Insights into Forest Composition Effects on Wildland–Urban Interface Wildfire Suppression Expenditures in British Columbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data and Materials

2.1. Study Area

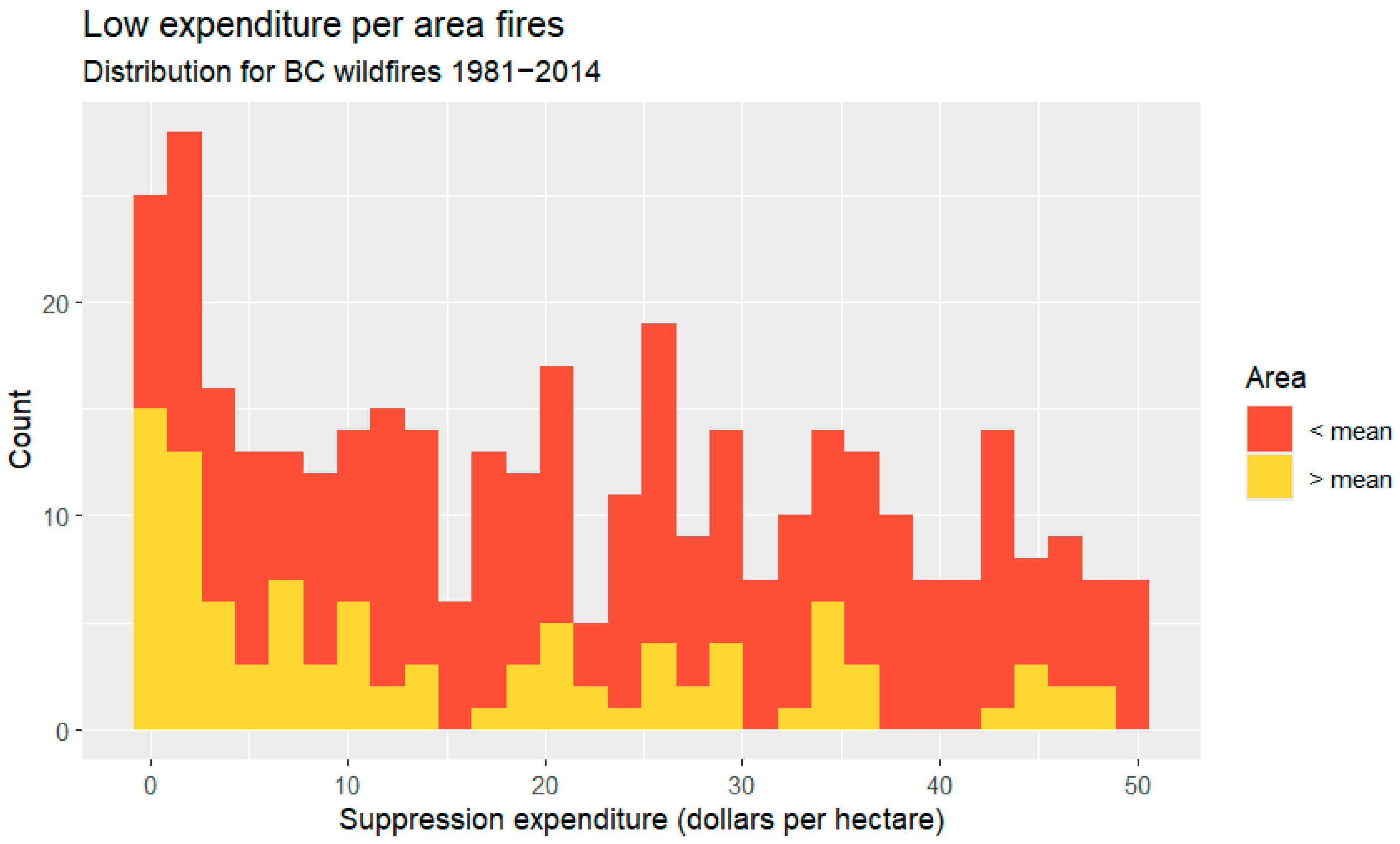

2.2. Fire Suppression Expenditures

2.3. Variable Selection and Data Compilation

3. Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Treatment Effects

5.2. Data Limitations

5.3. Causal Forest Approach

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Appendix A

References

- Collins, L.; Morrison, K.; Buonanduci, M.S.; Guindon, L.; Harvey, B.J.; Parisien, M.A.; Taylor, S.; Whitman, E. Extremely large fires shape fire severity patterns across the diverse forests of British Columbia, Canada. Ecosphere 2025, 16, e70364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisien, M.A.; Barber, Q.E.; Bourbonnais, M.L.; Daniels, L.D.; Flannigan, M.D.; Gray, R.W.; Whitman, E. Abrupt, climate-induced increase in wildfires in British Columbia since the mid-2000s. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, P.; Barber, Q.E.; Taylor, S.W.; Whitman, E.; Castellanos Acuna, D.; Boulanger, Y.; Parisien, M.A. Drivers and impacts of the record-breaking 2023 wildfire season in Canada. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenberg, G. Wildfire Management in the United States: The Evolution of a Policy Failure. Rev. Policy Res. 2004, 21, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, X.J.; Rogers, B.M.; Veraverbeke, S.; Johnstone, J.F.; Baltzer, J.L.; Barrett, K.; Mack, M.C. Fuel availability not fire weather controls boreal wildfire severity and carbon emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 2020, 10, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.E.; Smith, D.J. Interannual climate variability drives regional fires in west central British Columbia, Canada. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2017, 122, 1759–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatzoglou, J.T.; Williams, A.P. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11770–11775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchmeier-Young, M.C.; Malinina, E.; Barber, Q.E.; Garcia Perdomo, K.; Curasi, S.R.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, X. Human driven climate change increased the likelihood of the 2023 record area burned in Canada. Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halofsky, J.E.; Peterson, D.L.; Harvey, B.J. Changing wildfire, changing forests: The effects of climate change on fire regimes and vegetation in the Pacific Northwest, USA. Fire Ecol. 2020, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senande-Rivera, M.; Insua-Costa, D.; Miguez-Macho, G. Spatial and temporal expansion of global wildland fire activity in response to climate change. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. The Effect of Climate Change on Forest Fire Danger and Severity in the Canadian Boreal Forests for the Period 1976–2100. