The Impact and Mechanism of the Natural Forest Logging Ban Policy on Rural Residents’ Income: A Case Study of China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Institutional Background and Theoretical Assumptions

2.1. Institutional Background

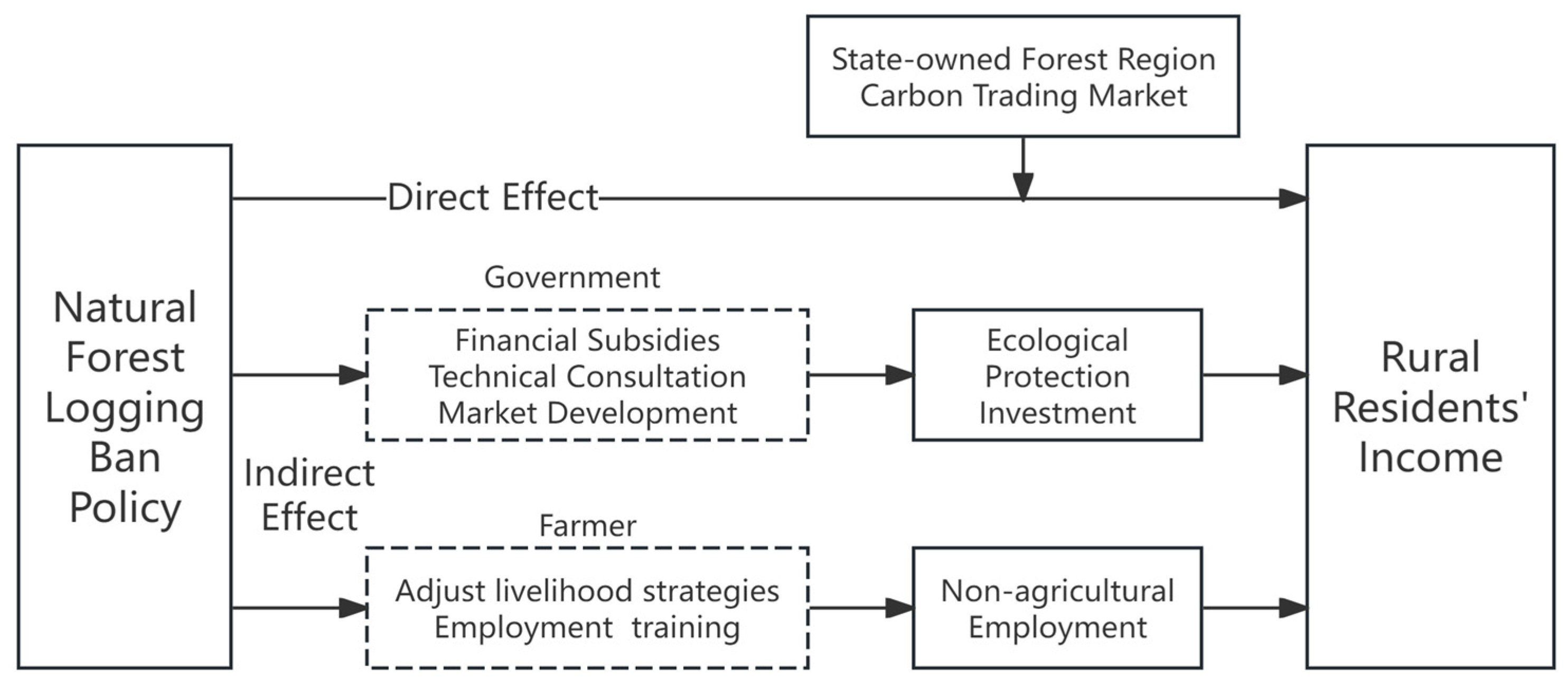

2.2. Theoretical Assumptions

2.2.1. Direct Impact of the Natural Forest Logging Ban Policy on Rural Residents’ Income

2.2.2. Indirect Impact of the Natural Forest Logging Ban Policy on Rural Residents’ Income

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Models

3.1.1. Baseline Regression Model

3.1.2. Mediation Effect Model

3.2. Variable Selection

3.2.1. Explained Variable

3.2.2. Core Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Mechanism Variables

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.3. Data Description

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Benchmark Regression Results

