Measurement Errors from Successive Inventories on Concentric Circular Field Plots and Their Impact on Volume and Volume Increment in Uneven-Aged Silver Fir Stands

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Work

- Remeasured tree—A tree present in both the first and second inventories.

- (2a) New sample tree (nongrowth)—A tree that exceeded the DBH threshold of 30 or 50 cm.(2b) Reclassified sample tree—A tree incorrectly included in the first inventory due to DBH measurement error but meeting the sampling criteria in the second inventory.

- New sample tree (ingrowth)—A tree that exceeded the inventory DBH threshold of 10 cm.

- Harvested tree (thinning or selection cut)—A tree sampled in the first inventory but removed through thinning or selection cutting.

- Harvested tree (clear-cut or shelterwood cut)—A tree sampled in the first inventory but removed through clear-cutting or shelterwood cutting.

- Dead tree—A tree sampled in the first inventory that no longer exists as a living standing tree.

- Missing tree—A tree measured in the first inventory that could not be located, with no visible stump at the recorded position.

- Erroneously sampled tree (excluded)—A tree incorrectly sampled in the first inventory due to horizontal distance error and excluded from the second inventory.

- Erroneously sampled tree (included)—A tree incorrectly sampled in the first inventory due to horizontal distance error but included in the second inventory due to DBH increase.

- Previously omitted tree—A tree mistakenly excluded from the first inventory but included in the second inventory.

2.2. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

- Misidentification of adjacent trees during the second inventory.

- Gross errors in transcription, e.g., 7.5 cm instead of 75 cm.

- Illegible numbers in the field data forms—unclearly written or poorly corrected digits (usually a single digit).

- Errors in caliper readings or errors caused by miscommunication between the measurer and data recorder.

