Abstract

This paper focuses on analysing the structural performance of fast-grown hardwood versus softwood glued laminated timber (GLT or glulam) beams with the aim to evaluate the potential structural use of the two main species planted in the country. In Uruguay, the first forest plantations date from the 1990s and are comprised mainly of Eucalyptus ssp. and Pinus spp. No one species were planted for a specific industrial purpose. However, while eucalyptus was primarily destined for the pulp industry, pine, which is now reaching its forest rotation, had no specific industrial destination. Timber construction worldwide is mainly focused on softwood species with medium and long forest rotation. The objective of the present work is, therefore, to analyse and compare the potential of eucalyptus (Eucalyptus grandis) and loblolly/slash pine (Pinus elliottii/taeda) to produce glulam beams for structural purposes. Experimental tests were made on sawn timber and GLT beams manufactured under laboratory conditions for both species. The relationship between the physical and mechanical properties of sawn timber showed that, for similar characteristic values of density (365 kg/m3 for pine and 385 kg/m3 for eucalyptus), and similar years of forest rotation (20–25 years for pine and around 20 years for eucalyptus) and growth rates, the structural yield of eucalyptus was higher compared to that of pine. The superior values of modulus of elasticity found in the hardwood species explained this result. Since there is no strength classes system for South American wood species, the European system was the basis for estimating and assigning theoretical strength classes from the visual grades of Uruguayan timbers. For sawn timber, a C14 strength class for pine and C20 for eucalyptus were assigned. Results showed that pine GLT could be assigned to a strength class GL20h, and eucalyptus glulam to GL24h and GL28h, demonstrating the potential of both species for producing glulam beams. Even though eucalyptus showed a better yield than pine, the technological process of manufacturing eucalyptus glulam was more challenging in terms of drying time and gluing than in the case of pine, which derivates in higher economic costs.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is facing growing pressure to implement sustainable practices to mitigate the effects of climate change. One area of particular interest is the utilization of wood for structural purposes, which represents a relevant ratio of wood volume per square meter of building compared with other wood products used in construction. Ratios varying between 0.1 and 0.2 m3/m2 were reported by Hurtado et al. [1] for single-family houses and long-span timber structures in Chile, while the ratios between 0.3 and 0.4 m3/m2 were found by Basterra et al. [2] in mid-rise timber buildings (≥4 floors) in Southwestern Europe.

Wood is a renewable material that can significantly reduce carbon emissions compared to traditional construction materials, such as steel or concrete, and can store carbon during its service life. Therefore, timber buildings can be considered carbon sinks [3]. Nowadays, just about 7% of the sawn wood production in EU-27 (109 MMm3) is destined to engineered wood products (EWPs) for structural purposes [4,5]. However, sawn wood production is expected to increase at an annual rate of 1.8% by 2030 [6]. Around 50% of the production are EWPs made from softwood species to substitute steel (40%), concrete (40%), and masonry and other materials (20%) in construction [6].

Fast-growing species have become an alternative available timber for European industry in recent decades, including hardwood [7,8]. The rising demand for softwood for industrial applications, and the increasing quantity of hardwood in forests [9,10] offer an opportunity for the wood industry to develop new hardwood products and markets, particularly in the construction sector. However, even in European countries, where significant volumes of hardwood are produced, just about 5% to 16% are produced for sawn timber [10]. In Canada, the harvest volumes in 2020 indicated a surplus of hardwood resources and the need for an increase in its utilization, particularly for EWPs, such as glued laminated timber (GLT) and cross-laminated timber (CLT) [11]. A similar situation is facing Australia, where Tasmania accounts for approximately 35% of the national hardwood available. Eucalyptus nitens is the main hardwood species, and the large supply has raised a lot of interest in utilizing this raw material to produce wood products for the building industry [12].

Hardwood species typically show superior strength and stiffness compared to softwood. However, there are inherent challenges associated with their use for manufacturing EWPs, such as bonding or drying, which may have an impact on their economic viability [13,14].

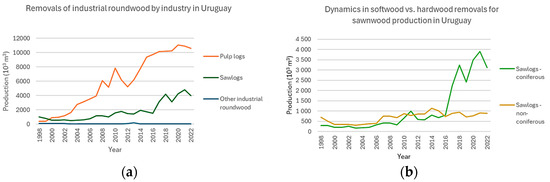

During the 1990s, the forestry sector in Uruguay experienced a period of substantial growth, with the area of planted forests reaching 1.3 million hectares in 2021 [15]. Eucalyptus spp. represents 71% of the planted area, 42% is accounted for by eucalyptus grandis or rose gum (Eucalyptus grandis) and Sydney blue glum (Eucalyptus saligna), while 17% is attributed to Southern blue gum (Eucalyptus globulus). Pinus spp. constitutes 18% of the planted area, mainly Loblolly and Slash pine (Pinus taeda and Pinus elliottii), usually commercialised together. Most of the removals are destined for pulp production, followed by the sawn wood industry (Figure 1a), which has seen a notable increase since 2016, mainly from coniferous, also named softwood species (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Dynamics in wood production in Uruguay: (a) industrial roundwood removals by industry; (b) removals of sawlogs for the sawmill industry: softwood vs. hardwood (developed from FAOSTAT database, 2023).

To boost the use of planted wood species for structural applications in 2018, a set of Uruguayan standards for visual strength grading of sawn wood for pine [16] and eucalyptus [17] was developed. The standards were the result of several research works [18,19]. In 2023, the first plant devoted to producing structural glued laminated timber (glulam or GLT) and cross-laminated timber (CLT) made of pine was established in the country and the first buildings are being constructed (Figure 2a). Furthermore, eucalyptus has shown potential for glulam production [20,21].

Figure 2.

(a) GLT and CLT made of pine timber in the Garzón School (Source: Arboreal); (b) Up to 26 m span of Eucalyptus grandis glulam beams at the MACA Museum (Source: Oak Ingeniería).

