Abstract

The emergence of arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) as linked to land-use changes, especially the growing agricultural intensification and expansion efforts in rural parts of Africa, is of growing health concern. This places an additional burden on health systems as drugs, vaccines, and effective vector-control measures against arboviruses and their vectors remain lacking. An integrated One Health approach holds potential in the control and prevention of arboviruses. Land-use changes favour invasion by invasive alien plants (IAPs) and investigating their impact on mosquito populations may offer a new dimension to our understanding of arbovirus emergence. Of prime importance to understand is how IAPs influence mosquito life-history traits and how this may affect transmission of arboviruses to mammalian hosts, questions that we are exploring in this review. Potential effects of IAPs may be significant, including supporting the proliferation of immature and adult stages of mosquito vectors, providing additional nutrition and suitable microhabitats, and a possible interaction between ingested secondary plant metabolites and arboviruses. We conclude that aspects of vector biology are differentially affected by individual IAPs and that while some plants may have the potential to indirectly increase the risk of transmission of certain arboviruses by their direct interaction with the vectors, the reverse holds for other IAPs. In addition, we highlight priority research areas to improve our understanding of the potential health impacts of IAPs.

1. Introduction

Large-scale land-use changes, especially as a result of a drive towards agricultural intensification and expansion, are progressively re-shaping the future of rural Africa. The prime driver of this change remains the need to improve food security given the high population growth on the continent, leading to an estimated doubling of the population by 2050 [1]. Agricultural practices in Africa may have unintended health implications by driving the emergence of arthropod borne diseases [2]. Many important zoonotic diseases caused by arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) like Rift valley fever (RVF), West Nile, dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, and Zika originated in Africa, and their initial emergence might have remained unnoticed as human encroachment into natural ecosystems, deforestation, and agricultural transformation was taking place. Yet, the arthropod vectors that transmit these arboviruses are particularly sensitive to land-use changes [3,4,5] and can quickly adapt to changing ecosystems by altering key aspects of their bionomics.

