Modeling Commercial Height in Amazonian Forests: Accuracy of Mixed-Effects Regression Versus Random Forest

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Database and Analysis

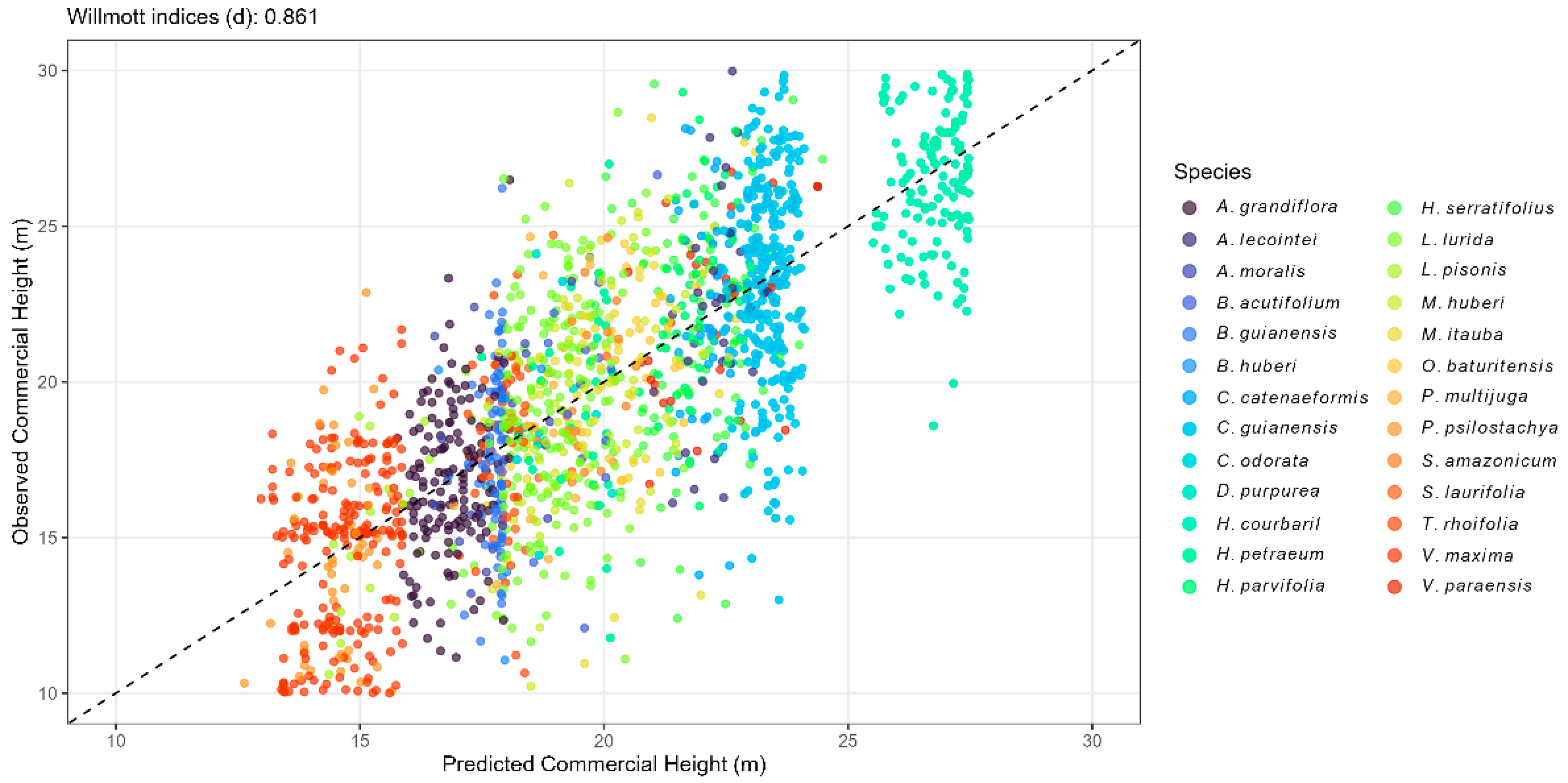

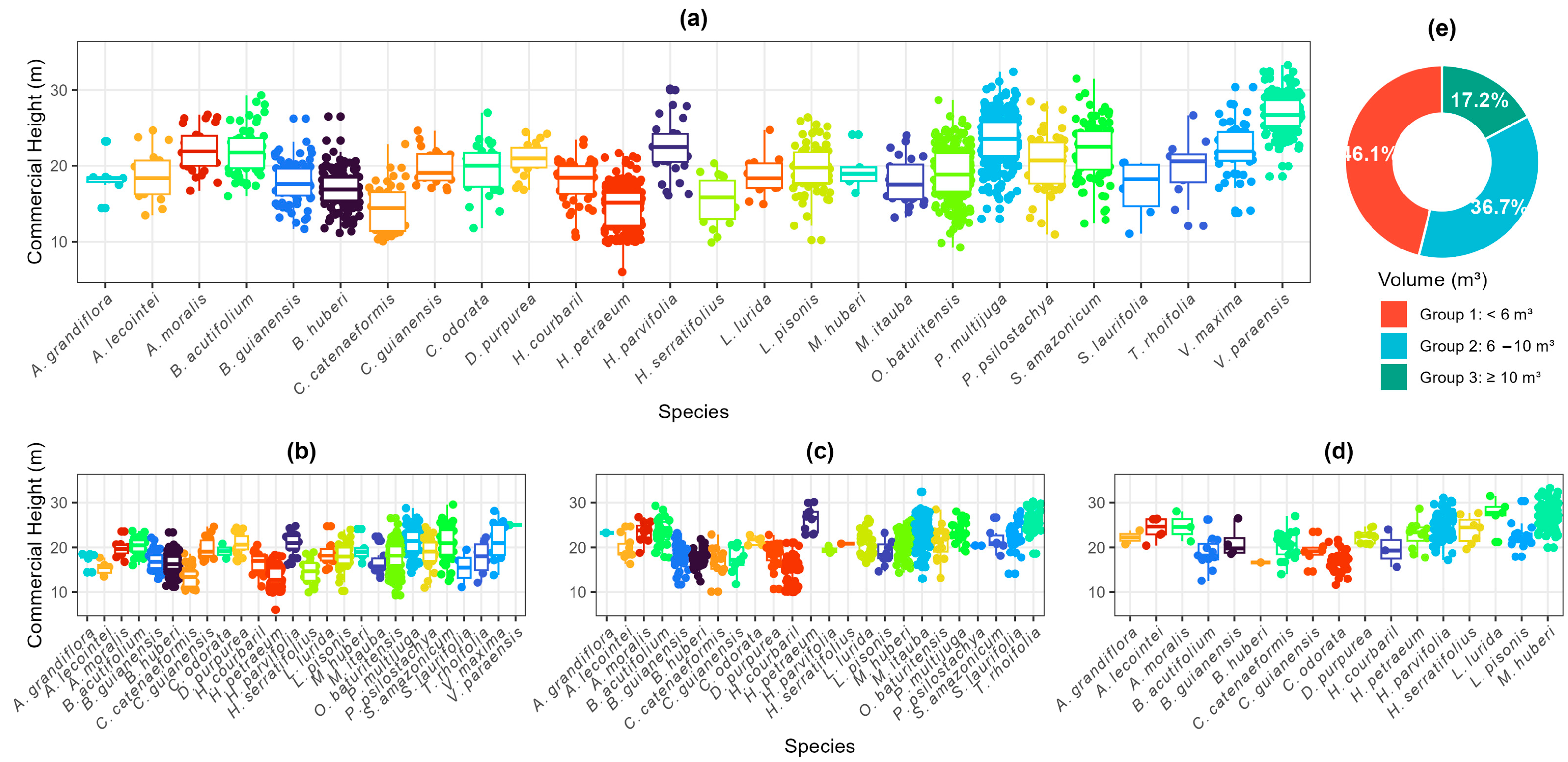

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malhi, Y.; Roberts, J.T.; Betts, R.A.; Killeen, T.J.; Li, W.; Nobre, C.A. Climate change, deforestation and the fate of the Amazon. Science 2008, 319, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Malhi, Y.; Barbier, N.; Lima, A.; Shimabukuro, Y.; Anderson, L.; Costa, M. Environmental change and the carbon balance of Amazonian forests. Biol. Rev. 2014, 89, 913–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemp, D.C.; Schleussner, C.F.; Barbosa, H.M.J.; Rammig, A. Deforestation effects on Amazon forest resilience. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2017, 44, 6182–6190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, T.E.; Nobre, C. Amazon tipping point: Last chance for action. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaba2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, J.K. Modelling Forest Growth and Yield: Applications to Mixed Tropical Forests; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Putz, F.E.; Zuidema, P.A.; Pinard, M.A.; Boot, R.G.A.; Sayer, J.A.; Sheil, D.; Sist, P.; Elias, M.; Vanclay, J.K. Improved tropical forest management for carbon retention. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sist, P.; Ferreira, F.N. Sustainability of reduced-impact logging in the Eastern Amazon. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 243, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, J.C.C.; Leite, H.G. Mensuração Florestal: Perguntas e Respostas, 5th ed.; Editora UFV: Viçosa, MG, Brazil, 2017; p. 636. [Google Scholar]

