Fire Danger Climatology Using the Hot–Dry–Windy Index: Case Studies from Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Event Selection

- Chamusca (2003)—Occurred during one of the most destructive fire seasons in recent Portuguese history, with over 425,000 ha burned nationally.

- Pedrógão Grande (2017)—A catastrophic June wildfire that caused 66 fatalities and rapid fire spread due to extreme weather conditions.

- Lousã/Coimbra (2017)—Part of the October 2017 firestorm, exacerbated by strong winds and dry fuels, burning over 200,000 ha in 24 h.

- Monchique (2018)—A prolonged fire in the Algarve region, fueled by persistent high temperatures and complex terrain.

- Covilhã (2022)—A major wildfire in central Portugal, occurring during an intense summer heatwave, affected protected natural areas.

| Wildfire Event Location of the Ignition | Ignition Day (Alert) | Extinction Day | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | Municipality | Parish | Location | Date/Hour | Date/Hour |

| Santarém | Chamusca | Ulme | Poldro | 2 August 2003, 11:20 | 7 August 2003, 20:00 |

| Leiria | Pedrógão Grande | Pedrógão Grande | Escalos Fundeiros | 17 June 2017, 14:43 | 22 June 2017, 09:22 |

| Coimbra | Lousã | Vilarinho | Prilhão, Vilarinho | 15 October 2017, 08:41 | 17 October 2017, 02:31 |

| Faro | Monchique | Monchique | Perna da Negra | 3 August 2018, 13:32 | 11 August 2018, 21:50 |

| Castelo Branco | Covilhã | Vila do Carvalho | Garrucho | 6 August 2022, 03:18 | 2 September 2022, 21:00 |

| Wildfire Event Designation | Fire Location 1 | Total Burnt Area (ha) | Type of Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chamusca | 39.35° N; 8.39° W | 22,190.00 | Natural (lightning) |

| Pedrógão Grande | 39.875° N; 8.125° W | 30,358.84 | Negligent |

| Lousã | 40.13° N; 8.21° W | 53,618.81 | Negligent |

| Monchique | 37.40° N; 8.59° W | 26,763.83 | Unknown |

| Covilhã | 40.31° N; 7.50° W | 24,333.24 | Intentional |

2.2. Meteorological Data

2.3. The Hot–Dry–Windy Index (HDW) and the Fire Weather Index (FWI)

- Initial Spread Index (ISI)—driven by wind and fine fuel moisture.

- Buildup Index (BUI)—reflects fuel availability and dryness.

- Fire Weather Index (FWI)—combines ISI and BUI into a single, dimensionless index representing fire intensity under open, level terrain.