4.2. Test of Structural Effects

4.3. Validity Test of the Model

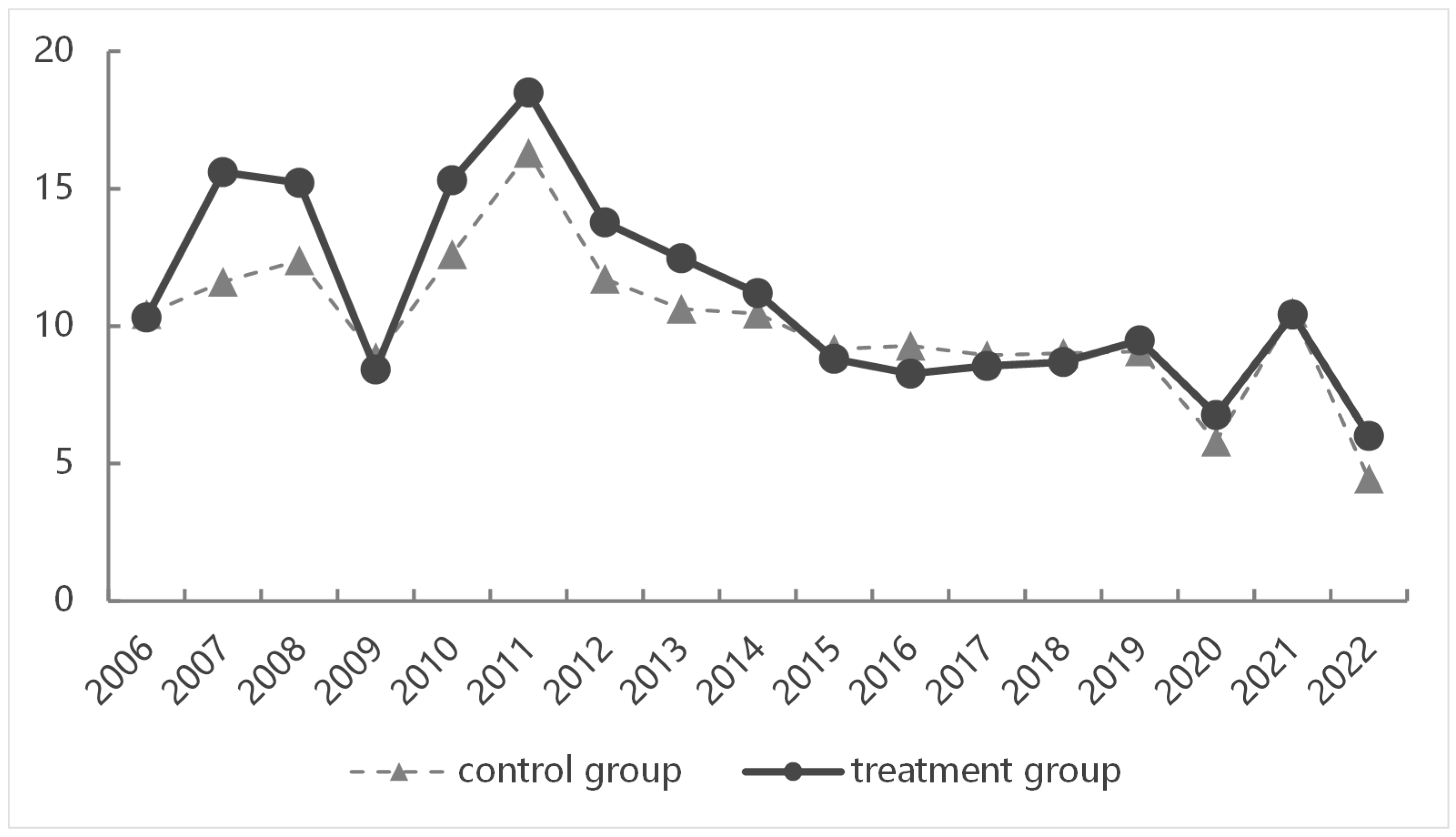

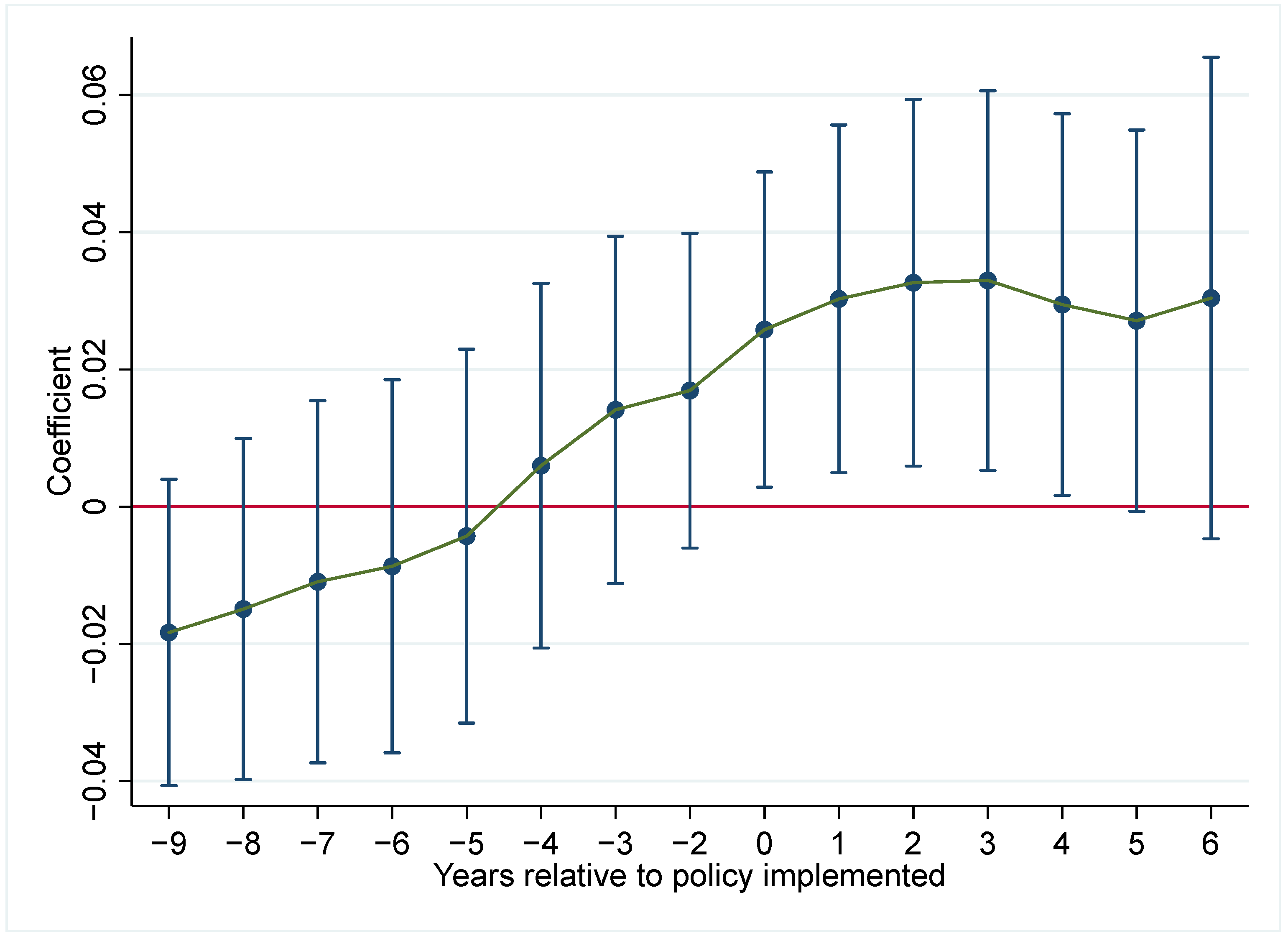

4.3.1. Parallel Trend Test

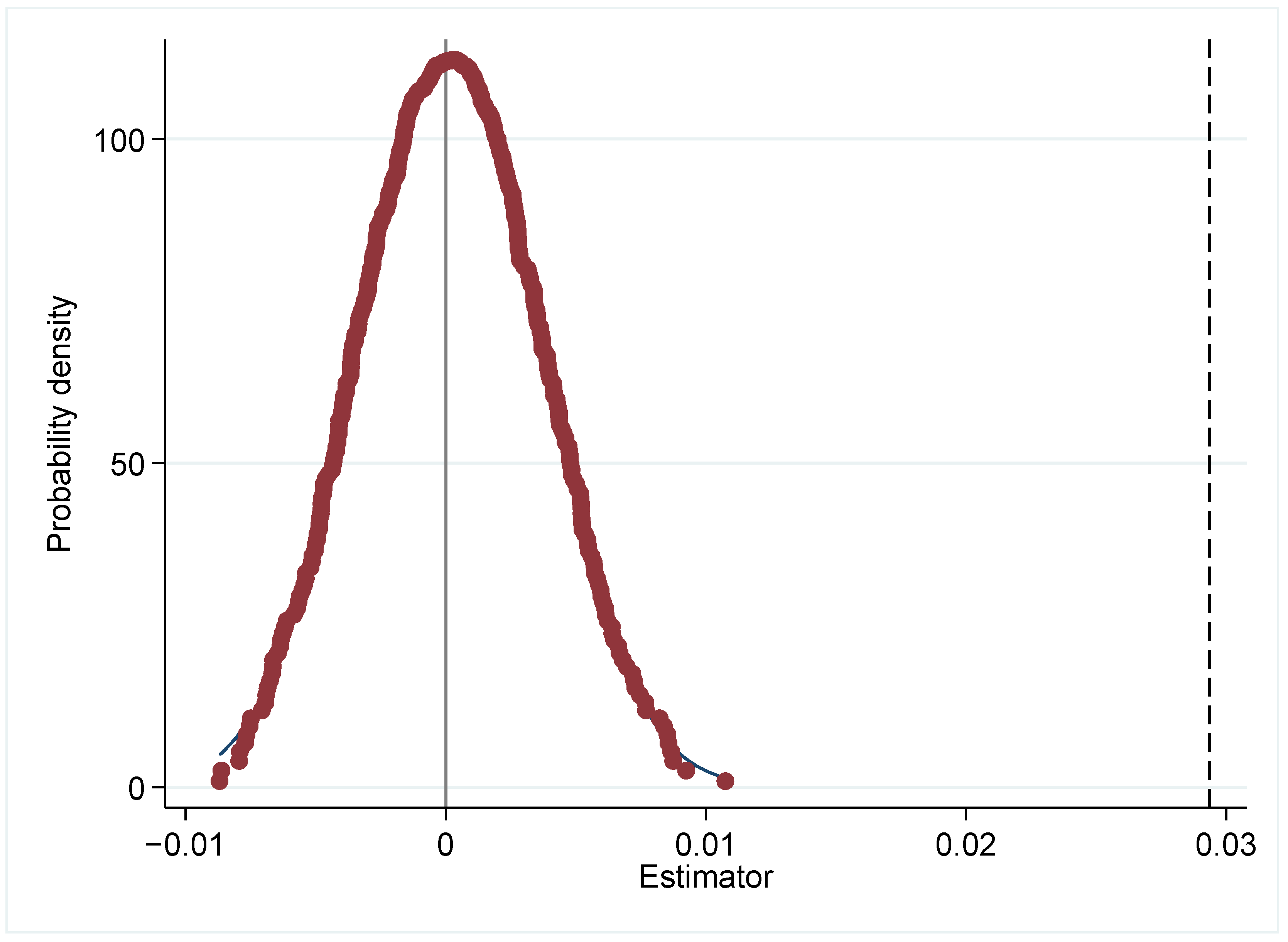

4.3.2. Placebo Test

4.4. Robustness Test

4.4.1. Excluding Concurrent Policies

4.4.2. Winsorization

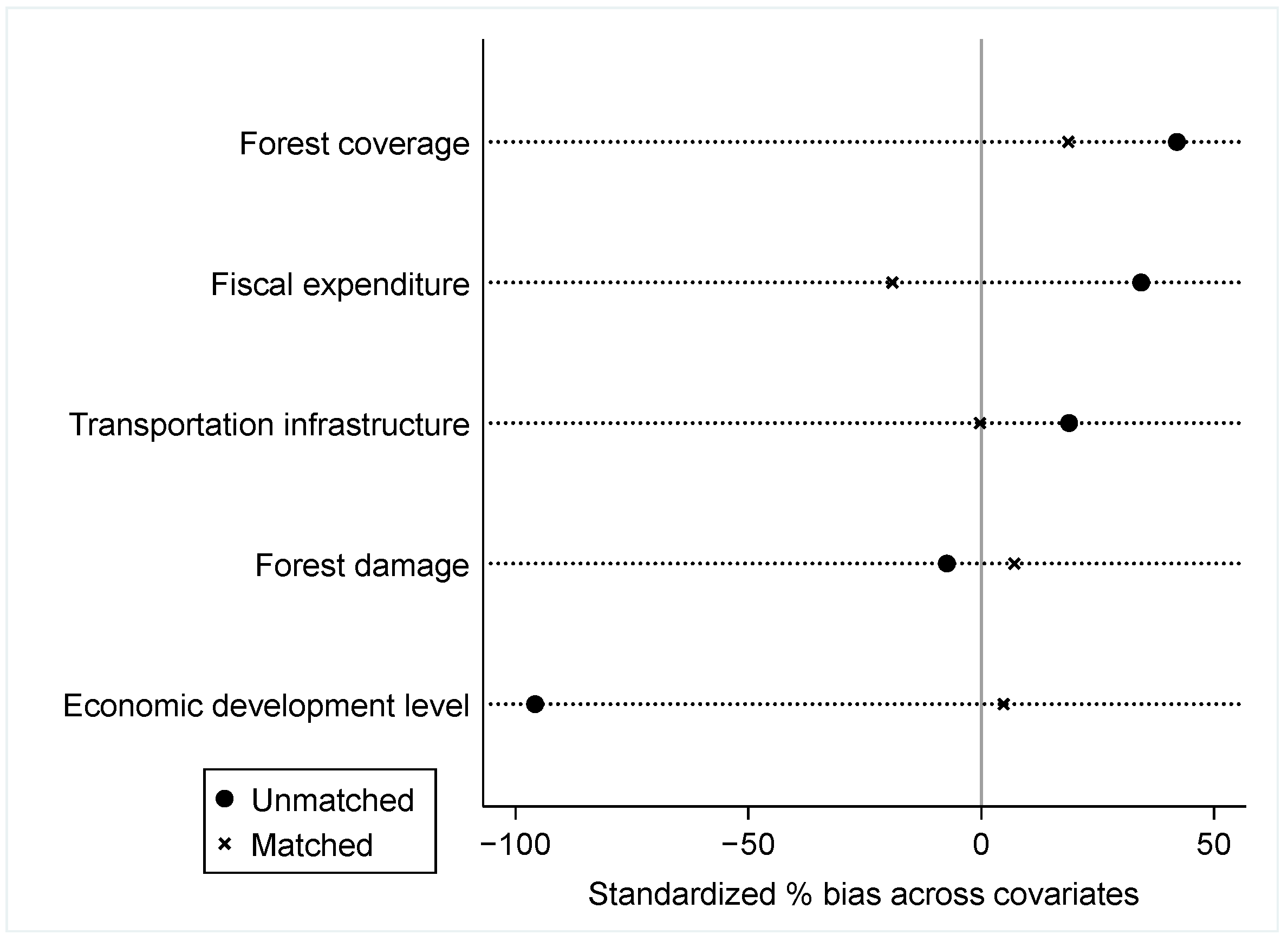

4.4.3. PSM-DID Test

4.5. Mechanism Analysis

4.5.1. Test Effect Results of Non-Agricultural Employment

4.5.2. Results of Testing the Effect of Forest Ecological Protection Investment

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.6.1. Impact of the Carbon Trading Market

4.6.2. Impact on State-Owned Forest Areas

5. Discussion and Policy Implications

- (1)

- Strengthen the natural forest protection policy system. Considering the positive effect of the NFLBP on rural income, the policy framework should be continuously improved in three key areas:Enhance the forest protection and management system. Establish and optimize natural forest conservation institutions. At the national level, clearly define the responsibilities of the National Forestry and Grassland Administration. At the local level, build or improve institutions for forest protection and management at all administrative tiers to form a coordinated and unified governance structure.Promote fundamental research on natural forest conservation. Support scientific institutions in studying the structure, function, and succession of natural forest ecosystems and developing key technologies for ecological restoration. Improve mechanisms for translating research outcomes into practical applications, and apply advanced tools such as remote sensing and GIS to enhance monitoring and management.Expand public participation channels. Strengthen information disclosure to safeguard public access to information, and establish effective procedures for citizen involvement in decision-making. Conduct multi-platform education and awareness campaigns to raise ecological protection consciousness across society.