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD039118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, R.; Sun, L.; Taylor, S.W. Modeling Individual Extended Attack Wildfire Suppression Expenditures in British Columbia. For. Sci. 2022, 68, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.M.; Rashford, B.S.; McLeod, D.M.; Lieske, S.N.; Coupal, R.H.; Albeke, S.E. The Impact of Residential Development Pattern on Wildland Fire Suppression Expenditures. Land Econ. 2016, 92, 656–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, R.A.; Kim, Y.S.; Waltz, A.E.; Crouse, J.E. Changes in potential wildland fire suppression costs due to restoration treatments in Northern Arizona Ponderosa pine forests. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 87, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gude, P.H.; Jones, K.; Rasker, R.; Greenwood, M.C. Evidence for the effect of homes on wildfire suppression costs. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2013, 22, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, S.L.; Moghaddas, J.J.; Edminster, C.; Fiedler, C.E.; Haase, S.; Harrington, M.; Youngblood, A. Fire treatment effects on vegetation structure, fuels, and potential fire severity in western U.S. forests. Ecol. Appl. 2009, 19, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T.M.; Vaillant, N.M.; Haas, J.R.; Gebert, K.M.; Stockmann, K.D. Quantifying the Potential Impacts of Fuel Treatments on Wildfire Suppression Costs. J. For. 2013, 111, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, S.J.; Povak, N.A.; Kennedy, M.C.; Peterson, D.W. Fuel treatment effectiveness in the context of landform, vegetation. Ecol. Appl. 2020, 30, e02104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, E.G.; Knapp, E.E.; Brooks, W.R.; Drury, S.R.; Ritchie, M.W. Forest thinning and prescribed burning treatments reduce wildfire severity and buffer the impacts of severe fire weather. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, X.; Tian, X.; Wang, X. The role of fuel treatments in mitigating wildfire risk. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 242, 104957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattioli, W.; Ferrara, C.; Lombardo, E.; Barbati, A.; Salvati, L.; Tomao, A. Estimating Wildfire Suppression Costs: A Systematic Review. Int. For. Rev. 2022, 24, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebert, K.M.; Calkin, D.E.; Yoder, J. Estimating Suppression Expenditures for Individual Large Wildland Fires. West. J. Appl. For. 2007, 22, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, S.G. Forest type and wildfire in the Alberta boreal mixedwood: What do fires burn? Ecol. Appl. 2001, 11, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestry Canada Fire Danger Group. Development and Structure of the Canadian Forest Fire Behavior Prediction System. 1992. For. Can., Ottawa, Ont. Inf. Rep. ST-X-3. 63p. Available online: https://ostrnrcan-dostrncan.canada.ca/handle/1845/235421 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Van Wagner, C.E. Seasonal Variation in Moisture Content of Eastern Canadian Tree Foliage and Possible Effect on Crown Fires. 1967. Can.Dep. For. Rural Develop., For. Branch, Ottawa, ON. Dep. Publ. 1204 22p. Available online: https://ostrnrcan-dostrncan.canada.ca/handle/1845/223785 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Alexander, M.E. Surface fire spread potential in trembling aspen during summer in the Boreal Forest Region of Canada. For. Chron. 