2.4. Spearman Rank Correlation Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Chamusca Fire (2 August 2003)

3.2. The Pedrógão Grande Fire (17 June 2017)

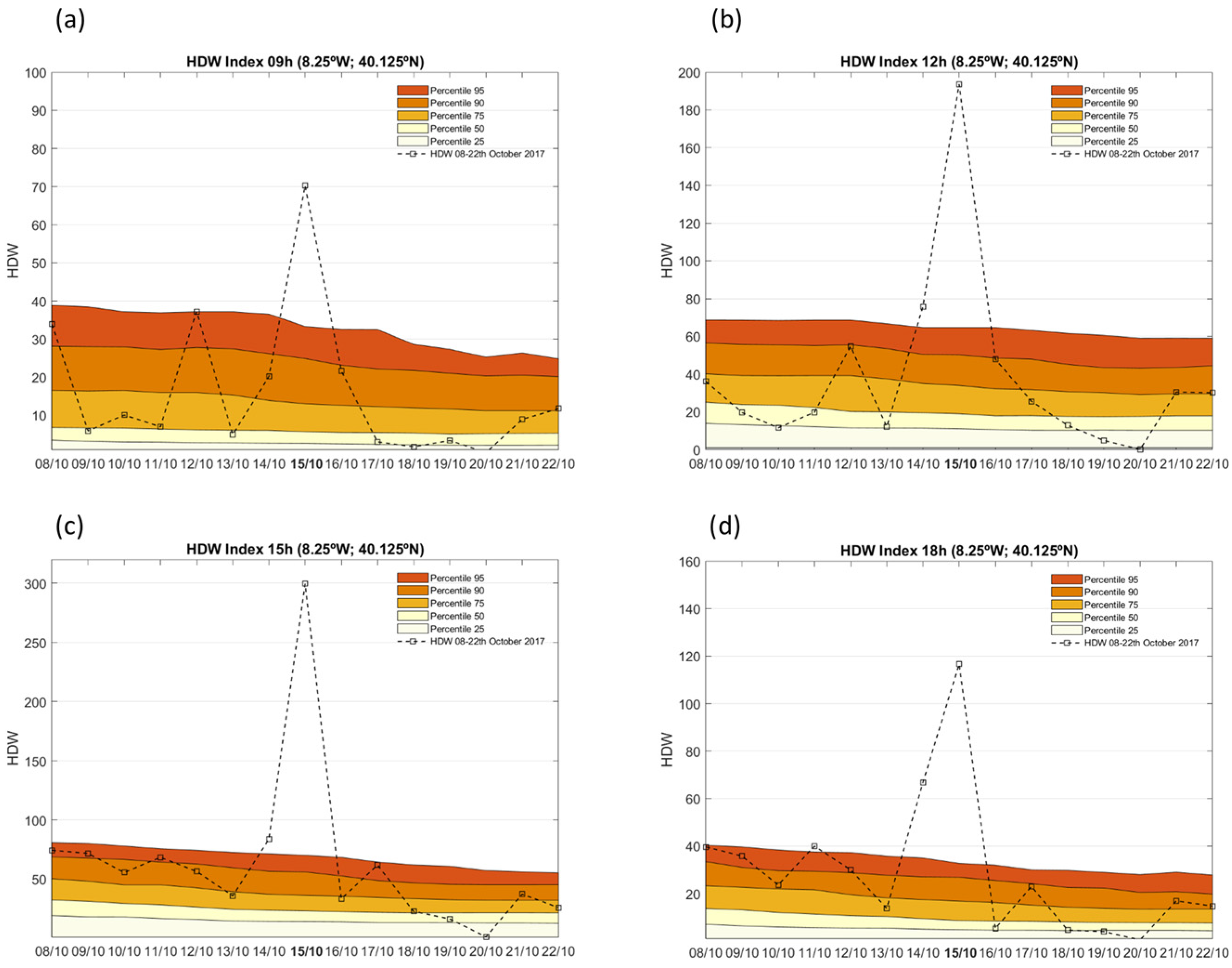

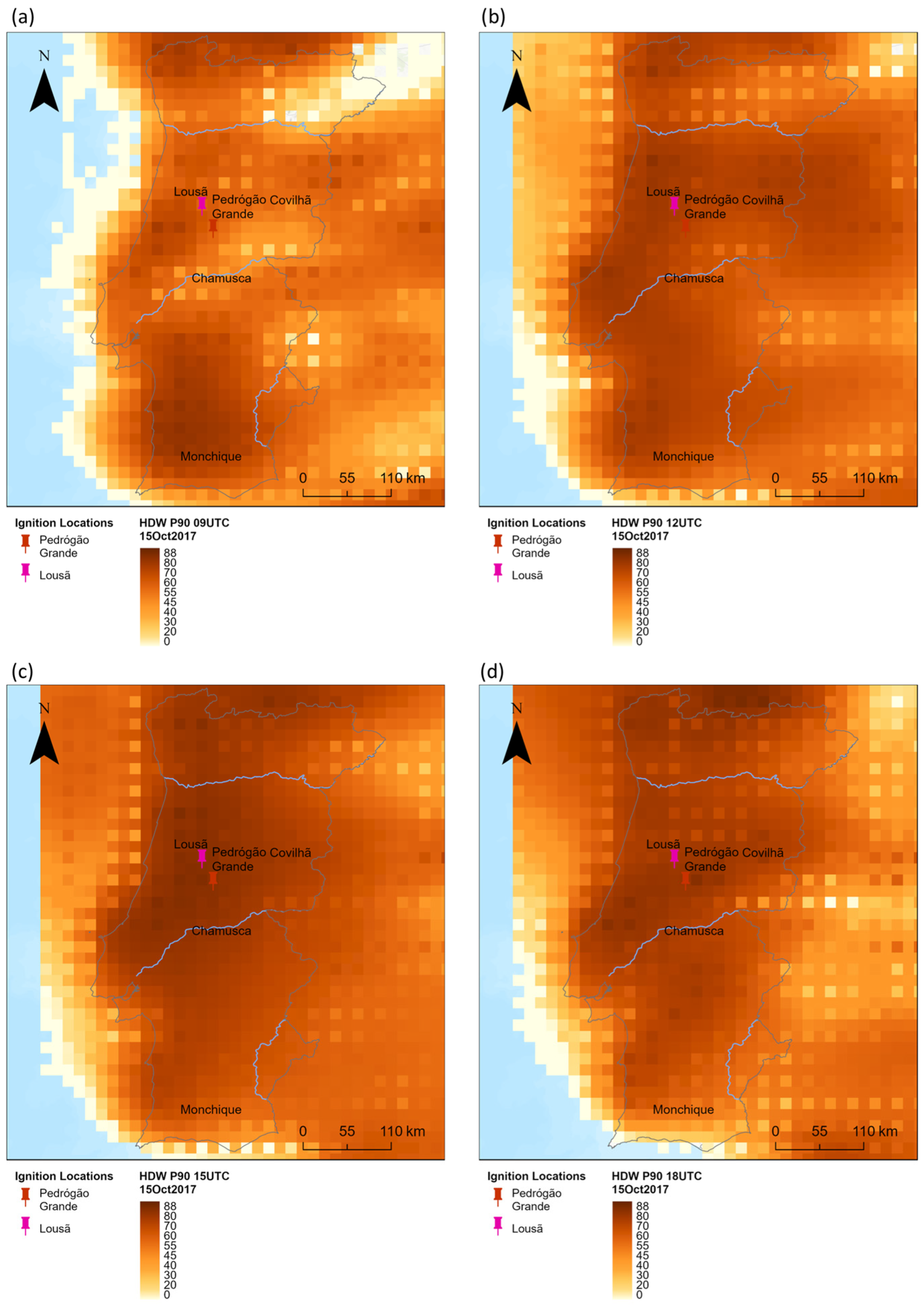

3.3. The Lousã Fire (15 October 2017)

