Revitalizing REDD+ Policy Processes in Vietnam: The Roles of State and Non-State Actors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Who are the actors involved in REDD+ policy and what is their level of influence in the NRAP processes?

- What are the factors shaping non-state actors’ influence in REDD+?

- What mechanisms and strategies might lead to better outcomes for REDD+ policy?

1.1. Governance and Policy-Making

1.2. Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) in Vietnam

2. Research Methods

3. Results

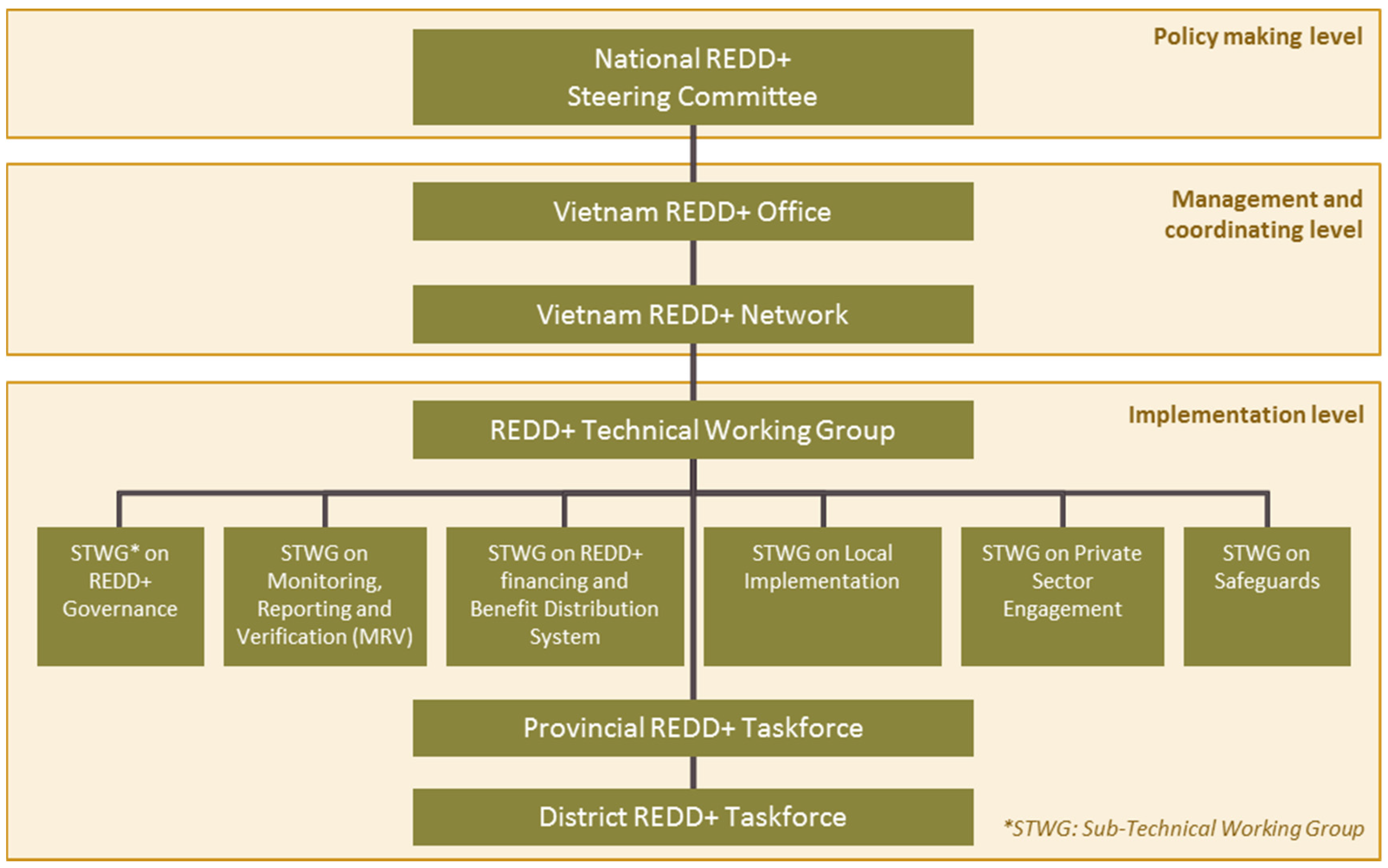

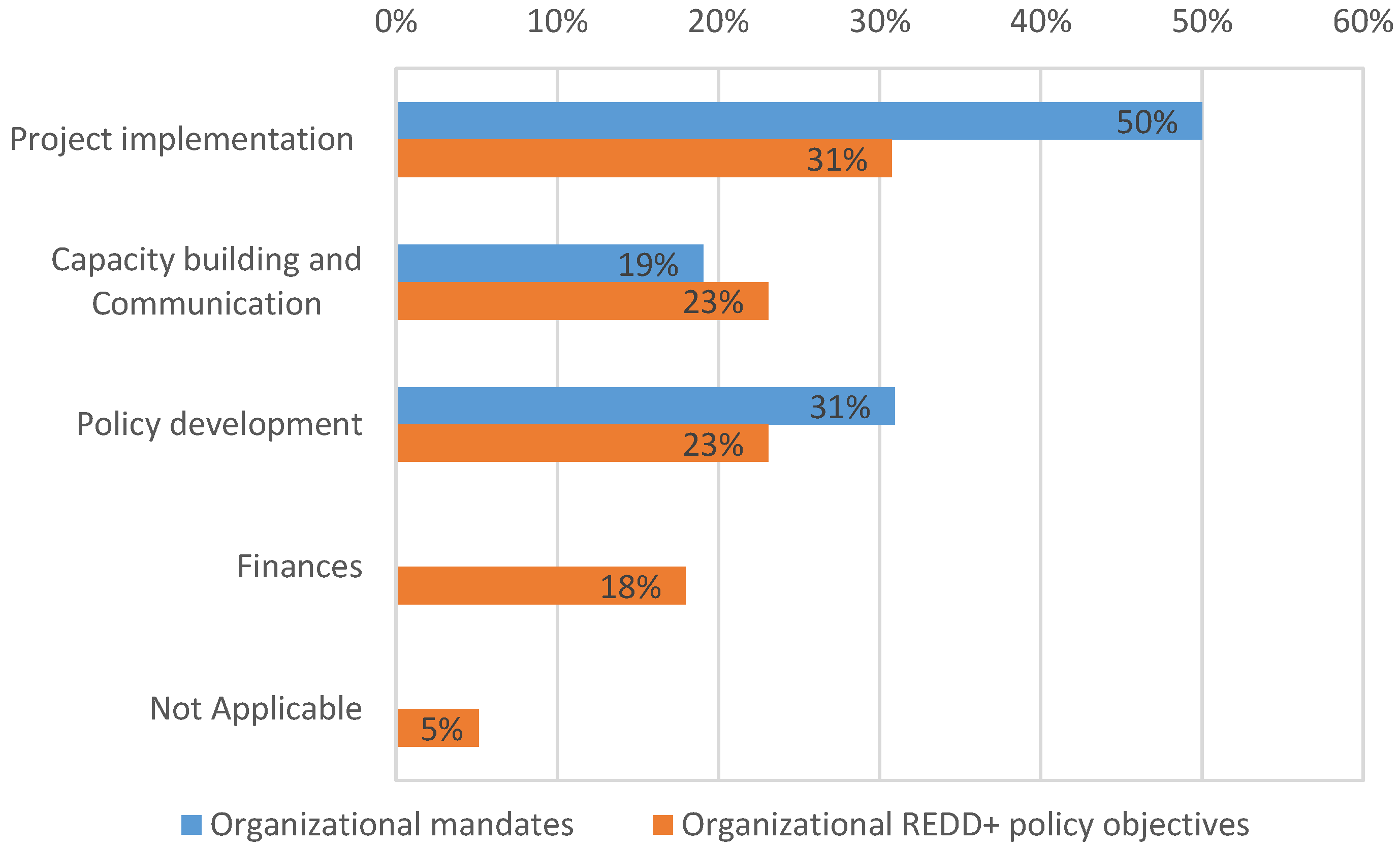

3.1. Who Are the Actors Involved in REDD+ Policy Processes?

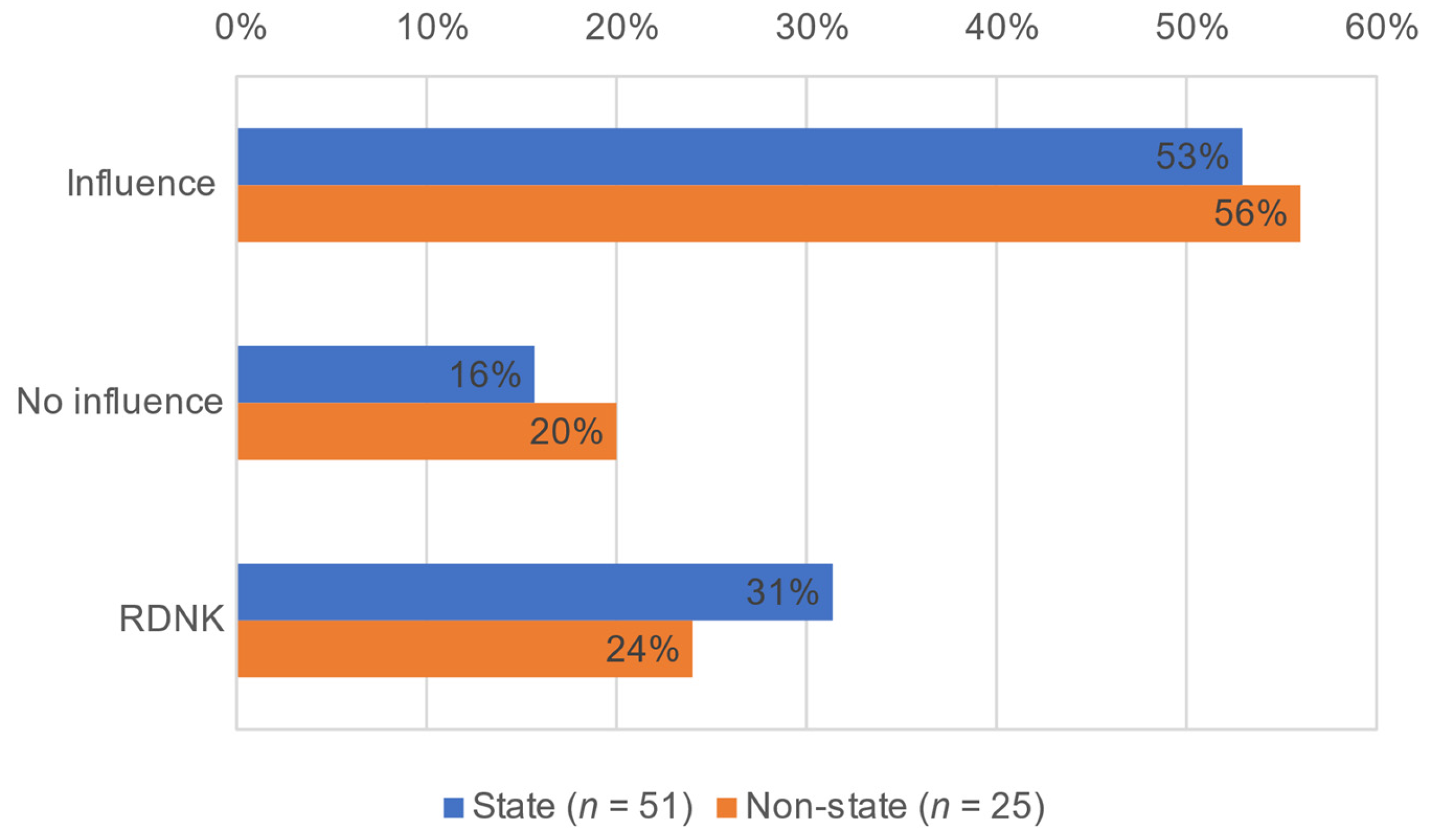

3.2. How Do Actors View Their Influence in the NRAP Processes?

4. Analysis and Discussion

4.1. What Are Factors Shaping Non-State Actors’ Influence in REDD+ Policy Processes?

