3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

Efforts were made to ensure gender representation when selecting participants for the survey. However, male respondents made up a higher proportion of the sample, largely reflecting their direct involvement in forest management and conservation activities in the studied communities. Of the 412 individuals surveyed, 302 (73%) were male, while 110 (27%) were female (

Figure 3).

Figure 3 shows as the respondents were grouped into five age categories: 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55 years and above. Eligibility for participation required individuals to be at least 18 years old. Based on the data collected, 4% of respondents answered between 18 and 24 years, 18% between 25 and 34, 48% between 35 and 34, 20% between 45 and 54, and 8% above 55.

In terms of educational attainment, 47% of respondents had completed primary education. A substantial proportion of the participants were illiterate, reflecting ongoing barriers to educational access in rural agricultural communities. The number of respondents with higher education, college, or university level was relatively low, underscoring the limited availability of tertiary education in the study areas. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that those with higher educational qualifications are likely to be younger individuals, possibly the children of farmers, who have had increased access to educational opportunities in recent years.

3.2. Local Community Interest in Conservation

3.2.1. Community Participation and Awareness in Forest Conservation

There was a notable disparity in the level of biodiversity conservation and control between the three locations (X

2 = 11.81, df = 4,

p < 0.019). This encompasses an understanding of conservation laws and policies as well as the active involvement of local communities in the restoration and establishment of habitats. The frequency distribution reveals that the response “somewhat high” has the highest proportion (25% to 40%) among all locations.

Table 1 below shows local conservation participation in the Dangila, Fagita, and Banja districts. Engagement levels included medium, high, somewhat high, very high, and extremely high. In “medium,” Dangila is 24, Fagita 28, and Banja 16. Three values make up 17% of the total. These data show medium involvement, with Fagita marginally ahead. The 16% “high” involvement frequencies are 22 in Dangila, 26 in Fagita, and 17 in Banja. This implies a high level of participation, particularly in Fagita.

Dangila, Fagita, and Banja have 36, 38, and 28 “somewhat high” cases, making up 25% of the total. This implies significant engagement with Fagita leading. Dangila, Fagita, and Banja are “very high” with 30, 36, and 21 frequencies. These three regions account for 21% of the total, suggesting community involvement, particularly in Fagita. Dangila and Fagita, which had “extremely high” participation frequencies of 30 and 39. Banja, with 21 frequencies, contributed 22%, indicating the greatest interaction.

Fagita has the highest engagement rate at 40.5%. Dangila follows at 34.5%, while Banja is behind, at 25%. This shows that Fagita has the most proactive involvement in the conservation community. The chi-square test shows a significant difference in community involvement between districts (X2 = 11.81*, df = 4, p = 0.019). However, this divergence is unlikely to be random. Fagita shows substantial community involvement in conservation efforts with consistently high frequencies in all interaction areas. Banja is least involved, followed by Dangila. Policy makers and stakeholders need this information to understand community engagement and to design conservation actions to increase participation, particularly in low-engagement regions.

3.2.2. Level of Local Community Awareness and Adherence to Conservation Laws and Policies

Table 2 examines the level of local community awareness and adherence to conservation laws and policies in three districts: Dangila, Fagita, and Banja. The knowledge categories were classified as medium, high, very high, and extremely high. In the category “Somewhat medium,” Dangila had a frequency of 23, Fagita had a frequency of 27, and Banja had a frequency of 17. These frequencies collectively account for 16% of the total. This indicates a medium level of community awareness, with Fagita demonstrating slightly higher knowledge. The “High” group displays frequencies of 24 in Dangila, 27 in Fagita, and 16 in Banja, accounting for 16% of the total. This signifies a significant level of comprehension, with Fagita being somewhat higher than the others.

In the category “Somewhat high,” Dangila had a total of 37, Fagita 45, and Banja 25. Together, these numbers make up 26% of the total, indicating a notable level of community knowledge, particularly in Fagita. Dangila has a knowledge level classified as “Very high” with a score of 29, Fagita has a score of 35, and Banja has a score of 21. These scores accounted for 21% of the total and indicated a significant level of understanding, particularly in Fagita. The “Extremely high” category exhibits frequencies of 29 in Dangila, 33 in Fagita, and 24 in Banja, constituting 21% of the overall total. This category signifies the highest level of community comprehension, with Fagita taking the lead, followed by Dangila.