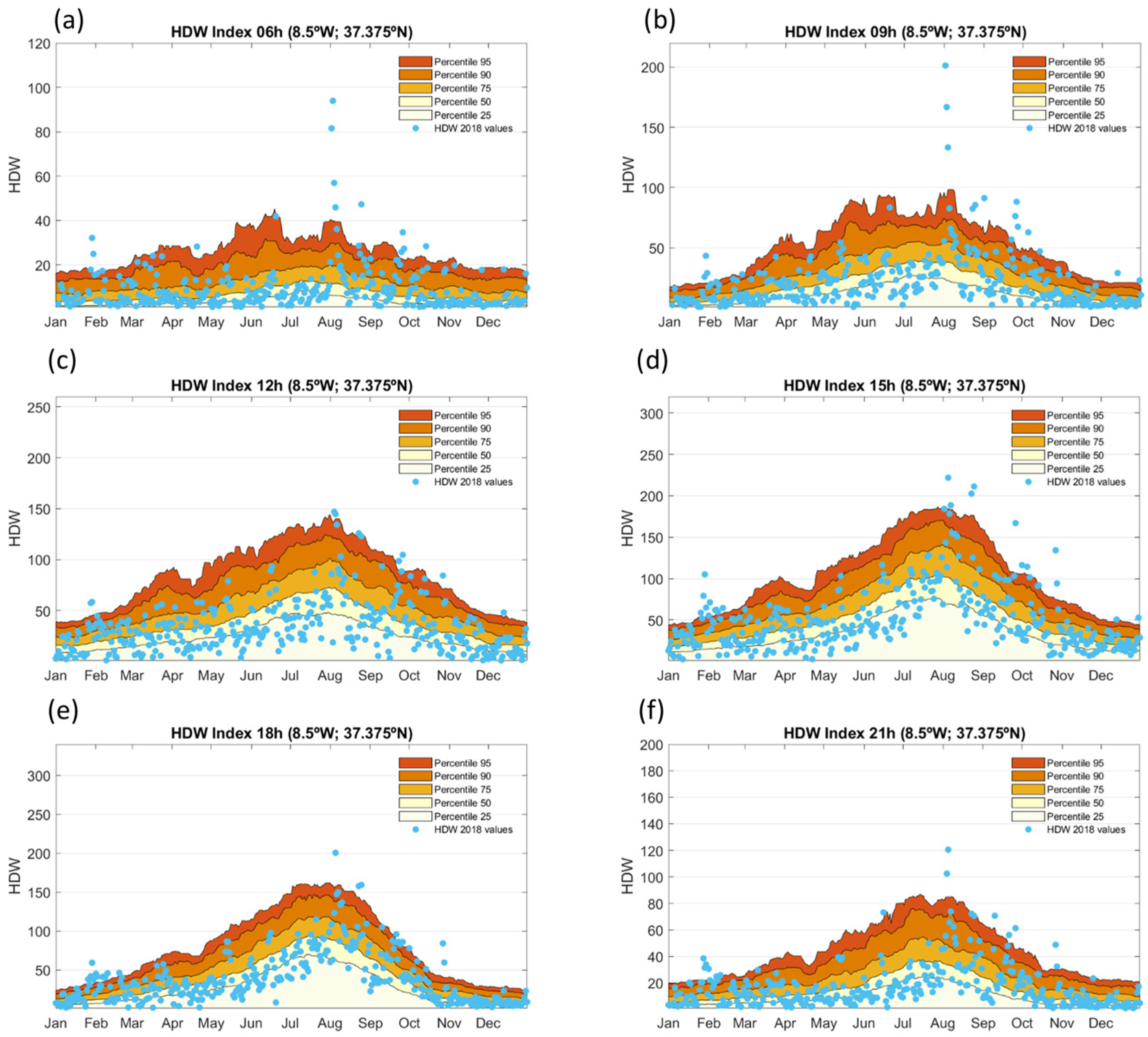

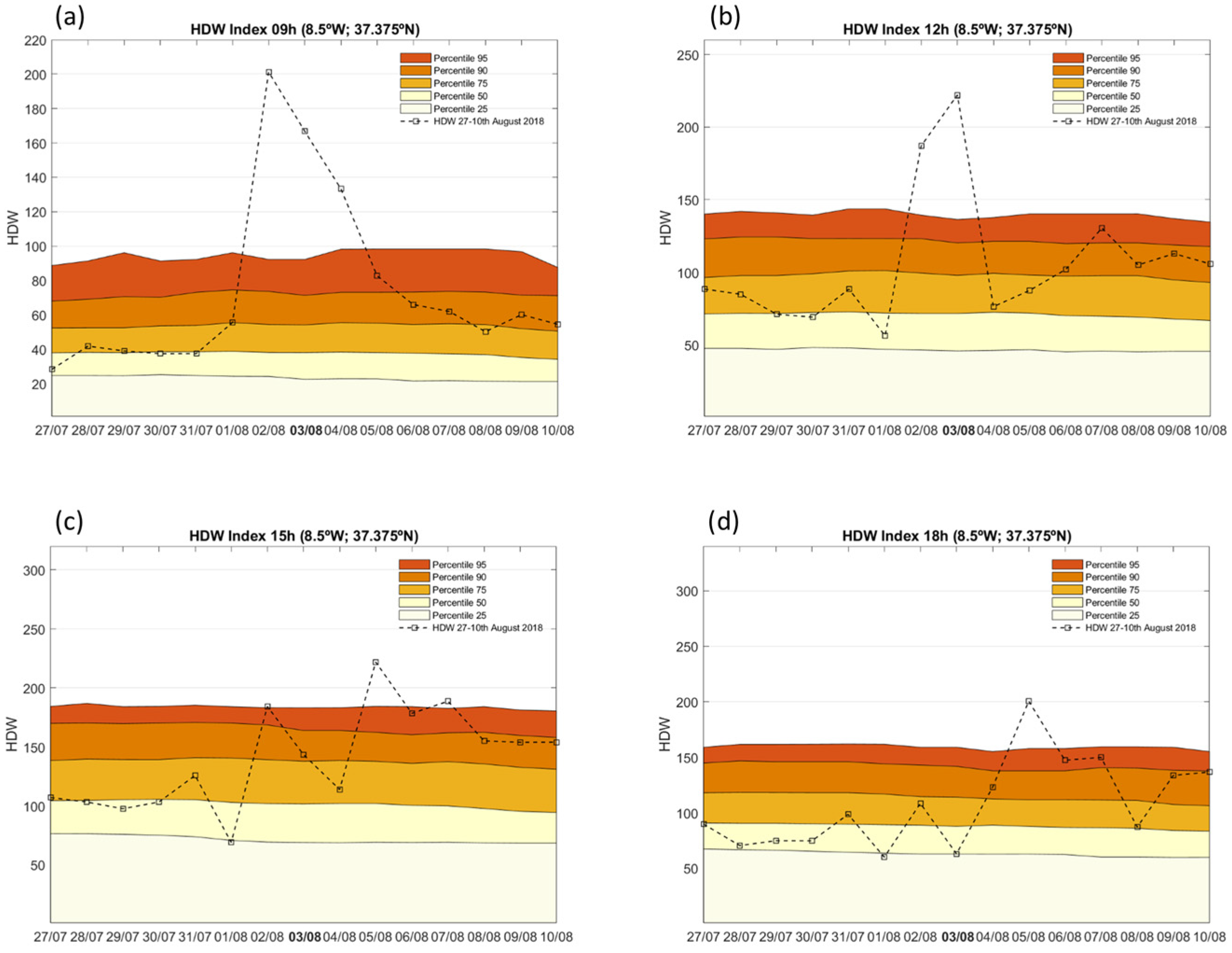

3.4. The Monchique Fire (3 August 2018)

3.5. The Covilhã (Serra da Estrela) Fire (6 August 2022)

3.6. Cross-Case Comparison

3.7. Comparison Between HDW and FWI for Major Wildfire Events

- Complementarity of HDW and FWI: While FWI captures fuel dryness and temperature effects, HDW provides a unique perspective on wind and vertical atmospheric structure, which are essential for forecasting erratic fire behaviour, especially in wind-driven scenarios. Their combined use can offer a more comprehensive situational awareness of fire danger.

