Predawn Disequilibrium Between Soil and Plant Water Potentials in Seedlings of Two Mediterranean Oak Species (Quercus ilex and Quercus suber)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material, Experimental Site and Setup

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Plant Water Status: Plant Water Potential and Hydration

2.2.2. Leaf Gas Exchange

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

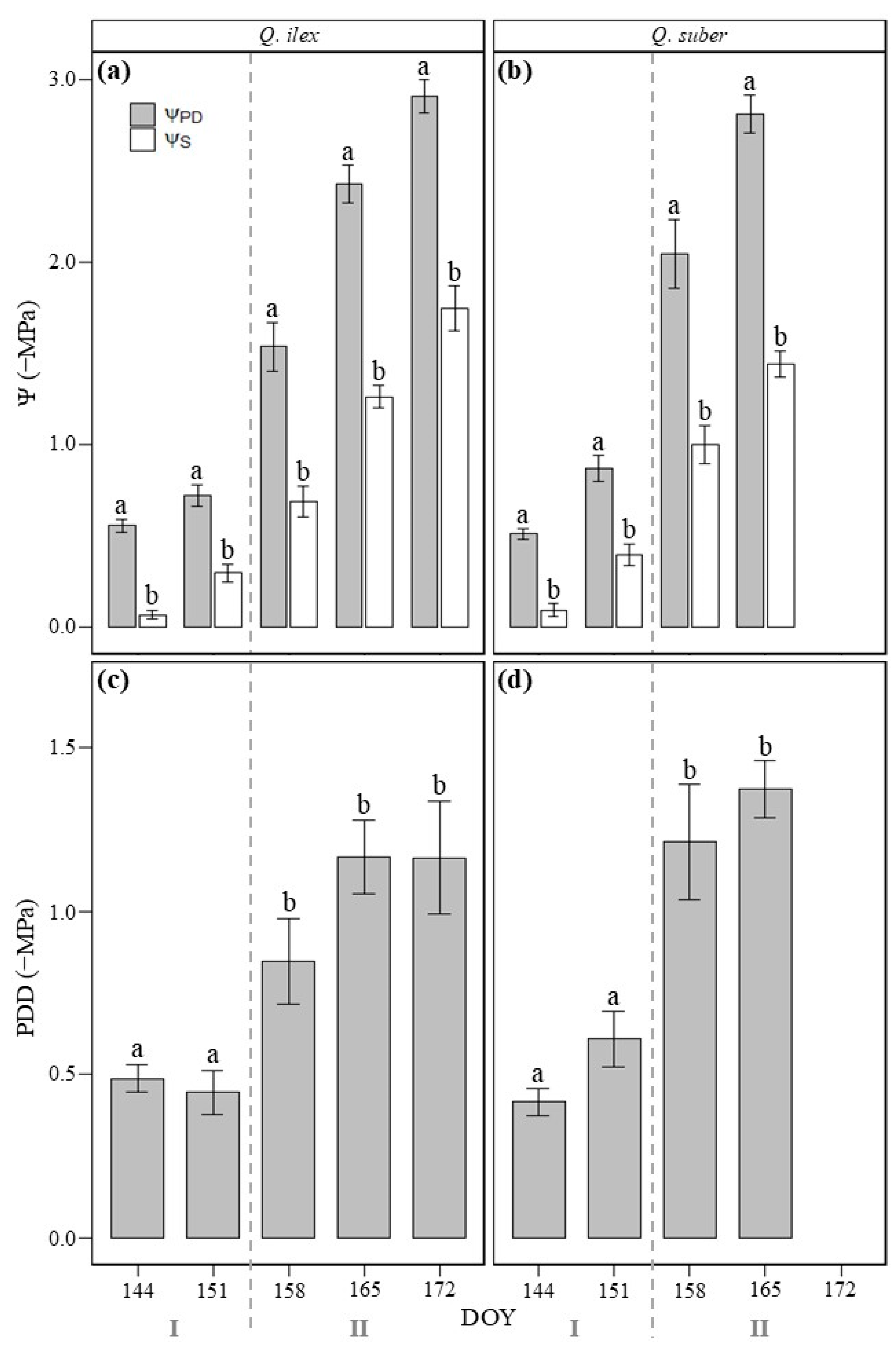

3.1. Relationship Between Soil (ΨS) and Leaf Water Potential Before Dawn (ΨPD)

3.2. Soil–Plant Water Potential Disequilibrium Before Dawn (PDD)

3.3. Stomatal Conductance and Drought Tolerance

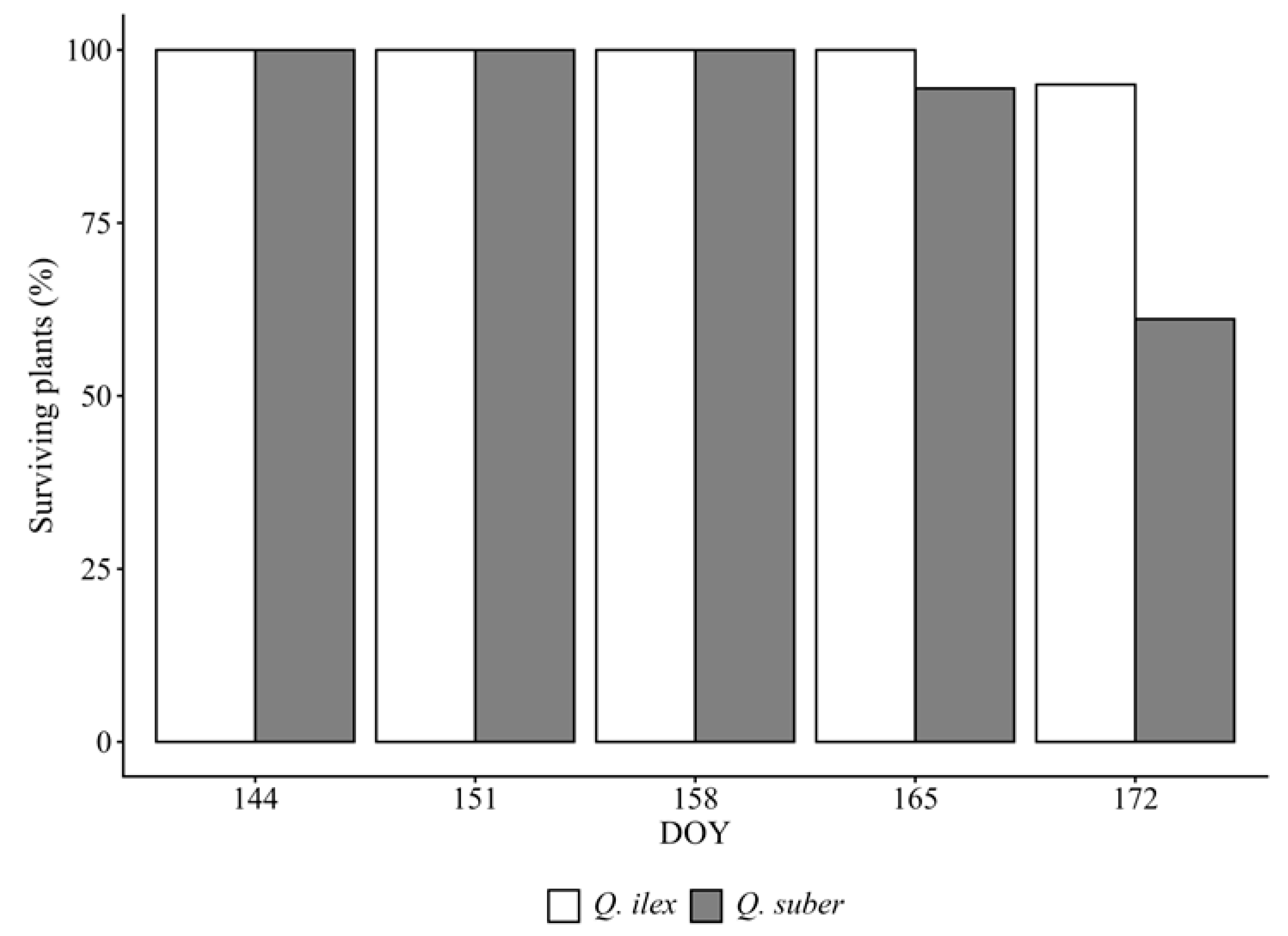

3.4. Differential Mortality Under Drought Stress

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDD | Predawn Disequilibrium |