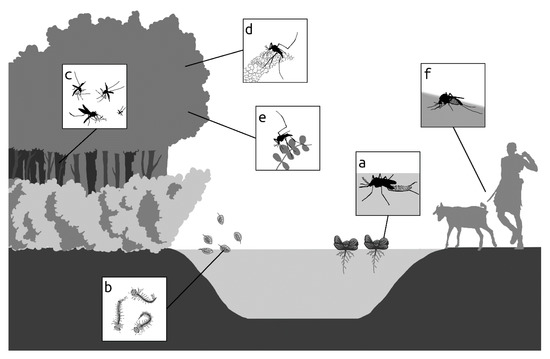

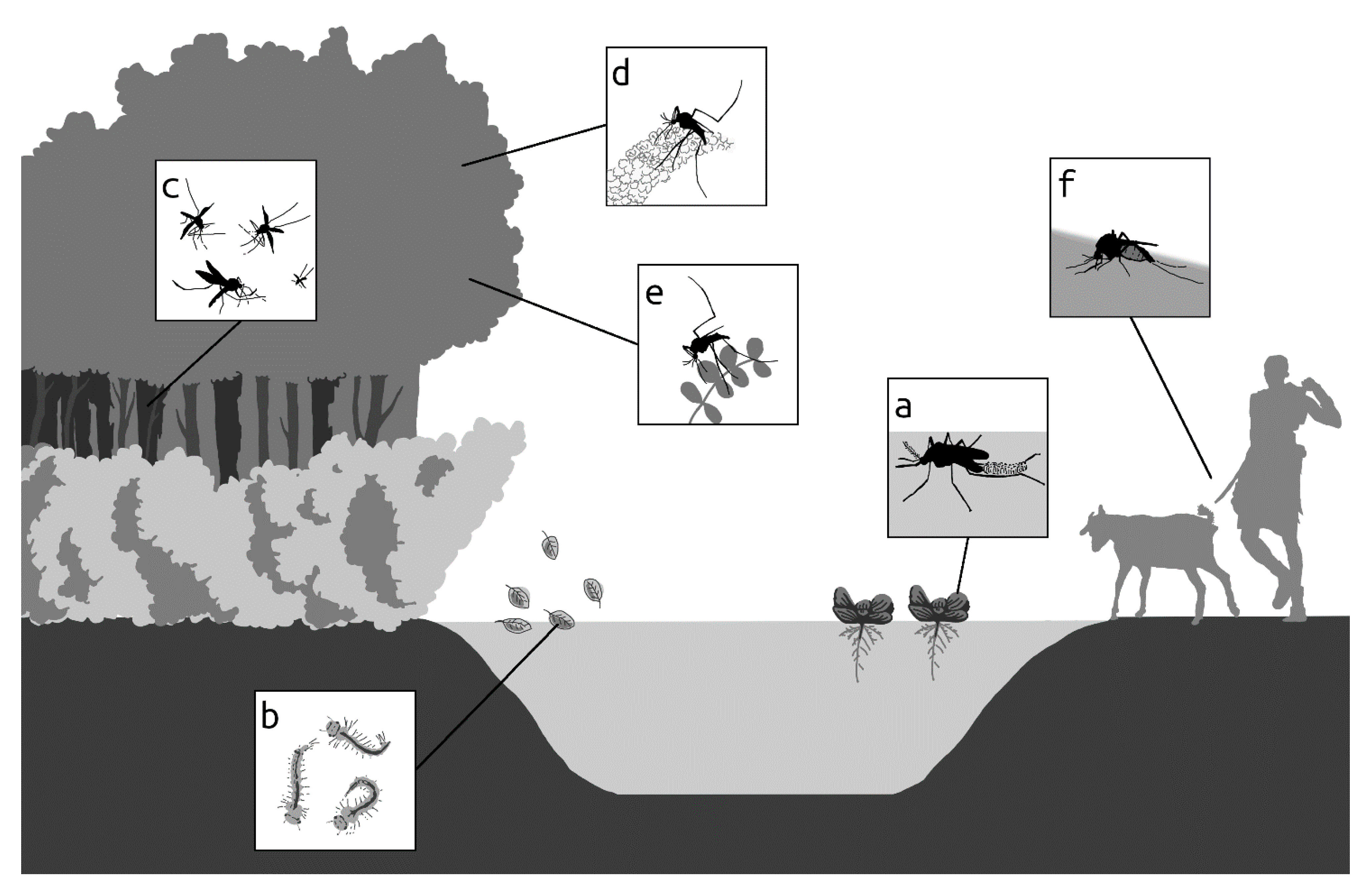

The emergence of previously unknown viruses and the re-emergence of known ones are a huge challenge to both the human and veterinary health sectors as the outbreaks they cause remain hard to predict and difficult to combat. Though an integrated One Health approach, which combines human, animal, and environmental health, could contribute in controlling arboviral diseases and in curbing their emergence and spread, these efforts are presently hampered by a lack of knowledge on the functional environmental linkages that can serve as a proxy to predicting arbovirus emergence. Moreover, certain aspects of the biology and ecology of arboviral vectors remain poorly understood, especially in the case of mosquitoes; chief amongst the less appreciated aspects of their biology is the role of plants in the feeding and survival of female members of the population. Though both male and female mosquitoes repeatedly ingest sugars available in plants to sustain daily metabolic activities, thus ensuring survival and flight [6,7], evidence increasingly suggests that female mosquitoes also depend on certain plants in the environment for different aspects of their bionomics. This may be for (i) enhancing their reproductive success [8,9], (ii) use as microhabitats [10], (iii) use for the proliferation of larvae [11,12], and (iv) for blocking transmission of pathogens [13]. These aspects of mosquito biology would potentially be affected by changes in the vegetation structure and composition. Strong differences of mosquito abundance [14,15] and survival [8,9,16] have been observed between habitats colonized by nectar-rich and nectar-poor plants. Whether invasive alien plants (IAPs) might affect the risk of emergence of malaria was recently reviewed by Stone et al. [7], but little is known on possible linkages between IAPs and life-history traits of arboviral vectors, in particular of mosquito vectors. Lately some IAPs are reported to affect the health of humans and livestock, thus adding to their already considerable economic and environmental effects [17,18,19].

In this review, we explore how vector bionomics and competence (i.e., the ability to transmit viruses) are affected by IAPs on the African environment. We focus on mosquitoes because these are the principal vectors of most arboviruses, and their biology and ecology are best understood. However, because of the limited existing knowledge on arboviral mosquito vectors we also refer to data from malaria and its mosquito vectors and explore how this knowledge can inform future research on arboviral diseases. The latter forms the second major objective of this review as we seek to identify areas where more research efforts are needed to develop a framework for future research in arbovirology. Critical evaluations will be made on individual IAPs and mosquito vector species, along the life-history of the latter, and where possible information will be provided on the inhibiting potential of IAPs against arboviruses. Exploring the link between IAPs and the emergence of arboviral diseases may form the basis for recommending effective control measures and contribute to an integrated approach to arboviral diseases management.