- Divergences are informative: Events such as Lousã (2017) and Covilhã (2022) show how either index may fail in isolation: FWI can miss sudden wind-driven extremes, and HDW may not detect slow-onset heat/drought-driven risks. These divergences underscore the need for multi-indicator fire danger systems.

- Temporal persistence matters: Not only peak values but also the duration of exceedance is a critical indicator of fire potential. As shown in Table 5, persistent exceedances (e.g., Monchique, Covilhã) align with prolonged suppression challenges and large burn areas, emphasizing the importance of tracking multi-day danger windows.

4. Discussion

4.1. Temporal Dynamics and HDW Extremes

- For Pedrógão Grande (2017), a clear peak at 15 UTC (Figure 8c) exceeded 140 units (>P95), consistent with the timing of ignition and rapid initial spread. Notably, this period was also identified by Andrade and Bugalho [8] as one of the highest FWI days of the season, with values over 50 (considered very high) sustained across central Portugal.

- The Monchique (2018) event was preceded by a persistent HDW anomaly between 2 and 5 August, peaking above 200 units (Figure 14c), indicating prolonged heat stress and enhanced wind contribution.

- In Covilhã (2022), although less extreme than other cases, HDW surpassed the 75th percentile (Figure 17) during early afternoon hours (12–18 UTC), aligning with synoptic-scale dry air advection and elevated FWI, confirming a moderately high to very high fire danger level.

4.2. HDW vs. FWI: Complementary Indicators

4.3. Spatial Footprints and Synoptic Drivers

4.4. Operational Implications and Forecast Utility

5. Conclusions

- On the day of fire ignition, HDW values consistently peaked in the afternoon (12–18 UTC), which coincided with the most volatile phases for fire spread and highlighted the significance of sub-daily monitoring.

- HDW values consistently exceeded high climatological percentiles, illustrating the ability to identify compound extremes in wind, heat, and dryness—conditions that daily averaged indices frequently overlook.

- By emphasizing regional-scale atmospheric anomalies that strengthened local fire potential, the HDW index demonstrated strong spatial coherence with ignition zones.

- HDW consistently signalled high fire danger on ignition days across all events, often more clearly than FWI. When compared with the FWI, particularly for the 2017 fires (FWI underestimated fire risk in the June and October 2017 events, staying below critical thresholds despite extreme fire behaviour), HDW provided higher temporal sensitivity and greater responsiveness to dynamic weather events, reinforcing its value as a complementary tool to existing fire danger metrics.

- FWI is sensitive to fuel moisture dynamics, while HDW is driven by atmospheric forcing, making them complementary rather than redundant.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BUI | Buildup Index |

| CFFDRS | Canadian Forest Fire Danger Rating System |

| DTM | Digital Terrain Model |

| ECMWF | European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts |

| ERA5 | ECMWF Reanalysis v5 |

| ET0 | Reference Evapotranspiration |

| FWI | Fire Weather Index |

| HDW | Hot–Dry–Windy Index |

| IFS | Integrated Forecasting System |

| IPMA | Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera |

| ISI | Initial Spread Index |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| T | Temperature |

| U | Wind Speed |

| UTC | Coordinated Universal Time |

| VPD | Vapor Pressure Deficit |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