2010, 86, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintilio, D.; Alexander, M.E.; Ponto, R.L. Spring Fires in a Semimature Trembling Aspen Stand in Central Alberta. 1991. For. Can., North. For. Cent., Edmonton, AB. Inf. Rep. NOR-X-323. 30p. Available online: https://ostrnrcan-dostrncan.canada.ca/handle/1845/233924 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Peter, B.; Milovanovic, M.; Cataldo, N.; Scott, M. On-reserve forest fuel management under the Federal Mountain Pine Beetle Program and Mountain Pine Beetle Initiative. For. Chron. 2016, 92, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davis, J.M.; Heller, S.B. Using causal forests to predict treatment heterogeneity: An application to summer jobs. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athey, S.; Wager, S. Estimating Treatment Effects with Causal Forests: An Application. 2019. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1902.07409.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Jain, P.; Coogan, S.C.; Subramanian, S.G.; Crowley, M.; Taylor, S.; Flannigan, M.D. A review of machine learning applications in wildfire science and management. Environ. Rev. 2020, 28, 478–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.S.; Wichmann, B. Machine learning estimates on the impacts of detection times on wildfire suppression costs. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0313200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawadekar, N.; Kezios, K.; Odden, M.C.; Stingone, J.A.; Calonico, S.; Rudolph, K.; Zeki Al Hazzouri, A. practical guide to honest causal forests for identifying heterogeneous treatment effects. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2023, 192, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehill, P. How do applied researchers use the Causal Forest? A methodological review. Int. Stat. Rev. 2025, 202593, 288–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streyczek, J. The Economist’s Guide to Causal Forests. University of Boconi, Milan, 2022. Available online: https://julianstreyczek.github.io/assets/pdf/causalforests.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Rana, P.; Miller, D.C. Machine learning to analyze the social-ecological impacts of natural resource policy: Insights from community forest management in the Indian Himalaya. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 024008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wager, S.; Athey, S. Estimation and Inference of Heterogeneous Treatment Effects using Random Forests. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2018, 113, 1228–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athey, S.; Tibshirani, J.; Wager, S. Generalized Random Forests. Ann. Stat. 2018, 47, 1148–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilani, H.R.; Innes, J.L. The state of British Columbia’s forests: A global comparison. Forests 2020, 11, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Reporting BC. Trends in B.C.’s Population Size & Distribution 2018. Available online: https://www.env.gov.bc.ca/soe/indicators/sustainability/bc-population.html (accessed on 26 February 2024).