2. Invasive Alien Plants

Invasive plant species are defined by three main properties, (i) their bio-geographical origin (alien plants, introduced either accidentally or on purpose by living organisms), (ii) their ability to spread without human assistance (aggressive invasion of pristine environments or opportunistic establishment in disturbed habitats), and (iii) their negative effects, including economic, environmental, and aesthetic impacts [20]. Most species of IAPs belong to the three plant families Compositae, Poaceae, and Leguminosae [21]. The IAPs reviewed here are among those with potential relevance to arthropods and particularly to virus-transmitting mosquitoes. In particular, these are species that are able to rapidly fill “open” niches by fast growth and aggressive spread dynamics [22], and that occupy ecological niches similar to those preferred by disease vectors [23]. This concerns open water surfaces (IAPs colonizing aquatic and semi-aquatic habitats) or anthropogenically disturbed terrestrial areas where IAPs displace natural vegetation using allelochemicals [24] and by effectively competing for resources such as light, water, and nutrients [25]. In these cases, IAPs may substantially alter ecological conditions, differentially affecting arboviral mosquito vectors at different stages of their development. The main group of plants discussed in this review correspond to (i) floating aquatic plants and semi-aquatic helophytes, (ii) annual and perennial forbs, (iii) woody species, and (iv) succulent plants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Vascular plant species cited in this article as invasive for African countries and grouped according to their life forms.

Aquatic and semi-aquatic environments have been greatly affected by IAPs in Africa. Floating species such as water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes), water lettuce (Pistia stratiotes), and water fern (Salvinia molesta) are considered among the earliest introductions of alien plants into Africa [26,27,28]. Due to the azonality of aquatic environments, most of those species are ubiquitous. The neotropical species Mimosa pigra are predominant in semi-aquatic habitats such as swamps and floodplains. These aquatic IAPs were introduced into Africa as ornamental plants for artificial ponds and are causing huge ecological and economic problems [19].

Annual and perennial herbs mainly colonize ruderal (disturbed) places such as roadsides, quarries, and construction places [29], but may also occur as common weeds (segetal flora) in irrigated and rain-fed croplands [30]. Examples of IAPs in cultivated and fallow lands are the annuals Argemone mexicana, Bidens pilosa, Datura stramonium, Galinsoga parviflora, Tagetes minuta, and Parthenium hysterophorus. Because these weeds are short-lived and often outcompeted by perennial forbs and woods, their effects on the environment are usually neglected. However, of emerging ecological concern is P. hysterophorus due to its fast spread and dominant growth [29,31,32].

Woody species (trees and shrubs) are the most important group of IAPs based on their size and impact on vegetation structure. Many are broadly distributed across the continent in tropical and sub-tropical areas like the shrubs Chromolaena odorata [33,34] and Lantana camara [35,36]. The latter is often grown as a live fence around homes and occasionally croplands and is a preferred habitat of tsetse flies (Glossina spp.), the vectors carrying the parasitic protozoan that causes trypanosomiasis in humans and animals [37]. Others can invade protected areas like Broussonetia papyrifera [38], Psidium guajava [39], and Senna spectabilis [40]. Of greatest concern in this respect in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond is the rapid spread of Prosopis juliflora (mesquite), considered as one of the world’s worst invasive plant across the tropics [41,42].

Succulent plants are adapted to semi-arid conditions, occurring in stony shallow soils that are frequently used for rain-fed cultivation or as seasonal grazing places. Succulent IAPs, often neotropical Cactaceae like Austrocylindropuntia subulata, Opuntia ficus-indica, and O. stricta, frequently outcompete native succulents [19,43].

5. Potential Effects of Invasive Alien Plants on Viral Pathogen Transmission

Mosquito species of the Aedes, Culex, Mansonia, Eretmapodites, and Anopheles genera are tremendous threats to public health due to their ability to transmit viruses to humans and/or livestock [75]. Because viral susceptibility and transmission by a mosquito vector is affected by nutrition [76], the choice of nutrition is critical for the propagation of infectious pathogens to humans and livestock (Figure 1f). However, little to nothing is known about the role of plant nutrition of the mosquito vector on viral infection, replication, and transmission.

