Abstract

Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb) is a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) with an antipathogenic activity. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules that are ubiquitously expressed in cells. Endogenous miRNA may function as an innate response to block pathogen invasion. The miRNA expression profiles of both mice and humans after the ingestion of honeysuckle were obtained. Fifteen overexpressed miRNAs overlapped and were predicted to be capable of targeting three viruses: dengue virus (DENV), enterovirus 71 (EV71) and SARS-CoV-2. Among them, let-7a was examined to be capable of targeting the EV71 RNA genome by reporter assay and Western blotting. Moreover, honeysuckle-induced let-7a suppression of EV71 RNA and protein expression as well as viral replication were investigated both in vitro and in vivo. We demonstrated that let-7a targeted EV71 at the predicted sequences using luciferase reporter plasmids as well as two infectious replicons (pMP4-y-5 and pTOPO-4643). The suppression of EV71 replication and viral load was demonstrated in two cell lines by luciferase activity, RT-PCR, real-time PCR, Western blotting and plaque assay. Furthermore, EV71-infected suckling mice fed honeysuckle extract or inoculated with let-7a showed decreased clinical scores and a prolonged survival time accompanied with decreased viral RNA, protein expression and virus titer. The ingestion of honeysuckle attenuates EV71 replication and related pathogenesis partially through the upregulation of let-7a expression both in vitro and in vivo. Our previous report and the current findings imply that both honeysuckle and upregulated let-7a can execute a suppressive function against the replication of DENV and EV71. Taken together, this evidence indicates that honeysuckle can induce the expression of let-7a and that this miRNA as well as 11 other miRNAs have great potential to prevent and suppress EV71 replication.

1. Introduction

Honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb) is a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). The aqueous extract of the flower bud can relieve fever and flu-like symptoms [1]. The active ingredients of honeysuckle flower extract include chlorogenic acid and isochlorogenic acid [1], which can suppress microbial activities both in vitro and in vivo. We have reported that ingestion of honeysuckle upregulates the innate microRNA (miRNA) let-7a to attenuate dengue virus-2 (DENV-2) replication and related pathogenesis both in vitro and in vivo [2]. In the present study, we further predicate that honeysuckle upregulated miRNAs including let-7a could target EV71 and SARS-CoV-2 according to our previous findings [2].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules (containing about 22 nucleotides) involved in the regulation of many cellular functions and immune responses [3,4,5,6]. MiRNAs may regulate viral activity by targeting viral RNA genomes at the 5′UTR, 3′UTR or coding region of mRNA [6,7,8,9,10]. MiRNAs bind with specific targeting sites resulting in either degradation of the targeted RNA or blockage of translation. The highly permeable miRNAs in body fluid, tissues and organs have been used as biomarkers for disease diagnosis [11,12] and execute bioactivities located in cytoplasm, nucleus, mitochondria and even distant recipient cells by transportation through exosomes [10,13,14]. There is a growing interest in the use of miRNA-related immune responses to mitigate the effects of defective antibody production for the prevention or suppression of infectious diseases.

Enterovirus 71 (EV71) belongs to the enterovirus genus of the picornaviridae family and can be classified into three groups (A, B, C) and 11 genotypes (A, B1–5 and C1–5) [15,16]. EV71 contains a 7.5 kb single-stranded (+) RNA genome with a 5′untranslated region (UTR), a coding region, and 3′ UTR. Ribosomes travel from the 5′ end to the 3′ end of the RNA genome to synthesize a polyprotein in a cap-independent manner [17]. This polyprotein matures into 11 proteins including four capsid proteins (VP1–4) and seven non-structural proteins (2A, 2B, 2C, 3A, 3B, 3C, 3D) [18] through cleavage by viral proteases [19]. Before the viral genome RNA is encapsidated, VP0 is further cleaved into VP2 and VP4 by an autocatalytic mechanism [20]. EV71 patients generally show symptoms ranging from mild hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) to severe EV71-associated neurological complications. Although the symptoms of HFMD can be induced by EV71 and Coxsackie A 16 viruses, only the former can induce brain encephalitis [21] and high mortality [22]. The average mortality of EV71 is in the range of 13% to 15.7% [23,24]. Neurological complications include the inflammation of the cerebral cortex, brain stem and spinal cord, which leads to aseptic meningitis, brain stem encephalitis, motor neuron death and acute flaccid paralysis [19,23,25]. EV71 can infect fibroblasts, epithelium, cells of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts and dendritic cells [19,21]. EV71 can evade the human immune surveillance system including both the systemic immune system and the innate immune system [21]. One of the mechanisms involves inhibiting the host cell interferon type I response through EV71 protein 3C, which enhances viral replication and promotes the pathological outcome of encephalitis [21]. EV71-infected lymphocytes and leucocytes bring EV71 across the blood-brain barrier and thus assist in the introduction of EV71 into the central nervous system [21] and promote the pathogenesis of encephalitis. EV71-induced brain stem encephalitis enhances catecholamine, cytokine and chemokine concentrations in vivo, which promote EV71-related immunopathogenesis [19]. Most of the severe symptoms occur in young children around 12 months old. Adults infected by EV71 are generally asymptomatic or present with mild symptoms [24]. Severe brain encephalitis may be caused by the evolution of EV71 [22,25,26,27]. However, there are still no effective antiviral treatments for EV71 infection. Therefore, it is urgent to develop an effective therapeutic agent or preventive vaccine.

SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) emerged in late 2019 and rapidly became a pandemic [28]. It is a single-stranded (+) RNA virus and a member of the beta-coronavirus genus including SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [29,30]. Mortality in SARS-CoV-2 is caused by hyper-inflammation of the lung, which subsequently leads to acute respiratory distress/failure (ARDS) [31]. Most COVID-19 patients with ARDS are characterized by markedly elevated cytokine levels including interleukin (IL)-2, IL-6, IL-7, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), interferon-γ inducible protein 10 (CXCL10), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (CCL2), macrophage inflammatory protein 1-α (CCL3) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [32]. Unlike with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, corticosteroids exacerbate SARS-CoV-2-associated lung injury as this virus may drive immunosuppression [33]. SARS-CoV-2 utilizes the spike glycoprotein on the envelope to bind the cellular receptor ACE2 and TMPRSS2 for cell entry [34]. To prevent the overload of medical support, there is an urgent demand for effective therapeutic drugs and preventive vaccines [35]. Among the potential targets for the suppression of SARS-CoV-2, a few studies have investigated repurposing drugs or small molecules that inhibit ACE2 and TMPRSS2 [34,36]. However, these two receptors are detected in many organs and blocking ACE2 or TMPRSS2 may cause unwanted side effects particularly when potential antiviral agents are systemically administrated in patients with multiple comorbidities [37,38]. However, most known mechanisms of antiviral agents target a limited number of pathways, which may not be related to the pathophysiology of SARS-CoV-2 infection and such agents may cause intolerable adverse effects [39]. Concerning the safety of antiviral agents, the use of TCM warrants further exploration as various plant-derived compounds in TCM have been shown to exert minimal toxicities or have only mild side effects [40,41,42]. Although numerous complex TCM formulae have been investigated to determine their therapeutic effects against COVID-19, the findings of most such studies are largely based on patients’ self-reported symptoms and the mechanism of action is generally not discussed [43]. Despite the large number of patents related to plant-derived compounds with a putative therapeutic value in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 [44], the use of structure-based screening remains a considerable challenge as the results of the aforementioned research efforts have not been functionally validated in vitro or in vivo [45]. Due to strict restrictions on the use of SARS-CoV-2 and the limited availability of suitable research facilities, it is difficult to directly investigate the activity of this virus in general laboratories.

Our previous study on the antiviral activity of honeysuckle revealed that inducing host innate miRNAs may have the potential to block the spread and infection of various viruses [2]. To extend this concept, herein we attempted to determine whether honeysuckle upregulated let-7a could target EV71 at predicted regions and alleviate its replication and pathogenesis. Taken together, our findings confirm the therapeutic effects of miRNA let-7a induced by honeysuckle aqueous extract on EV71 infection. Thus, we also predicate that honeysuckle-induced miRNAs including let-7a are potential antiviral agents against SARS-CoV-2 and may suppress the replication of SARS-CoV-2. Our encouraging findings warrant further investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Honeysuckle Aqueous Extract Preparation and Analysis of Blood miRNA Expression Profiles in Human Participants and Mice after Ingestion

Dried honeysuckle flowers were purchased, identified and the fingerprint of compounds in the honeysuckle aqueous extracts was determined by UPLC-Q/TOF MS as described in the previous report [2]. A human volunteer assessment was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of National Cheng Kung University Hospital (IRB approval number IBR-99-127). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Animal welfare and experimental studies followed the guidelines of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996) and this study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Model Animal Research Center (MARC) of Nanjing University and the IACUC of National Cheng Kung University (approval number No. 101291). The experimental procedure on the human subjects and the mice as well as the analysis of blood miRNA profiles were described in detail in the previous report [2]. The miRBase website (http://www.mirbase.org, accessed on 1 May 2021) was used to search for human homologues of the endogenous matched miRNAs of the mice [46]. The miRNA sequences (from “miRBase 22 release”) and the viral sequences (SARS-COV-2: NCBI accession number NC045512; DENV2 PL046: NCBI accession number AJ968413; EV71 71-4643-TW98: NCBI accession number AF304458) were queried by “miranda v3.3a” to predict the miRNA target sequences of virus genomes using the following parameters: scaling parameter: 4; gap open penalty: −4; gap extension penalty: −3; score threshold: 140; minimum free energy threshold: −18. The family of clustering and seed sequence group of the miRNAs were analyzed using the “smirnaDB” platform (http://www.mirz.unibas.ch/cloningprofiles, accessed on 1 May 2021).

2.2. Prediction of Honeysuckle-Induced miRNA and Pathway Analysis

The proteins or genes targeted by the ingredients of honeysuckle were obtained from “SymMap” (https://www.symmap.org/, accessed on 1 May 2021), a comprehensive TCM database that integrates 499 TCM herbs registered in the Chinese pharmacopoeia with 19,595 ingredients and the corresponding 4302 genetic targets [47]. The genetic target values were filtered by different values of false discovery rate using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (FDR-BH). All significant genetic targets were used to query the miRNA of interest in our prediction list using the “g:Profiler” (https://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/, accessed on 1 May 2021) platform [48,49]. In this web-based tool, the statistical domain scope was set as “all known genes” and the significance threshold was set as “Benjamini–Hochberg FDR 0.05”.

Likewise, all data of interest pertaining to significant genetic targets can be used for pathway analysis by querying the free public online software “ConsensusPathDB” (CPDB) (http://cpdb.molgen.mpg.de/, accessed on 1 May 2021) or the commercial platform “Ingenuity Pathways Analysis” (IPA). CPDB provides information on integration networks in Homo sapiens including genetic, signaling, drug-target interactions and biochemical pathways. Data originate from 32 public resources and interactions that have been curated from the literature [50]. The parameters used for the over-representation analysis in CPDB include all 13 available databases and a cutoff p-value set as 0.05. IPA is a commercial web-based software package, which provides causal analysis approaches with a particular focus on the precise underlying upstream biological causes and probable downstream effects on cellular and organismal biology [51]. In the core analysis part of IPA, the cutoff p-value is set as 0.05.

2.3. Cell Culture and Viruses

A human rhabdomyosarcoma RD cell line (ATCC, CCL-136), a human neuroblastoma SK-N-SH cell line (ATCC, HTB-11) and a human kidney HEK 293T cell line (ATCC, CRL-11268) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; GIBCO-BRL, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing L-glutamine and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Trace Bioscience, Sydney, Australia). Monkey kidney BT7-H cells (a gift from Stanley Lemon, University of Texas Medical Branch) were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and Geneticin™ (G-418 sulfate; Life Technologies, Grand Island, New York, USA). Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

The enterovirus 71 Tainan strain 4643/98 (EV71/4643; NCBI accession number AF304458) was propagated for one generation in RD cells before use. The mouse-adapted EV71 MP4 strain (EV71 MP4; NCBI accession number JN544419) [52,53] derived from the EV71/4643 strain was used to infect ICR mice (a gift from Dr. Chun-Keung Yu, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan).

