Forests and Their Related Ecosystem Services: Visitors’ Perceptions in the Urban and Peri-Urban Spaces of Timișoara, Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the benefits of the recreational, aesthetic, and spiritual values offered by the urban and peri-urban forests, and what are the negative perceptions around the current management of urban and peri-urban forests?

- (2)

- How could urban and peri-urban forests be better preserved in the future and what solutions do visitors offer toward more sustainable urban and peri-urban ecosystem services?

2. Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

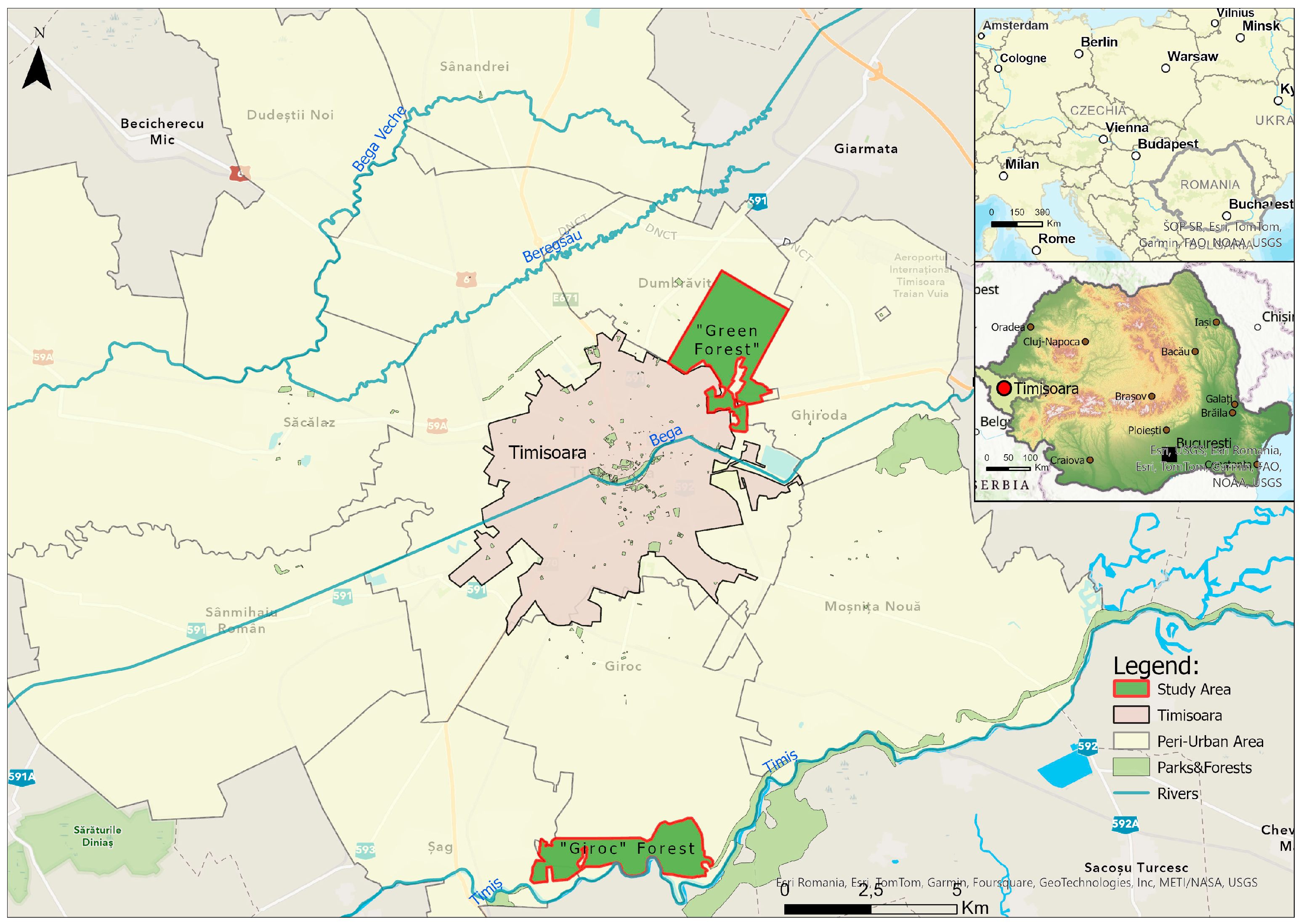

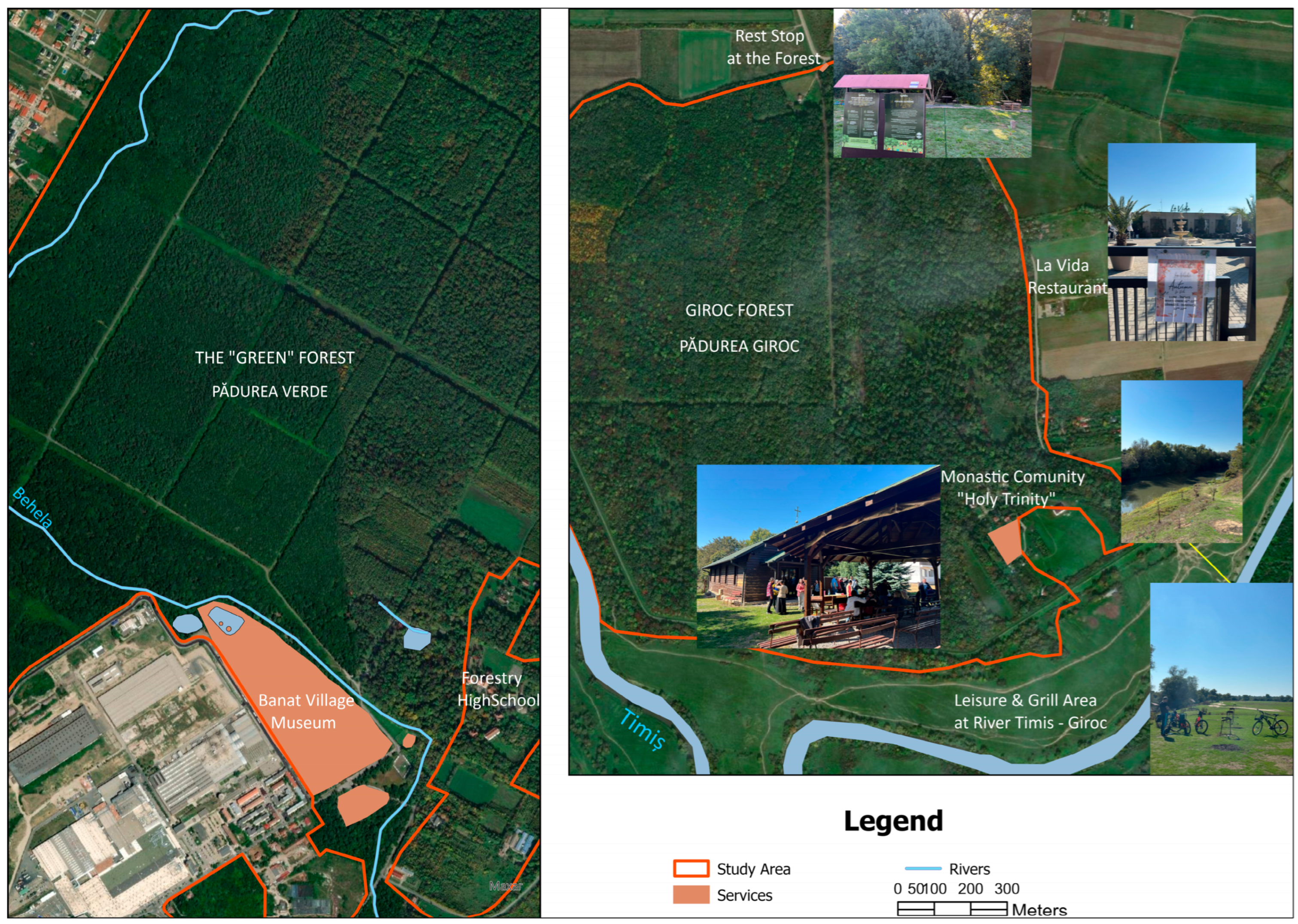

4. Study Area

5. Results

5.1. A Quantitative Overview of Interview Results

5.2. The Benefit of the Ecosystem Values of These Forests, Including the Recreational, Aesthetic and Cultural Values

‘Ah, well, the forest is our ‘green gold’. Well, we cannot live without forests—they offer air, health, peace, and protection’. (I5)

‘Especially when you come from a city like this, out of a continuous crowd, running from one place to another, you enter the forest, it calms you down. You don’t feel the passing of time so much’. (I9)

‘So in the forest, my wife says about me, when you go into a forest, your face lights up and you change and I don’t know, it’s a favorable environment. What’s important is that the forest is an ozone layer, it’s a breath of oxygen produced by trees’. (I34)

‘This forest is safe in every way, physically, spiritually and psychologically’. (I16)

‘The forest is an oasis of normality, of naturalness, of tranquility and a manager of memory’. (I6)

‘We watch shooting stars in August when the Perseids are on. We get a bunch of our friends together, and we come out in the field, where there aren’t so many lights, and we sit and talk. At the beginning of August, there’s a lot of them, and it’s really beautiful’. (I28)

‘I’m coming in this forest for the monastery here at Giroc and, as I said, to discover God more deeply’. (I16)

‘Yes, absolutely, in the strictest sense of the word. It really is a forest spiritual community here. The fact that we have this meal afterward, the mass, the agape, the fact that people get to know each other, we talk to the priests, we talk to the monks’. (I17)

‘There’s a bike path here. I’ve introduced it into my relaxation circuit quite often. I also use the bike path to the border’. (I30)

‘Other than walking, and I have two places, two places where there are fallen trees, in the shade of which you can lie down and pray after prayer’. (I19)