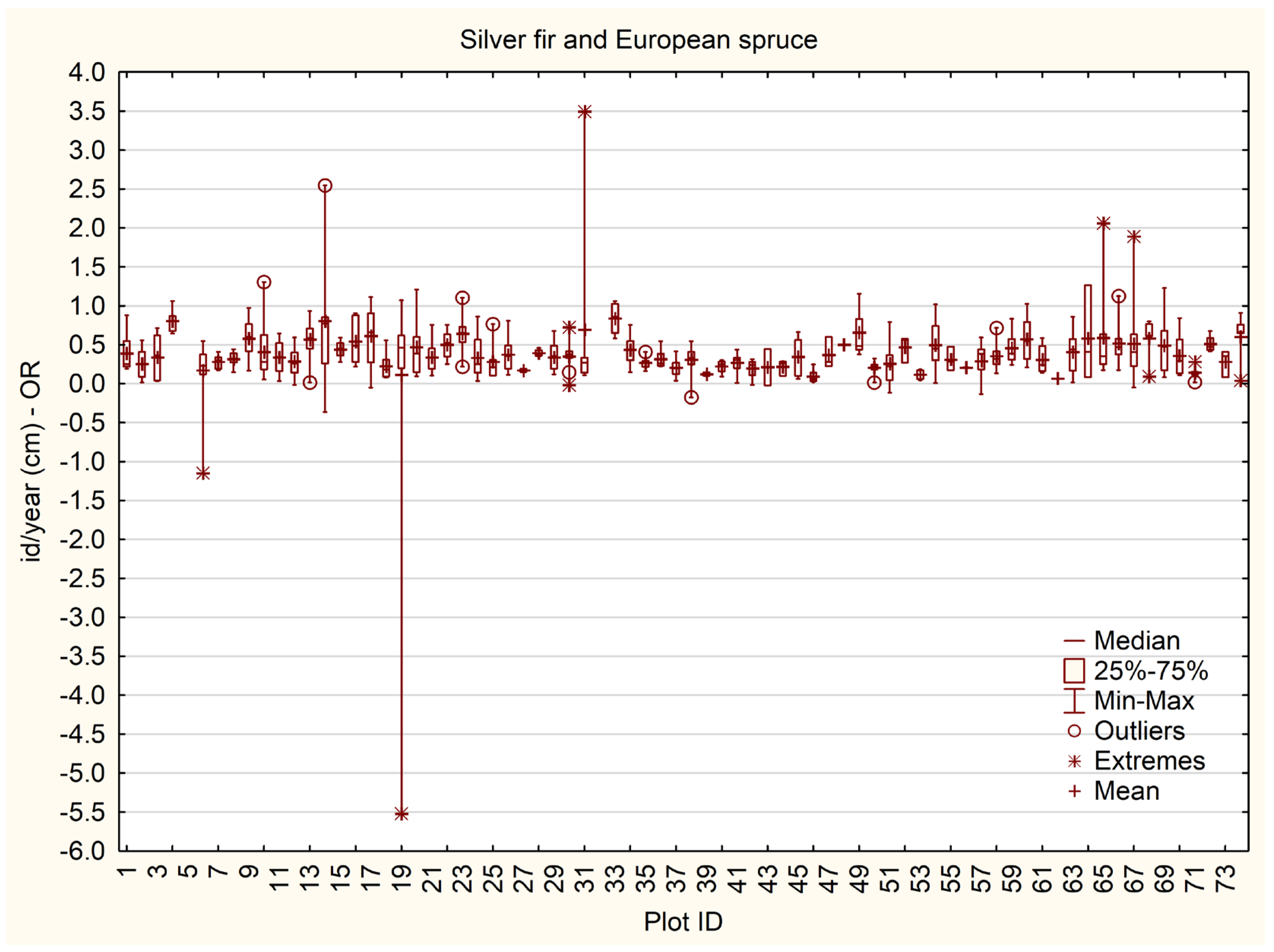

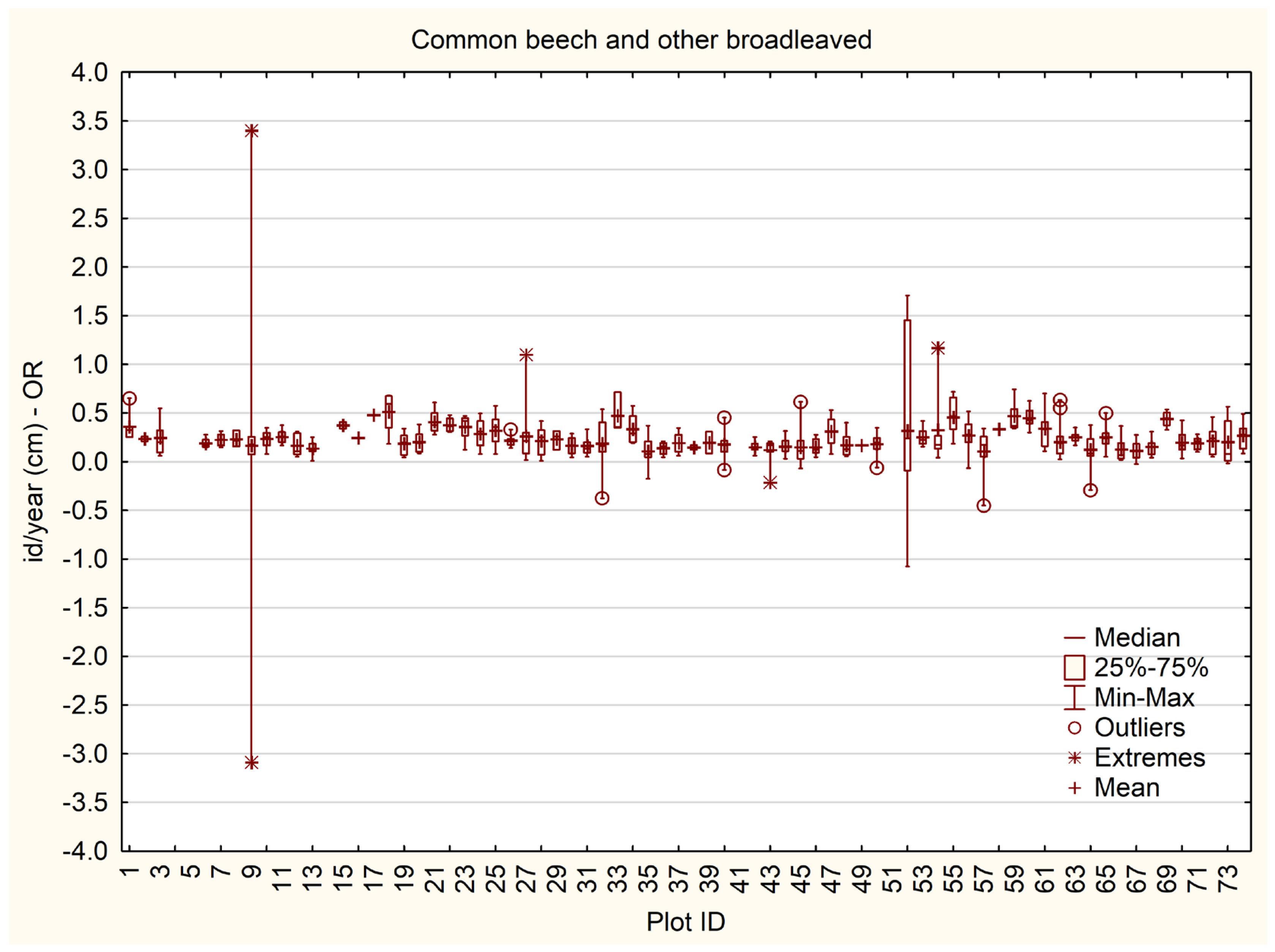

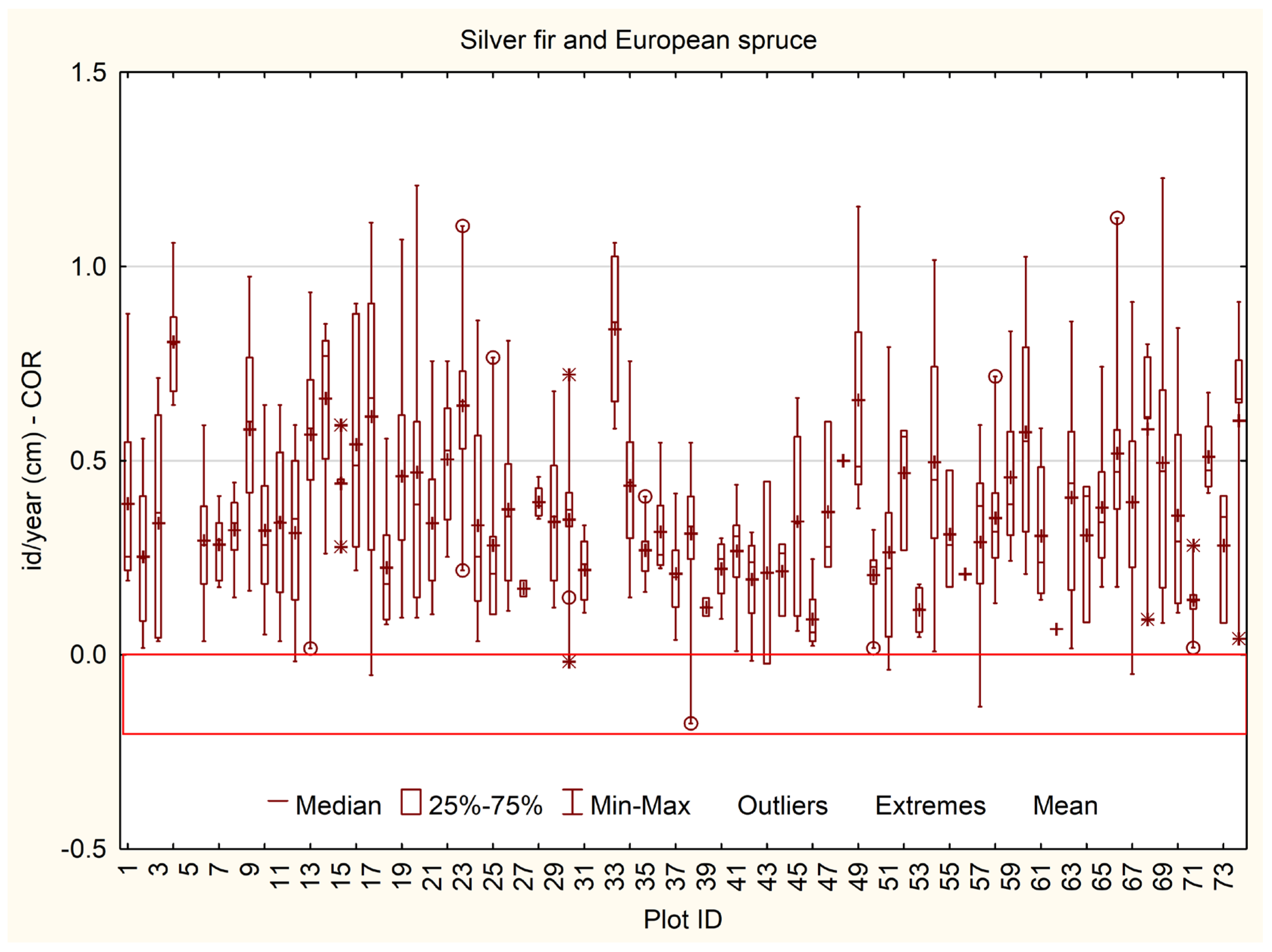

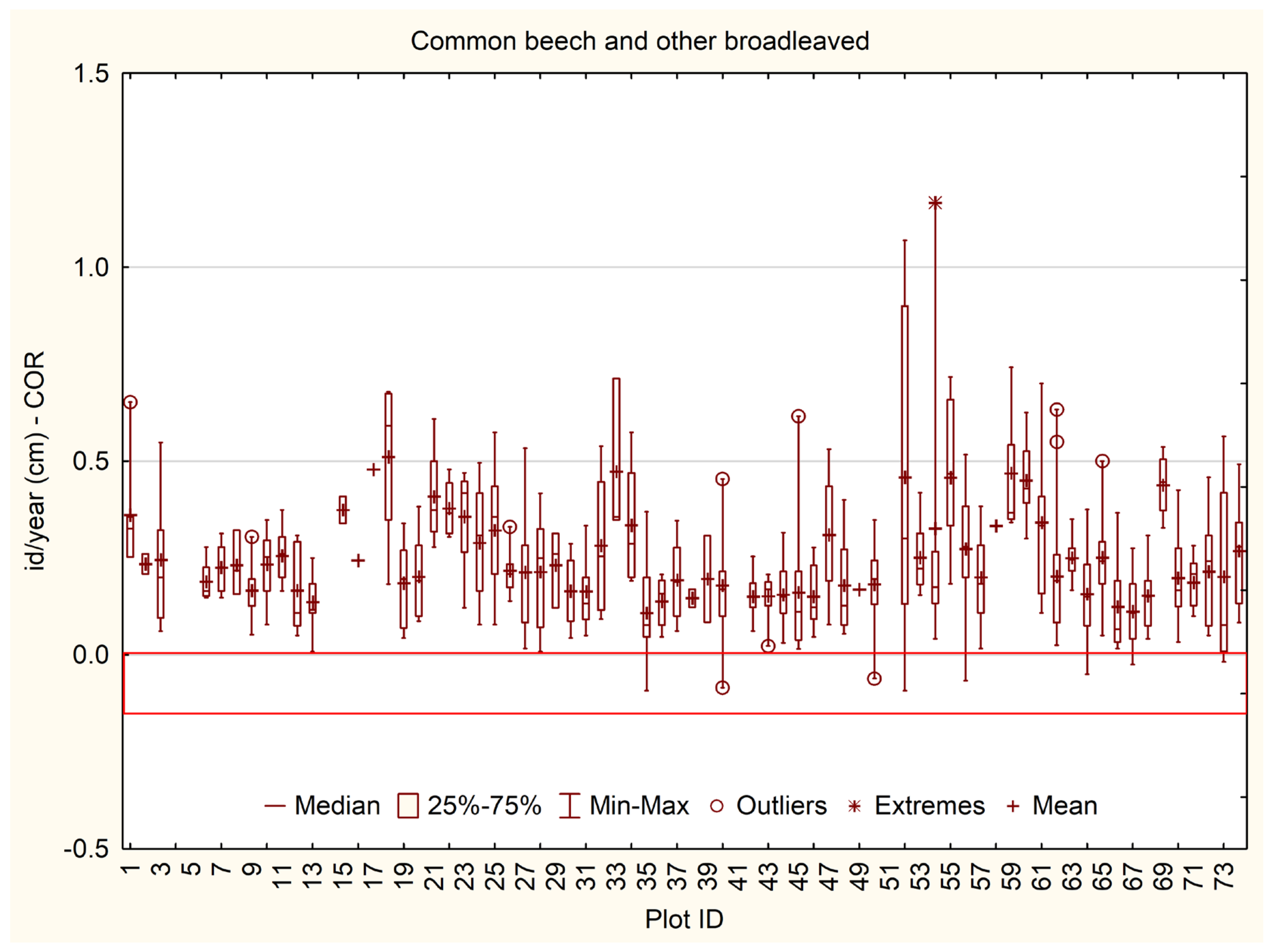

- High or low competition pressure on some plots, resulting in a below- or above-average increment of all trees on the plot, as presented in Figure 3. In these cases, data was considered as valid and retained without correction.

