3.2.1. Challenges in Carbon Rights Policymaking Process

Transforming carbon into a new form of property supports REDD+ by recognizing the value in maintaining carbon stocks and sequestering carbon in forests. However, such activities generate revenue only if appropriate emissions trading systems or fund-based compensation mechanisms are established to support the trading of carbon rights.

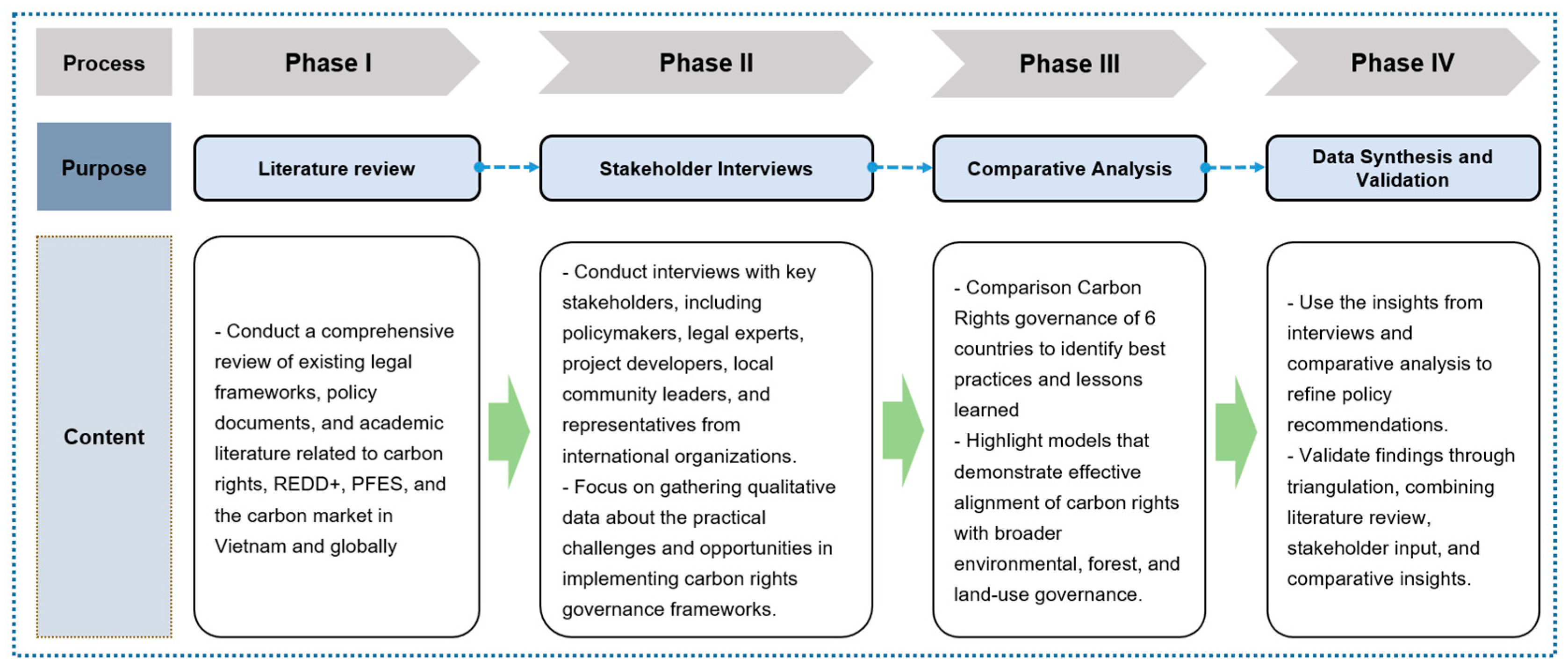

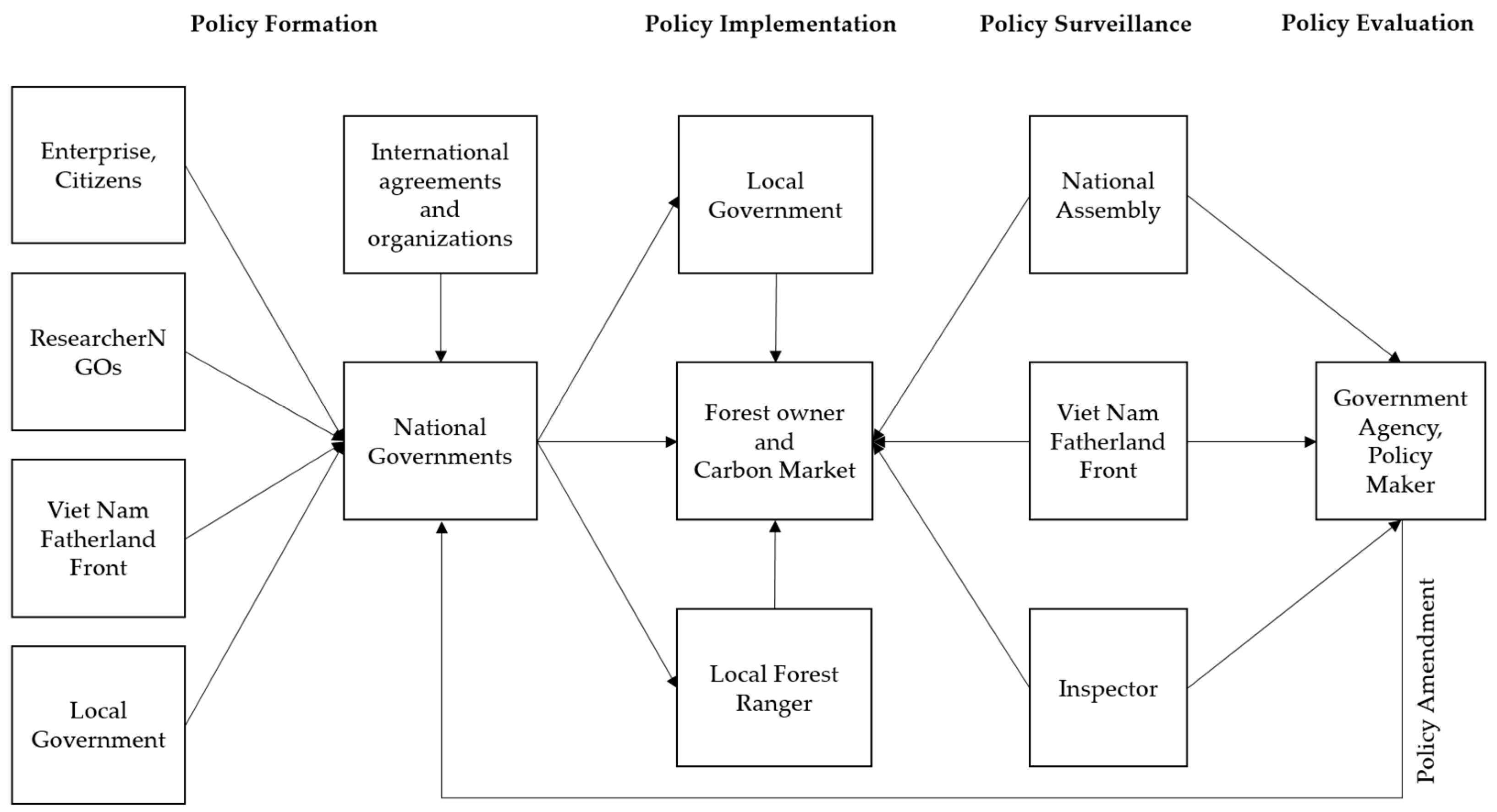

Figure 2 illustrated the challenges Vietnam faces in developing a Carbon Rights policy. Vietnam, like many other nations, confronts significant challenges in defining carbon rights, managing carbon reduction distribution certificates, facilitating carbon transfers, and establishing financial management and benefit-sharing mechanisms [

9]. A robust legal framework to define and allocate carbon rights is a relatively new challenge, necessitating extensive efforts, stakeholder engagement, and significant financial resources. The policymaking process in this area is generally lengthy and depends on the country’s developmental orientation and institutional capacities.