‘The water itself, you can go swimming, maybe fishing, bathing and the forest is beautiful and the forest inside is elegant. In the forest it’s clean; inside you can walk’. (I23)

‘Well, there are trails/bike lanes, some paths in the forest, several, from different trails, I know a few trails that are very well laid out for bicycles’. (I33)

‘Yeah, it’s definitely a much wilder landscape. You can still see animals for example, we saw deer several times, they were even running parallel to us when we were biking’. (I33)

‘The air is not so polluted in this forest than in parks. In the city, even if it is a park, even if there are trees near roads, there is still heat and pollution. The air is cleaner here in the forest’. (I14)

‘The advantages of forests are that there are no people, and you can go if you want peace and quiet. In the forest, you know that you will not bump into too many people; if you do, you can go there, and there will not be anyone there’. (I35)

‘You come here to walk around, not to sit like in a park’. (I1)

‘For me, parks, especially in a city, are a bit of an oasis of greenery, but they are quiet by no means. The forest is that wild world’. (I24)

5.3. Visitors’ Disappointment with the Management Quality of the Forest Areas

‘But sometimes it smells bad, I think it’s coming from the Continental tires factory’. (I1)

‘The only thing is that if you come on foot, as we did, this part of the Continental, this area is not very pedestrian accessible due to Continental’s built area…it is also a polluted area’. (I7)

‘Yeah, this forest (Padurea Verde) is polluted because certain factories are nearby that process certain raw materials’. (I6)

‘I didn’t agree with the festivals in forest areas because just as the animals disturb us when they come into our environment, we disturbed them quite a bit with the music, at least at nights it is much louder music and deafening noises for the animals’. (I2)

‘It’s not always quiet in the area, as Timis is very close, there are monster parties, only parties, parties’. (I18)

‘Noise pollution is a problem in this forest. I think noise pollution is worse than pollution in general’. (I25).

‘Unfortunately, many downed trees, dry on the ground, are not being cleaned up. But there’s much dry wood on the ground which at least could be given to the poor people of Giroc village as heating wood or some old trees could be chopped, but that’s it, the forest not well maintained, I mean you can see it all around the forest’. (I18)

‘We need cleared paths to walk on; there are no fallen trees in the forest but not to see trees fallen on paths’. (I22).

