Abstract

Sever fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) is a new infectious disease that has emerged in recent years and is widely distributed, highly contagious, and lethal, with a mortality rate of up to 30%, especially in people with immune system deficiencies and elderly patients. SFTS is an insidious, negative-stranded RNA virus that has a major public health impact worldwide. The development of a vaccine and the hunt for potent therapeutic drugs are crucial to the prevention and treatment of Bunyavirus infection because there is no particular treatment for SFTS. In this respect, investigating the mechanics of SFTS–host cell interactions is crucial for creating antiviral medications. In the present paper, we summarized the mechanism of interaction between SFTS and pattern recognition receptors, endogenous antiviral factors, inflammatory factors, and immune cells. Furthermore, we summarized the current therapeutic drugs used for SFTS treatment, aiming to provide a theoretical basis for the development of targets and drugs against SFTS.

1. Introduction

In 2009, The National Center for Disease Control and Prevention of China received test samples from a patient in Hubei Province, China, who had identical signs to a patient from Hubei province with symptoms of fever, malaise, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia. The Chinese Center for Health CDC then isolated a novel virus from this patient, and it was later identified as SFTSV1 after being found in all 81 identical patients who presented in the ensuing months [1]. Since then, reports of the virus’s emergence have come from Japan [2], South Korea [3], Pakistan [4], Vietnam [5], and many other nations and areas. One of the primary vectors for this virus is ticks, and infected ticks that attach to humans and draw blood from them release and transmit SFTSV as a result of this blood-sucking process [6,7]. As a result, people who have had high levels of interaction with ticks are more likely to develop fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Additionally, recent research indicates that cats are extremely susceptible to SFTSV, so it is important to take into account the possibility of human infection in cats with SFTS [8]. The incubation period following SFTSV infection is typically 5 to 14 days. Fever, gastrointestinal discomfort, and thrombocytopenia, and in extreme instances, pancreatic injury, myocardial injury, and even central nervous system lesions and encephalitis, are common clinical manifestations [1,9,10]. In this overview, the virology of the virus, interactions between the virus and its hosts, and antiviral drug research are all summarized and discussed.

Bunyaviruses are the largest known family of RNA viruses, and more than 350 viruses have been identified, classified according to serological, morphological, and biochemical characteristics into the genera Orthobunyavirus, Nairovirus, Phlebovirus, Hantavirus, and Tospovirus, as well as other unclassified viruses [11]. In 2011, Yu et al. identified SFTSV as a spherical, enveloped, and segmented negative-stranded RNA virus belonging to the genus Phlebovirus Bunyavirus by whole genome determination of 12 SFTSV strains isolated from Chinese SFTS patients. The genome of this viral genus consists of a group of segmented single-stranded negative-sense RNA motifs encoding small (S), medium (M), and large (L) segments [1], which are structurally similar to those of other bunyaviruses [12].

SFTSV is highly similar in genetic structure to Heartland virus and Guertu virus of the same genus [13,14]. The HV virus was isolated and discovered in Missouri, USA, in 2012, which also belongs to the genus Phlebovirus [15], and Guertu virus was discovered in 2014 from Xinjiang province, China [14]. Encoding viral nucleocapsid proteins (NPs) and nonstructural proteins (NSs) were identified on the S fragment of SFTSV, the most abundant protein in SFTSV particles and infected cells, which wraps the RNA (vRNA) of the viral genome and leads to the formation of ribonucleoprotein complexes (RNPs). NPs play a protective role in viral replication and assembly and are responsible for encapsulating and protecting viral genomic RNA from degradation by exogenous nucleases and the innate immune system in the host cell [16]; NSs are also important virulence protein factors of SFTSV and are strong inhibitors of IFN production, which inhibit the natural antiviral response of the host cell in several ways [17].

It has also been demonstrated that NS proteins can form viral plasma-like structures (VLSs) in infected and transfected cells, and viral dsRNA is localized in the VLS of infected cells, suggesting that VLSs formed by NSs may be associated with SFTS bunyavirus replication [18]. Numerous studies have reported that NSs and NPs inhibit host cell antiviral immune responses by suppressing interferon and cytosolic nuclear factor signaling, and lead to multi-organ dysfunction. In addition, the S segment encodes a nuclear protein of SFTSV, which inhibits the activation of IFN-β and NF-κB signaling pathways [19]. Besides, the M segment encodes a nuclear protein precursor (Gp), which is cleaved and modified by proteases during translation to yield structural glycoprotein N (Gn), glycoprotein C (Gc) monomers, and Gn/Gc proteins, which mediate viral entry into host cells via pH-dependent endocytosis, while Gn promotes early SFTSV infection, interacts with host cell receptors, and serves as a major target for neutralizing immune responses. The L fragment specifies the viral gene’s RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), which is responsible for viral RNA replication and mRNA synthesis [20].

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the L segment is capable of initiating viral RNA replication and mRNA synthesis without the use of primers or reassignment. The L segment most likely starts genome replication on vRNA without the use of primer and reassignment mechanisms [21]. Recombination and partial reassignment on SFTSV S, M, and L sequences may also enable the virus to evolve and evade the host immune response. Venous viral serocomplexes are a class of serum cross-reactive viruses that are phylogenetically related to and transmitted by arthropod vectors. This group of viruses can also be spread by mosquitos (e.g., Rift Valley fever virus; RVFV) or sand flies, in addition to ticks (e.g., Tuscany virus).

2. Viral Evasion of Immunization Modes

SFTSV entry into the host cell is initiated by recruitment of lattice proteins to the cell membrane to form lattice-protein-coated pits and further extrusion from the plasma membrane to form discrete vesicles. These vesicle carriers further deliver viral particles to Rab5+ early endonucleosomes and then to Rab7+ late endonucleosomes. Intracellular transport of endocytic vesicles carrying viral particles is dependent first on actin filaments at the cell periphery and then on microtubules inside the cell. The final fusion event occurs approximately 15–60 min after entry and is triggered by an acidic environment of ≈pH 5.6 within the late nucleosome. In addition, SFTSV entry into target cells requires Gn/Gc binding to cellular receptors and fusion of the virus with the cell membrane, a process catalyzed by conformational changes in viral proteins and subsequent release of viral RNA into the cytoplasm [22].