- Putz, F.E.; Zuidema, P.A.; Synnott, T.; Peña-Claros, M.; Pinard, M.A.; Sheil, D.; Vanclay, J.K.; Sist, P.; Gourlet-Fleury, S.; Griscom, B.; et al. Sustaining conservation values in selectively logged tropical forests: The attained and the attainable. Conserv. Lett. 2012, 5, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lehtomäki, M.; Liang, X.; Pyörälä, J.; Kukko, A.; Jaakkola, A.; Liu, J.; Feng, Z.; Chen, R.; Hyyppä, J. Is field-measured tree height as reliable as believed—A comparison study of tree height estimates from field measurement, airborne laser scanning and terrestrial laser scanning in a boreal forest. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 147, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugasha, W.A.; Bollandsås, O.M.; Eid, T. Relationships between diameter and height of trees in natural tropical forest in Tanzania. South. For. 2013, 75, 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, P.A.; Romarco, M.L.; Cardoso, J.F.; Vilas-Boas, M.N.; Azevedo, L.R.; Silva, A.V.S. Estimativa de altura por meio de modelos hipsométricos de um povoamento de Schizolobium amazonicum Huber ex Ducke (Fabaceae) em Minas Gerais. Série Técnica IPEF 2023, 26, 554–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, K.; Zakrzewski, W.T. Practical approaches to calibrating height-diameter relationships for natural sugar maple stands in Ontario. For. Ecol. Manag. 2001, 148, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.F.; Curto, R.A.; Soares, C.P.B.; Piassi, L.C. Avaliação de métodos de medição de altura em florestas naturais. Rev. Árvore 2012, 36, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.B.D.; Morais, V.A.; Caetano, M.G.; Bernardes, L.F.G.M. Equações para estimativa volumétrica de espécies arbóreas da Amazônia. Rev. De Ciências Agroambientais 2020, 18, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, I.C.O.; Garlet, J.; Morais, V.A.; Araújo, E.J.G.; Silva, J.R.O.; Curto, R.A. Equations and form factor by species increase the precision and accuracy for estimating tree volume in the Amazon. Floresta 2022, 52, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutishauser, E.; Noor’an, F.; Laumonier, Y.; Halperin, J.; Rufi’ie, H.K.; Verchot, L. Generic allometric models including height best estimate