Potential Maternal and Infant Outcomes from Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (SARS-CoV-2) Infecting Pregnant Women: Lessons from SARS, MERS, and Other Human Coronavirus Infections

Abstract

1. Introduction

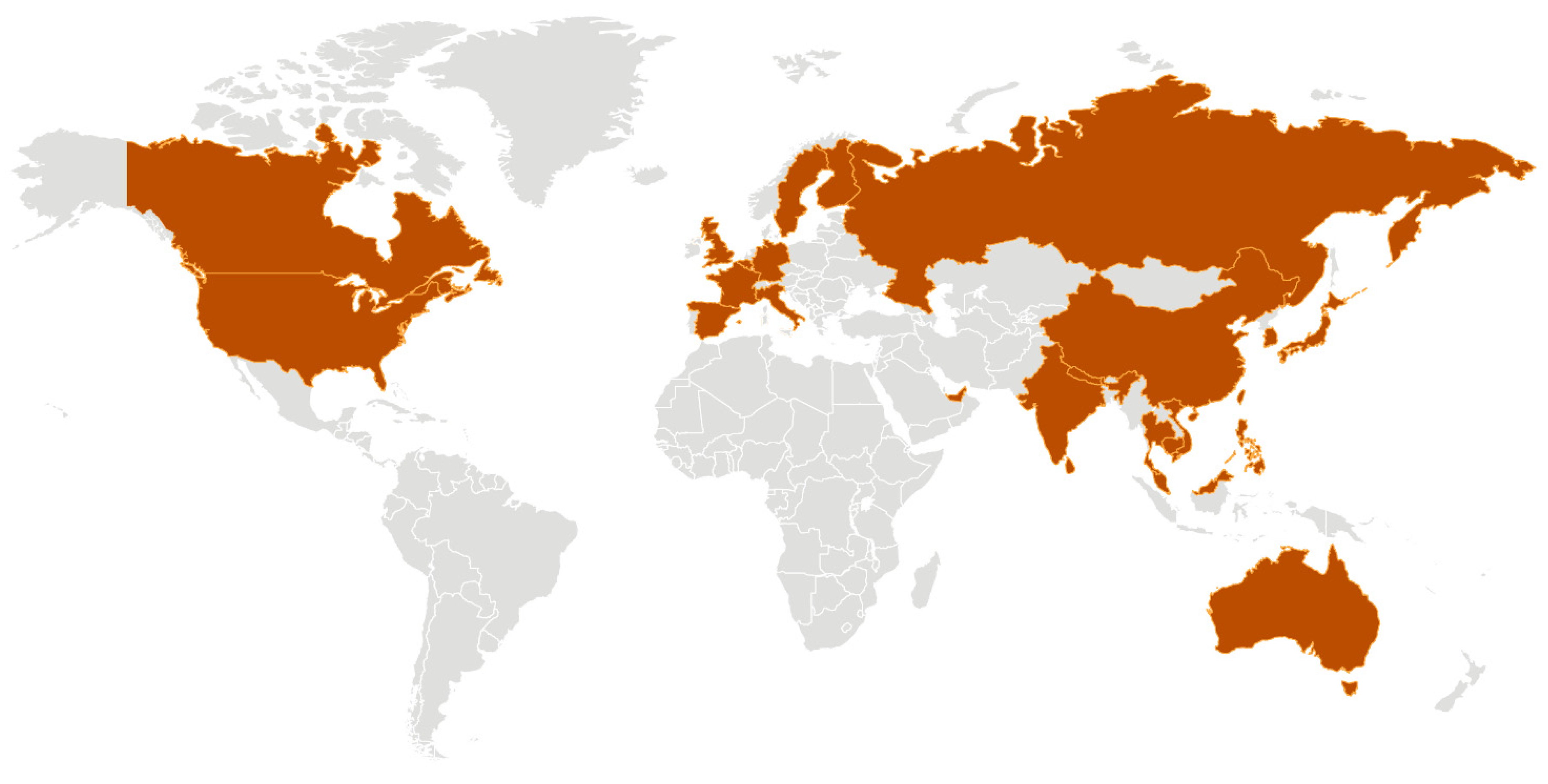

2. The 2019 Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (SARS-CoV-2) Outbreak in Wuhan

3. Pneumonia Occurring during Pregnancy

4. The 2002–2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Epidemic

5. SARS and Pregnancy

6. Placental Pathology of SARS

7. Safe Management of Pregnant Women with SARS

- “All hospitals should have infection control systems in place to ensure that alerts regarding changes in exposure risk factors for SARS or other potentially serious communicable diseases are conveyed promptly to clinical units, including the labour and delivery unit.

- At times of SARS outbreaks, all pregnant patients being assessed or admitted to the hospital should be screened for symptoms of and risk factors for SARS.

- Upon arrival in the labour triage unit, pregnant patients with suspected and probable SARS should be placed in a negative pressure isolation room with at least 6 air exchanges per hour. All labour and delivery units caring for suspected and probable SARS should have available at least one room in which patients can safely labour and deliver while in need of airborne isolation.

- If possible, labour and delivery (including operative delivery or Caesarean section) should be managed in a designated negative pressure isolation room, by designated personnel with specialized infection control preparation and protective gear.

- Either regional or general anaesthesia may be appropriate for delivery of patients with SARS.

- Neonates of mothers with SARS should be isolated in a designated unit until the infant has been well for 10 days, or until the mother’s period of isolation is complete. The mother should not breastfeed during this period.

- A multidisciplinary team, consisting of obstetricians, nurses, pediatricians, infection control specialists, respiratory therapists, and anaesthesiologists, should be identified in each unit and be responsible for the unit organization and implementation of SARS management protocols.