Besides the oviposition altering properties of plant debris in vector breeding sites, histopathological evidence showed that consumption of decaying plant leaves by larvae of Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus, and Cx. pipiens affected their midgut epithelial cells [77]. Disruption of the midgut epithelial cells may interfere with immature development, adult emergence, and possibly pathogen transmission abilities [78]. Though this does not directly point to all IAPs, it is known that the aquatic IAP Eichhornia crassipes is able to affect the midgut epithelia tissue of Cx. pipiens [79]. In addition, the fact that leaf litter of certain IAPs enhances the abundance of Culex spp. and Aedes spp. [11], makes it particularly interesting to investigate whether these plants also affect the adult vectors’ fitness and susceptibility to viral pathogens.

Both male and female mosquitoes rely on plant sugar for flight and survival [6,7], with possible additional reproductive and pathogen susceptibility benefits for female mosquitoes [9,13]. Recent studies have confirmed that certain secondary metabolites (toxins) from plants are ingested by mosquito vectors along with common plant sugars [80]. However, the fate and impact of the ingested plant secondary metabolites remains unclear, particularly for arboviral mosquito vectors. For malaria it is known that An. gambiae preferentially feeds on P. hysterophorus, though because of the plant’s relatively inferior sugar profile it appears that in terms of nutrition the plant does not have any adaptive significance to the vector [8,9,64,69]. Hence the vector’s feeding preference for P. hysterophorus could be a mere reflection of its wide availability caused by the rapid replacement of native vegetation by this highly aggressive IAP, its attractive odour [70], or due to other underlying physiological benefits that the plant offers the vector. It was therefore hypothesized that besides sugars, other constituents present in P. hysterophorus could benefit An. gambiae [64]. Parthenin, a sesquiterpene lactone present in P. hysterophorus, was isolated from recently plant-fed An. gambiae [80] and was later shown to block the transmission of the asexual stages of Plasmodium falciparum in infected mosquitoes [13], leading to speculations that the female mosquitoes preferentially seek sugar from P. hysterophorus to rid themselves of a plasmodium infection [80]. Though some of the anti-microbial properties of parthenin are well documented [13,81], its antiviral potential remains unknown and merits further investigation.

Thus, based on the recent promising results regarding malaria vectors [13,80], the potential suppressing or even enhancing properties of secondary plant metabolites on arbovirus vectors, especially those found in aggressively spreading IAPs in Africa, demands greater scientific attention. This should be accompanied by more detailed studies on plant feeding preferences in arboviral mosquito vectors, including the dengue vector Ae. aegypti but also vectors of other important arboviral diseases like RVFV.

6. Conclusions

The plant assemblage in an environment has the potential to influence the abundance and diversity of mosquito vectors and their ability to transmit infectious pathogens. In Africa, IAPs are dramatically altering ecologies and whole landscapes. We believe that this has profound consequences on the dynamics of arboviral mosquito vectors and on the epidemiology of important endemic arboviral diseases on the continent. Although not much is presently known, some initial studies on arboviral vectors and IAPs (immature development, plant sugar feeding preference, survival, reproductive fitness, and vector competence) are indicating a whole new area of research, which eventually might enrich our portfolio of integrated control options and risk analysis mapping of vector-borne viral diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B.A. and C.B.; methodology, S.B.A. and C.B.; validation, S.B.A., M.A., M.B., E.M.F., S.J., and C.B.; investigation, S.B.A., M.A., M.B., E.M.F., S.J., and C.B.; resources, C.B.; data curation, S.B.A., M.A., M.B., and C.B.; writing—S.B.A., M.A., M.B., and C.B.; writing—review and editing, S.B.A., M.A., M.B., E.M.F., S.J., and C.B.; visualization, S.B.A., M.A., M.B., E.M.F., S.J., and C.B.; supervision, C.B.; project administration, S.B.A. and C.B.; funding acquisition, S.J. and C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) through funding for the project “Future Infections” as part of the collaborative research center “Future Rural Africa”, funding code TRR 228/1.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- United Nations. Growing at a Slower Pace, World Population Is Expected to Reach 9.7 Billion in 2050 and Could Peak at Nearly 11 Billion Around 2100. UN DESA|United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/world-population-prospects-2019.html (accessed on 31 March 2020).

