Orchestrating Forest Policy in Italy: Mission Impossible?

Abstract

1. Introduction

Concepts of Forest Policy Participatory Processes

2. Materials and Methods

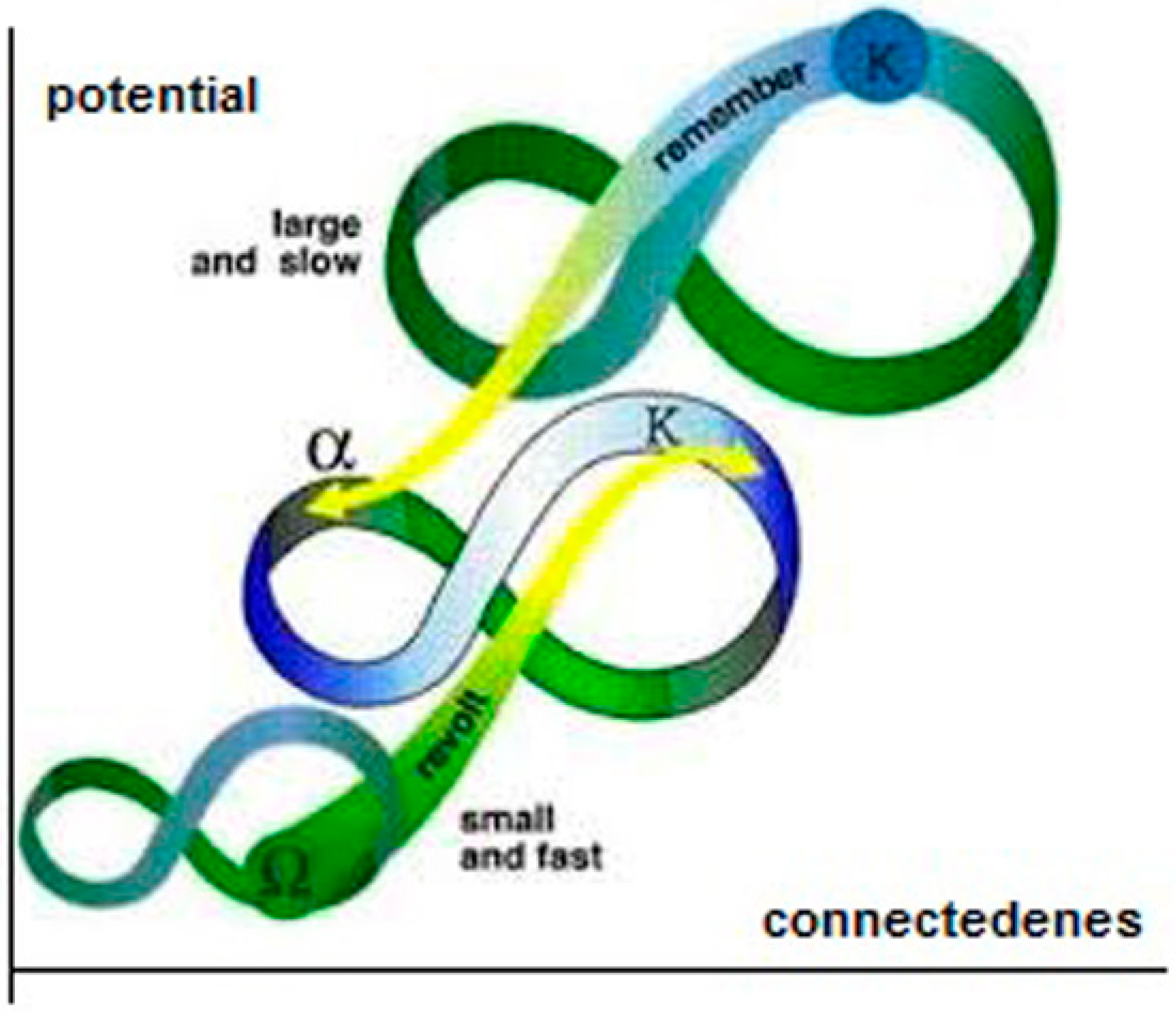

2.1. Our Framework: Combining Panarchy Theory and Forest Policy Participatory Processes

2.1.1. Phase 1: Growth (r)

2.1.2. Phase 2: Conservation (k)

2.1.3. Phase 3: Release (Ω)

2.1.4. Phase 4: Reorganization (α)

2.2. The Italian Context

2.3. Survey Methodology and Analytical Matrix

2.3.1. Semi-Structured Interviews

2.3.2. Case Studies Selection

2.3.3. Set of Criteria for Assessing the Level of Success of Participatory Processes

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Key-Examples of Forest-Related Participatory Processes in Italy

