Abstract

Retroviruses must selectively recognize their unspliced RNA genome (gRNA) among abundant cellular and spliced viral RNAs to assemble into newly formed viral particles. Retroviral gRNA packaging is governed by Gag precursors that also orchestrate all the aspects of viral assembly. Retroviral life cycles, and especially the HIV-1 one, have been previously extensively analyzed by several methods, most of them based on molecular biology and biochemistry approaches. Despite these efforts, the spatio-temporal mechanisms leading to gRNA packaging and viral assembly are only partially understood. Nevertheless, in these last decades, progress in novel bioimaging microscopic approaches (as FFS, FRAP, TIRF, and wide-field microscopy) have allowed for the tracking of retroviral Gag and gRNA in living cells, thus providing important insights at high spatial and temporal resolution of the events regulating the late phases of the retroviral life cycle. Here, the implementation of these recent bioimaging tools based on highly performing strategies to label fluorescent macromolecules is described. This report also summarizes recent gains in the current understanding of the mechanisms employed by retroviral Gag polyproteins to regulate molecular mechanisms enabling gRNA packaging and the formation of retroviral particles, highlighting variations and similarities among the different retroviruses.

1. Introduction

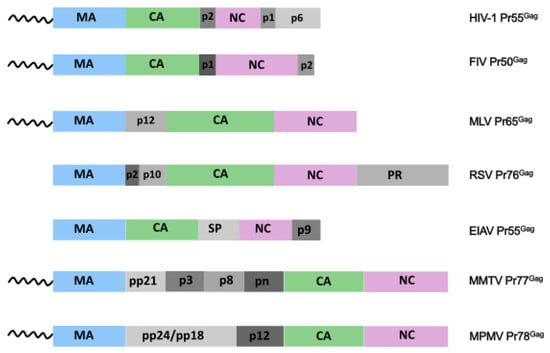

Retroviral assembly is a finely tuned process that requires viral and cellular factors to converge at the right time at defined cellular sites to be efficiently achieved. To generate an infectious particle, retroviruses must selectively package two homologous copies of their single stranded gRNA of positive polarity that are non-covalently linked through intermolecular base-pairing. The dimeric gRNA is selected from a much larger pool of cellular and sub genomic viral RNA moieties (for reviews see [1,2,3]), and this specific selection is achieved through the recognition of cis-acting genomic packaging signals (Psi or ψ) by the main structural polyprotein Gag. Retroviral Gag are present in all the members of the Retroviridae family (for reviews see [4,5,6,7]), and their expression is considered as sufficient for the in vitro assembly of retroviral like-particles (VLPs). To this aim, Gag polyproteins employ mechanisms involving their structural domains in association with several viral and host factors including lipid membranes, proteins and RNAs. Some determinants for gRNA encapsidation as gRNA dimerization are common to all different types of retroviruses. On the other hand, retroviruses display two major pathways of assembly: B/D-type retroviruses, such as the Mason-Pfizer Monkey Virus (MPMV), assemble immature procapsids at a pericentriolar location, which are then trafficked to the plasma membrane (PM) where budding takes place [8], while C-type retroviruses, such as the lentivirus Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV-1) and gammaretroviruses as the Murine Leukemia Virus (MLV), assemble and bud from sites on PM.

Retroviral life cycles, and especially the HIV-1 one, have been previously studied by combining tools derived from biochemistry, molecular biology, genetic and structural biology; however, these methods have only yielded a partly incomplete spatio-temporal view of gRNA packaging and retroviral assembly. However, in the last decades, several bioimaging tools provided important insights gained from the direct visualization of viral processes in live cells. Quantitative bioimaging microscopic approaches based on the fluorescent labelling of the different viral components (e.g., Gag and viral RNA) resulted in considerable gains in our knowledge of molecular mechanisms leading to the formation of retroviral particles. Accordingly, data acquired in the lasts 20 years allowed for the monitoring of the real-time intracellular movements of retroviral Gag-gRNA complexes, and provided new understandings at high spatial resolution of determinants regulating the accumulation of ribonucleoprotein complexes at the budding sites at PM [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

HIV-1 is the most well characterized retrovirus, as attested by a huge amount of studies [10,12,14,21,22,23]. Here, the current knowledge based on these recent quantitative microscopic methods of when and where retroviral HIV-1 Gag proteins recruit the gRNA dimer for encapsidation and orchestrate the assembly of the viral particle is summarized. Finally, in this review, variations and similarities between HIV-1 and other retroviruses, as the prototypic simple retroviruses MLV and Rous Sarcoma Virus (RSV) as well as the complex Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV), are also presented.

3. Gag Oligomerization

Biochemical assays and electron microscopy studies previously indicated the presence of HIV-1 Gag cytoplasmic oligomers [75,76], even though the characterization of their stoichiometry had been rather controversial. In addition, epifluorescence microscopy combined with FRAP (fluorescence recovery after photobleaching) displayed the presence of highly mobile cytoplasmic HIV-1 Gag, likely corresponding to monomers or low-order multimers [26,77]. Conversely, fluorescent fluctuations spectroscopy (FFS) techniques pointed out low-diffusing Gag species (D = 0.014 ± 0.002 µm2/s) [14], and both populations were found to nucleate and grow at the assembly sites [11,12,14]. Quantitative-FRET microscopy analysis at PM showed that the disruption of the HIV-1 CA-CTD strongly reduced Gag multimerization, while mutations in NC displayed less-severe defects, thus conferring to these two domains an order of importance in Gag oligomerization [78]. Moreover, truncated Gag proteins, where either the complete NC domain or the NC basic residues were deleted, displayed high cytoplasmic mobility (D = 6.0 ± 1.2 µm2/s), which is consistent with the resulting impaired interactions with gRNA and the affected production of viral particles [14]. Therefore, even though RNA does not seem to be mandatory for Gag oligomerization per se, RNA displays a structural scaffolding role that facilitates Gag multimerization through NC, which is in line with several in vitro findings [50,79,80,81,82]. Interestingly, CA and p2 domains were found to be involved in gRNA packaging [83,84], and thus, in turn, HIV-1 Gag multimerization might play a role in the interaction with gRNA in the cytoplasm [25] or at the PM [85]. Conversely, advanced FFS methods showed that an HIV-1 Gag protein defective in membrane binding (Gag G2A) displays in the cytosol similar RNA biding properties and a similar oligomeric state compared to the native form of Gag [14,21,86].

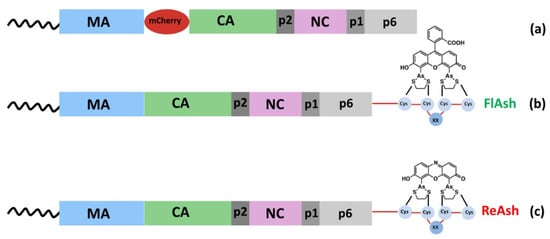

By combining two-photon FRET and FFS, Larson et al. [70] observed RSV Gag multimers in the cytoplasm and also at the PM. Finally, the cytosolic diffusion of monomeric HIV-1 Gag labelled with m-Cherry or Venus fluorescent proteins (D = 2.8 ± 0.5 µm2/s) [14], the diffusion of GFP-tagged RSV Gag proteins diffusing in chicken fibroblast cells (D = 3.2 ± 0.6 µm2/s) [17], and the diffusion of EYFP-tagged HTLV-1 Gag (D = ∼1–3 µm2/s) [86] were found to be similar.

5. Visualization of gRNA Dimer in Cell

Recently, fluorescent RNA labelling techniques have been largely used to monitor HIV-1 RNA in the living cell [12,14,15,23,114]. One of the most widely used strategies to visualize RNA in cells consists in introducing stem-loops that are recognized with high affinity and specificity by the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein which is tagged with a fluorescent protein (e.g., GFP). Multiple copies of this stem-loop motif (usually n = 24) are thus inserted into the target RNA, which is then expressed in cells in parallel of the nuclear MS2–GFP fusion protein. Thus, RNAs carrying the MS2 stem–loops bind MS2–GFP fusion proteins in the nucleus, and this fluorescent complex then moves to the cytoplasm, where it can be visualized. In an attempt to visualize HIV-1 genomes in cells, several groups inserted MS2 stem-loops within the gag intron in order to label only unspliced viral mRNA [10,11,21,114,115,116]. Importantly, these modified viral genomes are efficiently incorporated into virions and are compatible with the production of infectious virions.

