Analysis of Genetic Structure in Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. GBS Assay and SNP Filtering

2.3. Genetic Structure Analysis

3. Results

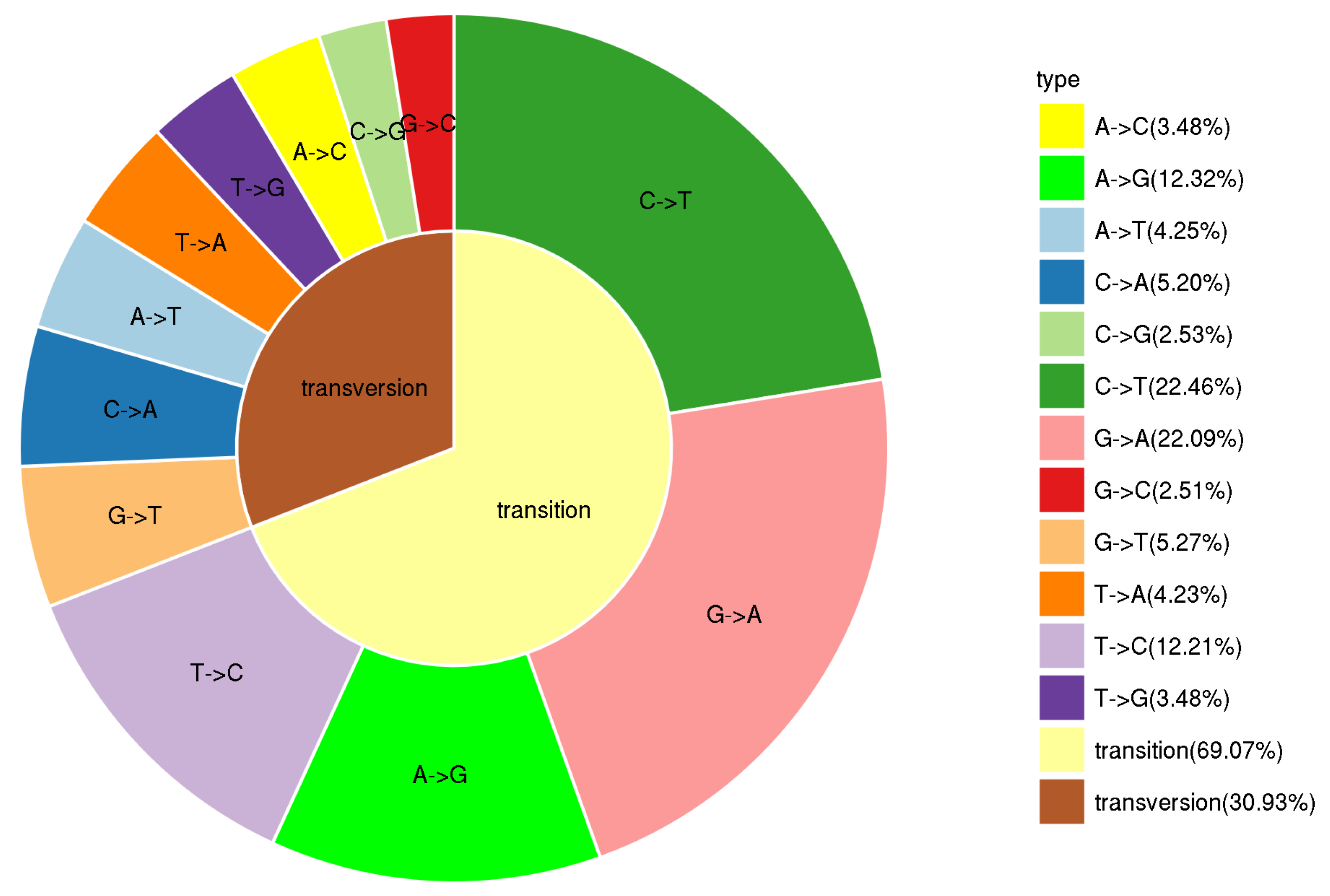

3.1. Genome-Wide SNP Discovery and Characterization

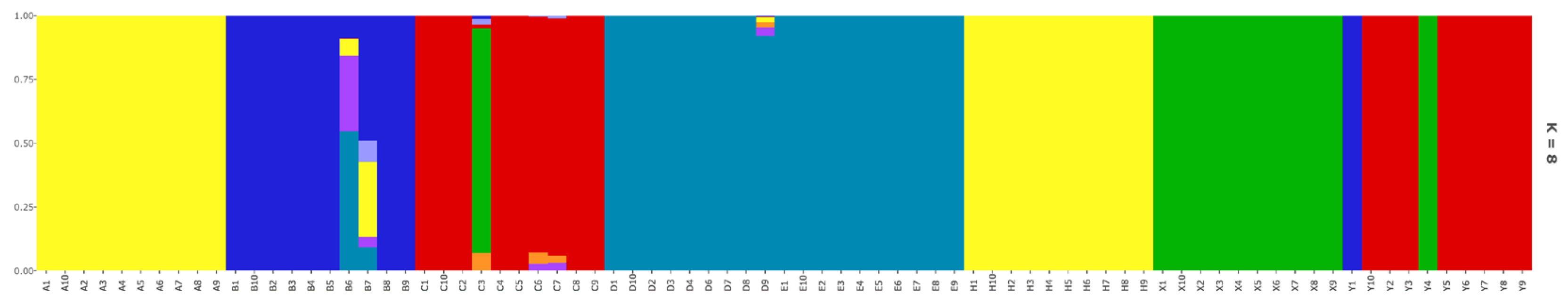

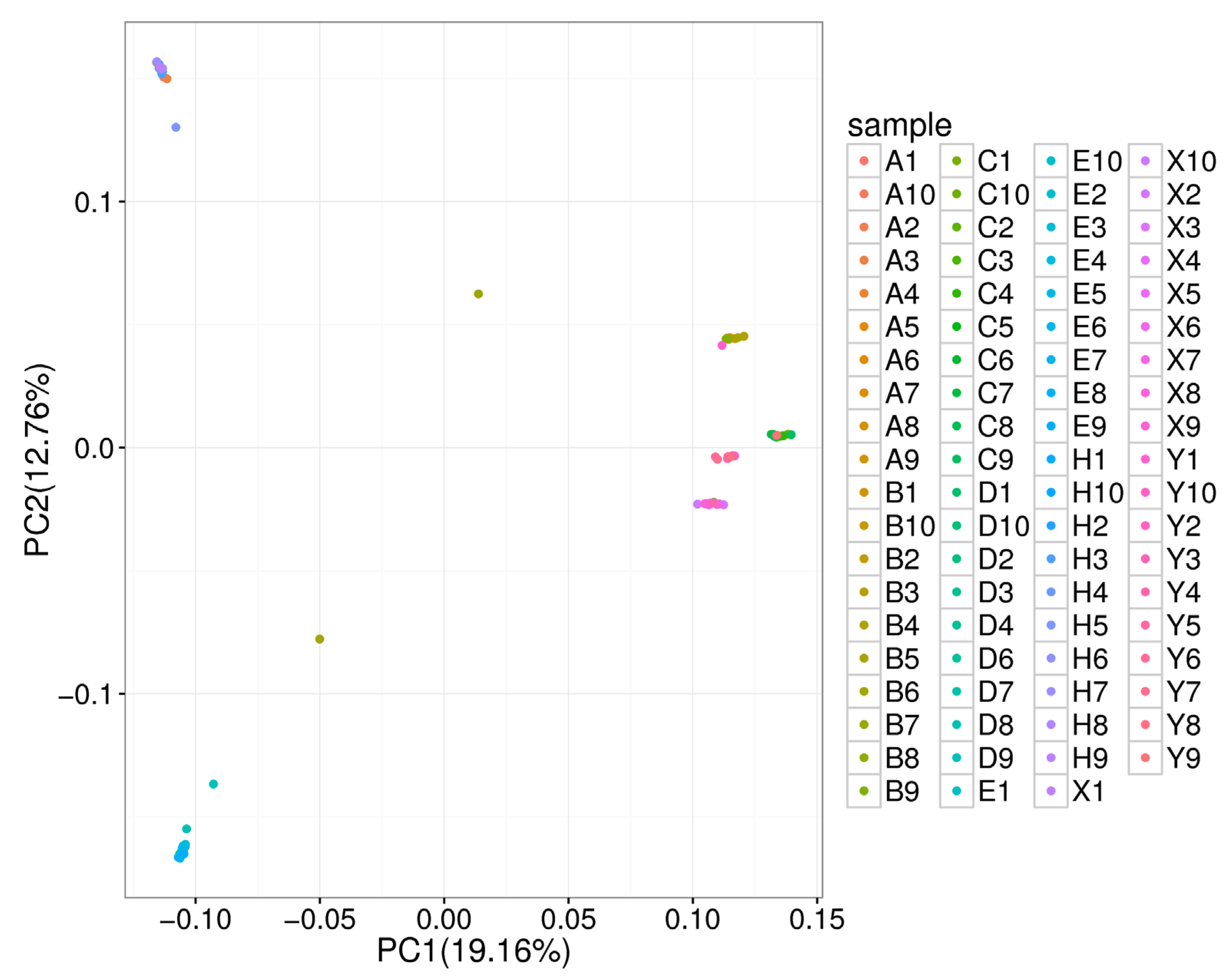

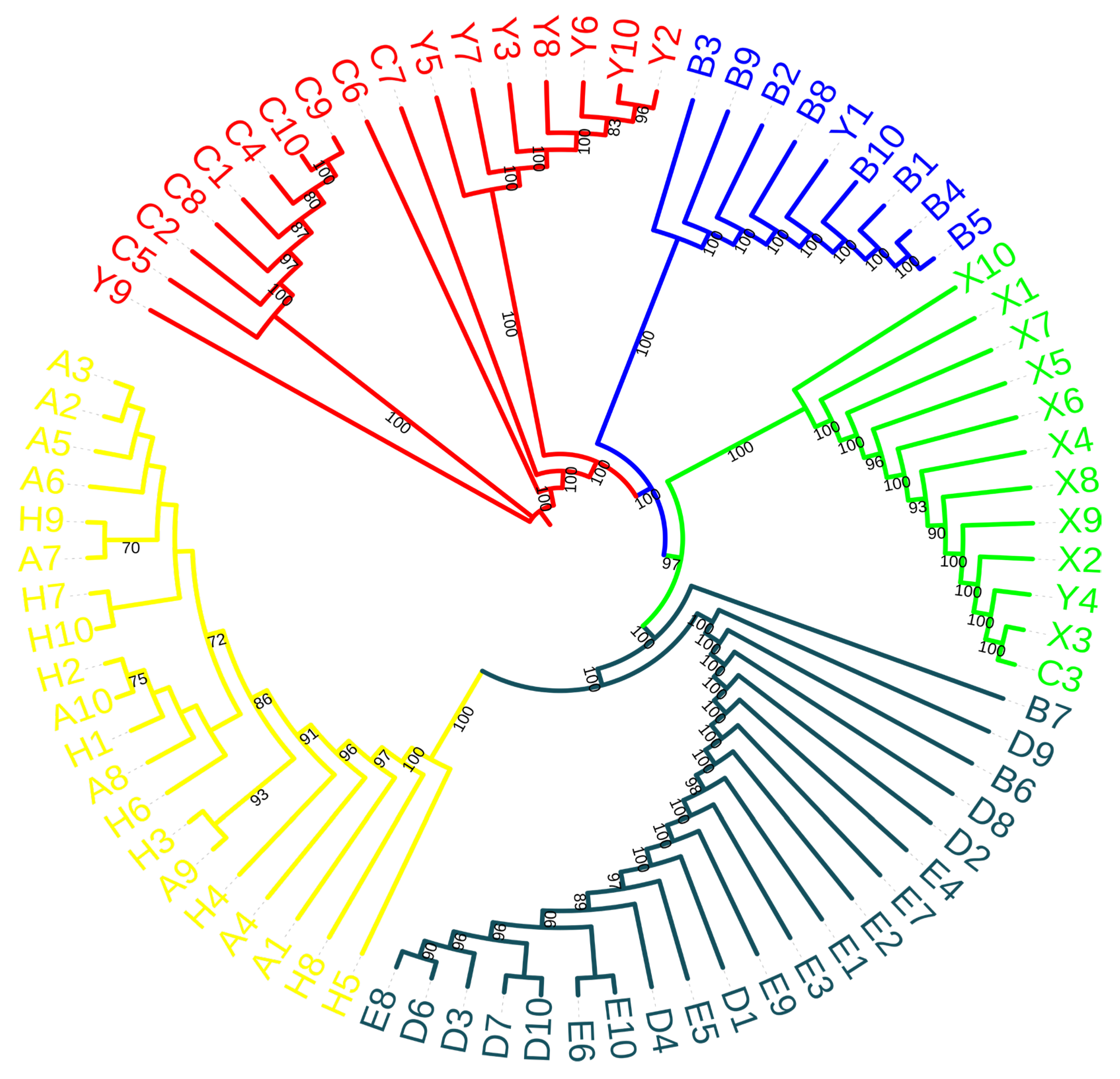

3.2. Genetic Structure and Relationship

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, P.; Lu, H.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Shen, Q.; Kant, S.; Sun, S.; et al. Trichoderma Bio-Organic Fertilizer Enhances Ornamental Value of Ilex verticillata. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 350, 114348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Nisar, M.; Shah, S.W.A.; Khalil, A.A.K.; Zahoor, M.; Nazir, N.; Shah, S.A.; Nasr, F.A.; Noman, O.M.; Mothana, R.A.; et al. Anatomical Characterization, HPLC Analysis, and Biological Activities of Ilex dipyrena. Plants 2022, 11, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.-Q.; Wu, C.-N.; Song, Y.; Jiang, H.-Q.; Zhou, H.-L.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.-F.; Zhang, X.-L.; Wu, Y. Chemical Constituents from Ilex urceolatus. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2016, 64, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, E.; Okińczyc, P.; Zwyrzykowska-Wodzińska, A.; Szperlik, J.; Żarowska, B.; Duda-Madej, A.; Bąbelewski, P.; Włodarczyk, M.; Wojtasik, W.; Kupczyński, R.; et al. Composition and Antimicrobial Activity of Ilex Leaves Water Extracts. Molecules 2021, 26, 7442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachura, N.; Włodarczyk, M.; Bażanów, B.; Pogorzelska, A.; Gębarowski, T.; Kupczyński, R.; Szumny, A. Antiviral and Cytotoxic Activities of Ilex aquifolium Silver Queen in the Context of Chemical Profiling of Two Ilex Species. Molecules 2024, 29, 3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhu, J.-P.; Rong, L.; Jin, J.; Cao, D.; Li, H.; Zhou, X.-H.; Zhao, Z.-X. Triterpenoids with Antiplatelet Aggregation Activity from Ilex rotunda. Phytochemistry 2018, 145, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.-Q.; Li, R.-F.; Liu, J.-B.; Cui, B.-S.; Hou, Q.; Sun, H.; Li, S. Triterpenoids from the Leaves of Ilex chinensis. Phytochemistry 2018, 148, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, F.; Yousif, M.; Huang, R.; Qiao, Y.; Hu, Y. Network Pharmacology- and Molecular Docking-Based Analyses of the Antihypertensive Mechanism of Ilex kudingcha. