Hepatitis B among University Population: Prevalence, Associated Risk Factors, Knowledge Assessment, and Treatment Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population and Blood Sampling

2.2. Laboratory Testing

2.3. HBV DNA Extraction and Amplification

- Forward: 50-CATCCTGCTGCTATGCCTCATCT-30

- Reverse: 50-CGAACCACTGAACAAATGGCACT-30

- Forward: 50-GGTATGTTGCCCGTTTGTCCTCT-30

- Reverse: 50-GGCACTAGTAAACTGAGCCA-30

2.4. Liver Function Tests (LFTs) and International Normalized Ratio (INR)

2.5. Detection of HBeAg

2.6. Risk Factors and Knowledge Assessment

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Treatment Management for Hepatitis B

3. Results

3.1. Overall Prevalence of Hepatitis B

3.2. Age-Wise Prevalence of Hepatitis B

3.3. Prevalence of Hepatitis B Regarding Social Status of the Participants

3.4. Viral Load of the PCR-Positive Individuals

3.5. Liver Function Tests (LFTs) of the HBV-Positive Individuals

3.6. Prothrombin Time Test (PT-Test) or International Normalized Ratio (INR) (n = 39)

3.7. Risk Factor Assessment Associated with Hepatitis B Spread among Studied Population

3.8. Knowledge Assessment of the Participants before and after Awareness

3.9. Prevalence of Hepatitis B among Different Tribes

3.10. Previous Medical History of the Participants

3.11. Treatment Management for the Acute and Chronic HBV-Postive Participants

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Idrees, M.; Khan, S.; Riazuddin, S. Common genotypes of hepatitis B virus. J. Coll. Phys. Surg. Pak. 2004, 14, 344–347. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.; Zhang, H.; Yu, H.; Li, H.; Ling, Y.Q.; Hu, X.Q.; Zhu, H.G. Hepatitis B virus mutations associated with in situ expression of hepatitis B core antigen, viral load and prognosis in chronic hepatitis B patients. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2008, 204, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, L.; Idrees, M.; Ali, M.; Rehman, I.; Hussain, A.; Afzal, S.; Butt, S.; Saleem, S.; Munir, S.; Badar, S. An overview of treatment response rates to variousanti-viral drugs in Pakistani Hepatitis B Virus infected patients. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, W.; Guo, F.; Xuc, S.; Zhaod, N.; Chena, S.; Liu, L. A novel real-time PCR assay for determination of viral loads in person infected with hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. Methods 2010, 165, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskevis, D.; Haida, C.; Tassopoulos, N.; Raptopoulou, M.; Tsantoulas, D.; Papachristou, H.; Sypsa, V.; Hatzakis, A. Development and assessment of a novel real-time PCR assay for quantitation of HBV DNA. J. Virol. Methods 2002, 103, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Zaidi, S.Z.; Malik, S.A.; Naeem, A.; Shaukat, S.; Sharif, S.; Angez, M.; Khan, A.; Butt, J.A. Serology based disease status of Pakistani population infected with Hepatitis B virus. BMC Infect. Dis. 2007, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beasley, R.P.; Trepo, C.; Stevens, C.E.; Szmuness, W. The e antigen and vertical transmission of hepatitis B surface antigen. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1977, 105, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, M.J.; Ahtone, J.; Weisfuse, I.; Starko, K.; Vacalis, T.D.; Maynard, J.E. Hepatitis B virus transmission between heterosexuals. JAMA 1986, 256, 1307–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, L.A.; Rinaldo, C.R.; Lyter, D.W.; Valdiserri, R.O.; Belle, S.H.; Ho, M. Sexual transmission efficiency of hepatitis B virus and human immunodeficiency virus among homosexual men. JAMA 1990, 264, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broers, B.; Junet, C.; Bourquin, M.; Déglon, J.J.; Perrin, L.; Hirschel, B. Prevalence and incidence rate of HIV, hepatitis B and C among drug users on methadone maintenance treatment in Geneva between 1988 and 1995. AIDS 1998, 12, 2059–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, A.; Lloyd, J.; Zaffran, M.; Simonsen, L.; Kane, M. Transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency viruses through unsafe injections in the developing world: Model-based regional estimates. Bull. World Health Organ. 1999, 77, 801. [Google Scholar]