The group of Hu also engineered HIV-1 genomes containing binding sites for BglG, an antitermination protein in the E. Coli bgl operon to obtain, together with the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein labelling, simultaneous double RNA labelling with two distinct fluorescent proteins. This strategy provided evidence that virions can contain RNAs derived from different parental viruses, and this occurs at ratios expected from a random distribution [117]. In addition, this team used similar labelling to analyze the cytosolic diffusion of HIV-1 RNA [22]. The transport of cellular mRNA in the cytoplasm is indeed a complex process, and mRNAs can be transported either by passive diffusion, or by directional movement that is reminiscent of an active transport along the cytoskeleton likely depending on the microtubule network (reviewed in [118,119]). Chen et al. [22] thus measured by single-molecule tracking the cytosolic diffusion coefficient of Bgl-YFP–labeled HIV-1 RNA in HeLa cells (D = 0.07 − 0.3 µm2/s), and observed that gRNA mobility is non-directional, but random and indicative of diffusive movements that do not require an intact cytoskeletal structure. These findings are consistent with total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) analysis on HIV-1 RNA that showed viral RNA as being highly mobile, thus suggesting that RNA would not be actively transported through the cytoplasm [10]. On the other hand, in the presence of a sufficient amount of Gag for virion assembly, data from the team of Hu showed that the cytoplasmic mobility of HIV-1 RNA would be similar to the mobility observed for gRNAs alone. In an apparent contrast, several other studies observed that gRNA reaches the PM in association with low-order multimers of Gag precursor [11,25,26]. However, these data are not necessary incompatible with each other since, considering the slower diffusion of the gRNA compared to Gag (see session 7), low-order cytolytic oligomers of Gag co-trafficking in association with gRNA could indeed have a minimal impact on viral RNA mobility [14,26].

A hallmark of retroviruses is that gRNAs are packaged as dimers, however at what point following RNA synthesis, or where dimerization occurs is still rather unclear. In vitro assays also showed that HIV-1 RNA fragments can heterodimerize with spliced viral RNAs only when the two RNAs are synthesized simultaneously [120]. These findings suggested that HIV-1 RNA dimerization could occur in the nucleus during transcription, although considering more recent results, this possibility seems unlikely, at least for HIV-1. Indeed, Mougel used a multicolor HIV-1 RNA labelling strategy coupled to single-molecule microscopy technologies to uncover dimerization mechanisms in the three-dimensionality of the cell [23]. This extensive analysis combined several fluorescence techniques, including fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), TIRF, 3D-super-resolution structured illumination microscopy, and FFS methods, as fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy (FCCS) aimed at monitoring the spatial RNA-RNA association in living cells and the dynamics of these complexes. To detect HIV-1 unspliced gRNA molecules in two colors, the 5′-end of the lacZ gene or the 24 repeats of the bacteriophage MS2 stem-loop were introduced within the pol gene, and these findings indicated that the dimerization of HIV-1 genome likely initiates in the cytosol [23]. In line with this idea, Moore et al. showed that HIV-1 RNA molecules destined for co-packaging into the same virion select each other mostly within the cytoplasm subsequently to nuclear exit [121]. On the other hand, both the teams of Mougel and Hu observed that the frequency of dimers is enriched near the PM, and the enrichment would last ∼30 min [11,13,15]. These findings could be compatible with an alternative model where HIV-1 RNA dimerization would occur at the PM [12]. However, of note, the highly dynamic cytosol, compared to the more stable environment of PM, renders these estimations very complex. Moreover, in virions dimers, frequencies were increased by a factor of four to five. Therefore, overall, these considerations seem to indicate that HIV-1 RNA dimers would be initially formed in the cytosol to then be stabilized at viral assembly sites.

Conversely, for other retroviruses such as MLV and RSV, gRNA dimerization was proven to occur in the nucleus. Indeed, MLV-spliced viral RNAs were observed to efficiently heterodimerize with the gRNA, and this suggested that MLV RNA dimerization would be coupled to transcription and splicing processes [122,123]. In addition, RSV RNA dimers were recently visualized in cultured quail fibroblasts using single molecule RNA imaging approaches. Subcellular localization analysis revealed that heterodimers are present in the nucleus, in the cytoplasm, and at the PM, indicating that genome dimers can form in the nucleus [124]. Interestingly, mutations of RNA elements promoting gRNA dimerization affect the intracellular trafficking of the viral genome, and result in an aberrant accumulation of gRNA either in the nucleus or in the cytoplasm [125,126].

Another relevant question is whether gRNA dimerization is initiated before or upon gRNA recognition by the Gag precursor. The analysis by Mougel and co-workers indicated that the NC domain in Gag would lead to the recruitment of gRNA dimers to subsequently traffic them to the assembly sites at PM [23]. Previous in vitro data showed that SL1 is the crucial element for the specific interaction with Gag, and gRNA dimerization would positively influence Gag binding, since an RNA fragment carrying mutations in the DIS palindromic sequence was fixed by the protein with a low affinity, compared to an RNA fragment corresponding to the native sequence [27,127]. It is thus possible that Gag selects a preformed dimeric gRNA from the bulk of the cellular and viral RNAs, and the interaction between the NC domain and the gRNA promotes dimer stabilization. This idea is also in agreement with several previous observations reporting HIV-1 Gag/NC chaperone activity on gRNA dimerization (reviewed in [128,129,130]), and the notion that gRNA dimers are preformed prior to encapsidation [12,23,121,131,132].

6. Where Is the gRNA Recruited?

The driving force for the encapsidation of gRNA mainly resides in Gag-gRNA interactions, and the specific selection of retroviral gRNA from a cytoplasmic pool of RNAs is regulated by specific RNA conformations which are supposed to expose the RNA high affinity binding sites to the NC domain within the Gag protein [27,91,127]. Some basic questions on retroviral mechanisms leading to gRNA packaging are how, when, and where the genome is recruited for packaging. In the HIV-1 context, two possibilities were explored, and accordingly Gag could recruit the gRNA in the cytoplasm, and in this case the ribonucleoprotein complex would traffic to the PM [21], or alternatively, RNA and Gag could independently reach the PM and the capture of the genome would occur at those sites [12]. Hu and coworkers demonstrated that the host cell machinery driving the transport of HIV-1 RNA out of the nucleus influences RNAs packaging into virions, as RNAs transported using the CRM-1 pathway do not co-package efficiently with RNAs transported by the NXF1 pathway, although Gag can package RNAs from both the two export pathways [121]. Moreover, in the cytoplasm, Chen et al. observed that both translating and non-translating viral RNAs exhibit dynamic movement and can reach the PM, even though Gag would selectively package non-translating RNA [133]. This single-molecule tracking analysis thus supported a model in which individual RNA molecules carry out only one function at a time.

Poeschla et al. used MS2 phage coat protein labelling to track spatial dynamics of primate and non-primate lentiviral genomic RNAs in live cells [114]. Indirect immunofluorescence and live-cell imaging thus revealed that both the lentiviral HIV-1 and FIV gRNAs traffic into the cytoplasm, and this process is Rev-dependent. Likewise, both lentiviral gRNAs were seen at the PM if and only if Gag was present and Psi was intact. However, FIV Gag and gRNA accumulated at the nuclear envelope contrary to HIV-1 Gag, and this marked the main difference between these two lentiviruses. Overall, this imaging analysis suggested that FIV Gag-genomic RNA interactions could initiate at the nuclear pore, and accordingly Gag would escort the genome during its entire cytoplasmic journey to the assembly sites at PM. On the other hand, observations from the group of Bieniasz proposed a model in which a small number of HIV-1 Gag molecules select viral RNAs in the cytoplasm, and once that the Gag-gRNA complex is anchored to the PM, further accumulation of Gag would lead to the subsequent assembly of the complete virion [10], a view in a good agreement with findings of other groups [21,23]. Therefore, Gag-membrane binding, Gag-RNA and Gag-Gag interactions provide similar scaffolding functions in the achievement of the viral particle assembly, and in line with this idea Carlson et al., using artificial membranes, observed by confocal microscopy that the formation of the Gag lattice and the packaging gRNA into new virus particles are linked processes [85].