4.2. Mechanisms and Strategies to Enhance REDD+ Policy Processes

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Definition |

| CBO | Community-Based Organization |

| CIFOR | Center for International Forestry Research |

| CSI | Civil Society Index |

| CSO | Civil Society Organization |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FCPF | Forest Carbon Partnership Facility of the World Bank |

| GCS | Global Comparative Study |

| GOV | Government |

| INGO | International Non-Governmental Organization |

| MARD | Vietnam Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development |

| MRV | Measurement, Reporting and Verification |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| NRAP | National REDD+ Action Program |

| RDKN | Respondent Does Not Know |

| REDD | Reducing Emissions From Deforestation and Forest Degradation |

| STWG | Sub-Technical Working Group |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNEP | United Nations Environment Programme |

| USA | United States of America |

| USD | US Dollar |

| VIC | Victoria |

| VNGO | Vietnam Non-Governmental Organization |

References

- Angelsen, A.; Brockhaus, M.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Verchot, L.V. Analysing REDD+: Challenges and Choices; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2012; p. 426. [Google Scholar]

- Simonet, G.; Karsenty, A.; de Perthuis, C.; Newton, P.; Schaap, B.; Seyller, C. REDD+ Projects in 2014: An Overview Based on a New Database and Typology. Available online: http://www.chaireeconomieduclimat.org/en/publications-en/information-debates/id-32-redd-projects-in-2014-an-overview-based-on-a-new-database-and-typology/ (accessed on 15 January 2017).