3.1. Impact of Measurement Errors on Volume Calculation at Tree, Plot, and Overall Level

3.1.1. Tree Level

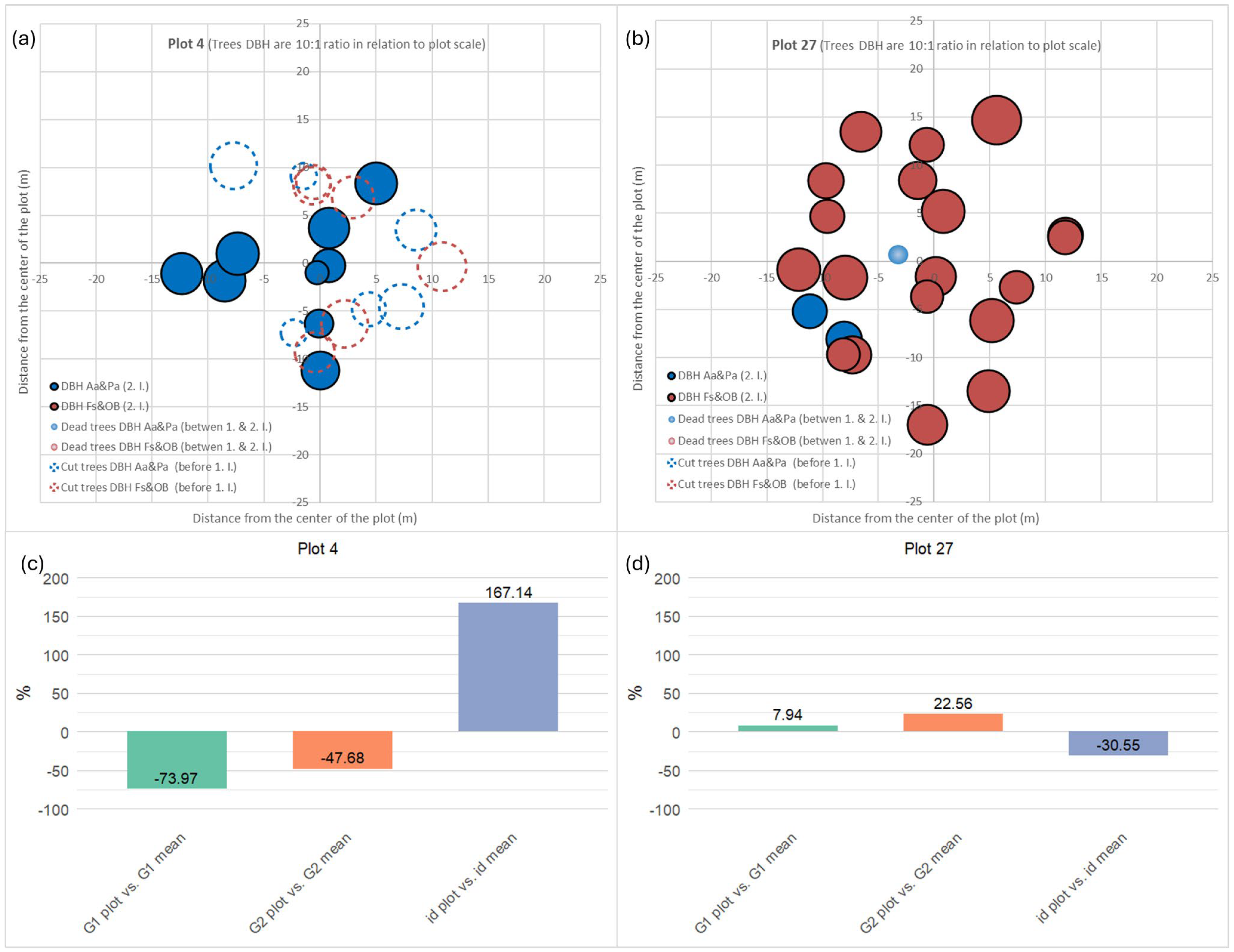

- Tree 182 (Plot 9): Due to misidentification, the DBH was corrected from 22.8 cm to 60.1 cm, increasing the estimated tree volume from 0.4 m3 to 4.2 m3. As a consequence of this DBH adjustment, the tree’s expansion factor was recalculated based on a larger plot radius, reducing its value from 65 to 8 trees per hectare. Accordingly, volume per hectare increased from 27.2 m3/ha to 33.5 m3/ha.

- Tree 199 (Plot 10): Second inventory DBH was corrected from 85.5 cm to 75.5 cm, reducing the estimated tree volume from 9.6 m3 to 7.3 m3. Since the tree expansion factor remained unchanged, the volume per hectare decreased from 76.2 m3/ha to 57.9 m3/ha.

- Tree 374 (Plot 19): Due to a gross transcription error, the DBH in the second measurement was incorrectly recorded as 7.5 cm instead of 75 cm, with correction resulting in an increase in estimated tree volume from 0.0 m3 to 8.15 m3. As a consequence of the corrected DBH, the tree expansion factor increased from 0.0 to 8.0, and the volume per hectare increased from 0.0 m3/ha to 64.88 m3/ha.