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1216086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Xiao, J.; Chen, G.; Li, N. Natural CAC Chemopreventive Agents from Ilex rotunda Thunb. J. Nat. Med. 2019, 73, 456–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachura, N.; Kupczyński, R.; Sycz, J.; Kuklińska, A.; Zwyrzykowska-Wodzińska, A.; Wińska, K.; Owczarek, A.; Kuropka, P.; Nowaczyk, R.; Bąbelewski, P.; et al. Biological Potential and Chemical Profile of European Varieties of Ilex. Foods 2021, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, P. Epigenetic Variation and Environmental Change. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 66, 3541–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpal, V.R.; Rathore, P.; Mehta, S.; Wadhwa, N.; Yadav, P.; Berry, E.; Goel, S.; Bhat, V.; Raina, S.N. Epigenetic Variation: A Major Player in Facilitating Plant Fitness under Changing Environmental Conditions. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1020958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cascales, J.; Acevedo, R.M.; Paiva, D.I.; Gottlieb, A.M. Differential DNA Methylation and Gene Expression during Development of Reproductive and Vegetative Organs in Ilex Species. J. Plant. Res. 2021, 134, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, A.S.M.F.; Sanders, D.; Mishra, A.K.; Joshi, V. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure Analysis of the USDA Olive Germplasm Using Genotyping-By-Sequencing (GBS). Genes 2021, 12, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muli, J.K.; Neondo, J.O.; Kamau, P.K.; Michuki, G.N.; Odari, E.; Budambula, N.L.M. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Wild and Cultivated Crotalaria Species Based on Genotyping-by-Sequencing. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhao, X.; Laroche, A.; Lu, Z.-X.; Liu, H.; Li, Z. Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS), an Ultimate Marker-Assisted Selection (MAS) Tool to Accelerate Plant Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.S.; Choi, S.C.; Jun, T.-H.; Kim, C. Genotyping-by-Sequencing: A Promising Tool for Plant Genetics Research and Breeding. