1. Introduction

Forest parks have evolved as significant natural and recreational spaces, contributing to both ecological conservation and human well-being. Historically, the establishment of forest parks was driven by the need to preserve biodiversity and provide controlled public access to natural landscapes [

1,

2]. Many countries have designated forest parks to balance conservation with recreation, ensuring that visitors can experience nature while minimizing environmental degradation [

3]. Over the past few decades, the expansion of protected areas and eco-tourism initiatives has led to a steady increase in forest park visitation worldwide [

4].

Forest parks play a critical role in global sustainability by maintaining ecosystem functions, preserving biodiversity, and serving as carbon sinks [

5]. They also provide cultural, aesthetic, and psychological benefits, contributing to public health and well-being [

6]. Beyond their ecological significance, forest parks serve as important economic assets, supporting local economies through tourism, employment, and community-based conservation initiatives [

6,

7,

8].

Tourism in forest parks has become an essential component of sustainable development strategies, fostering environmental awareness and financial support for conservation efforts [

9,

10,

11]. The tourist potential of forests is determined by various factors, such as the forest’s age, habitat moisture, terrain slope, stand density, the presence of undergrowth and underbrush, soil coverage, and species composition [

12]. Nature-based tourism, including activities such as hiking, wildlife observation, and camping, enhances visitors’ appreciation of natural landscapes and promotes responsible environmental behavior [

13,

14]. Studies have indicated that well-managed tourism in forest parks can contribute significantly to local and national economies while ensuring the protection of natural resources [

15,

16]. In some forest parks, tourism has surpassed the carrying capacity, leading to environmental protection issues, as observed in HengTou Mountain National Forest Park in northeast China [

17]. A similar situation has occurred in Mount Rinjani National Park and Lombok Island and other forest parks [

18,

19,

20]. One potential solution to this issue is the implementation of tourist restrictions, as seen in the Five Mountains of China and Yellowstone National Park in the USA. Some forest parks face the opposite challenge, where the number of tourists is insufficient to support the tourism services offered, leading to concerns about the sustainability of these parks [

21]. Zhou et al. found that government economic support alone cannot sustain the development of Qiandao Lake National Forest Park, China, while tourism revenue is an important economic supplement, and the relaxation and health benefits for tourists can increase their willingness to pay more [

22]. Zhang et al. indicated that competition among urban forest parks is intensifying, and improving tourist satisfaction, which enhances their likelihood of revisiting, is key to promoting the growth of forest tourism [

23]. Therefore, the challenge remains in improving visitor loyalty to increase repeat visits and recommendations for attracting more tourists in most forest parks [

24,

25,

26].

With the increasing demand for recreational opportunities in natural settings, understanding how to enhance tourist loyalty has become a critical issue for park management [

27,

28,

29]. Tourist loyalty, which represents repeat visits and recommendations, is essential in sustaining a stable long-term market and advancing sustainable development of forest parks [

27,

30].