Human RD or SK-N-SH cells were cultured in a 6-well plate (3 × 105 cells/well) overnight at 37 °C, followed by a replacement with a fresh DMEM medium containing 2% FBS in the presence or absence of EV71. The cells were maintained for the indicated times and harvested for analysis.

2.4. Plaque Assay

RD cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were plated onto a 24-well plate (NUNC, Roskilde, Denmark) and placed at 37 °C for 16–20 hr. After removing the medium, cells were infected with the virus with DMEM containing 2% FBS (200 μL/well). After absorption at 37 °C for 1 hr, the viral suspension was replaced with a two-fold DMEM containing 2% FBS and 1% methyl cellulose solution (American Biorganics, Niagara Falls, NY, USA). The overlay medium was poured off at 72 hr post-infection (PI) and a 10% crystal violet solution was added for 15 min until it colored the cytoplasm. The excess was gently removed with water to show the uncolored location of dead cells (plaque). The viral titer was expressed as plaque-forming units per milliliter (pfu/mL).

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

At the indicated times after EV71 infection, the culture medium was removed and the cells in the 6 cm culture plates were washed twice with PBS followed by lysis with 50 μL of a radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA buffer; 10 μL of PMSF (0.1 M), 10 μL of aprotinin (2 mg/mL), 20 μL of EGTA (0.1 M), 5 μL of leupeptin (2 mg/mL) and 4 μL of sodium orthovanadate (Na3VO4, 0.5 M)). The cell lysates were harvested by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm at 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatants were collected and the protein was quantified by Bicinchoninic Acid (BCA) kits (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The proteins were analyzed by the sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) followed by a transfer onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore, Boston, MA, USA). The membrane was incubated with a TBST (tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 detergent) blocking solution plus 5% non-fat dried milk for 1 hr followed by washing with TBST. The mouse monoclonal anti-EV71 VP2 antibody (1:2000 in TBST; Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA) and mouse monoclonal anti-beta-actin antibody (1:5000 in TBST; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used as the primary antibodies. After incubation at 4 °C overnight, the membranes were washed with TBST and followed by incubation with the secondary anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (1:5000; Chemicon, USA) for 1 hr at room temperature (RT). Finally, membranes were incubated with an ImmobilonTM Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore) and examined using X-ray films. The protein level was measured and quantified using VisionWorksTM LS image acquisition and analysis software (UVP, Upland, CA, USA).

2.6. Reporter Plasmids and Luciferase Assay

The wild-type and mutant sequences of EV71 5′UTR 233–254 and VP2 1234–1256 were cloned into Ambion® pMIR-REPORTTM miRNA Expression Reporter plasmid (Invitrogen) to form pMIR-5′UTR, pMIR-VP2 and their corresponding mutants.

Human HEK293T cells were co-transfected with miRNA let-7a, the reporter plasmid DNA of pMIR-5′UTR, pMIR-VP2 or their corresponding mutants and the internal control reporter plasmid pRL-TK Vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) by transient transfection using TurboFectTM Transfection Reagent (Fermentas, Sankt Leon-Rot, Germany). The cells were harvested at 24 h for luciferase assay using the Dual-Luciferase® Reporter Assay System (Promega). The luciferase activity was determined using a Mini-Lumat LB9506 luminometer (Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Each treatment was measured in triplicate and the experiment was performed three times independently.

2.7. RT-PCR and Real-Time PCR

EV71 positive-stranded (+) or negative-stranded (−) RNA was reversely transcribed into cDNA using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). To determine the level of (+) or (−) strand EV71 RNA, PCR was performed to evaluate the level of VP2 (as an indicator of EV71 RNA level) using a YEA DNA polymerase (Yeastern Biotech, Taipei, Taiwan). An NCode™ VILO™ miRNA cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen) was used to reversely transcribe miRNA let-7a into cDNA and NCodeTM and SYBRTM Green miRNA qRT-PCR Kits (Invitrogen) were used for analysis. Real-time PCR was conducted using the Step One Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

For the construction of the pMIR reporter plasmids, the primers used were as follows:

The wild-type 5′UTR of EV71 was 5′-AATGCACTAGTCGTTACCCGGACCAACTACTTCAGCTCAGCAAGCTTAATGC-3′.

The wild-type antisense of 5′UTR of EV71 was 5′-GCATTAAGCTTGCTGAGCTGAAGTAGTTGGTCCGGGTAACGACTAGTGCATT-3′.

The mutant 5′UTR of EV71 was 5′-AATGCACTAGTCCAATGCGGTCGATGAAGTACCGCTCAGCAAGCTTAATGC-3′.

The mutant antisense of 5′UTR of EV71 was 5′-GCATTAAGCTTGCTGAGCGGTACTTCATCGACCGCATTGGACTAGTGCATT-3′.

The wild-type VP2 of EV71 was 5′-AATGCACTAGTAAATGCACAGTTCCACTACCTCTAGCTCAGCAAGCTTAATGC-3′.

The wild-type antisense VP2 of EV71 was 5′-GCATTAAGCTTGCTGCGCCTAGAGGTAGTGGAACTGTGCATTTACTAGTGCAT-3′.

For the RT-PCR analysis, the primers used were as follows:

The negative strand (-) VP2 was 5′-GGCCACTCACCATAGCCAACTA-3′.

The (−) VP2 forward was 5′-ATCCGGGAATTTCCAGTACC-3′.

The (−) VP2 reverse was 5′-GCAAGAAGCAGCAAACATCA-3′.

For real-time PCR and RT-PCR, the primers used were as follows:

The VP2 forward was 5′-ACCCTTTGATTCTGCCTTGA-3′.

The VP2 reverse was 5′-CCTTGCGTAACTGCTTGTC-3′.

For endogenous β-actin mRNA, the primers used were as follows:

The β-actin-F was 5′-GGCGGCACCACCATGTACCCT-3′.

The β-actin-R was 5′-AGGGGCCGGACTCGTCATACT-3′.

For let-7a, the snoRNA55 of mice and the U54 of humans were as follows:

The hsa-let-7a was 5′-GCCTGAGGTAGTAGGTTGTATAGTTA-3′.

The snoRNA55 (Mus) was 5′-TGACGACTCCATGTGTCTGAGCAA-3′.

The U54 (homo) was 5′-GGTACCTATTGTGTTGAGTAACGGTGA-3′.

2.8. Suckling Mouse Model for EV71 Infection

To evaluate the effect of honeysuckle or let-7a on EV71 replication and related pathogenesis in vivo, the EV71 MP4 mouse-adapted strain and ICR suckling mice were used [54]. Despite that this suckling mouse model of EV71 infection could not present the clinical symptoms that mimicked infection in humans, it may serve as an indicative model for an evaluation of EV71 virulence, replication and pathogenesis. The 7-day-old ICR suckling mice were obtained from the Animal Research Center of National Cheng Kung University. The EV71 (MP4 strain) was intracranially (IC) inoculated into the ICR suckling mice (25 μL or 50 μL in 2.5 × 105 pfu/mouse or 5 × 105 pfu/mouse, respectively) using a 30-gauge needle and 2% FBS/DMEM was used for the mock infection.

Initially, the effect of honeysuckle ingestion on let-7a miRNA levels in the blood of the suckling mice was evaluated. For a mouse with a body weight of 4 g, a dose of 0.0008 g of honeysuckle in 40 mL of ddH2O was given using a 1 mL syringe. The control group of mice was fed boiled ddH2O. The 6-day-old ICR suckling mice were fed the honeysuckle aqueous extract twice a day for four consecutive days. The mice were then sacrificed followed by the collection of the brain tissues and blood samples. The investigation of the effects of let-7a on EV71 MP4-infected ICR suckling mice was conducted by intracranial inoculation using a micro-injection syringe.

EV71 MP4-infected mice with either honeysuckle or let-7a treatment were evaluated according to the following disease scores: 0: healthy; 1: ruffled hair, hunchbacked or reduced mobility; 2: wasting; 3: forelimb or hindlimb weakness; 4: forelimb or hindlimb paralysis; 5: death. The levels of viral genes and proteins as well as the titers in the mice brains were measured. For the collection of brain samples, the mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (5 mg/mouse; Nembutal; Abbott Lab., North Chicago, IL, USA) and then tissue samples were aseptically removed, weighed and homogenized either in 1 mL of 2% FBS/DMEM (for preparing the virus solution), 500 mL of TRIzol (for extracting the RNA) or 500 mL of a RIPA lysis buffer (for extracting protein).

3. Results

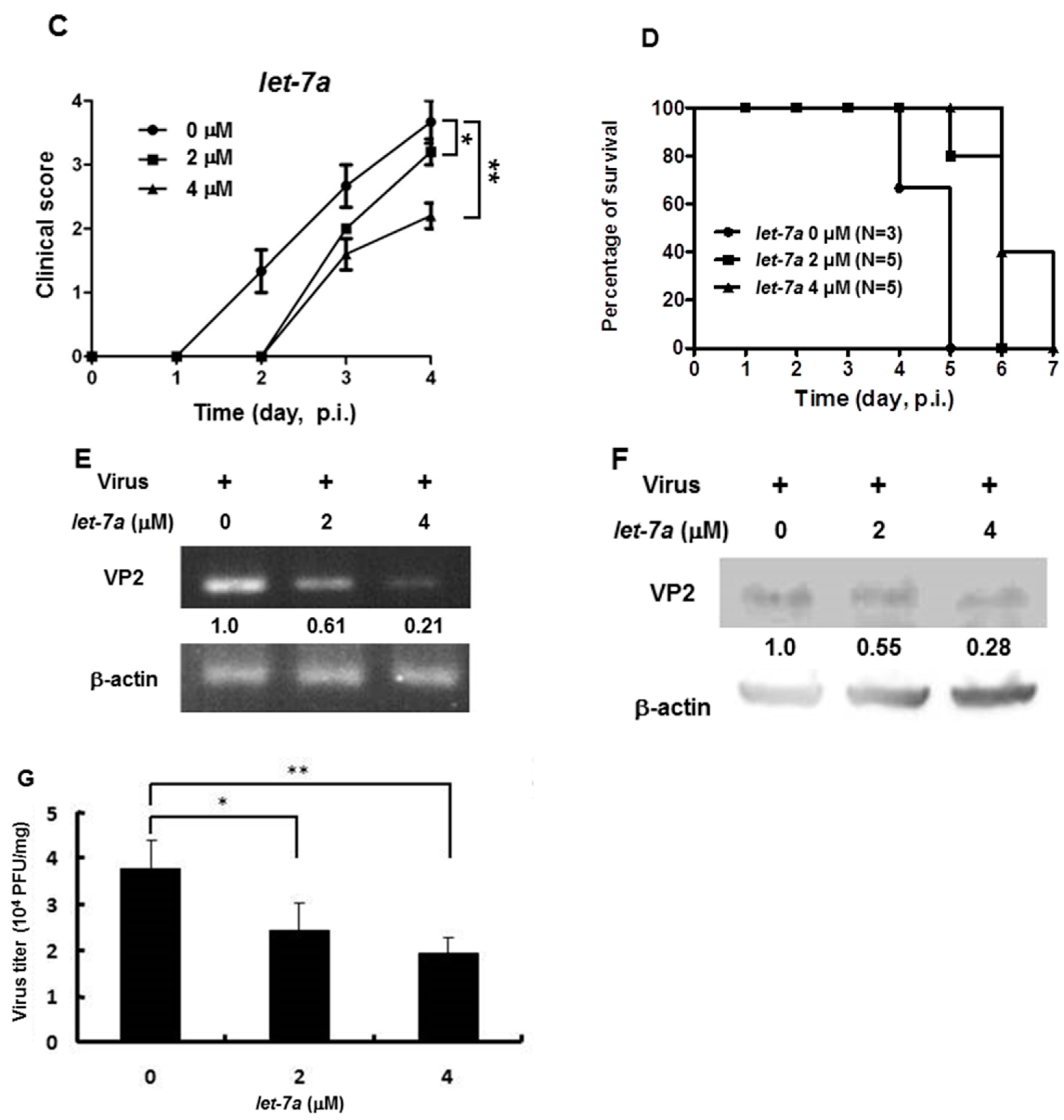

3.1. Honeysuckle-Induced Host miRNAs Both in Mice and Humans Were Predicted to Be Capable of Targeting Genome Sequences of SARS-CoV-2, DENV and EV71