References

- Carvalho, A.; Flannigan, M.D.; Logan, K.A.; Miranda, A.I.; Borrego, C. Fire activity in Portugal and its relationship to weather and the Canadian Fire Weather Index System. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2008, 17, 328–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedia, J.; Herrera, S.; Camia, A.; Moreno, J.M.; Gutiérrez, J.M. Forest fire danger projections in the Mediterranean using ENSEMBLES regional climate change scenarios. Clim. Chang. 2014, 122, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffault, J.; Curt, T.; Moron, V.; Trigo, R.M.; Mouillot, F.; Koutsias, N.; Pimont, F.; Martin-StPaul, N.; Barbero, R.; Dupuy, J.-L.; et al. Increased Likelihood of Heat-Induced Large Wildfires in the Mediterranean Basin. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolly, W.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; Freeborn, P.H.; Holden, Z.A.; Brown, T.J.; Williamson, G.J.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. Climate-induced variations in global wildfire danger from 1979 to 2013. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffault, J.; Curt, T.; Martin-StPaul, N.; Moron, V.; Trigo, R.M. Extreme wildfire events are linked to global-change-type droughts in the northern Mediterranean. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, M.; Jerez, S.; Augusto, S.; Tarín-Carrasco, P.; Ratola, N.; Jiménez-Guerrero, P.; Trigo, R.M. Climate drivers of the 2017 devastating fires in Portugal. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Oom, D.; Artes, T.; Viegas, D.X.; Fernandes, P.; Faivre, N.; Freire, S.; Moore, P.; Rego, F.; Castellnou, M. Forest Fires in Portugal in 2017. In Science for Disaster Risk Management 2020: Acting Today, Protecting Tomorrow, EUR 30183 EN; Casajus Valles, A., Marin Ferrer, M., Poljanšek, K., Clark, I., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-18182-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C.; Bugalho, M.N. Multi-indices diagnosis of the conditions that have led to the two 2017 major wildfires in Portugal. Fire 2023, 6, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srock, A.F.; Charney, J.J.; Potter, B.E.; Goodrick, S.L. The Hot-Dry-Windy Index: A new fire weather index. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, J.M.; Srock, A.F.; Charney, J.J. Development and Application of a Hot-Dry-Windy Index (HDW) Climatology. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, K.G.; Flannigan, M.D.; Tymstra, C. Enhanced prediction of extreme fire weather conditions in spring using the Hot-Dry-Windy Index in Alberta, Canada. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2024, 33, WF24015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Sun, F. Changes in the severity of compound hot-dry-windy events over global land areas. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, J.L.; Fargeon, H.; Martin-StPaul, N.; Pimont, F.; Ruffault, J.; Guijarro, M.; Hernando, C.; Madrigal, J.; Fernandes, P. Climate change impact on future wildfire danger and activity in southern Europe: A review. Ann. For. Sci. 2020, 77, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedia, J.; Herrera, S.; Martín, D.S.; Koutsias, N.; Gutiérrez, J.M. Robust Projections of Fire Weather Index in the Mediterranean Using Statistical Downscaling. Clim. Chang. 2013, 120, 229–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hantson, S.; Hamilton, D.S.; Burton, C. Changing fire regimes: Ecosystem impacts in a shifting climate. One Earth 2024, 7, 942–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICNF. Available online: https://fogos.icnf.pt/sgif2010/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- ICNF. Available online: http://www2.icnf.pt/portal/florestas/dfci/inc/estat-sgif (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- ICNF—Cartografia da Área Ardida. Available online: http://www2.icnf.pt/portal/florestas/dfci/inc/mapas (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Rothermel, R.C. A Mathematical Model for Predicting Fire Spread in Wildland Fuels; Research Paper INT-115; USDA Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1972; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J.D.; Deeming, J.E. The National Fire-Danger Rating System: Basic Equations; General Technical Reports INT-84; USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosberg, M.A. Weather in wildland fire management: The Fire Weather Index. In Proceedings of the Conference on Sierra Nevada Meteorology of the American Meteorological Society and the USDA Forest Service, South Lake Tahoe, CA, USA, 19–21 June 1978; American Meteorological Society: Boston, MA, USA, 1978. 4p. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, D.A. A lower atmosphere severity index for wildland fires. Natl. Weather. Dig. 1988, 13, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Giannaros, T.M.; Papavasileiou, G. Changes in European fire weather extremes and related atmospheric drivers. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 342, 109749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowdy, A.J. Climatological Variability of Fire Weather in Australia. J. App. Meteorol. Clim. 2018, 57, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, R.M.; Garcia-Herrera, R.; Díaz, J.; Trigo, I.F.; Valente, M.A. How exceptional was the early August 2003 heatwave in France? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2005, 32, L10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Gonçalves, N.; Amraoui, M. The Influence of Wildfire Climate on Wildfire Incidence: The Case of Portugal. Fire 2024, 7, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.G.; Trigo, R.M.; da Camara, C.; Pereira, J.; Leite, S.M. Synoptic patterns associated with large summer forest fires in Portugal. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2005, 129, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, R.M.; Pereira, J.; Pereira, M.; Mota, B.; Calado, T.; Da Camara, C.; Santo, F.E. Atmospheric conditions associated with the exceptional fire season of 2003 in Portugal. Int. J. Climatol. 2006, 26, 1741–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.; Parente, J.; Amraoui, M.; Oliveira, A.; Fernandes, P. The role of weather and climate conditions on extreme wildfires. In Extreme Wildfire Events and Disasters; Tedim, F., Leone, V., McGee, T.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 55–72. ISBN 9780128157213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, L.; Russo, A.; Libonati, R.; Trigo, R.M.; Pereira, J.; Benali, A.; Ramos, A.; Gouveia, C.; Rodriguez, C.; Deus, R. Lightning-induced fire regime in Portugal based on satellite-derived and in situ data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2024, 355, 110108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.; Carmo, M.; Rio, J.; Novo, I. Changes in the Seasonality of Fire Activity and Fire Weather in Portugal: Is the Wildfire Season Really Longer? Meteorology 2023, 2, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, P.; Silva, Á.P.; Viegas, D.X.; Almeida, M.; Raposo, J.; Ribeiro, L.M. Influence of Convectively Driven Flows in the Course of a Large Fire in Portugal: The Case of Pedrógão Grande. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, I.C.; Lopes, D.; Fernandes, A.P.; Borrego, C.; Viegas, D.X.; Miranda, A.I. Atmospheric dynamics and fire-induced phenomena: Insights from a comprehensive analysis of the Sertã wildfire event. Atmos. Res. 2024, 310, 107649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kew, S.; Philip, S.; Oldenborgh, G.; der Schier, G.; Otto, F.; Vautard, R. The Exceptional Summer Heat Wave in Southern Europe 2017. Bull. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 100, S49–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPMA. Boletim Climatológico Maio 2017; IPMA: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017; Available online: https://www.ipma.pt/resources.www/docs/im.publicacoes/edicoes.online/20170626/aVLpiPPRcjMelDFtWLhz/cli_20170501_20170531_pcl_mm_co_pt.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025). (In Portuguese)