- Brockhaus, M.; Angelsen, A. Seeing REDD+ through 4is: A political economy framework. In Analysing REDD+: Challenges and Choices; Center for International Forestry Research: Bogor, Indonesia, 2012; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sills, E.O.; Atmadja, S.; de Sassi, C.; Duchelle, A.E.; Kweka, D.; Resosudarmo, I.A.P.; Sunderlin, W.D. REDD+ on the Ground: A Case Book of Subnational Initiatives across the Globe; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, R.; Hargita, Y.; Günter, S. Insights from the ground level? A content analysis review of multi-national REDD+ studies since 2010. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 66, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, R.J. The paris climate agreement and forests: Will the cop21 agreement encourage growth in investment in sustainably-managed forests? Asia Pac. Policy Soc. 2016. Available online: www.policyforum.net/the-paris-climate-agreement-and-forests/ (accessed on 15 January 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A polycentric approach for coping with climate change. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5095; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderlin, W.; Sills, E.; Duchelle, A.; Ekaputri, A.; Kweka, D.; Toniolo, M.; Ball, S.; Doggart, N.; Pratama, C.; Padilla, J. REDD+ at a critical juncture: Assessing the limits of polycentric governance for achieving climate change mitigation. Int. For. Rev. 2015, 17, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen-Kurki, K.; Brockhaus, M.; Bushley, B.R.; Babon, A.; Gebara, M.F.; Kengoum Djiegni, F.; Pham, T.T.; Rantala, S.; Moeliono, M.; Dwisatrio, B.; et al. Coordination and Cross-Sectoral Integration in REDD+: Experiences from Seven Countries. Clim. Dev. 2015, 8, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanowski, P.J.; McDermott, C.L.; Cashore, B.W. Implementing REDD+: Lessons from analysis of forest governance. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, D. Logjam: Deforestation and the Crisis of Global Governance; Earthscan: London, UK; Sterling, VA, USA, 2006; p. 302. [Google Scholar]