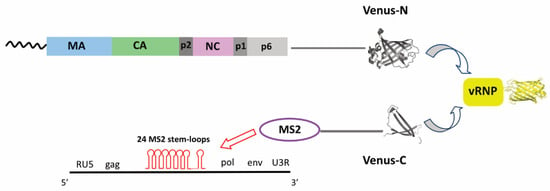

Several retroviral Gag proteins (for a review see [134]) as RSV Gag [135,136,137], MLV Gag [138], Foamy viruses Gag [139], MMTV Gag [140] and MPMV Gag [8] were found in the nucleus, and they are thought to interact with gRNA in this more confined space. In MLV the nuclear export of viral genome is mediated by Gag and occurs on endosomal vesicles [125]. In this retroviral context, Psi stem-loops are supposed to be involved in genome nuclear export and in endosomal transport, suggesting that RNA dimerization is linked to vesicular transport, which is consistent with the proposed requirement for Gag binding [125]. Furthermore, simple retroviruses lack accessory proteins (as for example the HIV-1 Rev that mediates the export of the unspliced gRNA from the nucleus [141]), and therefore, in RSV, Gag displays two nuclear localization signals (NLS) (one involving the importin-α/β pathway, and the other one the transportin SR and the importin-11 [142]) that allow the nuclear export of the unspliced genome. RSV Gag nuclear shuttling was extensively studied (for a review see [143]), and several studies demonstrated that Gag-gRNA interactions promote RSV Gag multimerization [50,80,136,137,144]. In turn, RSV Gag oligomerization produces a conformational change in Gag leading to the exposition of its nuclear export signal (NES), which can then interact with the nuclear export receptor CRM1. This leads the Gag-gRNA complex to cross the nuclear envelope and to be trafficked to the PM for packaging [136,137,145,146]. More recently, the group of Parent visualized Gag-gRNA interactions in the nuclei of infected QT6 quail fibroblast cells [147] by biomolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays where the two non-fluorescent halves of Venus protein were fused to MS2 and to Gag (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

In BiFC assays, the two halves of Venus fluorescent protein are fused to two interacting proteins of interest, as for example Gag and MS2 proteins [147]. One of the most widely used strategies to monitor gRNA trafficking in cells consists in the insertion of 24 stem-loop sequences in the target RNA which are then recognized with high affinity and specificity by the bacteriophage MS2 coat protein. While the two halves of Venus protein are non-fluorescent, the interaction of the partners tethers the fused fluorescent fragments in proximity, which facilitates the restoration of Venus fluorescence. BiFC is a reliable and sensitive approach that also revealed molecular interactions in other viral contexts, such as the Herpes virus [148].

This nuclear interaction, however, leaves many unanswered questions including the possible role of RSV Gag in splicing, in genome expression, or also in chromatin modifications. Interestingly, Parent et al. recently visualized HIV-1 Gag and unspliced viral RNA in discrete foci of Hela cells. At those sites, Gag was found to accumulate at stalled transcription sites. Also, in CD4+ T infected cells treated to stimulate NF-κB mediated transcription, HIV-1 Gag was found to localize at transcriptional burst sites. Altogether these findings open the possibility that also HIV-1 Gag can be found in the nuclei bound to unspliced viral transcripts [149]. Also, HIV-1 Gag was observed to contain an NLS and an NES within the MA, and mutation of the NES would interfere with gRNA packaging [150], but this result has not been further explored. Finally, previous controversial results on the presence of HIV-1 Gag-gRNA complexes outside of the nuclear envelope [114,151] indicate that whether HIV Gag gRNA packaging involves nuclear events has not been fully resolved yet. Therefore, even if it is possible that that formation of HIV-1 vRNP between Gag and gRNA can occur in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm, further studies will be necessary to definitively elucidate this point. One of the limiting factors in these observations resides in the detection limit of fluorescent microscopy, which could be not sensitive enough to visualize small nuclear Gag foci. In future studies, the use of super-resolution imaging techniques in living cells would then be crucial to improve the visualization of vRNPs biogenesis and their trafficking to the PM.

8. Molecular Mechanisms Occurring at the PM

One of the most important challenges to better understand retroviral assembly is to obtain a clear picture of the spatial and temporal organization of the viral and cellular components interacting at the assembly sites. Indeed, opting for an optimal imaging modality to analyse protein-RNA interactions is not simple, and methods providing good spatial resolution are usually less performant in temporal resolution, which is in turn an essential feature for investigating rapid time scales of viral processes. In the past, in addition to subcellular fractionation, and immunofluorescence, electron microscopy (EM) showed that HIV-1 assembly takes place at the PM [76] (Table 1). However, even if this method can resolve finer spatial details compared to the classical light microscopy, cells are fixed, and temporal resolution is completely lost. For this reason, EM was coupled to other methods, such as atomic force microscopy (AFM) which previously allowed to monitor retroviral budding events [161]. This technique is indeed suitable to measure the distortion of the membrane, although with a technically limited temporal resolution of several minutes per frame (Table 1). Temporal information on Gag-gRNA interactions at the PM was also obtained by using photoconvertible fluorescent proteins Eos via an RNA-binding protein that specifically recognizes stem-loops engineered into the HIV-1 viral genome to distinguish between existing and newly arriving viral RNAs at the PM [15]. Accordingly, photoconverted Eos proteins allowed the detection of RNAs at the PM by red signals, while the RNAs that reached the PM later were unmodified and carried green signals. Sardo et al. could thus observe that in the absence of HIV-1 Gag, most of the gRNAs remain transiently at the PM, while in the presence of Gag, the permanence of gRNA at the assembly sites was significantly increased as gRNAs could be still detected after 30 min [15]. In agreement with these findings, Jouvenet et al. observed highly dynamic HIV-1 RNA molecules in the cytoplasm that move rapidly in the proximity of the PM, thus remaining visible in the observation field for no longer than a few seconds. On the other hand, when Gag is co-expressed, a fraction of the RNA molecules is found to dock at the membrane, displaying slow and lateral drift (∼ 0.01 μm/s) [10]. Therefore, the duration of HIV-1 RNA retention at the PM depends on Gag expression, indicating that at the assembly sites gRNA is associated to Gag.

The photoconvertible proteins Eos were also used by Jouvenet et al. to monitor Gag recruitment at the assembly sites. These findings demonstrated that Gag proteins reach the assembly sites mainly from the cytosol, rather than from lateral diffusion on membranes [13]. The assembly of individual virions was also observed in real-time. As such, the gradual recruitment of Gag fused GFP at budding sites was observable as the fluorescence intensity initially followed a saturating exponential, while the end of this phase was marked by a plateau of the fluorescence intensity [11]. As the signal produced by Gag increased, the lateral movements of gRNA molecules were observed to decrease, indicating that Gag accumulation promotes gRNA anchoring to the PM [159]. At those sites remarkably about 75% of the assembly events occur on HIV-1 Gag-gRNA complexes, which is in line with the notion that viral RNA plays a scaffolding role at the assembly sites [10]. Of note, the recruitment of the viral RNA is reversible (whenever the assembly of Gag is disrupted), even though the time observed for viral RNA dissociation from a multimerization defective Gag is greater that the time necessary for the accumulation of Gag at the assembly sites [10].

However, during the assembly process, Gag proteins are constituted by a mixed population of molecules at potentially different stages of assembly, and thus it can be somehow difficult to determine whether a fluorescent signal is produced by assembling Gag proteins or by virions. Moreover, the situation can be also complicated by the fact that retroviral assembly is a rare event that emits a fluorescent signal in a large background. Therefore, the combination of different methods is necessary to obtain a more precise picture of the assembly events. As such, FRAP is a suitable method to analyze cellular mobility of HIV-1 Gag and provides accurate information on immobile fractions [77] (Table 1). Indeed, this method allows the distinguishing between particles that continuously recruit Gag molecules (which displayed increasing fluorescence during the prebleach period, and that recover a signal after bleaching), from particles for which the recruitment was already completed (whose intensity was found to be high and stable during the prebleach period, and that do not recover after bleaching) [11]. Of note, Gag cannot be directly detected in its first association with PM, and on average, ∼ 4.5 min from the appearance of the viral RNA at the PM, are necessary to start observing the signal of Gag proteins [11].

One of the most vastly used methods to analyze the genesis of the individual virions at PM was TIRF [10,11,13,159]. This method indeed displays a sufficient signal-to- noise ratio to allow the quantification of the individual assembling particles, since the illuminated volume corresponds to a shallow region between the glass and the cell, and fluorophores in proximity (≈<70–100 nm) of the coverslip are then excited (Table 1). However, TIRF is also sensitive to the axial position of the fluorescent molecules, and fluctuations of the fluorescence intensity due to movement of the PM could cause difficulties in the measure of the assembly complexes. For this reason, TIRF microscopy was complemented with wide-field observation [13,162], and it was thus observed that the assembly of HIV-1 Gag shell takes ∼200 s [13]. Altogether, these observations are consistent with a model where a small number of Gag molecules (i.e., below the detection limit) interacts with gRNA that is thus immobilized at the PM during the early events of particle assembly. These vRNP complexes therefore constitute the nucleation sites for the recruitment of further Gag molecules [10]. At this stage, Gag conformational changes convert the initial small oligomers into assembly-competent ones, and retroviral particle assembly is achieved through a set of larger intermediates. The time-lapse between the first recruitment of gRNA to the PM (by a small number of HIV-1 Gag) and the completion of the viral particle at the assembly sites (which corresponds to the termination of Gag accumulation) was estimated between to be between six and 27 min by Jouvenet et al. [159]. This estimation is in agreement with other observations indicating that signals reporting HIV-1 Gag accumulation at the PM take five to 30 min to reach their maximal intensity [13,163].

Finally, neither mutations of the late domain motifs altered the assembly rates [13], nor did protein labelling influence the time necessary for Gag accumulation on the PM [11]. Conversely, in good agreement with previous biochemical data [26], Gag proteins defective in the CA domain failed to retain viral RNA, which tended to dissociate from the membrane after about 8 min [159].