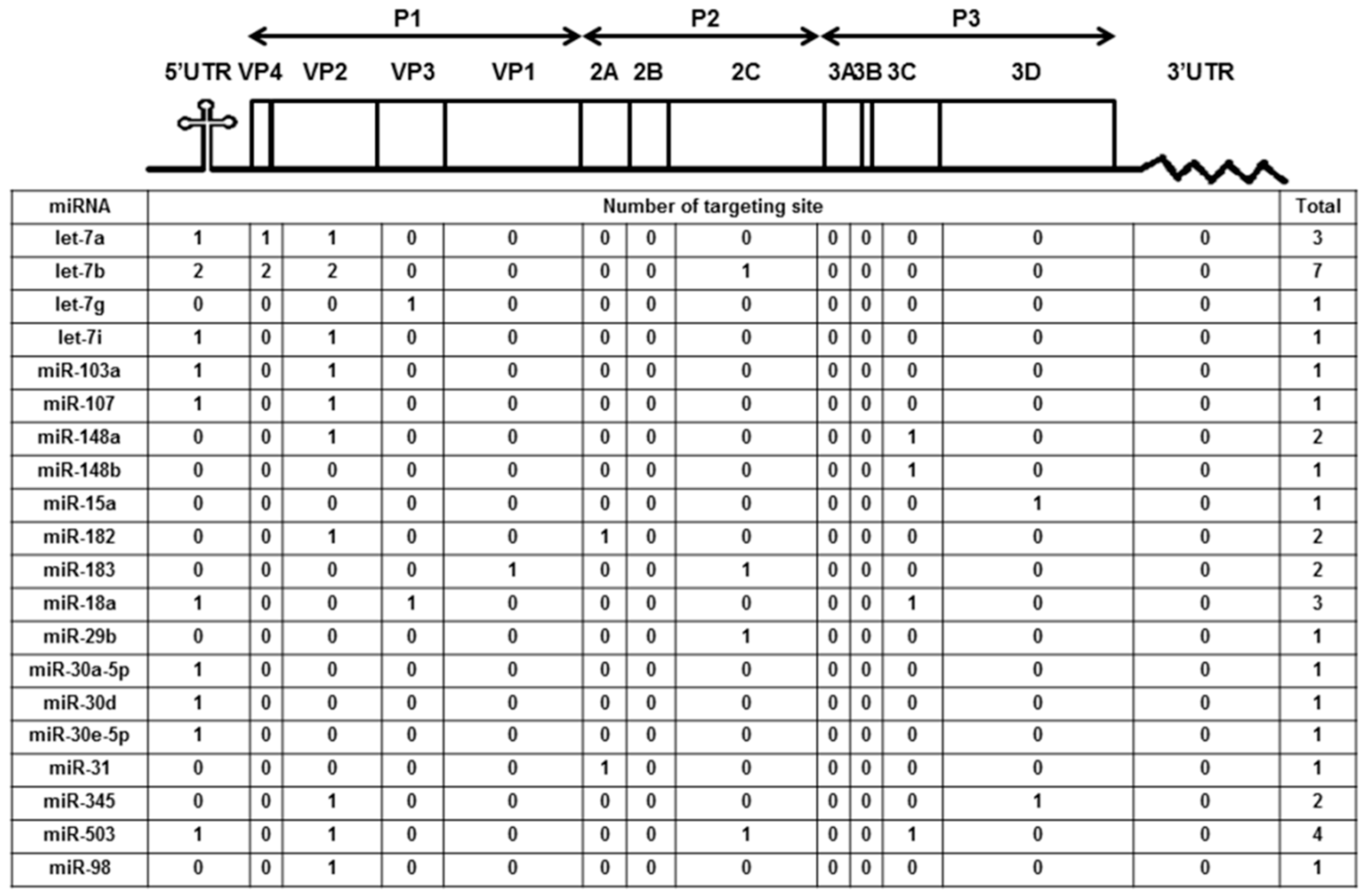

We previously reported the differentially expressed miRNAs both in mice (10 weeks old) and human volunteers (23 to 30 years old) after ingesting honeysuckle for four consecutive days (twice a day) [2]. Among them, a total of 20 upregulated miRNAs both in mice and humans were predicted to be capable of targeting the EV71/4643 genome (Accession No. AF304458) at multiple regions (Figure 1). Moreover, 15 overlapping miRNAs in the mice and human groups were predicted to be able to target the genome sequences of SARS-CoV-2, DENV2 and EV71 (Supplementary Table S1). These data imply that the ingestion of honeysuckle both in mice and humans could induce a similar group of host miRNAs that have the potential to specifically target the genome of invading pathogens especially RNA viruses such as SARS-CoV-2, DENV-2 and EV71. To confirm that honeysuckle upregulated miRNA can indeed target these viruses and can attenuate viral replication, the effects of honeysuckle-mediated let-7a on EV71 infection both in vitro and in vivo was evaluated.

Figure 1.

Honeysuckle ingestion induced twenty miRNAs both in mice and humans that are able to recognize the EV71 genome at various regions and the corresponding proteins. Four hundred 10-week-old C57/B6 mice and 17 healthy human volunteers ingested honeysuckle aqueous extract as described in the Methods. The upregulated endogenous miRNAs in the blood of the mice and humans were determined [2]. The overlapped miRNAs between mice and humans predicted to be able to target EV71 at multiple regions by “miranda v3.3a” are illustrated. The miRNA sequences were from “miRBase 22 release” and the viral sequences were from the Nucleotide database of NCBI (Accession No. AF304458).

3.2. In Silico Prediction of Honeysuckle-Related Pathways Are Highly Correlated to Diverse Virus Infections and Regulation of Cytokines

The abovementioned 159 significant genes were used to query “CPDB” and “IPA” platforms for possible pathways. The canonical pathway analysis showed that honeysuckle participated in various viral infection mechanisms (Table 1 and Table 2) such as cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, herpes virus, human T-cell leukemia virus 1, human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection, papillomavirus and Ebola virus. There was also a large number of cytokine-related pathways corresponding to the honeysuckle genetic targets especially IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and IL-17, which were highly correlated to the cytokine storm in ARDS. In addition, the Ras activation signaling pathway was also targeted by honeysuckle, which was consistent with our previous finding [2].

Table 1.

The canonical pathway analysis by ConsensusPathDB (CPDB) §.

Table 2.

The canonical pathway analysis by Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) §.

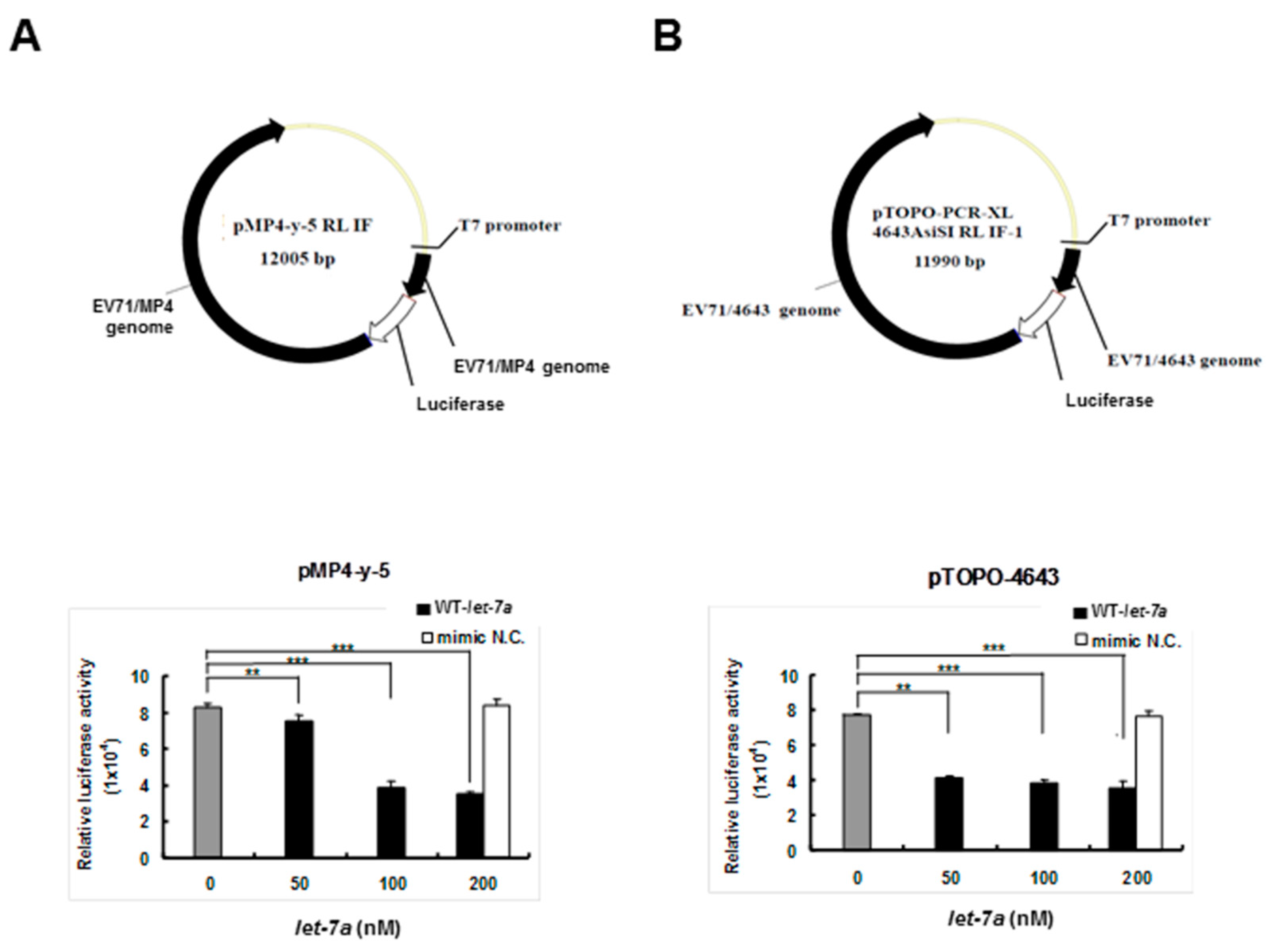

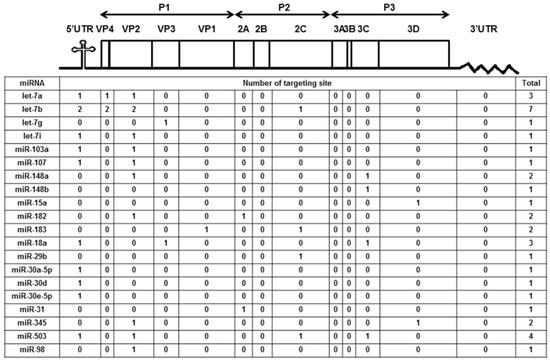

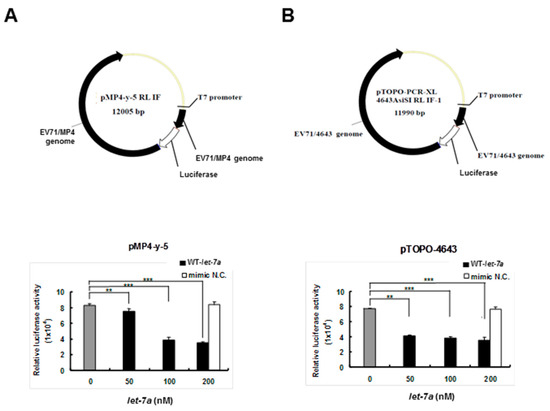

3.3. Let-7a Bound with Two EV71 Replicon Clones and Attenuated Luciferase Activity

To clarify whether let-7a specifically targeted EV71 RNA genome sequences, two firefly luciferase reporter gene recombinant plasmids containing the genome replicon of either EV71 strain 4643 (pTOPO-4643) or mouse-adapted strain MP4 (pMP4-y-5P) (a gift from Dr. Jen-Ren Wang, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan) [55] were co-transfected together with the exogenous let-7a into BT7-H cells, which expressed T7 RNA polymerase to drive the viral gene expression of the recombinant plasmids. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cellular protein was extracted and analyzed for dual luciferase activity using a luminometer. The results showed that the transfected let-7a significantly inhibited the luciferase activities of both pMP4-y-5p (Figure 2A) and pTOPO-4643 plasmids (Figure 2B) in a dose-dependent manner and the negative control miRNA (NC) showed no inhibition. This result implied that let-7a may target the RNA genome of the two EV71 strains.