3. Innate Immunity

The innate immune response is the first line of defense against SFTSV infection; moreover, the ability of the host to suppress viral infection relies heavily on the effectiveness of the initial antiviral innate immune response, and activation of innate immune cells is critical to initiate adaptive immunity. Innate immune cells use pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and danger-associated molecular patterns (dAMPs) to detect viruses [23]. Upon entry into the body, SFTSV dsRNA is recognized and signaled to the next junction by pattern recognition receptors such as RIG-like receptors and Toll-like receptors.

IFN: Interferons are powerful antiviral cytokines that induce various antiviral responses to inhibit viral replication. Interferons are divided into three types (type I, type II, and type III) based on sequence homology, with type I and type III IFNs being more important. Type I interferons are further divided into thirteen subtypes including IFN-α and IFN-β, and type III IFNs are divided into IFN-λ1, IFN-λ2, and IFN-λ3 [24]. In the recognition process of SFTSV-infected cells, RIG-I is the main recognition receptor for the viral RNA sensor molecule, which makes the IFN-β promoter stimulator 1 (IPS-1) or the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein MAVS. IPS-1 signals to TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and NF-κB kinase inhibitor (IKK) to induce type I IFN secretion by activating the phosphorylation of IFN regulators IRF3 and IRF7 [25].

TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1): TBK1 (tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor-associated factor NF-κB activator (TANK)-binding kinase 1), is involved in the activation of multiple cellular pathways leading to the production of IFN and proinflammatory cytokines after infection, autophagic degradation of protein aggregates or pathogens, and homeostatic cellular functions such as cell growth and proliferation [26]. During SFTSV invasion of host cells, the interaction of NSs with TBK1 is an important pathway for inhibition of host interferon, and NSs bind to TBK1 to isolate it into NS-induced cytoplasmic structures, a critical step in SFSTV evasion of host antiviral responses. SFTSV NSs associate with TBK1 through its N-terminal kinase structural domain, thereby blocking the autophosphorylation of TBK1, which ultimately inhibits IFN production [27]. Moreover, in a report, it was demonstrated that SFTSV can inhibit the induction of IFN-a and IFN-b through NS–IRF7 interactions and the isolation of IRF7 in the viral envelope [28].

STAT2 (signal transducer and activator of transcription) is an important factor in IFN production. Phosphorylated homodimers or heterodimers of STAT2 together with IRF9 form the ISGF3 complex, which translocates into the nucleus, binds to specific IFN stimulatory responses in the promoters of IFN-stimulated gene (ISG) elements (ISREs) in the promoter of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), and activates ISGs’ transcription [29]. During the IFN signaling phase, SFTSV NS proteins inhibit IFN signaling and ISGs’ expression by segregating STAT2 into inclusion bodies (IBs) and impairing STAT2 heterodimer phosphorylation and nuclear translocation [30]. Furthermore, in a study, Xu Chen et al. first found that SFTSV inhibits exogenous IFN α-induced Jak/STAT signaling by reducing Y701 p-STAT1 levels, inhibiting IFN stimulatory response element ISRE activity, and downregulating ISGs’ expression [31]. Both studies suggest that SFTSV NS proteins can inhibit exogenous IFN α-induced Jak/STAT signaling by suppressing STAT1 phosphorylation and activation, and that SFTSV inhibits Jak/STAT signaling to inhibit type I and type III IFN signaling. In addition to this, in an in vivo experiment in mouse animals, SFTSV was found to induce fatal acute disease in STAT2-deficient mice, but not in STAT1-deficient mice. This is due to the inability of NSs to bind to mouse STAT2 and inhibit type I IFN signaling in mouse cells. This implies that dysfunction of NSs in antagonizing mouse STAT2 can lead to inefficient replication and loss of pathogenesis of SFTSV in mice [32]. This was likewise argued in another animal experimental model, where Gowen et al. demonstrated that hamsters lacking functional STAT2 were highly sensitive to SFTSV down to 10 PFU and that animals usually died within 5 to 6 days after subcutaneous stimulation [33].

TRIM21 and TRIM25. Most of the TRIM family proteins have E3 ubiquitin ligase activity and play multiple functions in intracellular signaling, development, apoptosis, protein amount control, innate immunity, autophagy, and carcinogenesis. There is growing evidence that TRIM family proteins have unique and important roles, and their dysregulation leads to several diseases such as cancer, immune disorders, or developmental disorders [34]. TRIM21 mediates monoubiquitination and subcellular translocation of active IKKB to autophagosomes and inhibits IKKB-mediated NF-κB signaling [35]. Choi, Y. et al. demonstrated that the SFTSV NSs inhibits the TRIM21 function to upregulate the p62-Keap1-Nrf2 antioxidant pathway for efficient viral pathogenesis [36]. Besides, TRIM25-mediated k63-linked ubiquitination of retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I), which induces RIG-I-mediated IFN production [37], revealed that SFTSV NSs can specifically capture TRIM25 into viral inclusion bodies and inhibit TRIM25-mediated ubiquitination/activation of the RIG-Lys-63 linkage, contributing to the inhibition of RLR-mediated antiviral signaling during its initial phase [38].

IRF family. Interferon regulatory factors (IRFs) are a family of homologous proteins responsible for the regulation of IFN transcription and IFN-induced gene expression. They are important regulatory proteins in the Toll-like receptor (TLR) and IFN signaling pathways, which are essential elements of the innate immune system [39]. Studies have demonstrated that, during SFTSV invasion of host cells, its NSs chelate TBK1 into the cytoplasmic structure induced by NSs, indirectly inhibiting IRF3 and subsequent IFN-β production. It has also been demonstrated that NSs with 21 and 2 conserved amino acids at position 23 are essential for the inhibition of IRF3 phosphorylation and IFN-β mRNA expression [40]. Ye Hong et al. demonstrated that NSs directly interact with IRF7 and chelate it into the inclusion bodies, unlike IRF3, which indirectly interacts with NSs. Although the interaction of NSs with IRF7 did not inhibit IRF7 phosphorylation, p-IRF7 was trapped in the inclusion bodies, leading to a significant reduction in IFN-2, IFN4 induction, and thus enhanced viral replication [28]. In addition, LSm14A, a member of the LSm family, is involved in RNA processing in the processing body, binds to viral RNA or synthetic homologs, and mediates IRF3 activation and IFN-β induction, and it has been shown that the cellular NS proteins interact and co-localize with LSm14A, and this interaction effectively inhibits downstream phosphorylation and dimerization of IRF3, thereby inhibiting antiviral signaling pathways and IFN induction in several human cell types. The SFTSV NS LRRD motif binds to the LSm14A–NS protein complex, thereby affecting IFN release [41]. The interaction of viral NSs with IRF7 and IRF3 and the subsequent immobilization of these transcription factors into the viral envelope is a unique strategy used by this vein virus to ensure effective evasion and suppression of host innate immunity.