- Staff caring for pregnant SARS patients should not care for other pregnant patients. Staff caring for pregnant SARS patients should be actively monitored for fever and other symptoms of SARS. Such individuals should not work in the presence of any SARS symptoms within 10 days of exposure to a SARS patient.

- All health care personnel, trainees, and support staff should be trained in infection control management and containment to prevent spread of the SARS virus.

- Regional health authorities in conjunction with hospital staff should consider designating specific facilities or health care units, including primary, secondary, or tertiary health care centers, to care for patients with SARS or similar illnesses.”

8. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS)

9. MERS and Pregnancy

10. MERS Prevention and Treatment

11. Other Coronaviruses and Pregnancy

12. Participation of Pregnant Women in the Development of a Coronavirus Vaccine

“Given the rapid global spread of the nCoV-2019 virus the world needs to act quickly and in unity to tackle this disease. Our intention with this work is to leverage our work on the MERS coronavirus and rapid response platforms to speed up vaccine development.”

13. Current Status of 2019-nCoV (SARS-CoV-2) Infection of Pregnant Women and Neonates

“This reminds us to pay attention to mother-to-child being a possible route of coronavirus transmission”

“Whether it was the baby’s nanny who passed the virus to the mother who passed it to the baby, we cannot be sure at the moment. But we can confirm that the baby was in close contact with patients infected with the new coronavirus, which says newborns can also be infected”

“It’s more likely that the baby contracted the virus from the hospital environment, the same way healthcare workers get infected by the patients they treat,”

“It’s quite possible that the baby picked it up very conventionally—by inhaling virus droplets that came from the mother coughing.”

“As far as I am aware there is currently no evidence that the novel coronavirus can be transmitted in the womb. When a baby is born vaginally it is exposed to the mother’s gut microbiome, therefore if a baby does get infected with coronavirus a few days after birth we currently cannot tell if the baby was infected in the womb or during birth.”

14. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hui, D.S. Epidemic and emerging coronaviruses (severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome). Clin. Chest Med. 2017, 38, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Z.; Xu, Y.; Bao, L.; Zhang, L.; Yu, P.; Qu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhao, W.; Han, Y.; Qin, C. From SARS to MERS, thrusting coronaviruses into the spotlight. Viruses 2019, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, J.; Li, F.; Shi, Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICTV 9th Report (2011). Coronaviridae. Available online: https://talk.ictvonline.org/ictv-reports/ictv_9th_report/positive-sense-rna-viruses-2011/w/posrna_viruses/222/coronaviridae (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Perlman, S. Another decade, another coronavirus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hui, D.S.C.; Zumla, A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: Historical, epidemiologic, and clinical features. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 33, 869–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Guan, X.; Wu, P.; Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Tong, Y.; Ren, R.; Leung, K.S.M.; Lau, E.H.Y.; Wong, J.Y.; et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Wuhan Seafood Market May Not Be Source of Novel Virus Spreading Globally. Available online: https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/01/wuhan-seafood-market-may-not-be-source-novel-virus-spreading-globally (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-nCoV) (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- WHO. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Situation Report–20. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200209-sitrep-20-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=6f80d1b9_2 (accessed on 9 February 2020).

- Wee, S.-L.; McNeil, D.G., Jr.; Hernández, J.C. W.H.O. Declares Global Emergency as Wuhan Coronavirus Spreads. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/30/health/coronavirus-world-health-organization.html (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Benedetti, T.J.; Valle, R.; Ledger, W.J. Antepartum pneumonia in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 1982, 144, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, K.; LaSala, A. Risk factors associated with the increasing prevalence of pneumonia during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 163, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madinger, N.E.; Greenspoon, J.S.; Eilrodt, A.G. Pneumonia during pregnancy: Has modern technology improved maternal and fetal outcome? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1989, 161, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visscher, H.C.; Visscher, R.D. Indirect obstetric deaths in the state of Michigan 1960–1968. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1971, 109, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, F.B.; Pastorek, J.G. Pneumonia during pregnancy. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996, 39, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, D.J.; Theiler, R.N.; Rasmussen, S.A. Emerging infections and pregnancy. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2006, 12, 1638–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargent, I.L.; Redman, C. Immunobiologic adaptations of pregnancy. In Medicine of the Fetus and Mother; Reece, E.A., Hobbins., J.C., Mahoney, M.J., Petrie, R.H., Eds.; JB Lippincott Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; pp. 317–327. [Google Scholar]

- Nyhan, D.; Bredin, C.; Quigley, C. Acute respiratory failure in pregnancy due to staphylococcal pneumonia. Ir. Med. J. 1983, 76, 320–321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weinberger, S.; Weiss, S.; Cohen, W.; Weiss, J.; Johnson, T.S. Pregnancy and the lung. Am. Rev. Resp. Dis. 1980, 121, 559–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.W. Influenza occurring in pregnant women; a statistical study of thirteen hundred and fifty cases. JAMA 1919, 72, 978–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickhoff, T.C.; Sherman, I.L.; Serfling, R.E. Observations on excess mortality associated with epidemic influenza. JAMA 1961, 176, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada. Learning from SARS: Renewal of Public Health in Canada—SARS in Canada: Anatomy of an Outbreak. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/learning-sars-renewal-public-health-canada/chapter-2-sars-canada-anatomy-outbreak.html (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- Peterson, M.J. Reporting Incidence of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Appendix A: Chronology. Available online: https://www.umass.edu/sts/pdfs/SARS_AChrono.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- WHO. Consensus Document on the Epidemiology of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Available online: https://www.who.int/csr/sars/en/WHOconsensus.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2020).