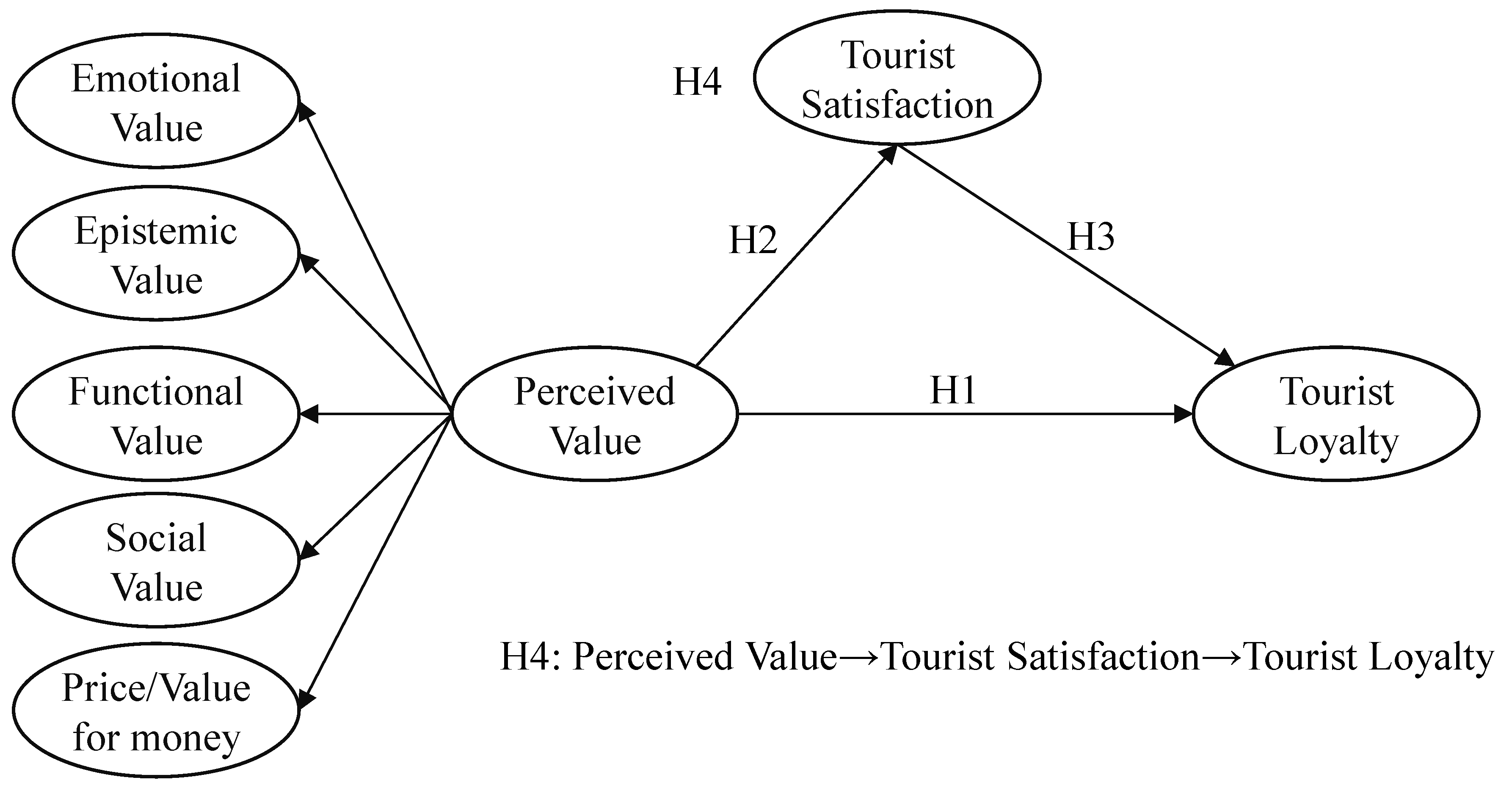

Extensive research has been conducted on the factors influencing tourist loyalty across various tourism contexts. One of the most critical determinants of tourist loyalty is perceived value, which encompasses multiple dimensions, including emotional, functional, epistemic, social, and monetary value [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Each of these dimensions shapes tourists’ overall experiences and their likelihood of revisiting or recommending the park. Studies have shown that perceived value influences tourist satisfaction and loyalty positively [

27,

37]. Different dimensions of perceived value, including functional, emotional, and social value, exhibit varying effects on tourist loyalty and satisfaction, depending on the context [

38]. Joung & Yang et al., indicated that satisfaction serves as a mediator in the relationship between perceived value and loyalty, reinforcing the importance of visitor contentment in loyalty formation [

39,

40,

41].

Despite the extensive literature on perceived value and tourist loyalty, several critical research gaps persist. While much of the existing research focuses on urban tourism, heritage sites, and hospitality, there is a paucity of studies examining tourist loyalty in nature-based tourism settings, such as forest parks [

8,

13,

28,

42,

43]. Traditional statistical methods, such as SEM and regression analysis, primarily examine linear relationships but fail to capture synergistic interactions among multiple value dimensions that influence tourist loyalty [

44]. The relative importance of different perceived value dimensions remains context-dependent, necessitating further exploration in the specific setting of forest parks [

43]. While satisfaction has been recognized as a mediator in tourism research, its specific role in the perceived value-loyalty relationship within forest parks requires further empirical validation [

8].

While perceived value has been widely acknowledged in tourism research, the precise mechanisms through which it influences tourist loyalty, particularly in forest park settings, remain underexplored.

To bridge these research gaps, this study will focus on answering the following questions:

- (1)

Does tourist perceived value have significant positive effects on tourist loyalty and tourist satisfaction in a National Forest Park context?