The structural aptitude and aesthetic possibilities of Eucalyptus grandis called the attention of Uruguayan architects and engineers. This species was used for the design and construction of the iconic Museum of Contemporary Art Atchugarry (MACA) located in Maldonado, as shown in Figure 2b [22]. It is the only building constructed with structural eucalyptus GLT in the country and is considered as a flagship to demonstrate the opportunities of this hardwood species. The GLT beams and columns were manufactured outside the country from national raw material.

In line with this forthcoming availability of structural timber and other locally produced EWPs, such as plywood, the National government is now promoting timber for structural applications through several initiatives, the most recent proposal being the roadmap for the promotion of social housing in wood in Uruguay [23]. These guidelines promote both single-family housing and mid-rise residential buildings. The first experiences have shown a favourable reception by the users [24]. The growing concern for the environment and the multiple benefits of using mass timber are leading to position structural timber as a building material. Before attaining that scenario and to develop a viable forest–timber–construction industrial chain, several drawbacks must be analysed [25,26,27]. One drawback is related to the yield of the softwood and hardwood lumber for EWPs, in particular for GLT production, which is one of the partial objectives of this work.

Fast-growing plantations have been introduced in several countries to meet the increased demand for timber. This trend includes the short forest rotation of hardwood (lower than 30 years) to improve the profitability of the industry. The recent use of species such as Liriodendrum tulipifera in Japan [28], Eucalyptus grandis in Turkey [29], or Tectona grandis in Costa Rica [30] are some examples.

In Uruguay, with average growth rates of 19 to 24 m3 ha−1 y−1, trees grow so fast and attain commercial size for lumber, which is commonly harvested at the age of 20 to 25 years for Pinus elliottii and P. taeda (pine), and between 16 and 20 years for Eucalyptus grandis (eucalyptus) [31,32,33]. As a result of the cutting cycles, it was found that the wood, mostly from pine, showed high percentages of juvenile wood being different from that of pine harvested from older, slow-growing natural stands [34]. The end-product concern with juvenile wood is that its physical and mechanical properties are inferior to those of mature wood. Depending on the manufacturing process, i.e., length of boards, removal of certain defects, etc., part of this resource could be recovered and used as raw material for GLT production. Therefore, the yield of the lumber from the most common species used for GLT must be addressed.

The objective of this study is to analyse and compare the potential of fast-grown softwood and hardwood species (Pinus elliottii/taeda and Eucalyptus grandis) to produce glulam beams for structural purposes. The performance of pine and eucalyptus timbers from Uruguay to produce glulam was investigated from the raw material to their end-use in the form of beams.

2. Materials and Methods

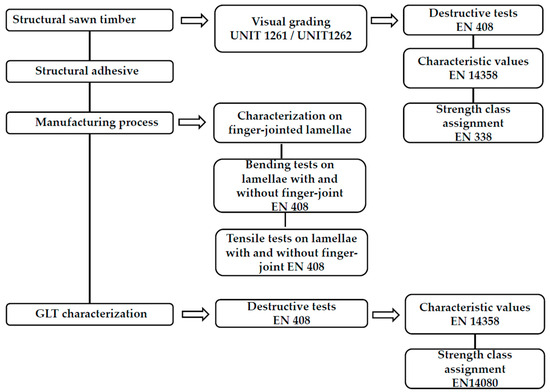

For a better understanding of the work a flow chart is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flow chart for this study.

2.1. Structural Sawn Timber

A total of four samples, two per species, of kiln dried sawn timber of pine and eucalyptus with dimensions of 50 × 145 × 3000 mm3 for pine and 36 × 90 × 2400 mm3 for eucalyptus were selected as representative of the current commercialised sizes. All samples were visually strength graded. Table 1 shows the quality criteria for the visual grades, EC1 for pine and EF1 for eucalyptus, provided by the Uruguayan standards UNIT 1261 [16] and UNIT 1262 [17]. Table 1 also includes the characteristic values of bending strength (fm,k), modulus of elasticity (E0,m), and density (ρk) established in the UNIT standards for the visual grades of both species. These values have been determined based on technical reports [17,34].

Table 1.

Quality criteria and characteristic values for assessment of visual grade of pine and eucalyptus (UNIT 1261 and UNIT 1262).

Note that comparison of the mean and characteristic density values of Uruguayan eucalyptus show lower values than those reported in EN 338 [35]. Most temperate hardwood species are graded as strength classes D, e.g., Southern blue glum from Spain (D40), beech from France, Belgium, and Germany (D40 and D35), or sweet chestnut from Spain (D27 and D24) [36]. However, there is a background in the EN 1912 [36] of hardwood graded as strength classes C due to the density values being lower than that of the most temperate hardwood. Table 2 shows examples of European hardwood graded as strength classes C.

Table 2.

European hardwood species graded as strength classes C, developed from [35,36].

2.2. Lamellas and Finger-Joint Testing

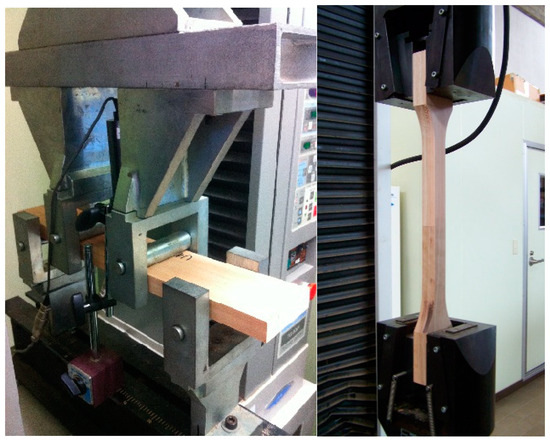

The structural behaviour of the lamellae comprising the GLT beams was evaluated by bending and tensile tests on specimens with and without finger-joints. A polyurethane-reactive adhesive (PUR) known as LOCTITE® PURBOND HB S 309 (Henkel, Düsseldorf, Germany) for gluing the finger joints, was used. Forty specimens of each species, with a cross-section of 24 × 73 mm2 and 432 mm long, were tested in bending according to EN 408 [37]. In addition, 31 specimens of eucalyptus with and without finger-joints under tensile tests were evaluated. Tensile test specimens with a free length of 192 mm between clamps were machined to a cross-section of 17 × 22 mm2 in the central section to avoid wood failure at the clamps. Figure 4 shows the bending and tensile tests on small clear specimens conducted at the Laboratorio Tecnológico del Uruguay (LATU). The failure load was recorded, and the bending (fm,l,k and fm,j,k without and with finger-joint, respectively) and tensile (ft,0,l,k and ft,0,j,k without and with finger-joint, respectively) strength were computed according to the equations given by EN 408 [37].

