Abstract

Emerging infectious diseases are of great concern to public health, as highlighted by the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Such diseases are of particular danger during mass gathering and mass influx events, as large crowds of people in close proximity to each other creates optimal opportunities for disease transmission. The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia are two countries that have witnessed mass gatherings due to the arrival of Syrian refugees and the annual Hajj season. The mass migration of people not only brings exotic diseases to these regions but also brings new diseases back to their own countries, e.g., the outbreak of MERS in South Korea. Many emerging pathogens originate in bats, and more than 30 bat species have been identified in these two countries. Some of those bat species are known to carry viruses that cause deadly diseases in other parts of the world, such as the rabies virus and coronaviruses. However, little is known about bats and the pathogens they carry in Jordan and Saudi Arabia. Here, the importance of enhanced surveillance of bat-borne infections in Jordan and Saudi Arabia is emphasized, promoting the awareness of bat-borne diseases among the general public and building up infrastructure and capability to fill the gaps in public health preparedness to prevent future pandemics.

1. Introduction

Experts have been warning about the possibility of a pandemic threat, and the lack of preparedness at national levels, for many years [1]. Despite such warnings and in spite of the existence of the World Health Organization (WHO) International Health Regulations (IHR), coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) still caught the majority of the world off-guard, and some governments struggled to contain the viral outbreak as it spread through populations worldwide. Healthcare systems in many countries have been overwhelmed as the spread of COVID-19 resulted in a shortage of healthcare workers and resources [2]. The COVID-19 pandemic is a stark reminder of the ongoing global public health challenges created by emerging infectious diseases and global movements of people and animals, prompting the need for “robust research to understand the basic biology of new organisms and our susceptibilities to them” [3].

Emerging infectious diseases, which are diseases that have appeared or affected a population for the first time or have existed previously but are rapidly increasing either by the number of cases or by geographical spread, pose a major threat to human health and are often of zoonotic origin [4]. The emergence of infectious disease is partly driven by environmental changes that affect interactions between humans and animals in such a way so as to initiate a cross-species transmission (CST) event, or a host switching event [5]. CST occurs when a virus spreads to a new host species in a sustained manner after initial infection, i.e., successfully completes the viral infectious cycle in the new host species [6]. This may or may not lead to onward transmission in the new host species. If adaptation of the virus occurs resulting in sustained onward transmission, it is a host switching event. In many cases, infectious disease emergence in humans arises via an amplifier and intermediate hosts, exposing humans to pathogens from animals that would normally have little human contact [7]. Some examples of emerging infectious diseases that spread to humans through intermediate hosts include human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E), which is transmitted to humans through camelids, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), which is transmitted to humans through palm civets [8].

Bats have been identified as natural reservoirs for many families of viruses that cause clinically relevant diseases in humans, including bunyaviruses (febrile diseases), coronaviruses (mild and severe respiratory tract infections), hepaciviruses (hepatitis), herpesviruses (skin lesions and malignancies), lyssaviruses (rabies), orthoreoviruses (mild gastroenteritis and upper respiratory infection), paramyxoviruses (measles and mumps), and pegiviruses (encephalitis), among others [9,10,11]. New analyses reveal that the number of zoonotic viruses in avian and mammalian orders increases in proportion to the number of species, and, as a diverse mammalian order themselves, bats could potentially carry many zoonotic viruses [12].

Due to frequent CST events, bat-borne viral infections are a major cause of emerging infectious diseases in humans via a number of transmission mechanisms, which include bat bites and scratches, exposure to bat urine, and ingestion of bats [13]. Particularly, viral shedding, which is the release of viruses from host cells, in bats has been reported to coincide with the peak periods of CST to human and other animal populations [14,15,16,17]. Some of the most prominent host-switching events to humans have involved coronaviruses, resulting in the zoonotic introduction of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV, and, most recently, SARS-CoV-2, which is responsible for the ongoing pandemic.

The Eastern Mediterranean and Southeast Asian regions are highly vulnerable to emerging infectious and parasitic diseases, which are responsible for around 15% of morbidities and mortalities in the Eastern Mediterranean [18]. In fact, pneumonia and acute respiratory infections were reported to be a leading cause of death in the Eastern Mediterranean region, and they were often associated with zoonotic pathogens such as avian influenza A, the pandemic H1N1/09 virus, and MERS-CoV [19]. Alarmingly, the public healthcare systems in almost every Eastern Mediterranean country were inadequately prepared to respond effectively to a viral epidemic [20]. This inadequacy has only been exacerbated by the ongoing wars, civil unrest, population growth, and an aging population, which have all contributed to the spread of communicable diseases in a region which is already regularly exposed to mass influx events and mass gatherings [21].

The Arab world, which is a part of the Eastern Mediterranean region, is no stranger to the challenges posed by mass influx events and mass gatherings, as can be clearly seen in the cases of Jordan, with its role in the Syrian refugee crisis, and Saudi Arabia, as the main destination of religious pilgrimage. In fact, the annual mass religious gatherings that occur in Eastern Mediterranean countries such as Iran, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia have been cited as an additional challenge that complicates SARS-CoV-2 containment efforts in the region [22]. Additionally, refugee populations have been identified as having a heightened level of vulnerability to SARS-CoV-2, as their living conditions can make it difficult to practice the necessary public health measures, including physical distancing, self-isolation, and quarantine [23]. As a result, the present review was carried out to explore the public health preparedness in Jordan and Saudi Arabia for future pandemics, the possibility of which is exacerbated by the presence of native bat species whose habitats are increasingly being encroached upon by human populations.

2. Mass Influxes and Gatherings

Infectious diseases pose a significant risk to mass gathering and influx events, as they can easily spread between individuals and overwhelm the host country’s healthcare system [24]. Mass influxes occur when a large number of displaced individuals from a particular country arrive in a community [25]. Similarly, a mass gathering can typically be defined as the presence of at least 1000 people at a particular location for a specific amount of time, but it can also involve events that are attended by enough people to strain the resources of the host community in which they are held [26].

2.1. Jordan

Throughout its history, Jordan has experienced several mass influxes of displaced persons and refugees from Palestine, Lebanon, Kuwait, Iraq, and, most recently, Syria [27]. The Syrian Civil War has forced more than 1.2 million Syrians to flee to neighboring Jordan, but just over 620,000 are legally registered as refugees [28,29]. The Zaatari refugee camp, which is located just 12 km from the Jordan-Syria border, has become the fourth largest Jordanian city in terms of the population [30]. However, the majority of Syrian refugees do not live in refugee camps, instead choosing to reside in rural communities in the northern governorates of Irbid and Mafraq as well as in urban settings in the capital of Amman [31]. Syrian refugees were initially allowed access to free healthcare in Jordanian public hospitals, but the increasing burden on the public healthcare system resulted in revised policies that required Syrian refugees to pay unsubsidized healthcare rates [32,33]. In 2019, the Jordanian government reversed its health policy towards Syrian refugees, granting them access to subsidized healthcare once again [34].

In recent years, the public health epidemiological profile of refugee populations has shifted away from communicable diseases, as illustrated by the increasing non-communicable disease burden suffered by Syrian refugees in Jordan [35]. Among Syrian refugees, non-communicable diseases such as cancer have constrained the tertiary healthcare sector in Jordan [36]. Although no major infectious disease epidemic has occurred in Jordan, an increasing number of outbreaks have appeared among both the Jordanian and Syrian communities [37]. Cases of hepatitis A, leishmaniasis, and tuberculosis have occurred frequently in refugee camps, and polio outbreaks in neighboring countries have put Jordan at increased risk, which was mitigated with a nation-wide immunization program [38,39,40].

2.2. Saudi Arabia

Each year, millions of people from around the world arrive in the city of Mecca to perform either the greater pilgrimage (Hajj), which is performed at a certain time of the lunar year or the lesser pilgrimage (Umrah), which can be performed on a year-round basis [41]. Both types of pilgrimages involve mass gathering events, but the number of Hajj pilgrims far surpasses the number of Umrah pilgrims at any given time, as the five-day Hajj season causes the population of Mecca to triple as more than 2 million pilgrims descend upon the city [42]. Although the Umrah can be completed in a few hours, international pilgrims often take advantage of the two-week Umrah visa to visit other holy sites within the country [43].

A combination of the hot desert climate, physical fatigue, and crowded conditions makes pilgrims much more susceptible to contracting an infectious disease, especially acute respiratory infections [44]. Moreover, the fact that the Hajj is based on a lunar calendar means that it moves forward by 10 to 11 days each year, causing extra challenges based on whether it coincides in the hot summer months or during influenza season in the Northern hemisphere [42]. Increasing global temperatures due to climate change are only expected to exacerbate heat-related illnesses, including heat-stroke and heat exhaustion, among Hajj pilgrims [45].

