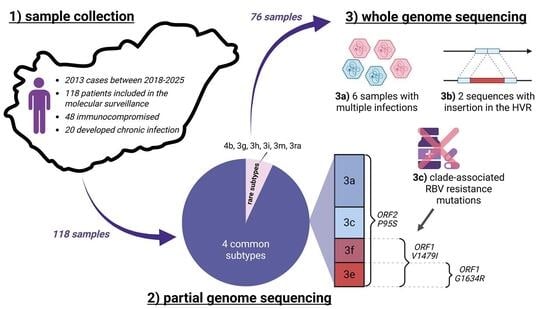

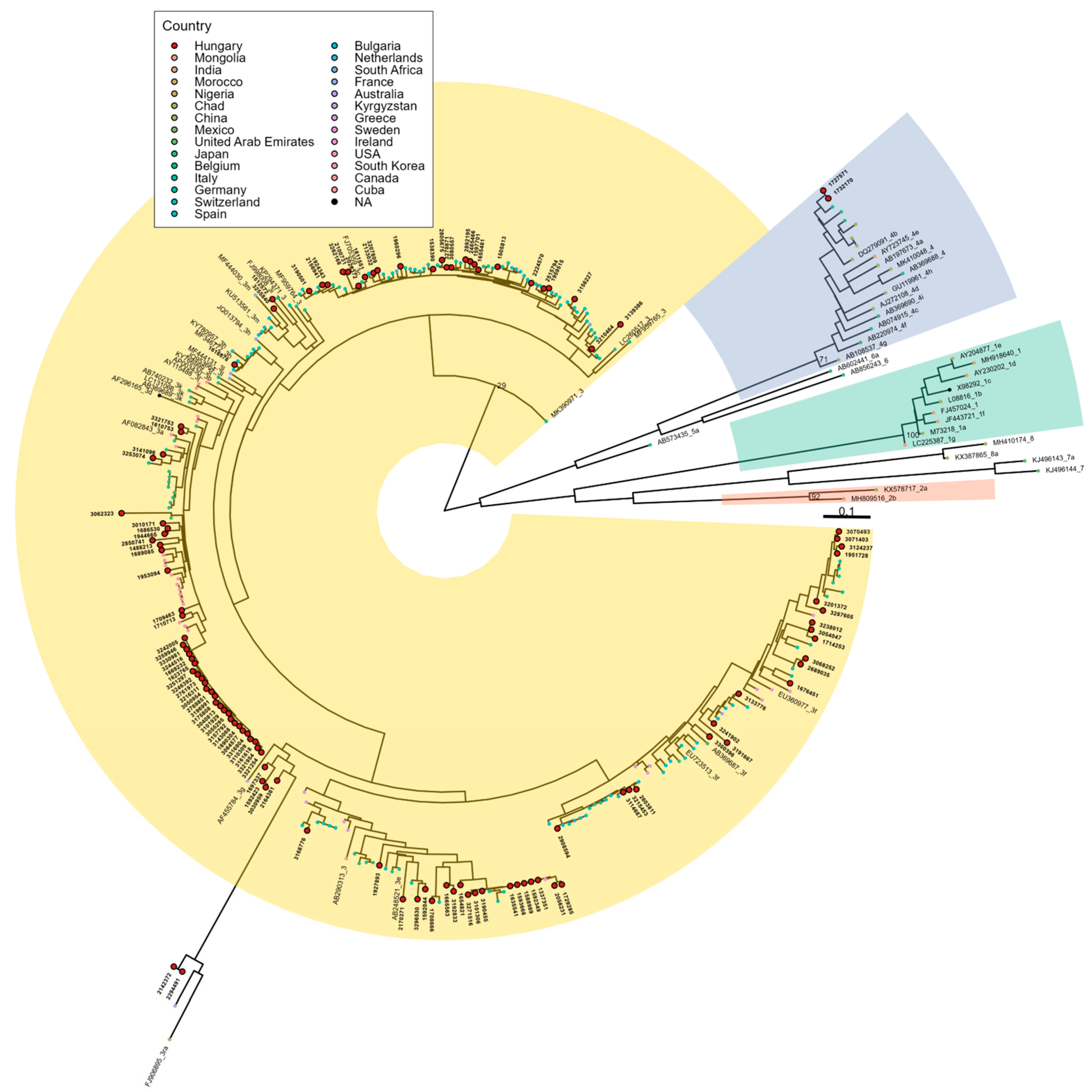

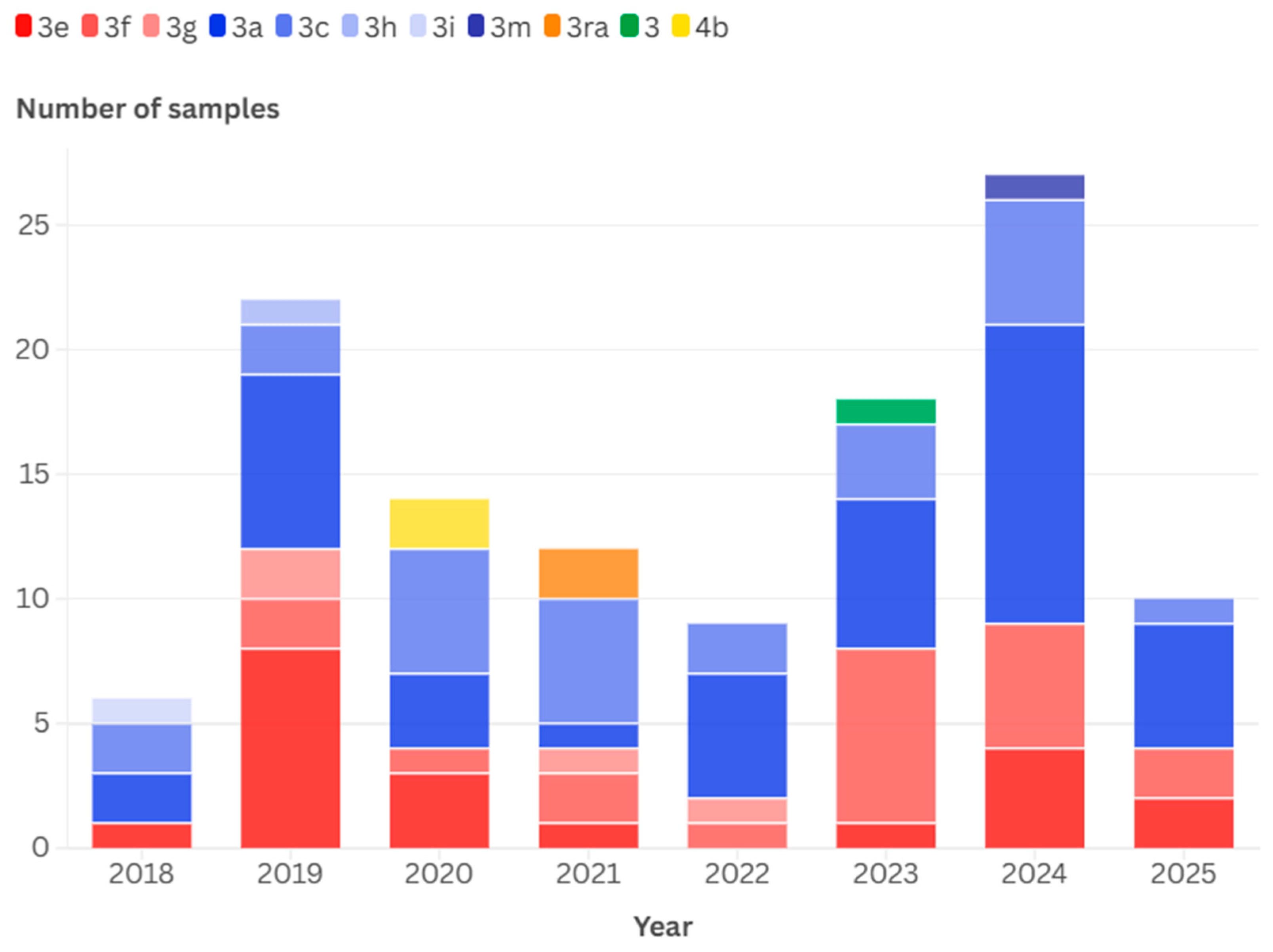

3.1. Detected Genotypes

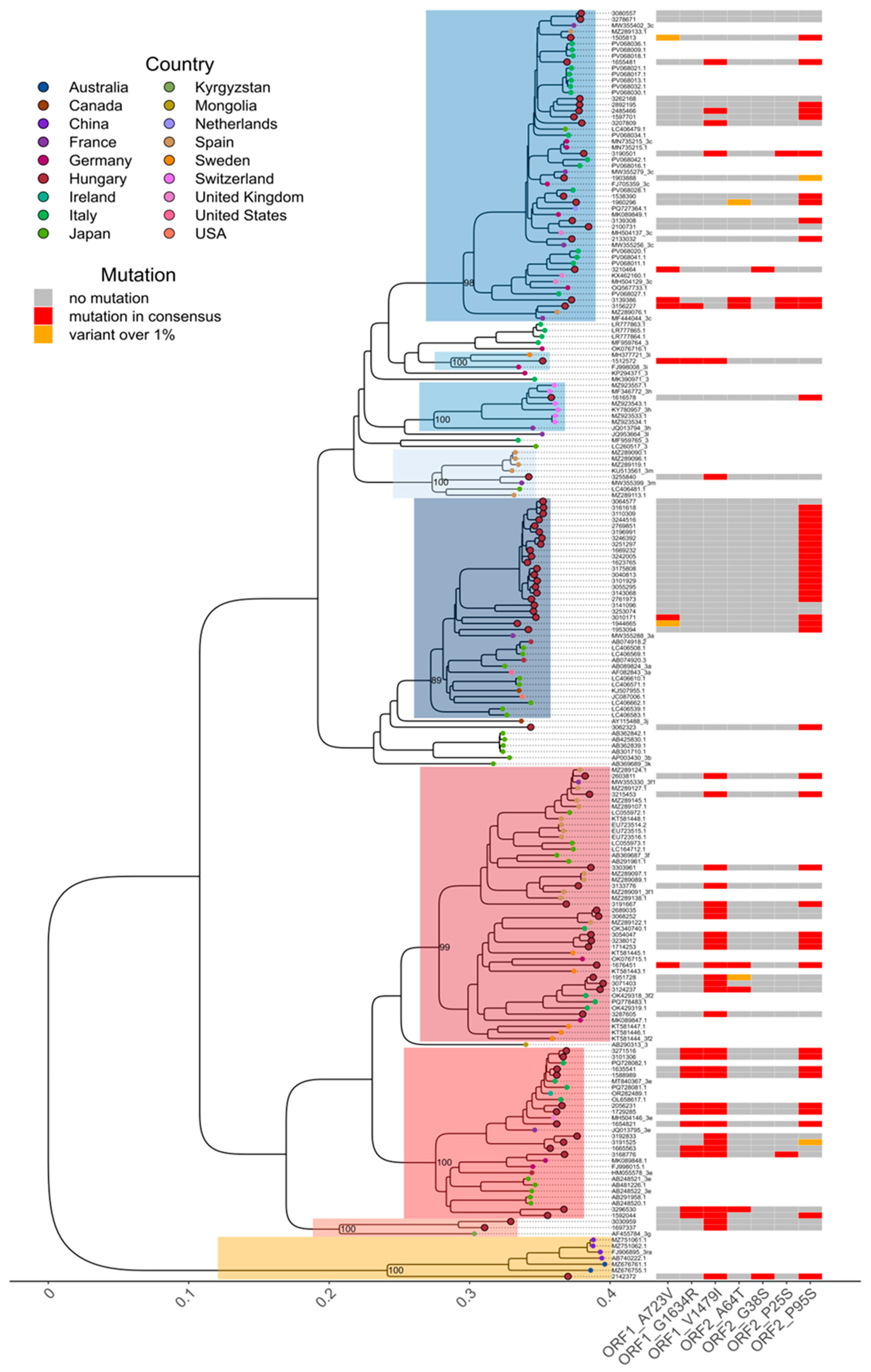

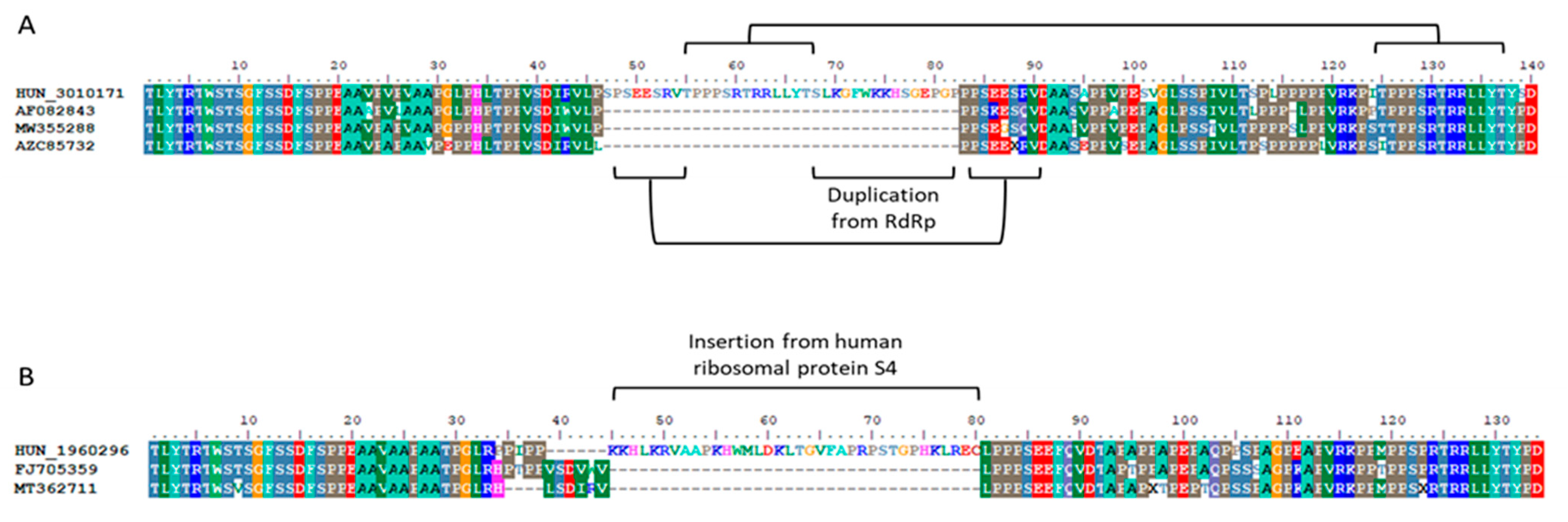

3.2. Detection of Ribavirin Resistance and Analysis of the Proline-Rich Region

3.3. In Silico Validation of Multiple Infections

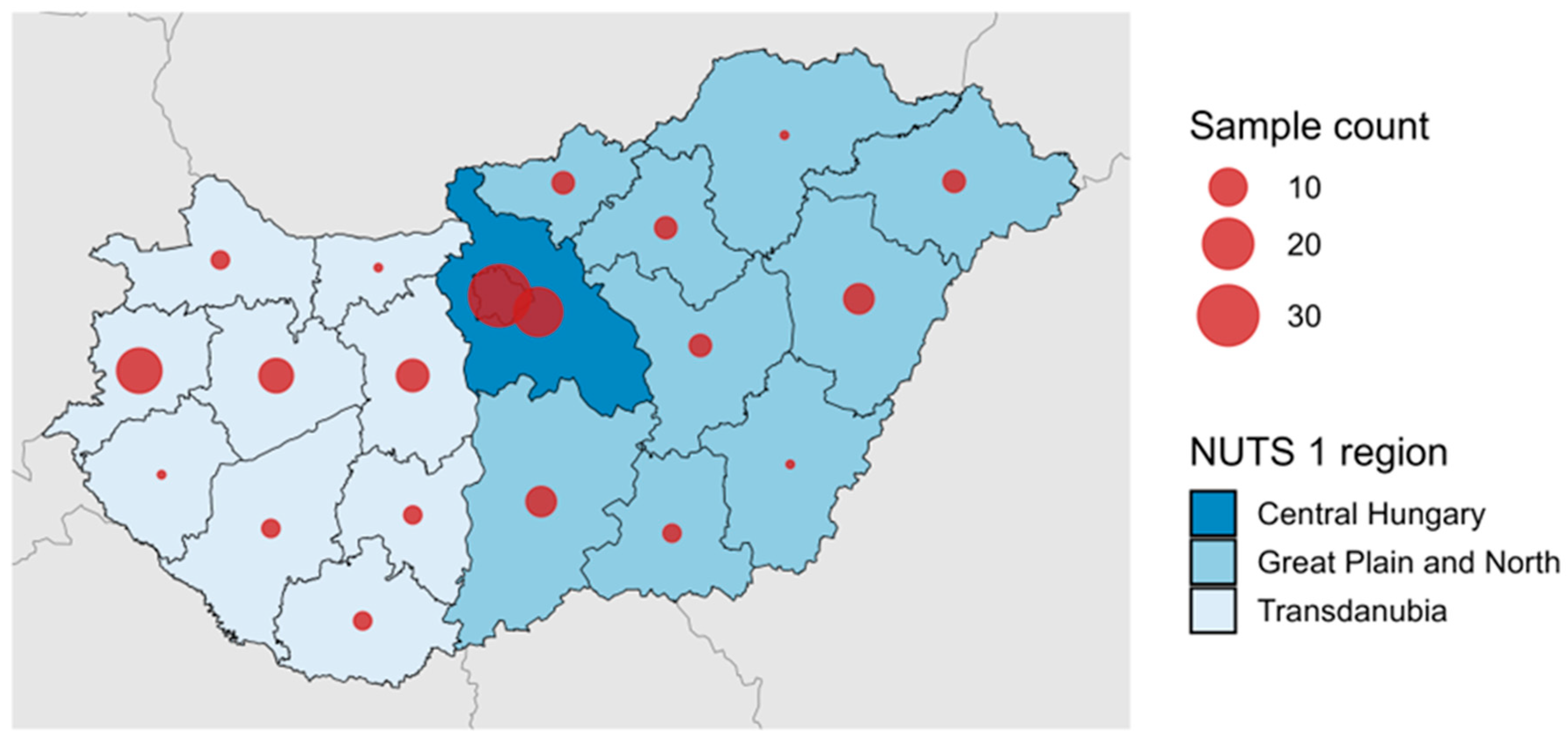

3.4. Temporal and Geographical Distribution of Detected HEV-3 Subtypes

3.5. Immunocompromised Patients and Chronic Infections

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HEV | Hepatitis E virus |

| HVR | Hypervariable Region |

| NUTS | Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics |

| ORF | Open reading frame |

| PPR | Polyproline region |

| SOT | Solid organ transplant |

| SVR | Sustained viral response |

| RdRp | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase |

| RIVM | Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Acute hepatitis E—Level 4 Cause [Factsheet]. Global Burden of Disease. 2021. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/diseases-injuries-risks/factsheets/2021-acute-hepatitis-e-level-4-disease (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Lhomme, S.; Marion, O.; Abravanel, F.; Izopet, J.; Kamar, N. Clinical Manifestations, Pathogenesis and Treatment of Hepatitis E Virus Infections. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, A.K.; Kumar, G.; Dayal, V.M.; Ranjan, A.; Suchismita, A. Neurological manifestations of hepatitis E virus infection: An overview. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 2090–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Gracia, M.T.; Suay-García, B.; Mateos-Lindemann, M.L. Hepatitis E and pregnancy: Current state. Rev. Med. Virol. 2017, 27, e1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Profio, F.; Sarchese, V.; Palombieri, A.; Fruci, P.; Lanave, G.; Robetto, S.; Martella, V.; Di Martino, B. Current Knowledge of Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) Epidemiology in Ruminants. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakze-van der Honing, R.W.; van Coillie, E.; Antonis, A.F.; van der Poel, W.H. First isolation of hepatitis E virus genotype 4 in Europe through swine surveillance in the Netherlands and Belgium. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e22673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monne, I.; Ceglie, L.; DIMartino, G.; Natale, A.; Zamprogna, S.; Morreale, A.; Rampazzo, E.; Cattoli, G.; Bonfanti, L. Hepatitis E virus genotype 4 in a pig farm, Italy, 2013. Epidemiol. Infect. 2015, 143, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colson, P.; Romanet, P.; Moal, V.; Borentain, P.; Purgus, R.; Benezech, A.; Motte, A.; Gérolami, R. Autochthonous infections with hepatitis E virus genotype 4, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2012, 18, 1361–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbuglia, A.R.; Scognamiglio, P.; Petrosillo, N.; Mastroianni, C.M.; Sordillo, P.; Gentile, D.; La Scala, P.; Girardi, E.; Capobianchi, M.R. Hepatitis E virus genotype 4 outbreak, Italy, 2011. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, N.; Izopet, J.; Pavio, N.; Aggarwal, R.; Labrique, A.; Wedemeyer, H.; Dalton, H.R. Hepatitis E virus infection. Nature reviews. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, N.; Abravanel, F.; Selves, J.; Garrouste, C.; Esposito, L.; Lavayssire, L.; Cointault, O.; Ribes, D.; Cardeau, I.; Nogier, M.B.; et al. Influence of immunosuppressive therapy on the natural history of genotype 3 hepatitis-E virus infection after organ transplantation. Transplantation 2010, 89, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamar, N.; Abravanel, F.; Behrendt, P.; Hofmann, J.; Pageaux, G.P.; Barbet, C.; Moal, V.; Couzi, L.; Horvatits, T.; De Man, R.A.; et al. Ribavirin for Hepatitis E Virus Infection After Organ Transplantation: A Large European Retrospective Multicenter Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Terada, S.; Kokuryu, H.; Arai, M.; Mishiro, S. A wild boar-derived hepatitis E virus isolate presumably representing so far unidentified “genotype 5”. Kanzo 2010, 51, 536–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Nishizawa, T.; Sato, H.; Sato, Y.; Jirintai; Nagashima, S.; Okamoto, H. Analysis of the full-length genome of a hepatitis E virus isolate obtained from a wild boar in Japan that is classifiable into a novel genotype. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.H.; Tan, B.H.; Teo, E.C.Y.; Lim, S.G.; Dan, Y.Y.; Wee, A.; Aw, P.P.K.; Zhu, Y.; Hibberd, M.L.; Tan, C.K.; et al. Chronic infection with camelid hepatitis E virus in a liver transplant recipient who regularly consumes camel meat and milk. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 355–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Teng, J.L.L.; Cao, K.Y.; Wernery, U.; Schountz, T.; Chiu, T.H.; Tsang, A.K.L.; Wong, P.C.; Wong, E.Y.M.; et al. New hepatitis E virus genotype in Bactrian camels, Xinjiang, China, 2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 2219–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Yip, C.C.Y.; Wu, S.; Cai, J.; Zhang, A.J.; Leung, K.H.; Chung, T.W.H.; Chan, J.F.W.; Chan, W.-M.; Teng, J.L.L.; et al. Rat hepatitis E virus as cause of persistent hepatitis after liver transplant. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 2241–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andonov, A.; Robbins, M.; Borlang, J.; Cao, J.; Hatchette, T.; Stueck, A.; Deschambault, Y.; Murnaghan, K.; Varga, J.; Johnston, L. Rat Hepatitis E Virus Linked to Severe Acute Hepatitis in an Immunocompetent Patient. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, 951–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.B.; Simmonds, P.; Izopet, J.; Oliveira-Filho, E.F.; Ulrich, R.G.; Johne, R.; Koenig, M.; Jameel, S.; Harrison, T.J.; Meng, X.J.; et al. Proposed reference sequences for hepatitis E virus subtypes. J. Gen. Virol. 