Figure 4.

Bending (left) and tensile (right) tests on small clear-wood specimens at LATU.

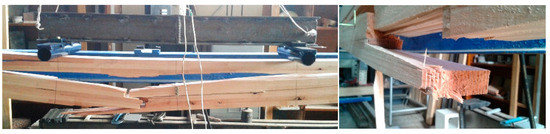

2.3. Glulam

Pine and eucalyptus sawn timber visually graded as EC1 and EF1, respectively, were selected for glulam production. The minimum length of the blocks considered for lamella manufacturing was 400 mm. The finger-joint geometry followed the requirements of EN 14080 [38], with a teeth length of 15 mm and other parameters defined under the specifications set forth by Moya et al. [20].

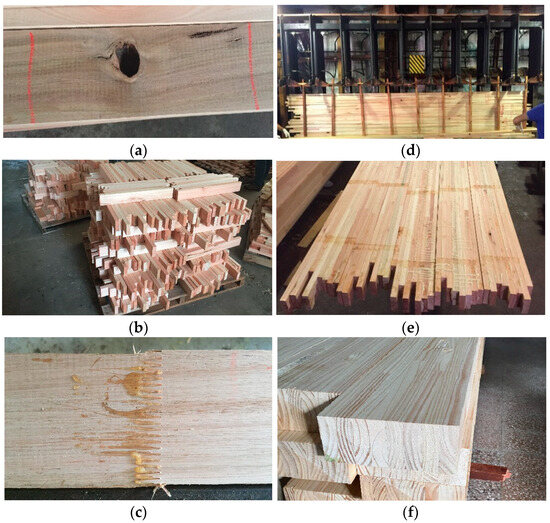

The standard EN 14080 [38] was considered as the basis for glulam manufacturing, though neither of the two species studied in the present work are among those mentioned in that standard. Three groups of testing samples were prepared: 33 GLT pine beams with dimensions of 75 × 195 × 3510 mm3, 33 GLT and 21 GLT eucalyptus beams with dimensions of 75 × 195 × 3510 mm3, and 95 × 240 × 4560 mm3, respectively, were manufactured. The lamellae were glued using the same PUR adhesive as for the finger-joints. The GLT beams were tested in bending according to EN 408 [37] and the characteristic values of bending strength (fm,g,k), modulus of elasticity (E0,mean,g), and density (ρg,k) were determined according to EN 14080 [38] and EN 14358 [39]. The height factor was applied to the individual values of bending strength, and stiffness and density were adjusted to the reference moisture content (MC) of 12%. Figure 5 depicts the manufacturing process of the glulam beams.

Figure 5.

The manufacturing process of glulam: (a) Grading, (b) Blocks, (c) Finger-joint, (d) Pressing, (e) Eucalyptus glulam before planing, (f) Pine glulam after planing.

While the characteristic values obtained from EN 14358 [39] for the sawn timber are adjusted by the sample size according to EN 384 [40], for glulam no sample size adjustment is required. Accordingly, the characteristic values reported in this study are directly derived from EN 14358 [39].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sawn Timber

In the absence of a system of strength classes for Uruguayan or South American wood species, and because they are not yet included in the European standard EN 1912 [36], an estimation of the assignment of European strength classes from the UNIT visual grades was made. EN 1912 assigns the strength classes defined in EN 338 [35] to the visual grades determined by the visual grading national standards. Intending to evaluate if the relationships between properties of the Uruguayan species were in accordance with those established in the European standard EN 338, the stiffness-to-density (E0,mean/ρk) and strength-to-density (fm,k/ρk) ratios for pine and eucalyptus were determined and compared with those provided by EN 338.

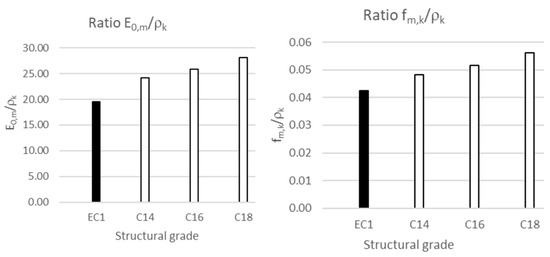

3.1.1. Relations Between Visual Grades and Strength Classes for Pine

Based on the characteristic values of the visual grade EC1, shown in Table 1 (fm,k = 15.5 N/mm2, E0,m = 7139 N/mm2, and ρk = 365 kg/m3), pine could be assigned to the strength class C14 (fm,k = 14 N/mm2; E0,m = 7 kN/mm2; and ρk = 290 kg/m3), with the modulus of elasticity being the governing parameter. It should be noted that those values arise from applying the sample size adjustment factor provided by EN 384 [40].

Values are similar to those given by Rosa et al. (2023) [41], who found that Slash pine cultivated in Brazil exhibits structural capacity from the sixth year onwards. Pine between 6 and 18 years old (E0,m = 7315 N/mm2) could be graded as C14, according to EN 338; between 18 and 24 years old (E0,m = 8259 N/mm2) as C16; and between 24 and 30 years old (E0,m = 9617 N/mm2) as C20.

The stiffness-to-density ratio of the visual grade EC1 (E0,mean/ρk_EC1 = 19.6) was slightly lower than that of the strength class C14 (E0,mean/ρk_C14 = 24.1). This is due to the fact that, for the same stiffness values, Uruguayan pine exhibits a higher density value compared to that of the strength class C14. Similar behaviour was observed for the strength-to-density ratio, which was lower for the visual grade EC1 than for the strength class C14 (fm,k/ρk_EC1 = 0.042 < fm,k/ρk_C14 = 0.048).