Similarly, to what was observed for HIV-1, TIRF microscopy on live cells showed that FIV gRNA, in the absence of Gag, moves in and out of the proximity of the PM, remaining therefore at those sites for no longer than a few seconds [114,162]. Conversely, when Gag is expressed, the genome accumulates at the PM. HIV-1 and FIV genomes co-expressed with the corresponding Gag mutants impaired in PM binding were not detectable at the PM, which provides additional evidence that Gag is responsible for anchoring the genomes at the assembly sites [10,114,164]. Those specific locations where HIV-1 assembly is initiated are enriched by lipid rafts, cholesterol and tetraspannines (reviewed in [36,165]). However, retroviruses developed multiple ways to assemble, and thus many membrane platforms give rise to multiple consecutive budding events of RSV differently from the mostly unique sites observed for MLV and HIV-1 [70,161]. TIRF analysis on individual assembling VLPs from the time of nucleation to the recruitment of VPS4, an ESCRT component which marks the final stage of VLP assembly, showed that VLPs can be paused (from 2 to 20 min) at various stages [163]. The cellular ESCRT machinery indeed corresponds to the molecular signature necessary for the separation of nascent VLPs from the host cell (reviewed in [166,167,168]). Finally, imaging HIV-1 particles generated with a Gag fused to pHluorin, (a GFP variant whose fluorescence is diminished at acidic pH) allowed for the observation that it takes about 30 min for virions to disconnect from the cytosol [11], which is in rather good agreement with data from Lamb et al. that showed that the release occurred with an average delay of about 25 min after the completion of the Gag assembly [13].

9. Concluding Remarks

In these last decades, the development of bioimaging tools allowed the visualization of retroviral genesis and led to a deeper quantitative analysis of the molecular mechanisms regulating gRNA packaging in living cells. As a result, instead of the differences among retroviruses, the recruitment of gRNA was overall observed to be driven by a small number of Gag molecules at different cellular sites (as cytoplasm or nucleus) depending on the retrovirus. Similarly, these techniques allowed for the monitoring of the time-dependent intracellular localization of viral components and the order of the events occurring at the viral budding sites. Indeed, the elaboration of these approaches addressed many important questions, although studies to this point have been limited to a few retroviruses, and there remain several open questions in the biology of retroviral assembly. Also, a number of cellular factors were observed to interact with HIV-1 Gag (e.g., APOBEC3G, Nedd4-1, Tsg101, Alix, ABCE1, Actin; for a review see [169]), and to be specifically encapsidated into the viral particles (e.g., Staufen, RNA 7SL) [170,171,172,173]. However, despite the plethora of studies on this topic, the actual implication of those molecules in HIV-1 assembly and replication still needs to be confirmed. With further technological and conceptual development, advancements in our understanding of the mechanisms leading to retroviral gRNA packaging and to their assembly awaits. In this vein the development of super-resolution techniques providing a resolution close to the molecular scale such as stimulated emission depletion (STED) [174], stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM) [175] and photo-activated localization microscopy (PALM) [176] would be determinant. These methods, that allow for penetration beyond the diffraction limit of conventional optical techniques and that achieve resolutions of about 20 nm in the focal plane (for reviews see [177,178]), would thus contribute to the clarity of our picture of the last phases of the retroviral life cycle and provide the experimental basis necessary to interfere with viral replication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agence Nationale de Recherche sur le SIDA et les hépatites virales (ANRS, 2020-1), and IdEx 2020-Attractivité (Initiative d’Excellence, Université de Strasbourg, France).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflict of interest declared.

References

- Mailler, E.; Bernacchi, S.; Marquet, R.; Paillart, J.-C.; Vivet-Boudou, V.; Smyth, R. The Life-Cycle of the HIV-1 Gag–RNA Complex. Viruses 2016, 8, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rein, A.; Datta, S.A.K.; Jones, C.P.; Musier-Forsyth, K. Diverse Interactions of Retroviral Gag Proteins with RNAs. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2011, S0968000411000545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, E.D.; Musier-Forsyth, K. Retroviral Gag Protein-RNA Interactions: Implications for Specific Genomic RNA Packaging and Virion Assembly. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 86, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, N.; Marquet, R.; Paillart, J.-C.; Bernacchi, S. Retroviral RNA Dimerization: From Structure to Functions. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, A.M.L. HIV RNA Packaging and Lentivirus-Based Vectors. In Advances in Pharmacology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 48, pp. 1–28. ISBN 978-0-12-032949-6. [Google Scholar]