From a historical perspective, the Hajj has been affected by a number of outbreaks involving various meningococcal diseases in 1987, 2000, and 2001 [46]. In addition, gastroenteritis and diarrhea feature prominently among pilgrims, with rates of prevalence ranging between 2% and 23% [47]. During the 2011 to 2013 Hajj seasons, a study of fecal samples from pilgrims suffering from diarrheal illness found that bacteria were the most common foodborne pathogens, comprising Salmonella spp., Shigella, and E. coli [48]. Among pilgrims returning from the Hajj, increased acquisition rates of multi-drug resistant Salmonella spp., E. coli, and A. baumannii were observed [49,50].

3. Distribution of Bats and Associated Pathogens

Bats belong to the diverse order Chiroptera, comprising over 1300 species that can be found on every continent except Antarctica [51]. Although they play an integral role in pest control, pollination, and seed dispersal, bats are hosts to a diverse number of viruses with high zoonotic potential and frequent spill over into human populations [52,53,54]. In fact, bats are known to be the natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses, with three Rhinolophus species (R. macrotis, R. pearsoni, and R. pussilus) demonstrating a high prevalence of SARS-CoV antibodies [55]. It is hypothesized that bats act as major viral reservoirs due to dampened inflammation, which allows viral infections to persist asymptomatically, high interferon levels, which limit viral replication, and a highly similar major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC II) human leukocyte antigen DR isotype (HLA-DR), which facilitates cross-species zoonotic infection [56,57].

A dearth of information exists in the context of viral surveillance of bats in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, and the wider Eastern Mediterranean region [58]. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of bat species that have been reported in Jordan and Saudi Arabia based on the published literature, while Table 1 lists the species of bats found in Jordan and Saudi Arabia along with their associated viral pathogens worldwide. Pipistrellus kuhli, which is found in both Jordan and Saudi Arabia, is of particular interest as a reservoir for a number of viral pathogens, resides in urban areas, and often comes into close contact with humans [59]. Rousettus aegyptiacus is also resident in Jordan and Saudi Arabia and has been previously been reported to be infected with the Lleida bat lyssavirus [60].

Figure 1.

Distribution of bat species in (a) Jordan and (b) Saudi Arabia.

3.1. Jordan

Bats constitute the largest diversity of mammalian species in Jordan, comprising at least 24 species from 8 families representing almost half of all bat species recorded in the Middle East and Egypt [61]. There is very little information about the pathogens harbored by Jordanian bats. In Europe, Eptesicus serotinus is responsible for human and animal exposure to the European bat 1 lyssavirus (EBLV-1) [62,63]. Other bat species known to carry lyssaviruses are Miniopterus schreibersii (a reservoir that sustains EBLV-1 transmission in multispecies bat populations), Myotis capaccinii (a regional migrant), and Rhinolophus ferrumequinum are also found in Jordan [64,65]. Coronaviruses have also been associated with several bat species native to Jordan (Table 1).

3.2. Saudi Arabia

There is a dearth of research on the bats of Saudi Arabia, and bats are considered to be a rare sight in the country, particularly in its central desert region [66]. Nonetheless, at least 15 species of bats from 8 families have been recorded in Saudi Arabia, including Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, and Riyadh [66]. MERS-CoV has been isolated from Rhinopoma hardwickii as well as Taphozous perforatus, and a number of other species native to Saudi Arabia have been previously associated with a range of coronaviruses as well as EBLV-1 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bat species native to Jordan and Saudi Arabia along with their worldwide associated pathogens. A dot indicates that this bat species has been recorded in the country.

Although they can be sources of viral diseases, little is known about bats and the extent of their contact with human populations in Jordan and Saudi Arabia. It has been observed that bat guano, the excrement of bats, is used as a source of natural fertilizer by farmers in a local context, as evidenced by the collection of guano from caves in Northern Jordan [101]. Consequently, future work should continue to investigate the molecular epidemiology of different virus isolates to improve our understanding of zoonotic viral diseases in humans and animals.

5. Compliance with the International Health Regulations

The International Health Regulations (IHR), first issued in 1959 and substantially revised in 2005, are an international piece of legislation dedicated to preventing and controlling the international spread of infectious disease. Before their revision, the IHR were constrained to a narrow scope of the same three infectious diseases, i.e., cholera, plague, and yellow fever, that were addressed at the 1st International Sanitary Conference in 1851 [184]. The process of modernizing the IHR, which formally began in 1995, was repeatedly delayed due to concerns of its effects on global trade, especially those governed by the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements [185]. Upon the completion of its revision in 2005, the update IHR maintained its mission of security without unnecessary interference to international traffic and trade, but it shifted the scope of health conditions to cover any “public health emergency of international concern” [184,185]. The updated IHR granted the World Health Organization (WHO) with the authority of making “temporary and standing recommendations for national health measures”, requiring “member states to maintain capacity for surveillance and response”, and allowing the WHO to “access and use non-governmental sources of surveillance information” [184,185].

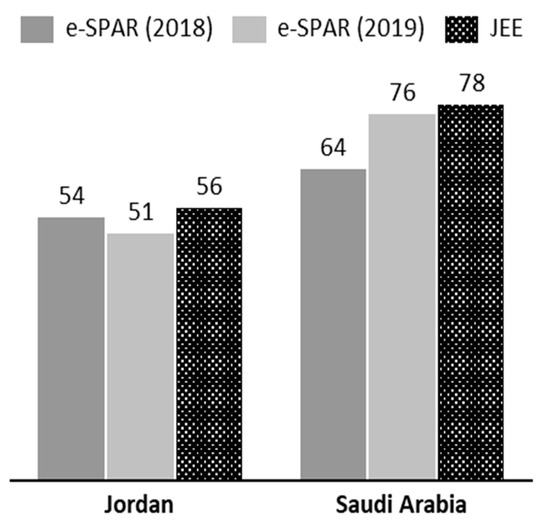

Despite these powers, ensuring the compliance of member states with the IHR remains a difficult task for the WHO, and a wide variation in levels of IHR compliance exists between member states [186]. Using the indices developed by Kandel et al. (2020), the operational readiness capacities for Jordan and Saudi Arabia were investigated [186]. As illustrated in Figure 2, there is some discrepancy between the scores given by the WHO in their Joint External Evaluation (JEE) mission reports and those self-reported via the Electronic State Parties Self-Assessment Annual Reporting Tool (e-SPAR). The JEE is carried out by a WHO mission, while the e-SPAR scores are assessed by the country itself. The low self-assessment score could be due to a lack of full understanding of capacity indicators and scores. The JEE mission report was undertaken in 2016 for Jordan (https://www.who.int/ihr/publications/WHO-WHE-CPI-2017.1/en/) and in 2017 for Saudi Arabia (https://www.who.int/ihr/publications/WHO-WHE-CPI-2017.25.report/en/). Saudi Arabia was given a score of 78 by the JEE mission in 2017, but it gave itself scores of 64 in 2018 and 76 in 2019. It is worth noting that the e-SPAR assessments are self-reported and not independently verified by the WHO. Taking a closer look at the capacity indices (Table 2), several of Jordan’s capacities are ranked at 3 due to poor decentralization, with capacities at the governorate and district levels in need of consolidation. In contrast, Saudi Arabia’s capacities are scored at 4, indicating a functional capability at both the national and sub-national levels [186].

Figure 2.

Operational readiness index as reported via the Electronic State Parties Self-Assessment Annual Reporting Tool (e-SPAR) in 2018 and 2019 and as observed by the WHO’s Joint External Evaluation (JEE) mission reports. [Level 1 ≤ 20 (very little capacity), Level 2 ≤ 40 (Little capacity), Level 3 ≤ 60 (Moderate Capacity), Level 4 ≤ 80 (High Capacity), Level 5 < 80 (Well Advanced Capacity)].

Table 2.

Joint External Evaluation (JEE) mission report scores across five capacity indices for Jordan and Saudi Arabia.

One of the most important IHR pillars is disease surveillance, which is defined as the ongoing systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of data to disseminate relevant findings to key public health stakeholders, as it is essential for the proper functioning of any national healthcare system [187]. To improve disease surveillance capacities, the Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP), which is hosted by each country’s Ministry of Health (MoH), aims to train an international and interconnected cadre of field epidemiologists to better contain outbreaks before they progress into full-blown epidemics [188]. In terms of the COVID-19 pandemic, the FETPs in the Eastern Mediterranean region, including those in Jordan and Saudi Arabia, actively participated in airport surveillance and public communication efforts [189].