Figure 6 shows the ratios for the visual grade EC1 of Uruguayan pine (black colour) compared to those of the strength classes C14, C16, and C18. It can be observed that the closest value to the ratios for the visual grade EC1 are those corresponding to the strength class C14.

Figure 6.

Comparison between E0,mean/ρk and fm,k/ρk ratios of the pine visual grade EC1 with those from European softwood strength classes C14, C16, and C18.

3.1.2. Relations Between Visual Grades and Strength Classes for Eucalyptus

Stiffness-to-density and strength-to-density ratios were analysed for strength classes C and D for softwood and hardwood species, respectively. Stiffness-to-density ratio for the visual grade EF1 (E0,mean/ρk_EF1 = 31.0) was much closer to that of the strength class C24 (E0,mean/ρk_C24 = 31.4) than to D24 (E0,mean/ρk_D24 = 20.6). Similar behaviour was observed in the case of the strength-to-density ratio of the visual grade EF1 (fm,k/ρk_EF1 = 0.055), which was closer to that of the strength class C18 (fm,k/ρk_C18 = 0.056) or C20 (fm,k/ρk_C20 = 0.060) than to D18. The observed ratios for eucalyptus graded as EF1 are consistent with those for Eucalyptus grandis from Argentina (E0,m/ρk = 31.6 and fm,k/ρk = 0.07) [42] and Eucalyptus nitens from Spain (E0,m/ρk = 29.7 and fm,k/ρk = 0.08) [43].

Figure 7 shows the ratios for the visual grade EF1 of Uruguayan eucalyptus (black colour) compared to those of the softwood strength classes C20, C22, and C24 (white colour) and the hardwood strength classes D18 and D20 (grey colour).

Figure 7.

Ratios E0,m/ρk and fm,k/ρk for the visual grade of eucalyptus (EF1) compared with those from softwood (C) and hardwood (D) strength classes.

Therefore, it seems reasonable that Uruguayan eucalyptus graded as EF1 be assigned to a strength class C. This assignation resulted in a strength class C20 (fm,k = 20 N/mm2, E0,m = 9500 N/mm2, and ρk = 330 kg/m3) according to EN 338 [35], when the sample size adjustment provided by EN 384 [40] is applied. This assignation results in properties lower than E. grandis from Argentina graded as class 2 (fm,k = 24 N/mm2; E0,m = 12.500 N/mm2; ρk = 430 kg/m3) [42]. Neglecting the sample size adjustment factor, the strength class assigned would be C24 (fm,k = 24 N/mm2, E0,m = 11,000 N/mm2, and ρk = 350 kg/m3), closer to the values provided by IRAM 9662-2 [42] for the Argentinean eucalyptus, to which no correction factor for sample size was applied.

3.1.3. Machine Grading

The current trend in wood grading is to implement in-line machine grading in the sawmills instead of visual grading. It improves the strength grading yield in both, with a larger percentage of pieces assigned to the highest strength class and a smaller percentage of pieces rejected. A recent study of softwood species [44] quantified the increase in the highest strength classes for in-line machine grading in comparison to the visual grading method. The percentage increase was found to be 49% for maritime pine, 30% for radiata pine, and 36% for Scots pine. Similarly, the percentage of rejection decreased by 10% and 20% for maritime and Scots pine, respectively. Therefore, the assignment to strength classes for Uruguayan pine and eucalyptus could be increased if machine grading is applied. It was already demonstrated in the case of pine, where strength classes up to C30 were obtained from machine grading, and certified by the notified body MPA [45].

3.1.4. Sawn Timber Performance

The first criterion used to evaluate the sawn wood performance is the relationship between the physical and mechanical properties with the forest rotation. The properties for both pine and eucalyptus species were obtained from Table 1 and compared with their forest rotation (between 20 and 25 years for pine and between 16 and 20 for eucalyptus), as mentioned previously in Section 1. For a forest rotation of 20 years in both cases, eucalyptus showed higher yield for the three main properties, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Ratios of physical and mechanical properties and forest rotation (T) for pine and eucalyptus sawn timber (authors source).

The second criterion is the conversion factor from sawlogs to sawn wood, expressed in %. The conversion factor for pine in Uruguay is 45%; i.e., 45% of the sawlog volume is converted into sawn wood; while for eucalyptus it is 40% [46]. The lower conversion factor of hardwood compared to softwood is one of the challenges for producing economically competitive products for the construction sector, followed by technological aspects, such as drying or gluing, for GLT production.

Round wood to lumber conversion factors are affected by many drivers of efficiency, such as log quality and size, both having substantial impacts on conversion efficiency, how roundwood volume is measured, and the efficiency of the sawing process. This explanation could be applicable to the lower conversion ratio of Uruguayan hardwood [47].

The manufacturing of eucalyptus glulam implies a reduction in the thickness of the lamellas, compared with softwood, with the objective of facilitating the drying process and reducing costs. Lamellas of 25 mm thickness were used for the manufacturing of curved glulam beams of eucalyptus grandis in the MACA museum [22]. This is considerably lower than the common thickness of softwood glulam, which typically ranges from 35 to 45 mm. The drying time in 25 mm thickness eucalyptus lamellas increased by a factor of 4.25 with respect to 40 mm thickness lamellas of pine [48]. Furthermore, the thinner lamellas of eucalyptus implied that the number of glue lines increased by 1.6 compared to pine, resulting in a larger amount of adhesive [22]. Cracking or splitting during the drying process, excessive warping, or the presence of brittle heartwood were other difficulties found in the technological processing of eucalyptus grandis [49].

An increase of one-third in the cost of the eucalyptus grandis glulam structure compared to a spruce glulam structure was observed in the MACA museum building [22], while costs up to 3 times higher for hardwood compared to softwood were reported by Schlotzhauer et al. (2019) [50]. This increase in the cost is not yet compensated by the increase in the mechanical properties of hardwood compared to softwood.