- Komas, N.P.; Bai-Sepou, S.; Manirakiza, A.; Leal, J.; Bere, A.; Le Faou, A. The Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus Markers in a Cohort of Students in Bangui, Central African Republic. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mboto, C.I.; Edet, E.J. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Hepatitis B Virus Infection among Students in University of Uyo. Int. J. Mod. Biol. Med. 2012, 2, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Pido, B.; Kagimu, M. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection among Makerere University medical students. Afr. Health Sci. 2005, 5, 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tawiah, P.A.; Abaka-Yawson, A.; Effah, E.S.; Arhin-Wiredu, K.; Oppong, K. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis B virus infection among medical laboratory science students in a Ghanaian tertiary institution. J. Health Res. 2022, 36, 442–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, A.S.; Hakim, S.T.; McLean, D.; Kazmi, S.U.; Bagasra, O. Prevalence of Hepatitis B virus genotype D in females in Karachi, Pakistan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctr. 2008, 2, 373–378. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim, S.T.; Kazmi, S.U.; Bagasra, O. Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B and C Genotypes Among Young Apparently Healthy Females of Karachi Pakistan. Libyan J. Med. 2008, 3, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepatitis Prevention & Control Program Sindh (Chief Minister’s Initiative) 2009; Directorate General Health Services: Hyderabad, Pakistan, 2009.

- Hassali, M.A.; Shafie, A.A.; Saleem, F.; Farooqui, M.; Aljadhey, H. A cross sectional assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice towards Hepatitis B among healthy population of Quetta, Pakistan. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 692. [Google Scholar]

- Soomar, S.M.; Siddiqui, A.R.; Azam, S.I.; Shah, M. Determinants of hepatitis B vaccination status in health care workers of two secondary care hospitals of Sindh, Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 5579–5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaullah, S.; Khan, S.; Ayaz, S.; Khan, S.N.; Ali, I.; Hoti, N.; Siraj, S. Prevalence of HBV and HBV vaccination coverage in health care workers of tertiary hospitals of Peshawar, Pakistan. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Nadeem, M.S.; Arshad, M.; Riaz, H.; Latif, M.M.; Iqbal, M.; Latif, M.Z.; Nisar, A.; Shakoori, A.R. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus in the general population of Hill Surang area, Azad Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan. Pak. J. Zool. 2013, 45, 543–548. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, M.; Sanders, E.; Aitken, C. Seroprevalence of hepatitis markers: HAV, HBV, HCV and HEV among primary school children in Freetown Sierra Leon. West Afr. J. Med. 1998, 17, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Odinachi, O.E.; John, D.M.; Augustine, U.; Ogbonnaya, O.; Felicia, N.O.; Maduka, V.A.; Agwu, U.N. Prevalence of Hepatitis B surface antigen among the newly admitted students of University of Jos, Nigeria. Am. J. Life Sci. 2014, 2, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Alter, M. Epidemiology and prevention of hepatitis B. Semin. Liver Dis. 2003, 23, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, X.; Yingjun, Z.; Adrian, L.; Biao, C.; Dongqing, Y.; Feng, H.; Xiaorong, S.; Fuyang, G.; Liu, X.; Shun, L.; et al. Hepatitis B virus infections and risk factors among the general population in Anhui Province, China: An epidemiological study. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, T.; Ersin, U.E.; Akcam, F.Z. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen and its correlation with risk factors among new recruits in Turkey. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 16, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Muhammad, I.; Liaqat, A.; Abrar, H.; Irshad, R.; Sana, S.; Samia, A.; Sadia, B. Hepatitis B virus in Pakistan: A systematic review of prevalence, risk factors, awareness status and genotypes. Virol. J. 2011, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.R. Epidemiology of Hepatitis B in the United States. Hepatology 2009, 49, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, Y.; Matsuoka, H.; Kawaguchi, T.; Ide, T.; Sata, M. HBV and HCV infection in Japanese dental care workers. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2008, 21, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Satomi, T.; Wannapa, S.I.; Danai, T. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infection in rural ethnic populations of Northern Thailand. J. Clin. Virol. 2002, 24, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganczak, M.; Dmytrzyk-Daniłów, G.; Korzeń, M.; Drozd-Dąbrowska, M.; Szych, Z. Prevalence of HBV Infection and Knowledge of Hepatitis B Among Patients Attending Primary Care Clinics in Poland. J. Commun. Health 2016, 41, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mesfin, Y.M.; Kibret, K.T. Assessment of Knowledge and Practice towards Hepatitis B among Medical and Health Science Students in Haramaya University, Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sannathimmappa, M.B.; Nambiar, V.; Arvindakshan, R. Hepatitis B: Knowledge and awareness among preclinical year medical students. Avicenna J. Med. 2019, 9, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.; Pham, T.; So, S.; Hoang, T.; Nguyen, T.; Ngo, T.B.; Nguyen, M.P.; Thai, Q.H.; Nguyen, N.K.; Le Ho, T.; et al. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices toward Hepatitis B Virus Infection among Students of Medicine in Vietnam. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