5.1. Jordan

In partnership with the WHO, the MoH has implemented a public health surveillance framework that covers over 250 primary and secondary healthcare institutions across Jordan and includes the continuous training of hundreds of health professionals [190]. Correspondingly, a review mission carried out by WHO found that a consolidated Notifiable Disease Surveillance System was the main attribute of Jordan’s health information system [191]. In contrast, a survey of 223 Jordanian physicians in public hospitals found that the majority had not been trained in health surveillance nor filled a report for notifiable diseases, as disease notification was not enforced in Jordanian hospitals [192].

The FETP in Jordan was established in 1998 and is housed within the MoH, where it has trained dozens of physicians in the fields of disease surveillance and outbreak investigation [193]. However, the focus of Jordan FETP surveillance has mostly centered on non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity [194]. As a consequence of implementing the FETP, Jordan is a rarity in the region in that it meets the international standard of one field epidemiologist for every 200,000 people [193]. With regard to the Syrian crisis, the FETP has established a system for reporting the health of Syrian refugees seeking care at public hospitals, thus allowing the MoH to communicate key findings to international organizations every month [193]. In addition, the National Tuberculosis (TB) Program in Jordan detects and treats the disease among Syrian refugee communities, the members of which suffered from a disproportionately higher rate of TB compared to the rest of Jordan’s population [195]. Infectious and parasitic agents were the second most common causes of skin diseases among 799 Syrian refugees profiled as part of an international field-mission assessment [196].

5.2. Saudi Arabia

During the annual Hajj, healthcare is provided by the MoH to pilgrims free of charge, although some pilgrims also have access to the physicians accompanying their tour group [197]. As soon as the Hajj season ends, the MoH seeks technical consultations from international public health agencies and begins preparing for next year’s Hajj [198]. In 2012, the Saudi Arabian government established the Global Center for Mass Gathering Medicine to develop its health infrastructure in the context of pilgrimage and enhance research in the emerging field of mass gathering medicine [199]. Like Jordan, Saudi Arabia has also established its own FETP program in 1989 as a joint effort between the MoH and King Saudi University, and it is the only program of its kind in the Gulf Arab states [200,201]. With regard to infectious disease, major health risks to pilgrims include bat-borne diseases such as the coronaviruses [202].

6. Conclusions

As frequent hosts of mass gathering and mass influx events, Jordan and Saudi Arabia are presented with significant public health challenges. The ongoing COVID-19 outbreak is evidence that mass gatherings have the potential to substantially amplify the spread of disease, propelling its reach far and wide. In fact, Jordan experienced a surge in COVID-19 cases after a mass gathering during a wedding, in which 21.7% of attendees were infected [203]. As developing countries, Jordan and Saudi Arabia still have much to achieve in terms of their disease surveillance, biosecurity, and biosafety capabilities. Moreover, the presence of bat species that have been associated with dangerous pathogens highlights the ongoing threat of spillover and host switching into human populations. These emerging pathogens often switch hosts by changes in behavior or socioeconomic, environmental, or ecologic characteristics of the hosts. Further investigation is required to determine the level of risk posed by bat-borne viral infections in both countries.

7. Recommendations and Future Directions

Actions are needed to prepare for future pandemics, and these actions rely mainly on communities’ preparation and public health measures through the improvement of healthcare, emergency planning, education, and economic systems. Establishing well-designed education and training programs for healthcare workers is key for the implementation of reliable and sustainable practices during outbreaks. Countries need to consolidate their medical stockpiles ahead of any future disease outbreaks to avoid any shortages, which was a common issue in many countries during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, ongoing international collaboration is necessary for the development and effective distribution of vaccines. In addition, unified actions on travel restrictions and safety guidelines will also assist in the worldwide control of the disease. Finally, building a strong international collaborative effort is recommended to strengthen global disease surveillance networks, employ and enhance biosecurity management capacity, and promote a One Health concept.

Author Contributions

L.N.A.-E. initiated the review. L.N.A.-E., A.H.T., M.A.A., G.W., D.A.M., L.M.M., I.H.B. and A.R.F. collected and reviewed the scientific literature resources. L.N.A.-E. wrote the draft manuscript and all authors contributed to the final version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the Department of Environment and Rural Affairs Grant SE0431/SE0433 and the European Union Horizon 2020-funded Research Infrastructure Grant “European Virus Archive Global (EVAg)” under grant agreement number (871029).

Acknowledgments

The authors also would like to express their gratitude to Jordan University and Science and Technology (JUST, Irbid, Jordan) and Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA, Weybridge, Surrey, KT15 3NB, UK) for providing administrative and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Henig, R.M. Experts Warned of a Pandemic Decades Ago. Why Weren’t We Ready? Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/04/experts-warned-pandemic-decades-ago-why-not-ready-for-coronavirus/ (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Fauci, A.S.; Lane, H.C.; Redfield, R.R. Covid-19 - Navigating the uncharted. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1268–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Doorn, H.R. Emerging infectious diseases. Medicine (United Kingdom) 2014, 42, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, J.N.S.; Desai, M.A.; Levy, K.; Bates, S.J.; Liang, S.; Naumoff, K.; Scott, J.C. Environmental determinants of infectious disease: A framework for tracking causal links and guiding public health research. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, J.E.; Richt, J.A.; Mackenzie, J.S. Introduction: Conceptualizing and partitioning the emergence process of zoonotic viruses from wildlife to humans. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2007, 315, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, D.A.; Banyard, A.C.; McElhinney, L.M.; Freuling, C.M.; Finke, S.; de Lamballerie, X.; Müller, T.; Fooks, A.R. The lyssavirus host-specificity conundrum—Rabies virus—The exception not the rule. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2018, 28, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, P.L.; Firth, C.; Conte, J.M.; Williams, S.H.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.M.; Anthony, S.J.; Ellison, J.A.; Gilbert, A.T.; Kuzmin, I.V.; Niezgoda, M.; et al. Bats are a major natural reservoir for hepaciviruses and pegiviruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 8194–8199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.C.Y.; Lau, S.K.P.; Huang, Y.; Yuen, K.Y. Coronavirus diversity, phylogeny and interspecies jumping. Exp. Biol. Med. 2009, 234, 1117–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisher, C.H.; Childs, J.E.; Field, H.E.; Holmes, K.V.; Schountz, T. Bats: Important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2006, 19, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, J.F.; Corman, V.M.; Müller, M.A.; Maganga, G.D.; Vallo, P.; Binger, T.; Gloza-Rausch, F.; Rasche, A.; Yordanov, S.; Seebens, A.; et al. Bats host major mammalian paramyxoviruses. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, A.D.; Hayman, D.T.S.; O’Shea, T.J.; Cryan, P.M.; Gilbert, A.T.; Pulliam, J.R.C.; Mills, J.N.; Timonin, M.E.; Willis, C.K.R.; Cunningham, A.A.; et al. A comparison of bats and rodents as reservoirs of zoonotic viruses: Are bats special? Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20122753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollentze, N.; Streicker, D.G. Viral zoonotic risk is homogenous among taxonomic orders of mammalian and avian reservoir hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 9423–9430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peel, A.J.; Wells, K.; Giles, J.; Boyd, V.; Burroughs, A.; Edson, D.; Crameri, G.; Baker, M.L.; Field, H.; Wang, L.F.; et al. Synchronous shedding of multiple bat paramyxoviruses coincides with peak periods of Hendra virus spillover. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plowright, R.K.; Peel, A.J.; Streicker, D.G.; Gilbert, A.T.; McCallum, H.; Wood, J.; Baker, M.L.; Restif, O. Transmission or Within-Host Dynamics Driving Pulses of Zoonotic Viruses in Reservoir–Host Populations. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plowright, R.K.; Eby, P.; Hudson, P.J.; Smith, I.L.; Westcott, D.; Bryden, W.L.; Middleton, D.; Reid, P.A.; McFarlane, R.A.; Martin, G.; et al. Ecological dynamics of emerging bat virus spillover. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 282, 20142124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montecino-Latorre, D.; Goldstein, T.; Gilardi, K.; Wolking, D.; Van Wormer, E.; Kazwala, R.; Ssebide, B.; Nziza, J.; Sijali, Z.; Cranfield, M.; et al. Reproduction of East-African bats may guide risk mitigation for coronavirus spillover. One Health Outlook 2020, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannan, G. Communicable diseases in the Mediterranean region. Electron. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2018, 29, 164–170. [Google Scholar]