3.2. Lamellas

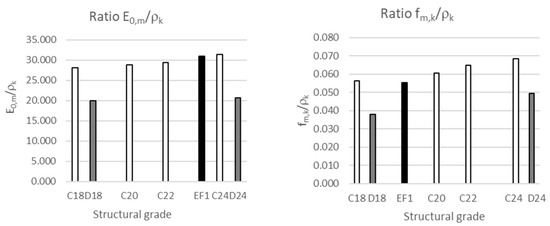

3.2.1. Failure Mode of the Finger Joints

The failure modes of the finger joints according to the three types described by Vega et al. [51] were analysed. Failure mode 1 corresponds to a rupture occurring 100% by wood, failure mode 2 to a partial failure by wood and partially by adhesive, and failure mode 3 to a rupture caused 100% by adhesive.

In the case of pine, mode 1 dominated the type of failure of the whole sample tested in bending (40 specimens), demonstrating the adequate manufacturing process in terms of the selected adhesive and pressing process. Failure modes 2 and 3 were observed in 20% of the specimens of eucalyptus tested in bending, suggesting that the finger-joint manufacturing process (adhesive type, gluing, pressing, etc.) applied to pine did not work for eucalyptus. Similar results were observed in the finger joints of eucalyptus tested in tension, where 35% of the sample failed by failure mode 2 or 3. Figure 8 shows typical failure mode 1 of eucalyptus tested in bending and tension.

Figure 8.

Failure mode in eucalyptus’ finger-joint tested in bending (above) and tension (below).

The challenge of finger joint gluing for structural purposes in Eucalyptus ssp. has been reported by several authors, mainly in specimens obtained from young trees. Percentages between 42% and 68% of failure mode 1, depending on the end-pressure in the finger-joint manufacturing, were reported by Lara-Bocanegra et al. (2017) [52] for Eucalyptus globulus glued with one-component PUR. Percentages of 44% were found by Segundinho et al. (2017) [53] for 6–8-years-old Eucalyptus cloeziana glued with one-component PUR adhesive. The percentage increased to 81% in 11-years-old Eucalyptus grandis glued with a bi-component or castor oil-based polyurethane adhesive according to Oliveira et al. (2024) [54]. Harvesting of young trees and manufacturing the finger joints in wet conditions resulted in a better performance compared with dried wood [55]. There are a few patented methods for processing wet wood of eucalyptus grandis (moisture content higher than 30%) from trees with a forest rotation of 5 to 11 years [49].

3.2.2. Strength

Table 4 shows the mean and characteristic values of strength of lamellas with and without finger joints. Bending strength for pine and both bending and tensile strength for eucalyptus, are shown. For the calculation of the characteristic values of the finger-joint strength, only the specimens with failure mode 1 (failure 100% by wood) were considered.

Table 4.

Bending and tensile strength of lamellas.

As observed in Table 4, the bending strength of eucalyptus was 1.1 times higher than that of pine for both lamellae with and without finger-joints. The manufacturing of finger joints in the lamellae usually implies a decrease in strength, even though the failure mode is 1. Similar decrease factors from clear lamellae to lamellae with finger-joints were found in the characteristic values of the bending strength of pine (0.75) and eucalyptus (0.80), with a slight reduction in the tensile strength of eucalyptus (0.95). However, finger-joint bending strengths were higher than the characteristic strength values of solid wood established in UNIT 1261 [16] and UNIT 1262 [17] for both species (15.5 N/mm2 in pine and 21.4 N/mm2 in eucalyptus, as shown in Table 1).

3.3. Glulam Strength Class Assignment

The European standard EN 14080 provides three ways for assigning strength classes to GLT: (1) from the strength class of the sawn timber; (2) from the properties of both the lamellae and the finger joints; and (3) from the experimental values obtained from full-scale tests on the GLT beams. Since no full-scale tensile tests were performed, only number (1), (2), and (3) methods were analysed in the present work.

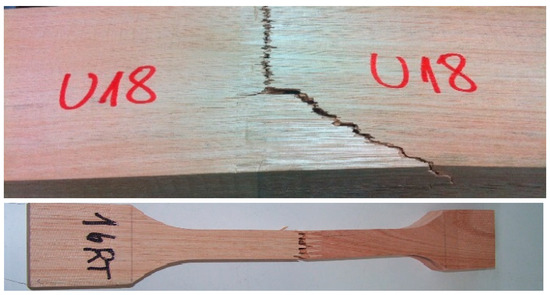

3.3.1. Failure Mode of GLT Beams

The failure mode of the beams was recorded to identify whether the rupture initiation was caused by wood, adhesive, or mixed. Figure 9 shows a typical rupture initiated by wood, Figure 10 depicts a typical adhesive failure and Figure 11 shows a mixed wood-adhesive failure.

Figure 9.

Typical failure initiated by wood failure in GLT bending tests.

Figure 10.

Typical rupture initiated by adhesive failure in GLT bending tests.

Figure 11.

Typical rupture initiated by mixed wood-adhesive failure in GLT bending tests.

The failure mode of pine GLT beams was found to be 100% attributable to wood. A total of 8 of the 41 beams of eucalyptus with the smallest cross-section (75 × 195 mm2) failed due to adhesive or mixed failure. For the highest cross-section (95 × 240 mm2) of eucalyptus, 11 of the 33 specimens failed by adhesive.

3.3.2. Strength Class Assignment from Sawn Timber

The EN 14080 provides a method for assigning GLT strength classes based on the tensile strength class (T) of the sawn timber (lamellae) and the bending strength of the finger joints (fm,j,k). In this work, the strength classes of the sawn timber were obtained only from bending tests. Consequently, the relations between the C and T strength classes given by EN 14080 were used. Table 5 summarises the relationship between the C and T strength classes, the bending strength of the finger joints, and the data required for the assignment of the glulam strength class (GL).