Fagita had the highest percentage of knowledge at (40.5%), followed by Dangila at (34.5%) and Banja at (25%). This suggests that Fagita has the most knowledgeable community regarding conservation laws and policies. The chi-square test results (X2 = 13.3*, df = 4, p = 0.01) demonstrated a statistically significant disparity in community knowledge levels among districts. This suggests that the observed differences are meaningful and are not the result of random chance.

In conclusion, the analysis demonstrated that Fagita possessed the greatest level of local community knowledge for effectively navigating and adhering to conservation laws and policies, followed by Dangila and Banja. Fagita regularly exhibited greater frequencies across all knowledge areas, demonstrating strong and comprehensive community comprehension. The obtained chi-square value was highly significant, indicating that the observed differences were statistically significant. This finding offers vital information for policy makers and stakeholders to customize teaching and enforcement initiatives to improve compliance, particularly in districts with lower levels of knowledge.

3.2.3. Respecting Local By-Laws

There was a strong variation (X2 = 314.6* df = 3, p = 0.00 between categories for local communities’ engagement and respect for local by-laws of CBFM. Most respondents (70.8%) agreed that users and non-users of the CBFM projects were willing to obey rules regarding responsibilities, benefits, and revenues. Local communities were highly engaged (91.7%) in respecting local by-laws for conservation and management, and most of the user groups of CBFM (70.8%) showed respect for forest and local administration boundaries to reduce conflicts between interested groups.

3.2.4. Local Community Involvement in Habitat Restoration and Creation

Table 3 shows the involvement of the local community in habitat restoration and creation in Dangila, Fagita, and Banja. The engagement levels are very low, low, medium, high, and very high. Dangila has nine “very low” engagements, Fagita three, and Banja two. This is only 3% of the total. This suggests that low involvement is rare, with Dangila having the highest incidence but still showing mild interest. There are even fewer “low” involvement cases, with three in Dangila, one in Fagita, and one in Banja, totaling 1%. This shows that low participation is rare in all the districts.

Table 4 shows Dangila, Fagita, and Banja have 23, 26, and 19 frequencies, respectively, making up 17% of “medium” engagements. This implies moderate community engagement, with Fagita leading. About 40% of the total—52 incidents in Dangila, 68 in Fagita, and 44 in Banja—are “high” engagement. This finding suggests substantial community involvement, notably in Fagita, which has the highest frequency. Dangila has 52 “very high” engagements, Fagita 69, and Banja 40, accounting for 39% of the total. These statistics show considerable engagement, with Fagita and Dangila leading the way.

With 40.5% engagement, Fagita is the most involved. Banja has the lowest engagement rate at 25%, followed by Dangila at 34.5%. Fagita has the greatest community involvement in habitat restoration and creation. The chi-squared test (X2 = 301*, df = 4, p = 0.000) shows a statistically significant variation in community engagement throughout the districts, suggesting that the changes are not random.

Research has shown that Fagita has the most local community involvement in restoring and creating new habitats, followed by Dangila and Banja. Fagita has a higher frequency in all the important interaction categories, indicating considerable community involvement in habitat improvement. The observed differences are statistically significant according to the chi-square test. These data are essential for policy makers and stakeholders if they are to understand community involvement and to develop strategies to increase it, particularly in low-engagement regions.

