Lytic Spectra of Tailed Bacteriophages: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

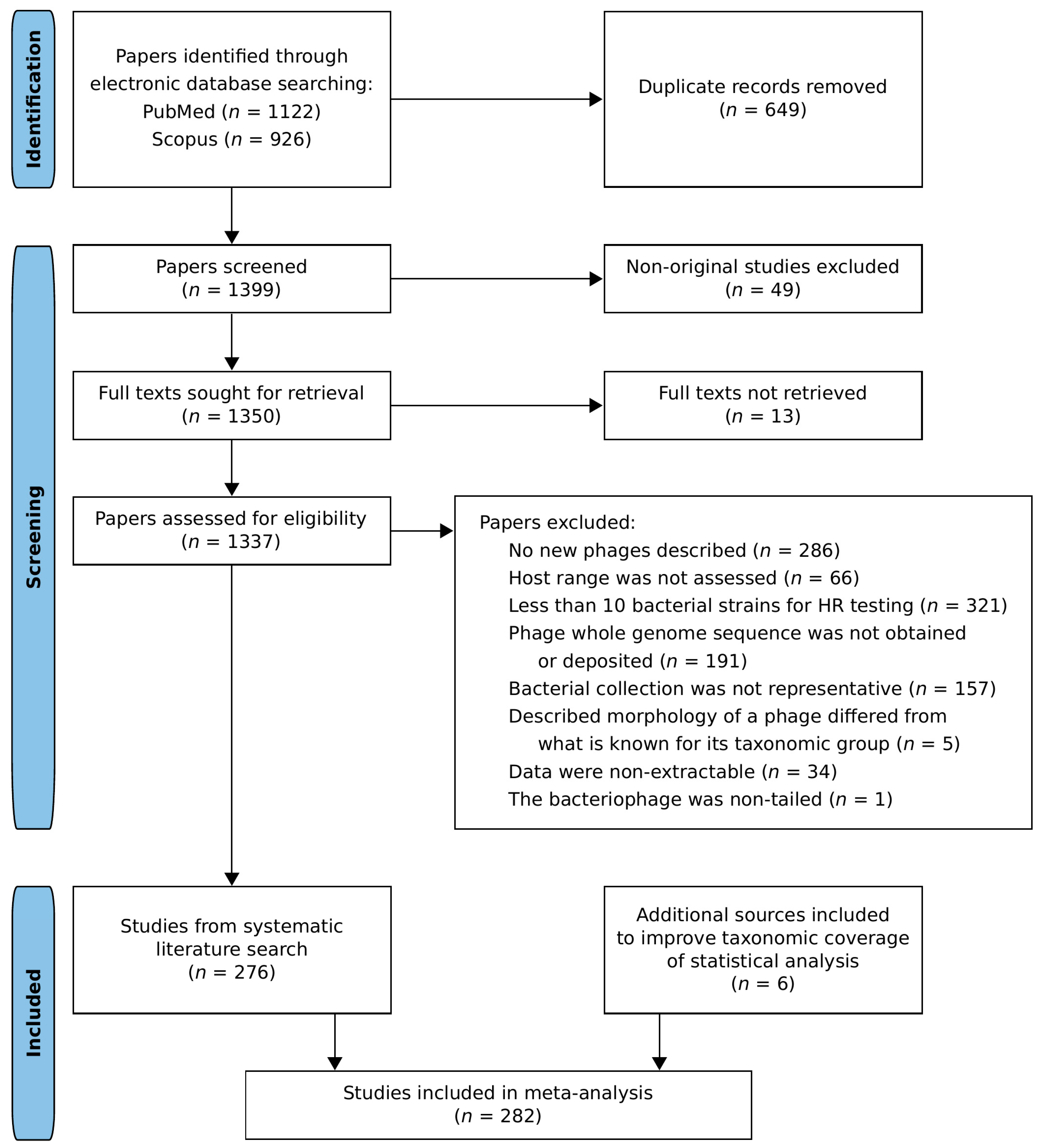

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

2.2. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Collection and Interpretation