- Tymstra, C.; Stocks, B.J.; Cai, X.; Flannigan, M.D. Wildfire management in Canada: Review, challenges and opportunities. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 5, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B.C. Wildfire Service. Wildfire Service. Government of British Columbia. 2024. Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/safety/wildfire-status (accessed on 27 February 2024).

- B.C. Ministry of Finance. 2023. Budget and Fiscal Plan 2023/24–2025/26. Available online: https://ouvert.canada.ca/data/dataset/10406465-e4d6-48f5-a721-6eb2d7860d2d (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Reimer, J.; Thompson, D.K.; Povak, N. Measuring Initial Attack Suppression Effectiveness through Burn Probability. Fire 2019, 2, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Consumer Price Index, Annual Average, Not Seasonally Adjusted. 2025. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1810000501 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- B.C. Wildfire Service. BC Wildfire Wildland Urban Interface Risk Class Data Catalogue. 2019. Available online: https://catalogue.data.gov.bc.ca/dataset/bc-wildfire-wildland-urban-interface-risk-class (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Xi, D.D.; Dean, C.B.; Taylor, S.W. Modeling the duration and size of extended attack wildfires as dependent outcomes. Environmetrics 2020, 31, e2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wagner, C.E. Structure of the Canadian Forest Fire Weather Index; Forestry Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1974; Available online: https://ostrnrcan-dostrncan.canada.ca/handle/1845/228434 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Natural Resources Canada. Canadian Digital Elevation Model. 2013. Available online: https://open.canada.ca/data/en/dataset/7f245e4d-76c2-4caa-951a-45d1d2051333 (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Beaudoin, A.; Bernier, P.Y.; Guindon, L.; Villemaire, P.; Guo, X.J.; Stinson, G.; Hall, R.J. Mapping attributes of Canada’s forests at moderate resolution through kNN and MODIS imagery. Can. J. For. Res. 2014, 44, 521–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Census of Population, Population and Dwelling Counts, for Canada and Designated Places, 2011 and 2006 Censuses. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/Table-Tableau.cfm?LANG=Eng&T=1301&SR=1251&S=9&O=A&R (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Statistics Canada. Census of Population, Population and Dwelling Counts, for Population Centres, 2011 and 2006 Censuses. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/Table-Tableau.cfm?LANG=Eng&T=801&S=51&O=A (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Hirano, K.; Imbens, G.W. The Propensity Score with Continuous Treatments. In Applied Bayesian Modeling and Causal Inference from Incomplete-Data Perspectives; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Mealli, F.; Kioumourtzoglou, M.A.; Dominici, F.; Braun, D. Matching on generalized propensity scores with continuous exposures. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2024, 119, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenova, V.; Chernozhukov, V. Debiased machine learning of conditional average treatment effects and other causal functions. Econom. J. 2021, 24, 264–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hély, C.; Bergeron, Y.; Flannigan, M. Effects of stand composition on fire hazard in mixed-wood Canadian boreal forest. J. Veg. Sci. 2000, 11, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, M.S.; Thompson, M.P.; Calkin, D.E. Examining heterogeneity and wildfire management expenditures using spatially and temporally descriptive data. J. For. Econ. 2016, 22, 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Calkin, D.E.; Gebert, K.M.; Venn, T.J.; Silverstein, R.P. Factors influencing large wildland fire suppression expenditures. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2008, 17, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hand, M.S.; Gebert, K.M.; Liang, J.; Calkin, D.E.; Thompson, M.P.; Zhou, M. Economics of Wildfire Management: The Development and Application of Suppression Expenditure Models; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Wildfire Coordinating Group. Wildland Fire Decision Support Tools: A Guide for Agency Administrators; National Interagency Fire Center: Boise, ID, USA, 2023.

- Looney, C.E.; Brodie, E.G.; Fettig, C.J.; Ritchie, M.W.; Knapp, E.E. Ecological forestry treatments affect fine-scale attributes within large experimental units to influence tree growth, vigor, and mortality in ponderosa pine/white fir forests in California, US. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 561, 121814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, E.K.; Peterson, D.W. Seeding and fertilization effects on plant cover and community recovery following wildfire in the Eastern Cascade Mountains, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyden, S.; Binkley, D.; Senock, R. Seeing the forest for the heterogeneous trees: Stand-scale resource distributions create differences in tree growth. Ecology 2012, 93, 1202–1212. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, K.A.; Bayne, E. Breeding Bird Communities in Boreal Forest of Western Canada: Consequences of “Unmixing” the Mixedwoods. Condor 2000, 102, 759–769. [Google Scholar]

- Rozario, K.; Oh, R.R.; Marselle, M.; Schröger, E.; Gillerot, L.; Ponette, Q.; Bonn, A. The more the merrier? Perceived forest biodiversity promotes short-term mental health and well-being—A multicentre study. People Nat. 2023, 6, 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Decile | Expenditure | Expenditure Per Hectare |

|---|---|---|

| min | 7 | 0 |

| 10 | 1965 | 106 |

| 20 | 6259 | 319 |

| 30 | 15,159 | 685 |

| 40 | 29,403 | 1228 |

| 50 | 50,204 | 2092 |

| 60 | 80,424 | 3334 |

| 70 | 122,448 | 5256 |

| 80 | 217,098 | 8231 |

| 90 | 493,243 | 14,276 |

| max | 25,193,978 | 224,529 |

| Variable | Variable Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Fire Characteristics | ||

| ln (Fire size) | Natural log of final fire size in hectares | BC Wildfire Service |

| ln (Fire perimeter) | Natural log of final fire perimeter in kilometers. | BC Wildfire Service |

| Duration of fire | The duration from ignition to control | BC Wildfire Service |

| Julian day of the year | Julian day of fire ignition | BC Wildfire Service |

| Fire year | Year of fire | BC Wildfire Service |

| Cause of fire | Dummy variables for human caused and lightning caused fires | BC Wildfire Service |

| Fire Environment | ||

| ln (DSR)—Daily severity rating | An index of fire danger based on wind speed and fuel moisture | NRCan |

| ln (Slope) | Natural log of the percentage slope of the area | NRCan |

| In (Elevation) | Natural log of the elevation of the fire ignition point in meters | NRCan |

| Aspect | The sin and cosine of the aspect at the fire ignition point in radians | NRCan |