forest biomass and carbon stocks in Indonesia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 307, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, F.M.B.; Jacovine, L.A.G.; Ribeiro, S.C.; Torres, C.M.M.E.; Silva, L.F.; Gaspar, R.O.; Rocha, S.J.S.S.; Staudhammer, C.L.; Fearnside, P.M. Allometric equations for volume, biomass and carbon in commercial stems harvested in a managed forest in the southwestern Amazon: A case study. Forests 2020, 11, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, R.A.; Silva, G.F.; Soares, C.P.B.; Martins, L.T.; David, H.C. Métodos de estimação de altura de árvores em Floresta Estacional Semidecidual. Floresta 2013, 45, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.C.; Mendonça, A.R.; Silva, G.F.; Curto, R.A.; Figueiredo, L.T.M.; Silva, M.L.M. Métodos de medição da altura comercial de árvores na região Amazônica. Sci. For. 2019, 47, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, K.M.A.; Silva-Ribeiro, R.B.; Gama, J.R.V.; Andrade, D.F.C. Eficiência na estimativa volumétrica de madeira na Floresta Nacional do Tapajós. Nativa 2018, 6, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, R.M.; Miguel, E.P.; Souza, H.J.; Souza, A.N.; Nascimento, R.G.M. Wood volume is overestimated in the Brazilian Amazon: Why not use generic volume prediction methods in tropical forest management? J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 350, 119593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutuoso, L.M.S.; Almeida, D.M.; Ucella-Filho, J.C.M.; Barbosa-Júnior, G.S.; Canto, J.L. Métodos de medição de altura em fragmento de Floresta Estacional Decidual. Nativa 2020, 8, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, R.A.; Loureiro, G.H.; Môra, R.; Miranda, R.O.V.; Péllico-Neto, S.; Silva, G.F. Relações hipsométricas em floresta estacional semidecidual. Rev. De Ciências Agrárias 2014, 57, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, S.A.; Figueiredo-Filho, A. Dendrometria. Curitiba; Universidade Federal do Paraná: Curitiba, Brazil, 2003; p. 309. [Google Scholar]