| LMM | Linear Mixed-Effects Model |

| GLMM | Generalised Linear Mixed-Effects Model |

| LMA | Leaf Mass Area |

| SPAC | Soil–Plant-Atmosphere Continuum |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

| VPD | Vapour Pressure Deficit |

| DOY | Day Of the Year |

| BPD | Before Predawn |

References

- Deitch, M.J.; Sapundjieff, M.J.; Feirer, S.T. Characterizing Precipitation Variability and Trends in the World’s Mediterranean-Climate Areas. Water 2017, 9, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mediavilla, S.; Escudero, A. Stomatal Responses to Drought at a Mediterranean Site: Study of Co-Occurring Woody Species Differing in Leaf Longevity. Tree Physiol. 2003, 23, 987–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Plant-Soil Interactions in Mediterranean Forest and Shrublands: Impacts of Climatic Change. Plant Soil. 2013, 365, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Vilagrosa, A.; Alonso-Forn, D.; Ferrio, J.P.; Sancho-Knapik, D.; Gil-Pelegrín, E. Living in Drylands: Functional Adaptations of Trees and Shrubs to Cope with High Temperatures and Water Scarcity. Forests 2020, 11, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, F.M.; Pugnaire, F.I. Rooting Depth and Soil Moisture Control Mediterranean Woody Seedling Survival during Drought. Funct. Ecol. 2007, 21, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Santana, V.; David, T.S.; Martínez-Fernández, J. Environmental and Plant-Based Controls of Water Use in a Mediterranean Oak Stand. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 3707–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcuera, L.; Camarero, J.J.; Gil-Pelegrín, E. Functional Groups in Quercus Species Derived from the Analysis of Pressure-Volume Curves. Trees—Struct. Funct. 2002, 16, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limousin, J.M.; Misson, L.; Lavoir, A.V.; Martin, N.K.; Rambal, S. Do Photosynthetic Limitations of Evergreen Quercus ilex Leaves Change with Long-Term Increased Drought Severity? Plant Cell Environ 2010, 33, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Sancho-Knapik, D.; Barrón, E.; Camarero, J.J.; Vilagrosa, A.; Gil-Pelegrín, E. Morphological and Physiological Divergences within Quercus ilex Support the Existence of Different Ecotypes Depending on Climatic Dryness. Ann. Bot. 2014, 114, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Poyatos, R.; Aguadé, D.; Retana, J.; Mencuccini, M. A New Look at Water Transport Regulation in Plants. New Phytol. 2014, 204, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F.; Lionello, P. Climate Change Projections for the Mediterranean Region. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2008, 63, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, W.; Guiot, J.; Fader, M.; Garrabou, J.; Gattuso, J.P.; Iglesias, A.; Lange, M.A.; Lionello, P.; Llasat, M.C.; Paz, S.; et al. Climate Change and Interconnected Risks to Sustainable Development in the Mediterranean. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 972–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Filella, I.; Estiarte, M.; Llusià, J.; Ogaya, R.; Carnicer, J.; Bartrons, M.; Rivas-Ubach, A.; Grau, O.; et al. Assessment of the Impacts of Climate Change on Mediterranean Terrestrial Ecosystems Based on Data from Field Experiments and Long-Term Monitored Field Gradients in Catalonia. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 152, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnicer, J.; Coll, M.; Ninyerola, M.; Pons, X.; Sánchez, G.; Peñuelas, J. Widespread Crown Condition Decline, Food Web Disruption, and Amplified Tree Mortality with Increased Climate Change-Type Drought. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1474–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilà-Cabrera, A.; Coll, L.; Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Retana, J. Forest Management for Adaptation to Climate Change in the Mediterranean Basin: A Synthesis of Evidence. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 407, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Pelegrín, E.; Saz, M.Á.; Cuadrat, J.M.; Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Sancho-Knapik, D. Oaks Under Mediterranean-Type Climates: Functional Response to Summer Aridity. In Oaks Physiological Ecology. Exploring the Functional Diversity of Genus Quercus L.; Gil-Pelegrín, E., Saz, M.Á., Cuadrat, J.M., Peguero-Pina, J.J., Sancho-Knapik, D., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 7, pp. 137–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Forn, D.; Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Ferrio, J.P.; Mencuccini, M.; Mendoza-Herrer, Ó.; Sancho-Knapik, D.; Gil-Pelegrín, E. Contrasting Functional Strategies Following Severe Drought in Two Mediterranean Oaks with Different Leaf Habit: Quercus faginea and Quercus ilex subsp. rotundifolia. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-e-Silva, F.; Correia, A.C.; Pinto, C.A.; David, J.S.; Hernandez-Santana, V.; David, T.S. Effects of Cork Oak Stripping on Tree Carbon and Water Fluxes. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 486, 118966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliach, D.; Vidale, E.; Brenko, A.; Marois, O.; Andrighetto, N.; Stara, K.; de Aragón, J.M.; Colinas, C.; Bonet, J.A. Truffle Market Evolution: An Application of the Delphi Method. Forests 2021, 12, 1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, S.; Garcia-Barreda, S. Black Truffle Cultivation: A Global Reality. For. Syst. 2014, 23, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čejka, T.; Isaac, E.L.; Oliach, D.; Martínez-Pea, F.; Egli, S.; Thomas, P.; Trnka, M.; Büntgen, U. Risk and Reward of the Global Truffle Sector under Predicted Climate Change. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, G.; Sourzat, P. Soils and Techniques for Cultivating Tuber melanosporum and Tuber aestivum in Europe. In Edible Ectomycorrhizal Mushrooms; Zambonelli, A., Bonito, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 34, pp. 163–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet, J.A.; Oliach, D.; Fischer, C.; Olivera, A.; Martínez de Aragón, J.M.; Colinas, C. Cultivation Methods of the Black Truffle, the Most Profitable Mediterranean Non-Wood Forest Product; A State of the Art Review. In Modelling, Valuing and Managing Mediterranean Forest Ecosystems for Non-Timber Goods and Services; Palahí, M., Birot, Y., Bravo, F., Gorriz, E., Eds.; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2009; pp. 57–71. ISBN 978-952-5453-27-0. [Google Scholar]