Table 5.

Relationship between C and T strength classes and requirements for the assignment of the glulam class.

As shown in Table 5, despite the correlation between C14 and T8, and C20 with T12, the required values of the finger joints are not included in the standard or the corresponding glulam strength classes. The bending strength of the finger joint was higher than that required by the standard in both species (Table 4). However, the strength class of the eucalyptus lamellae (C20) limited the assignment of the GLT to a GL20h strength class. For pine, no GLT class assignment was possible because the minimum required C16 for the lamellae was not reached. This finding suggests that the method does not provide an optimal class assignment for these two species. However, if the strength classes of the lamellae were obtained from mechanical grading instead from visual grading, a strength class assignment for GLT could be determined.

3.3.3. Strength Class Assignment from Full-Scale Glulam Bending Tests

The mean and characteristic values of bending strength, modulus of elasticity, and density obtained from full-scale tests on the glulam beams are shown in Table 6. Only the specimens with failure mode of 100% by wood were considered for the calculations.

Table 6.

Summary of the structural properties of GLT for pine and eucalyptus and the strength class assignment.

A comparison of the same cross-section of both wood species revealed that the mean values of density and bending strength were similar, yet the modulus of elasticity was 1.4 times superior for eucalyptus. When comparing the physical and mechanical properties of the two cross-sections of eucalyptus, the largest showed the lower values for the three studied properties. Probably, the low properties of the raw material used for the large cross-section of the GLT beams could explain this finding. The low value of the bending strength in the large cross-section could also be attributed to the influence of the height factor, i.e., as the height of the specimen increases, the bending strength decreases [56].

Using pine timber graded as EC1 (C14), glulam beams of strength class GL20h were obtained. Even if the modulus of elasticity was the governing property, the glulam manufacturing process could hardly improve the overall modulus of elasticity based on the low raw material properties. Thus, the increase in the strength class from sawn timber to GLT could be explained due to the usual heterogeneity of wood (CoVE,0,mean = 17% for glulam) or even by the methodology used to determine the characteristic values of a wood population (set of samples) for sawn timber (EN 384) and GLT (EN 14080).

The bending strength was the governing property for the strength class assessment of eucalyptus. Therefore, eucalyptus graded as EF1 (C20) provided two different strength classes depending on the cross-section, GL28h for the smallest, and GL24h for the largest denoting the height influence on the mechanical properties, consistent with the standards.

4. Conclusions

Pine graded as EC1, according to the visual parameters defined in UNIT 1261, could be assigned to a strength class C14 (EN 338), being the modulus of elasticity (E0,m = 7139 N/mm2) for the governing parameter. Eucalyptus graded as EF1 could be assigned to a strength class C20, with the bending strength (fm,k = 21.4 N/mm2) as the limiting property.

For the same stiffness, Uruguayan pine showed higher density (ρk = 365 kg/m3) compared to the common European softwood. For eucalyptus, ratios between the mechanical properties and the density (ρk = 386 kg/m3) were closer to those of C-strength classes than to D-classes, supporting the correct C-strength class assignment.

For similar density values, the bending strength and modulus of elasticity of eucalyptus sawn timber resulted in 1.4 and 1.7 times higher than those corresponding to pine. Comparison of the physical and mechanical properties versus years of forest rotation showed that eucalyptus provided a better yield than pine.

Even though machine stress grading (MSG) increases the grading yield, the lack of available information regarding species and strength classes obtained by MSG disagrees with the use of different classes than C24 for architects, engineers, and developers, who concentrate the demand for structural timber in this strength class.

While the mechanical properties of eucalyptus are higher than those of pine for the same forest rotation, technological issues, such as the conversion factor of logs into sawn wood products or the drying process, could lead to a worse economic scenario to produce structural hardwood glulam.

Analyses of the failure mode of the finger-joints (0% due to adhesive in pine and 23%–25% in eucalyptus) and of the glulam beams suggest that the manufacturing process for eucalyptus should be different from that for pine. Improvement of the gluing process and analysis of the glue line integrity would be necessary in future research. Considering the three methods provided by EN 14080 for the GLT strength classes assignment, the third, based on full-scale experimental bending tests on the GLT beams showed the best results in terms of the highest strength class obtained for both species; GL20 h for pine (fm,mean,g_kh = 46.1 MPa, E0,mean = 9842 MPa, ρg,k = 466 kg/m3), and GL24 h (fm,g,k = 29.7 MPa, E0,mean,g = 13,783 MPa, ρg,k = 493 kg/m3) and GL28 h (fm,g,k = 25.7 MPa, E0,mean,g = 12,092 MPa, ρg,k = 459 kg/m3) for eucalyptus relying on the cross-section size.

It is worth noting the importance of the European standards in the development of the national standards in this study. A previous decision supported by an international panel of experts suggested adopting the European standard corpus. Nevertheless, local issues, such as species, forest management, or processing and manufacturing technology, must be considered since knowledge is not directly transferable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B., D.G. and L.M.; methodology, V.B., D.G. and C.P.-G.; investigation, D.G. and C.P.-G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.B. and D.G.; writing—review and editing, L.M.; supervision, V.B. and L.M.; project administration, L.M. (ANII project) and V.B. (INIA project); funding acquisition, L.M., V.B. and D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ANII project # PR FSA_1_2013_1_12897—Uruguay; INIA project # FPTA 306—Uruguay, and BASAJAUN Horizon 2020 project # 862942, funded by the European Union.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Ignacio Torino for their technical assistance and the company Raices for the manufacture of beams.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hurtado, C.M.; Sierra, M.A. Professional Workshop in Wood: Structural Efficiency Index for Architecture Students. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE 2023), Oslo, Norway, 19–22 June 2023; pp. 4611–4618. [Google Scholar]