- Scolforo, J.R. Biometria Florestal, 1st ed.; UFLA: Lavras, Brazil, 2006; p. 352. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, X.M.; Mayrinck, R.C.; Silva, G.C.C.; Ferraz-Filho, A.C.; Mello, J.M. Modelo de estimativa de volume e carbono por hectare para fragmentos de cerrado sensu stricto em Minas Gerais. Enciclopédia Biosf. 2016, 13, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcik, L.Z.; Ruiz, E.C.Z.; Mussio, C.F.; Garrett, A.T.A. Relações hipsométricas para altura comercial de Araucaria angustifolia (Bertol.) Kuntze em fragmentos de Floresta Ombrófila Mista no Paraná. Braz. J. Anim. Environ. Res. 2023, 6, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiramatsu, N.A. Equações de Volume Comercial para Espécies Nativas na Região do Vale do Jari, Amazônia Oriental. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil, 2008; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Ribeiro, R.B.; Gama, J.R.V.; Melo, L.O. Seccionamento para cubagem e escolha de equações de volume para a Floresta Nacional do Tapajós. Cerne 2014, 20, 605–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.P.; Vacek, Z.; Vacek, S. Nonlinear mixed-effects height–diameter model for mixed-species forests in the central part of the Czech Republic. J. For. Sci. 2016, 62, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Kutchartt, E.; Hernández, J.; Corvalán, P.; Promis, A.; Zwanzig, M. Determination of optimal tree height models and calibration designs for Araucaria araucana and Nothofagus pumilio in mixed stands affected to different levels by anthropogenic disturbance in South-Central Chile. Ann. For. Sci. 2023, 80, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teshome, M.; Braz, E.M.; Torres, C.M.M.E.; Raptis, D.I.; Mattos, P.P.; Temesgen, H.; Rubio-Camacho, E.A.; Sileshi, G.W. Mixed-effects height prediction model for Juniperus procera trees from a dry Afromontane forest in Ethiopia. Forests 2024, 15, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçal, M.F.M.; Souza, Z.M.; Tavares, R.L.M.; Farhate, C.V.V.; Oliveira, S.R.M.; Galindo, F.S. Predictive models to estimate carbon stocks in agroforestry systems. Forests 2021, 12, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, E.S.; Souza, Z.M.; Oliveira, S.R.M.; Montanari, R.; Farhate, C.V.V. Random forest model to predict the height of Eucalyptus. Eng. Agrícola 2022, 42, e20210153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepstad, D.C.; de Carvalho, C.R.; Davidson, E.A.; Jipp, P.H.; Lefebvre, P.A.; Negreiros, G.H.; da Silva, E.D.; Stone, T.A.; Trumbore, S.E.; Vieira, S. The role of deep roots in the hydrological and carbon cycles of Amazonian forests and pastures. Nature 1994, 372, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.; Lennox, G.D.; Ferreira, J.; Berenguer, E.; Lees, A.C.; Mac Nally, R.; Thomson, J.R.; Ferraz, S.F.D.B.; Louzada, J.; Oliveira, V.H.F.; et al. Anthropogenic disturbance in tropical forests can double biodiversity loss from deforestation. Nature 2016, 535, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio). Plano de Manejo da Floresta Nacional do Tapajós—Volume I: Diagnóstico, 1st ed.; Ministério do Meio Ambiente: Brasília, Brazil, 2019; p. 316. [Google Scholar]