- Büntgen, U.; Egli, S.; Schneider, L.; von Arx, G.; Rigling, A.; Camarero, J.J.; Sangüesa-Barreda, G.; Fischer, C.R.; Oliach, D.; Bonet, J.A.; et al. Long-Term Irrigation Effects on Spanish Holm Oak Growth and Its Black Truffle Symbiont. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2015, 202, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, A.; Bonet, J.A.; Oliach, D.; Colinas, C. Time and Dose of Irrigation Impact Tuber melanosporum Ectomycorrhiza Proliferation and Growth of Quercus ilex Seedling Hosts in Young Black Truffle Orchards. Mycorrhiza 2014, 24, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.G. Irrigation Scheduling: Advantages and Pitfalls of Plant-Based Methods. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 2427–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipfer, T.; Bambach, N.; Isabel Hernandez, M.; Bartlett, M.K.; Sinclair, G.; Duong, F.; Kluepfel, D.A.; McElrone, A.J. Predicting Stomatal Closure and Turgor Loss in Woody Plants Using Predawn and Midday Water Potential. Plant Physiol. 2020, 184, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, A.; Masseroni, D.; Thalheimer, M.; de Medici, L.O.; Facchi, A. Field Irrigation Management through Soil Water Potential Measurements: A Review. Ital. J. Agrometeorol. 2017, 22, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Garcia-Forner, N. Water Potential Regulation, Stomatal Behaviour and Hydraulic Transport under Drought: Deconstructing the Iso/Anisohydric Concept. Plant Cell Environ. 2017, 40, 962–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, L.A.; Griseâ, D.J.; West, J.B.; Pappert, R.A.; Alder, N.N.; Richards, J.H. Predawn Disequilibrium between Plant and Soil Water Potentials in Two Cold-Desert Shrubs. Oecologia 1999, 120, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, S.J.; Scholz, F.G.; Goldstein, G.; Meinzer, F.C.; Hinojosa, J.A.; Hoffmann, W.A.; Franco, A.C. Processes Preventing Nocturnal Equilibration between Leaf and Soil Water Potential in Tropical Savanna Woody Species. Tree Physiol. 2004, 24, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, E.-D.; Hall, A.E. Stomatal Responses, Water Loss and CO2 Assimilation Rates of Plants in Contrasting Environments. In Physiological Plant Ecology II: Water Relations and Carbon Assimilation; Lange, O.L., Nobel, P.S., Osmond, C.B., Ziegler, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1982; pp. 181–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Améglio, T.; Archer, P.; Cohen, M.; Valancogne, C.; Daudet, F.-A.; Dayau, S.; Cruiziat, P. Significance and Limits in the Use of Predawn Leaf Water Potential for Tree Irrigation. Plant Soil 1999, 207, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Mangirón, M.; Ogaya, R.; Sauret, M.; Serrano, L.; Peñuelas, J.; Piñol, J. Sap Flow of Three Co-Occurring Mediterranean Woody Species under Varying Atmospheric and Soil Water Conditions. Tree Physiol. 2003, 23, 747–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, L.A.; Richards, J.H.; Linton, M.J. Magnitude and Mechanisms of Disequilibrium between Predawn Plant and Soil Water Potentials. Ecology 2003, 84, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, L.; Linton, M.; Richards, J. Predawn Plant Water Potential Does Not Necessarily Equilibrate with Soil Water Potential under Well-Watered Conditions. Oecologia 2001, 129, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellin, A. Does Pre-Dawn Water Potential Reflect Conditions of Equilibrium in Plant and Soil Water Status? Acta Oecol. 1999, 20, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, T.E.; Burgess, S.S.O.; Tu, K.P.; Oliveira, R.S.; Santiago, L.S.; Fisher, J.B.; Simonin, K.A.; Ambrose, A.R. Nighttime Transpiration in Woody Plants from Contrasting Ecosystems. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 561–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kangur, O.; Steppe, K.; Schreel, J.D.M.; Von Der Crone, J.S.; Sellin, A. Variation in Nocturnal Stomatal Conductance and Development of Predawn Disequilibrium between Soil and Leaf Water Potentials in Nine Temperate Deciduous Tree Species. Funct. Plant Biol. 2021, 48, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feild, T.S.; Holbrook, N.M. Xylem Sap Flow and Stem Hydraulics of the Vesselles Angiosperm Drimys granadensis (Winteraceae) in a Costa Rican Elfin Forest. Plant Cell Environ. 2000, 23, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.B.; Baldocchi, D.D.; Misson, L.; Dawson, T.E.; Goldstein, A.H. What the Towers Don’t See at Night: Nocturnal Sap Flow in Trees and Shrubs at Two AmeriFlux Sites in California. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caird, M.A.; Richards, J.H.; Donovan, L.A. Nighttime Stomatal Conductance and Transpiration in C3 and C4 Plants. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender-Bares, J.; Sack, L.; Savage, J. Atmospheric and Soil Drought Reduce Nocturnal Conductance in Live Oaks. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, T.S.; Henriques, M.O.; Kurz-Besson, C.; Nunes, J.; Valente, F.; Vaz, M.; Pereira, J.S.; Siegwolf, R.; Chaves, M.M.; Gazarini, L.C.; et al. Water-Use Strategies in Two Co-Occurring Mediterranean Evergreen Oaks: Surviving the Summer Drought. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbeta, A.; Ogaya, R.; Peñuelas, J. Comparative Study of Diurnal and Nocturnal Sap Flow of Quercus ilex and Phillyrea latifolia in a Mediterranean Holm Oak Forest in Prades (Catalonia, NE Spain). Trees—Struct. Funct. 2012, 26, 1651–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, M.; Pereira, J.S.; Gazarini, L.C.; David, T.S.; David, J.S.; Rodrigues, A.; Maroco, J.; Chaves, M.M. Drought-Induced Photosynthetic Inhibition and Autumn Recovery in Two Mediterranean Oak Species (Quercus ilex and Quercus suber). Tree Physiol. 2010, 30, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, C.A.; David, J.S.; Cochard, H.; Caldeira, M.C.; Henriques, M.O.; Quilhó, T.; Paço, T.A.; Pereira, J.S.; David, T.S. Drought-Induced Embolism in Current-Year Shoots of Two Mediterranean Evergreen Oaks. For. Ecol. Manag. 2012, 285, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Sancho-Knapik, D.; Morales, F.; Flexas, J.; Gil-Pelegrin, E. Differential Photosynthetic Performance and Photoprotection Mechanisms of Three Mediterranean Evergreen Oaks under Severe Drought Stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 2009, 36, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Filella, I.; Estiarte, M.; Llusià, J.; Ogaya, R.; Carnicer, J.; Bartrons, M.; Rivas-Ubach, A.; Grau, O.; et al. Impacts of Global Change on Mediterranean Forests and Their Services. Forests 2017, 8, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Tejera, O.; López-Bernal, Á.; Orgaz, F.; Testi, L.; Villalobos, F.J. The Pitfalls of Water Potential for Irrigation Scheduling. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 243, 106522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundel, P.W.; Jarrell, W.M. Water in the Environment. In Plant Physiological Ecology: Field Methods and Instrumentation; Pearcy, R., Ehleringer, J., Mooney, H., Rundel, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherland; London, UK, 1989; pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.C. Measurement of Plant Water Status by the Pressure Chamber Technique. Irrig. Sci. 1988, 9, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangur, O.; Kupper, P.; Sellin, A. Predawn Disequilibrium between Soil and Plant Water Potentials in Light of Climate Trends Predicted for Northern Europe. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 2159–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, version 2024.12.0; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 1–608. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, F. DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level/Mixed) Regression Models, version 0.4.7, R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DHARMa (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Lenth, R. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means, version 1.10.6, R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Bréda, N.; Granier, A.; Barataud, F.; Moyne, C. Soil Water Dynamics in an Oak Stand. Plant Soil 1995, 172, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, H.A.; Rico, M.; Moreno, G.; Santa Regina, I. Leaf Water Potential and Stomatal Conductance in Quercus pyrenaica Willd. Forests: Vertical Gradients and Response to Environmental Factors. Tree Physiol. 1993, 14, 1039–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucci, S.J.; Goldstein, G.; Meinzer, F.C.; Franco, A.C.; Campanello, P.; Scholz, F.G. Mechanisms Contributing to Seasonal Homeostasis of Minimum Leaf Water Potential and Predawn Disequilibrium between Soil and Plant Water Potential in Neotropical Savanna Trees. Trees—Struct. Funct. 2005, 19, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, S.Y.; Greer, D.H.; Hatfield, J.M.; Hutton, R.J.; Clarke, S.J.; Hutchinson, P.A.; Somers, A. Stomatal Response of an Anisohydric Grapevine Cultivar to Evaporative Demand, Available Soil Moisture and Abscisic Acid. Tree Physiol. 2012, 32, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppel, M.J.B.; Lewis, J.D.; Phillips, N.G.; Tissue, D.T. Consequences of Nocturnal Water Loss: A Synthesis of Regulating Factors and Implications for Capacitance, Embolism and Use in Models. Tree Physiol. 2014, 34, 1047–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dios, V.R.; Roy, J.; Ferrio, J.P.; Alday, J.G.; Landais, D.; Milcu, A.; Gessler, A. Processes Driving Nocturnal Transpiration and Implications for Estimating Land Evapotranspiration. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resco, V.; Hartwell, J.; Hall, A. Ecological Implications of Plants’ Ability to Tell the Time. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstiens, G. Cuticular Water Permeability and Its Physiological Significance. J. Exp. Bot. 1996, 47, 1813–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardini, A.; Tyree, M.T. Root and Shoot Hydraulic Conductance of Seven Quercus Species. Ann. For. Sci. 1999, 56, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tognetti, R.; Longobucco, A.; Raschi, A. Vulnerability of Xylem to Embolism in Relation to Plant Hydraulic Resistance in Quercus pubescens and Quercus ilex Co-Occurring in a Mediterranean Coppice Stand in Central Italy. New Phytol. 1998, 139, 437–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodribb, T.J.; McAdam, S.A.M.; Jordan, G.J.; Martins, S.C.V. Conifer Species Adapt to Low-Rainfall Climates by Following One of Two Divergent Pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 14489–14493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bréda, N.; Cochard, H.; Dreyer, E.; Granier, A. Water Transfer in a Mature Oak Stand (Quercus petraea): Seasonal Evolution and Effects of a Severe Drought. Can. J. For. Res. 1993, 23, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochard, H.; Bréda, N.; Granier, A. Whole Tree Hydraulic Conductance and Water Loss Regulation in Quercus during Drought: Evidence for Stomatal Control of Embolism? Ann. Sci. For. 1996, 53, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardini, A.; Casolo, V.; Dal Borgo, A.; Savi, T.; Stenni, B.; Bertoncin, P.; Zini, L.; Mcdowell, N.G. Rooting Depth, Water Relations and Non-Structural Carbohydrate Dynamics in Three Woody Angiosperms Differentially Affected by an Extreme Summer Drought. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcuera, L.; Camarero, J.J.; Gil-Pelegrín, E. Effects of a Severe Drought on Quercus ilex Radial Growth and Xylem Anatomy. Trees—Struct. Funct. 