- Jones, B.A.; Grace, D.; Kock, R.; Alonso, S.; Rushton, J.; Said, M.Y.; McKeever, D.; Mutua, F.; Young, J.; McDermott, J.; et al. Zoonosis emergence linked to agricultural intensification and environmental change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8399–8404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junglen, S.; Kurth, A.; Kuehl, H.; Quan, P.-L.; Ellerbrok, H.; Pauli, G.; Nitsche, A.; Nunn, C.; Rich, S.M.; Lipkin, W.I.; et al. Examining landscape factors influencing relative distribution of mosquito genera and frequency of virus infection. EcoHealth 2009, 6, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer Steiger, D.B.; Ritchie, S.A.; Laurance, S.G.W. Mosquito communities and disease risk influenced by land use change and seasonality in the Australian tropics. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzoli, A.; Tagliapietra, V.; Cagnacci, F.; Marini, G.; Arnoldi, D.; Rosso, F.; Rosà, R. Parasites and wildlife in a changing world: The vector-host- pathogen interaction as a learning case. Int. J. Parasitol. Parasites Wildl. 2019, 9, 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, W.A. Mosquito Sugar feeding and reproductive energetics. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1995, 40, 443–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, C.M.; Witt, A.B.R.; Walsh, G.C.; Foster, W.A.; Murphy, S.T. Would the control of invasive alien plants reduce malaria transmission? A review. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, B.; Jackson, B.T.; Guseman, J.L.; Przybylowicz, C.M.; Stone, C.M.; Foster, W.A. Alteration of plant species assemblages can decrease the transmission potential of malaria mosquitoes. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 55, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda, H.; Gouagna, L.C.; Foster, W.A.; Jackson, R.R.; Beier, J.C.; Githure, J.I.; Hassanali, A. Effect of discriminative plant-sugar feeding on the survival and fecundity of Anopheles gambiae. Malar. J. 2007, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arum, S.O.; Weldon, C.W.; Orindi, B.; Tigoi, C.; Musili, F.; Landmann, T.; Tchouassi, D.P.; Affognon, H.D.; Sang, R. Plant resting site preferences and parity rates among the vectors of Rift Valley Fever in northeastern Kenya. Parasit. Vectors 2016, 9, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuthbert, R.N.; Dalu, T.; Mutshekwa, T.; Wasserman, R.J. Leaf inputs from invasive and native plants drive differential mosquito abundances. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 689, 652–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, A.M.; Allan, B.F.; Frisbie, L.A.; Muturi, E.J. Asymmetric effects of native and exotic invasive shrubs on ecology of the West Nile virus vector Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae). Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaich, J.N.; Mathias, D.K.; Torto, B.; Jackson, B.T.; Tao, D.; Ebrahimi, B.; Tarimo, B.B.; Cheseto, X.; Foster, W.A.; Dinglasan, R.R. The nonartemisinin sesquiterpene lactones parthenin and parthenolide block Plasmodium falciparum sexual stage Transmission. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2108–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardner, A.M.; Muturi, E.J.; Overmier, L.D.; Allan, B.F. Large-scale removal of invasive honeysuckle decreases mosquito and avian host abundance. EcoHealth 2017, 14, 750–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, G.C.; Junnila, A.; Traore, M.M.; Traore, S.F.; Doumbia, S.; Sissoko, F.; Dembele, S.M.; Schlein, Y.; Arheart, K.L.; Revay, E.E.; et al. The invasive shrub Prosopis juliflora enhances the malaria parasite transmission capacity of Anopheles mosquitoes: A habitat manipulation experiment. Malar. J. 2017, 16, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, C.M.; Jackson, B.T.; Foster, W.A. Effects of plant-community composition on the vectorial capacity and fitness of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 87, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choge, S.K.; Pasiecznik, N.M.; Harvey, M.; Wright, J.; Awan, S.Z.; Harris, P.J.C. Prosopis pods as human food, with special reference to Kenya. Water SA 2007, 33, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, A. Guide to the Naturalized and Invasive Plants of Laikipia; CABI: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, A.; Luke, Q. Guide to the Naturalized and Invasive Plants of Eastern Africa; CABI International: Wallingford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hierro, J.L.; Maron, J.L.; Callaway, R.M. A biogeographical approach to plant invasions: The importance of studying exotics in their introduced and native range. J. Ecol. 2005, 93, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyšek, P.; Pergl, J.; Essl, F.; Lenzner, B.; Dawson, W.; Kreft, H.; Weigelt, P.; Winter, M.; Kartesz, J.; Nishino, M.; et al. Naturalized alien flora of the world: Species diversity, taxonomic and phylogenetic patterns, geographic distribution and global hotspots of plant invasion. Preslia 2017, 89, 203–274. [Google Scholar]