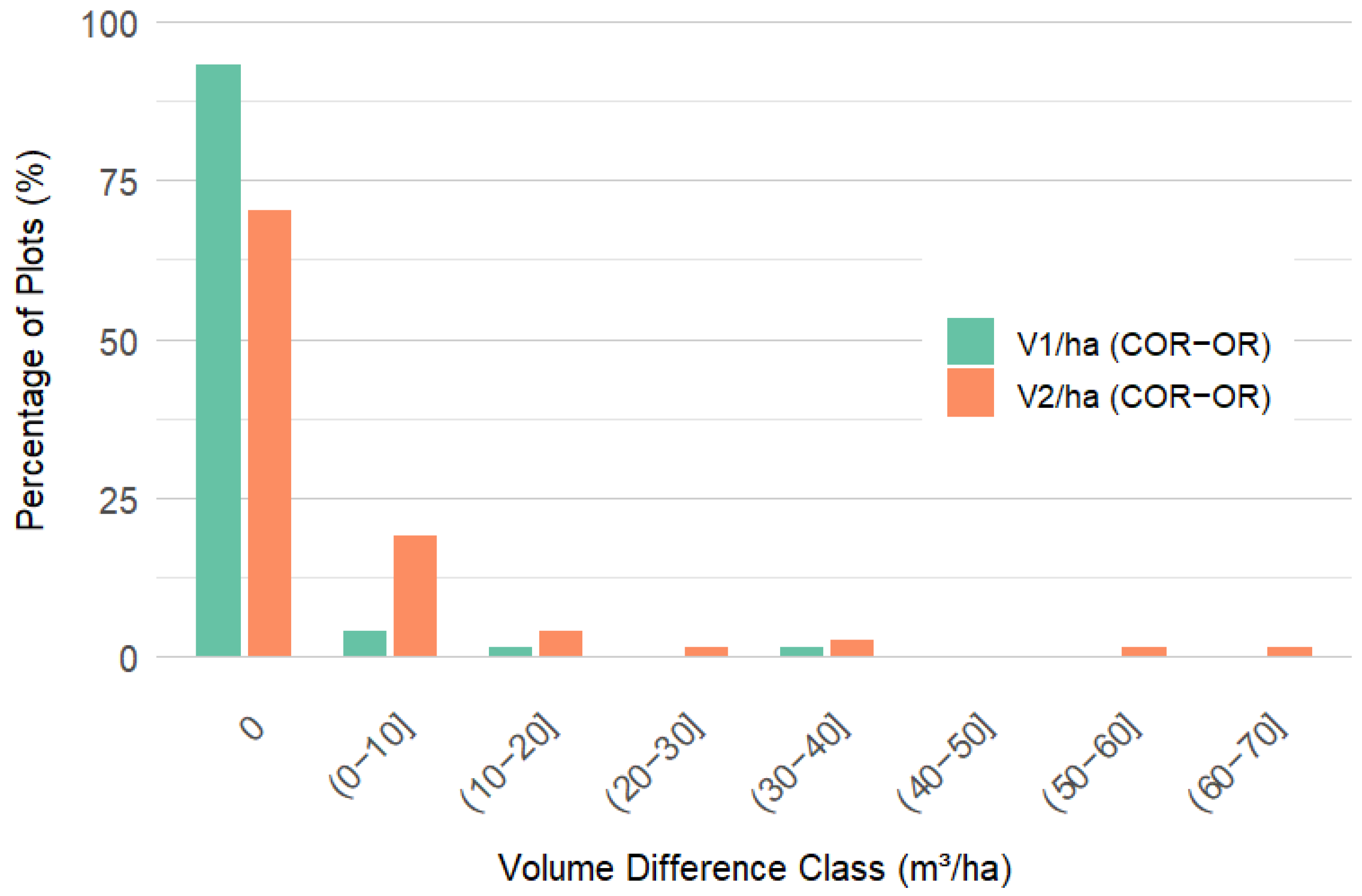

3.1.2. Plot Level

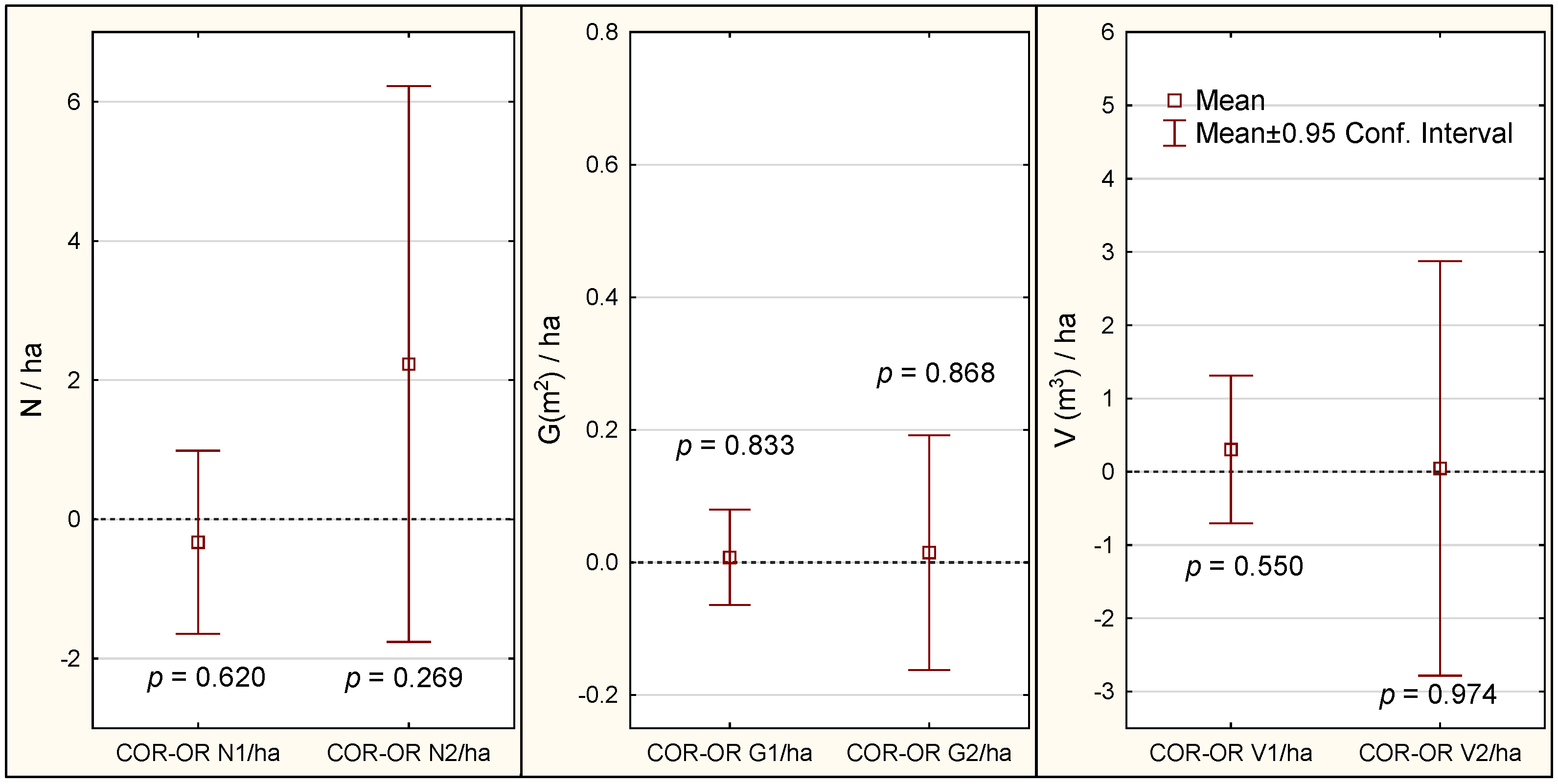

3.1.3. Overall Level

3.2. Aditionally Observed Ambiguities and Data Inconsistencies

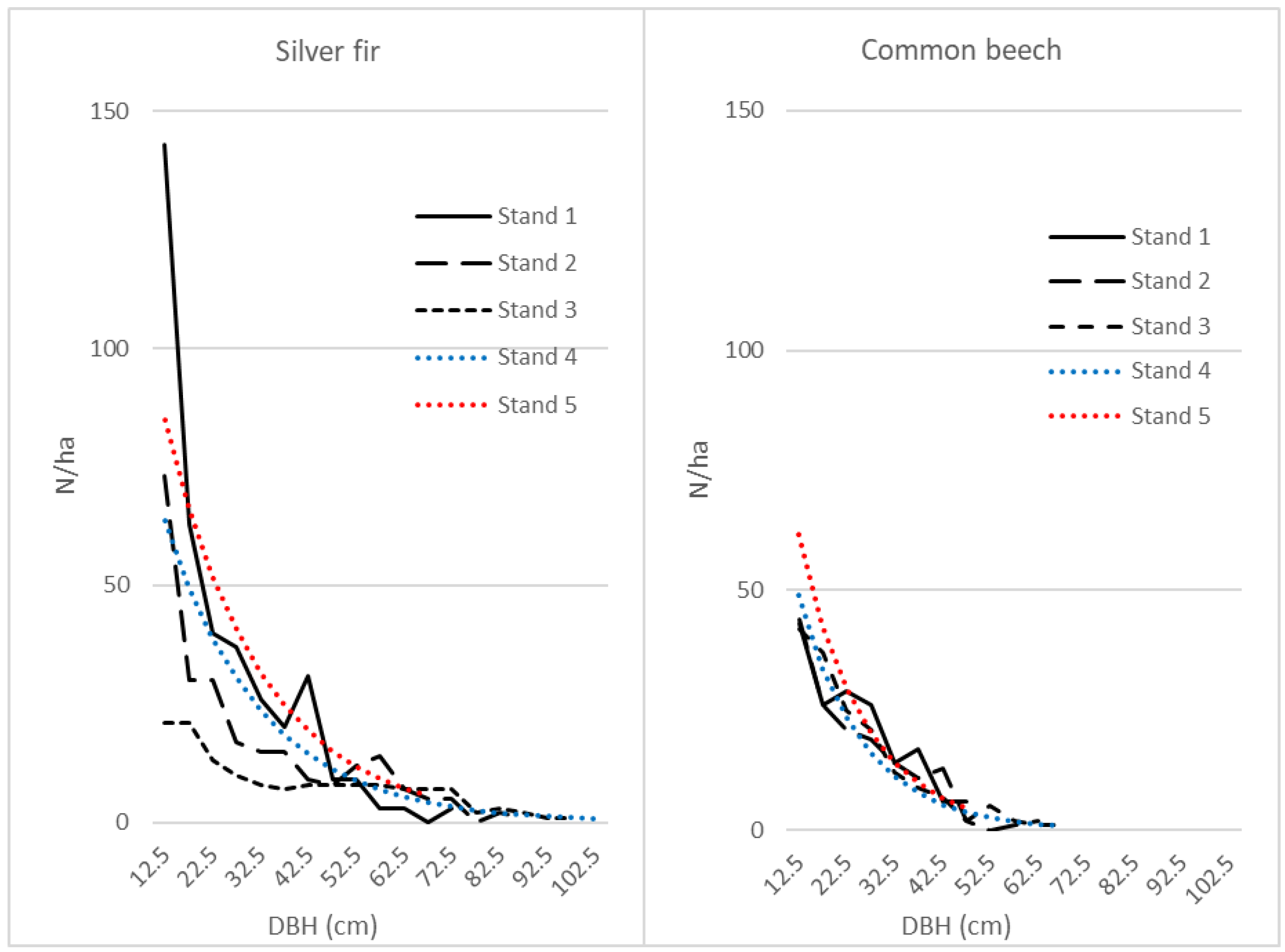

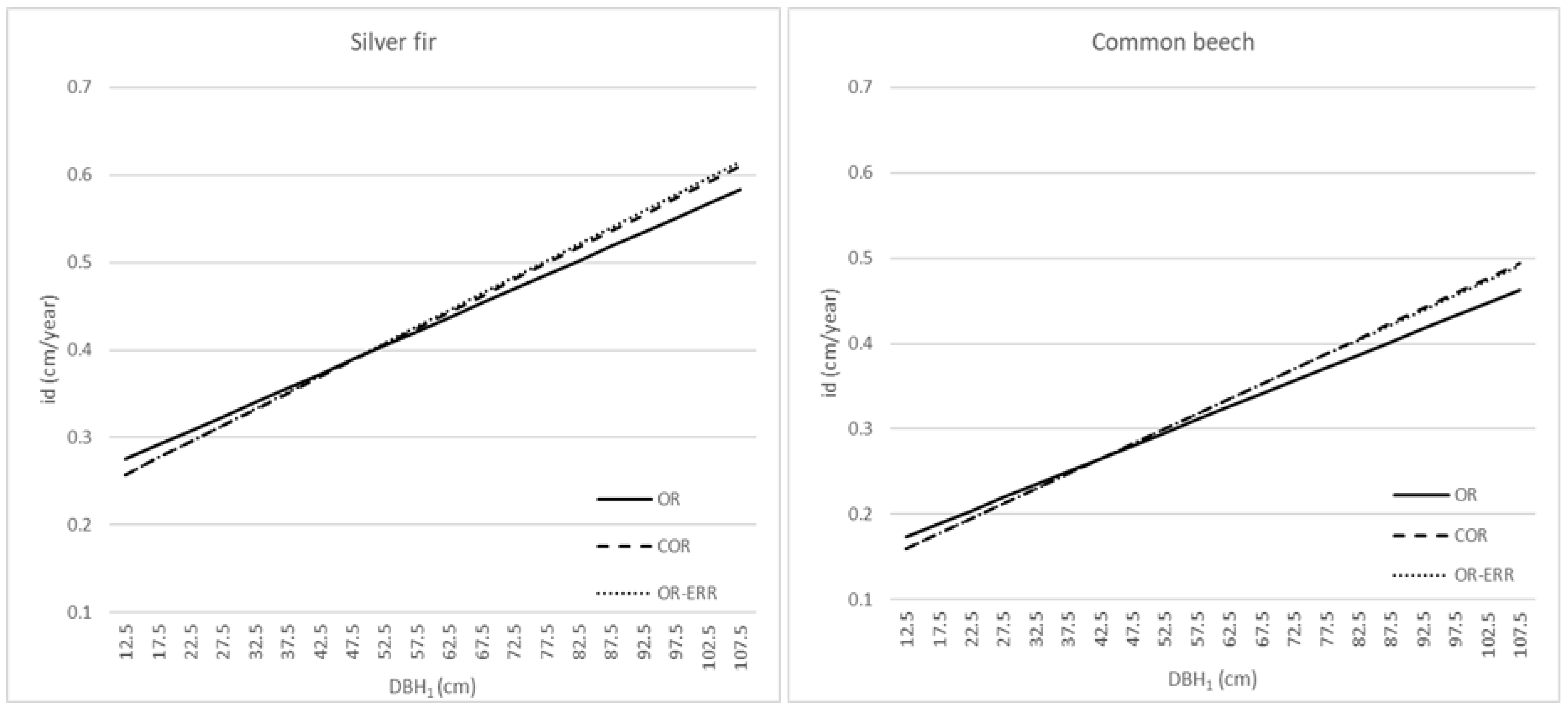

3.3. Diameter Increment Models and Volume Increment

4. Discussion

4.1. Detected Causes of Large or Impossible Increment Values for Individual Trees

4.2. Influence of Errors on Volume Calculation at Tree, Plot, and Overall Level

4.3. Aditionally Observed Ambiguities and Data Inconsistencies

4.4. Diameter Increment Models and Volume Increment

4.5. Final Remarks

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holt, M.W. Data Quality Assessment of Continuous Forest Inventory on State Forest Lands in Tennessee. Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gschwantner, T.; Lanz, A.; Vidal, C.; Tomter, S.M.; Kuliešis, A.; Rondeux, J.; Alberdi, I.; Vestmanis, R.; Lawrence, M. Comparison of methods used in European National Forest Inventories for the estimation of volume increment: Towards harmonisation. Ann. For. Sci. 2016, 73, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRoberts, R.E.; Tomppo, E.O.; Czaplewski, R.L. Sampling designs for national forest assessments. In Knowledge Reference for National Forest Assessments; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Pravilnik o Uređivanju Šuma. Narodne Novine; Croatian Parliament: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018; Issue 97. [Google Scholar]