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2017, 58, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.; Wu, Y.; McCurdy, J.D.; Stewart, B.R.; Warburton, M.L.; Baldwin, B.S.; Dong, H. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure of Bermudagrass (Cynodon spp.) Revealed by Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1155721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Song, Q.; Koiwa, H.; Qiao, D.; Zhao, D.; Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Wen, X. Genetic Diversity, Linkage Disequilibrium, and Population Structure Analysis of the Tea Plant (Camellia sinensis) from an Origin Center, Guizhou Plateau, Using Genome-Wide SNPs Developed by Genotyping-by-Sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.-H.; Gil, H.-Y.; Kim, S.-C.; Choi, K.; Kim, J.-H. Genetic Structure and Geneflow of Malus across the Korean Peninsula Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Pang, X.; Li, Y. Genome-wide Association Studies of Fruit Quality Traits in Jujube Germplasm Collections Using Genotyping-by-sequencing. Plant Genome 2020, 13, e20036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pootakham, W.; Ruang-Areerate, P.; Jomchai, N.; Sonthirod, C.; Sangsrakru, D.; Yoocha, T.; Theerawattanasuk, K.; Nirapathpongporn, K.; Romruensukharom, P.; Tragoonrung, S.; et al. Construction of a High-Density Integrated Genetic Linkage Map of Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis) Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS). Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavan, S.; Curci, P.L.; Zuluaga, D.L.; Blanco, E.; Sonnante, G. Genotyping-by-Sequencing Highlights Patterns of Genetic Structure and Domestication in Artichoke and Cardoon. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Niu, S.; Deng, X.; Song, Q.; He, L.; Bai, D.; He, Y. Genome-Wide Association Study of Leaf-Related Traits in Tea Plant in Guizhou Based on Genotyping-by-Sequencing. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishor, D.S.; Noh, Y.; Song, W.-H.; Lee, G.P.; Park, Y.; Jung, J.-K.; Shim, E.-J.; Sim, S.-C.; Chung, S.-M. SNP Marker Assay and Candidate Gene Identification for Sex Expression via Genotyping-by-Sequencing-Based Genome-Wide Associations (GWAS) Analyses in Oriental Melon (Cucumis melo L. Var. makuwa). Sci. Hortic. 2021, 276, 109711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossa, J.; Beyene, Y.; Kassa, S.; Pérez, P.; Hickey, J.M.; Chen, C.; De Los Campos, G.; Burgueño, J.; Windhausen, V.S.; Buckler, E.; et al. Genomic Prediction in Maize Breeding Populations with Genotyping-by-Sequencing. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2013, 3, 1903–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalew, H.; Anderson, J.D.; Krom, N.; Tang, Y.; Butler, T.J.; Rawat, N.; Tiwari, V.; Ma, X.-F. Genotyping-by-Sequencing and Genomic Selection Applications in Hexaploid Triticale. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2022, 12, jkab413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, N.; Grauke, L.J.; Klein, P. Genotyping by Sequencing (GBS) and SNP Marker Analysis of Diverse Accessions of Pecan (Carya illinoinensis). Tree Genet. Genomes 2019, 15, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klápště, J.; Ashby, R.L.; Telfer, E.J.; Graham, N.J.; Dungey, H.S.; Brauning, R.; Clarke, S.M.; Dodds, K.G. The Use of “Genotyping-by-Sequencing” to Recover Shared Genealogy in Genetically Diverse Eucalyptus Populations. Forests 2021, 12, 904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.; Zhao, W.; Wennström, U.; Andersson Gull, B.; Wang, X.-R. Parentage and Relatedness Reconstruction in Pinus sylvestris Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Heredity 2020, 124, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Tan, Y.-H.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Song, Y.; Yang, J.-B.; Corlett, R.T. Chloroplast Genome Structure in Ilex (Aquifoliaceae). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, D.; Del Guacchio, E.; Cennamo, P.; Paino, L.; Caputo, P. Genotyping-by-Sequencing Provides New Genetic and Taxonomic Insights in the Critical Group of Centaurea tenorei. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1130889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Li, N.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, W.; Yang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, R. Molecular Evidence for the Hybrid Origin of Ilex dabieshanensis (Aquifoliaceae). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvento, C.; Pavan, S.; Miazzi, M.M.; Marcotrigiano, A.R.; Ricciardi, F.; Ricciardi, L.; Lotti, C. Genotyping-by-Sequencing Defines Genetic Structure within the “Acquaviva” Red Onion Landrace. Plants 2022, 11, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, U.V.T.; Tamiru-Oli, M.; Hurgobin, B.; Okey, C.R.; Abreu, A.R.; Lewsey, M.G. Insights into