Figure 2.

Let-7a suppressed the expression levels of 4643 and MP4 strain-infected EV71 clones in BT7-H cells. BT7-H cells were co-transfected with infectious clone plasmids (pMP4-y-5 and pTOPO-4643) and different concentrations of let-7a by TurboFectTM. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were harvested and protein lysate was subjected to the luciferase assay by a dual luciferase reporter assay system. The relative luciferase activity is shown in (A) for strain MP4 pMP4-y-5 and (B) strain 4643 pTOPO-4643. Mimic NC miRNA: scrambled sequence of let-7a. The relative luciferase activity was normalized with Renilla luciferase. **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001

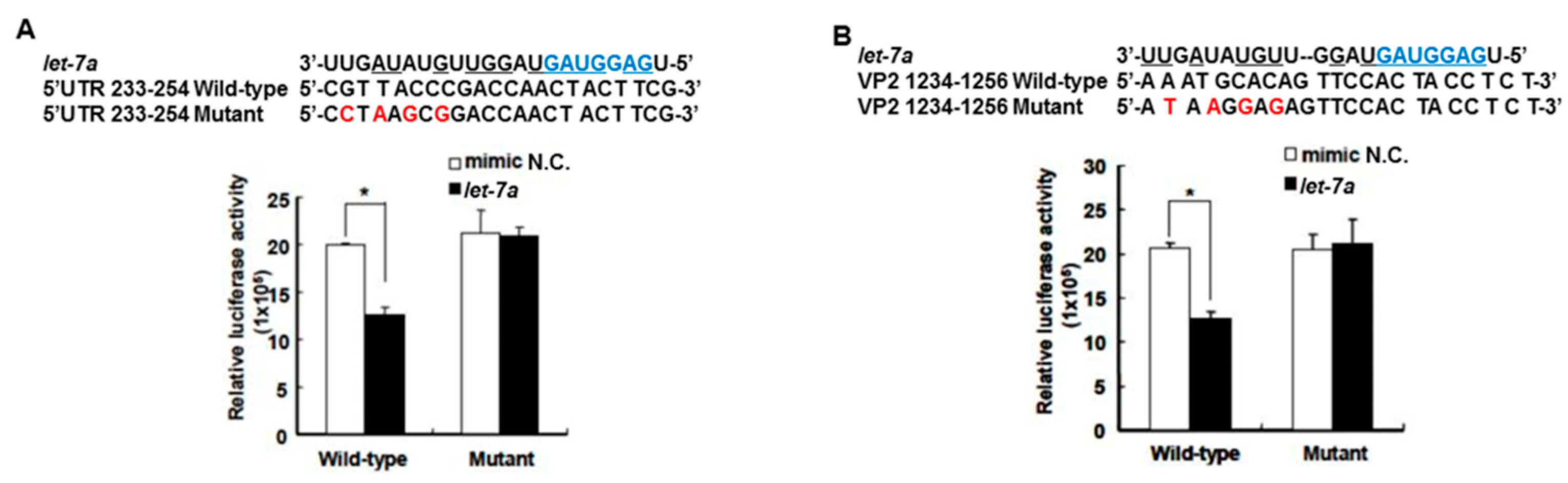

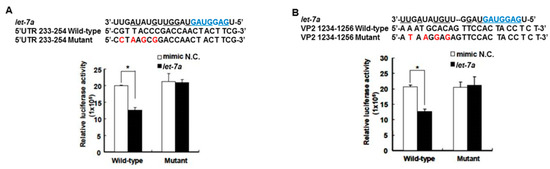

3.4. Let-7a Was Confirmed to Specifically Target the EV71 Genome at Two Regions, 5′UTR 233–254 and VP2 1234–1256

The target gene predicted by “miranda v3.3a” software revealed that among the miRNAs induced by the honeysuckle aqueous extract, let-7a was capable of targeting EV71 genome at three regions, 5′UTR 233–254, VP4 814–836 and VP2 1234–1256 (Figure 1). A sequence alignment analysis revealed that the sequences of 5′UTR were highly conserved among several enterovirus strains (Supplementary Table S2) [56,57]. The alignments of the EV71 5′UTR 233–254 and VP2 1234–1256 regions with predicted let-7a targeting sequences are shown in Figure 3 and the targeting score was higher than that for EV71 VP4 814–836. To verify the targeting capability of let-7a on these two regions, the luciferase reporter plasmids harboring either wild-type or mutant sequences of EV71 5′UTR 233–254 and VP2 1234–1256 regions were constructed. Exogenous let-7a and the corresponding reporter plasmid were co-transfected into the human embryonic kidney cells 293T. The luciferase activity of the cells containing the wild-type EV71 5′UTR 233–254 or VP2 1234–1256 reporter plasmid was significantly suppressed in the presence of the exogenous let-7a compared with the negative control (mimic NC). In contrast, the luciferase activity of the cells containing the mutant EV71 5′UTR or VP2 reporter plasmid showed no difference between let-7a and the mimic NC group (Figure 3A,B). These data confirmed that let-7a could specifically bind and target the EV71 genome at the predicted 5′UTR 233–254 and VP2 1234–1256 regions.

Figure 3.

Let-7a specifically targeted 5′UTR and VP2 sequences of EV71. The predicted let-7a targeted EV71 sequences, 5′UTR 233–254 and VP2 1234–1256, and their mutants were cloned into the pMIR™ reporter plasmid. The reporter plasmid was then co-transfected with 200 nM let-7a into the HEK 293T cells. The luciferase activity of the reporter plasmid was evaluated at 24 h post-transfection. The suppressive effect and specificity of let-7a on 5′UTR sequence 233–254 (A) and VP2 sequence 1234–1256 (B) are shown. The seed sequence of let-7a is depicted in a blue color. The mutated nucleotides on the viral targeted sequences are shown in a red color. The pairing nucleotides between let-7a and the viral sequences are underlined. The negative control of miRNA is a scrambled sequence of let-7a (NC). Mean ± SD, *: p < 0.05.