- (2)

- Improve mechanisms to increase rural income.Diversify compensation mechanisms. In addition to existing fiscal compensation, develop market-based ecological compensation channels and create mechanisms for realizing the economic value of ecological products, such as carbon trading. Encourage social capital participation in forest conservation to broaden funding sources. Adjust compensation standards and methods according to regional differences and ecological values, and develop innovative, differentiated approaches.Establish multi-stakeholder training networks. Involve government, enterprises, and individuals in planning and delivering training programs. Facilitate the transition of forest-area rural residents from forestry to non-agricultural sectors, linking employment opportunities with income growth. Promote a virtuous cycle of “skill improvement → employment → income growth” to create endogenous drivers for rural income enhancement.Leverage forest resources to develop emerging industries. Utilize ecological advantages to promote forest ecotourism, forest health services, and diversified forest-based industries. Expand local employment opportunities and alleviate the pressure of rural labor outflow.

- (3)

- Implement region-specific forestry development strategies.Adopt differentiated development paths. Set targeted forestry development objectives, resource cultivation plans, and industrial structural optimization strategies based on regional resource endowments and development stages. Dynamically adjust factor allocation within the forestry system to improve resource utilization efficiency.Transform ecological advantages into development momentum. In regions rich in natural forests, deepen technical exchanges and management experience with developed areas, innovate forestry management models, and unlock resource potential through institutional reform.Promote low-carbon forestry in carbon trading pilot areas. Build platforms for the circulation of production factors, including technology, talent, and capital, across regions. Rely on carbon sink market mechanisms to enhance resource efficiency and establish replicable low-carbon development models.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Howley, P.; Dillon, E.; Heanue, K.; Meredith, D. Worth the risk? The behavioural path to well-being. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 68, 534–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Chen, S. How did the comprehensive commercial logging ban policy affect the life satisfaction of residents in national forest areas? A case study in Northeast China and Inner Mongolia. Forests 2023, 14, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viña, A.; McConnell, W.J.; Yang, H.; Xu, Z.; Liu, J. Effects of conservation policy on China’s forest recovery. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1500965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, B.A.; Gao, L.; Ye, Y.; Sun, X.; Connor, J.D.; Crossman, N.D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Wu, J.; He, C.; Yu, D.; et al. China’s response to a national land-system sustainability emergency. Nature 2018, 559, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hu, S. The Effect on Livelihood Styles Differentiation of Worker Households in Key National Forest Areas by Comprehensive “Stop Cutting” Policy. For. Econ. 2016, 38, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.; Ye, D.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Q. Financial compensation for natural forest logging ban: Standard calculation based on willingness to accept. Sci. Prog. 2023, 106, 00368504221145563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Sun, S.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Impact of forest logging ban on the welfare of local communities in northeast China. Forests 2020, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Q. Changes of China’s forestry and forest products industry over the past 40 years and challenges lying ahead. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 123, 102352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L.; Fang, L.; Chen, W. Research on development level and spatial distribution characteristics of state-owned forest farms in China. For. Econ. Rev. 2022, 4, 56–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yan, R.; Ye, P.; Dong, J.; Zhang, N.; He, X.; Zhao, R. Does the Comprehensive Commercial Logging Ban Policy in All Natural Forests Affect Farmers’ Income?—An Empirical Study Based on County-Level Data in China. Forests 2024, 15, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzi, M.; Prete, C.; Viccaro, M.; Romano, S. Impacts of wildlife on agriculture: A spatial-based analysis and economic assessment for reducing damage. Nat. Resour. Res. 2019, 28 (Suppl. S1), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wen, Y.; Duan, W.; Han, F. Coupling relationship analysis on households’ production behaviors and their influencing factors in nature reserves: A structural equation model. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 23, 506–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Zhang, Y. The impact of changes in log import price from the logging ban on the market price of timber products. J. Sustain. For. 2023, 42, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Chen, Y. How forest subsidies impact household income: The case from China. Forests 2021, 12, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecký, V. Contribution of afforestation subsidies policy to climate change adaptation in the Czech Republic. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopp, C.; Engler, A.; Jara-Rojas, R.; Arriagada, R. Are forest plantation subsidies affecting land use change and off-farm income? A farm-level analysis of Chilean small forest landowners. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhao, X. Has the development of the non-timber forest products industry achieved poverty alleviation? Evidence from lower-income forest areas in Yunnan Province. Forests 2023, 14, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, F.D.P.; Tegegne, Y.T.; Winkel, G.; Cerutti, P.O.; Ramcilovic-Suominen, S.; McDermott, C.L.; Zeitlin, J.; Sotirov, M.; Cashore, B.; Wardell, D.A.; et al. Effects of EU illegal logging policy on timber-supplying countries: A systematic review. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 327, 116874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Harada, K.; Dahal, N.K.; Gurung, R. Scientific forest management practices in Nepal: Perceptions of forest users and the impact on their livelihoods. J. For. Res. 2024, 29, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Peasant Economics: Farm Households in Agrarian Development; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Zhu, W. Why did the 1980s’ reform of collective forestland tenure in southern China fail? For. Policy Econ. 2017, 83, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, F.; Guan, X. Examining the impact of forestry policy on poor and non-poor farmers’ income and production input in collective forest areas in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 276, 123784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Huang, C. How forestland size affects household profits from timber harvests: A case-study in China’s southern collective forest area. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 103380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xu, J. Livelihood mushroomed: Examining household level impacts of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) under new management regime in China’s state forests. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 98, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Bhojvaid, P.; de Jong, W.; Ashraf, J.; Reddy, S. Forest transition and socio-economic development in India and their implications for forest transition theory. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 76, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, A.; Javakhishvili-Larsen, N.; Schmidt, T.D. Labour mobility and local employment: Building a local employment base from labour mobility? Reg. Stud. 2017, 51, 1622–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Klaiber, H.A.; Miteva, D.A. Impacts of forest conservation on local agricultural labor supply: Evidence from the Indonesian forest moratorium. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2023, 105, 940–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Weng, F.; Huo, X. Can digital finance promote professional farmers’ income growth in China?—An examination based on the perspective of income structure. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalyshyn, V.; Holovko, A.; Yaremak, Z.; Dudiuk, V. Impact of forestry on ecosystems and the economy: Regional case studies. Sci. J. Ukr. J. For. Wood Sci. 2023, 14, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.K.; Hayes, A.F. Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychol. Methods 2017, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Ma, J. Does digital finance benefit the income of rural residents? A case study on China. Quant. Financ. Econ. 2021, 5, 664–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, B.; Sant’Anna, P.H.C. Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. J. Econom. 2021, 225, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, P.; Kumar, R.; Sivaramane, N.; Kumar, S.; Srinivas, K.; Dhandapani, A.; Khan, E. Non-farm income as an instrument for doubling farmers’ income: Evidences from longitudinal household survey. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2017, 30, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giller, K.E.; Delaune, T.; Silva, J.V.; van Wijk, M.; Hammond, J.; Descheemaeker, K.; van de Ven, G.; Schut, A.G.T.; Taulya, G.; Chikowo, R.; et al. Small farms and development in sub-Saharan Africa: Farming for food, for income or for lack of better options? Food Secur. 2021, 13, 1431–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xin, L.; Wang, Y. How farmers’ non-agricultural employment affects rural land circulation in China? J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Fan, M.; Yang, L.; Shao, S. Heterogeneous green innovations and carbon emission performance: Evidence at China’s city level. Energy Econ. 2021, 99, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, S. Wood trade responses to ecological rehabilitation program: Evidence from China’s new logging ban in natural forests. For. Policy Econ. 2021, 122, 102339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, L.S.; LaLonde, R.J.; Sullivan, D.G. Earnings losses of displaced workers. Am. Econ. Rev. 1993, 83, 685–709. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J. Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 123, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Li, S.; Zhou, W.; Qi, L.; Zhou, L.; Wei, Y.; Li, J.; Shao, G.; Yu, D. Opportunities and challenges for the protection and ecological functions promotion of natural forests in China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 410, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Zhan, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Qi, W. Assessment on forest carbon sequestration in the Three-North Shelterbelt Program region, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ren, Y.; Hong, Y.; Glauben, T. Does forest farm carbon sink projects affect agricultural development? Evidence from a Quasi-experiment in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 335, 117500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, D.; Zhao, M.; Wang, K. Do impoverished regions benefit from climate change mitigation measures? Evidence from the Forest Carbon Sink Project in China. Clim. Policy 2025, 25, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Ling, W.; Sheng, C.-L.; Deng, Y.; Li, X.-M. Design of ecological carbon sink compensation mechanism for national parks based on carbon trading. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 2294–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zhang, N. The effect of China’s pilot carbon emissions trading schemes on poverty alleviation: A quasi-natural experiment approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 110973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cheng, B.; Diao, G.; Tao, C.; Wang, C. Does China’s natural forest logging ban affect the stability of the timber import trade network? For. Policy Econ. 2023, 152, 102974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhu, H.; Qi, J.; Tian, G. Well-being of forestry workers and affecting factors after complete cessation of commercial logging of natural forests: Based on the data of Northeastern key state-owned forest areas of China. Resour. Sci. 2019, 41, 669–680. [Google Scholar]

| Policy Implemented | Study Period (2005–2022) | Province | Ratio of Natural Forests (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018–2022 | |||

| 2014 | Before | Post | Post | Post | Post | Post | Heilongjiang | 15.81 |

| 2015 | Before | Before | Post | Post | Post | Post | Inner Mongolia and Jilin | 32.25 |