2004, 18, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaz, M.; Cochard, H.; Gazarini, L.; Graça, J.; Chaves, M.M.; Pereira, J.S. Cork Oak (Quercus suber L.) Seedlings Acclimate to Elevated CO2 and Water Stress: Photosynthesis, Growth, Wood Anatomy and Hydraulic Conductivity. Trees—Struct. Funct. 2012, 26, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quero, J.L.; Villar, R.; Marañón, T.; Zamora, R. Interactions of Drought and Shade Effects on Seedlings of Four Quercus Species: Physiological and Structural Leaf Responses. New Phytol. 2006, 170, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peguero-Pina, J.J.; Mendoza-Herrer, Ó.; Gil-Pelegrín, E.; Sancho-Knapik, D. Cavitation Limits the Recovery of Gas Exchange after Severe Drought Stress in Holm Oak (Quercus ilex L.). Forests 2018, 9, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmés, J.; Medrano, H.; Flexas, J. Photosynthetic Limitations in Response to Water Stress and Recovery in Mediterranean Plants with Different Growth Forms. New Phytol. 2007, 175, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-StPaul, N.; Delzon, S.; Cochard, H. Plant Resistance to Drought Depends on Timely Stomatal Closure. Ecol. Lett. 2017, 20, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Salvador, P.; Puértolas, J.; Cuesta, B.; Peñuelas, J.L.; Uscola, M.; Heredia-Guerrero, N.; Rey Benayas, J.M. Increase in Size and Nitrogen Concentration Enhances Seedling Survival in Mediterranean Plantations. Insights from an Ecophysiological Conceptual Model of Plant Survival. New For. 2012, 43, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Valiente, J.A.; Aranda, I.; Sanchéz-Gómez, D.; Rodríguez-Calcerrada, J.; Valladares, F.; Robson, T.M. Increased Root Investment Can Explain the Higher Survival of Seedlings of “mesic” Quercus suber than “Xeric” Quercus ilex in Sandy Soils during a Summer Drought. Tree Physiol. 2018, 39, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, I.; Bergantino, E.; Giacometti, G.M. Light and Oxygenic Photosynthesis: Energy Dissipation as a Protection Mechanism against Photo-Oxidation. EMBO Rep. 2005, 6, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC Sections. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.N.; Jin, H.Y.; Kwak, M.J.; Khaine, I.; You, H.N.; Lee, T.Y.; Ahn, T.H.; Woo, S.Y. Why Does Quercus suber Species Decline in Mediterranean Areas? J. Asia Pac. Biodivers. 2017, 10, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito Garzón, M.; Sánchez De Dios, R.; Sainz Ollero, H. Effects of Climate Change on the Distribution of Iberian Tree Species. Appl. Veg. Sci. 2008, 11, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Valiente, J.A.; Valladares, F.; Gil, L.; Aranda, I. Population Differences in Juvenile Survival under Increasing Drought Are Mediated by Seed Size in Cork Oak (Quercus suber L.). For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 1676–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, V.; Navarro-Cerrillo, R.M.; Villar, R. Artificial Regeneration with Quercus ilex L. and Quercus suber L. by Direct Seeding and Planting in Southern Spain. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantis, F.; Graap, J.; Früchtenicht, E.; Bussotti, F.; Radoglou, K.; Brüggemann, W. Field Performances of Mediterranean Oaks in Replicate Common Gardens for Future Reforestation under Climate Change in Central and Southern Europe: First Results from a Four-Year Study. Forests 2021, 12, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivera, A.; Fischer, C.R.; Bonet, J.A.; de Aragón, J.M.; Oliach, D.; Colinas, C. Weed Management and Irrigation Are Key Treatments in Emerging Black Truffle (Tuber melanosporum) Cultivation. New For. 2011, 42, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | spp. | N | Formula | Df | AIC | logLik |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lmm0-Qi | Q. ilex | 3 | PDD~1 + (1|Pot) | - | 138.28 | −66.141 |