- FRAMES Catalog. Influence of MCS in Pedrógão Grande Fire Spread. FRAMES 2022, Record No. 65433. Available online: https://www.frames.gov/catalog/65433 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Castellnou, M.; Guiomar, N.; Rego, F.; Fernandes, P.M. Fire growth patterns in the 2017 mega fire episode of October 15, central Portugal. In Advances in Forest Fire Research 2018; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. Five years on … remembering the fires of October 2017. Portugal Resident, 13 October 2022. Available online: https://www.portugalresident.com/five-years-on-remembering-the-fires-of-october-2017/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ramos, A.M.; Russo, A.; DaCamara, C.C.; Nunes, S.; Sousa, P.; Soares, P.M.M.; Lima, M.M.; Hurduc, A.; Trigo, R.M. The compound event that triggered the destructive fires of October 2017 in Portugal. iScience 2023, 26, 106141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, D.X.; Almeida, M.F.; Ribeiro, L.M. (Eds.) Análise dos Incêndios Florestais Ocorridos a 15 de Outubro de 2017. In Centro de Estudos Sobre Incêndios Florestais ADAI/LAETA; Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, C.; Couto, F.T.; Filippi, J.-B.; Baggio, R.; Salgado, R. Modelling pyro-convection phenomenon during a mega-fire event in Portugal. Atmos. Res. 2023, 290, 106776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros, T.; Nunes, J.P.; Pereira, M. Recent evolution of spatial and temporal patterns of burnt areas and fire weather risk in the Iberian Peninsula. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 287, 107923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durão, R.M.; Alonso, C.; Gouveia, C.M. The performance of ECMWF Ensemble Prediction System for European extreme fires: Portugal/Monchique in 2018. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.L.; Couto, F.T.; Salgueiro, V.; Potes, M.; João Costa, M.; Bortoli, D.; Salgado, R. Fire weather risk analysis over Portugal in recent decades: Monchique case study. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2022, Vienna, Austria, 23–27 May 2022; p. EGU22-11616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purificação, C.; Santos, F.; Henkes, A.; Kartsios, S.; Couto, F.T. Fire-weather conditions during two fires in Southern Portugal: Meteorology, Orography, and Fuel Characteristics. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2025, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, M.; Ferreira, J.; Mendes, M.; Silva, A.; Silva, P.; Alves, D.; Reis, L.; Novo, I.; Xavier Viegas, D. The climatology of extreme wildfires in Portugal, 1980–2018: Contributions to forecasting and preparedness. Int. J. Climatol. 2022, 42, 3123–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.; Camprubí, A.C.; Balaguer-Romano, R.; Megía, C.; Castañares, F.; Ruffault, J.; Fernandes, P.; Resco de Dios, V. Drivers and implications of the extreme 2022 wildfire season in Southwest Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 59 Pt 2, 160320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia contributors. Grande Incêndio da Covilhã e Crise na Serra da Estrela; Grandes Incêndios de Portugal de 2022. Available online: https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grandes_Inc%C3%AAndios_de_Portugal_de_2022 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Copernicus. Disastrous Fire in Central Portugal; Copernicus Emergency Management Service. Image of the Day, 17 August 2022. Available online: https://www.copernicus.eu/en/media/image-day-gallery/disastrous-fire-central-portugal (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Gonçalves, J.; Castro, E.; Loureiro, F.; Pereira, P. Assessment of forest fires impacts on geoheritage: A study in the Estrela UNESCO Global Geopark, Portugal. Int. J. Geoherit. Parks 2024, 12, 580–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M.; Barros, A.M.G.; Pinto, A.; Santos, J.A. Characteristics and controls of extremely large wildfires in the western Mediterranean Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2016, 121, 2141–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Garroussi, S.; Di Giuseppe, F.; Barnard, C.; Wetterhall, F. Europe faces up to tenfold increase in extreme fires in a warming climate. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedia, J.; Golding, N.; Casanueva, A.; Iturbide, M.; Buontempo, C.; Gutiérrez, J.M. Seasonal predictions of Fire Weather Index: Paving the way for their operational applicability in Mediterranean Europe. Clim. Serv. 2018, 9, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wagner, C.E.; Pickett, T.L. Equations and FORTRAN Program for the Canadian Forest Fire Weather Index System; Forestry Technical Report 33; Canadian Forestry Service, Petawawa National Forestry Institute: Chalk River, ON, Canada, 1985; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