- Schöpfer, W. Die Auswirkungen von Zuwachsbohrungen in Fichtenbeständen. Allg. Forst-und Jagdztg. 1962, 133, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Klepac, D. Rast i Prirast Šumskih Vrsta Drveća i Sastojina; Nakladni Zavod Znanje: Zagreb, Croatia, 1963; p. 144. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, P.; Tomé, M.; Skovsgaard, J.P.; Vanclay, J.K. Evaluating a growth model for forest management using continuous forest inventory data. For. Ecol. Manag. 1995, 71, 251–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, P. Application of regression analysis to inventory data with measurements on successive occasions. For. Ecol. Manag. 1995, 71, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranneby, B.; Rovainen, E. On the determination of time intervals between remeasurements of permanent plots. For. Ecol. Manag. 1995, 71, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinn, C.; Bhandari, N.; Fehrmann, L. Observations and measurements. In FAO National Forest Assessment: Field Manual for Sample-Based Inventory; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nanos, N.; Sjöstedt de Luna, S. Fitting diameter distribution models to data from forest inventories with concentric plot design. For. Syst. 2017, 26, e01S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čavlović, J.; Božić, M. Nacionalna Inventura Šuma u Hrvatskoj—Metode Terenskog Prikupljanja Podataka; Šumarski Fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu: Zagreb, Croatia, 2008; ISBN 978-953-292-007-9. [Google Scholar]

- Köhl, M.; Scott, C.T.; Zingg, A. Evaluation of permanent sample surveys for growth and yield studies: A Swiss example. For. Ecol. Manag. 1995, 71, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.L.; Arner, S.L. Estimating Previous Diameter for Ingrowth Trees on Remeasured Horizontal Point Samples; General Technical Report NE-165; USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station: Radnor, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Poso, S.; Waite, M.-L. Calculation and comparison of different permanent sample plot types. Silva Fennica 1995, 29, 5554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.T. An Overview of Fixed Versus Variable-Radius Plots for Successive Inventories; USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station: Radnor, PA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hébert, J.; Bourland, N.; Rondeux, J. Estimation de l’accroissement et de la production forestière à l’aide de placettes permanentes concentriques. Ann. For. Sci. 2005, 62, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, P.S.B.; Reams, G.A.; Smith, W.B. Forest Inventory and Analysis Fiscal Year 2017 Business Report; Forest Service FS-1131; United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Research and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, E.; Schwyzer, A. Control survey of the terrestrial inventory. In Swiss National Forest Inventory: Methods and Models of the Second Assessment; Brassel, P., Lischke, H., Eds.; Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL: Birmensdorf, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Čavlović, J. Nacionalna inventura Šuma Republike Hrvatske—Priručnik za Provedbu Druge Inventure Šuma; Ministarstvo Poljoprivrede: Zagreb, Croatia, 2017; 210p. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, R.O.; Marshall, D.D. Permanent-Plot Procedures for Silvicultural and Yield Research; General Technical Report PNW-GTR-634; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station: Portland, OR, USA, 2005; 86p. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, F.X.; Hall, F.S. Logarithmic Expression of Timber-Tree Volume. J. Agric. Res. 1933, 47, 719–734. [Google Scholar]

- Čavlović, J.; Božić, M.; Kušan, V.; Antonić, O.; Nöthig, V. Pilot inventura šumskih resursa: Testiranje idejnog i operativnog plana nacionalne inventure šumskih resursa Republike Hrvatske; Šumarski Fakultet: Zagreb, Croatia; Ministarstvo Poljoprivrede, Šumarstva i Vodnoga Gospodarstva: Zagreb, Croatia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Michailoff, I. Zahlenmässiges Verfahren für die Ausführung der Bestandeshöhenkurven. Forstwissenschaftliches Cent. Tharandter Forstl. Jahrb. 1943, 6, 273–279. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, R.P.; Vacek, Z.; Vacek, S. Nonlinear mixed effect height–diameter model for mixed species forests in the central part of the Czech Republic. J. For. Sci. 2016, 62, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Pukkala, T.; Li, F.; Dong, L.-H. Developing growth models for tree plantations using inadequate data—A case for Korean pine in Northeast China. Silva Fenn. 2019, 53, 10217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepac, D. Novi Sistem Uređivanja Prebornih Šuma; Šumarski Fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu: Zagreb, Croatia, 1961; Reprinted by Hrvatske Šume: Zagreb, Croatia, 1997; Available online: https://www.sumari.hr/biblio/pdf/10787.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Klepac, D. Novi sistem Uređivanja Prebornih Šuma (dodatak); Poljoprivredno šumarska komora SR Hrvatske: Zagreb, Croatia, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Westfall, J.A.; Patterson, P.L. Measurement variability error for estimates of volume change. Can. J. For. Res. 2007, 37, 2201–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnor, G.M.; De Jong, R.J.; Boudewyn, P.; Flewelling, J.W. Data and model validation methods used in developing the STIM growth model. Forskningsserien 1993, 3, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Magnussen, S.; Reed, D. Modelling for estimation and monitoring. In National Forest Assessments—Experiences from FAO Projects 2000–2005; FAO/IUFRO: Rome, Italy, 2004; pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Stierlin, H.R. Criteria and provisions for quality assurance. In Swiss National Forest Inventory: Methods and Models of the Second Assessment; Brassel, P., Lischke, H., Eds.; Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL: Birmensdorf, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 281–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kindermann, G.E.; Kristöfel, F.; Neumann, M.; Rössler, G.; Ledermann, T.; Schueler, S. 109 years of forest growth measurements from individual Norway spruce trees. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auclair, D. Measurement errors in forest biomass estimation. In Estimating Tree Biomass Regressions and Their Error, Proceedings of the Workshop on Tree Biomass Regression Functions and Their Contribution to the Error of Forest Inventory Estimates, Syracuse, NY, USA, 26–30 May 1986; USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station: Syracuse, NY, USA, 1987; pp. 133–138. [Google Scholar]