- Martorano, L.G.; Pereira, L.C.; Cesar, E.G.M.; Pereira, I.C.B. Estudos Climáticos do Estado do Pará, Classificação Climática (Köppen) e Deficiência Hídrica (Thornthwaite, Mather); SUDAM; Embrapa-SNLCS: Belém, PA, Brazil, 1993; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Martorano, L.G.; Brienza-Júnior, S.; Lisboa, L.S.S.; Moraes, J.R.S.; Aparecido, L.E.O.; Dias, C.T.S. A methodological proposal for topoclimatic zoning of native forest species in the Brazilian Amazon. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2025, 156, 156–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorano, L.G.; Soares, W.B.; Moraes, J.R.S.C.; Nascimento, W.; Aparecido, L.E.O.; Villa, P.M. Climatology of air temperature in Belterra: Thermal regulation ecosystem services provided by the Tapajós National Forest in the Amazon. Rev. Bras. De Meteorol. 2021, 36, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Manual Técnico da Vegetação Brasileira, 2nd ed.; Ministério do Planejamento, Orçamento e Gestão: Brasília, Brazil, 2012; p. 272. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, D.F.C.; Braga, C.R.; Silva, J.R.; Chaves, A.R.S. Do mil ao milhão: Estudo de caso do manejo florestal comunitário na Floresta Nacional do Tapajós. Biodiversidade Bras. 2022, 12, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, P.; Pinto, A.; Brito, B.; Hayashi, S. Quem é o dono da Amazônia? Uma Análise do Desmatamento e da Ocupação em Terras Públicas e Privadas na Região Amazônica; IMAZON: Belém, PA, Brazil, 2016; p. 108. [Google Scholar]