‘Unfortunately, this forest is not very clean. I mean, in general, there’s quite a lot of rubbish on the River Timis crossing this forest’. (I21)

‘I would like there to be some distance away, perhaps a public toilet and a way to be able to have water.’ (I9)

‘I’d like to see police patrols, I’d like to see them on bike, I’d like to see the authorities to do more animations for the citizens out there and let’s know we’re safe’. (I11)

‘Here it is not much police…. And a lot of times a lot of people come in there and get stoned by bad persons. And I’ve seen a lot of people like that, especially at night’. (I36)

‘I would put a barrier here at the embankment, 5 lei per car is not a big amount’. (I14)

‘Nothing is being done against the dogs and there are many of them and at night you can hear them’. (I18)

‘The coyotes or what are those at night when we go to see the stars, the jackals, I don’t know what they are, you can hear them, you don’t know exactly how close you are to them’. (I28)

‘About two or three places where you can take a bath is a place where it’s very deep where I don’t really recommend it as people drowned here a month ago, a little girl and her father’. (I23)

‘That edge of the forest toward Dumbrăvița village was a quiet area, but there some people have thrown construction waste’. (I33)

‘Only that there, right at the entrance to the path, there is a barrier. I do not know if we should not enter there, but I don’t know what its purpose is. I don’t know if that could be removed from there’. (I36)

‘Recently, this forest has been returned to Timișoara City Hall, but authorities are not too interested in the management of the forest’. (I34)

5.4. The Need for Organized Activities in the Forests and Maintaining Forests as Wild

‘Just activities like running competitions, cycling competitions, that’s all, not festivals in forests’. (I1)

‘But I was thinking about, I don’t know, lighter things, like…coming to read in the forest yeah, let’s come and put your hammock somewhere, let’s do some of that lighter stuff. A picnic like Picnic on the river Bega’. (I7)

‘Well, activities of running, walking, jogging for younger and elderly people’. (I8)

‘In fact, after all, just as, for example, here in the Village Museum it is customary to have a folk craftsmen’s fair, so it can be done in the forests of Romania’. (I9)

‘I’m thinking of some workshops but not requiring a lot of materials so that you make a mess or camps, I don’t know, trips for children with trails like this, but that’s about it, not concerts where too many people come’. (I10)

‘You could very well do some of these scouting trails for kids, for reconnaissance. There could even be some activities here, why not set up a volleyball field, mini soccer, a bicycle track, but something not necessarily with motor sports to make noise, to disturb very loudly’. (I13)

‘One could organize for example picnics like they organize now in Otelec village’. (I14)

‘Yes, maybe a direct dialog with the monastery of Șag wouldn’t be a bad thing. I mean a route that could be taken at any time, maybe even a pilgrimage there and back I think it would be very beneficial’. (I16)

‘I think, for example, cleaning activities. At one time we also did with young people, children, we used to go to the side of the road and clean, clean up the rubbish’. (I18)

‘In that place at the entrance to the forest to organize evenings of guitar singing. There and here they could make like a stage to be a stage setting, to be a bonfire’. (I22)

‘Let there be some eco-friendly toilets, let there be a fountain as my friend says, change and find a viable solution to replace the grills, and the shade and benches. Entrance fee to the pier 10 lei per person or 5 lei per person to provide the necessary money. If we take the example of the Serbs, cooking contest, pot cooking, fishing contest, how to, say the cyclist’. (I25)

‘To know that when moving toward a point, to know that I find something there, at the end of the trail, as a form of reward for having traveled a distance and at least an opportunity to drink a cold water is waiting for me there’. (I30)

‘I’d like to keep it a landscape that’s close to the city, but still somewhat wild. You could organize all kinds of bike races or especially or running or something like that, or sporting events. Apart from that I wouldn’t organize for example concerts in the middle of, in the middle of the forest or all that kind of stuff that would lead to degradation of the landscape’. (I33)