Vietnam’s carbon market strategy necessitates a comprehensive evaluation of pivotal policy elements, including market structure, integration, and financial management. The distinction between compulsory and voluntary carbon markets is crucial, as a compulsory system corresponds with the Paris Agreement to enhance access to international finance, while a voluntary market offers increased flexibility, particularly beneficial for forestry-related projects, and facilitates private sector engagement and administrative enhancements. Furthermore, the integration of domestic and international markets requires a robust legal framework for carbon credit registration, appraisal, and trading mechanisms, coupled with the establishment of financial support systems to ensure seamless market participation. Additionally, effective financial management and benefit-sharing mechanisms are crucial to define implementation costs, beneficiary structures, and payment frameworks, ensuring transparency, equitable distribution, and stakeholder trust. Strengthening these components will facilitate Vietnam’s transition to a well-regulated, inclusive, and internationally competitive carbon market.

Developing a robust carbon transfer policy requires addressing these challenges through inclusive, transparent, and adequately supported strategies. These initiatives will not only ensure Vietnam’s compliance with international norms but also promote sustainable development and enhance climate resilience.

3.2.2. Examination of Legal, Policy, and Management Frameworks in Vietnam

Carbon rights in Vietnam are intrinsically tied to the country’s environmental services, which have developed over decades. These frameworks prioritize public benefit, particularly in new policy areas such as carbon rights, which initially focus on state forest management. Early identification of beneficiaries is crucial to avoid complexities in sharing REDD+ outcomes.

Vietnam is one of the few countries in Asia with a well-defined legal framework recognizing the critical role of forest carbon in climate change adaptation and mitigation. This framework also facilitates forest carbon trading. Vietnam’s policy framework for forest carbon rights originated with the Civil Code from 2015, which broadly defined property to include certified carbon credits as forest assets. Recognizing these credits established a foundation for treating forest carbon as a valuable asset, aligning Vietnam’s legal system with international trends in carbon governance. The Forestry Law from 2017 expanded this framework by explicitly recognizing forest carbon sequestration and storage as one of five forest environmental services under Article 61. It also introduced benefit-sharing mechanisms, delineated in Article 73, to ensure that revenues from forest environmental services, including those related to carbon, benefit forest owners and communities. Yet, the development of practical regulations for implementing these services was limited, underlining significant implementation challenges despite the law’s ambitious provisions.

Building upon these foundational laws, Vietnam introduced Decree No. 156/2018, which provided detailed guidance on managing payments for forest environmental services. Articles 64 to 75 of the decree addressed the financial management and allocation of these payments but lacked specific mechanisms for carbon sequestration services. A notable advancement occurred with Decree No. 107/2022, which piloted carbon payment mechanisms for forest environmental services in the North Central Region. This decree established procedures for distributing revenues based on emissions reduction results, underscoring the importance of benefit-sharing at provincial and community levels. Moreover, the Environmental Protection Law from 2020 was a turning point, formalizing the development of a domestic carbon market and enabling the trading of carbon credits and emission quotas. These legal and policy developments were supported by Vietnam’s updated Nationally Determined Contributions in 2022, which committed to ambitious emissions reduction targets through forest conservation, sustainable management, and carbon market participation. Collectively, these measures demonstrate Vietnam’s dedication to establishing a comprehensive framework for forest carbon rights, while addressing the practical implementation gaps and optimizing benefit-sharing.

Vietnam’s legal and policy framework underscores the progressive strides taken to institute a comprehensive carbon rights regime. However, challenges such as the absence of specific regulations for forest carbon sequestration services and their effective implementation persist. Continuous refinement along with stakeholder engagement is essential to enhance governance and fulfill Vietnam’s climate commitments.

3.2.3. International Lessons Learned from 7 Countries

In Vietnam, carbon rights are closely linked to the nation’s environmental services, evolving over several decades. These frameworks are designed to prioritize public benefit, especially in emerging areas such as carbon policy.