Opium Poppy (Papaver spp.) Genetic Diversity from Genotyping-by-Sequencing Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fang, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, T.; Kou, K.; Su, T.; Li, S.; Chen, L.; Cheng, Q.; Dong, L.; et al. Identification of Major QTLs for Flowering and Maturity in Soybean by Genotyping-by-Sequencing Analysis. Mol. Breed. 2020, 40, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. Fastp: An Ultra-Fast All-in-One FASTQ Preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catchen, J.; Hohenlohe, P.A.; Bassham, S.; Amores, A.; Cresko, W.A. Stacks: An Analysis Tool Set for Population Genomics. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 3124–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePristo, M.A.; Banks, E.; Poplin, R.; Garimella, K.V.; Maguire, J.R.; Hartl, C.; Philippakis, A.A.; Del Angel, G.; Rivas, M.A.; Hanna, M.; et al. A Framework for Variation Discovery and Genotyping Using Next-Generation DNA Sequencing Data. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, D.H.; Novembre, J.; Lange, K. Fast Model-Based Estimation of Ancestry in Unrelated Individuals. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C.; Chow, C.C.; Tellier, L.C.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S.M.; Lee, J.J. Second-Generation PLINK: Rising to the Challenge of Larger and Richer Datasets. Gigascience 2015, 4, s13742-015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, R.M. POPHELPER: An R Package and Web App to Analyse and Visualize Population Structure. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017, 17, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Lee, S.H.; Goddard, M.E.; Visscher, P.M. GCTA: A Tool for Genome-Wide Complex Trait Analysis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 88, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasawa, K.; Kuwata, C.; Watanabe, M.; Fukami, M.; Hirakawa, H.; Isobe, S. Target Amplicon Sequencing for Genotyping Genome-Wide Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms Identified by Whole-Genome Resequencing in Peanut. Plant Genome 2016, 9, plantgenome2016.06.0052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, S.; Llaca, V.; May, G.D. Genotyping-by-Sequencing in Plants. Biology 2012, 1, 460–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Zhou, P.; Fang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Q. The