6. Discussions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, T.; Lin, Z. Research on Digital Experience and Satisfaction Preference of Plant Community Design in Urban Green Space. Land 2022, 11, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Cirella, G. Urban ecosystem services: Advancements in urban green development. Land 2023, 12, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.R.; Thompson, B.S. Urban Ecosystems: A New Frontier for Payments for Ecosystem Services. People Nat. 2019, 1, 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Elmqvist, T. Ecosystem services in urban landscapes: Practical applications and governance implications. Ambio 2014, 43, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolund, P.; Hunhammar, S. Ecosystem services in urban areas. Ecol. Econ. 1999, 29, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Page, J.; Cong, C.; Barthel, S.; Kalantari, Z. How Ecosystems Services Drive Urban Growth: Integrating Nature-Based Solutions. Anthropocene 2021, 35, 100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Escobedo, F.J.; Cirella, G.T.; Zerbe, S. Edible Green Infrastructure: An Approach and Review of Provisioning Ecosystem Services and Disservices in Urban Environments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 242, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, A.; Mudu, P. How Can Vegetation Protect Us from Air Pollution? A Critical Review on Green Spaces’ Mitigation Abilities for Air-Borne Particles from a Public Health Perspective—With Implications for Urban Planning. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 148605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ren, Z.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Y.; Wang, W.; Bao, G. Efficient Cooling of Cities at Global Scale Using Urban Green Space to Mitigate Urban Heat Island Effects in Different Climatic Regions. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruize, H.; van der Vliet, N.; Staatsen, B.; Bell, R.; Chiabai, A.; Muiños, G.; Higgins, S.; Quiroga, S.; Martinez-Juarez, P.; Aberg Yngwe, M.; et al. Urban Green Space: Creating a Triple Win for Environmental Sustainability, Health, and Health Equity through Behavior Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langemeyer, J.; Wedgwood, D.; McPhearson, T.; Baró, F.; Madsen, A.L.; Barton, D.N. Creating Urban Green Infrastructure Where It Is Needed—A Spatial Ecosystem Service-Based Decision Analysis of Green Roofs in Barcelona. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dudek, T.; Marć, M.; Zabiegała, B. Chemical Composition of Atmospheric Air in Nemoral Scots Pine Forests and Submountainous Beech Forests: The Potential Region for the Introduction of Forest Therapy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berglihn, E.C.; Gomez-Baggethun, E. Ecosystem services from urban forests: The case of Oslomarka, Norway. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 51, 101358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Niemelä, J.; Kotze, D.J. The delivery of Cultural Ecosystem Services in urban forests of different landscape features and land use contexts. People Nat. 2022, 4, 1369–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegetschweiler, K.T.; Wartmann, F.M.; Dubernet, I.; Fischer, C.; Hunziker, M. Urban forest usage and perception of ecosystem services—A comparison between teenagers and adults. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang-Hwan, J.; So-Hee, P.; JaChoon, K.; Taewoo, R.; Lim, E.M.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Preferences for ecosystem services provided by urban forests in South Korea. For. Sci. Technol. 2020, 16, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, M.; Gurney, G.G.; Coulthard, S.; Cumming, G.S. Ecosystem Services, Well-being Benefits and Urbanization Associations in a Small Island Developing State. People Nat. 2021, 3, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.Y.; Zhang, J.; Masoudi, M.; Alemu, J.B.; Edwards, P.J.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Richards, D.R.; Saunders, J.; Song, X.P.; Wong, L.W. A Conceptual Framework to Untangle the Concept of Urban Ecosystem Services. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 200, 103837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Cirella, G.T. Urban Ecosystem Services: New Findings for Landscape Architects, Urban Planners, and Policymakers. Land 2021, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas-Vasquez, D.; Spyra, M.; Jorquera, F.; Molina, S.; Calo, N.C. Ecosystem services supply from peri-urban landscapes and their contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals: A global perspective. Land 2022, 11, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinis, G.; Koutsias, N.; Arianoutsou, M. Monitoring land use/land cover transformations from 1945 to 2007 in two peri-urban mountainous areas of Athens metropolitan area, Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 490, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spyra, M.; Kleemann, J.; Calò, N.C.; Schürmann, A.; Fürst, C. Protection of peri-urban open spaces at the level of regional policy-making: Examples from six European regions. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyra, M.; La Rosa, D.; Zasada, I.; Sylla, M.; Shkaruba, A. Governance of ecosystem services trade-offs in peri-urban landscapes. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattivelli, V. Planning peri-urban areas at regional level: The experience of Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna (Italy). Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, D.; Geneletti, D.; Spyra, M.; Albert, C. Special issue on sustainable planning approaches for urban peripheries. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneletti, D.; La Rosa, D.; Spyra, M.; Cortinovis, C. A review of approaches and challenges for sustainable planning in urban peripheries. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 165, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-C.; Ahern, J.; Yeh, C.T. Ecosystem services in peri-urban landscapes: The effects of agricultural landscape change on ecosystem services in Taiwan’s western coastal plain. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 139, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedblom, M.; Andersson, E.; Borgström, S. Flexible land-use and undefined governance: From threats to potentials in peri-urban landscape planning. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, M. Snow avalanche hazards in the Fagaras massif (southern Carpathians): Romanian Carpathians—Management and Perspectives. Nat. Hazards 2009, 51, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, M.; Onaca, A. Spatio-temporal reconstruction of snow avalanche activity using dendrogeomorphological approach in Bucegi Mountains Romanian Carpathians. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2014, 104, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jula, M.; Voiculescu, M. Assessment of the Annual Erosion Rate along Three Hiking Trails in the Făgăraș Mountains, Romanian Carpathians, Using Dendrogeomorphological Approaches of Exposed Roots. Forests 2022, 13, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossu, C.A.; Iojă, I.C.; Onose, D.A.; Niță, M.R.; Popa, A.M.; Talabă, O.; Inostroza, L. Ecosystem services appreciation of urban lakes in Romania. Synergies and trade-offs between multiple users. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 37, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitincu, C.G.; Niță, M.R.; Hossu, C.A.; Iojă, I.C.; Nita, A. Stakeholders’ involvement in the planning of nature-based solutions: A network analysis approach. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 14, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comberti, C.; Thornton, T.F.; Wylliede Echeverria, V.; Patterson, T. Ecosystem Services or Services to Ecosystems? Valuing Cultivation and Reciprocal Relationships between Humans and Ecosystems. Glob. Environ. Change 2015, 34, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, G.W.; Chan, K.M.; Eser, U.; Gómez-Baggethun, É.; Matzdorf, B.; Norton, B.; Potschin, M. Ethical Considerations in On-Ground Applications of the Ecosystem Services Concept. BioScience 2012, 62, 1020–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, C.M.; Singh, G.G.; Benessaiah, K.; Bernhardt, J.R.; Levine, J.; Nelson, H.; Turner, N.J.; Norton, B.; Tam, J.; Chan, K.M.A. Ecosystem Services and Beyond: Using Multiple Metaphors to Understand Human–Environment Relationships. BioScience 2013, 63, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.; Hochuli, D.F. Defining greenspace: Multiple uses across multiple disciplines. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 158, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegun, O.B.; Ikudayisi, A.E.; Morakinyo, T.E.; Olusoga, O.O. Urban green infrastructure in Nigeria: A review. Sci. Afr. 2021, 14, e01044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncini, F.; Hirth, S.; Mylan, J.; Robinson, C.H.; Johnson, D. Where the wild things are: How urban foraging and food forests can contribute to sustainable cities in the Global North. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 93, 128216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomprou, M.O. Opportunities and Challenges for the Creation and Governance of Productive Landscapes in Urban Transformations: The Case of Klosterøya Urban Fruit Forest Park. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpaidze, L.; Salukvadze, J. Green in the City: Estimating the Ecosystem Services Provided by Urban and Peri-Urban Forests of Tbilisi Municipality, Georgia. Forests 2023, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanesi, G.; Gallis, C.; Kasperidus, H.D. Urban Forests and Their Ecosystem Services in Relation to Human Health. In Forests, Trees and Human Health; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.; Fluehr, J.; McKeon, T.; Branas, C. Urban Green Space and Its Impact on Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jim, C.Y.; Chen, W.Y. Ecosystem services and valuation of urban forests in China. Cities 2009, 26, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotze, D.J.; Lowe, E.C.; MacIvor, J.S.; Ossola, A.; Norton, B.A.; Hochuli, D.F.; Mata, L.; Moretti, M.; Gagné, S.A.; Handa, I.T.; et al. Urban forest invertebrates: How they shape and respond to the urban environment. Urban Ecosyst. 2022, 25, 1589–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schägner, J.P.; Maes, J.; Brander, L.; Paracchini, M.-L.; Hartje, V.; Dubois, G. Monitoring recreation across European nature areas: A geo-database of visitor counts, a review of literature and a call for a visitor counting reporting standard. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 18, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumanapala, D.; Wolf, I.D. Recreational Ecology: A Review of Research and Gap Analysis. Environments 2019, 6, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerkamp, C.J.; Schipper, A.M.; Hedlund, K.; Lazarova, T.; Nordin, A.; Hanson, H.I. A review of studies assessing ecosystem services provided by urban green and blue infrastructure. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 52, 101367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajter Ostoić, S.; Salbitano, F.; Borelli, S.; Verlič, A. Urban forest research in the Mediterranean: A systematic review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 31, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilliers, S.; Cilliers, J.; Lubbe, R.; Siebert, S. Ecosystem services of urban green spaces in African countries-perspectives and challenges. Urban Ecosyst. 2013, 16, 681–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamhamedi, H.; Lizin, S.; Witters, N.; Malina, R.; Baguare, A. The recreational value of a peri-urban forest in Morocco. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, P.L.; Selin, S.; Cerveny, L.; Bricker, K. Outdoor Recreation, Nature-Based Tourism, and Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrish, E.; Watkins, S.L. The relationship between urban forests and income: A meta-analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 170, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Livesley, S.; Escobedo, F.; Morgenroth, J. The Biodiversity of Urban and Peri-Urban Forests and the Diverse Ecosystem Services They Provide as Socio-Ecological Systems. Forests 2016, 7, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wajchman-Świtalska, S.; Zajadacz, A.; Woźniak, M.; Jaszczak, R.; Beker, C. Recreational Evaluation of Forests in Urban Environments: Methodological and Practical Aspects. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.P. Forest landscapes as social-ecological systems and implications for management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 177, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.; Achilles, B.; Merbitz, H. Urbanity and Urbanization: An Interdisciplinary Review Combining Cultural and Physical Approaches. Land 2014, 3, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebble, S.; McLean, J.; Houston, D. Smart urban forests: An overview of more-than-human and more-than-real urban forest management in Australian cities. Digit. Geogr. Soc. 2021, 2, 100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, S.; Sheppard, S.; Condon, P. Urban Forest Indicators for Planning and Designing Future Forests. Forests 2016, 7, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Kroll, C.N.; Nowak, D.J.; Greenfield, E.J. A review of urban forest modeling: Implications for management and future research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 43, 126366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirri, C.; Swanson, H.; Meenar, M. Finding the “Heart” in the Green: Conducting a Bibliometric Analysis to Emphasize the Need for Connecting Emotions with Biophilic Urban Planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Pacheco, C.B.; Villaseñor, N.R. Urban Ecosystem Services in South America: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, L.; De Vreese, R.; Kern, M.; Sievänen, T.; Stojanova, B.; Atmiș, E. Cultural ecosystem benefits of urban and peri-urban green infrastructure across different European countries. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 24, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevianu, E.; Maloș, C.V.; Arghiuș, V.; Brișan, N.; Bǎdǎrǎu, A.S.; Moga, M.C.; Muntean, L.; Rǎulea, A.; Hartel, T. Mainstreaming Ecosystem Services and Biodiversity in Peri-Urban Forest Park Creation: Experience From Eastern Europe. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 618217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vindigni, G.; Mosca, A.; Bartoloni, T.; Spina, D. Shedding Light on Peri-Urban Ecosystem Services Using Automated Content Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Ispas, R.T.; Crețan, R. Recent Urban-to-Rural Migration and Its Impact on the Heritage of Depopulated Rural Areas in Southern Transylvania. Heritage (2571-9408) 2024, 7, 4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdú-Vázquez, A.; Fernández-Pablos, E.; Lozano-Diez, R.V.; López-Zaldívar, Ó. Green space networks as natural infrastructures in PERI-URBAN areas. Urban Ecosyst. 2021, 24, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobedo, F.J.; Giannico, V.; Jim, C.Y.; Sanesi, G.; Lafortezza, R. Urban forests, ecosystem services, green infrastructure and nature-based solutions: Nexus or evolving metaphors? Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 37, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Barbir, J.; Sima, M.; Kalbus, A.; Nagy, G.J.; Paletta, A.; Villamizar, A.; Martinez, R.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Pereira, M.J.; et al. Reviewing the role of ecosystems services in the sustainability of the urban environment: A multi-country analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Creţan, R.; Jucu, I.S.; Hrițcu, A.A. Revitalizing post-communist urban industrial areas: Divergent narratives in the imagining of copper mine reopening and tourism in a Romanian town. Cities 2024, 154, 105379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A.; Anwar, M.M.; Majeed, M.; Fatima, S.; Mehdi, S.S.; Mangrio, W.M.; Elbouzidi, A.; Abdullah, M.; Shaukat, S.; Zahid, N.; et al. Quantifying Landscape and Social Amenities as Ecosystem Services in Rapidly Changing Peri-Urban Landscape. Land 2023, 12, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vejre, H.; Jensen, F.S.; Thorsen, B.J. Demonstrating the importance of intangible ecosystem services from peri-urban landscapes. Ecological Complexity 2010, 7, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, F.; Dolley, J.; Bisht, R.; Priya, R.; Waldman, L.; Randhawa, P.; Scharlemann, J.; Amerasinghe, P.; Saharia, R.; Kapoor, A.; et al. Recognizing peri-urban ecosystem services in urban development policy and planning: A framework for assessing agri-ecosystem services, poverty and livelihood dynamics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2024, 247, 105042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costemalle, V.B.; Candido, H.M.N.; Carvalho, F.A. An estimation of ecosystem services provided by urban and peri-urban forests: A case study in Juiz de Fora, Brazil. Ciência Rural 2023, 53, e20210208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Creţan, R.; Bulzan, R.D. The spatial development of peripheralisation: The case of smart city projects in Romania. Area 2024, 56, e12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bănică, A.; Istrate, M.; Muntele, I. Towards green resilient cities in eastern european union countries. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2020, 12, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekunle, M.F.; Agbaje, B.M.; Kolade, V.O. Public perception of ecosystem service functions of peri—Urban forest for sustainable management in Ogun State. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 7, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, D.C.; Hobbs, R.J. Cultural ecosystem services: Characteristics, challenges and lessons for urban green space research. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 25, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jin, J.; Davies, C.; Chen, W.Y. Urban Forests as Nature-Based Solutions: A Comprehensive Overview of the National Forest City Action in China. Curr. For. Rep. 2024, 10, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baránková, Z.; Špulerová, J. Human-Nature Relationships in Defining Biocultural Landscapes: A Systematic Review. Ekológia 2023, 42, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Brimblecombe, P. Trees and parks as “the lungs of cities”. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 48, 126552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Gozalo, G.; Barrigón Morillas, J.M.; Montes González, D.; Vílchez-Gómez, R. Influence of Green Areas on the Urban Sound Environment. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2023, 9, 746–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; de Vries, S.; Assmuth, T.; Dick, J.; Hermans, T.; Hertel, O.; Jensen, A.; Jones, L.; Kabisch, S.; Lanki, T.; et al. Research challenges for cultural ecosystem services and public health in (peri-)urban environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2118–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensah, C.A.; Andres, L.; Perera, U.; Roji, A. Enhancing quality of life through the lens of green spaces: A systematic review approach. Int. J. Wellbeing 2016, 6, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Van Damme, S.; Uyttenhove, P. A review of empirical studies of cultural ecosystem services in urban green infrastructure. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, K.N.; Herrett, S. Does ecosystem quality matter for cultural ecosystem services? J. Nat. Conserv. 2018, 46, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosanic, A.; Petzold, J. A systematic review of cultural ecosystem services and human wellbeing. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 45, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.; Crețan, R.; Terian, M.I. Landscapes of Watermills: A Rural Cultural Heritage Perspective in an East-Central European Context. Heritage 2024, 7, 4790–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, D.; Spyra, M.; Inostroza, L. Indicators of Cultural Ecosystem Services for urban planning: A review. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 61, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesbitt, L.; Hotte, N.; Barron, S.; Cowan, J.; Sheppard, S.R.J. The social and economic value of cultural ecosystem services provided by urban forests in North America: A review and suggestions for future research. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 25, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielski, M.; Gołos, P.; Stefan, F.; Taczanowska, K. Unveiling the Essential Role of Green Spaces during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond. Forests 2024, 15, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann-Wübbelt, A.; Fricke, A.; Sebesvari, Z.; Yakouchenkova, I.A.; Fröhlich, K.; Saha, S. High public appreciation for the cultural ecosystem services of urban and periurban-forests during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, B.D.; Kirby, C.L. Ecological restoration in urban environments in New Zealand. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2016, 17, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, I. Examining the Role of Green Infrastructure as an Advocate for Regeneration. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 731975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevzati, F.; Veldi, M.; Külvik, M.; Bell, S. Analysis of Landscape Character Assessment and Cultural Ecosystem Services Evaluation Frameworks for Peri-Urban Landscape Planning: A Case Study of Harku Municipality, Estonia. Land 2023, 12, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatarić, D.; Đerčan, B.; Živković, M.B.; Ostojić, M.; Manojlović, S.; Sibinović, M.; Lutovac, M. Can depopulation stop deforestation? The impact of demographic movement on forest cover changes in the settlements of the South Banat District (Serbia). Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 897201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Patuano, A. Multiple ecosystem services of informal green spaces: A literature review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 81, 127849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfas, D.G.; Zagkas, D.T.; Dragozi, E.I.; Zagkas, T.D. Estimating value of the ecosystem services in the urban and peri-urban green of a town Florina-Greece, using the CVM. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Ghimire, P. Assessment of Opportunities and Challenges of Urban Forestry in Nawalparasi District, Nepal. Grassroots J. Nat. Resour. 2019, 2, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fors, H.; Molin, J.F.; Murphy, M.A.; Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C. User participation in urban green spaces—For the people or the parks? Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menconi, M.E.; Palazzoni, L.; Grohmann, D. Core themes for an urban green systems thinker: A review of complexity management in provisioning cultural ecosystem services. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 65, 127355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Silva, R.; Feurer, M.; Morhart, C.; Sheppard, J.P.; Albrecht, S.; Anys, M.; Beyer, F.; Blumenstein, K.; Reinecke, S.; Seifert, T.; et al. Seeing the Trees Without the Forest: What and How can Agroforestry and Urban Forestry Learn from Each Other? Curr. For. Rep. 2024, 10, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Yin, C.; Hua, T. Nature-based solutions, ecosystem services, disservices, and impacts on well-being in urban environments. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 33, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeland, S.; Moretti, M.; Amorim, J.H.; Branquinho, C.; Fares, S.; Morelli, F.; Niinemets, Ü.; Paoletti, E.; Pinho, P.; Sgrigna, G.; et al. Towards an integrative approach to evaluate the environmental ecosystem services provided by urban forest. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 1981–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Morales, B.; Roces-Díaz, J.V.; Kelemen, E.; Pataki, G.; Díaz-Varela, E. Perception of ecosystem services and disservices on a peri-urban communal forest: Are landowners’ and visitors’ perspectives dissimilar? Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 43, 101089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Yuan, C.; Gao, Y.; Shen, Z.; Liu, K.; Huang, Y.; Wei, X.; Liu, L. Integrating perceptions of ecosystem services in adaptive management of country parks: A case study in peri-urban Shanghai, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 60, 101522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianoș, I.; Cocheci, R.M.; Petrișor, A.I. Exploring the Relationship between the Dynamics of the Urban–Rural Interface and Regional Development in a Post-Socialist Transition. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.F.B.; Rodrigues, M.D.A.; Vieira, S.A.; Batistella, M.; Farinaci, J. Perspectives for environmental conservation and ecosystem services on coupled rural-urban systems. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 15, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeraro, T.; Radicchio, B.; Medagli, P.; Arzeni, S.; Turco, A.; Geneletti, D. Integration of Ecosystem Services in Strategic Environmental Assessment of a Peri-Urban Development Plan. Sustainability 2020, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Qian, H. A comprehensive review of the environmental benefits of urban green spaces. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramyar, R. Social-ecological mapping of urban landscapes: Challenges and perspectives on ecosystem services in Mashhad, Iran. Habitat Int. 2019, 92, 102043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, F.; Schulp, C.J.E.; Verburg, P.H.; van Teeffelen, A.J.A. Testing the applicability of ecosystem services mapping methods for peri-urban contexts: A case study for Paris. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 83, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, D.S.; Ikin, K.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Manning, A.D.; Gibbons, P. The Future of Large Old Trees in Urban Landscapes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciesielski, M.; Stereńczak, K. What do we expect from forests? The European view of public demands. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 209, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordóñez-Barona, C. How different ethno-cultural groups value urban forests and its implications for managing urban nature in a multicultural landscape: A systematic review of the literature. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 26, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, L.E.; Urbanek, R.E.; Gregory, J.D. Ecological functions and human benefits of urban forests. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 75, 127707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corine Land Cover. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Open Street Map. Available online: https://www.openstreetmap.org/ (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Geofabrik patform. Available online: https://www.geofabrik.de/data/download.html (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Bryman, A. Integrating quantitative and qualitative research: How is it done? Qual. Res. 2006, 6, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banat Village Museum. Available online: https://muzeulsatuluibanatean.ro/ (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- High School of Forestry and Agriculture “Casa Verde” Timișoara. Available online: https://lcasaverde.ro/index.php/scoala-noastra/despre-noi (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- Plai Festival. Available online: https://www.plai.ro/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Codru Festival. Available online: https://www.codrufestival.ro/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Eco Timis Network. Available online: https://www.eco-timis-network.eu/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