NF-κB: NF-κB, an important transcription factor, has various biological functions during viral infection, such as pro-inflammatory, antiviral, and apoptotic responses. It was found that TBK1 inhibits the NF-κB signaling pathway and cytokine/chemokine induction in a kinase-activity-dependent manner and that NSs of SFTSV isolate TBK1 to prevent its inhibition of NF-κB, thereby promoting the activation of NF-κB and its target cytokine/chemokine genes [42]. another study discovered that SFTSV infection led to signifcant increases in proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines regulated by NF-κB signaling in liver epithelial cells, and the activation of NFκB signaling during infection promoted viral replication in liver epithelial cells [43].

Inflammatory factors. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is one of the powerful inflammatory factors, and the maturation and secretion of IL-1β is mediated by the nucleotide and oligomeric structural domain, leucine-rich repeat protein family, and nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) [44]. In macrophages, BCL2 antagonist 1 (BAX) and BAK/BCL2-related X (BAK) activation leads to the degradation of inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) protein, which promotes caspase-8-mediated activation of IL-1β. Notably, upon BAX/BAK activation, the apoptosis enforcers caspase-3 and caspase-7 act upstream of caspase-8 and NLRP3-induced IL-1β maturation and secretion. This demonstrates the ability of innate immune cells with BAX/BAK-mediated apoptosis to generate pro-inflammatory signals [45]. In addition, Li et al. found that SFTSV infection triggers BAK upregulation and BAX activation, leading to mitochondrial DNA oxidation and subsequent cytosol release and triggering NLRP3 inflammatory vesicle activation [46]. This was also demonstrated in the study of Gao et al. The N-terminal fragments of NSs, i.e., amino acids 1 to 66, promote inflammasome complex assembly by interacting with NLRP3 [47]. Excessive NLRP3 activation leads to IL-1β secretion and ultimately to severe fever in the body. In one paper, it was reported that viral load was positively correlated with the inflammatory factors IL-6 and IP-10 and negatively correlated with RANTES in 100 SFTS patients. This is because SFTSV can cause cytokine changes; that is, there are different degrees of fluctuations in cytokine levels in patients after the onset of the disease. IL-6 and IL-8 levels in the asymptomatic infection group differed significantly between the SFTS patient group and the healthy human group [48]. This was also demonstrated in an experiment with mouse hepatocytes, where infection of hepatic epithelial cells resulted in significant increases in pro-inflammatory and chemokines such as IL-6, RANTES, IP-10, and MIP-3a [43].

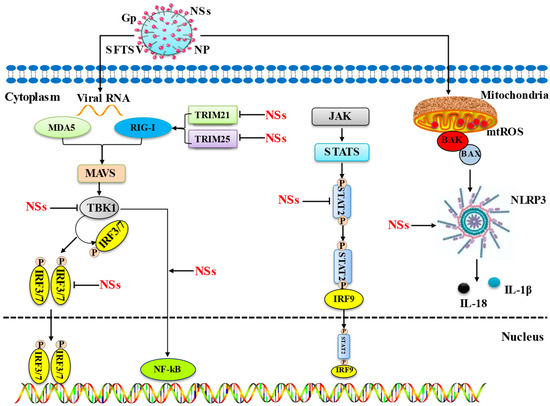

The mechanisms by which SFTS inhibits key immune signaling pathways and promotes inflammation are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mechanisms by which SFTS inhibits key immune signalling pathways and promotes inflammation. This diagram illustrates the main mechanism by which the host cell pathway is impacted by the NS proteins of SFTSV. Interferon release, the primary signaling mechanism for immune evasion, is inhibited by NSs in a number of ways, including the following: (1) NSs inhibit IFN production by isolating TRIM21/25, TBK1, STAT1/2, and IRF3/7 into their inclusion bodies. (2) Inhibition of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, thereby inhibiting IFN production. The toxic NS proteins of SFTS induce inflammation through two pathways, including the following: (1) NSs produce inflammatory factors by promoting the transcription of NF-kB into the nucleus. (2) NSs trigger BAK upregulation and BAX activation through infection, leading to mitochondrial DNA oxidation and subsequent cytosol release and triggering NLRP3 inflammasome activation, which leads to inflammatory factor production.

Autophagy and viral replication. After infection with SFTSV, cells stop at the G2/M transition, and the accumulation of cells at the G2/M transition does not affect viral adsorption and entry, but this does promote viral replication The interaction between viral NSs and CDK1 inhibits the formation of the cell cycle protein B1–CDK1 complex and nuclear import, leading to cell cycle arrest, and the expressed CDK1 loss-of-function mutants reverse the inhibitory effect of NSs on the cell cycle, thereby promoting viral replication [49]. In addition, it has been shown that SFTSV triggers a classical RB1CC1/FIP200-BECN1-ATG5-dependent autophagic flux and that the nuclear protein of SFTSV induces BECN1-dependent autophagy by disrupting the BECN1–BCL2 association. Importantly, SFTSV uses autophagy for the viral life cycle, which not only assembles in autophagosomes derived from the ERGIC and Golgi complexes, but also uses autophagic vesicles for extravasation [50].

The nuclear matrix protein nuclear scaffold attachment factor A (SAFA). Also known as heterogeneous ribonucleoprotein U, SAFA was recently identified as a novel nuclear RNA sensor that, upon recognition of viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), oligomerizes in the nucleus and functions as a super enhancer to promote activation of antiviral responses through interaction with chromatin remodeling complexes. SAFA recruits and promotes activation of the STING–TBK1 signaling axis against SFTSV infection, and SAFA functions as a novel cytoplasmic RNA sensor [51].

Arginine metabolic pathways. Through metabolomic analysis of two independent cohorts of SFTS patients, Li et al. found arginine deficiency in SFTS cases, suggesting that arginine metabolism by nitric oxide synthase and arginase is a key pathway for SFTSV infection and consequent death [52]. Moreover, arginine deficiency is associated with reduced intraplatelet nitric oxide (Plt-NO) concentrations, platelet activation, and thrombocytopenia.