| 2016 | Before | Before | Before | Post | Post | Post | Hebei, Fujian, Jiangxi, Hubei, Hunan, Guangxi, Yunnan | 77.04 |

| 2017 | Before | Before | Before | Before | Post | Post | Other provinces | 100.00 |

| Variable | Number of Samples | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural residents’ income | 540 | 10,960.08 | 6805.97 | 1971 | 39,729 |

| NFLBP | 540 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 |

| Economic development level (%) | 540 | 12.25 | 7.18 | −5.34 | 66.92 |

| Transportation infrastructure (%) | 540 | 0.91 | 0.52 | 0.04 | 2.28 |

| Forest coverage (%) | 540 | 32.79 | 18.01 | 3.16 | 67.48 |

| Forest damage (%) | 540 | 9.52 | 10.87 | 0.36 | 80.89 |

| Fiscal expenditure (%) | 540 | 23.77 | 10.70 | 9.19 | 75.83 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural Residents’ Income | Rural Residents’ Income | Rural Residents’ Income | Rural Residents’ Income | |

| NFLBP | 0.0286 *** (0.0098) | 0.0292 *** (0.0097) | 0.0295 *** (0.0096) | 0.0293 *** (0.0096) |

| Economic development level | 0.0007 (0.0004) | 0.0008 * (0.0004) | 0.0008 * (0.0004) | |

| Transportation infrastructure | 0.0555 *** (0.0157) | 0.0446 *** (0.0163) | 0.0565 *** (0.0167) | |

| Forest coverage | 0.0021 ** (0.0009) | 0.0027 *** (0.0009) | ||

| Forest damage | 0.0009 * (0.0005) | 0.0009 * (0.0005) | ||

| Fiscal expenditure | 0.0018 *** (0.0006) | |||

| Constant term | 8.1221 *** (0.0072) | 8.0848 *** (0.0127) | 8.0232 *** (0.0281) | 7.9722 *** (0.0331) |

| Time fixed effects | control | control | control | control |

| Province fixed effects | control | control | control | control |

| N | 540 | 540 | 540 | 540 |

| R2 | 0.995 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wage Income | Operational Income | Property Income | Transfer Income | |

| NFLBP | 0.1037 *** (0.0341) | 0.0145 (0.0294) | 0.1471 ** (0.0733) | 0.0537 (0.0660) |

| Economic development level | 0.0017 (0.0015) | 0.0038 *** (0.0013) | 0.0023 (0.0032) | 0.0012 (0.0029) |

| Transportation infrastructure | −0.1187 ** (0.0595) | 0.1043 ** (0.0513) | 0.4848 *** (0.1279) | 0.5033 *** (0.1152) |

| Forest coverage | 0.0011 (0.0034) | −0.0155 *** (0.0029) | 0.0007 (0.0072) | 0.0017 (0.0065) |

| Forest damage | 0.0016 (0.0018) | −0.0002 (0.0016) | 0.0050 (0.0039) | 0.0163 *** (0.0035) |

| Fiscal expenditure | 0.0100 *** (0.0022) | −0.0011 (0.0019) | 0.0061 (0.0048) | 0.0045 (0.0043) |

| Constant term | 6.7598 *** (0.1179) | 7.8114 *** (0.1017) | 3.8548 *** (0.2534) | 4.4660 *** (0.2283) |

| Time fixed effects | control | control | control | control |

| Province fixed effects | control | control | control | control |

| N | 540 | 540 | 540 | 540 |

| R2 | 0.958 | 0.928 | 0.793 | 0.951 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excluding the Collective Forest Tenure Reform | Excluding the Natural Forest Protection Project | Excluding the Forest Chief System Reform | |

| NFLBP | 0.0292 *** (0.0096) | 0.0171 ** (0.0085) | 0.0290 *** (0.0096) |

| Collective forest tenure reform | 0.0107 (0.0101) | ||

| Natural forest protection project | 0.0783 *** (0.0065) | ||

| Forest chief system reform | 0.0057 (0.0083) | ||

| Economic development level | 0.0008 * (0.0004) | 0.0008 ** (0.0004) | 0.0007 * (0.0004) |

| Transportation infrastructure | 0.0564 *** (0.0167) | 0.0677 *** (0.0147) | 0.0578 *** (0.0168) |

| Forest coverage | 0.0026 *** (0.0009) | 0.0017 ** (0.0008) | 0.0028 *** (0.0010) |

| Forest damage | 0.0008 (0.0005) | 0.0014 *** (0.0005) | 0.0009 * (0.0005) |

| Fiscal expenditure | 0.0017 *** (0.0006) | 0.0001 (0.0006) | 0.0018 *** (0.0006) |

| Constant term | 7.9742 *** (0.0331) | 8.0177 *** (0.0293) | 7.9689 *** (0.0334) |

| Time fixed effects | control | control | control |

| Province fixed effects | control | control | control |

| N | 540 | 540 | 540 |

| R2 | 0.996 | 0.997 | 0.996 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1% Reduction | 1% Reduction | 5% Reduction | 5% Reduction | |