Genetic Diversity of Natural Ilex chinensis Sims (Aquifoliaceae) Populations as Revealed by SSR Markers. Forests 2024, 15, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, C.; Fernández, V.; Gil, L.; Valbuena-Carabaña, M. Clonal Diversity and Fine-Scale Genetic Structure of a Keystone Species: Ilex aquifolium. Forests 2022, 13, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascales, J.; Bracco, M.; Garberoglio, M.; Poggio, L.; Gottlieb, A. Integral Phylogenomic Approach over Ilex L. Species from Southern South America. Life 2017, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, T.; Farrelly, N.; Kelleher, C.; Hodkinson, T.R.; Byrne, S.L.; Barth, S. Genetic Diversity and Structure of a Diverse Population of Picea sitchensis Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Forests 2022, 13, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Ma, X.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, J. Population Genetics and Origin of Horticultural Germplasm in Clematis via Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sork, V.L. Genomic Studies of Local Adaptation in Natural Plant Populations. J. Hered. 2017, 109, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.K.; Ha, S.T.T.; Lim, J.H. Analysis of Chrysanthemum Genetic Diversity by Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2020, 61, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Jung, J.-A.; Lee, N.H.; Kim, J.S.; Won, S.Y. Genetic Analysis of Anemone-Type and Single-Type Inflorescences in Chrysanthemum Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Euphytica 2022, 218, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, R.; Nemati, Z.; Naghavi, M.R.; Pfanzelt, S.; Rahimi, A.; Kanzagh, A.G.; Blattner, F.R. Phylogeography and Genetic Structure of Papaver bracteatum Populations in Iran Based on Genotyping-by-Sequencing (GBS). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cros, D.; Bocs, S.; Riou, V.; Ortega-Abboud, E.; Tisné, S.; Argout, X.; Pomiès, V.; Nodichao, L.; Lubis, Z.; Cochard, B.; et al. Genomic Preselection with Genotyping-by-Sequencing Increases Performance of Commercial Oil Palm Hybrid Crosses. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID Range | Cultivar Name | Origin Country | Source Province City |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1–A10 | Ilex verticillata ‘Winter Gold’ | USA | Shandong Rizhao |