- Basterra, L.-A.; Baño, V.; López, G.; Cabrera, G.; Vallelado-Cordobés, P. Identification and Trend Analysis of Multistorey Timber Buildings in the SUDOE Region. Buildings 2023, 13, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churkina, G.; Organschi, A.; Reyer, C.P.O.; Ruff, A.; Vinke, K.; Liu, Z.; Reck, B.K.; Graedel, T.E.; Schellnhuber, H.J. Buildings as a Global Carbon Sink. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baño, V.; Kies, U.; Romih, P.; Garcia-Jaca, J. Overview of Strategies and Innovations in the European Wood Sector. In Proceedings of the Wood Policy and Innovation Conference 2024: Europe’s Wood Sector as a Driver for the Green and Digital Transition of the Built Environment (WPIC 2024), Tecnalia Research and Innovation & InnovaWood, Brussels, Belgium, 7 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Haisma, R.; Den Boer, E.; Rohmer, M.; Schouten, N.; Björck, C.; Sierra García, M. Impact Scan For Timber Construction In Europe; Metabolic: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Leskinen, P.; Cardellini, G.; González-García, S.; Hurmekoski, E.; Sathre, R.; Seppälä, J.; Smyth, C.; Stern, T.; Verkerk, P.J. Substitution Effects of Wood-Based Products in Climate Change Mitigation; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Iejavs, J.; Skele, K.; Grants, E.; Uzuls, A. Bonding Performance of Wood of Fast-Growing Tree Species Eucalyptus (Eucalyptus Grandis) and Radiata Pine (Pinus Radiata D.Don) with Polyvinyl Acetate and Emulsion Polymer Isocyanate Adhesives. Agron. Res. 2022, 20, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehlmann, U.; Bumgardner, M.; Alderman, D. Recent Developments in US Hardwood Lumber Markets and Linkages to Housing Construction. Curr. For. Rep. 2017, 3, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forest Europe/UNECE/FAO. State of Europe’s Forests 2020; Forest Europe: Zvolen, Slovakia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, M. The Challenge of Strength Grading UK Hardwoods. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov. Ser. II For. Wood Ind. Agric. Food Eng. 2023, 16, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, M.; Gong, M.; Chui, Y.-H. Evaluation of Major Physical and Mechanical Properties of Trembling Aspen Lumber. Materials 2024, 17, 2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Taoum, A.; Kotlarewski, N.; Chan, A.; Holloway, D. Investigating Vibration Characteristics of Cross-Laminated Timber Panels Made from Fast-Grown Plantation Eucalyptus Nitens under Different Support Conditions. Buildings 2024, 14, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.; Moltini, G.; Dias, A.M.P.G.; Baño, V. Machine Grading of High-Density Hardwoods (Southern Blue Gum) from Tensile Testing. Forests 2023, 14, 1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggate, W.; McGavin, R.L.; Outhwaite, A.; Gilbert, B.P.; Gunalan, S. Barriers to the Effective Adhesion of High-Density Hardwood Timbers for Glue-Laminated Beams in Australia. Forests 2022, 13, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MGAP. Anuario Estadístico Agropecuario 2023. Sección 10. Producción Vegetal: Forestación (Agricultural Statistical Yearbook 2023. Section 10. Forests); MGAP: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- UNIT 1261; Madera Aserrada de Uso Estructural—Clasificación Visual—Madera de Pino Taeda y Pino Ellioti (Pinus Taeda y Pinus Elliottii). UNIT: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2018. Available online: https://www.unit.org.uy/normalizacion/norma/100000912 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- UNIT 1262; Madera Aserrada de Uso Estructural—Clasificación Visual—Madera de Eucalipto (Eucalyptus Grandis). UNIT: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2018. Available online: https://www.unit.org.uy/normalizacion/norma/100000942 (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Moya, L.; Domenech, L.; Cardoso, A.; Oneill, H.; Baño, V. Proposal of Visual Strength Grading Rules for Uruguayan Pine Timber. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2017, 75, 1017–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, L.; Cardoso, A.; Cagno, M.; O’Neill, H. Caracterización Estructural de Madera Aserrada de Pinos Cultivados En Uruguay. Maderas. Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2015, 17, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, L.; Pérez Gomar, C.; Vega, A.; Sánchez, A.; Torino, I.; Baño, V. Relación Entre Parámetros de Producción y Propiedades Estructurales de Madera Laminada Encolada de Eucalyptus Grandis. Maderas. Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2019, 21, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, G.; Paganini, F. Mixed Glued Laminated Timber of Poplar and Eucalyptus Grandis Clones. Holz. Roh. Werkst. 2003, 61, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baño, V.; Domenech, L.; Mazzey, C.; Vieillard, T.; Journot, J.B. Hardwood Glulam in Complex Structures: Design and Construction of the MACA Museum in Uruguay. In Proceedings of the Proceedings from the 13th World Conference on Timber Engineering 2023, Oslo, Norway, 19–22 June 2023; p. 4730. [Google Scholar]