| ln (Topographic roughness) | An index of topographical roughness Index (TRI) | NRCan |

| Fuel type | Dummy variables or Forested Area and Grassland | NFI |

| Percent coniferous | The percent of trees that are coniferous near the ignition point. | NFI |

| Eco-province dummy variables | 10 dummy variables for the eco-provincial regions of BC | NRCan |

| Values at Risk | ||

| ln (Population within 30 km) | Population of within 30 km of fire | Stats Canada |

| ln (Distance WUI density 3+) | Distance to the nearest level three or higher density WUI | BC Wildfire Service |

| Land tenure dummies | Dummy variables for private land, crownland, parks, and other land. | BC Wildfire Service |

| Fire Response | ||

| ln (Detection time delay) | Natural log of hours between fire ignition and discovery | BC Wildfire Service |

| ln (Discovery size) | Natural log of final fire size when discovered | BC Wildfire Service |

| ln (Fire load anomaly) | Difference between the number of fires burning and the average amount. | BC Wildfire Service |

| MacMillan et al. [12] (n = 5459) | Causal Forest | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4–40 ha (n = 2997) | 40–200 ha (n = 810) | >200 ha (n = 417) | All Fires (n = 4224) | |||||||

| Percent conifer | 0.0020 | *** | 0.0031 | *** | 0.0065 | *** | 0.0050 | ** | 0.0037 | *** |

| (0.0005) | (0.0007) | (0.0014) | (0.0018) | (0.0006) | ||||||

| 4–40 ha | 40–200 ha | >200 ha | All Fires | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grouping by CATE Estimate | 0.0030 | *** | 0.0064 | *** | 0.0042 | ** | 0.0037 | *** |

| (0.0007) | (0.0014) | (0.0017) | (0.0006) | |||||

| Mean forest prediction | 0.9226 | *** | 0.9946 | *** | 1.0338 | ** | 0.9063 | *** |

| (0.2551) | (0.2117) | (0.3832) | (0.1651) | |||||

| Differential forest prediction | 1.5247 | *** | 1.2585 | * | −0.9101 | 1.8208 | *** | |

| (0.3862) | (0.7467) | (1.4997) | (0.3597) |

| 4–40 ha (n = 2997) | 40–200 ha (n = 810) | >200 ha (n = 417) | All Fires (n = 4224) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln(DSR) | 0.0025 | ** | −0.0020 | 0.0019 | * | |||

| (0.0009) | (0.0031) | (0.0008) | ||||||

| ln (Topographic roughness) | −0.0006 | 0.0003 | ||||||

| (0.0005) | (0.0004) | |||||||

| ln (Distance WUI density 3+) | −0.0007 | 0.0017 | 0.0001 | |||||

| (0.0005) | (0.0011) | (0.0005) | ||||||

| ln (Deviation count) | −0.0003 | −0.0011 | ||||||

| (0.0005) | (0.0016) | |||||||

| Private land | 0.0053 | ** | 0.0056 | *** | ||||

| (0.0016) | (0.0014) | |||||||

| ln (Detection time delay) | 0.0088 | ** | ||||||

| (0.0033) | ||||||||

| Julian day of the year | −0.0001 | * | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | * | |||

| (0.0000) | (0.0001) | (0.0000) | ||||||

| In (Slope) | 0.0000 | |||||||

| (0.0008) | ||||||||

| Duration | −0.0004 | |||||||

| (0.0002) | ||||||||

| ln (Discovery size) | 0.0014 | |||||||

| (0.0010) | ||||||||

| ln (Fire perimeter) | −0.0013 | |||||||

| (0.0019) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of Natural Resources (His Majesty). Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, L.; Chan, R.; Endo, K.; Taylor, S.W. Insights into Forest Composition Effects on Wildland–Urban Interface Wildfire Suppression Expenditures in British Columbia. Forests 2025, 16, 1626. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111626

Sun L, Chan R, Endo K, Taylor SW. Insights into Forest Composition Effects on Wildland–Urban Interface Wildfire Suppression Expenditures in British Columbia. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1626. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111626

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Lili, Rico Chan, Kota Endo, and Stephen W. Taylor. 2025. "Insights into Forest Composition Effects on Wildland–Urban Interface Wildfire Suppression Expenditures in British Columbia" Forests 16, no. 11: 1626. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111626

APA StyleSun, L., Chan, R., Endo, K., & Taylor, S. W. (2025). Insights into Forest Composition Effects on Wildland–Urban Interface Wildfire Suppression Expenditures in British Columbia. Forests, 16(11), 1626. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111626