- Minang, P.A.; Van Noordwijk, M.; Duguma, L.A.; Alemagi, D.; Do, T.H.; Bernard, F.; Agung, P.; Robiglio, V.; Catacutan, D.; Suyanto, S. REDD+ readiness progress across countries: Time for reconsideration. Clim. Policy 2014, 14, 685–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cường, L.V.; Quang, Đ.V.; Đơ, T.T. Báo Cáo Dòng Tài Chính REDD+ Tại Việt Nam Giai Đoạn 2009–2014; REDD+ Vietnam and Forest Trend: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN-REDD. Operationalizing REDD+ in Viet Nam through Provincial REDD+ Action Plans (PRAP) REDD+ and the Rationale for Sub-National Planning; UN-REDD Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- MARD. Participatory Self-Assessment of the REDD+ Readiness Package in Vietnam; MARD: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UN-REDD. Site-Based REDD+ Implementation Plan (Sirap) in Viet Nam; UN-REDD Vietnam Phase II Program: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- London, J.D. Politics in contemporary vietnam. In Politics in Contemporary Vietnam; Palgrave Macmillan: Hampshire, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Brockhaus, M.; Di Gregorio, M.; Mardiah, S. Governing the design of national Redd+: An analysis of the power of agency. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 49, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisaki, T.; Hyakumura, K.; Scheyvens, H.; Cadman, T. Does REDD+ ensure sectoral coordination and stakeholder participation? A comparative analysis of Redd+ national governance structures in countries of asia-pacific region. Forests 2016, 7, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaels, R. The mirage of non-state governance. Utah Law Rev. 2010, 2010, 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison/Michel Foucault; Translated from the French by Alan Sheridan; Vintage Books: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Knieling, J.; Leal Filho, W. Climate Change Governance; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lemos, M.C.; Agrawal, A. Environmental governance. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2006, 31, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. Environmental Policy; Taylor and Francis: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cashore, B.; Vertinsky, I. Policy networks and firm behaviours: Governance systems and firm reponses to external demands for sustainable forest management. Policy Sci. 2000, 33, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, B. Collaborating: Finding Common Ground for Multiparty Problems; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, N. Wicked problems and network approaches to resolution. Int. Public Manag. Rev. 2000, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.R.A.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C. What is social learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colebatch, H.K. Beyond the Policy Cycle: The Policy Process in Australia; Colebatch, H.K., Ed.; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A. Grass Roots and Green Tape: Principles and Practices of Environmental Stewardship; Federation Press: Leichhardt, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, H.; Buchy, M.; Proctor, W. Laying down the ladder: A typology of public participation in australian natural resource management. Aust. J. Environ. Manag. 2002, 9, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K.; Ison, R. Jumping off arnstein’s ladder: Social learning as a new policy paradigm for climate change adaptation. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 358–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayers, J.; Bass, S. Policy That Works for Forests and People/Authors, James Mayers and Stephen Bass; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jochim, A.E.; May, P.J. Beyond subsystems: Policy regimes and governance. Policy Stud. J. 2010, 38, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weible, C.M. Expert-based information and policy subsystems: A review and synthesis. Policy Stud. J. 2008, 36, 615–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termeer, C.; Dewulf, A.; Breeman, G. Governance of wicked climate adaptation problems. In Climate Change Governance; Springer: Berlin, Germany; New York, USA, 2013; pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, P. Climate for Change: Non-State Actors and the Global Politics of the Greenhouse; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Keen, S. Non-governmental organitions in policy. In Beyond the Policy Cycle: The Policy Process in Australia; Colebatch, H.K., Ed.; Allen & Unwin: Crows Nest, NSW Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dombrowski, K. Filling the gap? An analysis of non-governmental organizations responses to participation and representation deficits in global climate governance. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2010, 10, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A. Moving ahead with REDD: Issues, Options and Implications; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2008; p. 156. [Google Scholar]

- Cadman, T.; Maraseni, T.; Breakey, H.; López-Casero, F.; Ma, H.O. Governance values in the climate change regime: Stakeholder perceptions of Redd+ legitimacy at the national level. Forests 2016, 7, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucius, C. Vietnam’s Political Process: How Education Shapes Political Decision Making; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Angelsen, A.; Brockhaus, M.; Kanninen, M.; Sills, E.; Sunderlin, W.D.; Wertz-Kanounnikoff, S. Realising Redd+: National Strategy and Policy Options; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2009; p. 361. [Google Scholar]

- Vijge, M.J.; Brockhaus, M.; Di Gregorio, M.; Muharrom, E. Framing national Redd+ benefits, monitoring, governance and finance: A comparative analysis of seven countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 39, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Future Role of Civil Society; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- NORAD. Real-Time Evaluation of Norway’s International Climate and Forest Initiative; Lessons Learned from Support to Civil Society Organisations; NORAD: Oslo, Norway, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, D. Ngos and Environmental Policies: Asia and Africa; David, P., Ed.; FRANK Cass: Portland, OR, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Norlund, I. Civil society in Vietnam. Social organisations and approaches to new concepts. Asien 2007, 105, 68–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fforde, A. Civil society, the state, and the business sector–protagonists of democratization processes? Insights from vietnam. In Towards Good Society: Civil Society Actors, the State and the Business Class in Southeast Asia–Facilitators of or Impediments to a Strong, Democratic, and Fair Society; Agit-Druck: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 173–192. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, J. Local Non-Government Organizations in Vietnam: Development, Civil Society and State-Society Relations; University of Washington: Seatle, WA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- William, T.; Nguyễn, T.H.; Phạm, Q.T.; Tuyết, H.T.N. Civil Society in Vietnam: A Comparative Study of Civil Society Organizations in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City; The Asia Foundation: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Thaveeporn, V. Authoritarianism reconfigured: Evolving accountability relations within Vietnam’s one-party rule. In Politics in Contemporary Vietnam: Party, State, and Authority Relation; London, J.D., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Houndmills, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, T.H. The development of civil society and dynamics of governance in Vietnam’s one party rule. Glob. Chang.Peace Secur. 2013, 25, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells-Dang, A. The political influence of civil society in vietnam. In Politics in Contemporary Vietnam: Party, State, and Authority Relations; London, J.D., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: Houndmills, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Jung, J. Politics in contemporary Vietnam: Party, state and authority relations. Contemp. Southeast Asia 2014, 36, 473–476. [Google Scholar]

- Norlund, I.; SNV; UNDP Viet Nam; Viet Nam, L.H.H.K.H. Filling the Gap: The Emerging Civil Society in Viet Nam; Viet Nam Union of Science and Technology Associations: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; p. 766. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Vietnam. National REDD+ Action Program; MARD: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012.