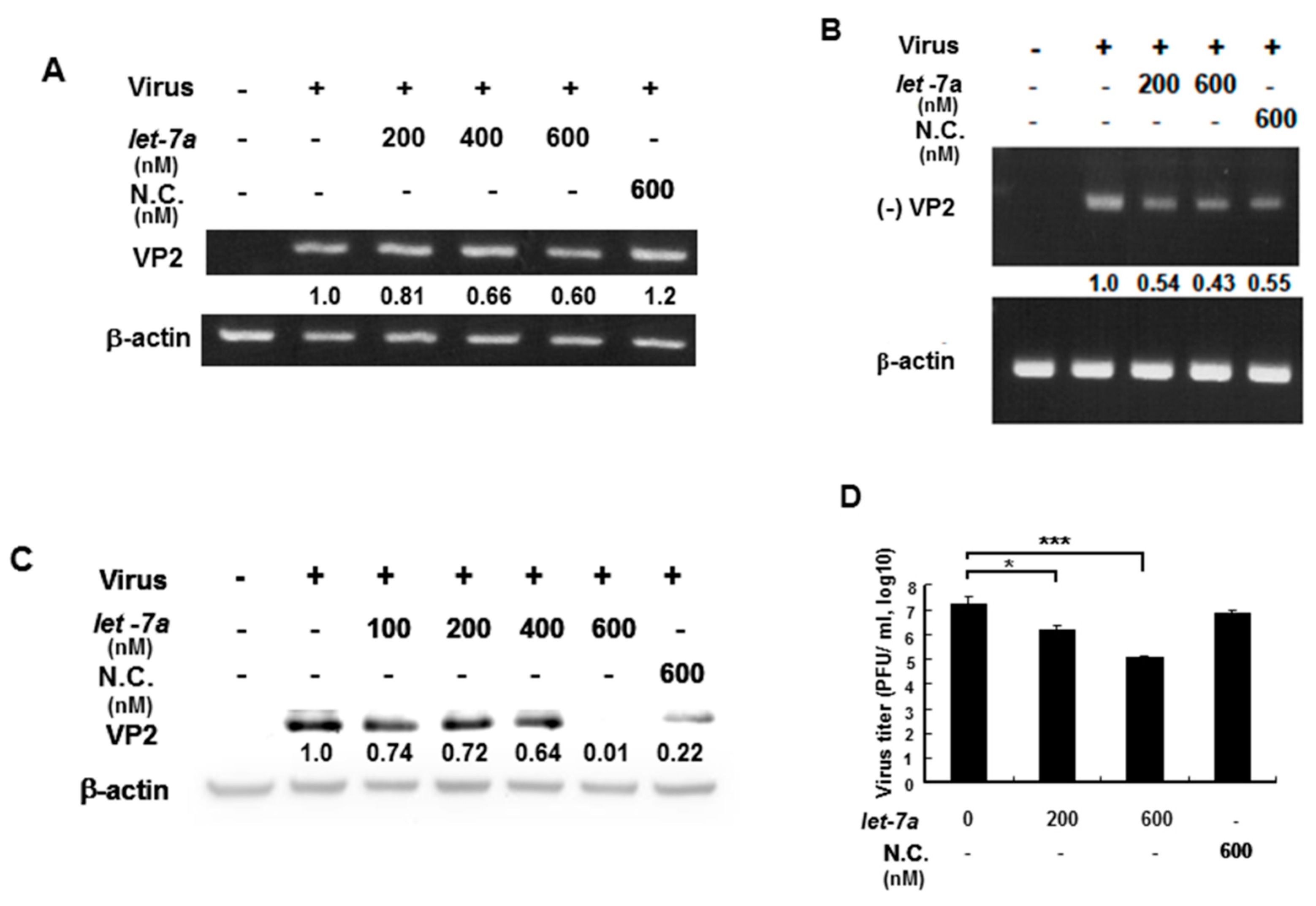

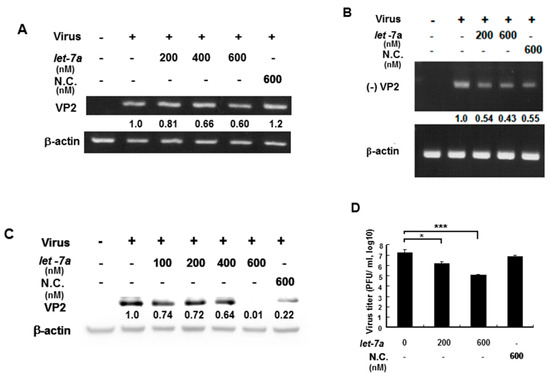

3.5. Let-7a Suppressed EV71 RNA Expression and Viral Titer in Various Infected Cell Lines

EV71 contains a (+) single-stranded RNA genome, which is translated into a single polyprotein followed by proteolytically processing into mature single gene products. VP2 gene RNA and protein expression levels were measured by RT-PCR and Western blotting because let-7a specifically targets VP2 sequences so this was used to as an indicator to represent whether let-7a could suppress EV71 RNA and protein expression. An EV71/4643 strain was used to infect human muscle rhabdomyosarcoma RD cells in the presence or absence of exogenous let-7a by transient transfection. Our data showed that let-7a significantly decreased the levels of both the (+) stranded and (−) stranded RNA expression of the EV71 in a dose-dependent manner compared with infected cells without a let-7a transient transfection (Figure 4A,B). Similarly, let-7a inhibited the EV71 VP2 protein expression in the infected cells dose-dependently compared with the infected cells without a let-7a transient transfection (Figure 4C). Notably, a high concentration (600 nM) of non-specific scramble miRNA (NC) could also suppress viral (−) strained RNA and VP2 protein expression (Figure 4B,C) indicating that the non-specific scramble miRNA (NC) might target the viral (-) strained RNA and lead to the suppression of VP2 protein expression. Nevertheless, let-7a (600 nM) showed a much higher suppressive effect on VP2 protein expression (Figure 4C, lane 6 vs. lane 7). It indicated that the overexpression of let-7a could specifically suppress the replication of both progenitor and progeny viruses. Accordingly, the viral titer of EV71 was decreased in a let-7a dose-dependent manner in the infected RD cells compared with the infected cells without let-7a or with the scramble miRNA (NC) treatment by plaque assays (Figure 4D). Likewise, the effect of this specific suppression of let-7a on EV71 viral replication was also observed in EV71-infected neuronal SK-N-SH cells (Supplementary Figure S1). In summary, let-7a specifically suppressed EV71 RNA and protein expression and inhibited EV71 viral replication in various infected cells.

Figure 4.

Let-7a suppressed EV71/4643 replication in infected RD cells. RD cells were transformed with let-7a for 24 hr before infection with EV71/4643 (MOI = 10) for 9 hr. (A) The suppression of let-7a at various concentrations on the viral RNA expression was evaluated by RT-PCR using the primers against (+) VP2 sequences. NC was the scramble control microRNA. The β-actin gene was used as the control. (B) The suppression of let-7a on negative-strand viral RNA expression (designated as (−) VP2) was evaluated by RT-PCR using the primers against (-) VP2 sequences. The negative control (NC) was the scramble control microRNA. The β-actin gene was used as the control. (C) Let-7a suppression of VP2 protein levels in viral-infected cells was determined by Western blotting using specific antibodies. β-actin was used as the internal control. (D) RD cells were transfected with let-7a or NC microRNA at various concentrations for 24 hr followed by infection with EV71/4643 (MOI = 10) for 1 hr. The virus titer was determined by plaque assay. Mean ± SD, *: p < 0.05, ***: p < 0.001.

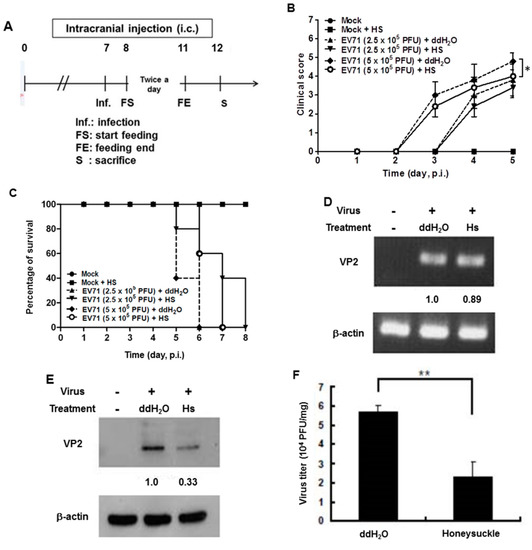

3.6. Honeysuckle Ingestion Attenuated Disease Symptoms, Prolonged Survival Time and Suppressed Viral Replication as Well as Viral Titer in EV71 MP4-Infected Suckling Mice

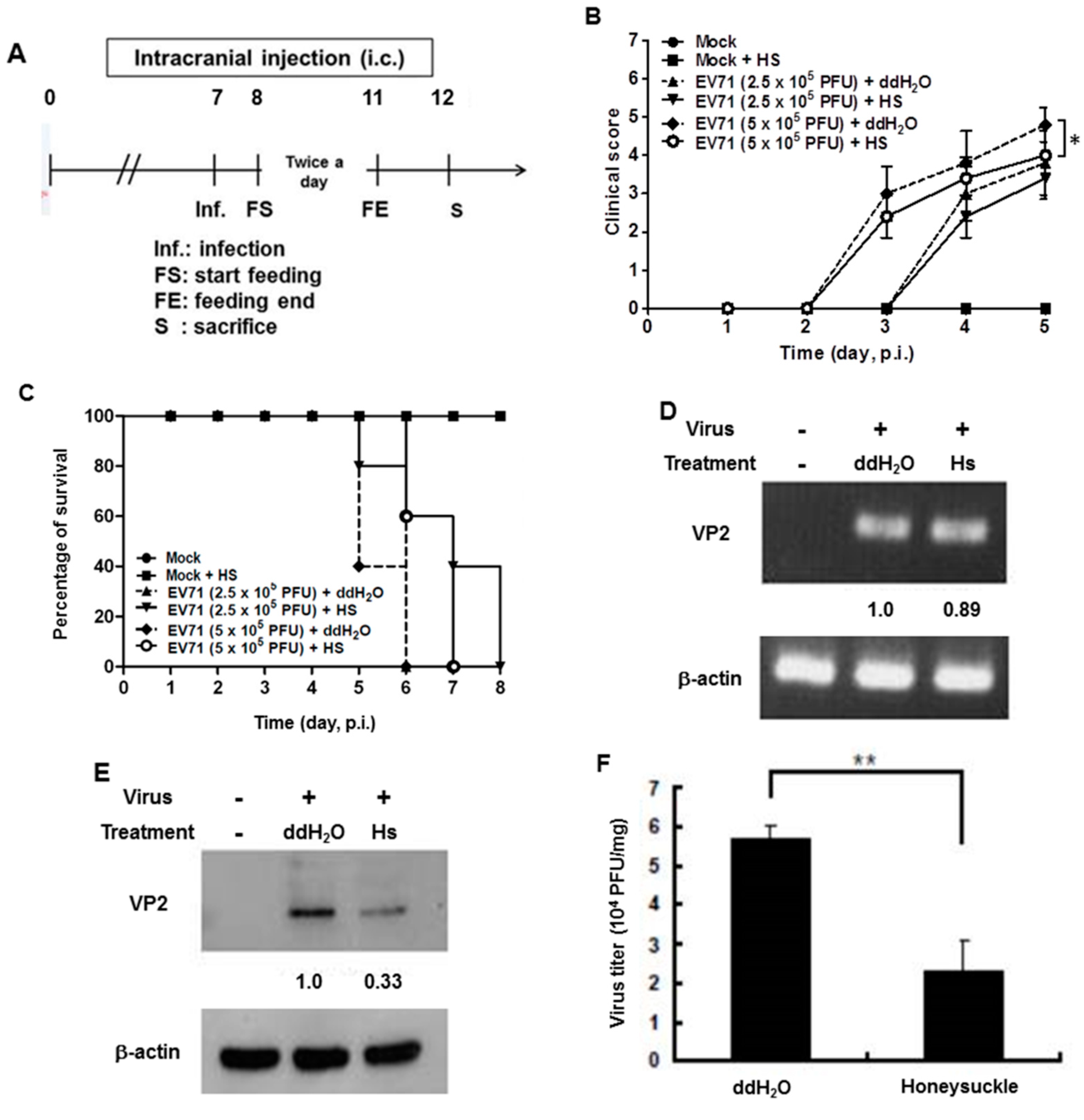

We previously reported that the let-7a expression level was strongly induced in the blood of 7-day-old ICR suckling mice after the ingestion of honeysuckle aqueous extract for four days [2]. To clarify whether honeysuckle or induced let-7a could suppress EV71 replication and affect the related pathogenesis in vivo, an ICR suckling mouse model was used [2]. The suppressive effect of honeysuckle on EV71 infection was evaluated using 7-day-old ICR suckling mice after an intracranial (IC) injection of an MP4 strain of EV71 followed by the ingestion of honeysuckle aqueous extract from day 8 to day 11 (two doses a day). All of the mice were sacrificed on day 12 (Figure 5A). The clinical scores representing disease symptoms of the EV71-infected mice were measured from day 2 PI. Two doses of EV71 were used in this study (2.5 × 105 and 5 × 105 pfu). Our data disclosed that clinical scores were detected on day 3 PI and honeysuckle treatment attenuated the clinical scores of the mice, which correlated with the titer of the infected virus (Figure 5B). Furthermore, the mice infected with viruses at either 2.5 × 105 or 5 × 105 pfu died on day 6 PI. Honeysuckle ingestion prolonged the survival time of the mice infected with viruses at 5 × 105 or 2.5 × 105 pfu for one to two days. No mice died without EV71 infection regardless of whether or not they ingested honeysuckle extract (Figure 5C). All of the mice in the Mock and Mock + HS groups remained normal (clinical score = 0) and showed a 100% survival rate.

Figure 5.

Honeysuckle treatment attenuated EV71/MP4 pathogenesis in infected ICR suckling mice. The 7-day-old ICR suckling mice (n = 5, each group) were infected with either a mock infection (2% FBS in DMEM) or EV71 MP4 by intracranial injection followed by treatment with honeysuckle aqueous extract twice a day for four consecutive days. Mice that received boiled distilled water served as the Mock control. The mice were then examined for survival rate, disease symptoms and the viral gene expression and production in the brain. (A) The time schedule of suckling mice with the virus infection, honeysuckle treatment and sacrifice. (B) The mice were intracranially inoculated (IC) with two concentrations of EV71/MP4 followed by honeysuckle treatment. The clinical scores were measured from day 1 to day 5 PI. (C) The survival time of the EV71/MP4 infected mice with or without honeysuckle treatment was evaluated for eight days after infection. The virus-infected suckling mice were sacrificed at day 5 PI. Viral activities in the brain specimens were investigated. (D) The EV71/MP4 RNA level in brains was determined by RT-PCR. β-actin was used as the internal control. (E) The EV71/MP4 VP2 protein level in the infected suckling mice brains was determined by Western blotting using specific antibodies. β-actin was used as the internal control. (F) The viral titer of EV71/MP4 in the infected suckling mice brains was determined by plaque assay. HS: honeysuckle; ddH2O: double distilled water; N = the number of mice in each group. Mean ± SD, *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01. Clinical score representation: 0: healthy; 1: ruffled hair, hunchbacked or reduced mobility; 2: wasting; 3: forelimb or hindlimb weakness; 4: forelimb or hindlimb paralysis; 5: death.

We collected the brain tissues of EV71-infected mice receiving honeysuckle or ddH2O treatment at day 5 after virus inoculation and the viral RNA and protein levels as well as the virus titer were determined. We found that the viral RNA expression of EV71 was slightly decreased in the honeysuckle ingestion group (Hs) compared with the ddH2O group by RT-PCR analysis (Figure 5D). Notably, the VP2 protein expression was decreased by 67% in the honeysuckle ingestion group compared with the ddH2O group by Western blot analysis (Figure 5E). The virus titer in the brains of EV71-infected mice that ingested honeysuckle water was decreased by over 50% compared with the ddH2O group (Figure 5F). Taken together, our findings demonstrated that ingestion of honeysuckle one day after EV71 infection alleviated disease symptoms and extended the survival time of the infected suckling mice and these effects were accompanied by the suppression of EV71 replication as well as a decreased virus titer.