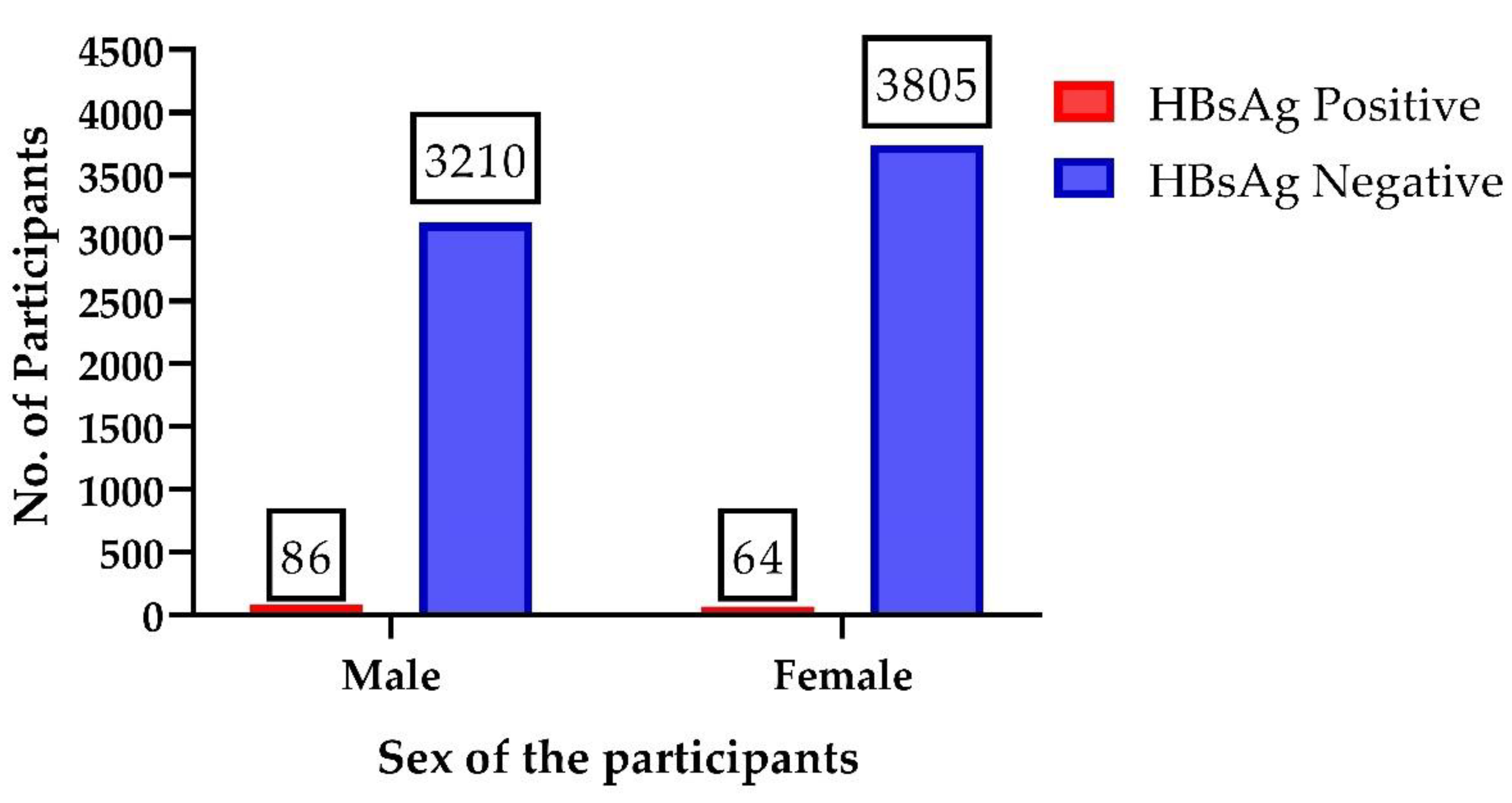

| Sex | Total Participants | HBsAg Positive | HBsAg Negative | HBV Positive | HBV Negative | HBeAg Positive | HBeAg Negative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 3210 | 86 | 3124 | 32 | 54 | 1 | 31 |

| Female | 3805 | 64 | 3786 | 7 | 57 | 1 | 6 |

| Age Groups | No. of Individuals | Standard Deviation | Median Age | Mode of Age | Mean Age with 95% (Z* = 1.96) Confidence Interval (CI) | HBsAg-Positive Individuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16–30 | 6270 | 3.3 | 21 | 21 | 21.5 ± 0.08 | 138 (2.2%) |

| 31–45 | 504 | 13.9 | 36 | 35 | 36.8 ± 1.2 | 0 |

| 46–60 | 228 | 27.9 | 50 | 50 | 51.4 ± 3.6 | 12 (5.3%) |

| Above 60 | 13 | 40.1 | 63 | 63 | 63.6 ± 21.8 | 0 |

| Total Population | 7015 | 7.2 | 22 | 21 | 23.7 ± 0.17 | 150 (2.13) |

| Population Distribution | No. of Individuals | Prevalence of HBsAg | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employees | 493 | 47 | 9.5% |

| Students | 6522 | 103 | 1.6% |

| Total | 7015 | 150 | 2.13% |

| Viral Load | No. of Individuals | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| <10,000 IU/mL | 0 | 0% |

| 10,000–20,000 IU/mL | 9 | 23.1% |

| >20,000 IU/mL | 30 | 76.9% |

| Test | Normal Range | No. of Individuals within Normal Range | % | No. of Individuals above Normal Range | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin | 0.2–1.0 mg/dL | 18 | 46.2 | 21 | 53.8 |

| ALT | Male 0–43 U/L | ||||