2016, 97, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.B.; Izopet, J.; Nicot, F.; Simmonds, P.; Jameel, S.; Meng, X.J.; Norder, H.; Okamoto, H.; van der Poel, W.H.M.; Reuter, G.; et al. Update: Proposed reference sequences for subtypes of hepatitis E virus (species Orthohepevirus A). J. Gen. Virol. 2020, 101, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moal, V.; Gerolami, R.; Colson, P. First human case of co-infection with two different subtypes of hepatitis E virus. Intervirology 2012, 55, 484–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Takagi, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Maruhashi, K.; Kosone, T.; Kakizaki, S.; Sato, K.; Yamada, M.; Nagashima, S.; Takahashi, M.; et al. Autochthonous sporadic acute hepatitis E caused by two distinct subgenotype 3b hepatitis E virus strains with only 90% nucleotide identity. Clin. J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 10, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymant, C.; Hall, M.; Ratmann, O.; Bonsall, D.; Golubchik, T.; De Cesare, M.; Gall, A.; Cornelissen, M.; Fraser, C.; STOP-HCV Consortium; et al. PHYLOSCANNER: Inferring Transmission from Within- and Between-Host Pathogen Genetic Diversity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.A.; Brizzi, A.; Xi, X.; Galiwango, R.M.; Moyo, S.; Ssemwanga, D.; Blenkinsop, A.; Redd, A.D.; Abeler-Dörner, L.; Fraser, C.; et al. Quantifying prevalence and risk factors of HIV multiple infection in Uganda from population-based deep-sequence data. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1013065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdy, M.A.; Lara, J.; Khudyakov, Y.E. The Hepatitis E Virus Polyproline Region Is Involved in Viral Adaptation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pudupakam, R.S.; Huang, Y.W.; Opriessnig, T.; Halbur, P.G.; Pierson, F.W.; Meng, X.J. Deletions of the hypervariable region (HVR) in open reading frame 1 of hepatitis E virus do not abolish virus infectivity: Evidence for attenuation of HVR deletion mutants in vivo. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Torian, U.; Faulk, K.; Mather, K.; Engle, R.E.; Thompson, E.; Bonkovsky, H.L.; Emerson, S.U. A naturally occurring human/hepatitis E recombinant virus predominates in serum but not in faeces of a chronic hepatitis E patient and has a growth advantage in cell culture. J. Gen. Virol. 2012, 93, 526–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Chimeno, M.; Cenalmor, A.; Garcia-Lugo, M.A.; Hernandez, M.; Rodriguez-Lazaro, D.; Avellon, A. Proline-Rich Hypervariable Region of Hepatitis E Virus: Arranging the Disorder. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todt, D.; Gisa, A.; Radonic, A.; Nitsche, A.; Behrendt, P.; Suneetha, P.V.; Pischke, S.; Bremer, B.; Brown, R.J.; Manns, M.P.; et al. In vivo evidence for ribavirin-induced mutagenesis of the hepatitis E virus genome. Gut 2016, 65, 1733–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debing, Y.; Gisa, A.; Dallmeier, K.; Pischke, S.; Bremer, B.; Manns, M.; Wedemeyer, H.; Suneetha, P.V.; Neyts, J. A mutation in the hepatitis E virus RNA polymerase promotes its replication and associates with ribavirin treatment failure in organ transplant recipients. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 1008–1011.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debing, Y.; Ramière, C.; Dallmeier, K.; Piorkowski, G.; Trabaud, M.A.; Lebossé, F.; Scholtès, C.; Roche, M.; Legras-Lachuer, C.; de Lamballerie, X.; et al. Hepatitis E virus mutations associated with ribavirin treatment failure result in altered viral fitness and ribavirin sensitivity. J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hriskova, K.; Marosevic, D.; Belting, A.; Wenzel, J.J.; Carl, A.; Katz, K. Epidemiology of Hepatitis E in 2017 in Bavaria, Germany. Food Environ. Virol. 2021, 13, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oeser, C.; Vaughan, A.; Said, B.; Ijaz, S.; Tedder, R.; Haywood, B.; Warburton, F.; Charlett, A.; Elson, R.; Morgan, D. Epidemiology of Hepatitis E in England and Wales: A 10-Year Retrospective Surveillance Study, 2008–2017. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 220, 802–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbuglia, A.R.; Bruni, R.; Villano, U.; Vairo, F.; Lapa, D.; Madonna, E.; Picchi, G.; Binda, B.; Mariani, R.; De Paulis, F.; et al. Hepatitis E Outbreak in the Central Part of Italy Sustained by Multiple HEV Genotype 3 Strains, June-December 2019. Viruses 2021, 13, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemeršić, L.; Prpić, J.; Brnić, D.; Keros, T.; Pandak, N.; Đaković Rode, O. Genetic diversity of hepatitis E virus (HEV) strains derived from humans, swine and wild boars in Croatia from 2010 to 2017. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand-Abravanel, F.; Mansuy, J.M.; Dubois, M.; Kamar, N.; Peron, J.M.; Rostaing, L.; Izopet, J. Hepatitis E virus genotype 3 diversity, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogema, B.M.; Hakze-van der Honing, R.W.; Molier, M.; Zaaijer, H.L.; van der Poel, W.H.M. Comparison of Hepatitis E Virus Sequences from Humans and Swine, The Netherlands, 1998–2015. Viruses 2021, 13, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, S.; Said, B.; Boxall, E.; Smit, E.; Morgan, D.; Tedder, R.S. Indigenous hepatitis E in England and wales from 2003 to 2012: Evidence of an emerging novel phylotype of viruses. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, 1212–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Lopez, P.; Frias, M.; Perez-Jimenez, A.B.; Freyre-Carrillo, C.; Pineda, J.A.; Fuentes, A.; Alados, J.C.; Ramirez-Arellano, E.; Viciana, I.; Corona-Mata, D.; et al. Temporal changes in the genotypes of Paslahepevirus balayani in southern Spain and their possible link with changes in pig trade imports. One Health 2023, 16, 100539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonlanthen-Specker, I.; Stephan, R.; Sidler, X.; Moor, D.; Fraefel, C.; Bachofen, C. Genetic Diversity of Hepatitis E