- Abubakar, A.; Malik, M.; Pebody, R.; Elkholy, A.; Khan, W.; Bellos, A.; Mala, P. Burden of acute respiratory disease of epidemic and pandemic potential in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region: A literature review. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2016, 22, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.R.; Mahjour, J. Preparedness for ebola: Can it transform our current public health system? East. Mediterr. Health J. 2016, 22, 566–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokdad, A.H.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Daoud, F.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Moradi-Lakeh, M.; Khalil, I.; Afshin, A.; Tuffaha, M.; Charara, R.; Barber, R.M.; et al. Health in times of uncertainty in the eastern Mediterranean region, 1990–2013: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e704–e713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. COVID-19 in the Eastern Mediterranean Region and Saudi Arabia: Prevention and therapeutic strategies. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, H.H.P.; Jakab, Z.; Bartovic, J.; D’Anna, V.; Severoni, S. Refugee and migrant health in the COVID-19 response. Lancet 2020, 395, 1237–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: An overview of their replication and pathogenesis. In Coronaviruses: Methods and Protocols; Maier, H., Bickerton, E., Britton, P., Eds.; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1282, pp. 1–23. ISBN 9781493924387. [Google Scholar]

- Memish, Z.A.; Steffen, R.; White, P.; Dar, O.; Azhar, E.I.; Sharma, A.; Zumla, A. Mass gatherings medicine: Public health issues arising from mass gathering religious and sporting events. Lancet 2019, 393, 2073–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, G.; Desmet, E. Essential Texts on European and International Asylum and Migration Law and Policy; Gompel & Svacina: Reebokweg, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Memish, Z.A.; Al-Rabeeah, A.A. Public health management of mass gatherings: The saudi arabian experience with MERS-CoV. Bull. World Health Organ. 2013, 91, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshoubaki, W. The Dynamics of Population Pressure in Jordan: A Focus on Syrian Refugees. In Syrian Crisis, Syrian Refugees; Beaujouan, J., Rasheed, A., Eds.; Palgrave Pivot: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Achilli, L. Syrian Refugees in Jordan: A Reality Check. Migr. Policy Cent. Eur. Univ. Inst. 2015, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alshoubaki, W. A synopsis of the jordanian governance system in the management of the syrian refugee crisis. J. Intercult. Stud. 2018, 39, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maani, N. From refugee camp to resilient city: Zaatari refugee camp, Jordan. Footprint 2016, 2016, 145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Tal, R.S.; Ahmad Ghanem, H.H. Impact of the Syrian crisis on the socio-spatial transformation of Eastern Amman, Jordan. Front. Archit. Res. 2019, 8, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akik, C.; Ghattas, H.; Mesmar, S.; Rabkin, M.; El-Sadr, W.M.; Fouad, F.M. Host country responses to non-communicable diseases amongst Syrian refugees: A review. Confl. Health 2019, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNatt, Z.Z.; Freels, P.E.; Chandler, H.; Fawad, M.; Qarmout, S.; Al-Oraibi, A.S.; Boothby, N. “What’s happening in Syria even affects the rocks”: A qualitative study of the Syrian refugee experience accessing noncommunicable disease services in Jordan. Confl. Health 2019, 13, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Rescue Committee. Public Health access and Health Seeking Behaviors of Syrian Refugees in Jordan. Available online: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/72211 (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Doocy, S.; Lyles, E.; Roberton, T.; Akhu-Zaheya, L.; Oweis, A.; Burnham, G. Prevalence and care-seeking for chronic diseases among Syrian refugees in Jordan. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, P.; Khalifa, A.; Mateen, F.J. Cancer in refugees in Jordan and Syria between 2009 and 2012: Challenges and the way forward in humanitarian emergencies. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e290–e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshidi, M.M.; Hijjawi, M.Q.B.; Jeriesat, S.; Eltom, A. Syrian refugees and Jordan’s health sector. Lancet 2013, 382, 206–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farag, N.H.; Wannemuehler, K.; Weldon, W.; Arbaji, A.; Belbaisi, A.; Khuri-Bulos, N.; Ehrhardt, D.; Surour, M.R.; ElhajQasem, N.S.; Al-Abdallat, M.M. Estimating population immunity to poliovirus in Jordan’s high-risk areas. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2019, 16, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, E.; Diaz, M.; Maina, A.G.K.; Brennan, M. Displaced populations due to humanitarian emergencies and its impact on global eradication and elimination of vaccine-preventable diseases. Confl. Health 2016, 10, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimer, N.A. A Review on Emerging and Reemerging of Infectious Diseases in Jordan: The Aftermath of the Syrian Crises. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2018, 2018, 8679174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatrad, A.R.; Sheikh, A. Erratum: Hajj: Journey of a lifetime (British Medical Journal (2005) 330 (133–137)). Br. Med. J. 2005, 331, 442. [Google Scholar]

- Memish, Z.A.; Stephens, G.M.; Steffen, R.; Ahmed, Q.A. Emergence of medicine for mass gatherings: Lessons from the Hajj. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yezli, S.; Yassin, Y.M.; Awam, A.H.; Attar, A.A.; Al-Jahdali, E.A.; Alotaibi, B.M. Umrah. An opportunity for mass gatherings health research. Saudi Med. J. 2017, 38, 868–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Q.A.; Arabi, Y.M.; Memish, Z.A. Health risks at the Hajj. Lancet 2006, 367, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoety, D.A.; El-Bakri, N.K.; Almowalld, W.O.; Turkistani, Z.A.; Bugis, B.H.; Baseif, E.A.; Melbari, M.H.; AlHarbi, K.; Abu-Shaheen, A. Characteristics of Heat Illness during Hajj: A Cross-Sectional Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5629474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.A. Meningococcal Disease and Travel. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautret, P.; Benkouiten, S.; Sridhar, S.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Diarrhea at the Hajj and Umrah. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2015, 13, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd El Ghany, M.; Alsomali, M.; Almasri, M.; Padron Regalado, E.; Naeem, R.; Tukestani, A.H.; Asiri, A.; Hill-Cawthorne, G.A.; Pain, A.; Memish, Z.A. Enteric infections circulating during Hajj seasons, 2011–2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 1640–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaitan, A.O.; Dia, N.M.; Gautret, P.; Benkouiten, S.; Belhouchat, K.; Drali, T.; Parola, P.; Brouqui, P.; Memish, Z.; Raoult, D.; et al. Acquisition of extended-spectrum cephalosporin- and colistin-resistant Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Newport by pilgrims during Hajj. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2015, 45, 600–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leangapichart, T.; Gautret, P.; Griffiths, K.; Belhouchat, K.; Memish, Z.; Raoult, D.; Rolain, J.M. Acquisition of a high diversity of bacteria during the Hajj pilgrimage, including Acinetobacter baumannii with blaOXA-72 and Escherichia coli with blaNDM-5 carbapenemase genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5942–5948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, M.B.; Simmons, N.B. Bats: A World of Science and Mystery, Fenton, Simmons; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, T.J.; Cryan, P.M.; Cunningham, A.A.; Fooks, A.R.; Hayman, D.T.S.; Luis, A.D.; Peel, A.J.; Plowright, R.K.; Wood, J.L.N. Bat flight and zoonotic viruses. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, T.H.; Braun De Torrez, E.; Bauer, D.; Lobova, T.; Fleming, T.H. Ecosystem services provided by bats. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2011, 1223, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olival, K.; Hosseini, P.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Nature, N.R.-; 2017, U. Host and viral traits predict zoonotic spillover from mammals. Nature 2017, 546, 646–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menachery, V.D.; Yount, B.L.; Debbink, K.; Agnihothram, S.; Gralinski, L.E.; Plante, J.A.; Graham, R.L.; Scobey, T.; Ge, X.Y.; Donaldson, E.F.; et al. A SARS-like cluster of circulating bat coronaviruses shows potential for human emergence. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 1508–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, A. On the bat’s back I do fly. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Baker, M.L.; Kulcsar, K.; Misra, V.; Plowright, R.; Mossman, K. Novel Insights Into Immune Systems of Bats. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, K.L.; Hamel, L.; Alhmoud, N.; Ali, S.; Bilgin, R.; Sidamonidze, K.; Urushadze, L.; Karesh, W.; Olival, K.J. Bat research networks and viral surveillance: Gaps and opportunities in western Asia. Viruses 2019, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelli, D.; Moreno, A.; Lavazza, A.; Bresaola, M.; Canelli, E.; Boniotti, M.B.; Cordioli, P. Identification of Mammalian Orthoreovirus Type 3 in Italian Bats. Zoonoses Public Health 2013, 60, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellenberg, G.J.; Audry, L.; Rønsholt, L.; Van der Poel, W.H.M.; Bruschke, C.J.M.; Bourhy, H. Presence of European bat lyssavirus RNAs in apparently healthy Rousettus aegyptiacus bats. Arch. Virol. 2002, 147, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amr, Z.S.; Abu Baker, M.A.; Botros Qumsiyeh, M. Bat Diversity and Conservation in Jordan. Turkish J. Zool. 2006, 30, 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Eggerbauer, E.; Pfaff, F.; Finke, S.; Höper, D.; Beer, M.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Nolden, T.; Teifke, J.-P.; Müller, T.; Freuling, C.M. Comparative analysis of European bat lyssavirus 1 pathogenicity in the mouse model. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, S.; Ibáñez, C.; Juste, J.; Echevarria, J.E. EBLV1 circulation in natural bat colonies of Eptesicus serotinus: A six year survey. Dev. Biol. (Basel) 2006, 125, 257–261. [Google Scholar]