The case study selection for comparative analysis encompassed seven countries: Australia, New Zealand, Sweden, Brazil, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Indonesia, and the Philippines as detailed in

Table 2. Australia and New Zealand were selected for their sophisticated carbon rights management policies, owing to their leadership in the development and implementation of carbon governance frameworks. Sweden was selected as representative of European Union that involved in Emission Trading System EU ETS. Sweden’s carbon tax from 1991 and the EU Emissions Trading System aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through gradually increasing taxes and a decreasing emissions cap, respectively [

30]. Sweden’s carbon tax targets fossil fuels in the energy sector, with growing exemptions for EU ETS-covered installations, including district heating plants since 2014 [

31]. Brazil is the biggest country for forest with long history of REDD+ implementation. The Democratic Republic of Congo was included because of its involvement in Emission Reductions Payment Agreements (ERPAs), which underpin the foundation of Vietnam’s ongoing policy initiatives. The ERPAs in Vietnam represent the initial efforts in formalizing revenue-sharing mechanisms from carbon credit transactions. Indonesia and the Philippines, as regional peers, exhibit similarities with Vietnam in their REDD+ pathways and have also started to address carbon rights issues, although their frameworks are still being perfected. These case studies aim to provide comparative insights into policy development, implementation strategies, and lessons that are relevant to Vietnam’s advancement in carbon governance.

The comparison table illustrates substantial variations in forest area, cover, types, and ownership models across different countries. Brazil and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) possess the largest forest areas, with Brazil covering 497 million hectares and the DRC 154 million hectares, primarily characterized by tropical rainforests. In contrast, New Zealand and the Philippines have smaller forest extents, but New Zealand boasts a relatively high forest cover (31%), while the Philippines has only 23.3%. Unlike other countries Sweden has the biggest ratio of private forests (86%) of total forests accounting 28 million hectares. Australia and Indonesia display similar forest types, such as rainforests, mangroves, and dry forests, yet their ownership models vary significantly—Australia’s system is more balanced (76% national, 24% private), whereas the majority of Indonesia’s forests are nationally owned (85%). Vietnam’s forest governance shows a composite structure, with 68% under national control and 32% privately owned, closely resembling Indonesia’s system. This data highlights how forest policies and land tenure systems differ globally, and these differences influence conservation efforts, carbon rights, and sustainable forest management.

Table 3 shows significant variation in the governance of carbon rights across countries, reflecting divergences in legal frameworks, ownership models, and market engagement mechanisms. In Australia and New Zealand, carbon rights are well-defined and associated with private ownership, which facilitates robust participation in carbon markets. The Carbon Farming Initiative in Australia links carbon rights to land tenure and prioritizes project registration and permanence obligations to ensure accountability in emissions offset activities. Similarly, New Zealand recognizes carbon rights as separate property rights under the Carbon Rights Legislation Amendment Act (1998), allowing forest owners to sell carbon credits independently of land ownership and fostering a transparent and flexible market [

33].

Indonesia, along with other Global South countries, faces challenges in regulating carbon rights to ensure equitable benefit-sharing for its citizens. Approximately 9.2 million families reside in forest areas, of whom 1.7 million are categorized as impoverished [

34]. Although regulations allow the transfer of carbon rights, the national carbon market is underdeveloped and heavily regulated, creating uncertainties for businesses. This model benefits the government but raises concerns about marginalized communities that lack legal ownership of forest areas. The current regulations position the state as the principal owner of carbon commodities in Indonesia, granting licenses to third parties, including communities. Although Presidential Regulation No. 98/2021 permits the transfer of carbon rights within carbon trading mechanisms, the national carbon market remains underdeveloped [

35,

36].

Conversely, in Brazil, carbon rights are classified into two categories: non-tradable UREDDs for non-compensatory benefits and tradable CREDDs for offsetting emissions or facilitating international trade. This system demands rigorous proof of land ownership and project permanence, including explicit benefit-sharing mechanisms for Indigenous communities hosting REDD+ projects. Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) implement centralized models, where governments retain primary ownership of carbon rights. In Indonesia, although rights can be transferred to third parties through licenses, the market remains underdeveloped due to complex regulations and limited private sector engagement. Similarly, the DRC’s Homologation Decree facilitates rights transfers through certification, though centralized control might restrict equitable participation [

37].