2.4. Taxonomic Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

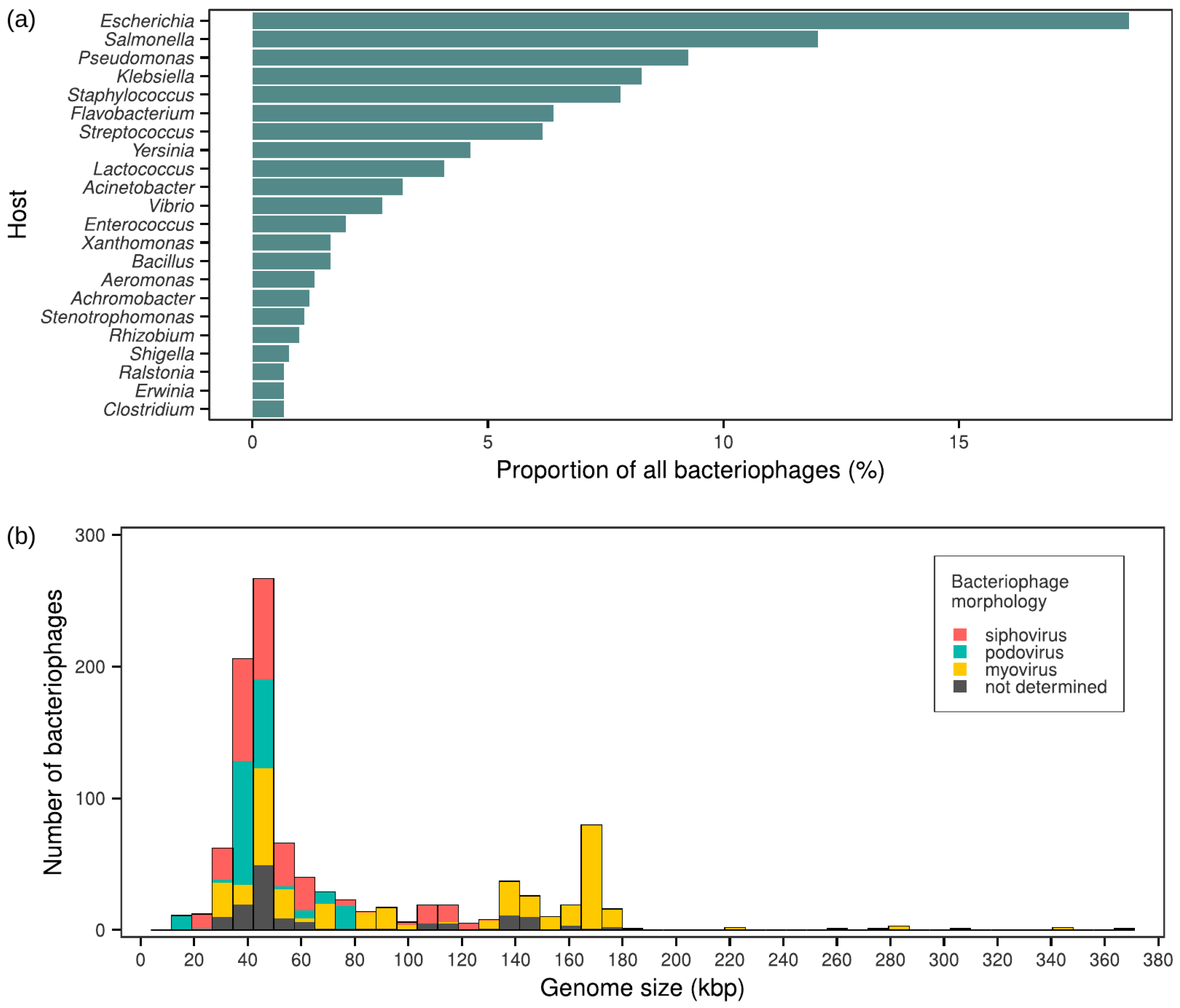

3.1. Dataset

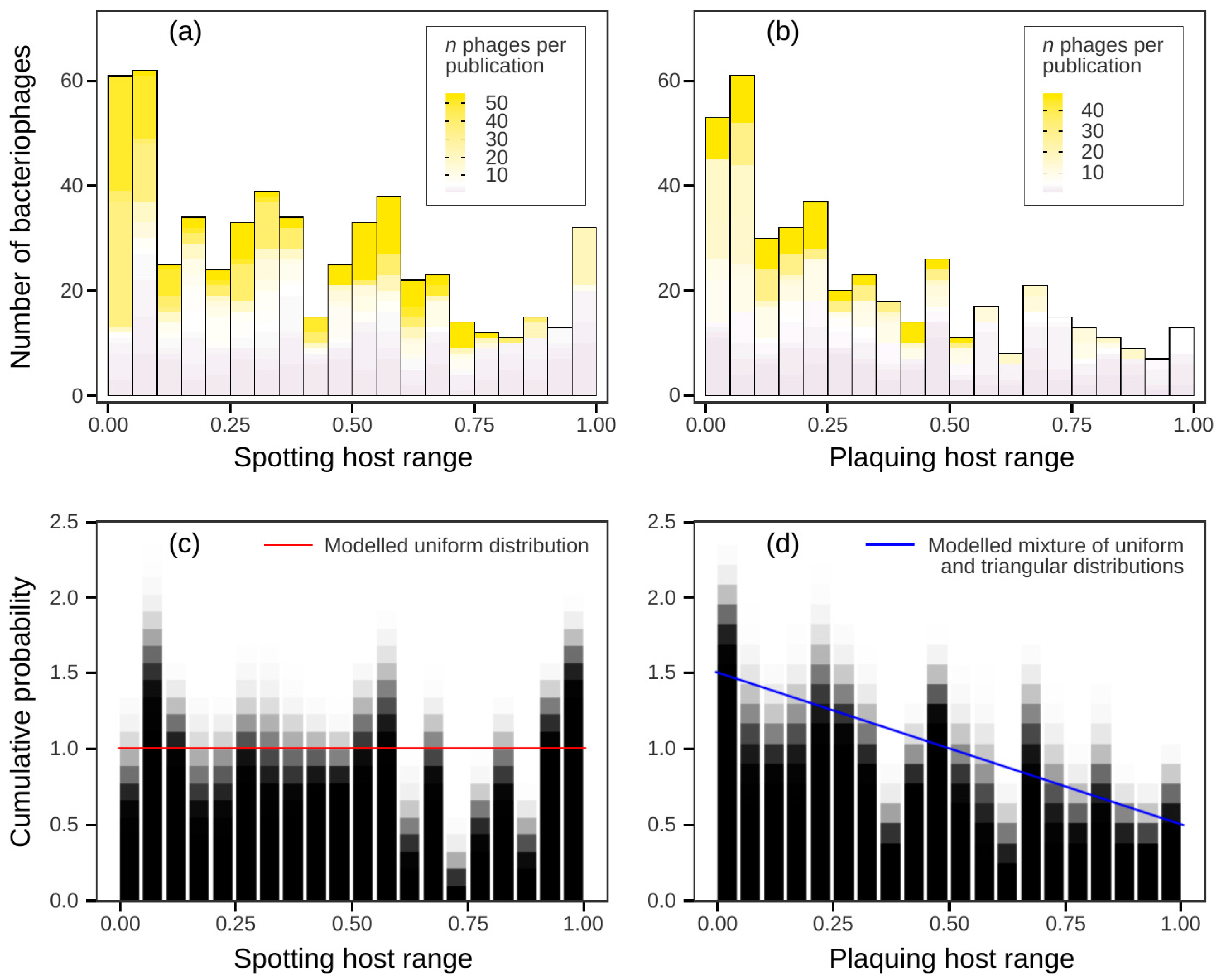

3.2. No Clear Boundaries Between Narrow and Broad Host Ranges

3.3. Family-Level Groups of Phages

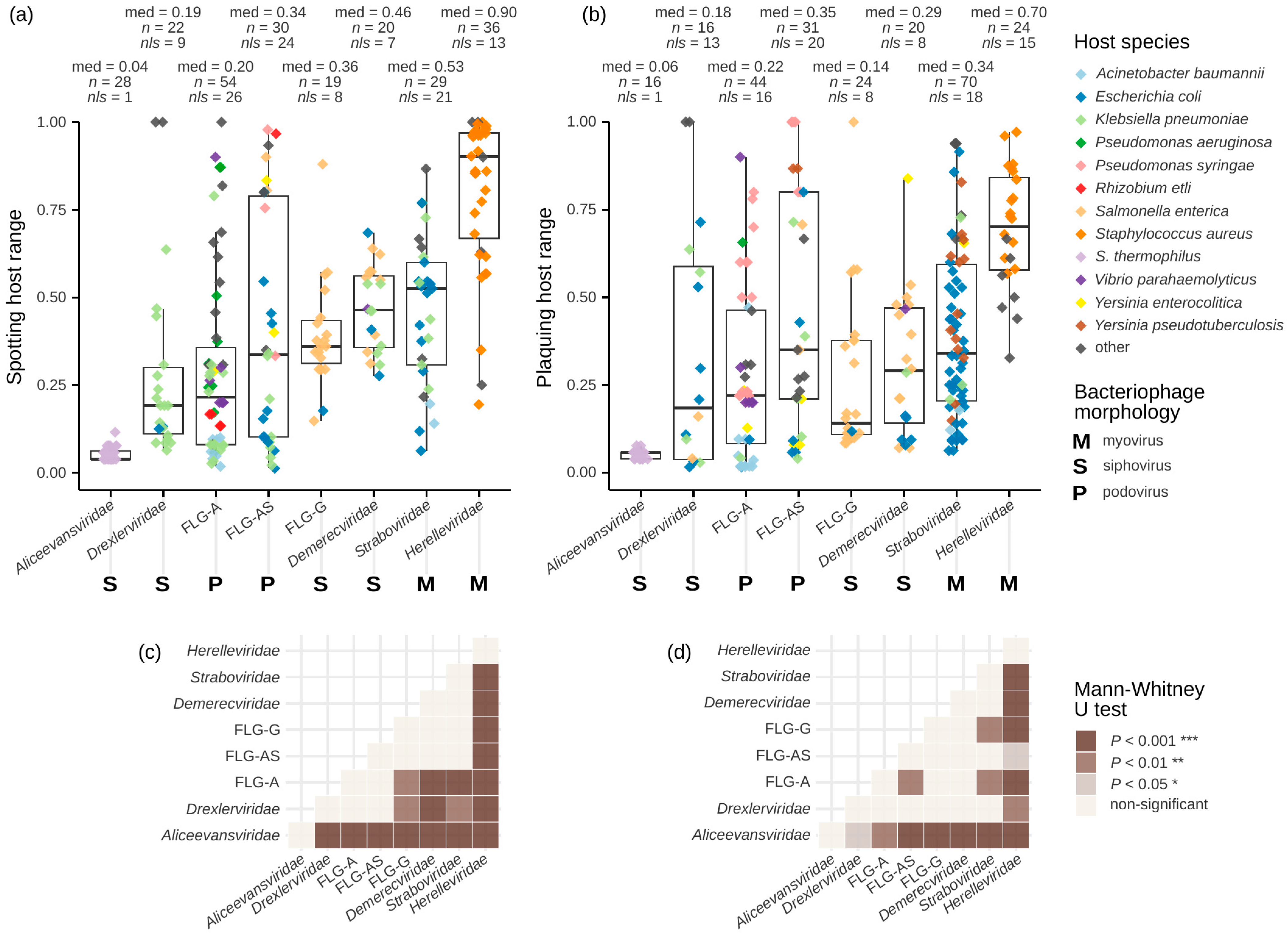

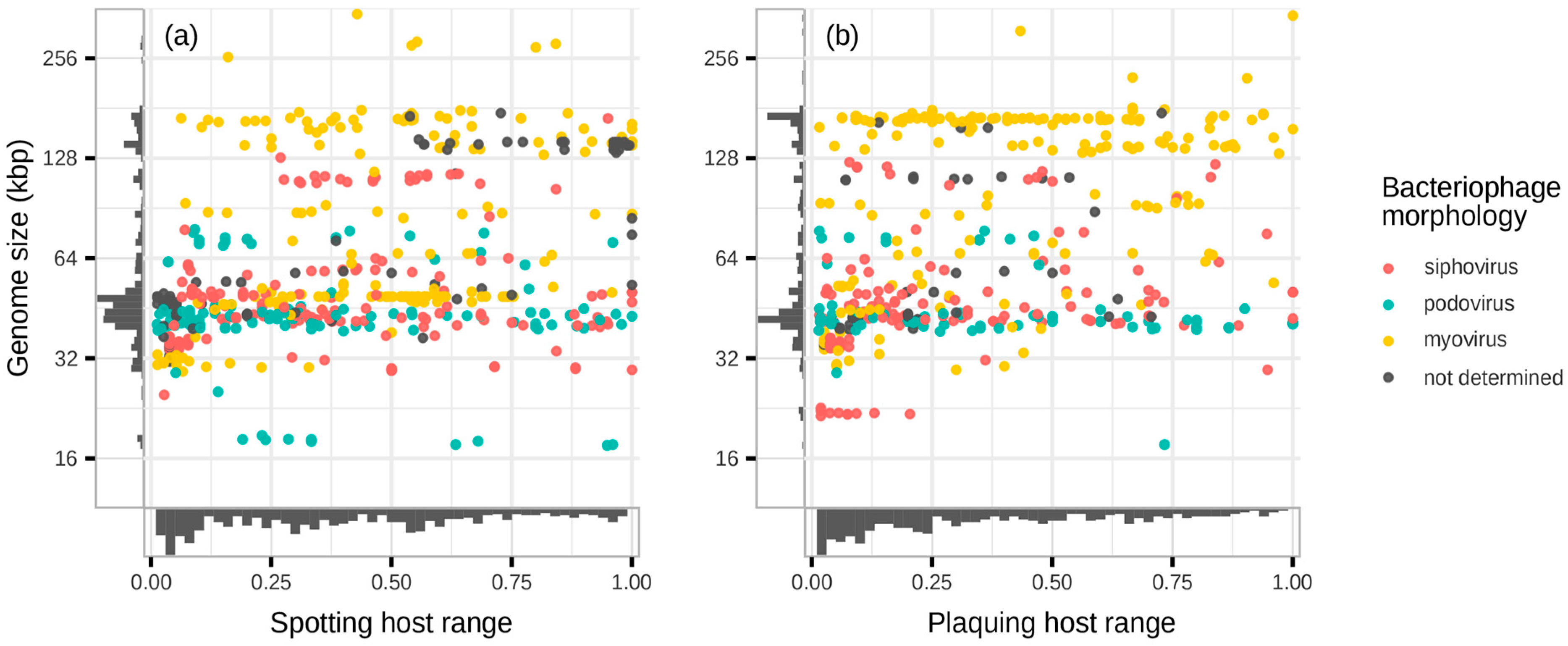

3.4. Host Ranges Differ Between Taxonomic Groups

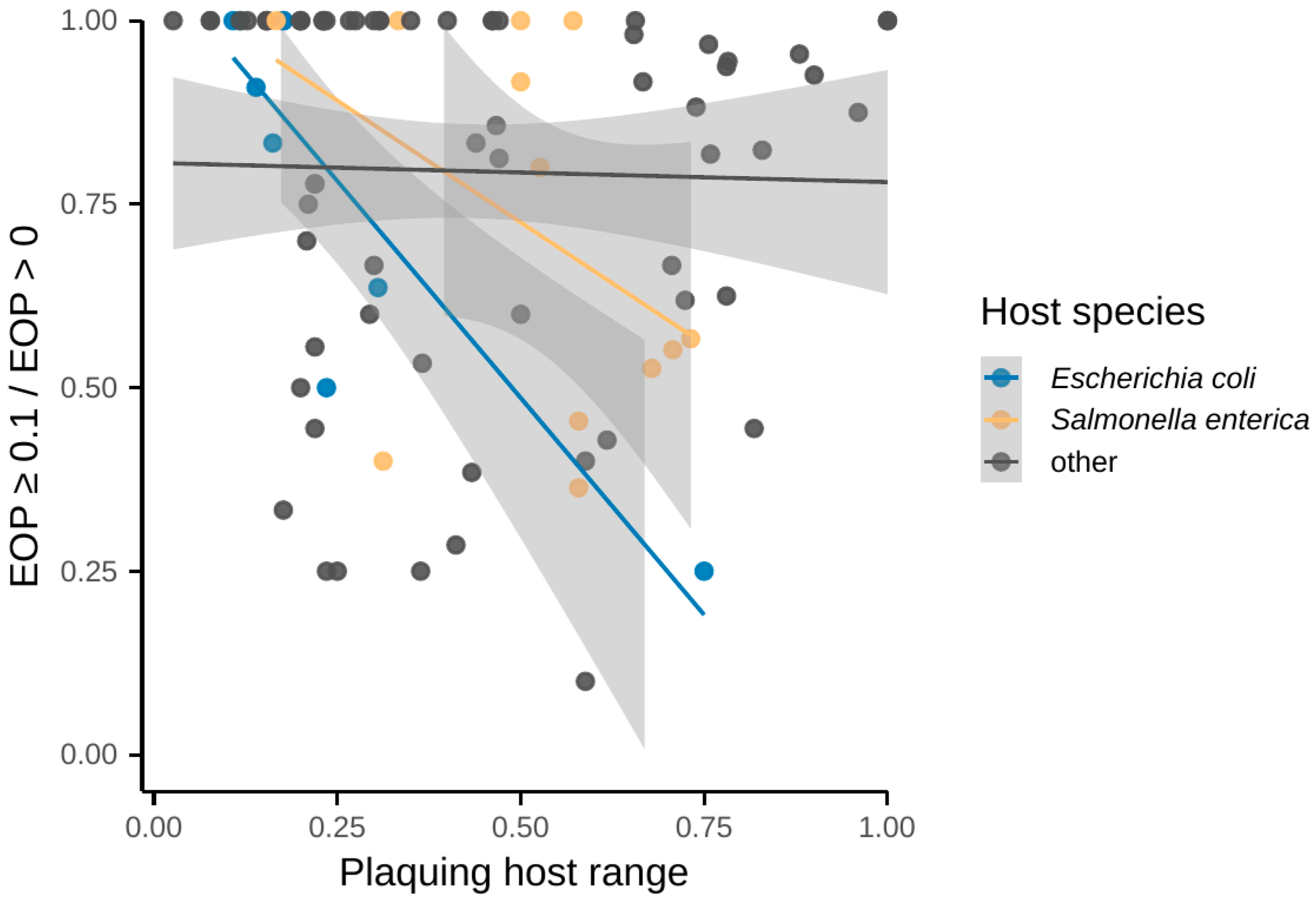

3.5. Taxonomy of Phages and Hosts Was the Only Identified Factor, Correlating with Host Ranges

3.6. Methodological Limitations and Reliability of the Study

4. Questions for Further Studies

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turner, D.; Kropinski, A.M.; Adriaenssens, E.M. A Roadmap for Genome-Based Phage Taxonomy. Viruses 2021, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dion, M.B.; Oechslin, F.; Moineau, S. Phage diversity, genomics and phylogeny. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrycht, K.; Rynkiewicz, A.A.; Harasymczuk, M.; Barylski, J.; Zielezinski, A. Daily Reports on Phage-Host Interactions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 946070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, C.A.; Marston, M.F.; Martiny, J.B. Biogeographic variation in host range phenotypes and taxonomic composition of marine cyanophage isolates. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayers, K.M.J.; Kuhlisch, C.; Basso, J.T.R.; Saltvedt, M.R.; Buchan, A.; Sandaa, R.A. Grazing on marine viruses and its biogeochemical implications. mBio 2023, 14, e0192121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambalavanan, L.; Iehata, S.; Fletcher, R.; Stevens, E.H.; Zainathan, S.C. A Review of marine viruses in coral ecosystem. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, S.A.; Tikhonova, I.V.; Krasnopeev, A.Y.; Kabilov, M.R.; Tupikin, A.E.; Chebunina, N.S.; Zhuchenko, N.A.; Belykh, O.I. Metagenomic analysis of virioplankton from the pelagic zone of lake Baikal. Viruses 2019, 11, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, P.; Buckling, A. Bacteria-phage antagonistic coevolution in soil. Science 2011, 332, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriaenssens, E.M.; Kramer, R.; Van Goethem, M.W.; Makhalanyane, T.P.; Hogg, I.; Cowan, D.A. Environmental drivers of viral community composition in Antarctic soils identified by viromics. Microbiome 2017, 5, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grasis, J.A.; Lachnit, T.; Anton-Erxleben, F.; Lim, Y.W.; Schmieder, R.; Fraune, S.; Franzenburg, S.; Insua, S.; Machado, G.; Haynes, M.; et al. Species-specific viromes in the ancestral holobiont Hydra. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, J.M.; Brzozowski, R.S.; Faith, D.; Round, J.L.; Secor, P.R.; Duerkop, B.A. Bacteriophage-bacteria interactions in the gut: From invertebrates to mammals. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2021, 8, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirnay, J.P.; Blasdel, B.G.; Bretaudeau, L.; Buckling, A.; Chanishvili, N.; Clark, J.R.; Corte-Real, S.; Debarbieux, L.; Dublanchet, A.; De Vos, D.; et al. Quality and safety requirements for sustainable phage therapy products. Pharm. Res. 2015, 32, 2173–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endersen, L.; Coffey, A. The use of bacteriophages for food safety. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2020, 36, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagemans, J.; Holtappels, D.; Vainio, E.; Rabiey, M.; Marzachì, C.; Herrero, S.; Ravanbakhsh, M.; Tebbe, C.C.; Ogliastro, M.; Ayllón, M.A.; et al. Going Viral: Virus-Based Biological Control Agents for Plant Protection. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2022, 60, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desiree, K.; Mosimann, S.; Ebner, P. Efficacy of phage therapy in pigs: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skab157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łos, M.; Czyz, A.; Sell, E.; Wegrzyn, A.; Neubauer, P.; Wegrzyn, G. Bacteriophage contamination: Is. there a simple method to reduce its deleterious effects in laboratory cultures and biotechnological factories? J. Appl. Genet. 2004, 45, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Romero, D.A.; Magill, D.; Millen, A.; Horvath, P.; Fremaux, C. Dairy lactococcal and streptococcal phage-host interactions: An industrial perspective in an evolving phage landscape. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2020, 44, 909–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura de Sousa, J.A.; Pfeifer, E.; Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P.C. Causes and Consequences of Bacteriophage Diversification via Genetic Exchanges across Lifestyles and Bacterial Taxa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 2497–2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommers, P.; Chatterjee, A.; Varsani, A.; Trubl, G. Integrating Viral Metagenomics into an Ecological Framework. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2021, 8, 133–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, P.; Abedon, S.T. Bacteriophage host range and bacterial resistance. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 70, 217–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, Z.; Abedon, S.T. Diversity of phage infection types and associated terminology: The problem with ‘Lytic or lysogenic’. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, fnw047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jonge, P.A.; Nobrega, F.L.; Brouns, S.J.J.; Dutilh, B.E. Molecular and Evolutionary Determinants of Bacteriophage Host Range. Trends Microbiol. 2019, 27, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtappels, D.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P.; Koskella, B. Drivers and consequences of bacteriophage host range. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, E.; van Sinderen, D.; Mahony, J. In Vitro Characteristics of Phages to Guide ‘Real Life’ Phage Therapy Suitability. Viruses 2018, 10, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glonti, T.; Pirnay, J.P. In Vitro Techniques and Measurements of Phage Characteristics That Are Important for Phage Therapy Success. Viruses 2022, 14, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyman, P. Phages for Phage Therapy: Isolation, Characterization, and Host Range Breadth. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yerushalmy, O.; Braunstein, R.; Alkalay-Oren, S.; Rimon, A.; Coppenhagn-Glazer, S.; Onallah, H.; Nir-Paz, R.; Hazan, R. Towards Standardization of Phage Susceptibility Testing: The Israeli Phage Therapy Center “Clinical Phage Microbiology”-A Pipeline Proposal. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77 (Suppl. S5), S337–S351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, E.M.; Gorman, S.P.; Donnelly, R.F.; Gilmore, B.F. Recent advances in bacteriophage therapy: How delivery routes, formulation, concentration and timing influence the success of phage therapy. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011, 63, 1253–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dąbrowska, K.; Abedon, S.T. Pharmacologically Aware Phage Therapy: Pharmacodynamic and Pharmacokinetic Obstacles to Phage Antibacterial Action in Animal and Human Bodies. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2019, 83, e00012–e00019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattila, S.; Ruotsalainen, P.; Jalasvuori, M. On-Demand Isolation of Bacteriophages Against Drug-Resistant Bacteria for Personalized Phage Therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.; Ward, S.; Hyman, P. More Is Better: Selecting for Broad Host Range Bacteriophages. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allué-Guardia, A.; Saranathan, R.; Chan, J.; Torrelles, J.B. Mycobacteriophages as Potential Therapeutic Agents against Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Andrea, M.M.; Frezza, D.; Romano, E.; Marmo, P.; Henrici De Angelis, L.; Perini, N.; Thaller, M.C.; Di Lallo, G. The lytic bacteriophage vB_EfaH_EF1TV, a new member of the Herelleviridae family, disrupts biofilm produced by Enterococcus faecalis clinical strains. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 21, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo-Moreno, S.; Buttimer, C.; Bottacini, F.; Chanishvili, N.; Ross, P.; Hill, C.; Coffey, A. Insights into Gene Transcriptional Regulation of Kayvirus Bacteriophages Obtained from Therapeutic Mixtures. Viruses 2022, 14, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkachev, P.V.; Pchelin, I.M.; Azarov, D.V.; Gorshkov, A.N.; Shamova, O.V.; Dmitriev, A.V.; Goncharov, A.E. Two Novel Lytic Bacteriophages Infecting Enterococcus spp. Are Promising Candidates for Targeted Antibacterial Therapy. Viruses 2022, 14, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolenda, C.; Medina, M.; Bonhomme, M.; Laumay, F.; Roussel-Gaillard, T.; Martins-Simoes, P.; Tristan, A.; Pirot, F.; Ferry, T.; Laurent, F.; et al. Phage Therapy against Staphylococcus aureus: Selection and Optimization of Production Protocols of Novel Broad-Spectrum Silviavirus Phages. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolas, M.; Trotereau, A.; Culot, A.; Moodley, A.; Atterbury, R.; Wagemans, J.; Lavigne, R.; Velge, P.; Schouler, C. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Phage Collection against Avian-Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0429622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, D.W.; Hudson, L.K.; Wang, J.; Denes, T.G. Characterization of a Diverse Collection of Salmonella Phages Isolated from Tennessee Wastewater. Phage 2023, 4, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summer, E.J.; Liu, M.; Gill, J.J.; Grant, M.; Chan-Cortes, T.N.; Ferguson, L.; Janes, C.; Lange, K.; Bertoli, M.; Moore, C.; et al. Genomic and functional analyses of Rhodococcus equi phages ReqiPepy6, ReqiPoco6, ReqiPine5, and ReqiDocB7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, S.E.; Lo, H.H.; Chen, S.T.; Lee, M.C.; Tseng, Y.H. Wide host range and strong lytic activity of Staphylococcus aureus lytic phage Stau2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monson, R.; Foulds, I.; Foweraker, J.; Welch, M.; Salmond, G.P.C. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa generalized transducing phage phiPA3 is a new member of the phiKZ-like group of ‘jumbo’ phages, and infects model laboratory strains and clinical isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Microbiology 2011, 157 Pt 3, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceyssens, P.J.; Glonti, T.; Kropinski, N.M.; Lavigne, R.; Chanishvili, N.; Kulakov, L.; Lashkhi, N.; Tediashvili, M.; Merabishvili, M. Phenotypic and genotypic variations within a single bacteriophage species. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekulovic, O.; Meessen-Pinard, M.; Fortier, L.C. Prophage-stimulated toxin production in Clostridium difficile NAP1/027 lysogens. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 2726–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooton, S.P.; Atterbury, R.J.; Connerton, I.F. Application of a bacteriophage cocktail to reduce Salmonella Typhimurium U288 contamination on pig skin. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 151, 157–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandersteegen, K.; Mattheus, W.; Ceyssens, P.J.; Bilocq, F.; De Vos, D.; Pirnay, J.P.; Noben, J.P.; Merabishvili, M.; Lipinska, U.; Hermans, K.; et al. Microbiological and molecular assessment of bacteriophage ISP for the control of Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatek, M.; Parasion, S.; Mizak, L.; Gryko, R.; Bartoszcze, M.; Kocik, J. Characterization of a bacteriophage, isolated from a cow with mastitis, that is lytic against Staphylococcus aureus strains. Arch. Virol. 2012, 157, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maura, D.; Morello, E.; du Merle, L.; Bomme, P.; Le Bouguénec, C.; Debarbieux, L. Intestinal colonization by enteroaggregative Escherichia coli supports long-term bacteriophage replication in mice. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 14, 1844–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, I.; Lurz, R.; Geider, K. Tasmancin and lysogenic bacteriophages induced from Erwinia tasmaniensis strains. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 167, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, A.V.; Zhilenkov, E.L.; Myakinina, V.P.; Krasilnikova, V.M.; Volozhantsev, N.V. Isolation and characterization of wide host range lytic bacteriophage AP22 infecting Acinetobacter baumannii. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2012, 332, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Gao, M.; Wu, D.; Liu, P.; Wu, Y. Genome characteristics of a novel phage from Bacillus thuringiensis showing high similarity with phage from Bacillus cereus. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Hezwani, M.; Nelson, S.; Salisbury, V.; Reynolds, D. Characterization of the Salmonella bacteriophage vB_SenS-Ent1. J. Gen. Virol. 2012, 93 Pt 9, 2046–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraushaar, B.; Thanh, M.D.; Hammerl, J.A.; Reetz, J.; Fetsch, A.; Hertwig, S. Isolation and characterization of phages with lytic activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains belonging to clonal complex 398. Arch. Virol. 2013, 158, 2341–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Shin, H.; Heu, S.; Ryu, S. Characterization and complete genome sequence analysis of Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophage SA12. Virus Genes 2013, 47, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Liu, W.; Zou, L.; Yan, C.; Lu, K.; Ren, H. T4-like phage Bp7, a potential antimicrobial agent for controlling drug-resistant Escherichia coli in chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5559–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.; Yun, J.; Lim, J.A.; Roh, E.; Jung, K.S.; Chang, Y.; Ryu, S.; Heu, S. Characterization and genomic analysis of two Staphylococcus aureus bacteriophages isolated from poultry/livestock farms. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94 Pt 11, 2569–2576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakhetia, R.; Talukder, K.A.; Verma, N.K. Isolation, characterization and comparative genomics of bacteriophage SfIV: A novel serotype converting phage from Shigella flexneri. BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaría, R.I.; Bustos, P.; Sepúlveda-Robles, O.; Lozano, L.; Rodríguez, C.; Fernández, J.L.; Juárez, S.; Kameyama, L.; Guarneros, G.; Dávila, G.; et al. Narrow-host-range bacteriophages that infect Rhizobium etli associate with distinct genomic types. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, L.D.R.; Sillankorva, S.; Ackermann, H.W.; Kropinski, A.M.; Azeredo, J.; Cerca, N. Isolation and characterization of a new Staphylococcus epidermidis broad-spectrum bacteriophage. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95 Pt 2, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Kim, S.; Park, B.; Ryu, S. Core lipopolysaccharide-specific phage SSU5 as an Auxiliary Component of a Phage Cocktail for Salmonella biocontrol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1026–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanagh, D.; Guinane, C.M.; Neve, H.; Coffey, A.; Ross, R.P.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; McAuliffe, O. Phages of non-dairy lactococci: Isolation and characterization of ΦL47, a phage infecting the grass isolate Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris DPC6860. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 4, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frampton, R.A.; Taylor, C.; Holguín Moreno, A.V.; Visnovsky, S.B.; Petty, N.K.; Pitman, A.R.; Fineran, P.C. Identification of bacteriophages for biocontrol of the kiwifruit canker phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2216–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.; Gram, L.; Middelboe, M. Vibriophages and their interactions with the fish pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3128–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baugher, J.L.; Durmaz, E.; Klaenhammer, T.R. Spontaneously induced prophages in Lactobacillus gasseri contribute to horizontal gene transfer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3508–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbasifar, R.; Kropinski, A.M.; Sabour, P.M.; Chambers, J.R.; MacKinnon, J.; Malig, T.; Griffiths, M.W. Efficiency of bacteriophage therapy against Cronobacter sakazakii in Galleria mellonella (greater wax moth) larvae. Arch. Virol. 2014, 159, 2253–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lallo, G.; Evangelisti, M.; Mancuso, F.; Ferrante, P.; Marcelletti, S.; Tinari, A.; Superti, F.; Migliore, L.; D’Addabbo, P.; Frezza, D.; et al. Isolation and partial characterization of bacteriophages infecting Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae, causal agent of kiwifruit bacterial canker. J. Basic Microbiol. 2014, 54, 1210–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merabishvili, M.; Vandenheuvel, D.; Kropinski, A.M.; Mast, J.; De Vos, D.; Verbeken, G.; Noben, J.P.; Lavigne, R.; Vaneechoutte, M.; Pirnay, J.P. Characterization of newly isolated lytic bacteriophages active against Acinetobacter baumannii. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, D.R.; Gaudion, A.; Bean, J.E.; Perez Esteban, P.; Arnot, T.C.; Harper, D.R.; Kot, W.; Hansen, L.H.; Enright, M.C.; Jenkins, A.T. Combined use of bacteriophage K and a novel bacteriophage to reduce Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 6694–6703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janež, N.; Kokošin, A.; Zaletel, E.; Vranac, T.; Kovač, J.; Vučković, D.; Smole Možina, S.; Curin Šerbec, V.; Zhang, Q.; Accetto, T.; et al. Identification and characterisation of new Campylobacter group III phages of animal origin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 359, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakhetia, R.; Marri, A.; Ståhle, J.; Widmalm, G.; Verma, N.K. Serotype-conversion in Shigella flexneri: Identification of a novel bacteriophage, Sf101, from a serotype 7a strain. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon-Velarde, C.G.; Kropinski, A.M.; Chen, S.; Abbasifar, A.; Griffiths, M.W.; Odumeru, J.A. Complete genome sequence of bacteriophage vB_YenP_AP5 which infects Yersinia enterocolitica of serotype O:3. Virol. J. 2014, 11, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, M.; Virtanen, S.; Korkeala, H.; Skurnik, M. Isolation and characterization of Yersinia-specific bacteriophages from pig stools in Finland. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 118, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, M.; Ryu, S. Bacteriophage PBC1 and its endolysin as an antimicrobial agent against Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 2274–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagonenko, A.L.; Sadovskaya, O.; Valentovich, L.N.; Evtushenkov, A.N. Characterization of a new ViI-like Erwinia amylovora bacteriophage phiEa2809. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362, fnv031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olszak, T.; Zarnowiec, P.; Kaca, W.; Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.; Augustyniak, D.; Drevinek, P.; de Soyza, A.; McClean, S.; Drulis-Kawa, Z. In vitro and in vivo antibacterial activity of environmental bacteriophages against Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from cystic fibrosis patients. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 6021–6033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan Mirzaei, M.; Nilsson, A.S. Isolation of phages for phage therapy: A comparison of spot tests and efficiency of plating analyses for determination of host range and efficacy. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, H.; Maciejewska, B.; Latka, A.; Majkowska-Skrobek, G.; Hellstrand, M.; Melefors, Ö.; Wang, J.T.; Kropinski, A.M.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; Nilsson, A.S. A suggested new bacteriophage genus, “Kp34likevirus”, within the Autographivirinae subfamily of Podoviridae. Viruses 2015, 7, 1804–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krasowska, A.; Biegalska, A.; Augustyniak, D.; Łoś, M.; Richert, M.; Łukaszewicz, M. Isolation and Characterization of Phages Infecting Bacillus subtilis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 179597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, D.L.; Lynch, K.H.; Stothard, P.; Dennis, J.J. The isolation and characterization of two Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteriophages capable of cross-taxonomic order infectivity. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Bao, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, R. Isolation and Characterization of Lytic Phage vB_EcoM_JS09 against Clinically Isolated Antibiotic-Resistant Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli and Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Intervirology 2015, 58, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eraclio, G.; Tremblay, D.M.; Lacelle-Côté, A.; Labrie, S.J.; Fortina, M.G.; Moineau, S. A virulent phage infecting Lactococcus garvieae, with homology to Lactococcus lactis phages. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 8358–8365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chang, Y.; Shin, H.; Lee, J.H.; Park, C.J.; Paik, S.Y.; Ryu, S. Isolation and Genome Characterization of the Virulent Staphylococcus aureus Bacteriophage SA97. Viruses 2015, 7, 5225–5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimoliūnas, E.; Vilkaitytė, M.; Kaliniene, L.; Zajančkauskaitė, A.; Kaupinis, A.; Staniulis, J.; Valius, M.; Meškys, R.; Truncaitė, L. Incomplete LPS Core-Specific Felix01-Like Virus vB_EcoM_VpaE1. Viruses 2015, 7, 6163–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Chen, M.; He, L.; Zhang, S.; Ding, T.; Yao, H.; Lu, C.; Zhang, W. Isolation and characterization of a T4-like phage with a relatively wide host range within Escherichia coli. J. Basic Microbiol. 2016, 56, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Xu, J.; Yao, H.; Lu, C.; Zhang, W. Isolation, genome sequencing and functional analysis of two T7-like coliphages of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Gene 2016, 582, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furusawa, T.; Iwano, H.; Higuchi, H.; Yokota, H.; Usui, M.; Iwasaki, T.; Tamura, Y. Bacteriophage can lyse antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from canine diseases. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2016, 78, 1035–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rombouts, S.; Volckaert, A.; Venneman, S.; Declercq, B.; Vandenheuvel, D.; Allonsius, C.N.; Van Malderghem, C.; Jang, H.B.; Briers, Y.; Noben, J.P.; et al. Characterization of Novel Bacteriophages for Biocontrol of Bacterial Blight in Leek Caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. porri. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.; Ryu, C.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Park, J.H.; Yong, D.; Lee, K. In Vivo Application of Bacteriophage as a Potential Therapeutic Agent To Control OXA-66-Like Carbapenemase-Producing Acinetobacter baumannii Strains Belonging to Sequence Type 357. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 4200–4208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Zeng, Z.; Mai, K.; Yang, Y.; Feng, J.; Bai, Y.; Sun, B.; Xie, Q.; Tong, Y.; Ma, J. Preliminary treatment of bovine mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus, with trx-SA1, recombinant endolysin of, S. aureus bacteriophage IME-SA1. Vet. Microbiol. 2016, 191, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurczak-Kurek, A.; Gąsior, T.; Nejman-Faleńczyk, B.; Bloch, S.; Dydecka, A.; Topka, G.; Necel, A.; Jakubowska-Deredas, M.; Narajczyk, M.; Richert, M.; et al. Biodiversity of bacteriophages: Morphological and biological properties of a large group of phages isolated from urban sewage. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, C.; Moreirinha, C.; Lewicka, M.; Almeida, P.; Clemente, C.; Romalde, J.L.; Nunes, M.L.; Almeida, A. Characterization and in vitro evaluation of new bacteriophages for the biocontrol of Escherichia coli. Virus Res. 2017, 227, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, S.J.; Barylski, J.; Hargreaves, K.R.; Millard, A.A.; Vinner, G.K.; Clokie, M.R. Two Novel Myoviruses from the North of Iraq Reveal Insights into Clostridium difficile Phage Diversity and Biology. Viruses 2016, 8, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahony, J.; Oliveira, J.; Collins, B.; Hanemaaijer, L.; Lugli, G.A.; Neve, H.; Ventura, M.; Kouwen, T.R.; Cambillau, C.; van Sinderen, D. Genetic and functional characterisation of the lactococcal P335 phage-host interactions. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Wand, M.E.; Briers, Y.; Lavigne, R.; Sutton, J.M.; Reynolds, D.M. Characterisation and genome sequence of the lytic Acinetobacter baumannii bacteriophage vB_AbaS_Loki. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, D.L.; Stothard, P.; Dennis, J.J. The isolation and characterization of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia T4-like bacteriophage DLP6. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endersen, L.; Buttimer, C.; Nevin, E.; Coffey, A.; Neve, H.; Oliveira, H.; Lavigne, R.; O’Mahony, J. Investigating the biocontrol and anti-biofilm potential of a three phage cocktail against Cronobacter sakazakii in different brands of infant formula. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 253, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amgarten, D.; Martins, L.F.; Lombardi, K.C.; Antunes, L.P.; de Souza, A.P.S.; Nicastro, G.G.; Kitajima, E.W.; Quaggio, R.B.; Upton, C.; Setubal, J.C.; et al. Three novel Pseudomonas phages isolated from composting provide insights into the evolution and diversity of tailed phages. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, C.; Yang, J.; Lu, Z.; Lu, F.; Bie, X. Characterization of a broad host-spectrum virulent Salmonella bacteriophage fmb-p1 and its application on duck meat. Virus Res. 2017, 236, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalatzis, P.G.; Rørbo, N.I.; Castillo, D.; Mauritzen, J.J.; Jørgensen, J.; Kokkari, C.; Zhang, F.; Katharios, P.; Middelboe, M. Stumbling across the Same Phage: Comparative Genomics of Widespread Temperate Phages Infecting the Fish Pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Viruses 2017, 9, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, L.; Gong, P.; Cai, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Ge, J.; Ji, Y.; et al. The Bacteriophage EF-P29 Efficiently Protects against Lethal Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus faecalis and Alleviates Gut Microbiota Imbalance in a Murine Bacteremia Model. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, A.V.; Lavysh, D.G.; Klimuk, E.I.; Edelstein, M.V.; Bogun, A.G.; Shneider, M.M.; Goncharov, A.E.; Leonov, S.V.; Severinov, K.V. Novel Fri1-like Viruses Infecting Acinetobacter baumannii-vB_AbaP_AS11 and vB_AbaP_AS12-Characterization, Comparative Genomic Analysis, and Host-Recognition Strategy. Viruses 2017, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abatángelo, V.; Peressutti Bacci, N.; Boncompain, C.A.; Amadio, A.F.; Carrasco, S.; Suárez, C.A.; Morbidoni, H.R. Broad-range lytic bacteriophages that kill Staphylococcus aureus local field strains. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, A.T.; Paquet, V.E.; Bernatchez, A.; Tremblay, D.M.; Moineau, S.; Charette, S.J. Characterization and diversity of phages infecting Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amarillas, L.; Rubí-Rangel, L.; Chaidez, C.; González-Robles, A.; Lightbourn-Rojas, L.; León-Félix, J. Isolation and Characterization of phiLLS, a Novel Phage with Potential Biocontrol Agent against Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, P.; Tian, S.; Yuan, Z.; Hu, X. Identification and genomic comparison of temperate bacteriophages derived from emetic Bacillus cereus. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, H.; Costa, A.R.; Konstantinides, N.; Ferreira, A.; Akturk, E.; Sillankorva, S.; Nemec, A.; Shneider, M.; Dötsch, A.; Azeredo, J. Ability of phages to infect Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-Acinetobacter baumannii complex species through acquisition of different pectate lyase depolymerase domains. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 5060–5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latz, S.; Krüttgen, A.; Häfner, H.; Buhl, E.M.; Ritter, K.; Horz, H.P. Differential Effect of Newly Isolated Phages Belonging to PB1-Like, phiKZ-Like and LUZ24-Like Viruses against Multi-Drug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa under Varying Growth Conditions. Viruses 2017, 9, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Park, M.K. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Broad-host-range Bacteriophage Infecting Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica for Biocontrol and Rapid Detection. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 2151–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, K.; LaBossiere, B.; Switt, A.I.M.; Delaquis, P.; Goodridge, L.; Levesque, R.C.; Danyluk, M.D.; Wang, S. Characterization of Four Novel Bacteriophages Isolated from British Columbia for Control of Non-typhoidal Salmonella in Vitro and on Sprouting Alfalfa Seeds. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katharios, P.; Kalatzis, P.G.; Kokkari, C.; Sarropoulou, E.; Middelboe, M. Isolation and characterization of a N4-like lytic bacteriophage infecting Vibrio splendidus, a pathogen of fish and bivalves. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0190083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelle, K.; Murphy, J.; Fitzgerald, B.; Lugli, G.A.; Zomer, A.; Neve, H.; Ventura, M.; Franz, C.M.; Cambillau, C.; van Sinderen, D.; et al. A Decade of Streptococcus thermophilus Phage Evolution in an Irish Dairy Plant. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02855-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, L.D.R.; Brandão, A.; Akturk, E.; Santos, S.B.; Azeredo, J. Characterization of a New Staphylococcus aureus Kayvirus Harboring a Lysin Active against Biofilms. Viruses 2018, 10, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajuebor, J.; Buttimer, C.; Arroyo-Moreno, S.; Chanishvili, N.; Gabriel, E.M.; O’Mahony, J.; McAuliffe, O.; Neve, H.; Franz, C.; Coffey, A. Comparison of Staphylococcus Phage K with Close Phage Relatives Commonly Employed in Phage Therapeutics. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, K.; Senevirathne, A.; Kang, H.S.; Hyun, W.B.; Kim, J.E.; Kim, K.P. Complete Nucleotide Sequence Analysis of a Novel Bacillus subtilis-Infecting Bacteriophage BSP10 and Its Effect on Poly-Gamma-Glutamic Acid Degradation. Viruses 2018, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sváb, D.; Falgenhauer, L.; Rohde, M.; Chakraborty, T.; Tóth, I. Identification and characterization of new broad host-range rV5-like coliphages C203 and P206 directed against enterobacteria. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 64, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewska-Jeznach, M.; Bardowski, J.K.; Szczepankowska, A.K. Molecular, physiological and phylogenetic traits of Lactococcus 936-type phages from distinct dairy environments. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, H.M.; Duc, H.M.; Masuda, Y.; Honjoh, K.I.; Miyamoto, T. Application of bacteriophages in simultaneously controlling Escherichia coli O157:H7 and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 10259–10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavelle, K.; Martinez, I.; Neve, H.; Lugli, G.A.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Ventura, M.; Bello, F.D.; Sinderen, D.V.; Mahony, J. Biodiversity of Streptococcus thermophilus Phages in Global Dairy Fermentations. Viruses 2018, 10, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newase, S.; Kapadnis, B.P.; Shashidhar, R. Isolation and Genome Sequence Characterization of Bacteriophage vB_SalM_PM10, a Cba120virus, Concurrently Infecting Salmonella enterica Serovars Typhimurium, Typhi, and Enteritidis. Curr. Microbiol. 2019, 76, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, P.; Wan, X.; Cheng, J.; Yuan, Z.; Hu, X. vB_LspM-01: A novel myovirus displaying pseudolysogeny in Lysinibacillus sphaericus C3-41. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 10691–10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Lim, J.A.; Yu, J.G.; Oh, C.S. Genomic Features and Lytic Activity of the Bacteriophage PPPL-1 Effective against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae, a Cause of Bacterial Canker in Kiwifruit. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 28, 1542–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandare, S.; Colom, J.; Baig, A.; Ritchie, J.M.; Bukhari, H.; Shah, M.A.; Sarkar, B.L.; Su, J.; Wren, B.; Barrow, P.; et al. Reviving Phage Therapy for the Treatment of Cholera. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 219, 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Xu, J.; Yu, X.; Huang, X.; Liu, G.; Liu, X. Identification of novel bacteriophage vB_EcoP-EG1 with lytic activity against planktonic and biofilm forms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Geagea, H.; Rousseau, G.M.; Labrie, S.J.; Tremblay, D.M.; Liu, X.; Moineau, S. Characterization of the Escherichia coli Virulent Myophage ST32. Viruses 2018, 10, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, H.; Costa, A.R.; Ferreira, A.; Konstantinides, N.; Santos, S.B.; Boon, M.; Noben, J.P.; Lavigne, R.; Azeredo, J. Functional Analysis and Antivirulence Properties of a New Depolymerase from a Myovirus That Infects Acinetobacter baumannii Capsule K45. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e01163-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moodley, A.; Kot, W.; Nälgård, S.; Jakociune, D.; Neve, H.; Hansen, L.H.; Guardabassi, L.; Vogensen, F.K. Isolation and characterization of bacteriophages active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 122, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; von Mentzer, A.; Begum, Y.A.; Manzur, M.; Hasan, M.; Ghosh, A.N.; Hossain, M.A.; Camilli, A.; Qadri, F. Phenotypic and genomic analyses of bacteriophages targeting environmental and clinical CS3-expressing enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0209357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Wang, H.; Ma, H.; Bao, R.; Liu, H.; Yang, L.; Liang, B.; Jia, L.; Xie, J.; Xiang, Y.; et al. Characterization and Genomic Analysis of SFPH2, a Novel T7virus Infecting Shigella. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazimierczak, J.; Wójcik, E.A.; Witaszewska, J.; Guziński, A.; Górecka, E.; Stańczyk, M.; Kaczorek, E.; Siwicki, A.K.; Dastych, J. Complete genome sequences of Aeromonas and Pseudomonas phages as a supportive tool for development of antibacterial treatment in aquaculture. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Xing, S.; Fu, K.; Zhao, S.; Liu, J.; Tong, Y.; Zhou, L. Genomic and biological characterization of the Vibrio alginolyticus-infecting “Podoviridae” bacteriophage, vB_ValP_IME271. Virus Genes 2019, 55, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Qu, K.; Tan, D.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Cong, C.; Xiu, Z.; Xu, Y. Isolation and characterization of a bacteriophage and its potential to disrupt multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 128, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topka, G.; Bloch, S.; Nejman-Faleńczyk, B.; Gąsior, T.; Jurczak-Kurek, A.; Necel, A.; Dydecka, A.; Richert, M.; Węgrzyn, G.; Węgrzyn, A. Characterization of Bacteriophage vB-EcoS-95, Isolated From Urban Sewage and Revealing Extremely Rapid Lytic Development. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, I.Y.; Lee, C.; Song, W.K.; Jang, S.J.; Park, M.K. Lytic KFS-SE2 phage as a novel bio-receptor for Salmonella Enteritidis detection. J. Microbiol. 2019, 57, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.J.; Lin, T.L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Lai, P.H.; Tsai, Y.T.; Hsu, C.R.; Hsieh, P.F.; Lin, Y.T.; Wang, J.T. Identification of three podoviruses infecting Klebsiella encoding capsule depolymerases that digest specific capsular types. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Głowacka-Rutkowska, A.; Gozdek, A.; Empel, J.; Gawor, J.; Żuchniewicz, K.; Kozińska, A.; Dębski, J.; Gromadka, R.; Łobocka, M. The Ability of Lytic Staphylococcal Podovirus vB_SauP_phiAGO1.3 to Coexist in Equilibrium With Its Host Facilitates the Selection of Host Mutants of Attenuated Virulence but Does Not Preclude the Phage Antistaphylococcal Activity in a Nematode Infection Model. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wei, X.; Li, H.; Lin, W.; Ke, Y.; Hu, L.; Jiang, A.; et al. Identification and molecular characterization of Serratia marcescens phages vB_SmaA_2050H1 and vB_SmaM_2050HW. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addy, H.S.; Ahmad, A.A.; Huang, Q. Molecular and Biological Characterization of Ralstonia Phage RsoM1USA, a New Species of P2virus, Isolated in the United States. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrowes, B.H.; Molineux, I.J.; Fralick, J.A. Directed in Vitro Evolution of Therapeutic Bacteriophages: The Appelmans Protocol. Viruses. 2019, 11, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gencay, Y.E.; Gambino, M.; Prüssing, T.F.; Brøndsted, L. The genera of bacteriophages and their receptors are the major determinants of host range. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 21, 2095–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, X.; Shi, Y.; Yin, S.; Shen, W.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; You, B.; Gong, Y.; et al. Characterization and genome annotation of a newly detected bacteriophage infecting multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 1527–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulgione, A.; Ianniello, F.; Papaianni, M.; Contaldi, F.; Sgamma, T.; Giannini, C.; Pastore, S.; Velotta, R.; Della Ventura, B.; Roveri, N.; et al. Biomimetic hydroxyapatite nanocrystals are an active carrier for Salmonella bacteriophages. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 2219–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.T.; Sun, X.; Quintela, I.A.; Bridges, D.F.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Salvador, A.; Wu, V.C.H. Discovery of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli (STEC)-Specific Bacteriophages From Non-fecal Composts Using Genomic Characterization. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, L.D.R.; Ferreira, R.; Costa, A.R.; Oliveira, H.; Azeredo, J. Efficacy and safety assessment of two enterococci phages in an in vitro biofilm wound model. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, F.P.; Xavier, A.D.S.; Bruckner, F.P.; de Rezende, R.R.; Vidigal, P.M.P.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P. Biological and molecular characterization of a bacteriophage infecting Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, isolated from brassica fields. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 1857–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korf, I.H.E.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Adriaenssens, E.M.; Kropinski, A.M.; Nimtz, M.; Rohde, M.; van Raaij, M.J.; Wittmann, J. Still Something to Discover: Novel Insights into Escherichia coli Phage Diversity and Taxonomy. Viruses 2019, 11, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phothaworn, P.; Dunne, M.; Supokaivanich, R.; Ong, C.; Lim, J.; Taharnklaew, R.; Vesaratchavest, M.; Khumthong, R.; Pringsulaka, O.; Ajawatanawong, P.; et al. Characterization of Flagellotropic, Chi-Like Salmonella Phages Isolated from Thai Poultry Farms. Viruses. 2019, 11, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Melo, A.C.C.; da Mata Gomes, A.; Melo, F.L.; Ardisson-Araújo, D.M.P.; de Vargas, A.P.C.; Ely, V.L.; Kitajima, E.W.; Ribeiro, B.M.; Wolff, J.L.C. Characterization of a bacteriophage with broad host range against strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from domestic animals. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, T.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, F.; Xie, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; et al. Characterization and genome analysis of novel Klebsiella phage Henu1 with lytic activity against clinical strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 2389–2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, J.; Melo, L.D.R.; Poeta, P.; Igrejas, G.; Ferraz, M.P.; Azeredo, J.; Monteiro, F.J. Lytic bacteriophages against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis and Escherichia coli isolates from orthopaedic implant-associated infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 54, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahin, K.; Bouzari, M.; Wang, R.; Yazdi, M. Prevalence and molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant Shigella species of food origins and their inactivation by specific lytic bacteriophages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 305, 108252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piligrimova, E.G.; Kazantseva, O.A.; Nikulin, N.A.; Shadrin, A.M. Bacillus Phage vB_BtS_B83 Previously Designated as a Plasmid May Represent a New Siphoviridae Genus. Viruses 2019, 11, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akturk, E.; Oliveira, H.; Santos, S.B.; Costa, S.; Kuyumcu, S.; Melo, L.D.R.; Azeredo, J. Synergistic Action of Phage and Antibiotics: Parameters to Enhance the Killing Efficacy Against Mono and Dual-Species Biofilms. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Hanawa, T.; Azam, A.H.; LeBlanc, C.; Ung, P.; Matsuda, T.; Onishi, H.; Miyanaga, K.; Tanji, Y. Silviavirus phage ϕMR003 displays a broad host range against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus of human origin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 7751–7765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, H.; Shahin, K.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, S.; Stefan, S.; Wang, R. Morphologic and genomic characterization of a broad host range Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum lytic phage vB_SPuM_SP116. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 136, 103659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Zubidi, M.; Widziolek, M.; Court, E.K.; Gains, A.F.; Smith, R.E.; Ansbro, K.; Alrafaie, A.; Evans, C.; Murdoch, C.; Mesnage, S.; et al. Identification of Novel Bacteriophages with Therapeutic Potential That Target Enterococcus faecalis. Infect. Immun. 2019, 87, e00512–e00519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sergueev, K.V.; Filippov, A.A.; Farlow, J.; Su, W.; Kvachadze, L.; Balarjishvili, N.; Kutateladze, M.; Nikolich, M.P. Correlation of Host Range Expansion of Therapeutic Bacteriophage Sb-1 with Allele State at a Hypervariable Repeat Locus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01209–e01219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, L.; Nime, I.; Liu, K.; Yan, T.; Wang, X.; Li, J. Application of a Phage Cocktail for Control of Salmonella in Foods and Reducing Biofilms. Viruses 2019, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, K.; Tremblay, D.M.; Delaquis, P.; Goodridge, L.; Levesque, R.C.; Moineau, S.; Suttle, C.A.; Wang, S. Diversity and Host Specificity Revealed by Biological Characterization and Whole Genome Sequencing of Bacteriophages Infecting Salmonella enterica. Viruses 2019, 11, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunstan, R.A.; Pickard, D.; Dougan, S.; Goulding, D.; Cormie, C.; Hardy, J.; Li, F.; Grinter, R.; Harcourt, K.; Yu, L.; et al. The flagellotropic bacteriophage YSD1 targets Salmonella Typhi with a Chi-like protein tail fibre. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 112, 1831–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaczorowska, J.; Casey, E.; Neve, H.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Noben, J.P.; Lugli, G.A.; Ventura, M.; Sinderen, D.V.; Mahony, J. A Quest of Great Importance-Developing a Broad Spectrum Escherichia coli Phage Collection. Viruses 2019, 11, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łubowska, N.; Grygorcewicz, B.; Kosznik-Kwaśnicka, K.; Zauszkiewicz-Pawlak, A.; Węgrzyn, A.; Dołęgowska, B.; Piechowicz, L. Characterization of the Three New Kayviruses and Their Lytic Activity Against Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, D.; Andersen, N.; Kalatzis, P.G.; Middelboe, M. Large Phenotypic and Genetic Diversity of Prophages Induced from the Fish Pathogen Vibrio anguillarum. Viruses 2019, 11, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi-Midani, A.; Kim, J.O.; Kim, J.H.; Lim, J.; Ryu, J.G.; Kim, M.K.; Choi, T.J. Potential use of newly isolated bacteriophage as a biocontrol against Acidovorax citrulli. Arch. Microbiol. 