- (2)

Does tourist satisfaction have a perceived value that has significant positive impacts on tourist loyalty, and does it have a mediating role in the relationship between tourist perceived value and tourist loyalty?

- (3)

What are the key factors and combinations to improve tourist loyalty in a National Forest Park context?

By integrating Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with Fuzzy Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (FsQCA), this study seeks to advance theoretical understanding while providing evidence-based strategies to enhance tourist loyalty in forest parks. The insights will be valuable to park administrators, policymakers, and tourism stakeholders aiming to foster more engaging and sustainable visitor experiences. These findings will be crucial in the development of targeted strategies to improve visitor satisfaction and loyalty, ultimately contributing to the sustainability of forest parks and enriching the overall visitor experience.

The remainder of our study is organized as follows. In

Section 2, the literature on tourist perceived value, satisfaction, and tourist loyalty is explored. Then the hypotheses and the conceptual model are presented. In

Section 3, the research site is firstly introduced, and then the measurement instrument and data collection process are demonstrated. The data summary is then presented. In

Section 4, the measurement model is firstly tested, and then the hypotheses are examined. The configuration analysis to improve tourist satisfaction and loyalty is then conducted with fuzzy set quantitative comparative analysis (FsQCA). At last, the results are discussed, and the limitations and further research are highlighted in

Section 5.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Site: Yingde National Forest Park

Yingde National Forest Park, situated in Yingde City, northern Guangdong Province, China, is a prime example of a protected natural area that combines ecological conservation with sustainable tourism. Established in 2000, it is one of the earliest and the biggest national forest parks in Guangdong Province. The park, renowned for its rich biodiversity, scenic landscapes, and unique cultural heritage, plays an essential role in both environmental protection and the local economy.

Yingde National Forest Park spans over 50,000 hectares of lush forest, characterized by a variety of plant species and diverse ecosystems. The park is a critical habitat for numerous endemic species, including several that are under threat of extinction. The forest functions as a vital carbon sink, contributing to the region’s efforts in mitigating the impacts of climate change. In addition, the park’s unique geographical features, such as its steep mountains, deep valleys, and crystal-clear streams, contribute to the region’s ecological balance.

In recent years, the tourism industry in Yingde has been promoted as a way to boost local economic development while preserving the region’s natural beauty. The park offers a range of activities designed to provide visitors with a deeper connection to nature, including hiking, wildlife observation, and photography. It also features educational programs aimed at raising awareness about environmental conservation and the importance of protecting natural habitats.

Yingde National Forest Park has become a popular destination for eco-tourism, drawing visitors from the Great Bay Areas. The integration of sustainable tourism practices ensures that tourism activities contribute to the local economy without compromising the park’s ecological integrity.

Despite its success in environmental protection, Yingde National Forest Park faces challenges in competing with other national forest parks and rural tourist spots. Additionally, there is the issue of tourism product renewal, which can lead to the degradation of tourism development over time. One of the primary concerns is how to increase tourist loyalty to ensure higher rates of revisiting and recommendations. This challenge has become a major problem for the park, as sustained visitor engagement is crucial for long-term success. Studying how to improve tourist loyalty is therefore critical for the sustainable tourism development of the park and for contributing to the local economic development.

3.2. Measurement Instrument

The initial phase of the research involved designing a questionnaire, guided by Churchill’s scale development procedures [

62]. The questionnaire was structured into two primary sections. The first section focused on collecting demographic data, including age, gender, education level, and economic status. The second section measured key variables, such as tourist perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty.

Tourists’ perceived value was evaluated using the five-dimension scale developed by Sheth et al. [

46] and adapted with the advice of Schneider & Wagemann [

60]. The adapted scale encompassed five dimensions, including emotional value (EV), epistemic value (EpV), social value (SV), functional value (FV), and price/value for money (PVM). Tourist satisfaction was assessed through the whole satisfaction between the gap of tourist expectation and perceived performance developed by Oliver [

56], comprising four items. Tourist loyalty was measured using the scale developed by Oppermann [

53], which included three components: intention to revisit, recommend, and pay more. The scale was shown in

Table 1. All rating variables were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 represented “completely disagree” and 5 indicated “completely agree”.