- Papadatou, E.; Butlin, R.K.; Altringham, J.D. Seasonal Roosting Habits and Population Structure of the Long-fingered Bat Myotis capaccinii in Greece. J. Mammal. 2008, 89, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons-Salort, M.; Serra-Cobo, J.; Jay, F.; López-Roig, M.; Lavenir, R.; Guillemot, D.; Letort, V.; Bourhy, H.; Opatowski, L. Insights into Persistence Mechanisms of a Zoonotic Virus in Bat Colonies Using a Multispecies Metapopulation Model. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NADER, I.A. On the bats (Chiroptera) of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Zool. 1975, 176, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.A.; Mishra, N.; Olival, K.J.; Fagbo, S.F.; Kapoor, V.; Epstein, J.H.; AlHakeem, R.; Al Asmari, M.; Islam, A.; Kapoor, A.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Bats, Saudi Arabia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1819–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcês, A.; Correia, S.; Amorim, F.; Pereira, J.E.; Igrejas, G.; Poeta, P. First report on extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia coli from European free-tailed bats (Tadarida teniotis) in Portugal: A one-health approach of a hidden contamination problem. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 370, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markotter, W.; Monadjem, A.; Nel, L.H. Antibodies against Duvenhage virus in insectivorous bats in Swaziland. J. Wildl. Dis. 2013, 49, 1000–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jánoska, M.; Vidovszky, M.; Molnár, V.; Liptovszky, M.; Harrach, B.; Benko, M. Novel adenoviruses and herpesviruses detected in bats. Vet. J. 2011, 189, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amman, B.R.; Bird, B.H.; Bakarr, I.A.; Bangura, J.; Schuh, A.J.; Johnny, J.; Sealy, T.K.; Conteh, I.; Koroma, A.H.; Foday, I.; et al. Isolation of Angola-like Marburg virus from Egyptian rousette bats from West Africa. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amman, B.R.; Carroll, S.A.; Reed, Z.D.; Sealy, T.K.; Balinandi, S.; Swanepoel, R.; Kemp, A.; Erickson, B.R.; Comer, J.A.; Campbell, S.; et al. Seasonal Pulses of Marburg Virus Circulation in Juvenile Rousettus aegyptiacus Bats Coincide with Periods of Increased Risk of Human Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, J.F.; Gloza-Rausch, F.; Glende, J.; Corman, V.M.; Muth, D.; Goettsche, M.; Seebens, A.; Niedrig, M.; Pfefferle, S.; Yordanov, S.; et al. Genomic Characterization of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Related Coronavirus in European Bats and Classification of Coronaviruses Based on Partial RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Gene Sequences. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 11336–11349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markotter, W.; Geldenhuys, M.; Jansen van Vuren, P.; Kemp, A.; Mortlock, M.; Mudakikwa, A.; Nel, L.; Nziza, J.; Paweska, J.; Weyer, J. Paramyxo- and Coronaviruses in Rwandan Bats. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2019, 4, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ar Gouilh, M.; Puechmaille, S.J.; Diancourt, L.; Vandenbogaert, M.; Serra-Cobo, J.; Lopez Roïg, M.; Brown, P.; Moutou, F.; Caro, V.; Vabret, A.; et al. SARS-CoV related Betacoronavirus and diverse Alphacoronavirus members found in western old-world. Virology 2018, 517, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, F.; Edenborough, K.M.; Toffoli, R.; Culasso, P.; Zoppi, S.; Dondo, A.; Robetto, S.; Rosati, S.; Lander, A.; Kurth, A.; et al. Coronavirus and paramyxovirus in bats from Northwest Italy. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Cobo, J.; Amengual, B.; Carlos Abellán, B.; Bourhy, H. European bat Lyssavirus infection in Spanish bat populations. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noguchi, K.; Kuwata, R.; Shimoda, H.; Mizutani, T.; Hondo, E.; Maeda, K. The complete genomic sequence of Rhinolophus gammaherpesvirus 1 isolated from a greater horseshoe bat. Arch. Virol. 2019, 164, 317–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pauly, M.; Pir, J.B.; Loesch, C.; Sausy, A.; Snoeck, C.J.; Hübschen, J.M.; Muller, C.P. Novel alphacoronaviruses and paramyxoviruses cocirculate with type 1 and severe acute respiratory system (SARS)-related betacoronaviruses in synanthropic bats of Luxembourg. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01326-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihtarič, D.; Hostnik, P.; Steyer, A.; Grom, J.; Toplak, I. Identification of SARS-like coronaviruses in horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus hipposideros) in Slovenia. Arch. Virol. 2010, 155, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, N.; Fagbo, S.F.; Alagaili, A.N.; Nitido, A.; Williams, S.H.; Ng, J.; Lee, B.; Durosinlorun, A.; Garcia, J.A.; Jain, K.; et al. A viral metagenomic survey identifies known and novel mammalian viruses in bats from Saudi Arabia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufkova, L.; Straková, P.; Širmarová, J.; Salát, J.; Moutelíková, R.; Chrudimský, T.; Bartonička, T.; Nowotny, N.; Růžek, D. Detection of Diverse Novel Bat Astrovirus Sequences in the Czech Republic. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015, 15, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Benedictis, P.; Marciano, S.; Scaravelli, D.; Priori, P.; Zecchin, B.; Capua, I.; Monne, I.; Cattoli, G. Alpha and lineage C betaCoV infections in Italian bats. Virus Genes 2014, 48, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.C.; Aegerter, J.N.; Allnutt, T.R.; MacNicoll, A.D.; Learmount, J.; Hutson, A.M.; Atterby, H. Bat population genetics and Lyssavirus presence in Great Britain. Epidemiol. Infect. 2011, 139, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robardet, E.; Borel, C.; Moinet, M.; Jouan, D.; Wasniewski, M.; Barrat, J.; Boué, F.; Montchâtre-Leroy, E.; Servat, A.; Gimenez, O.; et al. Longitudinal survey of two serotine bat (Eptesicus serotinus) maternity colonies exposed to EBLV-1 (European Bat Lyssavirus type 1): Assessment of survival and serological status variations using capture-recapture models. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0006048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard-Meyer, E.; Dubourg-Savage, M.J.; Arthur, L.; Barataud, M.; Bécu, D.; Bracco, S.; Borel, C.; Larcher, G.; Meme-Lafond, B.; Moinet, M.; et al. Active surveillance of bat rabies in France: A 5-year study (2004–2009). Vet. Microbiol. 2011, 151, 390–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, V.; Jánoska, M.; Harrach, B.; Glávits, R.; Pálmai, N.; Rigó, D.; Sós, E.; Liptovszky, M. Detection of a novel bat gammaherpesvirus in Hungary. Acta Vet. Hung. 2008, 56, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, N.A.; Morón, S.V.; Berciano, J.M.; Nicolás, O.; López, C.A.; Juste, J.; Nevado, C.R.; Setién, Á.A.; Echevarría, J.E. Novel lyssavirus in bat, Spain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 793–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard-Meyer, E.; Beven, V.; Hirchaud, E.; Guillaume, C.; Larcher, G.; Robardet, E.; Servat, A.; Blanchard, Y.; Cliquet, F. Lleida Bat Lyssavirus isolation in Miniopterus schreibersii in France. Zoonoses Public Health 2019, 66, 254–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemenesi, G.; Kurucz, K.; Dallos, B.; Zana, B.; Földes, F.; Boldogh, S.; Görföl, T.; Carroll, M.W.; Jakab, F. Re-emergence of Lloviu virus in Miniopterus schreibersii bats, Hungary, 2016. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuzmin, I.V.; Niezgoda, M.; Franka, R.; Agwanda, B.; Markotter, W.; Beagley, J.C.; Urazova, O.Y.; Breiman, R.F.; Rupprecht, C.E. Possible emergence of West Caucasian bat virus in Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2008, 14, 1887–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Picard-Meyer, E.; Servat, A.; Robardet, E.; Moinet, M.; Borel, C.; Cliquet, F. Isolation of Bokeloh bat lyssavirus in Myotis nattereri in France. Arch. Virol. 2013, 158, 2333–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freuling, C.M.; Beer, M.; Conraths, F.J.; Finke, S.; Hoffmann, B.; Keller, B.; Kliemt, J.; Mettenleiter, T.C.; Mühlbach, E.; Teifke, J.P.; et al. Novel lyssavirus in Natterer’s bat, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1519–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibbelt, G.; Kurth, A.; Yasmum, N.; Bannert, M.; Nagel, S.; Nitsche, A.; Ehlers, B. Discovery of herpesviruses in bats. J. Gen. Virol. 2007, 88, 2651–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelli, D.; Papetti, A.; Sabelli, C.; Rosti, E.; Moreno, A.; Boniotti, M.B. Detection of coronaviruses in bats of various species in Italy. Viruses 2013, 5, 2679–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straková, P.; Dufkova, L.; Širmarová, J.; Salát, J.; Bartonička, T.; Klempa, B.; Pfaff, F.; Höper, D.; Hoffmann, B.; Ulrich, R.G.; et al. Novel hantavirus identified in European bat species Nyctalus noctula. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2017, 48, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Lelli, D.; De Sabato, L.; Zaccaria, G.; Boni, A.; Sozzi, E.; Prosperi, A.; Lavazza, A.; Cella, E.; Castrucci, M.R.; et al. Detection and full genome characterization of two beta CoV viruses related to Middle East respiratory syndrome from bats in Italy. Virol. J. 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lelli, D.; Prosperi, A.; Moreno, A.; Chiapponi, C.; Gibellini, A.M.; De Benedictis, P.; Leopardi, S.; Sozzi, E.; Lavazza, A. Isolation of a novel Rhabdovirus from an insectivorous bat (Pipistrellus kuhlii) in Italy. Virol. J. 2018, 15, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusi, M. Toscana Virus Epidemiology: From Italy to Beyond. Open Virol. J. 2010, 4, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schatz, J.; Fooks, A.R.; Mcelhinney, L.; Horton, D.; Echevarria, J.; Vázquez-Moron, S.; Kooi, E.A.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Müller, T.; Freuling, C.M. Bat Rabies Surveillance in Europe. Zoonoses Public Health 2013, 60, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Malabeh, A.; Kempe, S.; Henschel, H.V.; Hofmann, H.; Tobschall, H.J. The possibly hypogene karstic iron ore deposit of Warda near Ajloun (Northern Jordan), its mineralogy, geochemistry and historic mine. Acta Carsol. 2008, 37, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, K.; Peiris, J.S.M. Coronaviruses. In Clinical Virology, 3rd ed.; Richman, D., Whitley, R., Hayden, F., Eds.; ASM Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2009; pp. 1155–1171. [Google Scholar]