- Vilà, M.; Espinar, J.L.; Hejda, M.; Hulme, P.E.; Jarošík, V.; Maron, J.L.; Pergl, J.; Schaffner, U.; Sun, Y.; Pyšek, P. Ecological impacts of invasive alien plants: A meta-analysis of their effects on species, communities and ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2011, 14, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleunen, M.V.; Weber, E.; Fischer, M. A meta-analysis of trait differences between invasive and non-invasive plant species. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belz, R.G.; Reinhardt, C.F.; Foxcroft, L.C.; Hurle, K. Residue allelopathy in Parthenium hysterophorus L.—Does parthenin play a leading role? Crop. Prot. 2007, 26, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Alvarez, M.; Heller, G.; Leparmarai, P.; Maina, D.; Malombe, I.; Bollig, M.; Vehrs, H. Land-use changes and the invasion dynamics of shrubs in Baringo. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2016, 10, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, D.M. The ecological relationships of aquatic plants at lake Naivasha, Kenya. Hydrobiologia 1992, 232, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, J.M.; Hill, M.P.; Villet, M.H. The effect of water hyacinth, Eichhornia crassipes (Martius) SolmsLaubach (Pontederiaceae), on benthic biodiversity in two impoundments on the New Year’s River, South Africa. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 2006, 31, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njambuya, J.; Triest, L. Comparative performance of invasive alien Eichhornia crassipes and native Ludwigia stolonifera under non-limiting nutrient conditions in Lake Naivasha, Kenya. Hydrobiologia 2010, 656, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wabuyele, E.; Lusweti, A.; Bisikwa, J.; Kyenune, G.; Clark, K.; Lotter, W.D.; McConnachie, A.J.; Wondi, M. A roadside survey of the invasive weed Parthenium hysterophorus (Asteraceae) in East Africa. J. East. Afr. Nat. His. 2015, 103, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittig, R.; Becker, U.; Ataholo, M. Weed communities of arable fields in the Sudanian and the Sahelian zone of West Africa. Phytocoenologia 2011, 41, 107–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamado, T.; Milberg, P. Weed flora in arable fields of eastern Ethiopia with emphasis on the occurrence of Parthenium hysterophorus. Weed Res. 2000, 40, 507–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, A.; Khaliq, A.; Ali, H.H.; Mahajan, G.; Chauhan, B.S. Interference and management of parthenium: The world’s most important invasive weed. Crop. Prot. 2015, 68, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Beest, M.; Howison, O.; Howison, R.A.; Dew, L.A.; Poswa, M.M.; Dumalisile, L.; Van, S.J. Successful control of the invasive shrub Chromolaena odorata in Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park. In Conserving Africa’s Mega-Diversity in the Anthropocene: The Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park Story; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 358–382. [Google Scholar]

- Zachariades, C.; Day, M.; Muniappan, R.; Reddy, G.V.P. Chromolaena odorata (L.) King and Robinson (Asteraceae). In Biological Control of Tropical Weeds Using Arthropods; Muniappan, R., Reddy, G.V.P., Raman, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 130–162. [Google Scholar]