2020, 202, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacífico, C.; Hilbert, M.; Sofka, D.; Dinhopl, N.; Pap, I.J.; Aspöck, C.; Carriço, J.A.; Hilbert, F. Natural Occurrence of Escherichia coli-Infecting Bacteriophages in Clinical Samples. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, M.; Brown, N.; Clokie, M.; Yeasmin, M.; Tareq, T.M.; Baddam, R.; Azad, M.A.K.; Ghosh, A.N.; Ahmed, N.; Talukder, K.A. Prevalence of Shigella boydii in Bangladesh: Isolation and Characterization of a Rare Phage MK-13 That Can Robustly Identify Shigellosis Caused by Shigella boydii Type 1. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morozova, V.; Babkin, I.; Kozlova, Y.; Baykov, I.; Bokovaya, O.; Tikunov, A.; Ushakova, T.; Bardasheva, A.; Ryabchikova, E.; Zelentsova, E.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Klebsiella pneumoniae N4-like Bacteriophage KP8. Viruses 2019, 11, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeman, M.; Bárdy, P.; Vrbovská, V.; Roudnický, P.; Zdráhal, Z.; Růžičková, V.; Doškař, J.; Pantůček, R. New Genus Fibralongavirus in Siphoviridae Phages of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. Viruses 2019, 11, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essoh, C.; Vernadet, J.P.; Vergnaud, G.; Coulibaly, A.; Kakou-N’Douba, A.; N’Guetta, A.S.; Ouassa, T.; Pourcel, C. Characterization of sixteen Achromobacter xylosoxidans phages from Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, isolated on a single clinical strain. Arch. Virol. 2020, 165, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Wang, C.; Qiang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, P.; Pei, G.; Zhang, X.; Mi, Z.; Huang, Y.; Tong, Y.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Bacteriophage Infecting Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo-Calap, P.; Beamud, B.; Vienne, J.; González-Candelas, F.; Sanjuán, R. Isolation of Four Lytic Phages Infecting Klebsiella pneumoniae K22 Clinical Isolates from Spain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathieu, A.; Dion, M.; Deng, L.; Tremblay, D.; Moncaut, E.; Shah, S.A.; Stokholm, J.; Krogfelt, K.A.; Schjørring, S.; Bisgaard, H.; et al. Virulent coliphages in 1-year-old children fecal samples are fewer, but more infectious than temperate coliphages. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imklin, N.; Nasanit, R. Characterization of Salmonella bacteriophages and their potential use in dishwashing materials. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 129, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmielewska-Jeznach, M.; Bardowski, J.K.; Szczepankowska, A.K. LactococcusCeduovirus Phages Isolated from Industrial Dairy Plants-from Physiological to Genomic Analyses. Viruses 2020, 12, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Liang, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Ye, Y.; Gao, X.; Wu, Q.; Tan, Z. Isolation and Characterization of the Novel Phages vB_VpS_BA3 and vB_VpS_CA8 for Lysing Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Xie, X.; Tu, Z.; Gu, J.; Zhang, A. Characterization and whole-genome sequencing of broad-host-range Salmonella-specific bacteriophages for bio-control. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 143, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, Y.; Zhai, S.; Wang, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Xi, H.; Cai, R.; Zhao, R.; et al. The Yersinia Phage X1 Administered Orally Efficiently Protects a Murine Chronic Enteritis Model Against Yersinia enterocolitica Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaczek-Moczydłowska, M.A.; Young, G.K.; Trudgett, J.; Plahe, C.; Fleming, C.C.; Campbell, K.; O’ Hanlon, R. Phage cocktail containing Podoviridae and Myoviridae bacteriophages inhibits the growth of Pectobacterium spp. under in vitro and in vivo conditions. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duc, H.M.; Son, H.M.; Ngan, P.H.; Sato, J.; Masuda, Y.; Honjoh, K.I.; Miyamoto, T. Isolation and application of bacteriophages alone or in combination with nisin against planktonic and biofilm cells of Staphylococcus aureus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 5145–5158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.; Taha, O.; El-Sherif, H.M.; Connerton, P.L.; Hooton, S.P.T.; Bassim, N.D.; Connerton, I.F.; El-Shibiny, A. Bacteriophage ZCSE2 is a Potent Antimicrobial Against Salmonella enterica Serovars: Ultrastructure, Genomics and Efficacy. Viruses 2020, 12, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Ma, W.; Li, W.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. A broad-spectrum phage controls multidrug-resistant Salmonella in liquid eggs. Food Res. Int. 2020, 132, 109011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo-Calap, P.; Beamud, B.; Mora-Quilis, L.; González-Candelas, F.; Sanjuán, R. Isolation and Characterization of Two Klebsiella pneumoniae Phages Encoding Divergent Depolymerases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Zhao, F.; Sun, H.; Yu, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, W.; Pan, Q.; Ren, H. Characterization and Complete Genome Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bacteriophage vB_PaeP_LP14 Belonging to Genus Litunavirus. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 2465–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabiey, M.; Roy, S.R.; Holtappels, D.; Franceschetti, L.; Quilty, B.J.; Creeth, R.; Sundin, G.W.; Wagemans, J.; Lavigne, R.; Jackson, R.W. Phage biocontrol to combat Pseudomonas syringae pathogens causing disease in cherry. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 13, 1428–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spruit, C.M.; Wicklund, A.; Wan, X.; Skurnik, M.; Pajunen, M.I. Discovery of Three Toxic Proteins of Klebsiella Phage fHe-Kpn01. Viruses 2020, 12, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, S.Y.; Chen, L.K.; Wu, W.J.; Paramita, P.; Yang, P.W.; Li, Y.Z.; Lai, M.J.; Chang, K.C. Isolation and Characterization of a New Phage Infecting Elizabethkingia anophelis and Evaluation of Its Therapeutic Efficacy in vitro and in vivo. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Serrano, R.; Dunne, M.; Rosselli, R.; Martin-Cuadrado, A.B.; Grosboillot, V.; Zinsli, L.V.; Roda-Garcia, J.J.; Loessner, M.J.; Rodriguez-Valera, F. Alteromonas Myovirus V22 Represents a New Genus of Marine Bacteriophages Requiring a Tail Fiber Chaperone for Host Recognition. mSystems 2020, 5, e00217-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furfaro, L.L.; Payne, M.S.; Chang, B.J. Host range, morphological and genomic characterisation of bacteriophages with activity against clinical Streptococcus agalactiae isolates. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buttimer, C.; Lynch, C.; Hendrix, H.; Neve, H.; Noben, J.P.; Lavigne, R.; Coffey, A. Isolation and Characterization of Pectobacterium Phage vB_PatM_CB7: New Insights into the Genus Certrevirus. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, O.; Retamales, J.; Núñez, M.; León, M.; Salinas, P.; Besoain, X.; Yañez, C.; Bastías, R. Characterization of Bacteriophages against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae with Potential. Use as Natural Antimicrobials in Kiwifruit Plants. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, T.; Sun, H.; Pan, Q.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, H. Isolation and characterization of Vibrio parahaemolyticus bacteriophage vB_VpaS_PG07. Virus Res. 2020, 286, 198080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evseev, P.; Sykilinda, N.; Gorshkova, A.; Kurochkina, L.; Ziganshin, R.; Drucker, V.; Miroshnikov, K. Pseudomonas Phage PaBG-A Jumbo Member of an Old Parasite Family. Viruses 2020, 12, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filik, K.; Szermer-Olearnik, B.; Wernecki, M.; Happonen, L.J.; Pajunen, M.I.; Nawaz, A.; Qasim, M.S.; Jun, J.W.; Mattinen, L.; Skurnik, M.; et al. The Podovirus ϕ80-18 Targets the Pathogenic American Biotype 1B Strains of Yersinia enterocolitica. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, D.L.; McCutcheon, J.G.; Dennis, J.J. Characterization of Novel Broad-Host-Range Bacteriophage DLP3 Specific to Stenotrophomonas maltophilia as a Potential Therapeutic Agent. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambino, M.; Nørgaard Sørensen, A.; Ahern, S.; Smyrlis, G.; Gencay, Y.E.; Hendrix, H.; Neve, H.; Noben, J.P.; Lavigne, R.; Brøndsted, L. Phage S144, A New Polyvalent Phage Infecting Salmonella spp. and Cronobacter sakazakii. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelkader, K.; Gutiérrez, D.; Grimon, D.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Lood, C.; Lavigne, R.; Safaan, A.; Khairalla, A.S.; Gaber, Y.; Dishisha, T.; et al. Lysin LysMK34 of Acinetobacter baumannii Bacteriophage PMK34 Has a Turgor Pressure-Dependent Intrinsic Antibacterial Activity and Reverts Colistin Resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e01311–e01320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCutcheon, J.G.; Lin, A.; Dennis, J.J. Isolation and Characterization of the Novel Bacteriophage AXL3 against Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, T.L.; Song, Y.; Bryan, D.W.; Hudson, L.K.; Denes, T.G. Mutant and Recombinant Phages Selected from In Vitro Coevolution Conditions Overcome Phage-Resistant Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e02138-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujiki, J.; Furusawa, T.; Munby, M.; Kawaguchi, C.; Matsuda, Y.; Shiokura, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Nakamura, T.; Sasaki, M.; Usui, M.; et al. Susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa veterinary isolates to Pbunavirus PB1-like phages. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020, 64, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phothaworn, P.; Supokaivanich, R.; Lim, J.; Klumpp, J.; Imam, M.; Kutter, E.; Galyov, E.E.; Dunne, M.; Korbsrisate, S. Development of a broad-spectrum Salmonella phage cocktail containing Viunalike and Jerseylike viruses isolated from Thailand. Food Microbiol. 2020, 92, 103586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Tan, J.; Hao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yan, X.; Wang, D.; Tuo, L.; Wei, Z.; Huang, G. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Myophage Abp9 Against Pandrug Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 506068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Zhao, F.; Wang, J.; Pei, G.; Fan, H.; Zhangxiang, L.; Mi, Z.; Shi, T.; Liu, H.; Tong, Y. Biological characteristics and genome analysis of a novel phage vB_KpnP_IME279 infecting Klebsiella pneumoniae. Folia Microbiol. 2020, 65, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornienko, M.; Kuptsov, N.; Gorodnichev, R.; Bespiatykh, D.; Guliaev, A.; Letarova, M.; Kulikov, E.; Veselovsky, V.; Malakhova, M.; Letarov, A.; et al. Contribution of Podoviridae and Myoviridae bacteriophages to the effectiveness of anti-staphylococcal therapeutic cocktails. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Yuan, X.; Li, N.; Wang, J.; Yu, S.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Q.; Ding, Y. Isolation and Characterization of Bacillus cereus Phage vB_BceP-DLc1 Reveals the Largest Member of the Φ29-Like Phages. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skorynina, A.V.; Piligrimova, E.G.; Kazantseva, O.A.; Kulyabin, V.A.; Baicher, S.D.; Ryabova, N.A.; Shadrin, A.M. Bacillus-infecting bacteriophage Izhevsk harbors thermostable endolysin with broad range specificity. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosznik-Kwaśnicka, K.; Grabowski, Ł.; Grabski, M.; Kaszubski, M.; Górniak, M.; Jurczak-Kurek, A.; Węgrzyn, G.; Węgrzyn, A. Bacteriophages vB_Sen-TO17 and vB_Sen-E22, Newly Isolated Viruses from Chicken Feces, Specific for Several Salmonella enterica Strains. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova, A.V.; Shneider, M.M.; Arbatsky, N.P.; Kasimova, A.A.; Senchenkova, S.N.; Shashkov, A.S.; Dmitrenok, A.S.; Chizhov, A.O.; Mikhailova, Y.V.; Shagin, D.A.; et al. Specific Interaction of Novel Friunavirus Phages Encoding Tailspike Depolymerases with Corresponding Acinetobacter baumannii Capsular Types. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e01714-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korf, I.H.E.; Kittler, S.; Bierbrodt, A.; Mengden, R.; Rohde, C.; Rohde, M.; Kroj, A.; Lehnherr, T.; Fruth, A.; Flieger, A.; et al. In Vitro Evaluation of a Phage Cocktail Controlling Infections with Escherichia coli. Viruses 2020, 12, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, T.; Endo, H.; Ogata, H.; Chatchawankanphanich, O.; Yamada, T. The complete genomic sequence of the novel myovirus RP13 infecting Ralstonia solanacearum, the causative agent of bacterial wilt. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, W.; Sun, X. Characterization of vB_VpaP_MGD2, a newly isolated bacteriophage with biocontrol potential against multidrug-resistant Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zurabov, F.; Zhilenkov, E. Characterization of four virulent Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteriophages, and evaluation of their potential use in complex phage preparation. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertics, B.Z.; Szénásy, D.; Dunai, D.; Born, Y.; Fieseler, L.; Kovács, T.; Schneider, G. Isolation of a Novel Lytic Bacteriophage against a Nosocomial Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Belonging to ST45. Biomed. Res Int. 2020, 2020, 5463801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, H.J.; Giri, S.S.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, S.B.; Park, S.C. Bacteriophage as an alternative to prevent reptile-associated Salmonella transmission. Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, R.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; An, X.; Song, L.; Shi, T.; Fan, H.; Tong, Y.; et al. Biological characteristics and genomic analysis of a Stenotrophomonas maltophilia phage vB_SmaS_BUCT548. Virus Genes 2021, 57, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Cheng, X.; Li, J.; Yuan, X.; Huang, X.; Lian, M.; Li, W.; Huang, T.; Xie, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Novel Lytic Phages Protect Cells and Mice against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e01832-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Rio, B.; Sánchez-Llana, E.; Martínez, N.; Fernández, M.; Ladero, V.; Alvarez, M.A. Isolation and Characterization of Enterococcus faecalis-Infecting Bacteriophages From Different Cheese Types. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 592172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Leal, G.; Reyes-Muñoz, A.; Santamaria, R.I.; Cevallos, M.A.; Pérez-Monter, C.; Castillo-Ramírez, S. A novel vieuvirus from multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimamori, Y.; Pramono, A.K.; Kitao, T.; Suzuki, T.; Aizawa, S.I.; Kubori, T.; Nagai, H.; Takeda, S.; Ando, H. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Phage SaGU1 that Infects Staphylococcus aureus Clinical Isolates from Patients with Atopic Dermatitis. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 1267–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salem, M.; Pajunen, M.I.; Jun, J.W.; Skurnik, M. T4-like Bacteriophages Isolated from Pig Stools Infect Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia pestis Using LPS and OmpF as Receptors. Viruses 2021, 13, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, E.M.; Kelly, L.; Gannon, L.; Muscatt, G.; Dunstan, R.; Michniewski, S.; Sapkota, H.; Kiljunen, S.J.; Kolsi, A.; Skurnik, M.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of Klebsiella Phages for Phage Therapy. Phage 2021, 2, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.B.; Yu, M.S.; Tseng, T.T.; Lin, L.C. Molecular Characterization of Ahp2, a Lytic Bacteriophage of Aeromonas hydrophila. Viruses 2021, 13, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pertics, B.Z.; Cox, A.; Nyúl, A.; Szamek, N.; Kovács, T.; Schneider, G. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Lytic Bacteriophage against the K2 Capsule-Expressing Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae Strain 52145, and Identification of Its Functional Depolymerase. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.Y.; Thapa Magar, R.; Kim, H.J.; Choi, K.; Lee, S.W. Complete Genome Sequence of a Novel Bacteriophage RpY1 Infecting Ralstonia solanacearum Strains. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 2044–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.G.; Giri, S.S.; Yun, S.; Kim, S.W.; Han, S.J.; Kwon, J.; Oh, W.T.; Lee, S.B.; Park, Y.H.; Park, S.C. Two Novel Bacteriophages Control Multidrug- and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius Biofilm. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 524059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasurinen, J.; Spruit, C.M.; Wicklund, A.; Pajunen, M.I.; Skurnik, M. Screening of Bacteriophage Encoded Toxic Proteins with a Next Generation Sequencing-Based Assay. Viruses 2021, 13, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, T.; Leptihn, S.; Dong, K.; Loh, B.; Zhang, Y.; Stefan, M.I.; Li, M.; Guo, X.; Cui, Z. JD419, a Staphylococcus aureus Phage With a Unique Morphology and Broad Host Range. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 602902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fišarová, L.; Botka, T.; Du, X.; Mašlaňová, I.; Bárdy, P.; Pantůček, R.; Benešík, M.; Roudnický, P.; Winstel, V.; Larsen, J.; et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis Phages Transduce Antimicrobial Resistance Plasmids and Mobilize Chromosomal Islands. mSphere 2021, 6, e00223-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, P.; Hu, Y.; An, X.; Song, L.; Fan, H.; Tong, Y. Biochemical and genomic characterization of a novel bacteriophage BUCT555 lysing Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Virus Res. 2021, 301, 198465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nga, N.T.T.; Tran, T.N.; Holtappels, D.; Kim Ngan, N.L.; Hao, N.P.; Vallino, M.; Tien, D.T.K.; Khanh-Pham, N.H.; Lavigne, R.; Kamei, K.; et al. Phage Biocontrol of Bacterial Leaf Blight Disease on Welsh Onion Caused by Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. allii. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauppinen, A.; Siponen, S.; Pitkänen, T.; Holmfeldt, K.; Pursiainen, A.; Torvinen, E.; Miettinen, I.T. Phage Biocontrol of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Water. Viruses 2021, 13, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shchurova, A.S.; Shneider, M.M.; Arbatsky, N.P.; Shashkov, A.S.; Chizhov, A.O.; Skryabin, Y.P.; Mikhaylova, Y.V.; Sokolova, O.S.; Shelenkov, A.A.; Miroshnikov, K.A.; et al. Novel Acinetobacter baumannii Myovirus TaPaz Encoding Two Tailspike Depolymerases: Characterization and Host-Recognition Strategy. Viruses 2021, 13, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.; Park, Y.; Ryu, S. Development of new strategy combining heat treatment and phage cocktail for post-contamination prevention. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, B.; Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Ren, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C. Characterization of a Novel Bacteriophage swi2 Harboring Two Lysins Can Naturally Lyse Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 670799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Li, P.; Chen, L.; Guo, G.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, L.; Du, H.; Zhang, W. Identification of a phage-derived depolymerase specific for KL64 capsule of Klebsiella pneumoniae and its anti-biofilm effect. Virus Genes 2021, 57, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Zhou, B.; Zhu, W. Pathogenic Escherichia coli-Specific Bacteriophages and Polyvalent Bacteriophages in Piglet Guts with Increasing Coliphage Numbers after Weaning. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e0096621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.G.; Roh, E.; Park, J.; Giri, S.S.; Kwon, J.; Kim, S.W.; Kang, J.W.; Lee, S.B.; Jung, W.J.; Lee, Y.M.; et al. The Bacteriophage pEp_SNUABM_08 Is a Novel Singleton Siphovirus with High Host Specificity for Erwinia pyrifoliae. Viruses 2021, 13, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, H.Y.P.; Lai, M.J.; Chen, T.Y.; Wu, W.J.; Peng, S.Y.; Chang, K.C. Therapeutic Effect of a Newly Isolated Lytic Bacteriophage against Multi-Drug-Resistant Cutibacterium acnes Infection in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, A.; Dong, Z.; Liu, J.; Tahir, R.A.; Ashraf, N.; Qing, H.; Peng, D.; Tong, Y. Isolation, Characterization, and Genome Sequence Analysis of a Novel Lytic Phage, Xoo-sp15 Infecting Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 3192–3200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blundell-Hunter, G.; Enright, M.C.; Negus, D.; Dorman, M.J.; Beecham, G.E.; Pickard, D.J.; Wintachai, P.; Voravuthikunchai, S.P.; Thomson, N.R.; Taylor, P.W. Characterisation of Bacteriophage-Encoded Depolymerases Selective for Key Klebsiella pneumoniae Capsular Exopolysaccharides. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 686090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; Gao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Cheng, Y.; Ma, J.; Wang, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. Bacteriophage Cocktails Protect Dairy Cows Against Mastitis Caused By Drug Resistant Escherichia coli Infection. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 690377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.; Sun, Q.; Chen, H.; Wu, Q.; Chen, M.; Yang, S.; Du, M.; Zha, F.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, J. Isolation and Characterization of a Novel Salmonella Phage vB_SalP_TR2. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 664810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Tong, S.; Li, P.; An, X.; Song, L.; Fan, H.; Tong, Y. Characterization and genome sequence of the genetically unique Escherichia bacteriophage vB_EcoM_IME392. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 2505–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whittard, E.; Redfern, J.; Xia, G.; Millard, A.; Ragupathy, R.; Malic, S.; Enright, M.C. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Novel Polyvalent Bacteriophages With Potent In Vitro Activity Against an International Collection of Genetically Diverse Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 698909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, Y.T.; Salvador, A.; Lavenburg, V.M.; Wu, V.C.H. Characterization of Two New Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli O103-Infecting Phages Isolated from an Organic Farm. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonjan, S.; Cooper, C.J.; Nilsson, A.S. Complete Genome Sequence of vB_EcoP_SU7, a Podoviridae Coliphage with the Rare C3 Morphotype. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.W.; Park, J.H. Characterization and Food Application of the Novel Lytic Phage BECP10: Specifically Recognizes the O-polysaccharide of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Viruses 2021, 13, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, R.; Yu, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Liu, X. Molecular Characteristics of Novel Phage vB_ShiP-A7 Infecting Multidrug-Resistant Shigella flexneri and Escherichia coli, and Its Bactericidal Effect in vitro and in vivo. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 698962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dien, L.T.; Ky, L.B.; Huy, B.T.; Mursalim, M.F.; Kayansamruaj, P.; Senapin, S.; Rodkhum, C.; Dong, H.T. Characterization and protective effects of lytic bacteriophage pAh6.2TG against a pathogenic multidrug-resistant Aeromonas hydrophila in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, e435–e450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozdeveci, A.; Akpınar, R.; Karaoğlu, Ş.A. Isolation, characterization, and comparative genomic analysis of vB_PlaP_SV21, new bacteriophage of Paenibacillus larvae. Virus Res. 2021, 305, 198571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timoshina, O.Y.; Shneider, M.M.; Evseev, P.V.; Shchurova, A.S.; Shelenkov, A.A.; Mikhaylova, Y.V.; Sokolova, O.S.; Kasimova, A.A.; Arbatsky, N.P.; Dmitrenok, A.S.; et al. Novel Acinetobacter baumannii Bacteriophage Aristophanes Encoding Structural Polysaccharide Deacetylase. Viruses 2021, 13, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, A.A.; Addy, H.S.; Huang, Q. Biological and Molecular Characterization of a Jumbo Bacteriophage Infecting Plant Pathogenic Ralstonia solanacearum Species Complex Strains. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 741600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigvava, S.; Kusradze, I.; Tchgkonia, I.; Karumidze, N.; Dvalidze, T.; Goderdzishvili, M. Novel lytic bacteriophage vB_GEC_EfS_9 against Enterococcus faecium. Virus Res. 2022, 307, 198599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, G.; Holtappels, D.; Vallino, M.; Chiapello, M.; Turina, M.; Lavigne, R.; Wagemans, J.; Ciuffo, M. Molecular Characterization and Taxonomic Assignment of Three Phage Isolates from a Collection Infecting Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae and, P. syringae pv. phaseolicola from Northern Italy. Viruses 2021, 13, 2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerl, J.A.; Barac, A.; Erben, P.; Fuhrmann, J.; Gadicherla, A.; Kumsteller, F.; Lauckner, A.; Müller, F.; Hertwig, S. Properties of Two Broad Host Range Phages of Yersinia enterocolitica Isolated from Wild Animals. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.J.; Kim, M. Improved bactericidal efficacy and thermostability of Staphylococcus aureus-specific bacteriophage SA3821 by repeated sodium pyrophosphate challenges. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loose, M.; Sáez Moreno, D.; Mutti, M.; Hitzenhammer, E.; Visram, Z.; Dippel, D.; Schertler, S.; Tišáková, L.P.; Wittmann, J.; Corsini, L.; et al. Natural Bred ε2-Phages Have an Improved Host Range and Virulence against Uropathogenic Escherichia coli over Their Ancestor Phages. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Happonen, L.J.; Pajunen, M.I.; Jun, J.W.; Skurnik, M. BtuB-Dependent Infection of the T5-like Yersinia Phage ϕR2-01. Viruses 2021, 13, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Zeng, F.; Wu, Z.; Jin, Z.; Li, W.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Q.; Tong, Y.; Chen, L.; Bai, Q. Isolation and genomic analysis of temperate phage 5W targeting multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 204, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, N.; Mohan, B.; Mavuduru, R.S.; Kumar, Y.; Taneja, N. Characterization, genome analysis and in vitro activity of a novel phage vB_EcoA_RDN8.1 active against multi-drug resistant and extensively drug-resistant biofilm-forming uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates, India. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 3387–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, L.K.; Silva, E.C.; Rossi, F.P.; Cieza, B.; Oliveira, T.J.; Pereira, C.; Tomazetto, G.; Silva, B.B.; Squina, F.M.; Vila, M.M.; et al. Characterization and in vitro testing of newly isolated lytic bacteriophages for the biocontrol of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Future Microbiol. 2022, 17, 111–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerl, J.A.; Barac, A.; Bienert, A.; Demir, A.; Drüke, N.; Jäckel, C.; Matthies, N.; Jun, J.W.; Skurnik, M.; Ulrich, J.; et al. Birds Kept in the German Zoo “Tierpark Berlin” Are a Common Source for Polyvalent Yersinia pseudotuberculosis Phages. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 634289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runtuvuori-Salmela, A.; Kunttu, H.M.T.; Laanto, E.; Almeida, G.M.F.; Mäkelä, K.; Middelboe, M.; Sundberg, L.R. Prevalence of genetically similar Flavobacterium columnare phages across aquaculture environments reveals a strong potential for pathogen control. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 24, 2404–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacios, O.; Fernández-García, L.; Bleriot, I.; Blasco, L.; Ambroa, A.; López, M.; Ortiz-Cartagena, C.; Cuenca, F.F.; Oteo-Iglesias, J.; Pascual, Á.; et al. Phenotypic and Genomic Comparison of Klebsiella pneumoniae Lytic Phages: vB_KpnM-VAC66 and vB_KpnM-VAC13. Viruses 2021, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazantseva, O.A.; Buzikov, R.M.; Pilipchuk, T.A.; Valentovich, L.N.; Kazantsev, A.N.; Kalamiyets, E.I.; Shadrin, A.M. The Bacteriophage Pf-10-A Component of the Biopesticide “Multiphage” Used to Control Agricultural Crop Diseases Caused by Pseudomonas syringae. Viruses 2021, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera-Mansilla, J.; Sánchez, P.; Silva-Valenzuela, C.A.; Molina-Quiroz, R.C. Isolation and Characterization of Novel Lytic Phages Infecting Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0167821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Huang, Q.; Xie, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Y.; Chen, M.; Xue, L.; Wu, Q.; et al. Characterization of the Novel Phage vB_VpaP_FE11 and Its Potential Role in Controlling Vibrio parahaemolyticus Biofilms. Viruses 2022, 14, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, L.; Han, K.; Wang, L.; Cao, Y.; Ma, D.; Wang, X. A Polyvalent Broad-Spectrum Escherichia Phage Tequatrovirus EP01 Capable of Controlling Salmonella and Escherichia coli Contamination in Foods. Viruses 2022, 14, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Gómez, J.P.; López-Cuevas, O.; Castro-Del Campo, N.; González-López, I.; Martínez-Rodríguez, C.I.; Gomez-Gil, B.; Chaidez, C. Genomic and biological characterization of the novel phages vB_VpaP_AL-1 and vB_VpaS_AL-2 infecting Vibrio parahaemolyticus associated with acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND). Virus Res. 2022, 312, 198719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, Q.; Zong, Z. Lytic Phages against ST11 K47 Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and the Corresponding Phage Resistance Mechanisms. mSphere 2022, 7, e0008022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Yuan, X.; Li, C.; Chen, N.; Wang, J.; Chen, B.; Yu, S.; Yu, P.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, H.; et al. A novel Bacillus cereus bacteriophage DLn1 and its endolysin as biocontrol agents against Bacillus cereus in milk. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 369, 109615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, K.; He, X.; Fan, H.; Song, L.; An, X.; Li, M.; Tong, Y. Characterization and genome analysis of a novel Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteriophage BUCT598 with extreme pH resistance. Virus Res. 2022, 314, 198751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarakanov, R.I.; Lukianova, A.A.; Evseev, P.V.; Toshchakov, S.V.; Kulikov, E.E.; Ignatov, A.N.; Miroshnikov, K.A.; Dzhalilov, F.S. Bacteriophage Control of Pseudomonas savastanoi pv. glycinea in Soybean. Plants 2022, 11, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mencke, J.L.; He, Y.; Filippov, A.A.; Nikolich, M.P.; Belew, A.T.; Fouts, D.E.; McGann, P.T.; Swierczewski, B.E.; Getnet, D.; Ellison, D.W.; et al. Identification and Characterization of vB_PreP_EPr2, a Lytic Bacteriophage of Pan-Drug Resistant Providencia rettgeri. Viruses 2022, 14, 708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, H.; Lin, C.; Xu, Y.; Hu, M.; Xu, Z.; Geng, S.; Jiao, X.; Chen, X. A phage for the controlling of Salmonella in poultry and reducing biofilms. Vet. Microbiol. 2022, 269, 109432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmody, C.M.; Farquharson, E.L.; Nugen, S.R. Enterobacteria Phage SV76 Host Range and Genomic Characterization. Phage 2022, 3, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.; Guo, G.; Li, P.; Ma, J.; Chen, R.; Du, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W. Identification of a phage-derived depolymerase specific for KL47 capsule of Klebsiella pneumoniae and its therapeutic potential in mice. Virol. Sin. 2022, 37, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.M.; Ruest, M.K.; Cole, J.H.; Dennis, J.J. The Isolation and Characterization of a Broad Host Range Bcep22-like Podovirus JC1. Viruses 2022, 14, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, H.; Yang, H.; Yan, N.; Hou, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zhou, M. Bacteriostatic effects of phage F23s1 and its endolysin on Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Basic Microbiol. 2022, 62, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kim, B.; Song, S.; Lee, Y.W.; Roh, E. Isolation of Nine Bacteriophages Shown Effective against Erwinia amylovora in Korea. Plant Pathol. J. 2022, 38, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Hou, Y.; Huang, X.; Wang, S.; Xie, R.; Yang, J.; Lv, Q.; Hua, L.; Liang, W.; Peng, Z.; et al. Isolation of Three Coliphages and the Evaluation of Their Phage Cocktail for Biocontrol of Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli O157 in Milk. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Ma, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Han, K.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X. Isolation and characterization of a novel Escherichia coli phage Kayfunavirus ZH4. Virus Genes 2022, 58, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Wang, X.; Mou, Z.; Ren, H.; Zhang, C.; Zou, L.; Liu, H.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z. Characterization and genome analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage vB_PaeP_Lx18 and the antibacterial activity of its lysozyme. Arch. Virol. 2022, 167, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCutcheon, J.G.; Lin, A.; Dennis, J.J. Characterization of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia phage AXL1 as a member of the genus Pamexvirus encoding resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]