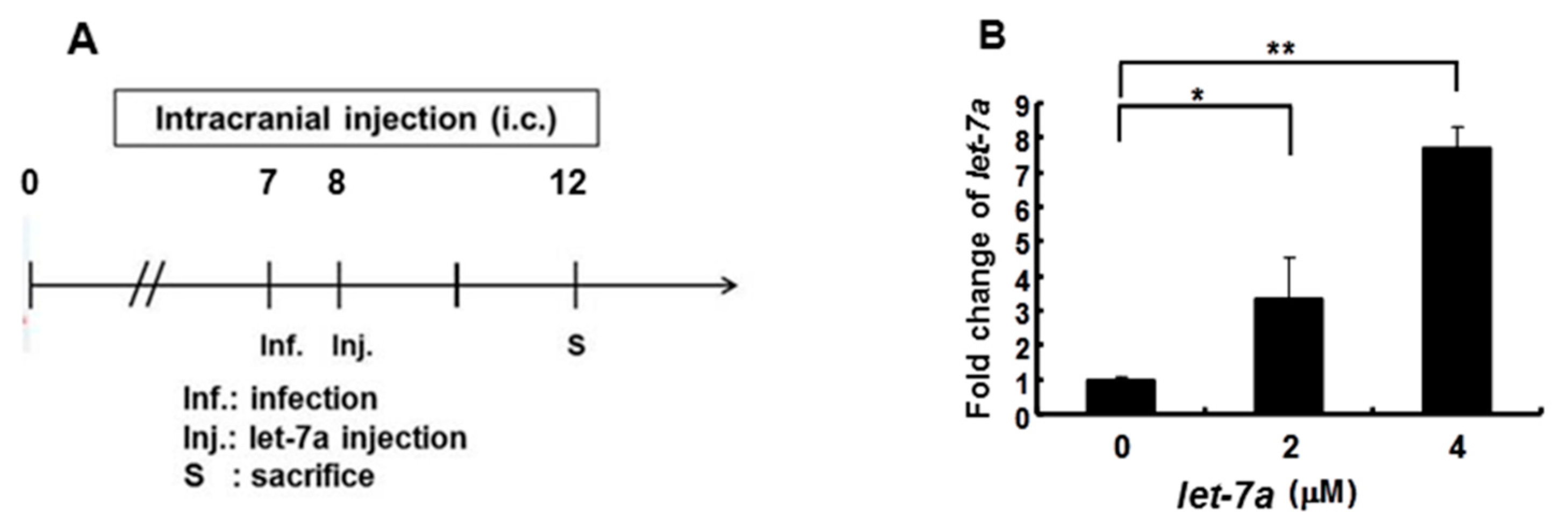

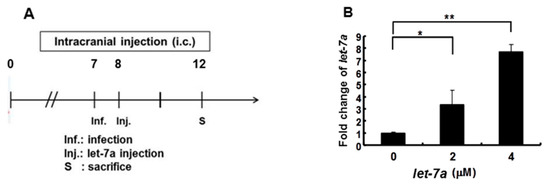

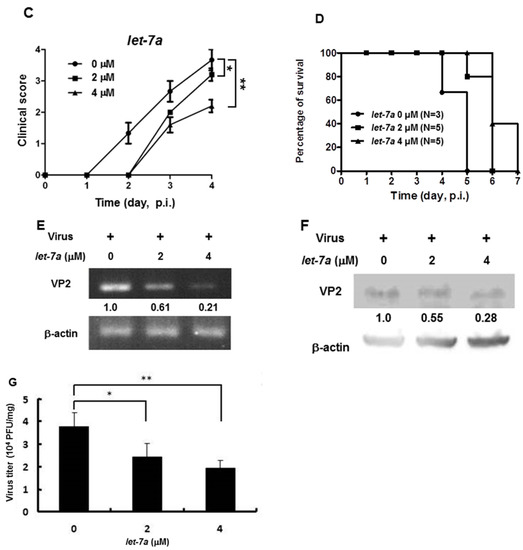

3.7. Let-7a Treatment Alleviated Clinical Scores, Prolonged Survival Time and Suppressed Viral Replication and Viral Titer in EV71 MP4-Infected Suckling Mice

As shown in Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4, we demonstrated that let-7a could specifically target EV71-5′UPR and -VP2 sequences accompanied by the suppression of EV71 replication in infected cell lines. In Figure 5, it can be seen that honeysuckle ingestion alleviated the disease symptoms and prolonged the survival time of EV71-infected ICR suckling mice. Let-7a was the most upregulated miRNA induced by the ingestion of honeysuckle as detected both in human volunteers and in mice [2,20]. Therefore, we further clarified the effects of exogenous let-7a on the clinical scores and the survival time of EV71-infected ICR suckling mice and EV71 replication. The 7-day-old ICR suckling mice shown in Figure 5 were IC inoculated with EV71 MP4 (5 × 105 pfu) at day 7 followed by an IC injection of let-7a (2 μM and 4 μM in 20 μL of DMEM) at day 8. All of the mice were sacrificed at day 12 (Figure 6A). The mice brains were sectioned and let-7a expression, virus protein, RNA and titer were measured. Our data showed that the levels of let-7a in the brains were elevated three-fold and seven-fold with a dose of 2 μM and 4 μM of let-7a, respectively (Figure 6B). Under these conditions, exogenous let-7a inoculation (2 and 4 μM) significantly attenuated the clinical scores of the EV71-infected mice on day 4 PI compared with the untreated EV71-infected mice (Figure 6C). Furthermore, let-7a inoculation at concentrations of 2μM and 4 μM prolonged the survival of the infected mice from day 5 to days 6 and 7, respectively (Figure 6D). Further studies revealed that let-7a treatment at concentrations of 2 μM and 4 μM resulted in a 39–79% reduction of viral RNA expression (Figure 6E) and a 45–72% reduction of VP2 protein expression (Figure 6F). Furthermore, inoculation with either 2 μM or 4 μM of let-7a decreased the viral titer in the brain tissues of the infected mice from 66% to 53% compared with the untreated control group (Figure 6G). In conclusion, let-7a inoculation showed a similar suppression effect on the uptake of honeysuckle including the alleviation of clinical scores and the extension of the survival time of EV71-infected mice. Furthermore, let-7a suppressed EV71 replication, leading to a decreased virus titer in the brains of the infected mice.

Figure 6.

Let-7a treatment alleviated the pathogenesis of EV71/MP4-infected ICR suckling mice. Seven-day-old ICR suckling mice were inoculated IC with EV71 MP4 (5 × 105 pfu per mouse). Indicated concentrations of let-7a were IC injected one day after virus inoculation. (A) The time schedule of the suckling mice with virus infection, let-7a injection and sacrifice. (B) Total RNA was harvested and the let-7a expression level in the brain tissues was determined by real-time PCR. (C) Clinical scores were measured daily after let-7a treatment. Mice brain tissues were collected four days after virus inoculation. (D) The EV71/MP4 VP2 protein level in the infected suckling mice brains with or without let-7a was determined by Western blotting using specific antibodies. β-actin was used as the internal control. (E) The expression level of VP2 was examined by specific primers and RT-PCR. The expression level of β-actin was used as an internal control. (F) Total protein was harvested and the expression level of the VP2 protein in the mice brain tissues was examined by Western blotting using specific antibodies. (G) The virus was harvested and the virus titer was determined by plaque assay. Mean ± SD, *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01.

4. Discussion

The disease symptoms of EV71-infected human patients were defined as stage 1: hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) and herpangina; stage 2: CNS complication; stage 3: cardiopulmonary failure and pulmonary edema; stage 4: convalescence [23]. Accordingly, the clinical scores of EV71-infected suckling mice were classified as follows: score 0: healthy; score 1: ruffled hair, hunchbacked or reduced mobility; score 2: wasting; score 3: forelimb or hindlimb weakness; score 4: forelimb or hindlimb paralysis; score 5: death (see Materials and Methods). In our suckling mouse model, all of the infected mice died at day 5 or day 6 PI (Figure 5C and Figure 6D) indicating that EV71 intracranial infection is lethal to these mice. The pathogenesis of EV71-infected patients consists of direct damage to the target cells and organs as well as virus-induced immunopathogenesis including cytokine storm, inflammation, immune injury or cross-reactivity of antibodies to brain cells as well as antibody enhancement [58,59]. In this study, we found that either honeysuckle or let-7a could suppress EV71 VP2 gene expression and replication, which led to a decreased viral load accompanied by an attenuated pathogenesis and prolonged life span of the infected mice. These findings are similar to our previous report that showed either honeysuckle or let-7a could suppress DENV replication and pathogenesis. In addition, honeysuckle ingestion showed a preventive effect against the DENV2 challenge [2].

Let-7a targeted sequences on VP2 1234–1256 corresponding to EV71 amino acid sequences 163–171 (nucleotide sequence 1232–1258: caaaatgcacagttccactacctctat; peptide sequence 163–171: QNAQFHYLY; the major targeted nucleotide/peptide sequences are highlighted in bold; designated as: VP2 let-7a a163–171). VP2 is the capsid protein of EV71. VP2 together with VP1 can interact with the host cell receptor SCARB2 to provide attachment to the targeted cells [60]. Therefore, the finding that let-7a targeted the EV71 VP2 gene and reduced its expression implied that honeysuckle suppressed EV71 replication possibly by the blockage of the viral assembly and the prevention of viral maturation through the upregulation of endogenous let-7a expression.

The EV71 5′UTR region forms six stem-loop structures (from I to VI), which play important roles in viral replication and translation [17]. Furthermore, 5′UTR stem-loops II to VI contain the internal ribosome entry site (IRES) controlling the efficiency of translation initiation and viral replication during interactions with cellular factors [17,61]. Another let-7a targeting site on the EV71 genome is located at the 5′UTR 233–254 region, which encompasses the EV71 IRES sequence [17]. EV71 viral protein synthesis and IRES activity are up- or downregulated through interaction with the EV71 stem-loop IV by host factors PTB and FBP2, respectively [17]. Furthermore, host hnRNP K binds to the EV71 stem-loop IV to enhance viral RNA replication [17]. It is possible that honeysuckle-induced let-7a may interfere with the EV71 translation and replication by altering the stem-loop structure or interrupting the interaction between the host factors and the stem-loop IV. Moreover, let-7a maturation has been reported to be negatively regulated by a cellular factor hnRNP A1 to enhance the IRES activity [62,63].

Let-7a is a highly conserved miRNA, which was initially identified in Caenorhabditis elegans [64]. It is ubiquitously expressed in diverse tissues and organs [65,66,67]. Let-7a regulates development [64] and inhibits cell proliferation through the suppression of various target genes including proto-oncogene Ras [68,69], c-Myc [70,71], high mobility group protein (HMGA2) [72,73,74], NIRF [75], E2F2 and CCND2 [76]. It inhibits cell cycle and differentiation through the activation of p21WAF1 [75] and suppresses cell migration and apoptosis by targeting integrin beta-3 and caspase-3, respectively [77,78]. Let-7a is known as a tumor suppressor. The negative regulators of let-7a biogenesis including Lin28a, Lin28b and hnRNP A1 are associated with cancer formation [62]. We previously reported that honeysuckle treatment increased let-7a levels both in vitro and in vivo, which suppressed both DENV replication and the Ras protein level of the host cells [2]. These findings implied that honeysuckle-induced let-7a not only suppressed viral infection via the targeting of viral genome sequences but also led to the attenuation of tumor development by targeting the oncogene Ras.