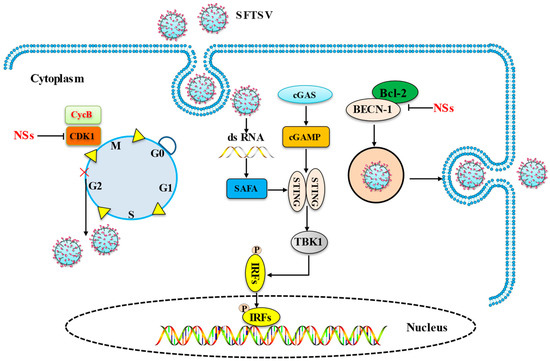

The SFTSV mediation of cell cycle, apoptosis, and the cGAS-STING pathway to achieve immune escape is summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

SFTSV mediates cell cycle, apoptosis, and the cGAS-STING pathway to achieve immune escape. The main mechanism by which the SFTSV influences the host cell pathway is depicted in this picture. (1) NSs inhibit host cell cycle protein CDK1 to achieve viral replication. (2) SAFA recruits and promotes activation of the STING–TBK1 signaling axis against SFTSV infection; (3) NSs induce BECN-1-dependent autophagy by breaking the BECN1–BCL2 linkage and complete virus replication.

4. Adapt Immunity

T cells: T lymphocytes are the primary immune cells that mediate cellular immune responses. Defective serologic responses to SFTSV have been found to correlate with disease morbidity and mortality, and T-cell damage leads to the disruption of antiviral immunity. Amplified and impaired antibody secretion is a hallmark of fatal SFTSV infection. Monocyte apoptosis early in infection reduces antigen presentation by dendritic cells, impedes T follicular helper cell differentiation and function, and leads to the failure of virus-specific humoral responses [53]. Yi et al. studied the dynamics of circulating regulatory T cells (Tregs) in SFTS patients at different stages. The results showed that the ratio of CD4+/total lymphocytes and CD4+CD25+/CD4+cells was significantly higher in the non-severe group than in the severe group. In contrast, the proportion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+/CD4+CD25+ cells was lower in the non-severe disease group than in the severe disease group. Furthermore, during the recovery period from SFTSV infection, circulating Tregs returned to the normal range. Tregs levels correlated with various clinical parameters, which demonstrated that SFTSV infection leads to a strong response of circulating Treg in SFTS patients [54].

B cells: B cell immune responses are regulated by antigen-presenting cells and Tfhs. It has been found that, during fatal infection, SFTSV leads to an excessive inflammatory response by significantly inducing abnormal inactivation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines as well as adaptive immune responses. Furthermore, the majority of SFTSV in fatal infections is found in plasma B cells. Thus, SFTSV infection inhibits the maturation and secretion of high-affinity antibodies in plasma B cells and suppresses the production of neutralizing antibodies, leading to significant viral replication and subsequent death [55]. In addition, a defective serologic response to SFTSV has been found to correlate with disease morbidity and mortality, with a combination of B and T cell damage leading to the destruction of antiviral immunity. The serology of deceased patients was characterized by a lack of specific IgG against the viral nucleocapsid (NP) and glycoprotein (Gn) owing to the failure of B-cell class switching [56]. In addition, Suzuki et al. found that B cells that differentiate into plasma cells and macrophages in secondary lymphoid organs are the end-stage SFTSV infection targets of SFTSV infection and that the majority of SFTSV-infected cells were B cell lineage lymphocytes. In infected individuals, SFTSV-infected B cell lineage lymphocytes are widely distributed in lymphoid and non-lymphoid organs, and the human plasmacytoid lymphoma cell line PBL-1 is susceptible to SFTSV transmission and has an immunophenotype similar to that of SFTSV lethal SFTS target cells [56].

Macrophages: miR-146a and miR-146b were significantly upregulated in macrophages during SFTSV infection, driving macrophage differentiation to M2 cells by targeting STAT1. Further analysis showed that elevated miR-146b, but not miR-146a, acted on IL-10 stimulation. In addition, SFTSV increased macrophage differentiation toward M2 cells mediated by viral nonstructural proteins (NSs) induced by endogenous miR-146b. Macrophage differentiation toward M2 bias may be important for the pathogenesis of SFTS [57].

Natural killer (NK) cells: NK cells are effector cells of the innate immune system that specialize in recognizing and destroying virally infected cells during the early stages of infection. NK cells in human peripheral blood can be divided into the following five NK subsets based on the relative expression of the markers CD16 (or FcγRIIIA, the low-affinity receptor for the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G) and CD56 (an adhesion molecule that mediates isotype adhesion): CD56brightCD16−, CD56brihtCD16+, CD56dimCD16−, CD56dimCD16+, and CD56−CD16+ [58]. Studies have shown that CD56dimCD16+ NK cells are associated with increased severity of SFTS, with higher levels of Ki-67 and granzyme B expression in CD56dimCD16+ and lower expression levels of NKG2A. Increased effector function of NK cells as well as CD56dim NK cells was observed in the acute phase of SFTS patients [59].

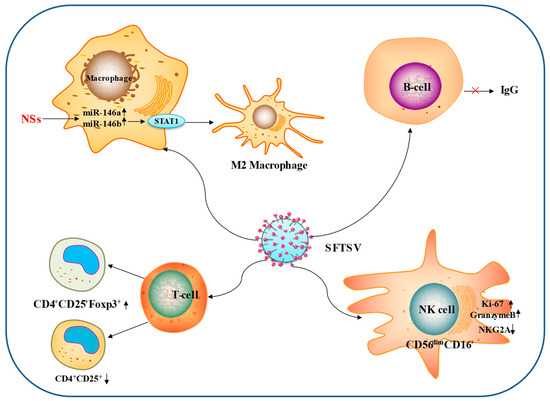

The interactions between SFTSV and immune cells are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Interactions between SFTSV and immune cells. The main ways in which SFTSV influences the immune cells through adaptive immunity are depicted in this diagram. (1) SFTSV increased the differentiation of macrophages into M2 cells NS-mediated endogenous miR-146b. (2) SFTSV increased the expression of Ki-67 and granzyme B in CD56dimCD16+ NK cells. (3) SFTSV inhibits IgG antibody production by B cells. (4) SFTSV promotes CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cell production and suppresses CD4+CD25+ T cells.