| Female 0–36 U/L | |||||

| ALP | Adult 80–306 U/L | ||||

| Child up to 645 U/L |

| Prothrombin Time | INR = (PT Patient/PT Normal)ISI | Indications | No. of Individuals (n = 17) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Below 11 s | <0.8 | Hyperprothrombinemia | 0 | 0 |

| 11 to 13.5 s | 0.8 to 1.1 | Normal | 36 | 92.3 |

| Above 13.5 s | >1.1 | Hypoprothrombinemia | 03 | 7.7 |

| Factors | Responses | Overall Responses | Frequencies Diseased | Frequencies Non-Diseased | p-Value (0.05) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jaundice/hepatitis history | Yes | 100 (1.4%) | 02 | 98 | 0.9 | No |

| No | 7005 (98.6%) | 148 | 6767 | |||

| Vaccination against hepatitis | Yes | 21 (0.3%) | 0 | 21 | 0.49 | No |

| No | 6994 (99.7%) | 150 | 6844 | |||

| History of blood transfusion | Yes | 1170 (16.7%) | 30 | 1140 | 0.27 | No |

| No | 5845 (83.3%) | 120 | 5725 | |||

| Dental treatment | Yes | 2630 (37.5%) | 76 | 2554 | 0.0008 | Yes |

| No | 4385 (62.5%) | 74 | 4311 | |||

| Surgery (minor/major) | Yes | 3309 (47.2%) | 78 | 3231 | 0.2 | No |

| No | 3706 (52.8%) | 72 | 3634 | |||

| History of injections | Yes | 7015 (100%) | 150 | 6865 | 0 | No |

| No | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Sharing of comb, nail cutter, etc. | Yes | 7015 (100%) | 150 | 6865 | 0 | No |

| No | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Visit to beauty parlor/barber shop | Yes | 7015 (100%) | 150 | 6865 | 0 | No |