Moreover, honeysuckle is one of the most commonly prescribed herbs in the treatment or prevention of COVID-19 according to an extensive analysis of the frequency of TCM used in China [79]. Honeysuckle was also predicted to be effective in treating SARS-CoV-2 infection. TCM formulae containing honeysuckle such as the Honeysuckle Decoction, Lianhuaqingwen capsules and the Shuang-Huang-Lian oral solution have been used as potential candidates for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection [43]. The Honeysuckle Decoction inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication and accelerates the recovery of infected patients [80]. Lianhuaqingwen capsules significantly inhibited the replication of SARS-CoV-2 and reduced IL-6, IL-8, CCL-2/MCP-1, CXCL-10 and TNF-α [81]. The Shuang-Huang-Lian oral solution also decreased the transcriptional and translational levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 [82]. A randomized clinical trial (ChiCTR2000029822) conducted in China investigated the use of honeysuckle in the treatment of patients with COVID-19 and the results appeared to show a therapeutic benefit [80]. In addition, two reports disclosed that honeysuckle contains the small RNA designated as miRNA2911, which could specifically suppress the Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and the influenza virus [83,84]. Taken together, the above findings indicate that honeysuckle per se and upregulated host miRNAs (Figure 1) including let-7a are capable of specifically targeting DENV and EV71 as well as the notorious SARS-CoV-2 (Supplementary Table S1) based on experimental evidence and in silico predication. In addition, we have revealed that honeysuckle is a broad spectrum antiviral agent because it induces multiple miRNAs that may target various viruses.

In our study, a pathway analysis using CPDB and IPA revealed a broad spectrum of the possible antiviral activity of honeysuckle (Table 1 and Table 2). A fulminant cytokine storm is the leading cause of mortality in COVID-19-induced ARDS [85]. Our analysis showed honeysuckle participated in the regulation of the majority of cytokines such as IL-2, IL-7 and TNF-α [32]. The miRNAs corresponding to the biological pathways of honeysuckle could be discovered using the “g:Profiler”-linked miRTarBase. The novel findings presented herein warrant further and more rigorous clinical trials to validate the use of honeysuckle in treating and preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection.

MiRNAs play multiple functions under different conditions. Thus, in order to develop a drug capable of inducing endogenous miRNAs that can target the viral genome and inhibit viral replication, we also need to consider its side effects on the host. Some miRNAs show a suppressive effect on viral replication but are also toxic to the host when they are highly expressed. In comparison, other naturally occurring products capable of suppressing EV71 activity may have stronger side effects in patients such as the famously toxic plant Daphne Genkwa that may cause circulatory arrest and internal bleeding [86] or Rheum palmatum that induces gastroenteritis and diarrhea [87,88]. Honeysuckle is a traditional herb that has long been used to treat diverse diseases including flu-like symptoms in China and is not known to induce any side effects. Nonetheless, further research is needed to establish the toxicity of honeysuckle extract in human subjects.

Our data showed that honeysuckle induced multiple innate miRNAs that might target SARS-CoV-2 and DENV2 as well as EV71 simultaneously (Supplementary Table S1). Furthermore, these miRNAs may recognize the viral genomes at multiple regions (Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, honeysuckle offers a unique advantage in that it can prevent drug resistance caused by viral RNA sequence mutation, a phenomenon seen with many antiviral drugs, by targeting multiple regions of the viral genome. Various active ingredients extracted from the honeysuckle plant have been reported to exhibit antimicrobial activities; however, the functional component in honeysuckle responsible for let-7a overexpression and its anti-EV71 activity remains incompletely understood. Furthermore, we cannot exclude the possibility that honeysuckle ingestion increased innate immunity through up-regulation of let-7a together with other active ingredients that may have contributed to the suppression of viral replication (SARS-CoV-2, DENV-2 and EV71) in the infected mice. Given that EV71 can evade human immune surveillance [21] and that vaccination may cause EV71-associated antibody enhancement, our promising findings may be of value in the development of a novel anti-EV71 treatment in combination with other symptom-relieving drugs. Most importantly, there is an urgent need to confirm that the modulation of the innate miRNA system using honeysuckle could contribute to the suppression of SARS-CoV-2.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4915/13/2/308/s1, Figure S1: Overexpressed let-7a in infected SK-N-SH cells inhibited EV71 replication, Table S1: The prediction of miRNA-§targeted sequences in SARS-CoV-2, DENV2 and EV71 genomes. Table S2: The sequence alignments of let-7a targeted EV71-5′UTR, VP2 and VP4 in various EV71 genomes.