| Respondent Code | Gender | Age | Area of Origin | Scope of Visits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | Male | 40–50 | Peri-urban | Runner |

| I2 | Female | 30–40 | Timișoara N-E | Walking, walking with dogs |

| I3 | Female | 40–50 | Timișoara N-E | Walking, walking with dogs |

| I4 | Male | >70 | Timișoara Center | Pensioner. Visit Museum |

| I5 | Female | >70 | Rural | Pensioner. Visit Museum |

| I6 | Male | 50–60 | Timișoara S-E | Museum PR |

| I7 | Female | 20–30 | Timișoara N-E | Tourism student. First time in the Museum |

| I8 | Female | 30–40 | Timișoara N-E | Walk, run, relax |

| I9 | Male | 20–30 | Timișoara N | Walk with kids |

| I10 | Female | 20–30 | Timișoara N | Walk with kids |

| I11 | Female | >70 | Timișoara Center | Retired. Relaxation. For fresh air |

| I12 | Female | 40–50 | Peri-urban | Relax |

| I13 | Male | 40–50 | Peri-urban | Relax |

| I14 | Male | >70 | Timișoara S | Grilling |

| I15 | Female | 50–60 | Timișoara S | Grilling |

| I16 | Male | 40–50 | Timișoara S-E | For the monastery. Religious visits |

| I17 | Male | 20–30 | Timișoara N-E | For the monastery. Religious visits |

| I18 | Male | 30–40 | Forest inhabitant | Monah |

| I19 | Female | 40–50 | Timișoara Center | For the monastery. Walks after Mass |

| I20 | Male | 30–40 | Timișoara Center | Fishing |

| I21 | Male | 30–40 | Timișoara Center | Fishing |

| I22 | Female | 30–40 | Peri-urban | Bicycling, fishing, barbecue, Timis river |

| I23 | Male | 30–40 | Peri-urban | Bicycling, fishing, barbecue, Timis river |

| I24 | Male | 40–50 | Peri-urban | Bike, barbecue, relax |

| I25 | Male | 50–60 | Timișoara S-V | Bike, barbecue, relax |

| I26 | Female | 60–70 | Timișoara S-E | Barbecue, relaxation |

| I27 | Male | >70 | Timișoara S-E | Barbecue, relaxation |

| I28 | Female | 30–40 | Timișoara S | Restaurant, forest, Perseids |

| I29 | Female | 30–40 | Timișoara S | Bicyclist. Entrance. |

| I30 | Male | 30–40 | Timișoara S | Bicyclist. Entrance. |

| I31 | Male | 20–30 | Rural | Forestry high school graduate |

| I32 | Female | 20–30 | Peri-urban | Student. Walks |

| I33 | Male | 30–40 | Timișoara S | Bike, blanket, picnic |

| I34 | Male | 50–60 | Forest | Forester/forest manager |

| I35 | Female | 20–30 | Timișoara N-E | Cycling, walking |

| I36 | Female | 20–30 | Timișoara Center | Cycling, walking |

| Study Areas | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Green Forest | Giroc Forest | |

| Accessibility | Presence | Yes | Yes |

| Observation | Easy access (road, pedestrian). Lack of cycle paths to the forest | Easy access (especially for cyclists). Roads to Timis—unmaintained. | |

| Landscape biodiversity | Presence | Yes | Yes |

| Observation | Anthropized. Urban Landscape (grid) | Wild. Meadow landscape | |

| Silence | Presence | Less | Yes |

| Observation | The silence can be affected by the proximity of the city and the organization of festivals and concerts. | The silence is disturbed by private events organized on the Timis Meadow. | |

| Recreational services | Presence | Yes | Yes |

| Observation | Banat Village Museum. Restaurant. Forest paths for biking/running/walking. | Restaurant. Footpaths for walking (dike). Recreation barbecue area of the Timis Meadow. | |

| Recreational infrastructure | Presence | Yes | Yes |

| Observation | Lack of bicycle paths. Drinking water sources or toilets can be found in the Village Museum. | Activities: fishing, swimming, barbecue (meals and barbecues), cycling. | |

| Cultural services | Presence | Yes | No |

| Observation | Banat Village Museum | - | |

| Religious services | Presence | Yes | Yes |

| Observation | Church of the Banat Village Museum | “Holy Trinity” monastic community | |

| Tourist services | Presence | Yes | Less |

| Observation | Festivals held in the Museum and inside the forest (Plai, Codru, Festival of Ethnic Groups) | Tourist trail—Eco Timis No. 3 “Timis Meadow—Macedonia Forest Reservation” | |

| Outdoor events | Presence | Yes, irregular | Informal |

| Observation | Organized—Festivals. Concerts | Walks. Recreation barbecue area on the Timis Meadow | |

| Sports services | Presence | Yes | Yes |

| Observation | On forest roads, people go jogging or cycling. | Timis Eco Bike Trail | |

| Educational services | Presence | Yes | No |

| Observation | Forestry High School | - | |

| Commemorative spaces | Presence | Yes | No |

| Observation | Anti-Communist Resistance Monument | - | |

| Commercial services | Presence | Yes | Yes |

| Observation | Shop—Village Museum. Events hall | Restaurant | |

| Landscaped paths | Presence | No | From |

| Observation | Walking is usually on forest roads | Bike path to the forest | |

| Tourist/cycling trails | Presence | No | Yes |

| Observation | - | Eco Trail Timis n.3 | |

| Water course | Presence | Yes | Yes |

| Observation | Behela, a small river with temporary runoff. | Timis River. Important for activities related to fishing, swimming, relaxation, aesthetic value, etc. | |