6. Chinese Medicinal Ingredients against SFTSV Virus

Li, S. et al. [95] obtained three compounds, Notoginsenoside Ft1, Punicalin, and Tosendanin, with high anti-SFTSV activity through high-throughput screening of a library of natural extracts of compounds with anti-SFTSV infection activity. Among them, Tosendanin showed the highest inhibitory capacity. Tosendanin is a type I voltage-dependent calcium channel agonist, which may be involved in the regulation of intracellular calcium homeostasis. Mechanistic studies have shown that Tosendanin can inhibit SFTSV infection during the internalization phase [95]. The antiviral effect of Tosendanin on SFTSV was further demonstrated in a mouse infection model, where Tosendanin treatment resulted in a significant reduction in viral load and histopathological changes in mice. The study also revealed that the antiviral activity of Tosendanin could be further extended to another bunyavirus and the emerging SARS-CoV-2. This will facilitate the discovery and development of anti-bunyavirus drugs.

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

In the decades since the discovery of SFTSV in China, a great deal of research has been collected on viral vectors, virology, and the way the virus invades the organism, as well as on drugs that target the virus. However, a considerable number of questions remain to be answered, such as the existence of SFTSV transmission from other mammals to humans, the transmission cycle of SFTSV, the complex immune response to the host, and so on. SFTSV causes mortality mainly by causing leukocytopenia and multi-organ failure and by causing severe fever in the body, leading to immune system failure, yet no effective treatment has been established. The non-structural domain NS proteins of SFTSV act as its main virulence protein and, by inhibiting host cell IFN synthesis and producing a large number of inflammatory factors, SFTSV disables the host cell immune system. It is likely that SFTSV has been circulating in China and the world for a considerable period of time, but has not been detected during this time, and it is likely that more strains of the virus will evolve over time. More information on the virus will certainly be gathered in the coming years, but the full extent of the human disease risk posed by SFTSV has not yet been fully determined. The death rate from SFTS is gradually decreasing as global medical care improves, but there is no fully effective vaccine or drug that can cure it, so an effective vaccine or drug has yet to be developed. Scholars and clinicians should actively share their experiences and continue to improve the information and treatment of the virus in order to combat the disease.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 82260723) and the Science and Technology Support Program of Guizhou province (NO. [2021]Genaral410).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yu, X.J.; Liang, M.F.; Zhang, S.Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.D.; Sun, Y.L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.F.; Popov, V.L.; Li, C.; et al. Fever with Thrombocytopenia Associated with a Novel Bunyavirus in China. N. Eng. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, C.; Shinohara, N.; Furuta, R.A.; Tanishige, N.; Shimojima, M.; Matsubayashi, K.; Nagai, T.; Tsubaki, K.; Satake, M. Investigation of antibody to severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) in blood samples donated in a SFTS-endemic area in Japan. Vox Sang. 2018, 113, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.R.; Yun, Y.; Bae, S.G.; Park, D.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.M.; Cho, N.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, K.H. Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus Infection, South Korea, 2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 2103–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zohaib, A.; Zhang, J.; Saqib, M.; Athar, M.A.; Hussain, M.H.; Chen, J.; Sial, A.U.; Tayyab, M.H.; Batool, M.; Khan, S.; et al. Serologic Evidence of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus and Related Viruses in Pakistan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1513–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, X.C.; Yun, Y.; Van An, L.; Kim, S.H.; Thao, N.T.P.; Man, P.K.C.; Yoo, J.R.; Heo, S.T.; Cho, N.H.; Lee, K.H. Endemic Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome, Vietnam. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.L.; Wang, X.J.; Li, J.D.; Ding, S.J.; Zhang, Q.F.; Qu, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, C.; Wu, W.; Jiang, M.; et al. Isolation, identification and characterization of SFTS bunyavirus from ticks collected on the surface of domestic animals. Bing Xue Bao Chin. J. Virol. 2012, 28, 252–257. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, L.; Sun, Y.; Cui, X.M.; Tang, F.; Hu, J.G.; Wang, L.Y.; Cui, N.; Yang, Z.D.; Huang, D.D.; Zhang, X.A.; et al. Transmission of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus by Haemaphysalis longicornis Ticks, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.S.; Shimojima, M.; Nagata, N.; Ami, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Iwata-Yoshikawa, N.; Fukushi, S.; Watanabe, S.; Kurosu, T.; Kataoka, M.; et al. Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Phlebovirus causes lethal viral hemorrhagic fever in cats. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, Z.T.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, M.F.; Jin, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, C.B.; Li, C.; Li, X.Y.; Zhang, Q.F.; Bian, P.F.; et al. Clinical progress and risk factors for death in severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome patients. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 206, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, N.; Liu, R.; Lu, Q.B.; Wang, L.Y.; Qin, S.L.; Yang, Z.D.; Zhuang, L.; Liu, K.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.A.; et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome bunyavirus-related human encephalitis. J. Infect. 2015, 70, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefkowitz, E.J.; Dempsey, D.M.; Hendrickson, R.C.; Orton, R.J.; Siddell, S.G.; Smith, D.B. Virus taxonomy: The database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D708–D717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, C.T.; Barr, J.N. Recent advances in the molecular and cellular biology of bunyaviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2011, 92 Pt 11, 2467–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brault, A.C.; Savage, H.M.; Duggal, N.K.; Eisen, R.J.; Staples, J.E. Heartland Virus Epidemiology, Vector Association, and Disease Potential. Viruses 2018, 10, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.Q.; Shi, C.; Yao, T.; Feng, K.; Mo, Q.; Deng, F.; Wang, H.; Ning, Y.J. The Nonstructural Protein of Guertu Virus Disrupts Host Defenses by Blocking Antiviral Interferon Induction and Action. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 857–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullan, L.K.; Folk, S.M.; Kelly, A.J.; MacNeil, A.; Goldsmith, C.S.; Metcalfe, M.G.; Batten, B.C.; Albariño, C.G.; Zaki, S.R.; Rollin, P.E.; et al. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N. Eng. J. Med. 2012, 367, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Ouyang, S.; Liang, M.; Niu, F.; Shaw, N.; Wu, W.; Ding, W.; Jin, C.