- Comas-Garcia, M.; Davis, S.; Rein, A. On the Selective Packaging of Genomic RNA by HIV-1. Viruses 2016, 8, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, V.; Summers, M.F. How Retroviruses Select Their Genomes. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, T.A.; Schmidt, R.D.; Lew, K.A. Mason–Pfizer Monkey Virus (MPMV) Constitutive Transport Element (CTE) Functions in a Position-Dependent Manner. Virology 1997, 236, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouvenet, N.; Neil, S.J.D.; Bess, C.; Johnson, M.C.; Virgen, C.A.; Simon, S.M.; Bieniasz, P.D. Plasma Membrane Is the Site of Productive HIV-1 Particle Assembly. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4, e435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouvenet, N.; Simon, S.M.; Bieniasz, P.D. Imaging the Interaction of HIV-1 Genomes and Gag during Assembly of Individual Viral Particles. PNAS 2009, 106, 19114–19119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouvenet, N.; Bieniasz, P.D.; Simon, S.M. Imaging the Biogenesis of Individual HIV-1 Virions in Live Cells. Nature 2008, 454, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Rahman, S.A.; Nikolaitchik, O.A.; Grunwald, D.; Sardo, L.; Burdick, R.C.; Plisov, S.; Liang, E.; Tai, S.; Pathak, V.K.; et al. HIV-1 RNA Genome Dimerizes on the Plasma Membrane in the Presence of Gag Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E201–E208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanchenko, S.; Godinez, W.J.; Lampe, M.; Kräusslich, H.-G.; Eils, R.; Rohr, K.; Bräuchle, C.; Müller, B.; Lamb, D.C. Dynamics of HIV-1 Assembly and Release. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, J.; Baumgärtel, V.; Schrimpf, W.; Ivanchenko, S.; Digman, M.A.; Gratton, E.; Kräusslich, H.-G.; Müller, B.; Lamb, D.C. Live-Cell Observation of Cytosolic HIV-1 Assembly Onset Reveals RNA-Interacting Gag Oligomers. J. Cell Biol. 2015, 210, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sardo, L.; Hatch, S.C.; Chen, J.; Nikolaitchik, O.; Burdick, R.C.; Chen, D.; Westlake, C.J.; Lockett, S.; Pathak, V.K.; Hu, W.-S. Dynamics of HIV-1 RNA Near the Plasma Membrane during Virus Assembly. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 10832–10840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubner, W.; Chen, P.; Portillo, A.D.; Liu, Y.; Gordon, R.E.; Chen, B.K. Sequence of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) Gag Localization and Oligomerization Monitored with Live Confocal Imaging of a Replication-Competent, Fluorescently Tagged HIV-1. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 12596–12607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, D.R.; Ma, Y.M.; Vogt, V.M.; Webb, W.W. Direct Measurement of Gag–Gag Interaction during Retrovirus Assembly with FRET and Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy. J. Cell. Biol. 2003, 162, 1233–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arhel, N.; Genovesio, A.; Kim, K.-A.; Miko, S.; Perret, E.; Olivo-Marin, J.-C.; Shorte, S.; Charneau, P. Quantitative Four-Dimensional Tracking of Cytoplasmic and Nuclear HIV-1 Complexes. Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D. The inside Track on HIV. Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 782–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudner, L.; Nydegger, S.; Coren, L.V.; Nagashima, K.; Thali, M.; Ott, D.E. Dynamic Fluorescent Imaging of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Gag in Live Cells by Biarsenical Labeling. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 4055–4065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutant, E.; Bonzi, J.; Anton, H.; Nasim, M.B.; Cathagne, R.; Réal, E.; Dujardin, D.; Carl, P.; Didier, P.; Paillart, J.-C.; et al. Zinc Fingers in HIV-1 Gag Precursor Are Not Equivalent for GRNA Recruitment at the Plasma Membrane. Biophys. J. 2020, 119, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Grunwald, D.; Sardo, L.; Galli, A.; Plisov, S.; Nikolaitchik, O.A.; Chen, D.; Lockett, S.; Larson, D.R.; Pathak, V.K.; et al. Cytoplasmic HIV-1 RNA Is Mainly Transported by Diffusion in the Presence or Absence of Gag Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E5205–E5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, M.; Clerté, C.; Chamontin, C.; Basyuk, E.; Lainé, S.; Hottin, J.; Bertrand, E.; Margeat, E.; Mougel, M. Imaging HIV-1 RNA Dimerization in Cells by Multicolor Super-Resolution and Fluctuation Microscopies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 7922–7934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.-A.; Briggs, J.A.G.; Glass, B.; Riches, J.D.; Simon, M.N.; Johnson, M.C.; Müller, B.; Grünewald, K.; Kräusslich, H.-G. Three-Dimensional Analysis of Budding Sites and Released Virus Suggests a Revised Model for HIV-1 Morphogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 4, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutluay, S.B.; Zang, T.; Blanco-Melo, D.; Powell, C.; Jannain, D.; Errando, M.; Bieniasz, P.D. Global Changes in the RNA Binding Specificity of HIV-1 Gag Regulate Virion Genesis. Cell 2014, 159, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutluay, S.B.; Bieniasz, P.D. Analysis of the Initiating Events in HIV-1 Particle Assembly and Genome Packaging. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernacchi, S.; Abd El-Wahab, E.W.; Dubois, N.; Hijnen, M.; Smyth, R.P.; Mak, J.; Marquet, R.; Paillart, J.-C. HIV-1 Pr55 Gag Binds Genomic and Spliced RNAs with Different Affinity and Stoichiometry. RNA Biol. 2017, 14, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, J.A.G.; Simon, M.N.; Gross, I.; Kräusslich, H.-G.; Fuller, S.D.; Vogt, V.M.; Johnson, M.C. The Stoichiometry of Gag Protein in HIV-1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004, 11, 672–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, E.O. HIV-1 Assembly, Release and Maturation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 484–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussienne, C.; Marquet, R.; Paillart, J.-C.; Bernacchi, S. Post-Translational Modifications of Retroviral HIV-1 Gag Precursors: An Overview of Their Biological Role. IJMS 2021, 22, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Resh, M.D. Differential Membrane Binding of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Matrix Protein. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 8540–8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillart, J.-C.; Göttlinger, H.G. Opposing Effects of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Matrix Mutations Support a Myristyl Switch Model of Gag Membrane Targeting. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 2604–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Loeliger, E.; Luncsford, P.; Kinde, I.; Beckett, D.; Summers, M.F. Entropic Switch Regulates Myristate Exposure in the HIV-1 Matrix Protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandefur, S.; Smith, R.M.; Varthakavi, V.; Spearman, P. Mapping and Characterization of the N-Terminal I Domain of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Pr55 Gag. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 7238–7249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ono, A.; Freed, E.O. Cell-Type-Dependent Targeting of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Assembly to the Plasma Membrane and the Multivesicular Body. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 1552–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukkapalli, V.; Ono, A. Molecular Determinants That Regulate Plasma Membrane Association of HIV-1 Gag. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 512–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukkapalli, V.; Hogue, I.B.; Boyko, V.; Hu, W.-S.; Ono, A. Interaction between the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Gag Matrix Domain and Phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-Bisphosphate Is Essential for Efficient Gag Membrane Binding. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 2405–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, J.S.; Miller, J.; Tai, J.; Kim, A.; Ghanam, R.H.; Summers, M.F. Structural Basis for Targeting HIV-1 Gag Proteins to the Plasma Membrane for Virus Assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11364–11369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.P.; Datta, S.A.K.; Rein, A.; Rouzina, I.; Musier-Forsyth, K. Matrix Domain Modulates HIV-1 Gag’s Nucleic Acid Chaperone Activity via Inositol Phosphate Binding. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 1594–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, G.C.; Duchon, A.; Inlora, J.; Olson, E.D.; Musier-Forsyth, K.; Ono, A. Inhibition of HIV-1 Gag–Membrane Interactions by Specific RNAs. RNA 2017, 23, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukkapalli, V.; Oh, S.J.; Ono, A. Opposing Mechanisms Involving RNA and Lipids Regulate HIV-1 Gag Membrane Binding through the Highly Basic Region of the Matrix Domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 1600–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniasz, P.; Telesnitsky, A. Multiple, Switchable Protein:RNA Interactions Regulate Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Assembly. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2018, 5, 165–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, J.B.; Nath, A.; Färber, M.; Datta, S.A.K.; Rein, A.; Rhoades, E.; Mothes, W. A Conformational Transition Observed in Single HIV-1 Gag Molecules during In Vitro Assembly of Virus-Like Particles. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 3577–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obr, M.; Ricana, C.L.; Nikulin, N.; Feathers, J.-P.R.; Klanschnig, M.; Thader, A.; Johnson, M.C.; Vogt, V.M.; Schur, F.K.M.; Dick, R.A. Structure of the Mature Rous Sarcoma Virus Lattice Reveals a Role for IP6 in the Formation of the Capsid Hexamer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schur, F.K.M.; Dick, R.A.; Hagen, W.J.H.; Vogt, V.M.; Briggs, J.A.G. The Structure of Immature Virus-Like Rous Sarcoma Virus Gag Particles Reveals a Structural Role for the P10 Domain in Assembly. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 10294–10302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamble, T.R.; Yoo, S.; Vajdos, F.F.; von Schwedler, U.K.; Worthylake, D.K.; Wang, H.; McCutcheon, J.P.; Sundquist, W.I.; Hill, C.P. Structure of the Carboxyl-Terminal Dimerization Domain of the HIV-1 Capsid Protein. Science 1997, 278, 849–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schwedler, U.K.; Stray, K.M.; Garrus, J.E.; Sundquist, W.I. Functional Surfaces of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Capsid Protein. JVI 2003, 77, 5439–5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfman, T.; Bukovsky, A.; Ohagen, A.; Höglund, S.; Göttlinger, H.G. Functional Domains of the Capsid Protein of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 8180–8187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Accola, M.A.; Strack, B.; Göttlinger, H.G. Efficient Particle Production by Minimal Gag Constructs Which Retain the Carboxy-Terminal Domain of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Capsid-P2 and a Late Assembly Domain. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 5395–5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.M.; Vogt, V.M. Rous Sarcoma Virus Gag Protein-Oligonucleotide Interaction Suggests a Critical Role for Protein Dimer Formation in Assembly. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 5452–5462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.J. Complex Interactions of HIV-1 Nucleocapsid Protein with Oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houzet, L.; Morichaud, Z.; Didierlaurent, L.; Muriaux, D.; Darlix, J.-L.; Mougel, M. Nucleocapsid Mutations Turn HIV-1 into a DNA-Containing Virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 2311–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Didierlaurent, L.; Houzet, L.; Morichaud, Z.; Darlix, J.-L.; Mougel, M. The Conserved N-Terminal Basic Residues and Zinc-Finger Motifs of HIV-1 Nucleocapsid Restrict the Viral CDNA Synthesis during Virus Formation and Maturation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 4745–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Grigsby, I.F.; Gorelick, R.J.; Mansky, L.M.; Musier-Forsyth, K. Retrovirus-Specific Differences in Matrix and Nucleocapsid Protein-Nucleic Acid Interactions: Implications for Genomic RNA Packaging. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dick, R.A.; Datta, S.A.K.; Nanda, H.; Fang, X.; Wen, Y.; Barros, M.; Wang, Y.-X.; Rein, A.; Vogt, V.M. Hydrodynamic and Membrane Binding Properties of Purified Rous Sarcoma Virus Gag Protein. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 10371–10382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zábranský, A.; Hoboth, P.; Hadravová, R.; Štokrová, J.; Sakalian, M.; Pichová, I. The Noncanonical Gag Domains P8 and n Are Critical for Assembly and Release of Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 11555–11559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdusetir Cerfoglio, J.C.; González, S.A.; Affranchino, J.L. Structural Elements in the Gag Polyprotein of Feline Immunodeficiency Virus Involved in Gag Self-Association and Assembly. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 2050–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, L.J.; Bennett, R.P.; Craven, R.C.; Nelle, T.D.; Krishna, N.K.; Bowzard, J.B.; Wilson, C.B.; Puffer, B.A.; Montelaro, R.C.; Wills, J.W. Positionally Independent and Exchangeable Late Budding Functions of the Rous Sarcoma Virus and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Gag Proteins. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 5455–5460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, J.; Hunter, E. A Proline-Rich Motif (PPPY) in the Gag Polyprotein of Mason-Pfizer Monkey Virus Plays a Maturation-Independent Role in Virion Release. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 4095–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, L.; Paillart, J.-C.; Bernacchi, S. Importance of Viral Late Domains in Budding and Release of Enveloped RNA Viruses. Viruses 2021, 13, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, L.; Sun, D.; Ning, J.; Liu, J.; Kotecha, A.; Olek, M.; Frosio, T.; Fu, X.; Himes, B.A.; Kleinpeter, A.B.; et al. CryoET Structures of Immature HIV Gag Reveal Six-Helix Bundle. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiegers, K.; Rutter, G.; Kottler, H.; Tessmer, U.; Hohenberg, H.; Kräusslich, H.-G. Sequential Steps in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Particle Maturation Revealed by Alterations of Individual Gag Polyprotein Cleavage Sites. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 2846–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, B.B.; Russell, R.S.; Turner, D.; Liang, C. The T12I Mutation within the SP1 Region of Gag Restricts Packaging of Spliced Viral RNA into Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 with Mutated RNA Packaging Signals and Mutated Nucleocapsid Sequence. Virology 2006, 344, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, R.S.; Roldan, A.; Detorio, M.; Hu, J.; Wainberg, M.A.; Liang, C. Effects of a Single Amino Acid Substitution within Thep2 Region of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 on Packagingof Spliced ViralRNA. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 12986–12995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wanaguru, M.; Barry, D.J.; Benton, D.J.; O’Reilly, N.J.; Bishop, K.N. Murine Leukemia Virus P12 Tethers the Capsid-Containing Pre-Integration Complex to Chromatin by Binding Directly to Host Nucleosomes in Mitosis. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanwar, H.S.; Khoo, K.K.; Garvey, M.; Waddington, L.; Leis, A.; Hijnen, M.; Velkov, T.; Dumsday, G.J.; McKinstry, W.J.; Mak, J. The Thermodynamics of Pr55Gag-RNA Interaction Regulate the Assembly of HIV. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, N.; Khoo, K.K.; Ghossein, S.; Seissler, T.; Wolff, P.; McKinstry, W.J.; Mak, J.; Paillart, J.-C.; Marquet, R.; Bernacchi, S. The C-Terminal P6 Domain of the HIV-1 Pr55 Gag Precursor Is Required for Specific Binding to the Genomic RNA. RNA Biol. 2018, 15, 923–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, B.; Daecke, J.; Fackler, O.T.; Dittmar, M.T.; Zentgraf, H.; Kräusslich, H.-G. Construction and Characterization of a Fluorescently Labeled Infectious Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Derivative. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 10803–10813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornillos, O.; Higginson, D.S.; Stray, K.M.; Fisher, R.D.; Garrus, J.E.; Payne, M.; He, G.-P.; Wang, H.E.; Morham, S.G.; Sundquist, W.I. HIV Gag Mimics the Tsg101-Recruiting Activity of the Human Hrs Protein. J. Cell Biol. 2003, 162, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, D.R.; Johnson, M.C.; Webb, W.W.; Vogt, V.M. Visualization of Retrovirus Budding with Correlated Light and Electron Microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15453–15458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, R. Photoconvertible Fluorescent Proteins and the Role of Dynamics in Protein Evolution. IJMS 2017, 18, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaner, N.C.; Steinbach, P.A.; Tsien, R.Y. A Guide to Choosing Fluorescent Proteins. Nat. Methods 2005, 2, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiedenmann, J.; Oswald, F.; Nienhaus, G.U. Fluorescent Proteins for Live Cell Imaging: Opportunities, Limitations, and Challenges. IUBMB Life 2009, 61, 1029–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, B.A.; Adams, S.R.; Tsien, R.Y. Specific Covalent Labeling of Recombinant Protein Molecules Inside Live Cells. Science 1998, 281, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-M.; Yu, X.-F. Identification and Characterization of Virus Assembly Intermediate Complexes in HIV-1-Infected CD4+T Cells. Virology 1998, 243, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nermut, M.V.; Fassati, A. Structural Analyses of Purified Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Intracellular Reverse Transcription Complexes. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 8196–8206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gomez, C.Y.; Hope, T.J. Mobility of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Pr55 Gag in Living Cells. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 8796–8806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogue, I.B.; Hoppe, A.; Ono, A. Quantitative Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer Microscopy Analysis of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Gag-Gag Interaction: Relative Contributions of the CA and NC Domains and Membrane Binding. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 7322–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfadhli, A.; Dhenub, T.C.; Still, A.; Barklis, E. Analysis of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Gag Dimerization-Induced Assembly. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 14498–14506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.C.; Scobie, H.M.; Ma, Y.M.; Vogt, V.M. Nucleic Acid-Independent Retrovirus Assembly Can Be Driven by Dimerization. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 11177–11185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.M.; Vogt, V.M. Nucleic Acid Binding-Induced Gag Dimerization in the Assembly of Rous Sarcoma Virus Particles In Vitro. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldan, A.; Russell, R.S.; Marchand, B.; Götte, M.; Liang, C.; Wainberg, M.A. In Vitro Identification and Characterization of an Early Complex Linking HIV-1 Genomic RNA Recognition and Pr55Gag Multimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 39886–39894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Roy, B.B.; Hu, J.; Roldan, A.; Wainberg, M.A.; Liang, C. The R362A Mutation at the C-Terminus of CA Inhibits Packaging of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 RNA. Virology 2005, 343, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, J.F.; Lever, A.M.L. Nonreciprocal Packaging of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 and Type 2 RNA: A Possible Role for the P2 Domain of Gag in RNA Encapsidation. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 5877–5885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.-A.; Bai, Y.; Keane, S.C.; Doudna, J.A.; Hurley, J.H. Reconstitution of Selective HIV-1 RNA Packaging in Vitro by Membrane-Bound Gag Assemblies. eLife 2016, 5, e14663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogarty, K.H.; Chen, Y.; Grigsby, I.F.; Macdonald, P.J.; Smith, E.M.; Johnson, J.L.; Rawson, J.M.; Mansky, L.M.; Mueller, J.D. Characterization of Cytoplasmic Gag-Gag Interactions by Dual-Color Z-Scan Fluorescence Fluctuation Spectroscopy. Biophys. J. 2011, 100, 1587–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, V.N.; Ali, L.M.; Prabhu, S.G.; Krishnan, A.; Chameettachal, A.; Pitchai, F.N.N.; Mustafa, F.; Rizvi, T.A. A Stretch of Unpaired Purines in the Leader Region of Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV) Genomic RNA Is Critical for Its Packaging into Virions. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 167293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, L.M.; Pitchai, F.N.N.; Vivet-Boudou, V.; Chameettachal, A.; Jabeen, A.; Pillai, V.N.; Mustafa, F.; Marquet, R.; Rizvi, T.A. Role of Purine-Rich Regions in Mason-Pfizer Monkey Virus (MPMV) Genomic RNA Packaging and Propagation. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 595410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaballah, S.A.; Aktar, S.J.; Ali, J.; Phillip, P.S.; Al Dhaheri, N.S.; Jabeen, A.; Rizvi, T.A. A G–C-Rich Palindromic Structural Motif and a Stretch of Single-Stranded Purines Are Required for Optimal Packaging of Mason–Pfizer Monkey Virus (MPMV) Genomic RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 401, 996–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houzet, L.; Paillart, J.C.; Smagulova, F.; Maurel, S.; Morichaud, Z.; Marquet, R.; Mougel, M. HIV Controls the Selective Packaging of Genomic, Spliced Viral and Cellular RNAs into Virions through Different Mechanisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 2695–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, R.P.; Despons, L.; Huili, G.; Bernacchi, S.; Hijnen, M.; Mak, J.; Jossinet, F.; Weixi, L.; Paillart, J.