- Wong, S.F.; Chow, K.M.; de Swiet, M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome and pregnancy. BJOG 2003, 110, 641–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.F.; Chow, K.M.; Leung, T.N.; Ng, W.F.; Ng, T.K.; Shek, C.C.; Ng, P.C.; Lam, P.W.; Ho, L.C.; To, W.W.; et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 191, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.C.; So, K.W.; Leung, T.F.; Cheng, F.W.; Lyon, D.J.; Wong, W.; Cheung, K.L.; Fung, K.S.; Lee, C.H.; Li, A.M.; et al. Infection control for SARS in a tertiary neonatal centre. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003, 88, F405–F409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, P.C.; Leung, C.W.; Chiu, W.K.; Wong, S.F.; Hon, E.K. SARS in newborns and children. Biol. Neonate. 2004, 85, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, C.; McGeer, A.; Tai, K.F.Y.; Sermer, M. No. 225-Management guidelines for obstetric patients and neonates born to mothers with suspected or probable severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2017, 39, e130–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, C.M.; Wong, S.F.; Leung, T.N.; Chow, K.M.; Yu, W.C.; Wong, T.Y.; Lai, S.T.; Ho, L.C. A case-controlled study comparing clinical course and outcomes of pregnant and non-pregnant women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. BJOG 2004, 111, 771–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.P.; Wang, Y.H.; Chen, L.N.; Zhang, R.; Xie, Y.F. Clinical analysis of pregnancy in second and third trimesters complicated severe acute respiratory syndrome. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2003, 38, 516–520. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, C.A.; Lowther, S.A.; Birch, T.; Tan, C.; Sorhage, F.; Stockman, L.; McDonald, C.; Lingappa, J.R.; Bresnitz, E. SARS and pregnancy: A case report. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, E.; Duncan, D.; Reiken, M.; Perry, R.; Messick, J.; Sheedy, C.; Haase, J.; Gorab, J. SARS in pregnancy. AWHONN Lifelines 2004, 8, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockman, L.J.; Lowther, S.A.; Coy, K.; Saw, J.; Parashar, U.D. SARS during pregnancy, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004, 10, 1689–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudin, M.H.; Steele, D.M.; Sgro, M.D.; Read, S.E.; Kopplin, P.; Gough, K.A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome in pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 105, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, C.C.; Ng, P.C.; Fung, G.P.; Cheng, F.W.; Chan, P.K.; Peiris, M.J.; Lee, K.H.; Wong, S.F.; Cheung, H.M.; Li, A.M.; et al. Infants born to mothers with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Pediatrics 2003, 112, e254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.M.; Ng, P.C. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in neonates and children. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005, 90, F461–F465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Ng, W.F.; Wong, S.F.; Lam, A.; Mak, Y.F.; Yao, H.; Lee, K.C.; Chow, K.M.; Yu, W.C.; Ho, L.C. The placentas of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: A pathophysiological evaluation. Pathology 2006, 38, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poutanen, S.M.; Low, D.E.; Henry, B.; Finkelstein, S.; Rose, D.; Green, K.; Tellier, R.; Draker, R.; Adachi, D.; Ayers, M.; et al. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 1995–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seto, W.H.; Tsang, D.; Yung, R.W.; Ching, T.Y.; Ng, T.K.; Ho, M.; Ho, L.M.; Peiris, J.S.M.; Advisors of Expert SARS group of Hospital Authority. Effectiveness of precautions against droplets and contact in prevention of nosocomial transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2003, 361, 1519–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, L.S. The SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: What lessons have we learned? J. R. Soc. Med. 2003, 96, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maxwell, C.; McGeer, A.; Tai, K.F.Y.; Sermer, M.; Maternal Fetal Medicine Committee; Infectious Disease Committee. Management guidelines for obstetric patients and neonates born to mothers with suspected or probable severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2009, 31, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Background. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Assiri, A.; Abedi, G.R.; Almasry, M.; Bin Saeed, A.; Gerber, S.I.; Watson, J.T. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection during pregnancy: A report of 5 cases from Saudi Arabia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 951–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Fact Sheet. 2015. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/downloads/factsheet-mers_en.pdf (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Jeong, S.Y.; Sung, S.I.; Sung, J.H.; Ahn, W.Y.; Kang, E.S.; Chang, Y.S.; Park, S.P.; Kim, J.H. MERS-CoV infection in pregnant woman in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2017, 32, 1717–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) Overview. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/index.html (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Memish, Z.A.; Sumla, A.L.; Al-Hakeem, R.F.; Al-Rabeeah, A.A.; Stephens, G.M. Family cluster of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 2487–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijawi, B.; Abdallat, M.; Sayaydeh, A.; Alqasrawi, S.; Haddadin, A.; Jaarour, N.; Alsheikh, S.; Alsanouri, T. Novel coronavirus infections in Jordan, April 2012: Epidemiological findings from a retrospective investigation. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2013, 19, S12–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboho, I.K.; Tomczyk, S.M.; Al-Asmari, A.M.; Banjar, A.A.; Al-Mugti, H.; Aloraini, M.S.; Alkhaldi, K.Z.; Almohammadi, E.L.; Alraddadi, B.M.; Gerber, S.I.; et al. 2014 MERS-CoV outbreak in Jeddah—A link to health care facilities. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, J.C.; Nguyen, D.; Aden, B.; Al Bandar, Z.; Al Dhaheri, W.; Abu Elkheir, K.; Khudair, A.; Al Mulla, M.; El Saleh, F.; Imambaccus, H.; et al. Transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in healthcare settings, Abu Dhabi. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, M.D.; Park, W.B.; Park, S.W.; Choe, P.G.; Bang, J.H.; Song, K.H.; Kim, E.S.; Kim, H.B.; Kim, N.J. Middle East respiratory syndrome: What we learned from the 2015 outbreak in the Republic of Korea. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd, H.A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) origin and animal reservoir. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemida, H.G.; Elmoslemany, A.; Al-Hizab, F.; Alnaeem, A.; Almathen, F.; Faye, B.; Chu, D.K.W.; Perera, R.A.; Peiris, M. Dromedary camels and the transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alserehi, H.; Wali, G.; Alshukairi, A.; Alraddadi, B. Impact of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) on pregnancy and perinatal outcome. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, S.; Rawal, G.; Baxi, M. An Overview of the latest infectious diseases around the world. J. Comm. Health Manag. 2016, 3, 41–43. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A.; El Masry, K.M.; Ravi, M.; Sayed, F. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus during pregnancy, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates 2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 515–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaraj, S.H.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection during pregnancy: Report of two cases & review of literature. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2019, 52, 501–503. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, D.C.; Iblan, I.; Alqasrawi, S.; Al Nsour, M.; Rha, B.; Tohme, R.A.; Abedi, G.R.; Farag, N.H.; Haddadin, A.; Al Sanhouri, T.; et al. Stillbirth during infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, 1870–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Update on therapeutic options for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2017, 15, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagneur, A.; Dirson, E.; Audebert, S.; Vallet, S.; Quillien, M.C.; Baron, R.; Laurent, Y.; Collet, M.; Sizun, J.; Oger, E.; et al. Vertical transmission of human coronavirus. Prospective pilot study. Pathol. Biol. 2007, 55, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagneur, A.; Dirson, E.; Audebert, S.; Vallet, S.; Legrand-Quillien, M.C.; Laurent, Y.; Collet, M.; Sizun, J.; Oger, E.; Payan, C. Materno-fetal transmission of human coronaviruses: A prospective pilot study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008, 27, 863–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillim-Ross, L.; Subbarao, K. Emerging respiratory viruses: Challenges and vaccine strategies. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 614–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.-P.; Wang, N.-C.; Chang, Y.-H.; Tian, X.-Y.; Na, D.-Y.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Zheng, L.; Lan, T.; Wang, L.-F.; Liang, G.-D. Duration of antibody responses after severe acute respiratory syndrome. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 1562–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.T.; Sbrana, E.; Iwata-Yoshikawa, N.; Newman, P.C.; Garron, T.; Atmar, R.L.; Peters, C.J.; Couch, R.B. Immunization with SARS coronavirus vaccines leads to pulmonary immunopathology on challenge with the SARS virus. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.A. Clinical trials and administration of Zika virus vaccine in pregnant women: Lessons (that should have been) learned from excluding immunization with the Ebola vaccine during pregnancy and lactation. Vaccines (Basel) 2018, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.A. Being pregnant during the Kivu Ebola virus outbreak in DR Congo: The rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine and its accessibility by mothers and infants during humanitarian crises and in conflict areas. Vaccines 2020, 8, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.A. Maternal and infant death and the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine through three recent Ebola virus epidemics-West Africa, DRC Équateur and DRC Kivu: 4 years of excluding pregnant and lactating women and their infants from immunization. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2019, 6, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations. CEPI to Fund Three Programmes to Develop Vaccines against the Novel Coronavirus, nCoV-2019. 23 January 2020. Available online: https://cepi.net/news_cepi/cepi-to-fund-three-programmes-to-develop-vaccines-against-the-novel-coronavirus-ncov-2019/ (accessed on 29 January 2020).