| Safety issues | Presence | Yes | Yes |

| Observation | Pets. | Stray dogs. Jackals | |

| R: | Nb. of Days/Month in the Forest | Appreciated in the Forest | Amenities (1—Dissatisfied, 5—Satisfied) | Advantages of Urban Forests over Urban Neighborhood Parks | What Other Facilities/Services/Events Should Be Provided in the Forest | Proposed Rules or Restrictions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 8 | Equipping the forest. | 5 | Fewer people; easier way of jogging. | Litter bins; areas with drinking water; running and cycling competitions; no festivals. | ATV and Motorcycle Prohibition. |

| I2 | 30 | Fresh air. Quiet. Dogs walking area. | 2 | Storm protection; clean air. | Paths; a higher level of organization and planning; no festivals. | Restricting access by car. |

| I3 | 30 | Fresh air; silence; dog walking area. | 1 | Fewer people. | Tourist and sports trails. | Restricting access by car. |

| I4 | 2 | Fresh air; silence. | 5 | Fresh air; silence. | Spaces for outdoor activities; concerts. | Restrictions on pets (dogs). |

| I5 | 3 | Beauty of trees. | 5 | Silence. | Spaces for outdoor activities; activities with past practices from different villages. | Fire ban. |

| I6 | 30 | Fresh air; silence; normality; “The village museum at the end of town”. | 4 | Outdoor exhibition (Village Museum). | Restaurant. | Afforestation work. |

| I7 | 1 | The diversity of houses in the Village Museum. | 2 | Fresh air; informative and cultural role. | Museum tour guide; trash bins; picnic areas. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I8 | 1 | Fresh air; feelings of cooling in summertime. | 3 | Fresh air. | Trails; a higher level of organization and planning. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I9 | 3 | Fresh air; feeling of cooling in the summertime; silence. | 3 | Silence. The diversity of vegetation. | Toilets. Drinking water facilities. Cultural festivals. | Restrictions on littering. Fire ban. |

| I10 | 4 | Fresh air; cooling in summertime; silence. | 4 | The wider space. | Toilets; activities for children. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I11 | 2 | Beauty of trees; fresh air. | 4 | Vegetation diversity. | Police patrols; spaces for children; greening activities. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I12 | 1 | Fresh air. | 3 | Silence. | Benches; chairs; sports activities. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I13 | 1 | Silence. | 3 | The wider space; destination. | Camping spaces; tables; benches; litter bins; sports and children’s activities. | Restricting access by car. |

| I14 | 5 | Fresh air. | 2 | Fresh air. | Benches; chairs; picnic tables. | Restricting access by car. |

| I15 | 4 | Trees; fresh air. | 2 | Silence. | Spaces for outdoor activities. | Deforestation restrictions. |

| I16 | 10 | The religious aspect. | 3 | Silence. | Bike paths on the river dike. | Restrictions on noise pollution. |

| I17 | 5 | The religious aspect. | 3 | Silence. | Transportation to the forest; hiking; picnic. | Stray dog restrictions. |

| I18 | 30 | Beauty of trees; silence. | 2 | Silence; forest’s depth. | Paths; litter bins; greening activities. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I19 | 4 | Beauty of trees. | 2 | Silence; fewer people. | Spaces for children. | Restrictions on noise pollution. |

| I20 | 3 | Silence. | 2 | Silence. | Trash bins; fishing competitions. | Restrictions on deforestation. Restrictions on water pollution. |

| I21 | 4 | The cooling air; water; silence. | 3 | Peace; fresh air. | Spaces for children. | Fire ban. |

| I22 | 30 | The silence; beauty of trees. | 2 | Peace; fresh air. | Paths; trash bins; musical activities. | Restricting access by car. |

| I23 | 30 | Fishing; swimming in the river; bike lane. | 3 | Silence. | Litter bins; activities for children. | Restricting access by car. |

| I24 | 2 | Silence; the beauty of trees. | 4 | Silence. | Camping sites; activities for children. | Restricting access by car. Prohibition of ATV, Motorcycle. |

| I25 | 4 | Trees. Water. | 4 | Fresh air. | Toilets; waste bins; drinking water facilities; gastronomic and sporting activities. | Restricting access by car. Prohibition of ATV, Motorcycle. |

| I26 | 1 | Silence; the beauty of trees. | 3 | Silence. | Litter bins; recreational activities. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I27 | 1 | Silence; fresh air. | 3 | Peace. Fresh air. | Litter bins; recreational activities. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I28 | 2 | Beauty of trees; silence. | 5 | The wider space. | Paths; bike lanes. | Hunting restrictions. |

| I29 | 4 | Silence; relaxation. | 5 | The wider space. | Sport trails; paths. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I30 | 4 | Silence; beauty of trees. | 4 | Silence. | Spaces with drinking water; camping. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I31 | 7 | Silence. | 3 | Silence. | Litter bins; recreational activities. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I32 | 2 | Silence. | 4 | Silence. | Barbecue areas; paths; greening; activities for children. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I33 | 2 | Fresh air; beauty of trees. | 5 | Wild landscape. | Sport trails. | Restrictions on littering. Fire ban. |

| I34 | 30 | Peace; relaxation. | 3 | Vegetation diversity. | Barbecue facilities; toilets; paths. | Restricting access by car. |

| I35 | 4 | Silence. | 3 | Fewer people; silence | Benches; trash bins; festivals; concerts. | Restrictions on littering. |

| I36 | 6 | Fresh air; bike lane. | 4 | Peace; fresh air. | Benches; trash bins; festivals. | Restrictions on littering. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crețan, R.; Chasciar, D.; Dragan, A. Forests and Their Related Ecosystem Services: Visitors’ Perceptions in the Urban and Peri-Urban Spaces of Timișoara, Romania. Forests 2024, 15, 2177. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15122177

Crețan R, Chasciar D, Dragan A. Forests and Their Related Ecosystem Services: Visitors’ Perceptions in the Urban and Peri-Urban Spaces of Timișoara, Romania. Forests. 2024; 15(12):2177. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15122177

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrețan, Remus, David Chasciar, and Alexandru Dragan. 2024. "Forests and Their Related Ecosystem Services: Visitors’ Perceptions in the Urban and Peri-Urban Spaces of Timișoara, Romania" Forests 15, no. 12: 2177. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15122177

APA StyleCrețan, R., Chasciar, D., & Dragan, A. (2024). Forests and Their Related Ecosystem Services: Visitors’ Perceptions in the Urban and Peri-Urban Spaces of Timișoara, Romania. Forests, 15(12), 2177. https://doi.org/10.3390/f15122177