3.2. Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Forest-Related Participatory Processes in Italy

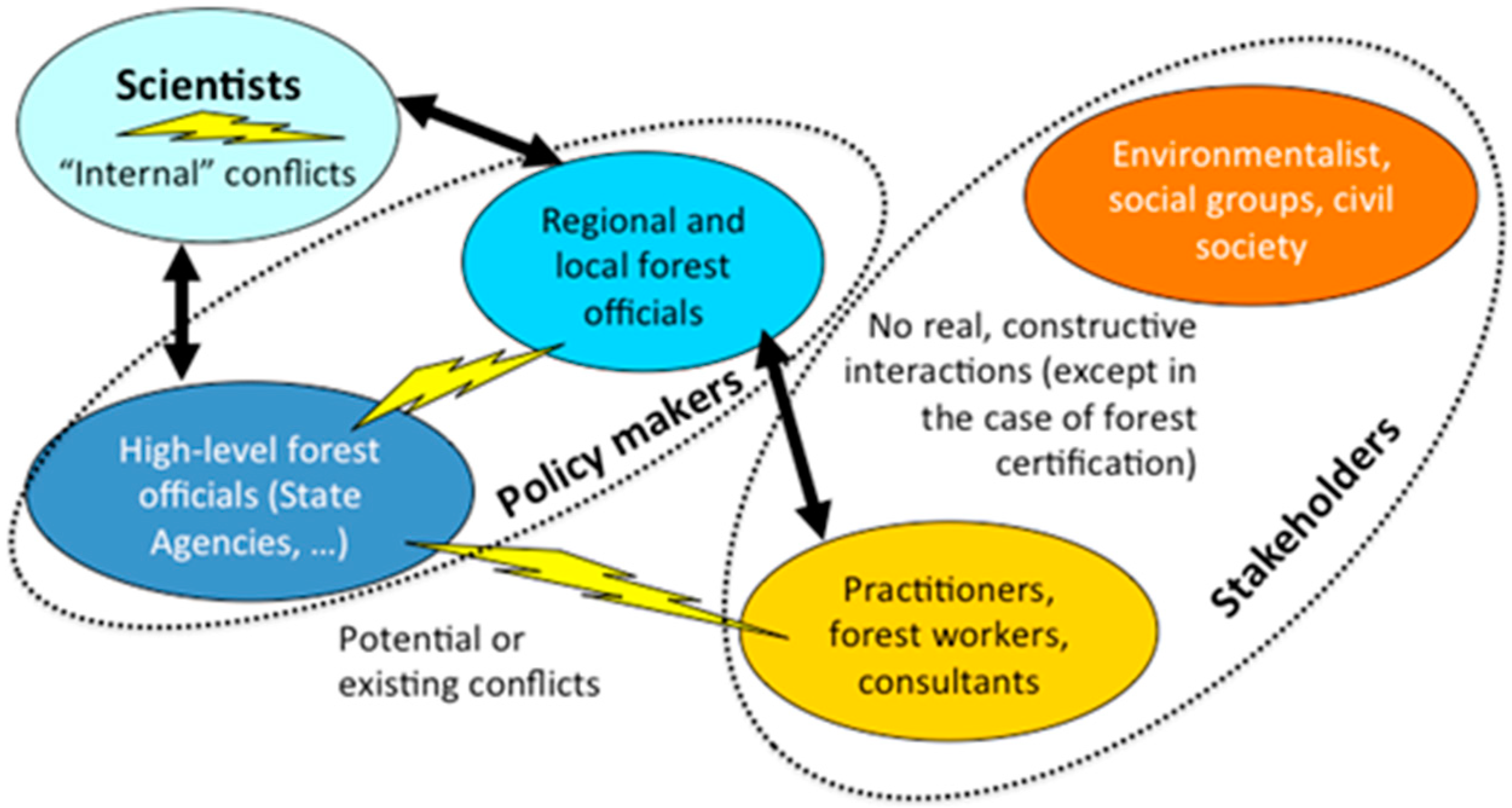

3.2.1. High Fragmentation of Forums

3.2.2. Lack of Clear Rules

3.2.3. Lack of Representativeness of Interests

3.3. Lessons Learned (or Not) for Orchestrating Forest Policy in Italy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lasserre, B.; Chirici, G.; Chiavetta, U.; Grafì, V.; Tognetti, R.; Drigo, R.; Di Martino, P.; Marchetti, M. Assessment of potential bioenergy from coppice forests through the integration of remote sensing and field surveys. Biomass Bioenerg. 2011, 35, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Giacovelli, G.; Pastorella, F. Stakeholders’ opinions and expectations for the forest-based sector: A regional case study in Italy. Int. For. Rev. 2017, 19, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secco, L.; Pettenella, D.; Gatto, P. Forestry governance and collective learning process in Italy: Likelihood or utopia? For. Policy Econ. 2011, 13, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantiani, M.G. Forest planning and public participation: A possible methodological approach. iForest 2012, 5, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Cantiani, M.G.; De Meo, I. Public participation in Forest Landscape Management Planning (FLMP) in Italy. J. Sustain. For. 2015, 34, 465–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinschmit, D.; Pülz, H.; Secco, L.; Sergent, A.; Wallin, I. Orchestration in political processes: Involvement of experts, citizens, and participatory professionals in forest policy making. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.R.; Angeler, D.G.; Garmestani, A.S.; Gunderson, L.H.; Holling, C.S. Panarchy: Theory and application. Ecosystems 2014, 17, 578–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, M. Design principles for science-stakeholder deliberation: A typology and tool box. In Proceedings of the COST Action ORCHESTRA Conference “Orchestrating Forest Policy MAKING: Involvement of Scientists and Stakeholders in Political Processes”, Bordeaux, France, 23–25 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- FAO-ECE-ILO. Public Participation in Forestry in Europe and North America; Report of the FAO/ECE/ILO Joint Committee Team of Specialists on Participation in Forestry, Working Paper 163; Sectorial Activities Department, International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. The World Bank and Participation; Operations Policy Department: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Forests. Report of the Ad Hoc intergovernmental panel on forests on its fourth session. In Proceedings of the Commission on Sustainable Development, Fifth session (UN DPCSD E/CN. 17/1997/12), New York, NY, USA, 7–25 April 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pülzl, H.; Rametsteiner, E. Grounding international modes of governance into National Forest Programmes. For. Policy Econ. 2002, 4, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvašová, Z.; Dobšinská, Z.; Šálka, J. Public participation in sustainable forestry: The case of forest planning in Slovakia. iForest 2014, 7, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. The Silent Revolution: Changing Values and Political Styles among Western Publics; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Vilkka, L. The Intrinsic Value of Nature; Value Inquiry Book Series; Rodopi: Helsinki, Finland, 1997; ISSN 0929-8436. [Google Scholar]