| lmm1-Qi | Q. ilex | 4 | PDD~H + (1|Pot) | 1 | 120.690 | −56.344 |

| lmm2-Qi | Q. ilex | 5 | PDD~H + ΨS + (1|Pot) | 1 | 118.620 | −54.313 |

| lmm3-Qi | Q. ilex | 6 | PDD~H + ΨS + E + (1|Pot) | 1 | 120.610 | −54.308 |

| lmm4-Qi | Q. ilex | 6 | PDD~H + ΨS + VPD + (1|Pot) | 0 | 118.950 | −53.476 |

| lmm1-Qs | Q. suber | 3 | PDD~1 + (1|Pot) | - | 102.988 | −48.494 |

| lmm2-Qs | Q. suber | 4 | PDD~ΨS + (1|Pot) | 1 | 80.188 | −36.094 |

| lmm3-Qs | Q. suber | 5 | PDD~ΨS + H + (1|Pot) | 1 | 82.060 | −36.030 |

| lmm4-Qs | Q. suber | 5 | PDD~ΨS + E + (1|Pot) | 0 | 80.869 | −35.435 |

| lmm5-Qs | Q. suber | 5 | PDD~ΨS + VPD + (1|Pot) | 0 | 82.186 | −36.093 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Pruñanosa, M.; Albó, D.; Meijer, A.; Pérez-Llorca, M.; Colinas, C. Predawn Disequilibrium Between Soil and Plant Water Potentials in Seedlings of Two Mediterranean Oak Species (Quercus ilex and Quercus suber). Forests 2026, 17, 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010049

Pruñanosa M, Albó D, Meijer A, Pérez-Llorca M, Colinas C. Predawn Disequilibrium Between Soil and Plant Water Potentials in Seedlings of Two Mediterranean Oak Species (Quercus ilex and Quercus suber). Forests. 2026; 17(1):49. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010049

Chicago/Turabian StylePruñanosa, Marc, Dalmau Albó, Andreu Meijer, Marina Pérez-Llorca, and Carlos Colinas. 2026. "Predawn Disequilibrium Between Soil and Plant Water Potentials in Seedlings of Two Mediterranean Oak Species (Quercus ilex and Quercus suber)" Forests 17, no. 1: 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010049

APA StylePruñanosa, M., Albó, D., Meijer, A., Pérez-Llorca, M., & Colinas, C. (2026). Predawn Disequilibrium Between Soil and Plant Water Potentials in Seedlings of Two Mediterranean Oak Species (Quercus ilex and Quercus suber). Forests, 17(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010049