3.3. Data Collection

The study utilized convenience sampling to collect data from visitors at Yingde National Forest Park. This approach was chosen due to the lack of a defined tourist population or a comprehensive visitor list for random sampling [

63,

64]. It also proved friendly for both researchers and participants.

Data were collected through a questionnaire-based survey conducted on weekends and public holidays between 1 May and 31 October 2024. To mitigate potential sample selection bias inherent in convenience sampling, data were collected from 11 distinct tourist clusters within the park. Additionally, different questionnaire distributors were assigned to collect data at various locations during each survey session. With approval from park management, four trained graduate students administered the questionnaires on-site. Visitors were invited to participate in the survey about their park experience, with a small gift offered as an incentive. In alignment with related studies on tourist loyalty, no strict distinction was made between first-time and repeat visitors [

28,

65,

66]. Questionnaires were distributed to consenting participants during their rest or visit periods [

63].

Of the 436 questionnaires collected, 32 were excluded due to missing values, resulting in 404 valid responses and a validity rate of 91.07%. The sample comprised 54.20% male and 45.80% female respondents. By age, 26.50% were under 18, 25.20% were 19–35 years old, 25.50% were 36–60, and 22.80% were over 60. Educationally, 62.60% held a university degree. In terms of annual income, 59.30% earned between 60,000 and 200,000 Yuan RMB, while 23.80% earned above 200,000 Yuan RMB. A summary of these items is provided in

Table 1.

3.4. Research Methods

Initially, the data was assessed for normality with the descriptive analysis of SPSS (v26.0), and the common method bias was evaluated with the single-factor test analysis of SPSS. The research hypotheses were subsequently tested using a two-stage approach, as recommended by Hair et al. [

67]. In the first stage, a measurement model was developed using CB-SEM (Covariance-Based SEM) to evaluate validity and reliability. In the second stage, a structural model was applied to test the research hypotheses. At last, the configuration analysis was conducted using the FsQCA model to identify the potential path to increasing tourist loyalty [

68].