- MVOT. Hoja de Ruta Para La Construcción de Vivienda Social de Madera En Uruguay (Roadmap for the Timber Construction Social Housing in Uruguay); MVOT: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- MEVIR. El Hornero Edición Digital No 6; MEVIR: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2024; pp. 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Uzelac Glavinic, I.; Boko, I.; Toric, N.; Louvric Vrankovic, J. Application of Hardwood for Glued Laminated Timber in Europe. J. Croat. Assoc. Civ. Eng. 2020, 72, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Bond, B.; Quesada, H. Producing Structural Grade Hardwood Lumber as a Raw Material for Cross-Laminated Timber: Yield and Economic Analysis. Bioresources 2023, 19, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiaras, S.; Chavenetidou, M.; Koulelis, P.P. A Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis Approach for Assessing the Quality of Hardwood Species Used by Greek Timber Industries. Folia Oecologica 2024, 51, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezu, I.; Ishiguri, F.; Ohshima, J.; Yokota, S. Relationship between the Xylem Maturation Process Based on Radial Variations in Wood Properties and Radial Growth Increments of Stems in a Fast-Growing Tree Species, Liriodendron Tulipifera. J. Wood Sci. 2022, 68, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, B.C. Some Technological Properties of Laminated Veneer Lumber Produced with Fast-Growing Poplar and Eucalyptus. Maderas. Cienc. Y Tecnol. 2016, 18, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, R.; Muñoz, F. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Eight Fast-Growing Plantation Species in Costa Rica. J. Trop. For. Sci. 2010, 22, 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Resquin, F.; Baez, K.; de Freitas, S.; Passarella, D.; Coelho-Duarte, A.P.; Rachid-Casnati, C. Impact of Thinning on the Yield and Quality of Eucalyptus Grandis Wood at Harvest Time in Uruguay. Forests 2024, 15, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussoni, A.; Cabris, J. A Financial Evaluation of Two Contrasting Silvicultural Systems Applicable to Pinus Taeda Grown in North-East Uruguay. South. For. A J. For. Sci. 2010, 72, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubbage, F.; Koesbandana, S.; Mac Donagh, P.; Rubilar, R.; Balmelli, G.; Olmos, V.M.; De La Torre, R.; Murara, M.; Hoeflich, V.A.; Kotze, H. Global Timber Investments, Wood Costs, Regulation, and Risk. Biomass Bioenergy 2010, 34, 1667–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, L.; Laguarda, M.F.; Cagno, M.; Cardoso, A.; Gatto, F.; O’Neill, H. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Loblolly and Slash Pine Wood from Uruguayan Plantations. For. Prod. J. 2013, 63, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 338; Structural Timber. Strength Classes. European Standardisation Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- PrEN 1912:2023; Structural Timber—Strength Classes—Assignment of Visual Grades and Species. CEN TC 124 WG 2: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- EN 408:2010+A1:2012; Timber Structures—Structural Timber and Glued Laminated Timber—Determination of Some Physical and Mechanical Properties; CEN TC 124 WG 1. Test methods. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- EN 14080:2013; Timber Structures—Glued Laminated Timber and Glued Solid Timber—Requirements; CEN TC 124/WG3. Timber structures. Glued laminated timber. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- EN 14358; Timber Structures. Calculation and Verification of Characteristic Values. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- EN 384; Structural Timber. Determination of Characteristic Values of Mechanical Properties and Density. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- Rosa, T.O.; Iwakiri, S.; Trianoski, R.; Terezo, R.F.; Coelho, L.K.; Righez, J.L.B. Static Bending Strength and Stiffness in Juvenile and Adult Wood of Fast-Growing Pinus taeda L. Floresta 2023, 53, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRAM 9662-2; Madera Laminada Encolada Estructural. Clasificación Visual de Las Tablas Por Resistencia. Parte 2: Tablas de Eucalyptus Grandis (Glued Laminated Timber. Visual Strength Grading of Lamellas. Part 2: Eucalyptus Grandis). IRAM: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2013.

- UNE 56546; Clasificación Visual de La Madera Aserrada Para Uso Estructural: Madera de Frondosas. (Visual Strength Grading of Sawnwood: Hardwoods). AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2024.

- Moltini, G.; Íñiguez-González, G.; Cabrera, G.; Baño, V. Evaluation of Yield Improvements in Machine vs. Visual Strength Grading for Softwood Species. Forests 2022, 13, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 14081-1:2005+A1:2011; MPA Certificate of Conformity of the Factory Production Control for Strength Graded Structural Timber with Rectangular Cross Section for Strength Classes up to C30. Certificate of conformity of the factory production control. CE marking. CATG: Lancashire, UK, 2023.

- Dieste, A.; Baño, V.; Cabrera, M.N.; Clavijo, L.; Palombo, V.; Moltini, G.; Cassella, F. Forest-Based Bioeconomy Areas Strategic Products from a Technological Point of View; Universidad de la República de Uruguay: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2018; ISBN 978-9974-0-1629-3. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; ITTO; UN. Forest Product Conversion Factors; FAO, ITTO and United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dieste, A. Plan de Inversiones En Maquinaria y Equipos. (Investment Plan for Machinery and Equipment); Ministerio de Industrias, Energía y Minería: Montevideo, Uruguay, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pagel, C.L.; Lenner, R.; Wessels, C.B. Investigation into Material Resistance Factors and Properties of Young, Engineered Eucalyptus Grandis Timber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 230, 117059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlotzhauer, P.; Kovryga, A.; Emmerich, L.; Bollmus, S.; Van de Kuilen, J.-W.; Militz, H. Analysis of Economic Feasibility of Ash and Maple Lamella Production for Glued Laminated Timber. Forests 2019, 10, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, A.; Baño, V.; Cardoso, A.; Moya, L. Experimental and Numerical Evaluation of the Structural Performance of Uruguayan Eucalyptus Grandis Finger-Joint. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2020, 78, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Bocanegra, A.J.; Majano-Majano, A.; Crespo, J.; Guaita, M. Finger-Jointed Eucalyptus Globulus with 1C-PUR Adhesive for High Performance Engineered Laminated Products. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 135, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segundinho, P.G.A.; Goncalves, F.G.; Gava, G.C.; Tinti, V.P.; Alves, S.D.; Regazzi, A.J. Eficiência da colagem de madeira tratada de Eucalyptus cloeziana F. Muell para produc.o de madeira laminada colada (MLC). Rev. Mater. 2017, 22, e11808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.F.; Segundinho, P.G.d.A.; da Silva, J.G.M.; Gonçalves, F.G.; Lopes, D.J.V.; Silva, J.P.M.; Lopes, N.F.; Mastela, L.d.C.; Paes, J.B.; de Souza, C.G.F.; et al. Eucalyptus-Based Glued Laminated Timber: Evaluation and Prediction of Its Properties by Non-Destructive Techniques. Forests 2024, 15, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pommier, R.; Elbez, G. Finger-Jointing Green Softwood: Evaluation of the Interaction between Polyurethane Adhesive and Wood. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2006, 1, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermoso, E.; Fernández-Golfín, J.I.; Díez, M.R. Analysis of Depth Factor in Pinus Sylvestris L. Structural Timber. For. Syst. 2002, 11, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).