- Buttoud, G. How can policy take into consideration the “full value” of forests? Land Use Policy 2000, 17, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, C.; Lindkvist, A.; Öhman, K.; Nordström, E.M. Governing competing demands for forest resources in Sweden. Forests 2011, 2, 218–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, A. Multi-level governance. In Formulation and Implementation of National Forest Programmes, Theoretical Aspects; Glück, P., Oesten, G., Schanz, H., Volz, K.-R., Eds.; EFI Proceedings 30; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 1999; Volume 1, pp. 73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, S.E.; Walker, G.B. Working Through Environmental Conflict: The Collaborative Learning Approach; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Appelstrand, M. Participation and societal values: The challenge for lawmakers and policy practitioners. For. Policy Econ. 2002, 4, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, A.; Saarinen, N.; Saarikoski, H.; Leskinen, L.A.; Hujala, T.; Tikkanen, J. Stakeholder perspectives about proper participation for Regional Forest Programmes in Finland. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouplevatskaya-Buttoud, I.; Buttoud, G. Assessment of an iterative process: The double spiral of re-designing participation. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunckhorst, D.J. Institutions to sustain ecological and social systems. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2002, 3, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmestani, A.S.; Allen, C.R.; Mittelstaedt, J.D.; Stow, C.A.; Ward, W.A. Firm size diversity, functional richness and resilience. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2006, 11, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmestani, A.S.; Allen, C.R.; Cabezas, H. Panarchy, Adaptive management and governance: Policy options for building resilience. Neb. Law Rev. 2008, 87, 1036–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Garmestani, A.S.; Benson, M.H. A framework for resilience-based governance of social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppert-Winkel, C.; Winkel, G. Hidden in the woods? Meaning, determining, and practicing of ‘common welfare’ in the case of the German public forests. Eur. J. For. Res. 2001, 130, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faehnle, M.; Tyrväinen, L. A framework for evaluating and designing collaborative planning. Land Use Policy 2013, 34, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mårald, E.; Sandström, C.; Rist, L.; Rosvall, O.; Samuelsson, L.; Idenfors, A. Exploring the use of a dialogue process to tackle a complex and controversial issue in forest management. Scand. J. For. Res. 2015, 30, 749–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, S.; Montiel, C. The challenge of applying governance and sustainable development to wildland fire management in Southern Europe. J. For. Res. 2011, 22, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, C.; Lindner, T.; Winkel, G. Stakeholders’ perceptions of participation in forest policy: A case study from Baden-Württemberg. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secco, L.; Da Re, R.; Pettenella, D.M.; Gatto, P. Why and how to measure forest governance at local level: A set of indicators. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 49, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J. Glocal forest and REDD+ governance: Win-win or lose-lose? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogl, K.; Kvarda, E.; Nordbeck, R.; Pregernig, M. (Eds.) Effectiveness and legitimacy of environmental governance—Synopsis of key insights. In Environmental Governance: The Challenge of Legitimacy and Effectiveness; Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, UK, 2012; pp. 280–304. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S.; Kant, S.; Amburgey, T.L. Public agencies and collaborative management approaches. Examining resistance among administrative professionals. Adm. Soc. 2007, 39, 569–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rametsteiner, E. The role of governments in forest certification—A normative analysis based on new institutional economic theories. For. Policy Econ. 2002, 4, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.C.; Ostrom, E.; Ahn, T.K. The concept of scale and the human dimensions of global change: A survey. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Meo, I.; Ferretti, F.; Hujala, T.; Kangas, A. The usefulness of Decision Support Systems in participatory forest planning: A comparison between Finland and Italy. For. Syst. 2013, 22, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Applied Social Research Methods Series; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Secco, L.; Pettenella, D. Participatory processes in forest management: The Italian experience in defining and implementing forest certification schemes. Swiss For. J. 2006, 157, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, F.; Savelli, S. Forestry programmes and the contribution of the forestry research community to the Italy experience. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, L.; Romano, R. Politiche Forestali e Sviluppo Rurale: Situazione, Prospettive e Buone Prassi, Quaderno n. 1; Osservatorio Foreste INEA: Roma, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- De Meo, I.; Ferretti, F.; Frattegiani, M.; Lora, C.; Paletto, A. Public participation GIS to support a bottom-up approach in forest landscape planning. iForest 2013, 6, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaro, L.; Romano, R.; Zumpano, C. Foreste e Politiche di Sviluppo Rurale: Stato Dell’arte, Opportunità Mancate e Prospettive Strategiche; INEA: Roma, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, R.; Marandola, M. Le Politiche Forestali in Italia: Tema di Nicchia Oppure Reale Occasione di Sviluppo Integrato Per Il Paese? Criticità, Opportunità E Strumenti Alle Soglie Della Programmazione 2014–2020. In Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Silviculture, Florence, Italy, 26–29 November 2014; pp. 775–779. [Google Scholar]

- De Meo, I.; Ferretti, F.; Paletto, A.; Cantiani, M.G. An approach to public involvement in forest landscape planning in Italy: A case study and its evaluation. Ann. Silvic. Res. 2017, 41, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock, K.L.; Kelly, G.J.; Horsey, B.L. Developing and applying a framework to evaluate participatory research for sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, S.; Nordstrom, E.M.; Buchecker, M.; Marques, A.; Saarikoski, H.; Kangas, A. Decision support systems in forest management: Requirements from a participatory planning perspective. Eur. J. For. Res. 2012, 131, 1367–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Graves, A.; Dandy, N.; Posthumus, H.; Hubacek, K.; Morris, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Stringer, L.C. Who’s in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 1933–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilli, G.; Garegnani, G.; Poljanec, A.; Ficko, A.; Vettorato, D.; De Meo, I.; Paletto, A. Stakeholder analysis in the biomass energy development based on the experts’ opinions: The example of Triglav National Park in Slovenia. Folia For. Pol. Ser. A 2015, 57, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M. Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: A framework, principles and performance outcomes. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saarikoski, H.; Tikkanen, J.; Leskinen, L.A. Public participation in practice—Assessing public participation in the preparation of regional forest programs in Northern Finland. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 12, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuler, S.; Webler, T. Voices from the forest: What participants expect of a public participation process. Soc. Nat. Resour. 1999, 12, 437–453. [Google Scholar]