| NFLBP | 0.0371 *** (0.0101) | 0.0378 *** (0.0099) | 0.1008 *** (0.0174) | 0.0951 *** (0.0166) |

| Economic development level | 0.0002 (0.0005) | 0.0004 (0.0010) | ||

| Transportation infrastructure | 0.0599 *** (0.0176) | 0.2206 *** (0.0304) | ||

| Forest coverage | 0.0018 * (0.0010) | −0.0065 *** (0.0015) | ||

| Forest damage | 0.0012 ** (0.0006) | −0.0008 (0.0012) | ||

| Fiscal expenditure | 0.0017 ** (0.0007) | −0.0007 (0.0014) | ||

| Constant term | 8.1291 *** (0.0074) | 8.0093 *** (0.0349) | 8.2007 *** (0.0128) | 8.2924 *** (0.0567) |

| Time fixed effects | control | control | control | control |

| Province fixed effects | control | control | control | control |

| N | 540 | 540 | 540 | 540 |

| R2 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.985 | 0.986 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nearest Neighbor Matching | Kernel Matching Method | Radius Matching Method | |

| NFLBP | 0.0176 * (0.0091) | 0.0176 ** (0.0089) | 0.0284 *** (0.0094) |

| Economic development level | −0.0005 (0.0006) | −0.0006 (0.0006) | 0.0007 * (0.0004) |

| Transportation infrastructure | 0.0464 ** (0.0182) | 0.0455 ** (0.0179) | 0.0484 *** (0.0171) |

| Forest coverage | 0.0019 * (0.0010) | 0.0020 ** (0.0010) | 0.0019 * (0.0010) |

| Forest damage | 0.0004 (0.0005) | 0.0004 (0.0005) | 0.0009 * (0.0005) |

| Fiscal expenditure | 0.0010 (0.0006) | 0.0008 (0.0006) | 0.0019 *** (0.0006) |

| Constant term | 8.0245 *** (0.0352) | 8.0266 *** (0.0347) | 7.9960 *** (0.0339) |

| Time fixed effects | control | control | control |

| Province fixed effects | control | control | control |

| N | 476 | 473 | 528 |

| R2 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Agricultural Employment | Forest Ecological Protection Investment | |

| NFLBP | 2.8444 *** (0.9362) | 0.1744 ** (0.0749) |

| Economic development level | 0.0405 (0.0415) | −0.0043 (0.0033) |

| Transportation infrastructure | 7.4573 *** (1.6340) | −0.1055 (0.1308) |

| Forest coverage | 0.1422 (0.0924) | 0.0303 *** (0.0074) |

| Forest damage | −0.0643 (0.0502) | 0.0034 (0.0040) |

| Fiscal expenditure | 0.0383 (0.0609) | 0.0091 * (0.0049) |

| Constant term | 47.6793 *** (3.2377) | −0.7259 *** (0.2592) |

| Time fixed effects | control | control |

| Province fixed effects | control | control |

| N | 540 | 540 |

| R2 | 0.759 | 0.298 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Rural Residents’ Income | Rural Residents’ Income | |

| Triple difference term | −0.0257 *** (0.0089) | −0.0380 *** (0.0090) |

| Economic development level | 0.0007 (0.0004) | |

| Transportation infrastructure | 0.0628 *** (0.0166) | |

| Forest coverage | 0.0035 *** (0.0010) | |

| Forest damage | 0.0010 ** (0.0005) | |

| Fiscal expenditure | 0.0017 *** (0.0006) | |

| Constant term | 8.1221 *** (0.0072) | 7.9467 *** (0.0333) |

| Time fixed effects | control | control |

| Province fixed effects | control | control |

| N | 540 | 540 |

| R2 | 0.995 | 0.996 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Rural Residents’ Income | Rural Residents’ Income | |

| Triple difference term | 0.0345 *** (0.0074) | 0.0553 *** (0.0076) |

| Economic development level | 0.0009 ** (0.0004) | |

| Transportation infrastructure | 0.0927 *** (0.0168) | |

| Forest coverage | 0.0038 *** (0.0009) | |

| Forest damage | 0.0008 (0.0005) | |

| Fiscal expenditure | 0.0019 *** (0.0006) | |

| Constant term | 8.1221 *** (0.0071) | 7.9195 *** (0.0325) |

| Time fixed effects | control | control |

| Province fixed effects | control | control |

| N | 540 | 540 |

| R2 | 0.996 | 0.996 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Liao, W.; Zhang, X. The Impact and Mechanism of the Natural Forest Logging Ban Policy on Rural Residents’ Income: A Case Study of China. Forests 2025, 16, 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091413

Liu Y, Peng Y, Liao W, Zhang X. The Impact and Mechanism of the Natural Forest Logging Ban Policy on Rural Residents’ Income: A Case Study of China. Forests. 2025; 16(9):1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091413

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yang, Yuanyuan Peng, Wenmei Liao, and Xu Zhang. 2025. "The Impact and Mechanism of the Natural Forest Logging Ban Policy on Rural Residents’ Income: A Case Study of China" Forests 16, no. 9: 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091413

APA StyleLiu, Y., Peng, Y., Liao, W., & Zhang, X. (2025). The Impact and Mechanism of the Natural Forest Logging Ban Policy on Rural Residents’ Income: A Case Study of China. Forests, 16(9), 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16091413