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Structure of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus nucleocapsid protein in complex with suramin reveals therapeutic potential. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 6829–6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, J.; Kato, H.; Fujita, T. The Role of Non-Structural Protein NSs in the Pathogenesis of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome. Viruses 2021, 13, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Qi, X.; Liang, M.; Li, C.; Cardona, C.J.; Li, D.; Xing, Z. Roles of viroplasm-like structures formed by nonstructural protein NSs in infection with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. FASEB J. Off. Publ. Fed. Am. Soc. Exp. Biol. 2014, 28, 2504–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, B.; Qi, X.; Wu, X.; Liang, M.; Li, C.; Cardona, C.J.; Xu, W.; Tang, F.; Li, Z.; Wu, B.; et al. Suppression of the interferon and NF-κB responses by severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 8388–8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera, J.; Weber, F.; Cusack, S. Bunyaviridae RNA polymerases (L-protein) have an N-terminal, influenza-like endonuclease domain, essential for viral cap-dependent transcription. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, D.; Thorkelsson, S.R.; Quemin, E.R.J.; Meier, K.; Kouba, T.; Gogrefe, N.; Busch, C.; Reindl, S.; Günther, S.; Cusack, S.; et al. Structural and functional characterization of the severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus L protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 5749–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Tang, B.; Hu, L.; Deng, F.; Wang, H.; Pang, D.W.; Hu, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Y. Single-Particle Tracking Reveals the Sequential Entry Process of the Bunyavirus Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus. Small 2019, 15, e1803788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carty, M.; Guy, C.; Bowie, A.G. Detection of Viral Infections by Innate Immunity. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2021, 183, 114316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazear, H.M.; Schoggins, J.W.; Diamond, M.S. Shared and Distinct Functions of Type I and Type III Interferons. Immunity 2019, 50, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Shimojima, M.; Narita, R.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Kato, H.; Saijo, M.; Fujita, T. RIG-I-Like Receptor and Toll-Like Receptor Signaling Pathways Cause Aberrant Production of Inflammatory Cytokines/Chemokines in a Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus Infection Mouse Model. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e02246-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilli, M.; Arko-Mensah, J.; Ponpuak, M.; Roberts, E.; Master, S.; Mandell, M.A.; Dupont, N.; Ornatowski, W.; Jiang, S.; Bradfute, S.B.; et al. TBK-1 promotes autophagy-mediated antimicrobial defense by controlling autophagosome maturation. Immunity 2012, 37, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.K.; Shin, O.S. Nonstructural Protein of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Phlebovirus Inhibits TBK1 to Evade Interferon-Mediated Response. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 31, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Bai, M.; Qi, X.; Li, C.; Liang, M.; Li, D.; Cardona, C.J.; Xing, Z. Suppression of the IFN-α and -β Induction through Sequestering IRF7 into Viral Inclusion Bodies by Nonstructural Protein NSs in Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Bunyavirus Infection. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 841–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.M.; Chevillotte, M.D.; Rice, C.M. Interferon-stimulated genes: A complex web of host defenses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 513–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, Y.; Sakai, M.; Shimojima, M.; Saijo, M.; Itoh, M.; Gotoh, B. Nonstructural protein of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome phlebovirus targets STAT2 and not STAT1 to inhibit type I interferon-stimulated JAK-STAT signaling. Microbes Infect. 2018, 20, 360–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ye, H.; Li, S.; Jiao, B.; Wu, J.; Zeng, P.; Chen, L. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus inhibits exogenous Type I IFN signaling pathway through its NSs invitro. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172744. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa, R.; Sakabe, S.; Urata, S.; Yasuda, J. Species-Specific Pathogenicity of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus Is Determined by Anti-STAT2 Activity of NSs. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e02226-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowen, B.B.; Westover, J.B.; Miao, J.; Van Wettere, A.J.; Rigas, J.D.; Hickerson, B.T.; Jung, K.H.; Li, R.; Conrad, B.L.; Nielson, S.; et al. Modeling Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus Infection in Golden Syrian Hamsters: Importance of STAT2 in Preventing Disease and Effective Treatment with Favipiravir. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e01942-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, S. TRIM Family Proteins: Roles in Autophagy, Immunity, and Carcinogenesis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42, 297–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niida, M.; Tanaka, M.; Kamitani, T. Downregulation of active IKK beta by Ro52-mediated autophagy. Mol. Immunol. 2010, 47, 2378–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Shin, W.J.; Jung, J.U. Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus NSs Interacts with TRIM21 To Activate the p62-Keap1-Nrf2 Pathway. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01684-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gack, M.U.; Albrecht, R.A.; Urano, T.; Inn, K.S.; Huang, I.C.; Carnero, E.; Farzan, M.; Inoue, S.; Jung, J.U.; García-Sastre, A. Influenza A virus NS1 targets the ubiquitin ligase TRIM25 to evade recognition by the host viral RNA sensor RIG-I. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Y.Q.; Ning, Y.J.; Wang, H.; Deng, F. A RIG-I-like receptor directs antiviral responses to a bunyavirus and is antagonized by virus-induced blockade of TRIM25-mediated ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 9691–9711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonczyk, A.; Krist, B.; Sajek, M.; Michalska, A.; Piaszyk-Borychowska, A.; Plens-Galaska, M.; Wesoly, J.; Bluyssen, H.A.R. Direct Inhibition of IRF-Dependent Transcriptional Regulatory Mechanisms Associated With Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriyama, M.; Igarashi, M.; Koshiba, T.; Irie, T.; Takada, A.; Ichinohe, T. Two Conserved Amino Acids within the NSs of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Phlebovirus Are Essential for Anti-interferon Activity. J. Virol. 2018, 92, e00706-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, R.; Guan, Y.; Jiang, N.; Zheng, N.; Wu, Z. Nonstructural Protein NSs Hampers Cellular Antiviral Response through LSm14A during Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus Infection. J. Immunol. 2021, 207, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, J.; Yamada, S.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Abe, H.; Shimojima, M.; Kato, H.; Fujita, T. The Non-structural Protein NSs of SFTSV Causes Cytokine Storm Through the Hyper-activation of NF-κB. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 41, e00542-20. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q.; Jin, C.; Zhu, L.; Liang, M.; Li, C.; Cardona, C.J.; Li, D.; Xing, Z. Host Responses and Regulation by NFκB Signaling in the Liver and Liver Epithelial Cells Infected with A Novel Tick-borne Bunyavirus. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.W.; Chu, M.; Jiao, Y.J.; Zhou, C.M.; Qi, R.; Yu, X.J. SFTSV Infection Induced Interleukin-1β Secretion Through NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 595140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vince, J.E.; De Nardo, D.; Gao, W.; Vince, A.J.; Hall, C.; McArthur, K.; Simpson, D.; Vijayaraj, S.; Lindqvist, L.M.; Bouillet, P.; et al. The Mitochondrial Apoptotic Effectors BAX/BAK Activate Caspase-3 and -7 to Trigger NLRP3 Inflammasome and Caspase-8 Driven IL-1β Activation. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 2339–2353.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.L.; Xin, Q.L.; Guan, Z.Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.A.; Li, X.K.; Xiao, G.F.; Lozach, P.Y.; et al. SFTSV Infection Induces BAK/BAX-Dependent Mitochondrial DNA Release to Trigger NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 4370–4385.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Yu, Y.; Wen, C.; Li, Z.; Ding, H.; Qi, X.; Cardona, C.J.; Xing, Z. Nonstructural Protein NSs Activates Inflammasome and Pyroptosis through Interaction with NLRP3 in Human Microglial Cells Infected with Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Bandavirus. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0016722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Hu, K.; Yi, Z.; Ma, H.; Li, X.; Guo, W.; Xu, B.; Huang, X. Changes in peripheral blood cytokines in patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 4704–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Kang, J.; Xu, L.; Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Hou, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T. The Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus NSs Protein Interacts with CDK1 To Induce G(2) Cell Cycle Arrest and Positively Regulate Viral Replication. J. Virol. 2020, 94, e01575-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.M.; Zhang, W.K.; Yan, L.N.; Jiao, Y.J.; Zhou, C.M.; Yu, X.J. Bunyavirus SFTSV exploits autophagic flux for viral assembly and egress. Autophagy 2022, 18, 1599–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.Y.; Yu, X.J.; Zhou, C.M. SAFA initiates innate immunity against cytoplasmic RNA virus SFTSV infection. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1010070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.K.; Zhang, S.F.; Xu, W.; Xing, B.; Lu, Q.B.; Zhang, P.H.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.C.; Chen, W.W.; et al. Vascular endothelial injury in severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome caused by the novel bunyavirus. Virology 2018, 520, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, P.; Zheng, N.; Liu, Y.; Tian, C.; Wu, X.; Ma, X.; Chen, D.; Zou, X.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; et al. Deficient humoral responses and disrupted B-cell immunity are associated with fatal SFTSV infection. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Li, W.; Li, H.; Jie, S. Circulating regulatory T cells in patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Infect. Dis. 2015, 47, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, A.; Park, S.J.; Jung, K.L.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, E.H.; Kim, Y.I.; Foo, S.S.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.G.; Yu, K.M.; et al. Molecular Signatures of Inflammatory Profile and B-Cell Function in Patients with Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome. mBio 2021, 12, e02583-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, T.; Sato, Y.; Sano, K.; Arashiro, T.; Katano, H.; Nakajima, N.; Shimojima, M.; Kataoka, M.; Takahashi, K.; Wada, Y.; et al. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus targets B cells in lethal human infections. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Fu, Y.; Wang, H.; Guan, Y.; Zhu, W.; Guo, M.; Zheng, N.; Wu, Z. Severe Fever With Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus-Induced Macrophage Differentiation Is Regulated by miR-146. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, A.; Michel, T.; Thérésine, M.; Andrès, E.; Hentges, F.; Zimmer, J. CD56bright natural killer (NK) cells: An important NK cell subset. Immunology 2009, 126, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xiong, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, S.; Zou, C.; Liang, B.; Lu, M.; et al. Depletion but Activation of CD56(dim)CD16(+) NK Cells in Acute Infection with Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus. Virol. Sin. 2020, 35, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, J.D.; Cameron, C.E. Mechanisms of action of ribavirin against distinct viruses. Rev. Med. Virol. 2006, 16, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Lu, Q.B.; Cui, N.; Li, H.; Wang, L.Y.; Liu, K.; Yang, Z.D.; Wang, B.J.; Wang, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; et al. Case-fatality ratio and effectiveness of ribavirin therapy among hospitalized patients in china who had severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2013, 57, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łagocka, R.; Dziedziejko, V.; Kłos, P.; Pawlik, A. Favipiravir in Therapy of Viral Infections. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Jiang, X.M.; Cui, N.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, S.F.; Lu, Q.B.; Yang, Z.D.; Xin, Q.L.; Song, Y.B.; Zhang, X.A.; et al. Clinical effect and antiviral mechanism of T-705 in treating severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, H.; Shimojima, M.; Fukushi, S.; Yoshikawa, T.; Fukuma, A.; Taniguchi, S.; Morikawa, S.; Saijo, M. Characterization of Glycoprotein-Mediated Entry of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 5292–5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, W. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) treated with a novel antiviral medication, favipiravir (T-705). Infection 2020, 48, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suemori, K.; Saijo, M.; Yamanaka, A.; Himeji, D.; Kawamura, M.; Haku, T.; Hidaka, M.; Kamikokuryo, C.; Kakihana, Y.; Azuma, T.; et al. A multicenter non-randomized, uncontrolled single arm trial for evaluation of the efficacy and the safety of the treatment with favipiravir for patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2021, 15, e0009103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Lu, Q.B.; Yao, W.S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.A.; Cui, N.; Yuan, C.; Yang, T.; Peng, X.F.; Lv, S.M.; et al. Clinical efficacy and safety evaluation of favipiravir in treating patients with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. EBioMedicine 2021, 72, 103591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Chan, J.F.; Ye, Z.W.; Wen, L.; Tsang, T.G.; Cao, J.; Huang, J.; Chan, C.C.; Chik, K.K.; Choi, G.K.; et al. Screening of an FDA-Approved Drug Library with a Two-Tier System Identifies an Entry Inhibitor of Severe Fever with Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus. Viruses 2019, 11, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Zhang, L.K.; Li, S.F.; Zhang, S.F.; Wan, W.W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Xin, Q.L.; Dai, K.; Hu, Y.Y.; Wang, Z.B.; et al. Calcium channel blockers reduce severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV) related fatality. Cell Res. 2019, 29, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hover, S.; Foster, B.; Barr, J.N.; Mankouri, J. Viral dependence on cellular ion channels—An emerging anti-viral target? J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hover, S.; King, B.; Hall, B.; Loundras, E.A.; Taqi, H.; Daly, J.; Dallas, M.; Peers, C.; Schnettler, E.; McKimmie, C.; et al. Modulation of Potassium Channels Inhibits Bunyavirus Infection. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 3411–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kursunel, M.A.; Esendagli, G. The untold story of IFN-γ in cancer biology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2016, 31, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thäle, C.; Kiderlen, A.F. Sources of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) in early immune response to Listeria monocytogenes. Immunobiology 2005, 210, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlrab, F.; Jamieson, A.T.; Hay, J.; Mengel, R.; Guschlbauer, W. The effect of 2′-fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine on herpes virus growth. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA) Gene Struct. Expr. 1985, 824, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smee, D.F.; Jung, K.-H.; Westover, J.; Gowen, B.B. 2′-Fluoro-2′-deoxycytidine is a broad-spectrum inhibitor of bunyaviruses in vitro and in phleboviral disease mouse models. Antivir. Res. 2018, 160, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, M.; Shirasago, Y.; Tanida, I.; Kakuta, S.; Uchiyama, Y.; Shimojima, M.; Hanada, K.; Saijo, M.; Fukasawa, M. Structural basis of antiviral activity of caffeic acid against severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus. J. Infect. Chemother. Off. J. Jpn. Soc. Chemother. 2021, 27, 397–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.-P.; Tsui, K.-H.; Chang, K.-S.; Sung, H.-C.; Hsu, S.-Y.; Lin, Y.-H.; Yang, P.-S.; Chen, C.-L.; Feng, T.-H.; Juang, H.-H. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester inhibits the growth of bladder carcinoma cells by upregulating growth differentiation factor 15. Biomed. J. 2022, 45, 763–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Xiaokaiti, Y.; Fan, S.; Pan, Y.; Li, X.; Li, X. Direct interaction between caffeic acid phenethyl ester and human neutrophil elastase inhibits the growth and migration of PANC-1 cells. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 3019–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X.; Liu, X.; Xuan, H. Ethanol extract of propolis and its constituent caffeic acid phenethyl ester inhibit breast cancer cells proliferation in inflammatory microenvironment by inhibiting TLR4 signal pathway and inducing apoptosis and autophagy. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanida, I.; Shirasago, Y.; Suzuki, R.; Abe, R.; Wakita, T.; Hanada, K.; Fukasawa, M. Inhibitory Effects of Caffeic Acid, a Coffee-Related Organic Acid, on the Propagation of Hepatitis C Virus. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 68, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Yamashita, A.; Nakakoshi, M.; Yokoe, H.; Sudo, M.; Kasai, H.; Tanaka, T.; Fujimoto, Y.; Ikeda, M.; Kato, N.; et al. Inhibitory Effects of Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester Derivatives on Replication of Hepatitis C Virus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, M.; Shirasago, Y.; Ando, S.; Shimojima, M.; Saijo, M.; Fukasawa, M. Caffeic acid, a coffee-related organic acid, inhibits infection by severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in vitro. J. Infect. Chemother. 2018, 24, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWald, L.E.; Johnson, J.C.; Gerhardt, D.M.; Torzewski, L.M.; Postnikova, E.; Honko, A.N.; Janosko, K.; Huzella, L.; Dowling, W.E.; Eakin, A.E.; et al. In Vivo Activity of Amodiaquine against Ebola Virus Infection. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Mesplède, T.; Xu, H.; Quan, Y.; Wainberg, M.A. The antimalarial drug amodiaquine possesses anti-ZIKA virus activities. J. Med. Virol. 2018, 90, 796–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baba, M.; Toyama, M.; Sakakibara, N.; Okamoto, M.; Arima, N.; Saijo, M. Establishment of an antiviral assay system and identification of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus inhibitors. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2017, 25, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.R.; Kim, T.J.; Heo, S.T.; Hwang, K.A.; Oh, H.; Ha, T.; Ko, H.K.; Baek, S.; Kim, J.E.; Kim, J.H.; et al. IL-6 and IL-10 Levels, Rather Than Viral Load and Neutralizing Antibody Titers, Determine the Fate of Patients With Severe Fever With Thrombocytopenia Syndrome Virus Infection in South Korea. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 711847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Yi, J.; Kim, G.; Choi, S.J.; Jun, K.I.; Kim, N.H.; Choe, P.G.; Kim, N.J.; Lee, J.K.; Oh, M.D. Severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome, South Korea, 2012. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1892–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Azuma, M.; Maruhashi, T.; Sogabe, K.; Sumitani, R.; Uemura, M.; Iwasa, M.; Fujii, S.; Miki, H.; Kagawa, K.; et al. Steroid pulse therapy in patients with encephalopathy associated with severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. J. Infect. Chemother. 2018, 24, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.R.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, Y.R.; Lee, K.H.; Oh, W.S.; Heo, S.T. Application of therapeutic plasma exchange in patients having severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, V. An Overview of Monoclonal Antibodies. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 35, 150927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Du, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhan, L.; Yang, B.; Huang, X.; Xu, B.; Morita, K.; Yu, F. Development of monoclonal antibody based IgG and IgM ELISA for diagnosis of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus infection. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 26, 102386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, S.; Posadas-Herrera, G.; Aoki, K.; Morita, K.; Hayasaka, D. Therapeutic effect of post-exposure treatment with antiserum on severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS) in a mouse model of SFTS virus infection. Virology 2015, 482, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa, T.; Taniguchi, S.; Kato, H.; Iwata-Yoshikawa, N.; Tani, H.; Kurosu, T.; Fujii, H.; Omura, N.; Shibamura, M.; Watanabe, S.; et al. A highly attenuated vaccinia virus strain LC16m8-based vaccine for severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1008859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, J.E.; Kim, Y.I.; Park, S.J.; Yu, M.A.; Kwon, H.I.; Eo, S.; Kim, T.S.; Seok, J.; Choi, W.S.; Jeong, J.H.; et al. Development of a SFTSV DNA vaccine that confers complete protection against lethal infection in ferrets. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Ye, M.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Li, H.; Peng, K. Screening of a Small Molecule Compound Library Identifies Toosendanin as an Inhibitor Against Bunyavirus and SARS-CoV-2. Front. Pharm. 2021, 12, 735223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).