- Brinkerhoff, J.M. Assessing and improving partnership relationships and outcomes: A proposed framework. Eval. Prog. Plan. 2002, 25, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanagas, N.D. Network analysis functionality in environmental policy: Combining abstract software engineering with field empiricism. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Control 2011, 6, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, J. Implementing participatory decision making in forest planning. Environ. Manag. 2007, 29, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asthana, S.; Richardson, S.; Halliday, J. Partnership working in public policy provision: A framework for evaluation. Soc. Policy Adm. 2002, 36, 780–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstad, B.H. ‘What’s in it for me?’—Contrasting environmental organisations and forest owner participation as policies evolve. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 89, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Forest cover | From the National Forestry Inventory data, the area covered by forests is 10.9 M ha (more than 30% of the total land) and has increased by 0.6 M ha since 2005. 95% of forest is distributed in the mountains and hilly areas, mainly the Alps and Apennines. The majority of forest area is under coppice regime (41.8%), especially in Central and Southern Italy, while high forests of coniferous and broadleaves (36.1%) are predominant in the North. The percentage of “not defined” forest types is significant (20.8%). |

| Property regime | More than 63.5% of forest area is private, 32.4% is public and 4.1% is not qualified. There are positive forms of management association in some areas, but at national scale forest firms are managed by forest-owners. Results of the Census 2011 have counted 328,358 forest firms and the forest area included in the firms is 2.9 M ha, with an average size of 8.9 ha. A few bigger firms (>100 ha), 3.7%, manage the largest amount of forest (64.7%) with an average firm of more than 150 ha; while the largest number of firms (<100 ha), 96.4%, manage only 35.3% of forest area, with an average of less than 3 ha/firm. The most relevant figure, however, is the amount of forest not included in active forest firms i.e., 3 M ha. |

| Forest management | It is developed according to the rules dictated by the regional forest code and regional forest laws. Frequently firms in the North manage forest according to the Forest Plan forecasts, and thanks to the support of EU funds; the firms adopting a forest plan are increasing even in the other regions and especially for public property. |

| Production | In the period 2010–2014 average timber production was in the range 7–6 M m3/year. This is mainly for energy use (63.7%), while 31.9% is classified as roundwood. Other (non-timber) forest products (NTFPs), chestnuts, mushrooms, strawberries and plants for food are gathered. A large amount is for self-consumption, but companies that use NTFPs for economic activities are increasing. |

| Forestry economic performance | The added value of the forest sector has been estimated as €1.2–1.5 million in the last 5-years, with a contribution to the total value of national economic activity of ca. 0.05% while its contribution to GDP at national level is 0.09%. |

| Political Level | Period | Participative Forums or Decision-Making Processes | Description/Policy Field/Goals | Responsible for Launching and/or Managing the Forum/Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | 1996–ongoing | State-Regions Conference-Forest Division | To coordinate state and regions debate on various forest policy issues: Law contents, emergency plans for pests and diseases management, market strategies, forest management and policy reforms guidelines. | Italian government |

| 1996–2000 | National Working Group on Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) standards for Northern Italy (Milano Forum) | To develop a commonly agreed set of SFM standards to guide forest management and create a basis for forest certification implementation in Northern Italy, with no references to any specific forest certification scheme. | Department of Land, Environment, Agriculture and Forestry (TESAF)-University of Padova, Department DEIAFA-University of Turin | |

| 2001–ongoing | Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)-Italy working group on SFM standards for the Italian Alpine regions | To develop, approve and periodically update with stakeholders participation a set of national standards for SFM consistent with the international set of FSC Principles and Criteria. | FSC-Italy (National Secretariat) | |

| Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC)-Italy working group on SFM national standards | To develop and approve with stakeholders participation a set of standards for SFM consistent with the Pan-European set of Criteria and Indicators specific to the Italian context for PEFC forest certification processes. | PEFC-Italy (National Secretariat) | ||

| 2002–ongoing | Scientific Committee of Services Consortium wood-cork (CONLEGNO) | To promote the quality of companies and their products in timber and related sectors. To promote the provision of services related to stages of production of the member’s undertakings. | CONLEGNO Monitoring Organization (National Committee) | |