| No | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 | |||

| Hospitalization history | Yes | 3309 (47.2%) | 85 | 3224 | 0.018 | Yes |

| No | 3706 (52.8%) | 65 | 3641 | |||

| Other diseases, i.e., diabetes/T.B or any other | Yes | 656 (9.4%) | 01 | 655 | 0.0002 | Yes |

| No | 6359 (90.6%) | 149 | 6210 | |||

| Organ transplantation | Yes | 02 (0.03%) | 0 | 02 | 0.8 | No |

| No | 7013 (99.97%) | 150 | 6863 | |||

| Use of contaminated mourning blades | Yes | 27 (0.38%) | 27 | 0 | <0.0001 | Yes |

| No | 6988 (99.62%) | 123 | 6865 | |||

| Tattooing/piercing on any part of the body | Yes | 4381 (62.5%) | 123 | 4258 | <0.0001 | Yes |

| No | 2634 (37.5%) | 27 | 2585 |

| Questions | Before Awareness | After Awareness | Chi- Square (p = 0.05, CI = 95% and df = 1) | Fisher’s Exact Test (p = 0.05 and CI = 95%) | Statistical Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Yes | No | ||||

| Have you ever heard of a disease termed as hepatitis? | 2570 (36.6%) | 4445 (63.4%) | 7015 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Have you ever heard of a disease termed as hepatitis B? | 2570 (36.6%) | 4445 (63.4%) | 7015 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Is hepatitis B a viral disease? | 2570 (36.6%) | 4445 (63.4%) | 7015 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Can hepatitis B affect liver function? | 1940 (27.6%) | 5075 (72.4%) | 7015 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Can hepatitis B cause liver Cancer? | 1207 (17.2%) | 5808 (82.8%) | 6200 (88.4%) | 815 (11.6%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Can hepatitis B affect any age group? | 641 (9.1%) | 6374 (90.9%) | 6033 (86%) | 982 (14%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| The early symptoms of hepatitis B are the same as cold and flu (fever, running nose, cough) | 5069 (72.3%) | 1946 (27.7%) | 187 (2.6%) | 6828 (97.4%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Jaundice is one of the common symptoms of hepatitis B? | 1946 (27.7%) | 5069 (72.3%) | 7015 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Are nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite common symptom of hepatitis B? | 1533 (21.8%) | 5482 (78.2%) | 6828 (97.4%) | 187 (2.6%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Are there no symptoms of hepatitis B in some of the patients? | 281 (4.0%) | 6734 (9.6%) | 5083 (72.5%) | 1932 (27.5%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Can hepatitis B be transmitted by un-sterilized syringes, needles, and surgical instruments? | 2570 (36.6%) | 4445 (63.4%) | 7015 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Can hepatitis B be transmitted by contaminated blood and blood products? | 2570 (36.6%) | 4445 (63.4%) | 7015 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Can hepatitis B be transmitted by using blades of the barber/ear and nose piercing? | 2570 (36.6%) | 4445 (63.4%) | 7015 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Can hepatitis B be transmitted by sharing of jewelry? | 0 (100%) | 7015 (100%) | 5055 (72%) | 1960 (28%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Can hepatitis B be transmitted from mother to child? | 2003 (28.6%) | 5012 (71.4%) | 7015 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Can hepatitis B be transmitted by contaminated water/food prepared by person suffering with these infections? | 4445 (63.4%) | 2570 (36.6%) | 0 (0%) | 7015 (100%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Is hepatitis B curable/treatable? | 1117 (15.9%) | 5898 (84.1%) | 6001 (85.5%) | 1014 (14.5) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Can hepatitis B be self-cured by body? | 3568 (50.8%) | 3447 (49.2%) | 1101 (15.7%) | 5909 (84.3%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Is vaccination available for hepatitis B? | 5270 (75.2%) | 1745 (24.8%) | 7015 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Is a specific diet required for the treatment of hepatitis B? | 4405 (52.8%) | 2610 (37.2%) | 6067 (86.5%) | 948 (13.5%) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | Yes |