3.3. Results Regarding Socioeconomic Interest in CBFM

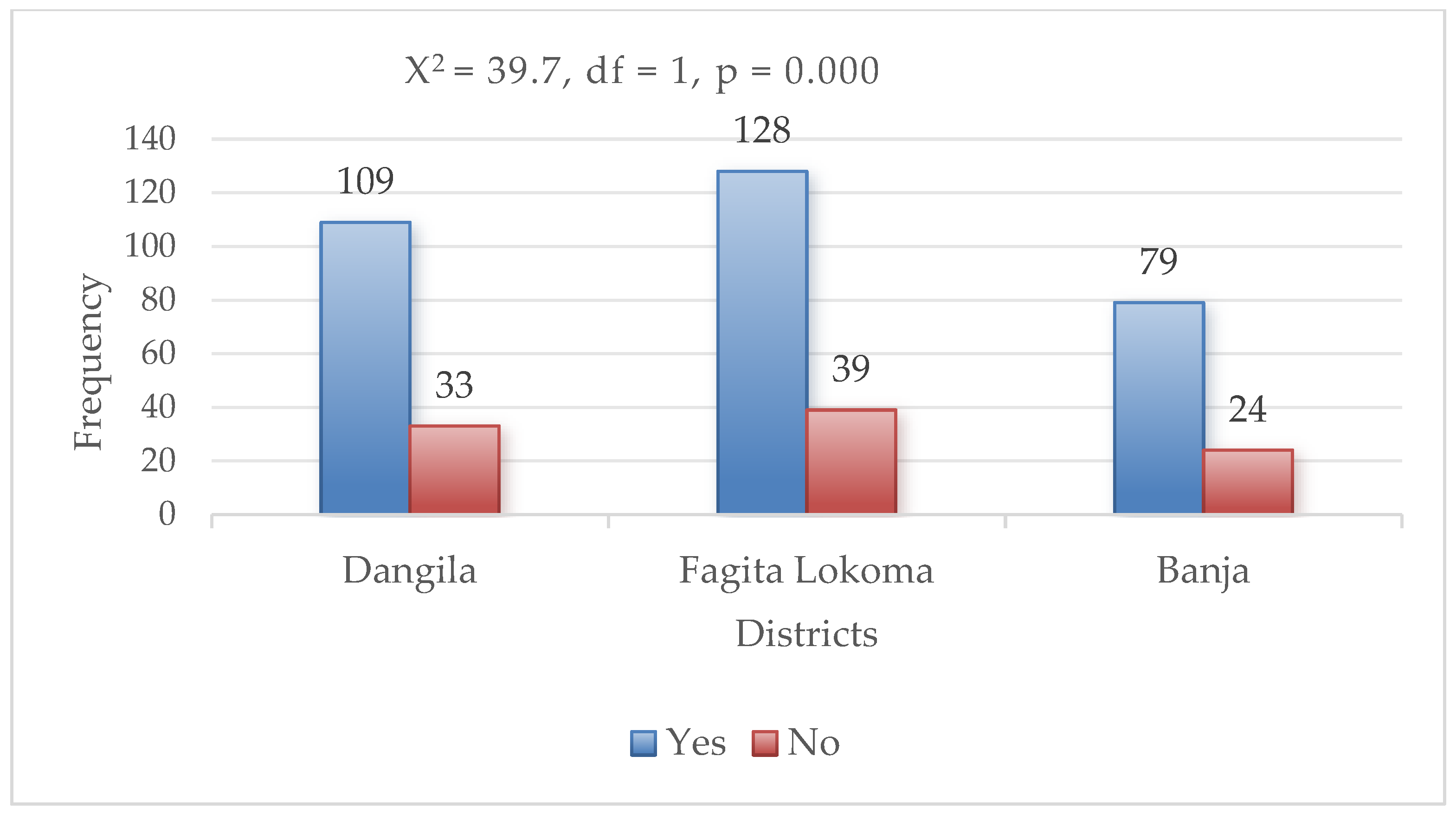

There is a significant difference (with a chi-square value of (X

2= 39.7*, df = 1,

p = 0.000) in frequency between “Yes” and “No” across the three districts. Most respondents (76.7%) agreed that the local communities have social and economic interest in natural resource conservation (

Figure 4). This interest significantly affects decision making regarding participation and engagement in initiatives to conserve natural resources.

This high level of agreement suggests that these interests significantly influence the decision-making processes related to participation and engagement in conservation initiatives.

- (A)

Economic benefits of selling wildlife for the ecosystem

Table 5 displays statistics regarding the perceived economic advantage derived by ecosystems from the sale of wildlife in three districts: Dangila, Fagita–Lokoma, and Banja. The responses were classified into five categories of significance: not significant, low-significance, medium-significance, significant, and high-significance.

In Dangila, among the 142 respondents, 16 individuals (11%) perceived the economic gain as not significant, 55 individuals (38%) evaluated it as low-significance, 46 individuals (30%) viewed it as moderately significant, 8 individuals (8%) found it significant, and 17 individuals (13%) considered it highly significant. The distribution of responses indicates that there is a prevailing impression of relatively low-to-moderate importance when it comes to the economic advantages of selling wildlife. Out of the 167 respondents in Fagita–Lokoma, 18 individuals (11%) perceived the economic gain as not significant, 67 individuals (38%) assessed it as low-significance, 49 individuals (30%) viewed it as medium-significance, 10 individuals (8%) considered it significant, and 23 individuals (13%) believed it is highly significant. In Fagita–Lokoma, as in Dangila, most people considered the advantages of low-to-medium importance. However, there was a somewhat larger group of respondents who viewed benefits as highly important. In Banja, out of a total of 103 responses, 13 individuals (11%) perceived the advantage as not insignificant, 33 individuals (38%) rated it as low significance, 30 individuals (30%) viewed it as medium significance, 15 individuals (8%) found it substantial, and 12 individuals (13%) considered it highly significant. The pattern observed in Banja aligns with that observed in other districts, indicating a prevailing perspective of low-to-medium relevance. However, a greater proportion of respondents in Banja considered it to be significant than those in Dangila and Fagita–Lokoma. In general, the data indicates that in all three districts, the economic advantage of ecosystems derived from wildlife sales is mostly considered to be of low-to-medium significance. The chi-square statistics (X2 = 142*, df = 4, p = 0.000) demonstrate a substantial and statistically significant disparity in perceptions among these districts, highlighting different levels of economic assessment and the potential impact on local economic policies related to wildlife sales.