In January 2020, the Government of Sweden’s inquiry on negative emissions submitted its report on enhancing carbon sinks and related incentives, while a separate forest inquiry was launched to explore protection measures, compensation, and alignment with international biodiversity commitments and a circular bioeconomy (1). In Sweden, voluntary set-asides (VSAs) allow private forest owners to conserve parts of their productive forests, reflecting a policy approach based on “freedom with responsibility”. While the government provides oversight and guidelines to ensure alignment with national environmental goals, the specific conservation measures are determined by the forest owners [

38].

In the Philippines, carbon rights are linked to natural resource rights, empowering Indigenous Peoples to retain rights over ancestral domains and benefit from revenue-sharing mechanisms. This inclusive approach ensures that carbon rights contribute to both environmental and societal objectives. These variations underscore how governance models influence the effectiveness and equity of carbon rights frameworks [

39]. Countries with decentralized or community-inclusive models, such as Australia, New Zealand, Sweden and the Philippines, generally promote broader participation, whereas centralized approaches in Brazil, Indonesia, and the DRC focus on state control but can encounter difficulties in equitable benefit-sharing and stakeholder involvement.

In principle, REDD+ or PFES could provide a pathway to local empowerment and poverty reduction. Nevertheless, additional exploration into the mechanisms required to ensure effective reach to individuals whose livelihoods depend on the forest is necessary. Effective benefit sharing guarantees fair revenue distribution and local community development, enhancing project success and allowing project developers to exhibit high integrity—meeting demand at the premium end of the market. Africa is uniquely positioned to deliver high-impact carbon projects with robust social benefits. Effective benefit-sharing mechanisms (BSMs) are crucial to this success, ensuring community direct participation and prosperity. While maintaining high-integrity standards is important, a strategic approach that customizes BSMs to local conditions can distinguish African projects in a competitive market, attracting a premium due to their significant social impact [

36].

In general, Viet Nam can learn from the experiences of pioneer countries. Carbon rights can be linked with natural resource rights and leveraged to strengthen the Payment for Forest Environmental Services (PFES) system to support ethnic minority communities, as seen in countries like the Philippines and Brazil. At the same time, Viet Nam may consider prioritizing the recognition of carbon rights as national property, following examples from Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. However, to promote private sector engagement, Viet Nam should adopt a “freedom with responsibility” approach, accompanied by the development of centralized tools for carbon accounting, management, and trading systems, as implemented in Australia, New Zealand, and Sweden. It is not strictly necessary to establish independent carbon certification bodies; instead, a certification authority could be created within the public administration system and managed at the ministerial level. These lessons can enable Viet Nam to effectively manage its natural resources while also formulating sustainable carbon policies.

3.2.4. Role of Carbon Rights in Vietnam’s Climate Commitments

By conducting a survey to develop the carbon rights policy, the respondent’s answer on the important of carbon rights is showed in

Table 4.

Through a survey questionnaire, respondents emphasized the importance of carbon rights in both sharing the outcomes of REDD+ and carbon projects and in fulfilling Vietnam’s climate commitments. Among local government participants, (73.33 ± 23.33) responded “Very important”, representing the highest percentage, followed by central government participants at (70.59 ± 20.59) as listed in

Table 2. Both local and central government respondents demonstrated high levels of agreement, with percentages exceeding 70%. In contrast, researchers show more fragmented results (42.86 ± 7.14) vs. (57.14 ± 7.14) “Agree”, and NGOs display a pattern that includes a significant proportion of “Disagree” (13.33 ± 20.00). These findings demonstrate that government agencies consider carbon rights pivotal for Vietnam’s climate commitments. Identifying carbon rights is increasingly viewed as crucial for subsequent actions and the formulation of long-term strategic climate plans in Vietnam. Overall, these results highlight the necessity of customizing policy strategies to each stakeholder group’s perspective, while accounting for the variability inherent in these survey estimates.