-C.; von Kleist, M.; et al. Mutational Interference Mapping Experiment (MIME) for Studying RNA Structure and Function. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tounekti, N.; Mougel, M.; Roy, C.; Marquet, R.; Darlix, J.-L.; Paoletti, J.; Ehresmann, B.; Ehresmann, C. Effect of Dimerization on the Conformation of the Encapsidation Psi Domain of Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 1992, 223, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougel, M.; Barklis, E. A Role for Two Hairpin Structures as a Core RNA Encapsidation Signal in Murine Leukemia Virus Virions. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 8061–8065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oroudjev, E.M.; Kang, P.C.E.; Kohlstaedt, L.A. An Additional Dimer Linkage Structure in Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus RNA 1 1Edited by D. E. Draper. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 291, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, H.; Parslow, T.G. Bipartite Signal for Genomic RNA Dimerization in Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3135–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Liu, S.; Kaddis Maldonado, R.; Rye-McCurdy, T.; Binkley, C.; Bah, A.; Chen, E.C.; Rice, B.L.; Parent, L.J.; Musier-Forsyth, K. Rous Sarcoma Virus Genomic RNA Dimerization Capability In Vitro Is Not a Prerequisite for Viral Infectivity. Viruses 2020, 12, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, A.; Gottlinger, H.; Haseltine, W.; Sodroski, J. Identification of a Sequence Required for Efficient Packaging of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 RNA into Virions. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 4085–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clever, J.; Sassetti, C.; Parslow, T.G. RNA Secondary Structure and Binding Sites for Gag Gene Products in the 5’ Packaging Signal of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 2101–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughrea, M.; Jetté, L.; Mak, J.; Kleiman, L.; Liang, C.; Wainberg, M.A. Mutations in the Kissing-Loop Hairpin of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Reduce Viral Infectivity as Well as Genomic RNA Packaging and Dimerization. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 3397–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennifar, E.; Walter, P.; Ehresmann, B.; Ehresmann, C.; Dumas, P. Crystal Structures of Coaxially Stacked Kissing Complexes of the HIV-1 RNA Dimerization Iniziatin Site. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2001, 8, 1064–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ennifar, E.; Carpentier, P.; Ferrer, J.L.; Walter, P.; Dumas, P. X-Ray-Induced Debromination of Nucleic Acids at the Br K Absorption Edge and Implications for MAD Phasing. Acta Cryst. D Biol. Cryst. 2002, 58, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skripkin, E.; Paillart, J.C.; Marquet, R.; Ehresmann, B.; Ehresmann, C. Identification of the Primary Site of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 RNA Dimerization in Vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 4945–4949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paillart, J.C.; Skripkin, E.; Ehresmann, B.; Ehresmann, C.; Marquet, R. A Loop-Loop “Kissing” Complex Is the Essential Part of the Dimer Linkage of Genomic HIV-1 RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 5572–5577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weixlbaumer, A. Determination of Thermodynamic Parameters for HIV DIS Type Loop-Loop Kissing Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 5126–5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chameettachal, A.; Vivet-Boudou, V.; Pitchai, F.N.N.; Pillai, V.N.; Ali, L.M.; Krishnan, A.; Bernacchi, S.; Mustafa, F.; Marquet, R.; Rizvi, T.A. A Purine Loop and the Primer Binding Site Are Critical for the Selective Encapsidation of Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus Genomic RNA by Pr77Gag. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 4668–4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muriaux, D.; Fossé, P.; Paoletti, J. A Kissing Complex Together with a Stable Dimer Is Involved in the HIV-1 Lai RNA Dimerization Process in Vitro. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 5075–5082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacchi, S.; Ennifar, E.; Tóth, K.; Walter, P.; Langowski, J.; Dumas, P. Mechanism of Hairpin-Duplex Conversion for the HIV-1 Dimerization Initiation Site. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 40112–40121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, J.G.; Guo, J.; Rouzina, I.; Musier-Forsyth, K. Nucleic Acid Chaperone Activity of HIV-1 Nucleocapsid Protein: Critical Role in Reverse Transcription and Molecular Mechanism. In Progress in Nucleic Acid Research and Molecular Biology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 80, pp. 217–286. ISBN 978-0-12-540080-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rist, M.J.; Marino, J.P. Mechanism of Nucleocapsid Protein Catalyzed Structural Isomerization of the Dimerization Initiation Site of HIV-1. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 14762–14770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigham, B.S.; Kitzrow, J.P.; Reyes, J.-P.C.; Musier-Forsyth, K.; Munro, J.B. Intrinsic Conformational Dynamics of the HIV-1 Genomic RNA 5′UTR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10372–10381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Heng, X.; Garyu, L.; Monti, S.; Garcia, E.L.; Kharytonchyk, S.; Dorjsuren, B.; Kulandaivel, G.; Jones, S.; Hiremath, A.; et al. NMR Detection of Structures in the HIV-1 5’-Leader RNA That Regulate Genome Packaging. Science 2011, 334, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Liu, Y.; Marchant, J.; Monti, S.; Seu, M.; Zaki, J.; Yang, A.L.; Bohn, J.; Ramakrishnan, V.; Singh, R.; et al. Conserved Determinants of Lentiviral Genome Dimerization. Retrovirology 2015, 12, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalloush, R.M.; Vivet-Boudou, V.; Ali, L.M.; Pillai, V.N.; Mustafa, F.; Marquet, R.; Rizvi, T.A. Stabilizing Role of Structural Elements within the 5´ Untranslated Region (UTR) and Gag Sequences in Mason-Pfizer Monkey Virus (MPMV) Genomic RNA Packaging. RNA Biol. 2019, 16, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemler, I.; Meehan, A.; Poeschla, E.M. Live-Cell Coimaging of the Genomic RNAs and Gag Proteins of Two Lentiviruses. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 6352–6366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pocock, G.M.; Becker, J.T.; Swanson, C.M.; Ahlquist, P.; Sherer, N.M. HIV-1 and M-PMV RNA Nuclear Export Elements Program Viral Genomes for Distinct Cytoplasmic Trafficking Behaviors. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.T.; Sherer, N.M. Subcellular Localization of HIV-1 Gag-Pol MRNAs Regulates Sites of Virion Assembly. J. Virol. 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Nikolaitchik, O.; Singh, J.; Wright, A.; Bencsics, C.E.; Coffin, J.M.; Ni, N.; Lockett, S.; Pathak, V.K.; Hu, W.-S. High Efficiency of HIV-1 Genomic RNA Packaging and Heterozygote Formation Revealed by Single Virion Analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 13535–13540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St Johnston, D. Moving Messages: The Intracellular Localization of MRNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005, 6, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, D.; Bertrand, E.; Singer, R.H. Imaging of Single MRNAs in the Cytoplasm of Living Cells. In RNA Trafficking and Nuclear Structure Dynamics; Progress in Molecular and Subcellular Biology; Jeanteur, P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 35, pp. 135–150. ISBN 978-3-540-74265-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sinck, L.; Richer, D.; Howard, J.; Alexander, M.; Purcell, D.F.J.; Marquet, R.; Paillart, J.-C. In Vitro Dimerization of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) Spliced RNAs. RNA 2007, 13, 2141–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.D.; Nikolaitchik, O.A.; Chen, J.; Hammarskjöld, M.-L.; Rekosh, D.; Hu, W.-S. Probing the HIV-1 Genomic RNA Trafficking Pathway and Dimerization by Genetic Recombination and Single Virion Analyses. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurel, S.; Houzet, L.; Garcia, E.L.; Telesnitsky, A.; Mougel, M. Characterization of a Natural Heterodimer between MLV Genomic RNA and the SD′ Retroelement Generated by Alternative Splicing. RNA 2007, 13, 2266–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurel, S.; Mougel, M. Murine Leukemia Virus RNA Dimerization Is Coupled to Transcription and Splicing Processes. Retrovirology 2010, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.C.; Maldonado, R.J.K.; Parent, L.J. Visualizing Rous Sarcoma Virus Genomic RNA Dimerization in the Nucleus, Cytoplasm, and at the Plasma Membrane. Viruses 2021, 13, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basyuk, E.; Boulon, S.; Skou Pedersen, F.; Bertrand, E.; Vestergaard Rasmussen, S. The Packaging Signal of MLV Is an Integrated Module That Mediates Intracellular Transport of Genomic RNAs. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 354, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagulova, F.; Maurel, S.; Morichaud, Z.; Devaux, C.; Mougel, M.; Houzet, L. The Highly Structured Encapsidation Signal of MuLV RNA Is Involved in the Nuclear Export of Its Unspliced RNA. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 354, 1118–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Wahab, E.W.; Smyth, R.P.; Mailler, E.; Bernacchi, S.; Vivet-Boudou, V.; Hijnen, M.; Jossinet, F.; Mak, J.; Paillart, J.-C.; Marquet, R. Specific Recognition of the HIV-1 Genomic RNA by the Gag Precursor. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muriaux, D.; Darlix, J.-L. Properties and Functions of the Nucleocapsid Protein in Virus Assembly. RNA Biol. 2010, 7, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rein, A. Nucleic Acid Chaperone Activity of Retroviral Gag Proteins. RNA Biol. 2010, 7, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rein, A.; Henderson, L.E.; Levin, J.G. Nucleic-Acid-Chaperone Activity of Retroviral Nucleocapsid Proteins: Significance for Viral Replication. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998, 23, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillart, J.C.; Berthoux, L.; Ottmann, M.; Darlix, J.L.; Marquet, R.; Ehresmann, B.; Ehresmann, C. A Dual Role of the Putative RNA Dimerization Initiation Site of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 in Genomic RNA Packaging and Proviral DNA Synthesis. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 8348–8354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkhout, B.; van Wamel, J.L. Role of the DIS Hairpin in Replication of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1. J. Virol. 1996, 70, 6723–6732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Wu, B.; Nikolaitchik, O.A.; Mohan, P.R.; Chen, J.; Pathak, V.K.; Hu, W.-S. Visualizing the Translation and Packaging of HIV-1 Full-Length RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 6145–6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, L.J. New Insights into the Nuclear Localization of Retroviral Gag Proteins. Nucleus 2011, 2, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbitt-Hirst, R.; Kenney, S.P.; Parent, L.J. Genetic Evidence for a Connection between Rous Sarcoma Virus Gag Nuclear Trafficking and Genomic RNA Packaging. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6790–6797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudleski, N.; Flanagan, J.M.; Ryan, E.P.; Bewley, M.C.; Parent, L.J. Directionality of Nucleocytoplasmic Transport of the Retroviral Gag Protein Depends on Sequential Binding of Karyopherins and Viral RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 9358–9363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, S.P.; Lochmann, T.L.; Schmid, C.L.; Parent, L.J. Intermolecular Interactions between Retroviral Gag Proteins in the Nucleus. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, M.A.; Meyer, M.K.; Decker, G.L.; Arlinghaus, R.B. A Subset of Pr65gag Is Nucleus Associated in Murine Leukemia Virus-Infected Cells. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 1350–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schliephake, A.W.; Rethwilm, A. Nuclear Localization of Foamy Virus Gag Precursor Protein. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 4946–4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyer, A.R.; Bann, D.V.; Rice, B.; Pultz, I.S.; Kane, M.; Goff, S.P.; Golovkina, T.V.; Parent, L.J. Nucleolar Trafficking of the Mouse Mammary Tumor Virus Gag Protein Induced by Interaction with Ribosomal Protein L9. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 1069–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.R. Nuclear MRNA Export: Insights from Virology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003, 28, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield-Gerson, K.L.; Scheifele, L.Z.; Ryan, E.P.; Hopper, A.K.; Parent, L.J. Importin-β Family Members Mediate Alpharetrovirus Gag Nuclear Entry via Interactions with Matrix and Nucleocapsid. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 1798–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaddis Maldonado, R.; Parent, L. Orchestrating the Selection and Packaging of Genomic RNA by Retroviruses: An Ensemble of Viral and Host Factors. Viruses 2016, 8, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Joshi, S.M.; Ma, Y.M.; Kingston, R.L.; Simon, M.N.; Vogt, V.M. Characterization of Rous Sarcoma Virus Gag Particles Assembled In Vitro. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 2753–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheifele, L.Z.; Ryan, E.P.; Parent, L.J. Detailed Mapping of the Nuclear Export Signal in the Rous Sarcoma Virus Gag Protein. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 8732–8741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheifele, L.Z.; Garbitt, R.A.; Rhoads, J.D.; Parent, L.J. Nuclear Entry and CRM1-Dependent Nuclear Export of the Rous Sarcoma Virus Gag Polyprotein. PNAS 2002, 99, 3944–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado, R.J.K.; Rice, B.; Chen, E.C.; Tuffy, K.M.; Chiari, E.F.; Fahrbach, K.M.; Hope, T.J.; Parent, L.J. Visualizing Association of the Retroviral Gag Protein with Unspliced Viral RNA in the Nucleus. mBio 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, F.P.; Sandri-Goldin, R.M. Bimolecular Fluorescence Complementation Analysis to Reveal Protein Interactions in Herpes Virus Infected Cells. Methods 2011, 55, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuffy, K.M.; Maldonado, R.J.K.; Chang, J.; Rosenfeld, P.; Cochrane, A.; Parent, L.J. HIV-1 Gag Forms Ribonucleoprotein Complexes with Unspliced Viral RNA at Transcription Sites. Viruses 2020, 12, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, S.; Sharova, N.; DéHoratius, C.; Virbasius, C.-M.A.; Zhu, X.; Bukrinskaya, A.G.; Stevenson, M.; Green, M.R. A Novel Nuclear Export Activity in HIV-1 Matrix Protein Required for Viral Replication. Nature 1999, 402, 681–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, E.; Strappe, P.; Mok, H.-P.; Hicks, R.; Lever, A.M.L. HIV-1 Gag-RNA Interaction Occurs at a Perinuclear/Centrosomal Site; Analysis by Confocal Microscopy and FRET: HIV-1 Gag-RNA Interaction Occurs in a Perinuclear Region. Traffic 2005, 6, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgärtel, V.; Müller, B.; Lamb, D.C. Quantitative Live-Cell Imaging of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV-1) Assembly. Viruses 2012, 4, 777–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digman, M.A.; Stakic, M.; Gratton, E. Raster Image Correlation Spectroscopy and Number and Brightness Analysis. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 518, pp. 121–144. ISBN 978-0-12-388422-0. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, S.S.; Hunter, E. Myristylation Is Required for Intracellular Transport but Not for Assembly of D-Type Retrovirus Capsids. J. Virol. 1987, 61, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, A.M.; Oroszlan, S. In Vivo Modification of Retroviral Gag Gene-Encoded Polyproteins by Myristic Acid. J. Virol. 1983, 46, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houzet, L.; Gay, B.; Morichaud, Z.; Briant, L.; Mougel, M. Intracellular Assembly and Budding of the Murine Leukemia Virus in Infected Cells. Retrovirology 2006, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blot, V.; Perugi, F.; Gay, B.; Prévost, M.-C.; Briant, L.; Tangy, F.; Abriel, H.; Staub, O.; Dokhélar, M.-C.; Pique, C. Nedd4.1-Mediated Ubiquitination and Subsequent Recruitment of Tsg101 Ensure HTLV-1 Gag Trafficking towards the Multivesicular Body Pathway Prior to Virus Budding. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 2357–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basyuk, E.; Galli, T.; Mougel, M.; Blanchard, J.-M.; Sitbon, M.; Bertrand, E. Retroviral Genomic RNAs Are Transported to the Plasma Membrane by Endosomal Vesicles. Dev. Cell 2003, 5, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouvenet, N.; Lainé, S.; Pessel-Vivares, L.; Mougel, M. Cell Biology of Retroviral RNA Packaging. RNA Biol. 2011, 8, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsch, S.; Keppler, O.T.; Habermann, A.; Allespach, I.; Krijnse-Locker, J.; Kräusslich, H.-G. HIV-1 Buds Predominantly at the Plasma Membrane of Primary Human Macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2007, 3, e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladnikoff, M.; Rousso, I. Directly Monitoring Individual Retrovirus Budding Events Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saffarian, S.; Kirchhausen, T. Differential Evanescence Nanometry: Live-Cell Fluorescence Measurements with 10-Nm Axial Resolution on the Plasma Membrane. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 2333–2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, P.-I.; Miller, A.K.; Ballew, J.; Sandrin, V.; Adler, F.R.; Saffarian, S. Identification of Pauses during Formation of HIV-1 Virus Like Particles. Biophys. J. 2013, 105, 2262–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemler, I.; Barraza, R.; Poeschla, E.M. Mapping the Encapsidation Determinants of Feline Immunodeficiency Virus. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 11889–11903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerviel, A.; Thomas, A.; Chaloin, L.; Favard, C.; Muriaux, D. Virus Assembly and Plasma Membrane Domains: Which Came First? Virus Res. 2013, 171, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, E.R.; Göttlinger, H. The Role of Cellular Factors in Promoting HIV Budding. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J.H.; Boura, E.; Carlson, L.-A.; Różycki, B. Membrane Budding. Cell 2010, 143, 875–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Serrano, J.; Neil, S.J.D. Host Factors Involved in Retroviral Budding and Release. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingler, J.; Anton, H.; Réal, E.; Zeiger, M.; Moog, C.; Mély, Y.; Boutant, E. How HIV-1 Gag Manipulates Its Host Cell Proteins: A Focus on Interactors of the Nucleocapsid Domain. Viruses 2020, 12, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouland, A.J.; Mercier, J.; Luo, M.; Bernier, L.; DesGroseillers, L.; Cohen, É.A. The Double-Stranded RNA-Binding Protein Staufen Is Incorporated in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1: Evidence for a Role in Genomic RNA Encapsidation. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 5441–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatel-Chaix, L.; Clément, J.-F.; Martel, C.; Bériault, V.; Gatignol, A.; DesGroseillers, L.; Mouland, A.J. Identification of Staufen in the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Gag Ribonucleoprotein Complex and a Role in Generating Infectious Viral Particles. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 24, 2637–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itano, M.S.; Arnion, H.; Wolin, S.L.; Simon, S.M. Recruitment of 7SL RNA to Assembling HIV-1 Virus-like Particles. Traffic 2018, 19, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strebel, K.; Khan, M.A. APOBEC3G Encapsidation into HIV-1 Virions: Which RNA Is It? Retrovirology 2008, 5, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hell, S.W.; Wichmann, J. Breaking the Diffraction Resolution Limit by Stimulated Emission: Stimulated-Emission-Depletion Fluorescence Microscopy. Opt. Lett. 1994, 19, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, M.J.; Bates, M.; Zhuang, X. Sub-Diffraction-Limit Imaging by Stochastic Optical Reconstruction Microscopy (STORM). Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betzig, E.; Patterson, G.H.; Sougrat, R.; Lindwasser, O.W.; Olenych, S.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Davidson, M.W.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Hess, H.F. Imaging Intracellular Fluorescent Proteins at Nanometer Resolution. Science 2006, 313, 1642–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, H.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y. Super-Resolution Fluorescence Microscopy for Single Cell Imaging. In Single Cell Biomedicine; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Gu, J., Wang, X., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; Volume 1068, pp. 59–71. ISBN 9789811305016. [Google Scholar]

- Han, R.; Li, Z.; Fan, Y.; Jiang, Y. Recent Advances in Super-Resolution Fluorescence Imaging and Its Applications in Biology. J. Genet. Genom. 2013, 40, 583–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).