| B1–B10 | Ilex verticillata ‘Golden Verboom’ | The Netherlands | Shandong Rizhao |

| C1–C10 | Ilex verticillata ‘Red Sprite’ | USA | Shandong Rizhao |

| D1–D4, D6–D10 | Ilex verticillata ‘Citronella’ | USA | Shandong Rizhao |

| E1–E10 | Ilex verticillata ‘Oosterwijk’ | The Netherlands | Jiangsu Nanjing |

| H1–H10 | Ilex verticillata ‘Winter Red’ | USA | Jiangsu Nanjing |

| X1–X10 | Ilex verticillata ‘Little Goblin Red’ | USA | Shandong Dezhou |

| Y1–Y10 | Ilex verticillata ‘Red Sprite’ | USA | Shandong Dezhou |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hao, M.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, X. Analysis of Genetic Structure in Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Forests 2026, 17, 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010047

Hao M, Fan Y, Zhao X, Zhao X. Analysis of Genetic Structure in Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Forests. 2026; 17(1):47. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010047

Chicago/Turabian StyleHao, Mingzhuo, Yizhuo Fan, Xiaonan Zhao, and Xueqing Zhao. 2026. "Analysis of Genetic Structure in Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing" Forests 17, no. 1: 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010047

APA StyleHao, M., Fan, Y., Zhao, X., & Zhao, X. (2026). Analysis of Genetic Structure in Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) Using Genotyping-by-Sequencing. Forests, 17(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010047