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2002, 2, 18–22. Available online: https://journal.r-project.org/articles/RN-2002-022 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- Vismara, E.S. Avaliação da Construção e Aplicação de Modelos Florestais de Efeitos Fixos e Efeitos Mistos sob o Ponto de Vista Preditivo. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, Piracicaba, Brazil, 2013; p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Lu, D.; Keller, M.; dos-Santos, M.N.; Bolfe, E.L.; Feng, Y.; Wang, C. Modeling and Mapping Agroforestry Aboveground Biomass in the Brazilian Amazon Using Airborne Lidar Data. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lussetti, D.; Kuljus, K.; Ranneby, B.; Ilstedt, U.; Falck, J.; Karlsson, A. Using linear mixed models to evaluate stand level growth rates for dipterocarps and Macaranga species following two selective logging methods in Sabah, Borneo. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 437, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cosmo, L.; Giuliani, D.; Dickson, M.M.; Gasparini, P. An individual-tree linear mixed-effects model for predicting the basal area increment of major forest species in Southern Europe. For. Syst. 2020, 29, e019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réjou-Méchain, M.; Flores, O.; Bourland, N.; Doucet, J.L.; Fétéké, R.F.; Pasquier, A.; Hardy, O.J. Spatial aggregation of tropical trees at multiple spatial scales. J. Ecol. 2011, 99, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerikäinen, K. A multivariate linear mixed-effects model for the generalization of sample tree heights and crown ratios in the Finnish National Forest Inventory. For. Sci. 2009, 55, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vibrans, A.C.; Moser, P.; Oliveira, L.Z.; Maçaneiro, J.P. Height-Diameter models for three subtropical forest types in Southern Brazil. Ciênc. Agrotec. 2015, 39, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Lei, X.; Sharma, R.P.; Li, H.; Zhu, G.; Hong, L.; You, L.; Duan, G.; Lei, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Comparing height-age and height-diameter modelling approaches for estimating site productivity of natural uneven-aged forests. Forestry 2018, 91, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.Y.; Lam, T.Y. Modelling height–diameter relationship of fifteen tree species planted on reclaimed agricultural lands with random species effects. Trop. For. 2022, 1053, e012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, M.; Favarin, J.A.S.; Marchesan, J.; Alba, E.; Berra, E.F.; Pereira, R.S. Machine learning and generalized linear model techniques to predict aboveground biomass in Amazon rainforest using LiDAR data. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2020, 14, 034518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Zhao, C. Enhanced Random Forest with concurrent analysis of static and dynamic nodes for industrial fault classification. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 16, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesan, J.; Alba, E.; Schuh, M.S.; Favarin, J.A.S.; Pereira, R.S. Aboveground biomass estimation in a tropical forest with selective logging using Random Forest and LiDAR data. Floresta 2020, 50, 1873–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, D.R.; Edwards, T.C.; Beard, K.H.; Cutler, A.; Hess, K.T.; Gibson, J.; Lawler, J.J. Random forests for classification in ecology. Ecology 2007, 88, 2783–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biau, G.; Scornet, E. A random forest guided tour. Test 2016, 25, 197–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, S.M.; Glaum, P.; Valdovinos, F.S. Interpreting random forest analysis of ecological models to move from prediction to explanation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, R.L.M.; Oliveira, S.R.M.; Barros, F.M.M.; Farhate, C.V.V.; Souza, Z.M.; Scala-Junior, N.L. Prediction of soil CO2 flux in sugarcane management systems using the random forest approach. Sci. Agric. 2018, 75, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babanezhad, M. Different Algorithms in Mixed Effect Models Estimation Approach. J. Appl. Math. Bioinform. 2012, 2, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, E.N.; Barbosa, B.H.G.; Silva, S.H.G.; Monti, C.A.U.; Tng, D.Y.P.; Gomide, L.R. Variable selection for estimating individual tree height using genetic algorithm and random forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 504, 119828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schielzeth, H. Simple Means to Improve the Interpretability of Regression Coefficients. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A. Scaling Regression Inputs by Dividing by Two Standard Deviations. Stat. Med. 2008, 27, 2865–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, X.A.; Donaldson, L.; Correa-Cano, M.E.; Evans, J.; Fisher, D.N.; Goodwin, C.E.D.; Robinson, B.S.; Hodgson, D.J.; Inger, R. A Brief Introduction to Mixed Effects Modelling and Multi-Model Inference in Ecology. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistics | Linear Mixed-Effects Model | Random Forest |

|---|---|---|

| 0.77 | 0.73 | |

| RMSE | 2.95 | 3.10 |

| MAE | 2.33 | 2.44 |

| MPD% | −2.62 | −2.76 |

| BIAS | 0.002 | −0.05 |

| Type of Effect | Group or Variable | Parameter or Levels | Estimate | Standard Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effect | Intercept | 11.196970 | 1.7269491 | |

| DBH | 0.142190 | 0.0328839 | ||

| DBH2 | −0.000499 | 0.0001653 |

| Random Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Representation | b0 (Rand. Intercept) | b1 (Rand. Slope) | (β0 + b0ⱼ) | (β1 + b1ⱼ) |

| Alexa grandiflora Ducke | Ag | −1.5227 | −0.0127 | 9.6743 | 0.1295 |

| Astronium lecointei Ducke | Al | 2.7863 | 0.0062 | 13.9832 | 0.1484 |

| Apuleia moralis Spruce ex Benth. | Am | −3.3846 | 0.0134 | 7.8124 | 0.1556 |

| Brosimum acutifolium Huber | Ba | −0.8260 | 0.0086 | 10.3709 | 0.1508 |

| Bagassa guianensis Aubl. | Bg | 2.0093 | −0.0452 | 13.2063 | 0.0970 |

| Buchenavia huberi Ducke | Bh | −1.6343 | −0.0034 | 9.5627 | 0.1388 |

| Cedrelinga catenaeformis Ducke | Cc | 4.6445 | −0.0260 | 15.8414 | 0.1162 |

| Couratari guianensis Aubl. | Cg | 5.1793 | −0.0180 | 16.3763 | 0.1242 |

| Cedrela odorata L. | Co | −1.2278 | 0.0043 | 9.9692 | 0.1465 |

| Diplotropis purpurea (Rich.) Amshoff | Dp | 1.1351 | −0.0081 | 12.3321 | 0.1340 |