| 2003–2005 | National Working Group on SFM standards for Apennine and Mediterranean forests (SAM) | To develop a commonly agreed set of SFM standards to guide forest management and create a basis for forest certification in Central and Southern Italy, with no references to any specific forest certification scheme. | Italian Academy of Forest Sciences | |

| 2007–2009 | Framework Program for the Forest Sector (PQSF) | To identify general strategies and policy guidelines for the forest sector. No funds or other resources have been allocated for implementation. | Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry Policies | |

| 2012–ongoing | Table on Forest-Wood chain | To define new tools, strategies and networks to increase the supply of domestic timber. The table is structured into working groups, including key forest sector stakeholders. Other sectors and interests (e.g., environmentalists) not involved. | Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry Policies. The National Rural Network manages the process | |

| 2007–ongoing | Carbon Monitoring Nucleon | To provide updated information on forest carbon sequestration/stocks, and develop common guidelines for monitoring, forest carbon investments, etc. | National Institute of Agricultural Economics (INEA) (now transformed into CREA) | |

| Regional | 2005–2006 | Rural Development Plans (RDP) 2007–2013 | The RDPs at regional level were developed by adopting a participatory approach, as formally required by the EU rules. | Regional Administrations (e.g., Veneto, Piedmont) |

| 2012–ongoing | Sub-sectoral forum on poplar plantations | To develop strategies for improving the production of timber from poplar plantations in Northern Italian regions. In this sense, it is an interregional initiative. | Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry Policies through Consulta Nazionale Pioppo, jointly with the National Research Council in Agriculture and Poplar Plantation Owners Association | |

| 2014–ongoing | Regulations for implementing the new regional forest law in Piedmont (approved in 2009) | To define specific rules and regulations for a recently approved forest reform in Piedmont. | Regional Administration (Piedmont) | |

| Local | 2010 (2 months) | Regulation on harvesting allocation in the Monte Rosa Foreste Association | To decide how to allocate harvesting on public stands to private logging companies on the basis of public rules. | Monte Rosa Foreste Association |

| 2009–2012 | Partnership for the process of building the Model Forest “Montagna Fiorentina” | To improve the integration and sustainability of forest and land management, increasing the cohesion and awareness of the network of all the social-economic components that directly or indirectly belong to that territory. | Tuscany Region in coordination with Mediterranean Model Forest Network secretariat. Union of Municipalities Valdisieve Valdarno (Florence) is the manager |

| Criteria | National Level | Local Level | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forum 1 | Forum 2 | Forum 3 | Forum 4 | ||

| 1. Representativeness | Stakeholders | ||||

| State authorities (i.e., Ministries) | X | X | X | ||

| Regional authorities | X | X | X | X | |

| Local authorities | X | X | X | X | |

| Scientists/experts | X | X | X | X | |

| Tourist associations | X | X | |||

| Forest owner associations | X | X | X | X | |

| Private timber enterprises | X | X | X | X | |

| Farmers associations | X | X | X | X | |

| Hunting associations | X | X | |||

| Citizens | |||||

| 2. Inclusiveness | Levels | ||||

| Information | |||||

| Consultation | X | X | |||

| Advocacy | |||||

| Decision-making | - | X | |||

| 3. Transparency | Levels | ||||

| Very high | X | ||||

| High | X | ||||

| No opinion | |||||

| Low | X | X | |||

| Very low | |||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Secco, L.; Paletto, A.; Romano, R.; Masiero, M.; Pettenella, D.; Carbone, F.; De Meo, I. Orchestrating Forest Policy in Italy: Mission Impossible? Forests 2018, 9, 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9080468

Secco L, Paletto A, Romano R, Masiero M, Pettenella D, Carbone F, De Meo I. Orchestrating Forest Policy in Italy: Mission Impossible? Forests. 2018; 9(8):468. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9080468

Chicago/Turabian StyleSecco, Laura, Alessandro Paletto, Raoul Romano, Mauro Masiero, Davide Pettenella, Francesco Carbone, and Isabella De Meo. 2018. "Orchestrating Forest Policy in Italy: Mission Impossible?" Forests 9, no. 8: 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9080468

APA StyleSecco, L., Paletto, A., Romano, R., Masiero, M., Pettenella, D., Carbone, F., & De Meo, I. (2018). Orchestrating Forest Policy in Italy: Mission Impossible? Forests, 9(8), 468. https://doi.org/10.3390/f9080468