Assessing Wildfire Hazard in the Wildland–Urban Interfaces (WUIs) of Central Portugal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Wildland–Urban Interface Definition

2.3. Wildfire Hazard

3. Results

3.1. WUIs in the Central Region

3.2. Wildfire Hazard at Landscape Scale

3.2.1. Wildfire Susceptibility and Probability

3.2.2. Wildfire hazard

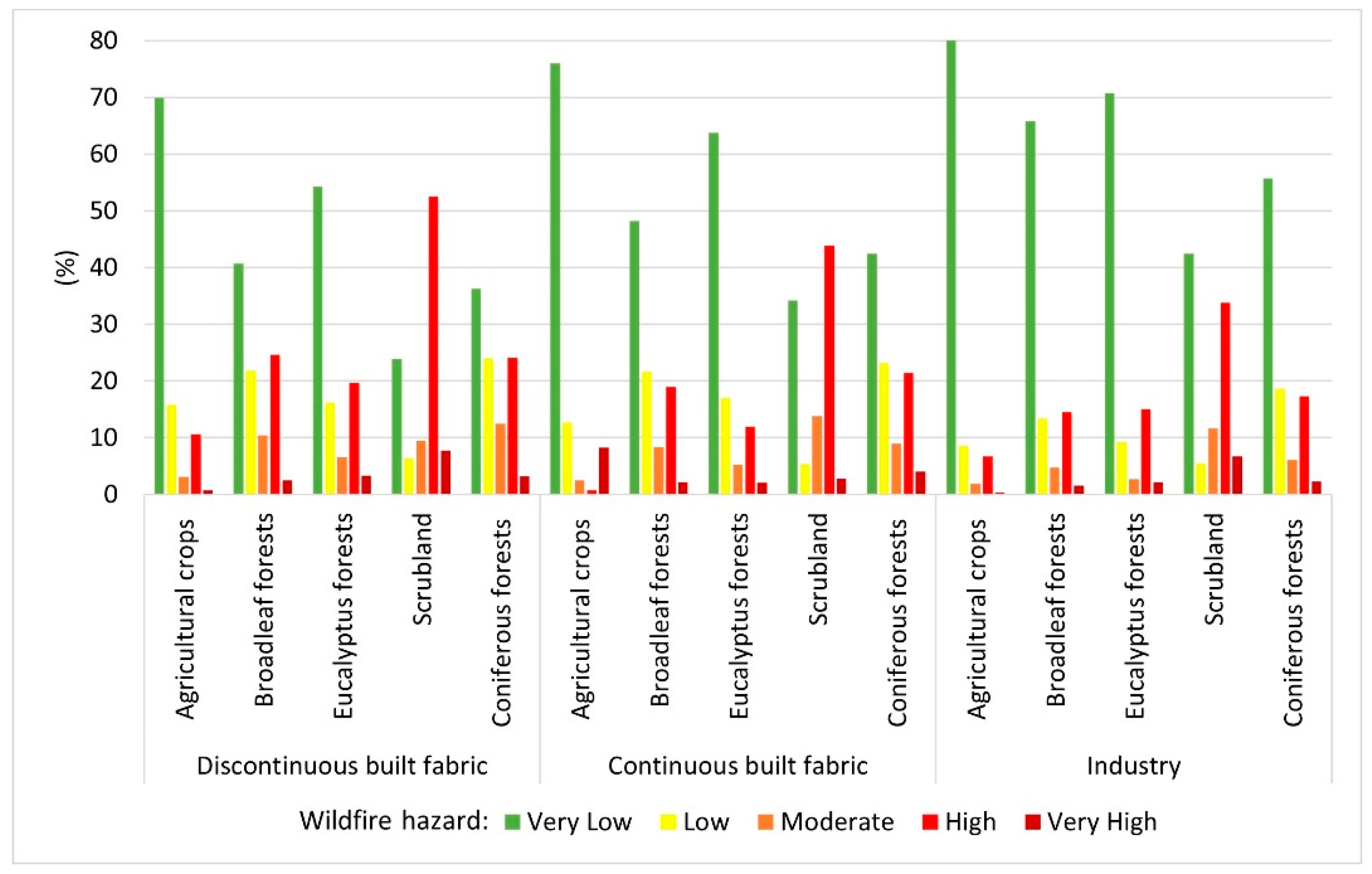

3.3. Wildfire Hazard in WUI in the Central Region

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (i)

- The evaluation of wildfire hazard at the landscape scale, based on Oliveira et al.’s [44] methodology, showed that high and very high classes are dominant in more than half of the study area.

- (ii)

- At the WUI scale, high and very high hazard classes predominate in 4.5% of the segments in direct contact with built-up areas; however, 9% of the WUIs classified as discontinuous urban built-up are in contact with high hazard classes.

- (iii)

- The municipalities with the highest wildfire hazard, at both landscape and WUI scales, are located in the inland and most mountainous areas of the Central Region, characterized by the predominance of shrubland and coniferous forests.

- (iv)

- The use of “the WUI” as a spatial risk analysis unit is an innovative approach in Portugal. It allows the identification of specific locations with higher levels of hazard to wildfire.

- (v)

- This approach could be critical in reducing wildfire risk, since understanding what influences such locations’ susceptibility to wildfires can provide enough detail and guide the design of spatially targeted strategies in the management, preparedness, and mitigation plans.