- Eberhardt, D.; Green, E.J. Diameter prediction for correcting continuous forest inventory data. North. J. Appl. For. 1991, 8, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Božić, M.; Đureta, F.; Goršić, E.; Vedriš, M. Utjecaj mjeritelja te pogrešaka pri izmjeri na izmjereni promjer stabla. Šum. List 2020, 144, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deusen, P.C.; Dell, T.R.; Thomas, C.E. Volume growth estimation from permanent horizontal points. For. Sci. 1986, 32, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, C.T.; Bechtold, W.A. Techniques and computations for mapping plot clusters that straddle stand boundaries. For. Sci. Monogr. 1995, 31, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlard, P.G. Myth and reality in growth estimation. In Growth and Yield Estimation from Successive Forest Inventories; Forskningscentret for Skov og Landskab: Lyngby, Denmark, 1993; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Černý, M.; Apltauer, J.; Cienciala, E. Přesnost měření nadzemní biomasy stojících buků technologickou sestavou Field-Map (Accuracy of Shoot Biomass Measurement of Standing Beech Trees with Field-Map Technology). Zprávy Lesn. Výzkumu 2006, 51, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, A.; Gschwantner, T.; Gabler, K.; Schadauer, K. Analysis of Tree Measurement Errors in the Austrian National Forest Inventory. Austrian J. For. Sci. 2012, 129, 153–181. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, J.C. Maintaining a permanent plot data base for growth and yield research: Solutions to some recurring problems. In Growth and Yield Estimation from Successive Inventories; Vanclay, J.K., Skovsgaard, J.D., Gertner, G.Z., Eds.; Forskningscentret for Skov og Landskab: Lyngby, Denmark, 1993; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Coops, N.C.; Tompalski, P.; Goodbody, T.R.H.; Achim, A.; Mulverhill, C. Framework for Near Real-Time Forest Inventory Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Forestry 2023, 96, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhl, M. Inventory concept NFI2. In Swiss National Forest Inventory: Methods and Models of the Second Assessment; Brassel, P., Lischke, H., Eds.; Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL: Birmensdorf, Switzerland, 2001; pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

| Tree Species | Number |

|---|---|

| Abies alba | 10/481 |

| Fagus sylvatica | 4/426 |

| Picea abies | 1/66 |

| Acer pseudoplatanus | 3/46 |

| Corylus avellana | 1/1 |

| Ulmus glabra | 1/3 |

| Tilia platyphyllos | 8/48 |

| Total | 28/1090 |

| Plot ID | COR-OR N1/ha | COR-OR G1/ha | COR-OR V1/ha | COR-OR N2/ha | COR-OR G2/ha | COR-OR V2/ha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 10.88 | 0.32 | 6.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.55 |

| 14 | 0.00 | 1.94 | 31.16 | 0.00 | 0.79 | 3.97 |

| 15 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.96 | 2.30 | 34.68 |

| 19 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 7.96 | 2.37 | 62.88 |

| 31 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −3.63 | −55.28 |

| 48 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 129.92 | 2.19 | 7.24 |

| 52 | 10.88 | 0.62 | 7.36 | −10.88 | −1.09 | −9.25 |

| Tree Species | Model | y Intercept | Slope | R2 | Model p | RM ANOVA | Dunnett’s p * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F (d.f.) | p | |||||||

| Silver fir | OR | 0.2344 | 0.0032 | 0.024 | <0.001 | 12.11 (2, 940) | <0.001 | |

| COR | 0.2115 | 0.0037 | 0.092 | <0.001 | <0.001 | --- | ||

| OR-ERR | 0.2103 | 0.0038 | 0.093 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Common beech | OR | 0.1357 | 0.0030 | 0.053 | <0.001 | 108.58 (2, 842) | <0.001 | |

| COR | 0.1155 | 0.0035 | 0.140 | <0.001 | <0.001 | --- | ||

| OR-ERR | 0.1166 | 0.0035 | 0.137 | <0.001 | 0.816 | |||

| Silver Fir | Common Beech | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stand | COR vs. OR | OR-ERR vs. OR | OR-ERR vs. COR | COR vs. OR | OR-ERR vs. OR | OR-ERR vs. COR |

| 1 (12a) | −2.08% | −1.83% | 0.26% | −2.54% | −2.42% | 0.12% |

| 2 (13a) | −0.63% | −0.25% | 0.38% | −2.04% | −1.95% | 0.09% |

| 3 (15a) | 0.51% | 0.98% | 0.47% | −1.87% | −1.79% | 0.08% |

| 4 | −0.74% | −0.37% | 0.37% | −2.02% | −1.93% | 0.09% |

| 5 | −1.60% | −1.31% | 0.30% | −3.06% | −2.91% | 0.15% |

| Mean | −0.91% | −0.55% | 0.36% | −2.31% | −2.20% | 0.11% |

| SD | 1.00% | 1.08% | 0.08% | 0.49% | 0.46% | 0.03% |

| Min | −2.08% | −1.83% | 0.26% | −3.06% | −2.91% | 0.08% |

| Max | 0.51% | 0.98% | 0.47% | −1.87% | −1.79% | 0.15% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Božić, M.; Goršić, E.; Đureta, F.; Bazijanec, I.; Vedriš, M. Measurement Errors from Successive Inventories on Concentric Circular Field Plots and Their Impact on Volume and Volume Increment in Uneven-Aged Silver Fir Stands. Forests 2025, 16, 1810. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121810

Božić M, Goršić E, Đureta F, Bazijanec I, Vedriš M. Measurement Errors from Successive Inventories on Concentric Circular Field Plots and Their Impact on Volume and Volume Increment in Uneven-Aged Silver Fir Stands. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1810. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121810

Chicago/Turabian StyleBožić, Mario, Ernest Goršić, Filip Đureta, Ivan Bazijanec, and Mislav Vedriš. 2025. "Measurement Errors from Successive Inventories on Concentric Circular Field Plots and Their Impact on Volume and Volume Increment in Uneven-Aged Silver Fir Stands" Forests 16, no. 12: 1810. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121810

APA StyleBožić, M., Goršić, E., Đureta, F., Bazijanec, I., & Vedriš, M. (2025). Measurement Errors from Successive Inventories on Concentric Circular Field Plots and Their Impact on Volume and Volume Increment in Uneven-Aged Silver Fir Stands. Forests, 16(12), 1810. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121810