- Habel, J.C.; Teucher, M.; Rödder, D.; Bleicher, M.-T.; Dieckow, C.; Wiese, A.; Fischer, C. Kenyan endemic bird species at home in novel ecosystem. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 2494–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teucher, M.; Fischer, C.; Busch, C.; Horn, M.; Igl, J.; Kerner, J.; Müller, A.; Mulwa, R.K.; Habel, J.C. A Kenyan endemic bird species Turdoides hindei at home in invasive thickets. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2015, 16, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, Z.; Guerin, P.M. Tsetse flies are attracted to the invasive plant Lantana camara. J. Insect Physiol. 2004, 50, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apetorgbor, M.M.; Bosu, P.P. Occurrence and control of paper mulberry (broussonetia papyrifera) in souther Ghana. Ghana J. For. 2011, 27, 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Adhiambo, R.; Muyekho, F.; Creed, I.F.; Enanga, E.; Shivoga, W.; Trick, C.G.; Obiri, J. Managing the invasion of guava trees to enhance carbon storage in tropical forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 432, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakibara, J.V.; Mnaya, B.J. Possible control of Senna spectabilis (Caesalpiniaceae), an invasive tree in Mahale mountains National park, Tanzania. Oryx 2002, 36, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmati, I.; Khorasani, N.; Shams-Esfandabad, B.; Riazi, B. Forthcoming risk of Prosopis juliflora global invasion triggered by climate change: Implications for environmental monitoring and risk assessment. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2019, 191, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, R.T.; Le Maitre, D.C.; van Wilgen, B.W.; Richardson, D.M. Towards a national strategy to optimise the management of a widespread invasive tree (Prosopis species; mesquite) in South Africa. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 27, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, R.T.; Witt, A.B.R.; Piroris, F.M.; van Wilgen, B.W. Distribution and socio-ecological impacts of the invasive alien cactus Opuntia stricta in eastern Africa. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 2427–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, S.B.; Tchouassi, D.P.; Bastos, A.D.S.; Sang, R. Assessment of risk of dengue and yellow fever virus transmission in three major Kenyan cities based on Stegomyia indices. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronenwetter-Koepel, T.A.; Meece, J.K.; Miller, C.A.; Reed, K.D. Surveillance of above- and below-ground mosquito breeding habitats in a rural midwestern community: Baseline data for larvicidal control measures against West Nile virus vectors. Clin. Med. Res. 2005, 3, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaid, S.; Samraoui, B.; Thomas, J.; El-Serehy, H.A.; Alfarhan, A.H.; Schneider, W.; O’connell, M. An overview of wetlands of Saudi Arabia: Values, threats, and perspectives. Ambio 2017, 46, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, C.E.; Ironside, A.; Mansfield, S. A comparison of oviposition preference in the presence of three aquatic plants by the mosquitoes “Culex annulirostris” Skuse and “Culex quinquefasciatus” Say (Culicidae: Diptera) in laboratory tests. Gen. Appl. Entomol. J. Entomol. Soc. New South. Wales. 2013, 41, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Tantely, L.M.; Boyer, S.; Fontenille, D. A review of mosquitoes associated with Rift Valley fever virus in Madagascar. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2015, 92, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turell, M.J.; Kay, B.H. Susceptibility of selected strains of Australian mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) to Rift Valley fever virus. J. Med. Entomol. 1998, 35, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van den Hurk, A.F.; Hall-Mendelin, S.; Webb, C.E.; Tan, C.S.E.; Frentiu, F.D.; Prow, N.A.; Hall, R.A. Role of enhanced vector transmission of a new West Nile virus strain in an outbreak of equine disease in Australia in 2011. Parasit. Vectors 2014, 7, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, G.; Ghosh, A.; Biswas, D.; Chatterjee, S.N. Host plant preference of Mansonia Mosquitoes. J. Aquat. Plant. Manag. 2006, 44, 142–144. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, A.M.; Anderson, T.K.; Hamer, G.L.; Johnson, D.E.; Varela, K.E.; Walker, E.D.; Ruiz, M.O. Terrestrial vegetation and aquatic chemistry influence larval mosquito abundance in catch basins, Chicago, USA. Parasit. Vectors 2013, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, R.W.; Dadd, R.H.; Walker, E.D. Feeding behavior, natural food, and nutritional relationships of larval mosquitoes. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1992, 37, 349–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Tezanos Pinto, P.; Allende, L.; O’Farrell, I. Influence of free-floating plants on the structure of a natural phytoplankton assemblage: An experimental approach. J. Plankton Res. 2007, 29, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipyab, P.C.; Khaemba, B.M.; Mwangangi, J.M.; Mbogo, C.M. The physicochemical and environmental factors affecting the distribution of Anopheles merus along the Kenyan coast. Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuno, N.; Kohzu, A.; Tayasu, I.; Nakayama, T.; Githeko, A.; Yan, G. An algal diet accelerates larval growth of Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae) and Anopheles arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2018, 55, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farajollahi, A.; Fonseca, D.M.; Kramer, L.D.; Kilpatrick, A.M. “Bird biting” mosquitoes and human disease: A review of the role of Culex pipiens complex mosquitoes in epidemiology. Infect. Genet. Evol. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evol. Genet. Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwabiah, A.B.; Stoskopf, N.C.; Voroney, R.P.; Palm, C.A. Nitrogen and Phosphorus release from decomposing leaves under sub-humid Tropical conditions. Biotropica 2001, 33, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.; Heller, G.; Malombe, I.; Matheka, K.W.; Choge, S.; Becker, M. Classification of Prosopis juliflora invasion in the Lake Baringo basin and environmental correlations. Afr. J. Ecol. 2019, 57, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.; Diuk-Wasser, M.; Andreadis, T.; Fish, D. Remotely-sensed vegetation indices identify mosquito clusters of West Nile virus vectors in an urban landscape in the Northeastern United States. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008, 8, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyua, P.M.; Murithi, R.M.; Ithondeka, P.; Hightower, A.; Thumbi, S.M.; Anyangu, S.A.; Kiplimo, J.; Bett, B.; Vrieling, A.; Breiman, R.F.; et al. Predictive factors and risk mapping for Rift Valley fever epidemics in Kenya. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0144570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosomtai, G.; Evander, M.; Sandström, P.; Ahlm, C.; Sang, R.; Hassan, O.A.; Affognon, H.; Landmann, T. Association of ecological factors with Rift Valley fever occurrence and mapping of risk zones in Kenya. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 46, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyamba, A.; Chretien, J.-P.; Small, J.; Tucker, C.J.; Formenty, P.B.; Richardson, J.H.; Britch, S.C.; Schnabel, D.C.; Erickson, R.L.; Linthicum, K.J. Prediction of a Rift Valley fever outbreak. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda, H.; Gouagna, L.C.; Nyandat, E.; Kabiru, E.W.; Jackson, R.R.; Foster, W.A.; Githure, J.I.; Beier, J.C.; Hassanali, A. Discriminative feeding behaviour of Anopheles gambiae s.s. on endemic plants in western Kenya. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2007, 21, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, E.; Swallow, B. Prosopis juliflora invasion and rural livelihoods in the Lake Baringo area of Kenya. Conserv. Soc. 2008, 6, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Pasiecznik, N.M.; Vall, A.O.M.; Nourissier-Mountou, S.; Danthu, P.; Murch, J.; McHugh, M.J.; Harris, P.J.C. Discovery of a life history shift: Precocious flowering in an introduced population of Prosopis. Biol. Invasions 2006, 8, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.J.C.; Pasiecznik, N.M.; Smith, S.J.; Billington, J.M.; Ramírez, L. Differentiation of Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC and P. pallida (H. & B. ex. Willd.) HBK using foliar characters and ploidy. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 180, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Sissoko, F.; Junnila, A.; Traore, M.M.; Traore, S.F.; Doumbia, S.; Dembele, S.M.; Schlein, Y.; Traore, A.S.; Gergely, P.; Xue, R.-D.; et al. Frequent sugar feeding behavior by Aedes aegypti in Bamako, Mali makes them ideal candidates for control with attractive toxic sugar baits (ATSB). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikbakhtzadeh, M.R.; Terbot, J.W.; Foster, W.A. Survival value and sugar access of four East African plant species attractive to a laboratory strain of sympatric Anopheles gambiae (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Med. Entomol. 2016, 53, 1105–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyasembe, V.O.; Teal, P.E.; Mukabana, W.R.; Tumlinson, J.H.; Torto, B. Behavioural response of the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae to host plant volatiles and synthetic blends. Parasit. Vectors 2012, 5, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyasembe, V.O.; Cheseto, X.; Kaplan, F.; Foster, W.A.; Teal, P.E.A.; Tumlinson, J.H.; Borgemeister, C.; Torto, B. The invasive American weed Parthenium hysterophorus can negatively impact malaria control in Africa. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gary, R.E.; Foster, W.A. Anopheles gambiae feeding and survival on honeydew and extra-floral nectar of peridomestic plants. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2004, 18, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leak, S.G.A. Their Role in the Epidemiology and Control of Trypanosomosis; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Nyasembe, V.O.; Tchouassi, D.P.; Pirk, C.W.W.; Sole, C.L.; Torto, B. Host plant forensics and olfactory-based detection in Afro-tropical mosquito disease vectors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braack, L.; Gouveia de Almeida, A.P.; Cornel, A.J.; Swanepoel, R.; de Jager, C. Mosquito-borne arboviruses of African origin: Review of key viruses and vectors. Parasit. Vectors 2018, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weger-Lucarelli, J.; Auerswald, H.; Vignuzzi, M.; Dussart, P.; Karlsson, E.A. Taking a bite out of nutrition and arbovirus infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018, 12, e0006247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.P.; Rey, D.; Pautou, M.P.; Meyran, J.C. Differential toxicity of leaf litter to dipteran larvae of mosquito developmental sites. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2000, 75, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.-S.; Webster, J.A.; Madzokere, E.T.; Stephenson, E.B.; Herrero, L.J. Mosquito antiviral defense mechanisms: A delicate balance between innate immunity and persistent viral infection. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assar, A.A.; el-Sobky, M.M. Biological and histopathological studies of some plant extracts on larvae of Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae). J. Egypt Soc. Parasitol. 2003, 33, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nyasembe, V.O.; Teal, P.E.A.; Sawa, P.; Tumlinson, J.H.; Borgemeister, C.; Torto, B. Plasmodium falciparum infection increases Anopheles gambiae attraction to nectar sources and sugar uptake. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, K.; Vanisree, R.; Devi, Y.P. Study on antibacterial activity of Parthenium hysterophorus L. leaf and flower extracts. J. Sci. Res. Pharm. 2015, 4, 121–124. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).