- UN-REDD. Lessons Learned Viet Nam Un-REDD Programme, Phase 1; UN-REDD: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, T.B.; Bumpus, A. Stakeholder Analysis & Stakeholder Engagement for the Implementation of National REDD Action Plan in Viet Nam; UN-REDD: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vietnam, R. Institutional Arrangement for REDD+ in Viet Nam. Available online: http://www.vietnam-Redd.org/Web/Default.aspx?tab=introdetail&zoneid=106&itemid=428&lang=en-US (accessed on 1 September 2016).

- Duong, M.N. Grassroots Democracy in Vietnamese Communes; The Centre for Democratic Institutions, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University: Canberra, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T.T.; Moeliono, M.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, H.T.; Vu, T.H. The Context of REDD+ in Vietnam: Drivers, Agents and Institutions; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Howell, J.; Pearce, J. Civil Society and Development: A Critical Exploration; L. Rienner Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Di Gregorio, M.; Brockhaus, M.; Cronin, T.; Muharrom, E.; Mardiah, S.; Santoso, L. Deadlock or transformational change? Exploring public discourse on REDD+ across seven countries. Glob. Environ. Politics 2015, 15, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells-Dang, A.; Wells-Dang, G. Civil society in asean: A healthy development? Lancet 2011, 377, 792–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P.M.; Hien, H.M.; Lien, T.V. Responding to el nino and la nina: Averting tropical cyclone impacts. In Living with Environmental Change: Social Vulnerability, Adaptation and Resilience in Vietnam; Adger, N., Kelly, P.M., Nguyen, H.N., Ebrary, I.N.C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2001; p. 314. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R. Unlocking organizational routines that prevent learning. Syst. Think. 1993, 4, 2–4. [Google Scholar]

- Beutz, M. Functional democracy: Responding to failures of accountability. Harv. Int. Law J. 2003, 44, 387. [Google Scholar]

- CECODES; VFF-CRT; UNDP. The Viet Nam Governance and Public Administration Performance Index (PAPI) 2015: Measuring Citizens’ Experiences; Centre for Community Support and Development Studies (CECODES), Centre for Research and Training of the Viet Nam Fatherland Front (VFF-CRT), and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): Hanoi, Vietnam, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Jung, J. Vietnam’s New Environmental Politics: A Fish out of Water? Available online: http://thediplomat.com/2016/05/vietnams-new-environmental-politics-a-fish-out-of-water/ (accessed on 3 October 2016).

- Haas, P.M. Introduction: Epistemic communities and international policy coordination. Int. Org. 1992, 46, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Expressed Themes | State Actors (n = 56) (%) | Non- State Actors (n = 25) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative views | Limited participation and top down approach Ineffective mechanisms Lack of coordination and inadequate information sharing Absence of government (GOV) leadership | 32 | 33 |

| Positive views | Awareness raising and interesting debates via numerous workshops Open to various stakeholders REDD+ Network as an effective mechanism for consultation | 30 | 30 |

| Respondents do not know | Not aware of the process | 22 | 17 |

| Other comments | Neutrality is necessary A better mechanism is required Roles of REDD+ network, civil society organisations (CSOs,) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) need to be strengthened and empowered Clear goals, specific agendas, and creative approach. | 16 | 20 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huynh, T.B.; Keenan, R.J. Revitalizing REDD+ Policy Processes in Vietnam: The Roles of State and Non-State Actors. Forests 2017, 8, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8030053

Huynh TB, Keenan RJ. Revitalizing REDD+ Policy Processes in Vietnam: The Roles of State and Non-State Actors. Forests. 2017; 8(3):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8030053

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuynh, Thu Ba, and Rodney J. Keenan. 2017. "Revitalizing REDD+ Policy Processes in Vietnam: The Roles of State and Non-State Actors" Forests 8, no. 3: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8030053

APA StyleHuynh, T. B., & Keenan, R. J. (2017). Revitalizing REDD+ Policy Processes in Vietnam: The Roles of State and Non-State Actors. Forests, 8(3), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/f8030053