Virus Type 3 in Switzerland-From Stable to Table. Animals 2021, 11, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Chimeno, M.; Bartúren, S.; García-Lugo, M.A.; Morago, L.; Rodríguez, Á.; Galán, J.C.; Pérez-Rivilla, A.; Rodríguez, M.; Millán, R.; Del Álamo, M.; et al. Hepatitis E virus genotype 3 microbiological surveillance by the Spanish Reference Laboratory: Geographic distribution and phylogenetic analysis of subtypes from 2009 to 2019. Eurosurveillance 2022, 27, 2100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, G.; Fodor, D.; Forgách, P.; Kátai, A.; Szucs, G. Characterization and zoonotic potential of endemic hepatitis E virus (HEV) strains in humans and animals in Hungary. J. Clin. Virol. 2009, 44, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgách, P.; Nowotny, N.; Erdélyi, K.; Boncz, A.; Zentai, J.; Szucs, G.; Reuter, G.; Bakonyi, T. Detection of hepatitis E virus in samples of animal origin collected in Hungary. Vet. Microbiol. 2010, 143, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankovics, P.; Némethy, O.; Boros, Á.; Pár, G.; Szakály, P.; Reuter, G. Four-year long (2014–2017) clinical and laboratory surveillance of hepatitis E virus infections using combined antibody, molecular, antigen and avidity detection methods: Increasing incidence and chronic HEV case in Hungary. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 124, 104284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.F.; Haqshenas, G.; Guenette, D.K.; Halbur, P.G.; Schommer, S.K.; Pierson, F.W.; Toth, T.E.; Meng, X.J. Detection by reverse transcription-PCR and genetic characterization of field isolates of swine hepatitis E virus from pigs in different geographic regions of the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulder, A.C.; Kroneman, A.; Franz, E.; Vennema, H.; Tulen, A.D.; Takkinen, J.; Hofhuis, A.; Adlhoch, C.; Members of HEVnet. HEVnet: A One Health, collaborative, interdisciplinary network and sequence data repository for enhanced hepatitis E virus molecular typing, characterisation and epidemiological investigations. Eurosurveillance 2019, 24, 1800407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Harms, D.; Papp, C.P.; Niendorf, S.; Jacobsen, S.; Lütgehetmann, M.; Pischke, S.; Wedermeyer, H.; Hofmann, J.; Bock, C.T. Comprehensive Molecular Approach for Characterization of Hepatitis E Virus Genotype 3 Variants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2018, 56, e01686-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dencs, Á.; Hettmann, A.; Barcsay, E.; Rusvai, E.; Kozma, E.; Takács, M. Hepatitis A virus subtype IB outbreak among MSM in Hungary with a link to a frozen berry source. Infect. Genet. Evol. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evol. Genet. Infect. Dis. 2024, 123, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsichla, L.; Zeeb, M.; Fazekas, D.; Áy, É.; Müller, D.; Metzner, K.J.; Kouyos, R.D.; Müller, V. Comparative Evalua-tion of Open-Source Bioinformatics Pipelines for Full-Length Viral Genome Assembly. Viruses 2024, 16, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilm, A.; Aw, P.P.K.; Bertrand, D.; Yeo, G.H.T.; Ong, S.H.; Wong, C.H.; Khor, C.C.; Petric, R.; Hibberd, M.L.; Nagarajan, N. LoFreq: A sequence-quality aware, ultra-sensitive variant caller for uncovering cell-population heterogeneity from high-throughput sequencing datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 11189–11201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, M.; Gall, A.; Ong, S.H.; Brener, J.; Ferns, B.; Goulder, P.; Nastouli, E.; Keane, J.A.; Kellam, P.; Otto, T.D. IVA: Accurate de novo assembly of RNA virus genomes. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2374–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushmanova, E.; Antipov, D.; Lapidus, A.; Prjibelski, A.D. rnaSPAdes: A de novo transcriptome assembler and its application to RNA-Seq data. GigaScience 2019, 8, giz100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, V.; Afgan, E.; Gu, Q.; Clements, D.; Blankenberg, D.; Goecks, J.; Taylor, J.; Nekrutenko, A. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2020 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W395–W402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlov, A.M.; Darriba, D.; Flouri, T.; Morel, B.; Stamatakis, A. RAxML-NG: A fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 4453–4455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, T.A. BIOEDIT: A user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/ NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lhomme, S.; Nicot, F.; Jeanne, N.; Dimeglio, C.; Roulet, A.; Lefebvre, C.; Carcenac, R.; Manno, M.; Dubois, M.; Peron, J.M.; et al. Insertions and Duplications in the Polyproline Region of the Hepatitis E Virus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Center for Public Health and Pharmacy. Division of Epidemiology and Infection Control. Annual epidemiological reports, in Hungarian. Available online: https://nnk.gov.hu/index.php/jarvanyugy/foosztaly-kezdolapja.html (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Veneri, C.; Brandtner, D.; Mancini, P.; Bonanno Ferraro, G.; Iaconelli, M.; Del Giudice, C.; Ciccaglione, A.R.; Bruni, R.; Equestre, M.; Marcantonio, C.; et al. Detection and full genomic sequencing of rare hepatitis E virus genotype 4d in Italian wastewater, undetected by clinical surveillance. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 913, 169698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Wagner, A.L.; Song, Y.; Chen, X.; Lu, Y. Distribution and phylogenetics of hepatitis E virus genotype 4 in humans and animals. Zoonoses Public Health 2022, 69, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungarian Central Statistical Office: Pork Meat Trade Balance. Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/mez/hu/mez0048.html (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Institute of Agricultural Economics. Agricultural Market Reports, in Hungarian. Available online: https://www.aki.gov.hu/product-category/agrarpiaci-jelentesek/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Suin, V.; Klamer, S.E.; Hutse, V.; Wautier, M.; Jacques, M.; Abady, M.; Lamoral, S.; Verburgh, V.; Thomas, I.; Brochier, B.; et al. Epidemiology and genotype 3 subtype dynamics of hepatitis E virus in Belgium, 2010 to 2017. Eurosurveillance 2019, 24, 1800141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemmerer, M.; Wenzel, J.J.; Stark, K.; Faber, M. Molecular epidemiology and genotype-specific disease severity of hepatitis E virus infections in Germany, 2010–2019. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 1754–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, I.; Nemes, I.; Bognár, L.; Terjék, Z.; Molnár, T.; Abonyi, T.; Bálint, Á.; Horváth, D.G.; Balka, G. Eradication of PRRS from Hungarian Pig Herds between 2014 and 2022. Animals 2023, 13, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasickova, P.; Slany, M.; Chalupa, P.; Holub, M.; Svoboda, R.; Pavlik, I. Detection and phylogenetic characterization of human hepatitis E virus strains, Czech Republic. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 917–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackova, A.; Dudasova, K.; Salamunova, S.; Mandelik, R.; Novotny, J.; Vilcek, S. Identification and genetic diversity of hepatitis E virus in domestic swine from Slovakia. BMC Vet. Res. 2021, 17, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priemer, G.; Cierniak, F.; Wolf, C.; Ulrich, R.G.; Groschup, M.H.; Eiden, M. Co-Circulation of Different Hepatitis E Virus Genotype 3 Subtypes in Pigs and Wild Boar in North-East Germany, 2019. Pathogens 2022, 11, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salines, M.; Barnaud, E.; Andraud, M.; Eono, F.; Renson, P.; Bourry, O.; Pavio, N.; Rose, N. Hepatitis E virus chronic infection of swine co-infected with Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome Virus. Vet. Res. 2015, 46, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudášová, K.; Pavlová, A.; Kočíková, B.; Urda Dolinská, M.; Šalamúnová, S.; Molnár, L.; Kottferová, L.; Jacková, A. Molecular Detection and Genetic Typing of Hepatitis E Virus in Wild Animals from Slovakia. Food Environ. Virol. 2025, 17, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, M.; Schenk, J.; De Somer, T.; Roskams, T.; Locus, T.; Klamer, S.; Subissi, L.; Suin, V.; Delwaide, J.; Stärkel, P.; et al. Viral clade is associated with severity of symptomatic genotype 3 hepatitis Evirus infections in Belgium 2010–2018. J. Hepatol. 2023, 78, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, M.; Sloan, W.T.; Quince, C. Benchmarking of viral haplotype reconstruction programmes: An overview of the capacities and limitations of currently available programmes. Brief. Bioinform. 2014, 15, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer Name | Sequence | Position on Reference Genome * | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15f | 5′-TGTGGTCGAYGCCATGGAG-3′ | 13–31 | Amplicon 1 |