| Caste | No. of Individuals per Tribe | No. of HBsAg-Positive Individuals |

|---|---|---|

| Abbasi | 421 | 10 (2.4%) |

| Awan | 788 | 18 (2.3%) |

| Balti | 105 | -- |

| Chaudhary | 568 | 4 (0.7%) |

| Khawaja | 936 | 22 (2.4%) |

| Mughal | 688 | 06 (0.9%) |

| Pakhtoon | 233 | -- |

| Peerzada | 32 | -- |

| Qureshi | 245 | 4 (1.6%) |

| Rajpoot | 1635 | 21 (1.3%) |

| Sheikh | 183 | 1 (0.5%) |

| Sudhan | 310 | 3 (0.9%) |

| Syed | 871 | 61 (7.0%) |

| Total Tribes= 13 | Total No. Individuals = 7015 | Total HBsAg Positive = 150 (2.13%) |

| Medical History | No. of Individuals | Male Individuals | Female Individuals |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBV Vaccination | 21 (0.3%) | 14 (66.6%) | 7 (33.4%) |

| Hepatitis A | 58 (0.8%) | 50 (86.2%) | 8 (13.8%) |

| Jaundice | 100 (1.4%) | 79 (79%) | 21 (21%) |

| Hypocalcemia | 170 (2.4%) | 165 (97%) | 5 (03%) |

| Tuberculosis | 656 (9.4%) | 231 (35.2%) | 425 (64.8%) |

| Dental Surgery | 2630 (37.5%) | 1894 (72%) | 736 (28%) |

| Transplantation | 2 (0.03%) | 1 (50%) | 1 (50%) |

| Gastric Ulcer | 41 (0.6%) | 5 (12.2%) | 36 (87.8%) |

| Gall Bladder Surgery | 9 (0.2%) | 3 (33.4%) | 6 (66.6%) |

| Typhoid | 438 (6.2%) | 322 (73.5%) | 116 (26.5%) |

| Chicken Pox | 45 (0.6%) | 31 (68.9%) | 14 (31.1%) |

| Vision Abnormalities | 85 (1.2%) | 39 (45.8%) | 46 (54.2%) |

| Renal Stones | 13 (0.2%) | 12 (92.3%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Appendicitis | 162 (2.3%) | 122 (75.3%) | 40 (24.7%) |

| Any Allergy | 261 (3.7%) | 143 (54.8%) | 118 (45.2%) |

| Cardiac Problems | 5 (0.07%) | 5 (100%) | -- |

| Pneumonia | 7 (0.09%) | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (71.4%) |

| Measles | 3 (0.04%) | 1 (33.4%) | 2 (66.6%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kazmi, S.A.; Rauf, A.; Alshahrani, M.M.; Awadh, A.A.A.; Iqbal, Z.; Soltane, R.; Tag-Eldin, E.; Ahmad, A.; Ansari, Z.; Zia-ur-Rehman. Hepatitis B among University Population: Prevalence, Associated Risk Factors, Knowledge Assessment, and Treatment Management. Viruses 2022, 14, 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14091936

Kazmi SA, Rauf A, Alshahrani MM, Awadh AAA, Iqbal Z, Soltane R, Tag-Eldin E, Ahmad A, Ansari Z, Zia-ur-Rehman. Hepatitis B among University Population: Prevalence, Associated Risk Factors, Knowledge Assessment, and Treatment Management. Viruses. 2022; 14(9):1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14091936

Chicago/Turabian StyleKazmi, Syed Ayaz, Abdul Rauf, Mohammed Merae Alshahrani, Ahmed Abdullah Al Awadh, Zahoor Iqbal, Raya Soltane, ElSayed Tag-Eldin, Altaf Ahmad, Zulqarnain Ansari, and Zia-ur-Rehman. 2022. "Hepatitis B among University Population: Prevalence, Associated Risk Factors, Knowledge Assessment, and Treatment Management" Viruses 14, no. 9: 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14091936

APA StyleKazmi, S. A., Rauf, A., Alshahrani, M. M., Awadh, A. A. A., Iqbal, Z., Soltane, R., Tag-Eldin, E., Ahmad, A., Ansari, Z., & Zia-ur-Rehman. (2022). Hepatitis B among University Population: Prevalence, Associated Risk Factors, Knowledge Assessment, and Treatment Management. Viruses, 14(9), 1936. https://doi.org/10.3390/v14091936