- Pong, W. A Dozen Vaccine Programs Underway as WHO Declares Coronavirus Public Health Emergency. Biocentury. 30 January 2020. Available online: https://www.biocentury.com/article/304328/industry-and-academic-centers-are-rushing-to-create-new-vaccines-and-therapeutics-targeting-coronavirus (accessed on 2 February 2020).

- WHO. WHO Target Product Profiles for MERS-CoV Vaccines. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/blueprint/what/research-development/MERS_CoV_TPP_15052017.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Graham, A.L. When is it acceptable to vaccinate pregnant women? Risk, ethics, and politics of governance in epidemic crises. Curr. Trop. Med. Rep. 2019, 6, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinbuch, Y. Chinese Baby Tests Positive for Coronavirus 30 Hours after Birth. Available online: https://nypost.com/2020/02/05/chinese-baby-tests-positive-for-coronavirus-30-hours-after-birth/ (accessed on 9 February 2020).

- Woodward, A. A Pregnant Mother Infected with the Coronavirus Gave Birth, and Her Baby Tested Positive 30 Hours Later. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/wuhan-coronavirus-in-infant-born-from-infected-mother-2020-2 (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Gillespie, T. Coronavirus: Doctors Fear Pregnant Women Can Pass on Illness after Newborn Baby Is Diagnosed. Available online: https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-doctors-fear-pregnant-women-can-pass-on-illness-after-newborn-baby-is-diagnosed-11926968 (accessed on 8 February 2020).

- Science Media Centre. Expert Reaction to Newborn Baby Testing Positive for Coronavirus in Wuhan. Available online: https://www.sciencemediacentre.org/expert-reaction-to-newborn-baby-testing-positive-for-coronavirus-in-wuhan/ (accessed on 9 February 2020).

- Alvarado, M.G.; Schwartz, D.A. Zika virus infection in pregnancy, microcephaly and maternal and fetal health—What we think, what we know, and what we think we know. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2017, 141, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schwartz, D.A.; Graham, A.L. Potential Maternal and Infant Outcomes from Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (SARS-CoV-2) Infecting Pregnant Women: Lessons from SARS, MERS, and Other Human Coronavirus Infections. Viruses 2020, 12, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12020194

Schwartz DA, Graham AL. Potential Maternal and Infant Outcomes from Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (SARS-CoV-2) Infecting Pregnant Women: Lessons from SARS, MERS, and Other Human Coronavirus Infections. Viruses. 2020; 12(2):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12020194

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchwartz, David A., and Ashley L. Graham. 2020. "Potential Maternal and Infant Outcomes from Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (SARS-CoV-2) Infecting Pregnant Women: Lessons from SARS, MERS, and Other Human Coronavirus Infections" Viruses 12, no. 2: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12020194

APA StyleSchwartz, D. A., & Graham, A. L. (2020). Potential Maternal and Infant Outcomes from Coronavirus 2019-nCoV (SARS-CoV-2) Infecting Pregnant Women: Lessons from SARS, MERS, and Other Human Coronavirus Infections. Viruses, 12(2), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12020194