Table 5 reveals that, among the various perceived challenges to policy formulation and implementation, “lack of policy framework for carbon” is the most frequently cited concern, with an overall response rate of (34.43 ± 14.43), although the significance of this issue varies considerably by stakeholder group. Local Government respondents, for instance, are the most likely to emphasize both the absence of a carbon policy framework (46.67 ± 13.34) and knowledge gaps (40.00 ± 6.67), suggesting that subnational authorities may feel particularly under resourced in addressing climate-related mandates. Researchers also emphasize insufficient policy frameworks (42.86 ± 22.86), though with greater variability in responses, indicating a broader diversity of views within the academic sector. NGOs, meanwhile, distribute their concerns more evenly across various categories (e.g., lack of policy framework, lack of knowledge, and limitations in state management), reflecting moderate uncertainty or heterogeneity within that group. Central Government respondents express lower, yet still significant concerns about policy gaps and state-management constraints (23.53 ± 3.53) in each category. These patterns, along with the standard errors, underscore the multifaceted nature of policy-related challenges as perceived by each stakeholder group. In practice, these insights point to the need for more coherent policy design, enhanced knowledge transfer, and improved governance structures that are specifically tailored to each sector’s unique challenges and priorities.

Local Communities and Indigenous peoples, as primary beneficiaries of carbon credit payments, depend directly on forests for their livelihood and resource extraction. However, their voices have not been adequately considered in the policymaking process. Enhancing their role in developing carbon rights and benefit-sharing mechanisms is crucial for ensuring equitable and inclusive governance. According to survey results, a majority of participants believe local communities and Iindigenous peoples are engaged in decisions concerning carbon rights. Specifically, (50.82 ± 17.49) strongly agreed, while (45.90 ± 12.57) agreed. A very small proportion (3.28 ± 30.05) disagreed, and no participants strongly disagreed as indicated in

Table 6. These results indicate strong positive consensus across all stakeholder groups, with “Strongly Agree” and “Agree” collectively accounting for the vast majority of responses. NGOs and Local Government both show 60.00% “Strongly Agree”, alongside 33.33% and 40.00% “Agree”, respectively, suggesting a generally robust endorsement of the issue among these groups. Researchers are evenly split between “Strongly Agree” and “Agree” both (50.00 ± 0.00). Central Government displays a moderate skew toward “Agree” (58.82 ± 25.49) over “Strongly Agree” (35.29 ± 1.96), with a small result (5.88 ± 27.45) expressing disagreement. Notably, there are no “Strongly Disagree” responses reported. Overall, the data underscore that, despite some variability, most stakeholders view the policy or measure favorably, underscoring a broad base of support with minimal opposition across sectors.

3.2.5. Legal Alignment for Carbon Rights Policies

The development of forest carbon credit projects presents a significant opportunity for Vietnam’s forest protection and management units, particularly due to high market demand [

39]. Additionally, forest carbon credits frequently command higher prices than other credit types. According to 2019 data, the average price of a REDD+ credit was

$3.79 per credit, while credits from afforestation and vegetation regeneration projects averaged

$7.89 per credit [

40].

Vietnam’s Project on Emission Reduction in the North Central Region (2018–2025), covering six provinces, aims to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 32.09 million tons of CO2 equivalent. The Forest Carbon Partnership Fund (FCPF) has committed to purchasing 10.3 million tons at $5 per credit. Moreover, reports from Ecosystem Marketplace forecast a significant rise in forest carbon credit prices, driven by increased demand from private sector entities.

Participating in both compulsory and voluntary carbon markets offers multiple financial opportunities for Vietnam’s forestry sector. In particular, voluntary markets provide flexibility in developing mechanisms and policies, facilitating the sale of higher-priced carbon credits. To build a robust carbon market, this study identifies three key legal alignments: (1) carbon rights identification, (2) carbon transfer mechanisms, and (3) the simultaneous development of domestic and international carbon markets. These strategies are detailed in

Table 7.

Many countries adopt the second approach, viewing Carbon Rights as National Property, as listed in

Table 7 This model links carbon rights to national property under state administration, emphasizing autonomy and integrating mechanisms for benefit-sharing. For Vietnam, applying this model necessitates clear legal definitions, enhanced technical and financial capacities, and comprehensive cost assessments to avert conflicts [

31].