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Research Conclusions

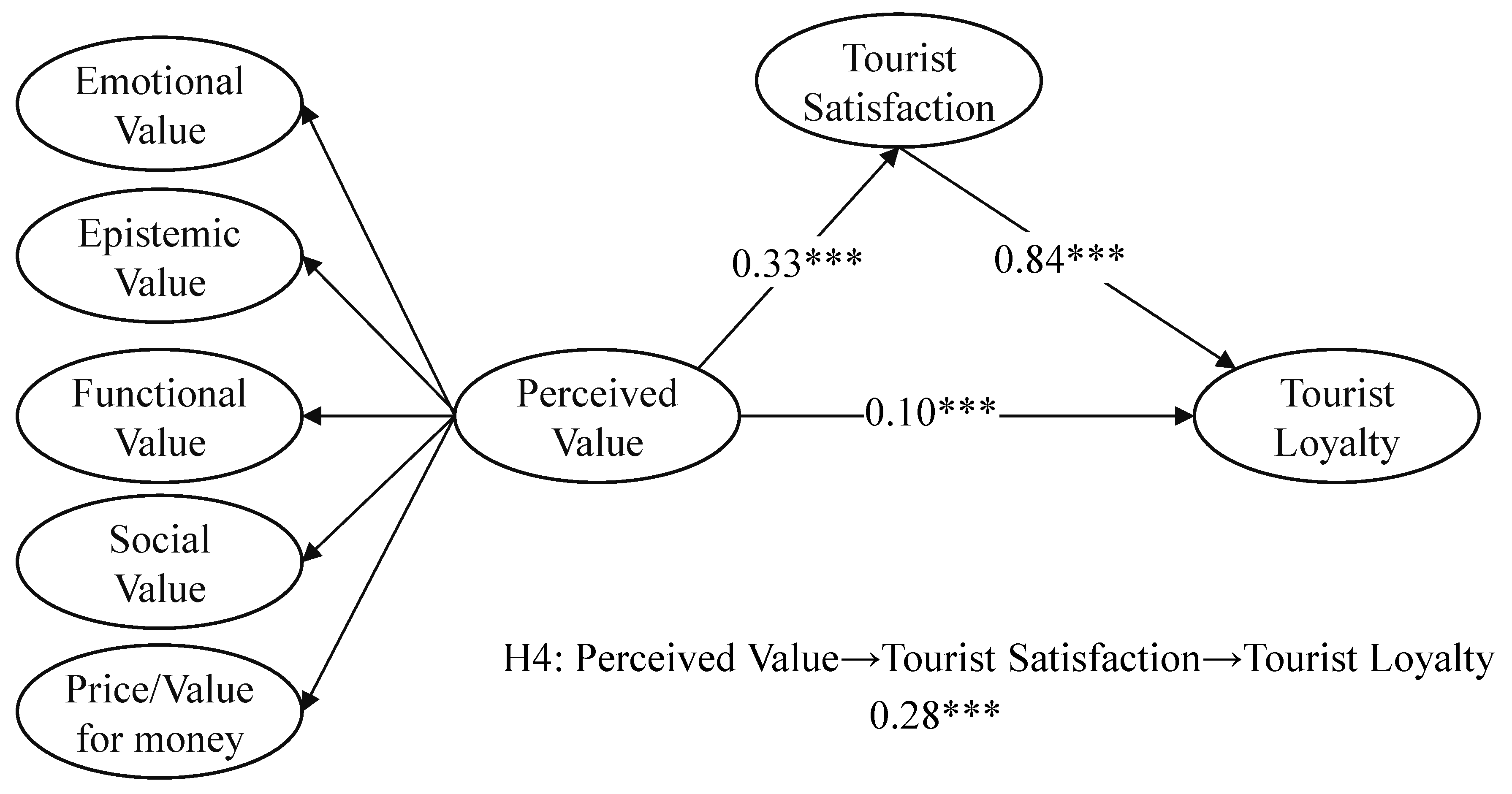

The covariance-based SEM and fsQCA methods were employed to reveal that perceived emotional value, epistemic value, functional value, social value, and price/value for money jointly influence tourist satisfaction and loyalty in forest parks. The following conclusions are drawn.

First, tourist perceived value in forest parks can be represented with emotional value, epistemic value, functional value, social value, and price/value for money significantly. The coefficients of emotional value, functional value, and social value are higher than that of epistemic value and price/value for money, indicating emotional value, functional value, and social value have greater importance in measuring tourist perceived value in forest parks.

Second, tourist perceived value has a significant positive effect on tourist loyalty and tourist satisfaction. Tourist satisfaction plays a significant positive mediating role between perceived value and tourist loyalty in forest parks. The indirect effect of tourist perceived value on tourist loyalty mediated by tourist satisfaction is higher than the direct effect. Tourist satisfaction is an important mediating variable for improving tourist loyalty in forest parks. Studies have shown that perceived value has a significant impact on tourist loyalty across various tourism sectors, including eco-tourism, forest parks, and rural tourism destinations [

4,

37,

61]. Our study aligns with these findings, confirming that perceived value plays a crucial role in shaping tourist loyalty, with satisfaction acting as a mediator in this relationship. Previous research consistently demonstrates that enhancing perceived value can lead to increased tourist satisfaction, which, in turn, fosters greater loyalty through revisit intentions and recommendations. For destination managers, this underscores the importance of improving perceived value as a key strategy to boost tourist loyalty, ensuring higher rates of repeat visitation and positive word-of-mouth.

Third, five pathways to enhancing tourist loyalty are identified with FsQCA analysis, and the five pathways can be categorized into three distinct modes: the economic value-driven model, the dual-core model driven by functional and epistemic value, and the emotional and social value-driven model. The economic value-driven model treats the cost incurred as an auxiliary variable, and the dual-core model, driven by functional and epistemic values, identifies these two variables as the core drivers, while the emotional and social value-driven model consists of three pathways, where emotional and social values serve as core drivers. The pathways indicate that the dimensions of perceived value play different roles across various pathways, with no single dimension consistently playing the most important role in enhancing tourist loyalty across all pathways.

Fourth, four primary pathways to improve tourist satisfaction were identified, and they can be categorized into two modes: the economic value-driven model and the functional value plus driven model. In the economic value-driven model, the cost is treated as an auxiliary variable, while the functional value plus driven model consists of three distinct paths, with functional value as the core driving variable. Different dimensions of perceived value play distinct roles in various pathways for improving tourist satisfaction.