- AL-Eitan, L.N.; Alahmad, S.Z. Pharmacogenomics of genetic polymorphism within the genes responsible for SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility and the drug-metabolising genes used in treatment. Rev. Med. Virol. 2020, e2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, R.L.; Donaldson, E.F.; Baric, R.S. A decade after SARS: Strategies for controlling emerging coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 836–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Hoek, L. Human coronaviruses: What do they cause? Antivir. Ther. 2007, 12, 651–658. [Google Scholar]

- Paden, C.R.; Yusof, M.F.B.M.; Al Hammadi, Z.M.; Queen, K.; Tao, Y.; Eltahir, Y.M.; Elsayed, E.A.; Marzoug, B.A.; Bensalah, O.K.A.; Khalafalla, A.I.; et al. Zoonotic origin and transmission of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in the UAE. Zoonoses Public Health 2018, 65, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolles, M.; Donaldson, E.; Baric, R. SARS-CoV and emergent coronaviruses: Viral determinants of interspecies transmission. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2011, 1, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Liu, Y.; Lei, X.; Li, P.; Mi, D.; Ren, L.; Guo, L.; Guo, R.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, S.J.; Ojeda-Flores, R.; Rico-Chávez, O.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.M.; Rostal, M.K.; Epstein, J.H.; Tipps, T.; Liang, E.; Sanchez-Leon, M.; et al. Coronaviruses in bats from Mexico. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ithete, N.L.; Stoffberg, S.; Corman, V.M.; Cottontail, V.M.; Richards, L.R.; Schoeman, M.C.; Drosten, C.; Drexler, J.F.; Preiser, W. Close relative of human middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bat, South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1697–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Osail, A.M.; Al-Wazzah, M.J. The history and epidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome corona virus. Multidiscip. Respir. Med. 2017, 12, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Shi, Z.; Yu, M.; Ren, W.; Smith, C.; Epstein, J.H.; Wang, H.; Crameri, G.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Bats are natural reservoirs of SARS-like coronaviruses. Science (80-. ) 2005, 310, 676–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menachery, V.D.; Yount, B.L.; Sims, A.C.; Debbink, K.; Agnihothram, S.S.; Gralinski, L.E.; Graham, R.L.; Scobey, T.; Plante, J.A.; Royal, S.R.; et al. SARS-like WIV1-CoV poised for human emergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 3048–3053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Li, S.Y.; Yang, X.L.; Huang, H.M.; Zhang, Y.J.; Guo, H.; Luo, C.M.; Miller, M.; Zhu, G.; Chmura, A.A.; et al. Serological Evidence of Bat SARS-Related Coronavirus Infection in Humans, China. Virol. Sin. 2018, 33, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC MERS Symptoms & Complications|CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/about/symptoms.html (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Dong, E.; Du, H.; Gardner, L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 533–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Zhuang, Q.; Xu, L.; He, Q. A comparison of COVID-19, SARS and MERS. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killerby, M.E.; Biggs, H.M.; Midgley, C.M.; Gerber, S.I.; Watson, J.T. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus transmission. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katul, G.G.; Mrad, A.; Bonetti, S.; Manoli, G.; Parolari, A.J. Global convergence of COVID-19 basic reproduction number and estimation from early-time SIR dynamics. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arabi, Y.M.; Arifi, A.A.; Balkhy, H.H.; Najm, H.; Aldawood, A.S.; Ghabashi, A.; Hawa, H.; Alothman, A.; Khaldi, A.; Al Raiy, B. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 160, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd, H.A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) origin and animal reservoir. Virol. J. 2016, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, S.J.; Gilardi, K.; Menachery, V.D.; Goldstein, T.; Ssebide, B.; Mbabazi, R.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Liang, E.; Wells, H.; Hicks, A.; et al. Further evidence for bats as the evolutionary source of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. MBio 2017, 8, e00373-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumla, A.; Hui, D.S.; Perlman, S. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Lancet 2015, 386, 995–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, A.M.; van Boheemen, S.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Osterhaus, A.D.M.E.; Fouchier, R.A.M. Isolation of a Novel Coronavirus from a Man with Pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1814–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munster, V.J.; Adney, D.R.; Van Doremalen, N.; Brown, V.R.; Miazgowicz, K.L.; Milne-Price, S.; Bushmaker, T.; Rosenke, R.; Scott, D.; Hawkinson, A.; et al. Replication and shedding of MERS-CoV in Jamaican fruit bats (Artibeus jamaicensis). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eifan, S.A.; Nour, I.; Hanif, A.; Zamzam, A.M.M.; AlJohani, S.M. A pandemic risk assessment of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2017, 24, 1631–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.W.; Poon, L.L.M.; Gomaa, M.M.; Shehata, M.M.; Perera, R.A.P.M.; Zeid, D.A.; El Rifay, A.S.; Siu, L.Y.; Guan, Y.; Webby, R.J.; et al. MERS coronaviruses in dromedary camels, Egypt. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1049–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusken, C.B.; Ababneh, M.; Raj, V.S.; Meyer, B.; Eljarah, A.; Abutarbush, S.; Godeke, G.J.; Bestebroer, T.M.; Zutt, I.; Müller, M.A.; et al. Middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) serology in major livestock species in an affected region in Jordan, June to September 2013. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reusken, C.B.E.M.; Haagmans, B.L.; Müller, M.A.; Gutierrez, C.; Godeke, G.J.; Meyer, B.; Muth, D.; Raj, V.S.; De Vries, L.S.; Corman, V.M.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus neutralising serum antibodies in dromedary camels: A comparative serological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, R.A.; Wang, P.; Gomaa, M.R.; El-Shesheny, R.; Kandeil, A.; Bagato, O.; Siu, L.Y.; Shehata, M.M.; Kayed, A.S.; Moatasim, Y.; et al. Seroepidemiology for MERS coronavirus using microneutralisation and pseudoparticle virus neutralisation assays reveal a high prevalence of antibody in dromedary camels in Egypt, June 2013. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemida, M.; Perera, R.; Wang, P.; Alhammadi, M.; Siu, L.; Li, M.; Poon, L.; Saif, L.; Alnaeem, A.; Peiris, M. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus seroprevalence in domestic livestock in Saudi Arabia, 2010 to 2013. Eurosurveillance 2013, 18, 20659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, B.; Müller, M.A.; Corman, V.M.; Reusken, C.B.E.M.; Ritz, D.; Godeke, G.J.; Lattwein, E.; Kallies, S.; Siemens, A.; van Beek, J.; et al. Antibodies against MERS coronavirus in dromedaries, United Arab Emirates, 2003 and 2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.A.; Meyer, B.; Corman, V.M.; Al-Masri, M.; Turkestani, A.; Ritz, D.; Sieberg, A.; Aldabbagh, S.; Bosch, B.J.; Lattwein, E.; et al. Presence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus antibodies in Saudi Arabia: A nationwide, cross-sectional, serological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.C.; Nguyen, D.; Aden, B.; Al Bandar, Z.; Al Dhaheri, W.; Abu Elkheir, K.; Khudair, A.; Al Mulla, M.; El Saleh, F.; Imambaccus, H.; et al. Transmission of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infections in healthcare settings, abu dhabi. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif-Yakan, A.; Kanj, S.S. Emergence of MERS-CoV in the Middle East: Origins, Transmission, Treatment, and Perspectives. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jasser, F.S.; Nouh, R.M.; Youssef, R.M. Epidemiology and predictors of survival of MERS-CoV infections in Riyadh region, 2014–2015. J. Infect. Public Health 2019, 12, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdallat, M.M.; Payne, D.C.; Alqasrawi, S.; Rha, B.; Tohme, R.A.; Abedi, G.R.; Nsour, M.A.; Iblan, I.; Jarour, N.; Farag, N.H.; et al. Hospital-associated outbreak of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus: A serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, 1225–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khuri-Bulos, N.; Payne, D.C.; Lu, X.; Erdman, D.; Wang, L.; Faouri, S.; Shehabi, A.; Johnson, M.; Becker, M.M.; Denison, M.R.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus not detected in children hospitalized with acute respiratory illness in Amman, Jordan, March 2010 to September 2012. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doremalen, N.; Hijazeen, Z.S.K.; Holloway, P.; Al Omari, B.; McDowell, C.; Adney, D.; Talafha, H.A.; Guitian, J.; Steel, J.; Amarin, N.; et al. High Prevalence of Middle East Respiratory Coronavirus in Young Dromedary Camels in Jordan. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2017, 17, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, D.C.; Biggs, H.M.; Al-Abdallat, M.M.; Alqasrawi, S.; Lu, X.; Abedi, G.R.; Haddadin, A.; Iblan, I.; Alsanouri, T.; Nsour, M.A.; et al. Multihospital outbreak of a Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus deletion variant, Jordan: A molecular, serologic, and epidemiologic investigation. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, ofy095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, M.M.; Raj, S.V.; Shafei, M.; Ali, S.S.; Abdallh, S.M.; Gazo, M.; Nofal, S.; Lu, X.; Erdman, D.D.; Koopmans, M.P.; et al. Deletion variants of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus from humans, Jordan, 2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV). Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/middle-east-respiratory-syndrome-coronavirus-mers#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Zumla, A.; Memish, Z.A. Respiratory tract infections during the annual Hajj. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2013, 19, 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautret, P.; Benkouiten, S.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Memish, Z.A. Hajj-associated viral respiratory infections: A systematic review. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2016, 14, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.A.; Almasri, M.; Turkestani, A.; Al-Shangiti, A.M.; Yezli, S. Etiology of severe community-acquired pneumonia during the 2013 Hajj-part of the MERS-CoV surveillance program. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 25, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaraj, S.H.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Alzahrani, N.A.; Altwaijri, T.A.; Memish, Z.A. The impact of co-infection of influenza A virus on the severity of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus. J. Infect. 2017, 74, 521–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memish, Z.A.; Zumla, A.; Alhakeem, R.F.; Assiri, A.; Turkestani, A.; Al Harby, K.D.; Alyemni, M.; Dhafar, K.; Gautret, P.; Barbeschi, M.; et al. Hajj: Infectious disease surveillance and control. Lancet 2014, 383, 2073–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premila Devi, J.; Noraini, W.; Norhayati, R.; Chee Kheong, C.; Badrul, A.S.; Zainah, S.; Fadzilah, K.; Hirman, I.; Lokman Hakim, S.; Noor Hisham, A. Laboratory-confirmed case of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in Malaysia: Preparedness and response, April 2014. Eurosurveillance 2014, 19, 20797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Beckett, G.; Wiselka, M. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in pilgrims returning from the Hajj. BMJ 2015, 351, h5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautret, P.; Charrel, R.; Benkouiten, S.; Belhouchat, K.; Nougairede, A.; Drali, T.; Salez, N.; Memish, Z.A.; al Masri, M.; Lagier, J.C.; et al. Lack of MERS coronavirus but prevalence of influenza virus in French pilgrims after 2013 Hajj. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkouiten, S.; Charrel, R.; Belhouchat, K.; Drali, T.; Salez, N.; Nougairede, A.; Zandotti, C.; Memish, Z.A.; al Masri, M.; Gaillard, C.; et al. Circulation of Respiratory Viruses Among Pilgrims During the 2012 Hajj Pilgrimage. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautret, P.; Charrel, R.; Belhouchat, K.; Drali, T.; Benkouiten, S.; Nougairede, A.; Zandotti, C.; Memish, Z.A.; al Masri, M.; Gaillard, C.; et al. Lack of nasal carriage of novel corona virus (HCoV-EMC) in French Hajj pilgrims returning from the Hajj 2012, despite a high rate of respiratory symptoms. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, E315–E317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, H.; Barasheed, O.; Booy, R. Acute febrile respiratory infection symptoms in Australian Hajjis at risk of exposure to middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Med. J. Aust. 2013, 199, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koul, P.A.; Mir, H.; Saha, S.; Chadha, M.S.; Potdar, V.; Widdowson, M.A.; Lal, R.B.; Krishnan, A. Influenza not MERS CoV among returning Hajj and Umrah pilgrims with respiratory illness, Kashmir, north India, 2014–2015. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2017, 15, 45–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refaey, S.; Amin, M.M.; Roguski, K.; Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Uyeki, T.M.; Labib, M.; Kandeel, A. Cross-sectional survey and surveillance for influenza viruses and MERS-CoV among Egyptian pilgrims returning from Hajj during 2012–2015. Influenza Other Respi. Viruses 2017, 11, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Liu, F.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Lu, M.; Abudukadeer, A.; Wang, L.; Tian, F.; Zhen, W.; Yang, P.; et al. No MERS-CoV but positive influenza viruses in returning Hajj pilgrims, China, 2013–2015. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annan, A.; Owusu, M.; Marfo, K.S.; Larbi, R.; Sarpong, F.N.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y.; Amankwa, J.; Fiafemetsi, S.; Drosten, C.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; et al. High prevalence of common respiratory viruses and no evidence of Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus in Hajj pilgrims returning to Ghana, 2013. Trop. Med. Int. Heal. 2015, 20, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Bakhtiar, A.; Subarjo, M.; Aksono, E.B.; Widiyanti, P.; Shimizu, K.; Mori, Y. Screening for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus among febrile Indonesian Hajj pilgrims: A study on 28,197 returning pilgrims. J. Infect. Prev. 2018, 19, 236–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavarian, J.; Shafiei Jandaghi, N.Z.; Naseri, M.; Hemmati, P.; Dadras, M.; Gouya, M.M.; Mokhtari Azad, T. Influenza virus but not MERS coronavirus circulation in Iran, 2013–2016: Comparison between pilgrims and general population. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2018, 21, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdallat, M.M.; Rha, B.; Alqasrawi, S.; Payne, D.C.; Iblan, I.; Binder, A.M.; Haddadin, A.; Nsour, M.A.; Alsanouri, T.; Mofleh, J.; et al. Acute respiratory infections among returning Hajj pilgrims—Jordan, 2014. J. Clin. Virol. 2017, 89, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Memish, Z.A.; Assiri, A.; Almasri, M.; Alhakeem, R.F.; Turkestani, A.; Al Rabeeah, A.A.; Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Alzahrani, A.; Azhar, E.; Makhdoom, H.Q.; et al. Prevalence of MERS-CoV Nasal Carriage and Compliance With the Saudi Health Recommendations Among Pilgrims Attending the 2013 Hajj. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 210, 1067–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaij – Dirkzwager, M.; Timen, A.; Dirksen, K.; Gelinck, L.; Leyten, E.; Groeneveld, P.; Jansen, C.; Jonges, M.; Raj, S.; Thurkow, I.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infections in two returning travellers in the Netherlands, May 2014. Eurosurveillance 2014, 19, 20817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almasri, M.; Ahmed, Q.A.; Turkestani, A.; Memish, Z.A. Hajj abattoirs in Makkah: Risk of zoonotic infections among occupational workers. Vet. Med. Sci. 2019, 5, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakawi, A.; Rose, E.B.; Biggs, H.M.; Lu, X.; Mohammed, M.; Abdalla, O.; Abedi, G.R.; Alsharef, A.A.; Alamri, A.A.; Bereagesh, S.A.; et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Saudi Arabia, 2017–2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 2149–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Kafrawy, S.A.; Corman, V.M.; Tolah, A.M.; Al Masaudi, S.B.; Hassan, A.M.; Müller, M.A.; Bleicker, T.; Harakeh, S.M.; Alzahrani, A.A.; Alsaaidi, G.A.; et al. Enzootic patterns of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in imported African and local Arabian dromedary camels: A prospective genomic study. Lancet Planet. Health 2019, 3, e521–e528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwait News Agency (KUNA). Camel Slaughtering in Hajj Banned for Fear of Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.kuna.net.kw/ArticleDetails.aspx?id=2460041&language=en (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Zheng, J. SARS-coV-2: An emerging coronavirus that causes a global threat. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symptoms of Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- Li, G.; He, X.; Zhang, L.; Ran, Q.; Wang, J.; Xiong, A.; Wu, D.; Chen, F.; Sun, J.; Chang, C. Assessing ACE2 expression patterns in lung tissues in the pathogenesis of COVID-19. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 112, 102463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Chen, X.; Hu, T.; Li, J.; Song, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, P.; Liu, D.; Yang, J.; Holmes, E.C.; et al. A Novel Bat Coronavirus Closely Related to SARS-CoV-2 Contains Natural Insertions at the S1/S2 Cleavage Site of the Spike Protein. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, 2196–2203.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.W.; Kok, K.H.; Zhu, Z.; Chu, H.; To, K.K.W.; Yuan, S.; Yuen, K.Y. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xiao, X.; Wei, X.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Tan, H.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, J.; Liu, L. Composition and divergence of coronavirus spike proteins and host ACE2 receptors predict potential intermediate hosts of SARS-CoV-2. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boni, M.F.; Lemey, P.; Jiang, X.; Lam, T.T.; Perry, B.W.; Castoe, T.A.; Rambaut, A.; Robertson, D.L. Evolutionary origins of the SARS-CoV-2 sarbecovirus lineage responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Hughes, T.; Lee, M.-H.; Field, H.; Rovie-Ryan, J.J.; Sitam, F.T.; Sipangkui, S.; Nathan, S.; Ramirez, D.; Kumar, S.V.; et al. No Evidence of Coronaviruses or Other Potentially Zoonotic Viruses in Sunda pangolins (Manis javanica) Entering the Wildlife Trade via Malaysia. Ecohealth 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqutob, R.; Al Nsour, M.; Tarawneh, M.R.; Ajlouni, M.; Khader, Y.; Aqel, I.; Kharabsheh, S.; Obeidat, N. COVID-19 crisis in Jordan: Response, scenarios, strategies, and recommendations (Preprint). JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e19332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santucci, E. What Lies ahead as Jordan Faces the Fallout of COVID-19 - Atlantic Council. Available online: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/what-lies-ahead-as-jordan-faces-the-fallout-of-covid-19/ (accessed on 19 July 2020).