| 2190r | 5′-TCGCTAGARAARCCAGATGTAGACC-3′ | 2139–2163 | |

| 24f | 5′-GYTGYTCRCGGCTYATGAC-3′ | 1032–1050 | Amplicon 2 |

| 41r | 5′-GCCATRTTCCAGACRGTRTTCCA-3′ | 4628–4650 | |

| 123f | 5′-AGGGTTGAGCAGAACCC(I)AAGAG-3′ | 2630–2652 | Amplicon 3 |

| 20r | 5′-GCRAAGGGGTTGGTTGGATG-3′ | 5340–5359 | |

| 126f | 5′-TGCCTATGCTGCCCGCGCCACC-3′ | 5212–5233 | Amplicon 4 |

| 22r | 5′-CCGGGTYTTRCCTACCTTC-3′ | 7127–7145 | |

| 137f | 5′-TCTAATGGCYTRGAYTGYACYGC-3′ | 1892–1914 | Sanger sequencing of PPR |

| 124r | 5′-ACCGAYGARGCCCGCTGCAT-3′ | 3182–3201 |

| Patient No | Sample Number | Age | Gender | Transplanted Organ /Condition | HEV Subtype | Duration of HEV RNA Positivity | Outcome | A723V | G1634R | V1479I | A64T | G38S | P25S | P95S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1610753 | 55.9 | f | liver | 3a | 6 months | cleared | n/a | ||||||

| 2 | 1623765 | 62.5 | m | heart | 3a | 8 months | cleared | |||||||

| 3 | 1635541 | 64.0 | f | liver | 3e | 3 months | cleared | |||||||

| 4 | 1665563 | 64.1 | f | kidney | 3e | 3 months | cleared | n/a | ||||||

| 5 | 1669232 | 57.2 | m | heart | 3a | 3 months | cleared | |||||||

| 6 | 1676451 | 63.2 | m | heart | 3f2 | 3 months | cleared | |||||||

| 7 | 1686530 | 69.6 | m | liver | 3a | 6 months | cleared | n/a | ||||||

| 8 | 1903888 | 71.2 | m | cirrhosis | 3c | 4 months | cleared | |||||||

| 9 | 1944665 | 26.9 | f | liver | 3a | 10 months | cleared | |||||||

| 10 | 2026372 | 40.0 | f | acute myeloid leukemia | 3c | 5 months | cleared | n/a | ||||||

| 11 | 2056231 | 26.6 | m | acute lymphoid leukemia | 3e | 3 months | cleared | |||||||

| 12 | 1538390 | 47.4 | f | liver | 3c | 38 months | cleared | |||||||

| 13 | 3010171 | 30.8 | f | liver | 3a | 52 months | cleared | |||||||

| 14 | 3101306 | 53.2 | f | kidney | 3e | 5 months | cleared | |||||||

| 15 | 3141096 | 45.2 | f | kidney | 3a | 17 months | ongoing | |||||||

| 16 | 3139308 | 62.8 | f | heart | 3c | 17 months | ongoing | |||||||

| 17 | 1960296 | 37.1 | f | heart | 3c | 12 months | cleared | |||||||

| 18 | 3238012 | 42.6 | f | heart | 3f2 | 10 months | ongoing | |||||||

| 19 | 3255840 | 33.9 | m | heart | 3m | 7 months | cleared | |||||||

| 20 | 3278671 | 48.6 | m | kidney | 3c | 5 months | ongoing | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dencs, Á.; Hettmann, A.; Zsichla, L.; Müller, V.; Dömötör, A.; Barna-Lázár, Á.; Barcsay, E.; Takács, M. Molecular Epidemiology of Hepatitis E Virus in Hungary (2018–2025): Emergence of Rare Subtypes and First Detection of HEV-4 in Central Europe. Viruses 2025, 17, 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17101389

Dencs Á, Hettmann A, Zsichla L, Müller V, Dömötör A, Barna-Lázár Á, Barcsay E, Takács M. Molecular Epidemiology of Hepatitis E Virus in Hungary (2018–2025): Emergence of Rare Subtypes and First Detection of HEV-4 in Central Europe. Viruses. 2025; 17(10):1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17101389

Chicago/Turabian StyleDencs, Ágnes, Andrea Hettmann, Levente Zsichla, Viktor Müller, Anett Dömötör, Ágnes Barna-Lázár, Erzsébet Barcsay, and Mária Takács. 2025. "Molecular Epidemiology of Hepatitis E Virus in Hungary (2018–2025): Emergence of Rare Subtypes and First Detection of HEV-4 in Central Europe" Viruses 17, no. 10: 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17101389

APA StyleDencs, Á., Hettmann, A., Zsichla, L., Müller, V., Dömötör, A., Barna-Lázár, Á., Barcsay, E., & Takács, M. (2025). Molecular Epidemiology of Hepatitis E Virus in Hungary (2018–2025): Emergence of Rare Subtypes and First Detection of HEV-4 in Central Europe. Viruses, 17(10), 1389. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17101389