5.2. Theoretical and Managerial Contribution

Firstly, we combine the five dimensions of tourist perceived value to identify pathways for improving tourist satisfaction and loyalty in forest parks, offering an innovative perspective on tourist loyalty research. Previous studies have shown that perceived value significantly affects tourist loyalty [

41,

64,

87]. However, much of the existing research has focused on the impact of a single dimension [

4] or a joint dimension [

88] of perceived value on tourist loyalty or has primarily examined the measurement of perceived value dimensions [

55], often overlooking the influence of the multi-dimensional interplay on tourist loyalty. To fill this gap, we employed fsQCA to explore the effect mechanism of emotional value, epistemic value, functional value, social value, and price/value for money on tourist loyalty. Through this analysis, we identified key factors and pathways that contribute to higher satisfaction and increased loyalty. The results provide valuable theoretical insights for the diversified management of forest parks and contribute to advancing the research on tourist loyalty by incorporating a multi-dimensional approach.

Secondly, our study demonstrates that price/value for money plays an important role in shaping higher tourist satisfaction and increasing loyalty, thereby enriching the research on perceived value. While previous research on perceived value measurement has highlighted the importance of price in tourism, our study offers new insights into this relationship. Recent studies have used structural equation modeling to confirm that price/value for money is a key factor in measuring perceived value and influencing tourist loyalty [

60]. Our findings support this by showing that price, as the only indispensable factor in the pathways, leads to higher satisfaction and increased tourist loyalty. Moreover, we identify the interaction effects of functional and epistemic value as well as emotional and social value on tourist loyalty. The combinations of functional and epistemic value and emotional and social value are key to enhancing tourist loyalty. As core factors, the combinations of emotional and social value can be further extended to three paths for improving tourist loyalty, advancing the field of configuration research on tourist loyalty.

Third, economic value (price/value for money) is an essential factor influencing both tourist satisfaction and loyalty [

60]. Therefore, forest park managers should prioritize pricing strategies that enhance economic value for tourists, such as offering family packages, parent-child tickets, group discounts, and promotional offers. These initiatives not only improve the perceived economic value but also contribute to higher tourist satisfaction and loyalty.

Fourth, the combinations of emotional and social value can be extended into three distinct pathways for enhancing tourist loyalty. It is crucial for park managers to strengthen emotional connections between tourists and the forest park, which can significantly improve loyalty. For instance, organizing high-quality, interactive activities that foster emotional engagement among visitors can stimulate emotional resonance and attachment. Additionally, enhancing the construction and quality of basic service facilities, such as hiking trails, digital infrastructure (e.g., free Wi-Fi, navigation maps), and leisure amenities within the forest park, will elevate the perceived functional value. These improvements can further boost tourist loyalty by creating a more convenient and enjoyable experience.

Fifth, both over-visitation and under-visitation contribute to the unsustainable development of national forest parks. Over-visitation leads to environmental degradation, while under-visitation results in economic challenges that undermine the parks’ sustainability. To address these issues, it is crucial to strengthen policies related to forest park management, ensuring they integrate environmental, economic, and social goals. Collaboration among relevant government agencies (e.g., forestry, tourism, and environmental departments) should be promoted to develop integrated strategies that balance park development, conservation, and sustainable tourism. Furthermore, clear metrics should be established to assess the effectiveness of forest park management and evaluate the impact of tourism. Regular policy assessments, informed by data-driven insights, are essential for making necessary adjustments and ensuring long-term sustainability.

5.3. Limitations

Our study has made a little breakthrough in perceived value and tourist loyalty in forest parks, but there are still limitations that need to be improved. First, the perceived value-satisfaction-loyalty chain model was employed to study how tourist perceived value influences loyalty and identify the pathways to improve tourist loyalty based on the combination of five dimensions of perceived value. However, this study may not identify all factors that clarify the action mechanism on higher tourist loyalty. Therefore, to extract all factors that influence tourist loyalty, identify key factors, and find combinations of key factors to improve tourist loyalty is one of the research points in the future. It is important to find the key factors of items and combinations of items to improve tourist loyalty. Second, we took Yingde National Forest Park tourists as the research sample; there are still differences about tourist spots, recreation items, and even service quality in forest parks and regions. Therefore, heterogeneity analysis of factors and pathways remains to be further explored next. Third, it is clear that the tourism experiences of different visitor groups (e.g., first-time vs. repeat visitors, weekday vs. weekend visitors, and family vs. individual visitors) vary significantly. Therefore, future research should focus on comparing the differences among these distinct visitor groups.