| Hymenaea courbaril L. | Hc | 6.7646 | −0.0044 | 17.9616 | 0.1378 |

| Hymenolobium petraeum Ducke | Hp | −1.2825 | 0.0010 | 9.9145 | 0.1432 |

| Hymenaea parvifolia Huber | Hpa | 2.8247 | −0.0028 | 14.0216 | 0.1394 |

| Handroanthus serratifolius (Vahl) Nichols. | Hs | 1.8504 | 0.0106 | 13.0473 | 0.1528 |

| Lecythis lurida (Miers) S.A. Mori | Ll | −1.5838 | 0.0158 | 9.6132 | 0.1580 |

| Lecythis pisonis Cambess. | Lp | −6.0406 | 0.0235 | 5.1564 | 0.1656 |

| Manilkara huberi (Ducke) Chevalier | Mh | −2.2909 | 0.0280 | 8.9061 | 0.1702 |

| Mezilaurus itauba (Meisn.) Taub. ex Mez | Mi | −0.8588 | 0.0216 | 10.3381 | 0.1638 |

| (conclusion) Ocotea baturitensis Vattimo | Ob | 3.3957 | −0.0149 | 14.5927 | 0.1272 |

| Parkia multijuga Benth. | Pm | −1.0481 | 0.0057 | 10.1488 | 0.1479 |

| Pseudopiptadenia psilostachya (Benth.) G.P. Lewis & L. Rico | Pp | −4.3135 | −0.0076 | 6.8834 | 0.1346 |

| Schizolobium amazonicum Huber ex Ducke | Sam | 0.9222 | 0.0030 | 12.1192 | 0.1452 |

| Swartzia laurifolia Benth. | Sl | −0.5173 | 0.0075 | 10.6797 | 0.1497 |

| Trattinnickia rhoifolia Willd. | Tr | 0.3874 | −0.0256 | 11.5844 | 0.1166 |

| Vochysia maxima Ducke | Vm | −5.5428 | 0.00063 | 5.6542 | 0.1428 |

| Vatairea paraensis Ducke | Vp | 0.1743 | 0.0190 | 11.3713 | 0.1612 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, R.B.d.S.; Reis, L.P.; Woycikievicz, A.P.F.; Mello, M.N.d.; Oliveira, A.H.M.; Dias, C.T.d.S.; Martorano, L.G. Modeling Commercial Height in Amazonian Forests: Accuracy of Mixed-Effects Regression Versus Random Forest. Forests 2026, 17, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010030

Ribeiro RBdS, Reis LP, Woycikievicz APF, Mello MNd, Oliveira AHM, Dias CTdS, Martorano LG. Modeling Commercial Height in Amazonian Forests: Accuracy of Mixed-Effects Regression Versus Random Forest. Forests. 2026; 17(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Renato Bezerra da Silva, Leonardo Pequeno Reis, Antonio Pedro Fragoso Woycikievicz, Marcello Neiva de Mello, Afonso Henrique Moraes Oliveira, Carlos Tadeu dos Santos Dias, and Lucietta Guerreiro Martorano. 2026. "Modeling Commercial Height in Amazonian Forests: Accuracy of Mixed-Effects Regression Versus Random Forest" Forests 17, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010030

APA StyleRibeiro, R. B. d. S., Reis, L. P., Woycikievicz, A. P. F., Mello, M. N. d., Oliveira, A. H. M., Dias, C. T. d. S., & Martorano, L. G. (2026). Modeling Commercial Height in Amazonian Forests: Accuracy of Mixed-Effects Regression Versus Random Forest. Forests, 17(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010030