- El-Khatib, Z.; Al Nsour, M.; Khader, Y.S.; Abu Khudair, M. Mental health support in Jordan for the general population and for the refugees in the Zaatari camp during the period of COVID-19 lockdown. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawad, M.; Rawashdeh, F.; Parmar, P.K.; Ratnayake, R. Simple ideas to mitigate the impacts of the COVID-19 epidemic on refugees with chronic diseases. Confl. Health 2020, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yezli, S.; Khan, A. COVID-19 social distancing in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Bold measures in the face of political, economic, social and religious challenges. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2020, 37, 101692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, S.H.; Memish, Z.A. COVID-19: Preparing for superspreader potential among Umrah pilgrims to Saudi Arabia. Lancet 2020, 395, e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, S.H.; Memish, Z.A. Saudi Arabia’s drastic measures to curb the COVID-19 outbreak: Temporary suspension of the Umrah pilgrimage. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostin, L.O. International infectious disease law: Revision of the World Health Organization’s International Health Regulations. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2004, 291, 2623–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, D.P.; Gostin, L.O. The New International Health Regulations: An Historic Development for International Law and Public Health. J. Law Med. Ethics 2006, 34, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandel, N.; Chungong, S.; Omaar, A.; Xing, J. Health security capacities in the context of COVID-19 outbreak: An analysis of International Health Regulations annual report data from 182 countries. Lancet 2020, 395, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsubuga, P.; White, M.E.; Thacker, S.B.; Anderson, M.A.; Blount, S.B.; Broome, C.V.; Chiller, T.M.; Espitia, V.; Imtiaz, R.; Sosin, D.; et al. Chapter 53. Public Health Surveillance: A Tool for Targeting and Monitoring Interventions. In Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries, 2nd ed.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 997–1016. ISBN 0821361791. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, R.E.; Herrera, D.G.; Kelly, P.M. An evaluation of the global network of field epidemiology and laboratory training programmes: A resource for improving public health capacity and increasing the number of public health professionals worldwide. Hum. Resour. Health 2013, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nsour, M.; Bashier, H.; Al Serouri, A.; Malik, E.; Khader, Y.; Saeed, K.; Ikram, A.; Abdalla, A.M.; Belalia, A.; Assarag, B.; et al. The role of the global health development/eastern mediterranean public health network and the eastern mediterranean field epidemiology training programs in preparedness for COVID-19. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhali, S.A.; Abdallat, M.; Mabdalla, S.; Qaseer, B.A.; Khorma, R.; Malik, M.; Profili, M.C.; Rø, G.; Haskew, J. Design and implementation of a national public health surveillance system in Jordan. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2016, 88, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Comprehensive Assessment of Jordan’s Health Information System 2016. Available online: https://applications.emro.who.int/docs/9789290222583-eng.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Abdulrahim, N.; Alasasfeh, I.; Khader, Y.S.; Iblan, I. Knowledge, Awareness, and Compliance of Disease Surveillance and Notification Among Jordanian Physicians in Residency Programs. Inquiry 2019, 56, 0046958019856508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nsour, M.; Iblan, I.; Tarawneh, M.R. Jordan field epidemiology training program: Critical role in national and regional capacity building. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nsour, M.; Zindah, M.; Belbeisi, A.; Hadaddin, R.; Brown, D.W.; Walke, H. Prevalence of selected chronic, noncommunicable disease risk factors in Jordan: Results of the 2007 Jordan Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2012, 9, E25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, A.T.; Cookson, S.T.; Almashayek, I.; Yaacoub, H.; Qayyum, M.S.; Galev, A. An evaluation of a tuberculosis case-finding and treatment program among Syrian refugees - Jordan and Lebanon, 2013–2015. Confl. Health 2019, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikal, S.L.; Ge, L.; Mir, A.; Pace, J.; Abdulla, H.; Leong, K.F.; Benelkahla, M.; Olabi, B.; Medialdea-Carrera, R.; Padovese, V. Skin disease profile of Syrian refugees in Jordan: A field-mission assessment. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2020, 34, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessler, J.; Rodriguez-Barraquer, I.; Cummings, D.A.T.; Garske, T.; Van Kerkhove, M.; Mills, H.; Truelove, S.; Hakeem, R.; Albarrak, A.; Ferguson, N.M. Estimating Potential Incidence of MERS-CoV Associated with Hajj Pilgrims to Saudi Arabia, 2014. PLoS Curr. 2014, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljoudi, A.S. A University of the Hajj? Lancet 2013, 382, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Turki, Y.A. Mass Gathering Medicine New discipline to Deal with Epidemic and Infectious Diseases in the Hajj Among Muslim Pilgrimage: A Mini Review Article. J. Relig. Health 2016, 55, 1270–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field Epidemiology Training Program—Supervisor’s-General Message. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/depten/Epidemiology/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Field Epidemiology Training Program|College of Medicine. Available online: https://medicine.ksu.edu.sa/en/node/5783 (accessed on 27 February 2020).

- Razavi, S.; Saeednejad, M.; Salamati, P. Vaccination in Hajj: An overview of the recent findings. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 7, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Yusef, D.; Hayajneh, W.; Awad, S.; Momany, S.; Khassawneh, B.; Samrah, S.; Obeidat, B.; Raffee, L.; Al-Faouri, I.; Bani Issa, A.; et al. Large outbreak of coronavirus disease among wedding attendees, Jordan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2165–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).