- (B)

Food from wildlife contributes to food discounts

The perceived contributions of wildlife to food discounts in Dangila, Fagita–Lokoma, and Banja are shown in

Table 6. Responses were rated as not significant, low-significance, medium-significance, substantial, or extremely significant. In Dangila, out of 142 respondents, 7 (8%) considered wildlife’s contribution to food discounts as insignificant, 12 (16%) low, 72 (45%) medium, 33 (17%) significant, and 18 (13%) highly significant. Most Dangila respondents assessed wildlife’s contribution to food discounts as medium. Of the 167 replies in Fagita–Lokoma, 12 (8%) rated the contribution as not insignificant, 30 (16%) as low-significance, 76 (45%) as medium-significance, 25 (17%) as substantial, and 24 (13%) as highly significant. Similar to Dangila, most Fagita–Lokoma respondents reported medium significance. In Banja, 15 (8%) of 103 respondents deemed the contribution not significant, 25 (16%) low-significance, 39 (45%) medium-significance, 12 (17%) substantial, and 12 (13%) highly significant. Banja viewed it as having medium importance, similar to the other two districts. Most respondents in all three districts viewed wildlife’s contribution to food discounts as of medium significance. On average, 45% of respondents in each district chose medium significance. The chi-square result (X

2 = 175.7*, df = 4,

p = 0.000) shows that districts regard wildlife’s contribution to food discounts differently. This heterogeneity implies that while medium significance is a widespread view, low, substantial, and extremely significant assessments vary, which can influence district-specific interventions (

Table 5).

- (C)

Economic benefit generated from timber

Table 7 below displays the anticipated economic advantages of the ecosystems resulting from timber production in Dangila, Fagita–Lokoma, and Banja. Responses were classified into four categories based on their significance levels: low, medium, substantial, and highly significant. Among the 142 participants in Dangila, 2% perceived the advantage as insignificantly low, 13% considered it somewhat significant, 55% considered it substantial, and 31% regarded it as highly important. Among the 167 respondents in Fagita–Lokoma, 2% considered it to have low significance, 13% considered it to have medium relevance, 55% considered it to have substantial significance, and 31% considered it to have highly significant significance. Among the 103 respondents in Banja, 2% perceived it as having low significance, 13% as having medium significance, 55% as having substantial significance, and 31% as having highly significant significance. Overall, most individuals in each district perceived the economic impact of timber as substantial or highly substantial. The chi-square statistics (X

2 = 261.5*, df = 3,

p = 0.000) demonstrated a considerable disparity in perceptions within the districts, emphasizing the universal acknowledgement of timber’s economic importance.

- (D)

Benefits from tourism for the economic ecosystem

As shown in

Table 8 below, low significance occurs only 6% of the time in Dangila, Fagita Lokoma, and Banja. The economic ecosystem appears to have had little impact on the tourism industry. Medium-significance features are more common, with 26% of Dangila, Fagita Lokoma, and Banja frequencies (at 35, 44, and 27). The tourism ecosystem benefits from these moderate factors. Significant features are much more common, with 44 in Dangila, 56 in Fagita Lokoma, and 33 in Banja, (32% of the total), indicating a major tourist attraction. Highly significant features are most common, with 56 in Dangila, 60 in Fagita Lokoma, and 34 in Banja (36%). These key elements make these locations popular as tourist destinations. According to the chi-square test (X

2 = 24*, df = 3,

p = 0.000), these characteristics vary significantly between regions, showing non-random variance. Dangila, Fagita Lokoma, and Banja have many tourism-boosting qualities. Fagita Lokoma is appealing because of its high prevalence in important areas. Tourism in Dangila and Banja is promising. This analysis will help stakeholders to promote and improve tourism in these areas.