Author Contributions

Y.-R.L. contributed to the design of the work, literature search, interpretation of the data, drafting and revising the work and final approval of the manuscript. C.-M.C. contributed to the literature search, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the work and final approval of the manuscript. Y.-C.Y. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting and revising the work and final approval of the manuscript. C.-Y.F.H. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data, drafting the work and final approval of the manuscript. F.-M.L. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data and final approval of the manuscript. J.-T.H. contributed to the acquisition of the data and final approval of the manuscript. C.-C.H. contributed to the conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of the data and final approval of the manuscript. J.-R.W. contributed to the conception and design of the work and final approval of the manuscript. H.-S.L. contributed to the conception and design of the work, literature search and interpretation of the data, drafting and revising the work and final approval of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Science Council of Taiwan (NSC 101-2314-B-705-003-MY3), Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 109-2314-B-705-001 and MOST 109-2327-B-010-005), Chiayi Christian Hospital, Chaiyi, Taiwan and Kaohsiung Medical University Research Center (KMU-TC108A04-0 and KMU-TC108A04-2), Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Human subject assessment was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and this study was specifically approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of National Cheng Kung University Hospital (IRB approval number IBR-99-127, 1 May 2019). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Animal welfare and experimental studies complied with the guidelines of the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996) and this study was specifically approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Model Animal Research Center (MARC) of Nanjing University and the IACUC of National Cheng Kung University (approval number No. 101291).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are already provided in the manuscript at the required section. There are no underlying data available.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lingling Yu (BGI), Yaping Zhang and Zhen Bian (NJU) for their technical support. We thank Cheng-Tao Wu, Maobin Dn (IBJPCAS), Guanghai Liu (LHI), Faqiang Wang (LJP Co), Fenyong Liu (UC Berkeley) and members of the State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology (NJU) for their assistance in data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Shang, X.; Pan, H.; Li, M.; Miao, X.; Ding, H. Lonicera japonica thunb.: Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology of an important traditional chinese medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 138, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.R.; Yeh, S.F.; Ruan, X.M.; Zhang, H.; Hsu, S.D.; Huang, H.D.; Hsieh, C.C.; Lin, Y.S.; Yeh, T.M.; Liu, H.S.; et al. Honeysuckle aqueous extract and induced let-7a suppress dengue virus type 2 replication and pathogenesis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017, 198, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baulcombe, D. Rna silencing in plants. Nature 2004, 431, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, E.J.; Carrington, J.C. Specialization and evolution of endogenous small rna pathways. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 884–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefani, G.; Slack, F.J. Small non-coding rnas in animal development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.F.; Liston, A. Microrna in the immune system, microrna as an immune system. Immunology 2009, 127, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaria, V.; Hariharan, M.; Maiti, S.; Pillai, B.; Brahmachari, S.K. Host-virus interaction: A new role for micrornas. Retrovirology 2006, 3, 68. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, P.W.; Lin, L.Z.; Hsu, S.D.; Hsu, J.B.; Huang, H.D. Vita: Prediction of host micrornas targets on viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, D381–D385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, J.K.; Khan, S.Z.; Soni, K.; Rawat, P.; Gupta, A.; Hariharan, M.; Scaria, V.; Lalwani, M.; Pillai, B.; Mitra, D.; et al. Human cellular microrna hsa-mir-29a interferes with viral nef protein expression and hiv-1 replication. Retrovirology 2008, 5, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breving, K.; Esquela-Kerscher, A. The complexities of microrna regulation: Mirandering around the rules. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 1316–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesla, M.; Skrzypek, K.; Kozakowska, M.; Loboda, A.; Jozkowicz, A.; Dulak, J. Micrornas as biomarkers of disease onset. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011, 401, 2051–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajit, S.K. Circulating micrornas as biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and signaling molecules. Sensors 2012, 12, 3359–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kren, B.T.; Wong, P.Y.; Sarver, A.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, Y.; Steer, C.J. Micrornas identified in highly purified liver-derived mitochondria may play a role in apoptosis. RNA Biol. 2009, 6, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valadi, H.; Ekstrom, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjostrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lotvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mrnas and micrornas is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Qian, Y.; Wang, S.; Serrano, J.M.; Li, W.; Huang, Z.; Lu, S. Ev71: An emerging infectious disease vaccine target in the far east? Vaccine 2010, 28, 3516–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.L.; Chiang, P.S.; Chia, M.Y.; Luo, S.T.; Chang, L.Y.; Lin, T.Y.; Ho, M.S.; Lee, M.S. Cross-reactive neutralizing antibody responses to enterovirus 71 infections in young children: Implications for vaccine development. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, S.R.; Stollar, V.; Li, M.L. Host factors in enterovirus 71 replication. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 9658–9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMinn, P.C. Recent advances in the molecular epidemiology and control of human enterovirus 71 infection. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012, 2, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, T.; Lewthwaite, P.; Perera, D.; Cardosa, M.J.; McMinn, P.; Ooi, M.H. Virology, epidemiology, pathogenesis, and control of enterovirus 71. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 778–790. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, X.; Ku, Z.; Wang, T.; Liu, F.; Cai, Y.; Li, D.; Leng, Q.; Huang, Z. Characterization of enterovirus 71 capsids using subunit protein-specific polyclonal antibodies. J. Virol. Methods 2013, 187, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denizot, M.; Neal, J.W.; Gasque, P. Encephalitis due to emerging viruses: Cns innate immunity and potential therapeutic targets. J. Infect. 2012, 65, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fowlkes, A.L.; Honarmand, S.; Glaser, C.; Yagi, S.; Schnurr, D.; Oberste, M.S.; Anderson, L.; Pallansch, M.A.; Khetsuriani, N. Enterovirus-associated encephalitis in the california encephalitis project, 1998–2005. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 198, 1685–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.Y. Enterovirus 71 in taiwan. Pediatrics Neonatol. 2008, 49, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.I.; Weng, K.F.; Shih, S.R. Viral and host factors that contribute to pathogenicity of enterovirus 71. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, K.F.; Chen, L.L.; Huang, P.N.; Shih, S.R. Neural pathogenesis of enterovirus 71 infection. Microbes Infect. 2010, 12, 505–510. [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi, T.; Fujisawa, H.; Sakai, K.; Okino, S.; Kurosaki, N.; Nishimura, Y.; Shimizu, H.; Yamada, M. Acute encephalitis caused by intrafamilial transmission of enterovirus 71 in adult. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 828–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatproedprai, S.; Theanboonlers, A.; Korkong, S.; Thongmee, C.; Wananukul, S.; Poovorawan, Y. Clinical and molecular characterization of hand-foot-and-mouth disease in thailand, 2008–2009. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 63, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Horby, P.W.; Hayden, F.G.; Gao, G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020, 395, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Niu, P.; Yang, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Huang, B.; Zhu, N.; et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020, 395, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, W.; Farzan, M.; Harrison, S.C. Structure of sars coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science 2005, 309, 1864–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Q.; Yang, K.; Wang, W.; Jiang, L.; Song, J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to covid-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from wuhan, china. Intensive Care Med 2020, 46, 846–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in wuhan, china. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.D.; Millar, J.E.; Baillie, J.K. Clinical evidence does not support corticosteroid treatment for 2019-ncov lung injury. Lancet 2020, 395, 473–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Kruger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. Sars-cov-2 cell entry depends on ace2 and tmprss2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupferschmidt, K.; Cohen, J. Race to find covid-19 treatments accelerates. Science 2020, 367, 1412–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Z.; Zhu, R.; Hou, W.; Feng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Han, Q.; Shan, G.; Meng, F.; Du, D.; Wang, S.; et al. Transplantation of ace2(-) mesenchymal stem cells improves the outcome of patients with covid-19 pneumonia. Aging Dis. 2020, 11, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerstein, R.; Kochen, M.M.; Messerli, F.H.; Grani, C. Coronavirus disease 2019 (covid-19): Do angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers have a biphasic effect? J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koniari, I.; Kounis, N.G. Cardiac arrest caused by nafamostat mesilate: Kounis syndrome in the dialysis room? Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 36, 105–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokkermans, T.J.; Trichonas, G. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine toxicity. In Statpearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; Zeng, L.; Li, R.; Chen, Q.; Zhou, B.; Chen, Q.; Cheng, P.L.; Yutao, W.; Zheng, J.; Yang, Z.; et al. The chinese prescription lianhuaqingwen capsule exerts anti-influenza activity through the inhibition of viral propagation and impacts immune function. BMC Complement Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, P.M.; Wong, C.K.; Fung, K.P.; Fong, C.Y.; Wong, E.L.; Lau, J.T.; Leung, P.C.; Tsui, S.K.; Wan, D.C.; Waye, M.M.; et al. Immunomodulatory effects of a traditional chinese medicine with potential antiviral activity: A self-control study. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2006, 34, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.T.; Leung, P.C.; Wong, E.L.; Fong, C.; Cheng, K.F.; Zhang, S.C.; Lam, C.W.; Wong, V.; Choy, K.M.; Ko, W.M. The use of an herbal formula by hospital care workers during the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic in hong kong to prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome transmission, relieve influenza-related symptoms, and improve quality of life: A prospective cohort study. J. Altern. Complement Med. 2005, 11, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Islam, M.S.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, X. Traditional chinese medicine in the treatment of patients infected with 2019-new coronavirus (sars-cov-2): A review and perspective. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Garner, L.V.; Watkins, S.P.; Carter, L.J.; Smoot, J.; Gregg, A.C.; Daniels, A.D.; Jervey, S.; et al. Research and development on therapeutic agents and vaccines for covid-19 and related human coronavirus diseases. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C. Coronavirus puts drug repurposing on the fast track. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 379–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozomara, A.; Griffiths-Jones, S. Mirbase: Integrating microrna annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D152–D157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yang, K.; Fang, S.; Bu, D.; Li, H.; Sun, L.; Hu, H.; Gao, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Symmap: An integrative database of traditional chinese medicine enhanced by symptom mapping. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D1110–D1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, C.H.; Shrestha, S.; Yang, C.D.; Chang, N.W.; Lin, Y.L.; Liao, K.W.; Huang, W.C.; Sun, T.H.; Tu, S.J.; Lee, W.H.; et al. Mirtarbase update 2018: A resource for experimentally validated microrna-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D296–D302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudvere, U.; Kolberg, L.; Kuzmin, I.; Arak, T.; Adler, P.; Peterson, H.; Vilo, J. G:Profiler: A web server for functional enrichment analysis and conversions of gene lists (2019 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W191–W198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamburov, A.; Stelzl, U.; Lehrach, H.; Herwig, R. The consensuspathdb interaction database: 2013 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D793–D800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Green, J.; Pollard, J., Jr.; Tugendreich, S. Causal analysis approaches in ingenuity pathway analysis. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Chou, C.T.; Lei, H.Y.; Liu, C.C.; Wang, S.M.; Yan, J.J.; Su, I.J.; Wang, J.R.; Yeh, T.M.; Chen, S.H.; et al. A mouse-adapted enterovirus 71 strain causes neurological disease in mice after oral infection. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 7916–7924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.W.; Wang, Y.F.; Yu, C.K.; Su, I.J.; Wang, J.R. Mutations in vp2 and vp1 capsid proteins increase infectivity and mouse lethality of enterovirus 71 by virus binding and rna accumulation enhancement. Virology 2012, 422, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.R.; Wang, P.S.; Wang, J.R.; Liu, H.S. Enterovirus 71-induced autophagy increases viral replication and pathogenesis in a suckling mouse model. J. Biomed. Sci. 2014, 21, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, Y.H.; Huang, S.W.; Kuo, P.H.; Kiang, D.; Ho, M.S.; Liu, C.C.; Yu, C.K.; Su, I.J.; Wang, J.R. Introduction of a strong temperature-sensitive phenotype into enterovirus 71 by altering an amino acid of virus 3d polymerase. Virology 2010, 396, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.R.; Tuan, Y.C.; Tsai, H.P.; Yan, J.J.; Liu, C.C.; Su, I.J. Change of major genotype of enterovirus 71 in outbreaks of hand-foot-and-mouth disease in taiwan between 1998 and 2000. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2002, 40, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Poh, C.L.; Chow, V.T. Complete sequence analyses of enterovirus 71 strains from fatal and non-fatal cases of the hand, foot and mouth disease outbreak in singapore (2000). Microbiol. Immunol. 2002, 46, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.H.; Ong, K.C.; Wong, K.T. Enterovirus 71 can directly infect the brainstem via cranial nerves and infection can be ameliorated by passive immunization. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2014, 73, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.M.; Chen, I.C.; Su, L.Y.; Huang, K.J.; Lei, H.Y.; Liu, C.C. Enterovirus 71 infection of monocytes with antibody-dependent enhancement. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2010, 17, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.M.; Leong, K.L.; Ng, M.M.; Chu, J.J. The essential role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in the infectious entry of human enterovirus 71. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 309–321. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.Y.; Shih, S.R.; Pan, M.; Li, C.; Lue, C.F.; Stollar, V.; Li, M.L. Hnrnp a1 interacts with the 5′ untranslated regions of enterovirus 71 and sindbis virus rna and is required for viral replication. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 6106–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michlewski, G.; Caceres, J.F. Antagonistic role of hnrnp a1 and ksrp in the regulation of let-7a biogenesis. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vito, C.; Riggi, N.; Suva, M.L.; Janiszewska, M.; Horlbeck, J.; Baumer, K.; Provero, P.; Stamenkovic, I. Let-7a is a direct ews-fli-1 target implicated in ewing’s sarcoma development. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhart, B.J.; Slack, F.J.; Basson, M.; Pasquinelli, A.E.; Bettinger, J.C.; Rougvie, A.E.; Horvitz, H.R.; Ruvkun, G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 rna regulates developmental timing in caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 2000, 403, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, A.E.; Reinhart, B.J.; Slack, F.; Martindale, M.Q.; Kuroda, M.I.; Maller, B.; Hayward, D.C.; Ball, E.E.; Degnan, B.; Muller, P.; et al. Conservation of the sequence and temporal expression of let-7 heterochronic regulatory rna. Nature 2000, 408, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagos-Quintana, M.; Rauhut, R.; Yalcin, A.; Meyer, J.; Lendeckel, W.; Tuschl, T. Identification of tissue-specific micrornas from mouse. Curr. Biol. 2002, 12, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempere, L.F.; Freemantle, S.; Pitha-Rowe, I.; Moss, E.; Dmitrovsky, E.; Ambros, V. Expression profiling of mammalian micrornas uncovers a subset of brain-expressed micrornas with possible roles in murine and human neuronal differentiation. Genome Biol. 2004, 5, R13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.M.; Grosshans, H.; Shingara, J.; Byrom, M.; Jarvis, R.; Cheng, A.; Labourier, E.; Reinert, K.L.; Brown, D.; Slack, F.J. Ras is regulated by the let-7 microrna family. Cell 2005, 120, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akao, Y.; Nakagawa, Y.; Naoe, T. Let-7 microrna functions as a potential growth suppressor in human colon cancer cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 29, 903–906. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, V.B.; Rong, N.H.; Han, J.; Yang, Q.; Aris, V.; Soteropoulos, P.; Petrelli, N.J.; Dunn, S.P.; Krueger, L.J. Microrna let-7a down-regulates myc and reverts myc-induced growth in burkitt lymphoma cells. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 9762–9770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Y.; Chen, J.X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C.L.; Peng, Q.L.; Peng, H.M. The let-7a microrna protects from growth of lung carcinoma by suppression of k-ras and c-myc in nude mice. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2010, 136, 1023–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.S.; Dutta, A. The tumor suppressor microrna let-7 represses the hmga2 oncogene. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 1025–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoyama, K.; Inoue, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Uetake, H.; Sugihara, K.; Mori, M. Clinical significance of high mobility group a2 in human gastric cancer and its relationship to let-7 microrna family. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 2334–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Fu, M.; Bookout, A.L.; Kliewer, S.A.; Mangelsdorf, D.J. Microrna let-7 regulates 3t3-l1 adipogenesis. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009, 23, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Duan, C.; Chen, J.; Ou-Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, C.; Peng, H. Let-7a elevates p21(waf1) levels by targeting of nirf and suppresses the growth of a549 lung cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583, 3501–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Q.; Meng, P.; Wang, T.; Qin, W.; Qin, W.; Wang, F.; Yuan, J.; Chen, Z.; Yang, A.; Wang, H. Microrna let-7a inhibits proliferation of human prostate cancer cells in vitro and in vivo by targeting e2f2 and ccnd2. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, D.W.; Bosserhoff, A.K. Integrin beta 3 expression is regulated by let-7a mirna in malignant melanoma. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6698–6706. [Google Scholar]

- Tsang, W.P.; Kwok, T.T. Let-7a microrna suppresses therapeutics-induced cancer cell death by targeting caspase-3. Apoptosis Int. J. Program. Cell Death 2008, 13, 1215–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, H.; Tang, Q.L.; Shang, Y.X.; Liang, S.B.; Yang, M.; Robinson, N.; Liu, J.P. Can chinese medicine be used for prevention of corona virus disease 2019 (covid-19)? A review of historical classics, research evidence and current prevention programs. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 26, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.K.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, X.M.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, X.; Fu, Z.; Xiao, G.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zhang, L.K.; Yi, Y. Absorbed plant mir2911 in honeysuckle decoction inhibits sars-cov-2 replication and accelerates the negative conversion of infected patients. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Runfeng, L.; Yunlong, H.; Jicheng, H.; Weiqi, P.; Qinhai, M.; Yongxia, S.; Chufang, L.; Jin, Z.; Zhenhua, J.; Haiming, J.; et al. Lianhuaqingwen exerts anti-viral and anti-inflammatory activity against novel coronavirus (sars-cov-2). Pharm. Res. 2020, 104761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Fang, L.; Cai, R.; Zong, C.; Chen, X.; Lu, J.; Qi, Y. Shuang-huang-lian exerts anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative activities in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated murine alveolar macrophages. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, H.; Sun, X.; Ding, M.; Tao, G.; Li, X. Honeysuckle-derived microrna2911 directly inhibits varicella-zoster virus replication by targeting ie62 gene. J. Neurovirol. 2019, 25, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Dong, L.; Chen, Q.; Liu, J.; Kong, H.; Zhang, Q.; Qi, X.; Hou, D.; et al. Honeysuckle-encoded atypical microrna2911 directly targets influenza a viruses. Cell Res. 2015, 25, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.; McAuley, D.F.; Brown, M.; Sanchez, E.; Tattersall, R.S.; Manson, J.J.; Hlh Across Speciality Collaboration, U.K. Covid-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020, 395, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshiashvili, G.; Tabatadze, N.; Mshvildadze, V. The genus daphne: A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. Fitoterapia 2020, 143, 104540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, T.; Zhang, L.Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, F.M.; Zhang, Y.H.; Yu, J.H. Rheum emodin inhibits enterovirus 71 viral replication and affects the host cell cycle environment. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2017, 38, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Tao, L.; Xu, H. Chinese herbal medicines as a source of molecules with anti-enterovirus 71 activity. Chin. Med. 2016, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).