It is crucial to acknowledge that while each policy measure can address multiple barriers, no single policy can resolve all challenges comprehensively. The involvement of diverse actors, technologies, and sectors mandates the careful design, enforcement, and regular updates of policies.

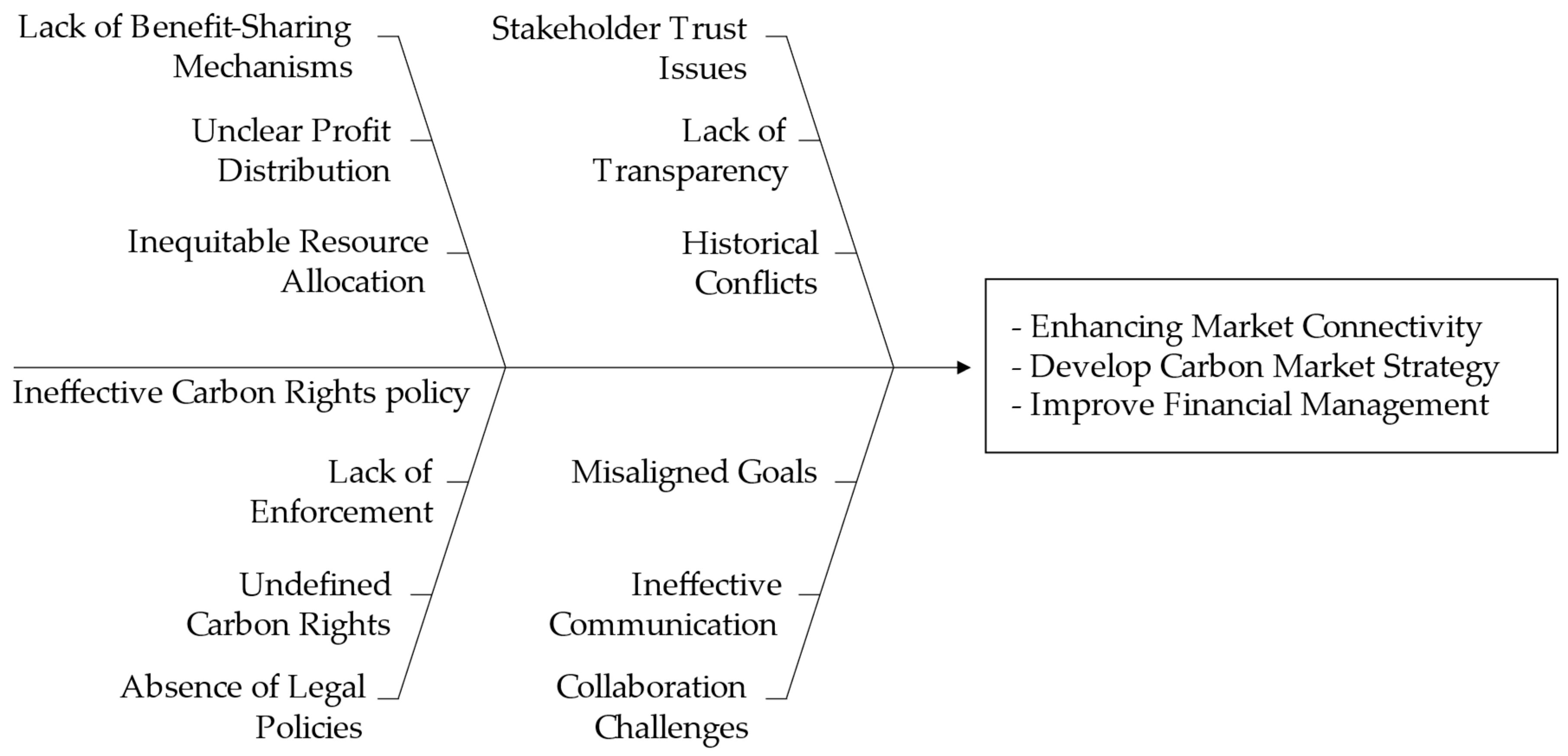

Figure 3 illustrates the procedural recommendations for policymakers and stakeholders involved in the formulation, enactment, and revision of carbon rights policies.