| FWI | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0–8.5 | Very low |

| 8.5–17.3 | Low |

| 17.3–24.7 | Moderate |

| 24.7–38.3 | High |

| 38.3–50.1 | Very high |

| 50.1–64 | Extreme/Maximum |

| >64 |

| Fire Event | 09 UTC | 12 UTC | 15 UTC | 18 UTC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamusca 2003 | P95 | >P95 | >P95 | P95 |

| Pedrógão 2017 | P50 | P90 | >P95 | P90 |

| Lousã 2017 | >P95 | >P95 | >P95 | >P95 |

| Monchique 2018 | >P95 | >P95 | P90 | P50 |

| Covilhã 2022 | P75 | P90 | P90 | P90 |

| Event (Date) | Region | HDW at Ignition | FWI at Ignition | Interpretation | FWI Duration > 50 (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamusca (2 August 2003) | Santarém | 363.57 | 65.16 | Extreme | 4 |

| Pedrógão (17 June 2017) | Leiria/Castelo Branco | 88.61 | 39.53 | Very high | 2 |

| Lousã (15 October 2017) | Coimbra | 193.70 | 35.96 | High | 1 |

| Monchique (3 August 2018) | Algarve | 222.07 | 64.57 | Extreme | 5 |

| Covilhã (6 August 2022) | Serra da Estrela | 77.94 | 53.24 | Extreme | 6 |

| Fire Event | Spearman rho (HDW vs. FWI) | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chamusca 2003 | 0.5250 | 0.0471 | Moderate positive correlation, statistically significant at α = 0.05. HDW and FWI concurrently before ignition, capturing the fire danger consistently. This suggests some agreement between HDW and FWI trends but also highlights periods where they diverge. |

| Pedrógão Grande 2017 | 0.7250 | 0.0031 | Strong positive correlation and statistically significant, showing that FWI and HDW co-varied closely, supporting a robust alignment of both indices during this event. |

| Lousã 2017 | 0.5 | 0.0602 | Moderate positive correlation, with no significance, showing that FWI and HDW co-varied closely, indicating some decoupling between HDW and FWI. |

| Monchique 2018 | 0.6857 | 0.0062 | Moderate-to-strong, significant positive correlation, indicating that HDW and FWI consistently reflected elevated fire danger. This case strengthens confidence in the compound indicator coherence. |

| Covilhã 2022 | −0.1679 | 0.5493 | Weak negative correlation, not statistically significant, highlighting an inverse relationship. FWI remained high while HDW declined, revealing sensitivity to different fire weather drivers. This implies that the HDW peak did not coincide with FWI extremes, again suggesting that HDW adds unique information not captured by FWI. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andrade, C.; Bugalho, L. Fire Danger Climatology Using the Hot–Dry–Windy Index: Case Studies from Portugal. Forests 2025, 16, 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091417

Andrade C, Bugalho L. Fire Danger Climatology Using the Hot–Dry–Windy Index: Case Studies from Portugal. Forests. 2025; 16(9):1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091417

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndrade, Cristina, and Lourdes Bugalho. 2025. "Fire Danger Climatology Using the Hot–Dry–Windy Index: Case Studies from Portugal" Forests 16, no. 9: 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091417

APA StyleAndrade, C., & Bugalho, L. (2025). Fire Danger Climatology Using the Hot–Dry–Windy Index: Case Studies from Portugal. Forests, 16(9), 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091417