- (vi)

- LULC management seems to be the basic tool at our disposal to reduce the wildfire hazard at the landscape scale significantly and effectively, as well as the hazard in the WUI areas at the same time.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Balch, J.K.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W.J.; Carlson, J.M.; Cohrane, M.A.; D’Antonio, C.M.; DeFries, R.S.; Doyle, J.C.; Harrison, S.P.; et al. Fire in the earth system. Science 2009, 324, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.P.; Prentice, I.C.; Bloomfield, K.J.; Dong, N.; Forkel, M.; Forrest, M.; Ningthoujam, R.K.; Pellegrini, A.; Shen, Y.; Baudena, M.; et al. Understanding and modelling wildfire regimes: An ecological perspective. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 125008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, V.C.; Hammer, R.B.; Stewart, S.I.; Fried, J.S.; Holcomb, S.S.; McKeefry, J.F. The Wildland-Urban Interface in the United States. Ecol. Appl. 2005, 15, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, D.M.; Romme, W.H. Expansion of the US Wildland-Urban Interface. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiana-Martin, L.; Herrero, G.; Solana, J. A Wildland–Urban Interface Typology for Forest Fire Risk Management in Mediterranean Areas. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radeloff, V.C.; Helmers, D.P.; Kramer, H.A.; Mockrin, M.H.; Alexandre, P.M.; Bar-Massada, A.; Butsic, V.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Martinuzzi, S.; Syphard, A.D.; et al. Rapid growth of the US wildland-urban interface raises wildfire risk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 3314–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bento-Gonçalves, A.; Vieira, A. Wildfires in the wildland-urban interface: Key concepts and evaluation methodologies. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 707, 135592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, J.; Bradley, B.; Abatzoglou, J.; Nagy, R.; Fusco, E.; Mahood, A. Human-started wildfires expand the fire niche across the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 2–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meira Castro, A.C.; Nunes, A.; Sousa, A.; Lourenço, L. Mapping the Causes of Forest Fires in Portugal by Clustering Analysis. Geosciences 2020, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Angerer, J.P.; Wu, X.B. The impacts of wildfires of different burn severities on vegetation structure across the western United States rangelands. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.M.; Martin, N.; Carrega, P.; Andrieu, J.; Adnès, C.; Emsellem, K.; Ganga, O.; Moebius, F.; Tortorollo, N.; Fox, E.A. Increases in fire risk due to warmer summer temperatures and wildland urban interface changes do not necessarily lead to more fires. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, M.I.; Gómez, L.; Vilar, J.; Martínez-Veja, J.; Martín, M.P. Impacts of future land use/land cover on wildfire occurrence in the Madrid region (Spain). Reg. Environ. Chang. 2016, 16, 1047–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampin-Maillet, C.; Jappiot, M.; Long, M.; Bouillon, C.; Morge, D.; Ferrier, J.P. Mapping wildland-urban interfaces at large scales integrating housing density and vegetation aggregation for fire prevention in the South of France. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viedma, O.; Quesada, J.; Torres, I.; De Santis, A.; Moreno, J.M. Fire severity in a large fire in a Pinus pinaster forest is highly predictable from burning conditions, stand structure, and topography. Ecosystems 2015, 18, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellizzaro, G.; Arca, B.; Pintus, G.V.; Ferrara, R.; Duce, P. Wildland-urban interface dynamics during the last 50 years in North East Sardinia. In Modelling Fire Behavior and Risk; Spano, D., Bacciu, V., Salis, M., Sirca, C., Eds.; Nuova Stampa Color Publisher: Turin, Italy, 2012; pp. 249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Technical Commission (ITC). Análise e Apuramento dos Factos Relativos aos Incêndios que Ocorreram em Pedrogão Grande, Castanheira de Pera, Ansião, Alvaiázere, Figueiró dos Vinhos, Arganil, Góis, Penela, Pampilhosa da Serra, Oleiros e Sertã, entre 17 e 24 de Junho de 2017; Final Report; Assembly of the Portuguese Republic: Lisbon, Portugal, 2017; Available online: https://www.parlamento.pt/Documents/2017/Outubro/Relat%C3%B3rioCTI_VF%20.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Independent Technical Commission (ICT). Avaliação dos Incêndios Ocorridos entre 14 e 16 de Outubro de 2017 em Portugal Continental, Relatório Final; Comissão Técnica Independente, Assembleia da República: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018; p. 274. Available online: https://www.parlamento.pt/Documents/2018/Marco/RelatorioCTI190318N.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2020).

- Chas-Amil, M.L.; García-Martínez, E.; Touza, J. Iberian Peninsula October 2017 wildfires: Burned area and population exposure in Galicia (NW of Spain). Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 48, 101623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teague, B.; McLeod, R.; Pascoe, S. Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission; Final Report; Parliament of Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Eavis, P.; Penn, I. California Says PG&E Power Lines Caused Camp Fire that Killed 85, New York Times (15 May 2019). 2018. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/15/business/pge-fire.html (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Spearing, L.; Faust, A.; Kasey, M. Cascading system impacts of the 2018 Camp Fire in California: The interdependent provision of infrastructure services to displaced populations. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mclennan, J.; Paton, D.; Wright, L. At-risk householders’ responses to potential and actual bushfire threat: An analysis of findings from seven Australian post-bushfire interview studies 2009–2014. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 12, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwai, I. What to Read on Australia’s Bushfire Crisis. New York Times. 2020. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/10/world/australia/bushfire.html (accessed on 17 February 2020).

- Efthimiou, N.; Psomiadis, E.; Panagos, P. Fire severity and soil erosion susceptibility mapping using multi-temporal Earth Observation data: The case of Mati fatal wildfire in Eastern Attica, Greece. Catena 2020, 187, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Miranda, E.; Garcia-Gonzalo, J.; Ulloa-Fierro, F.; Weintraub, A.; Barreiro, S. A multicriteria optimization model for sustainable forest management under climate change uncertainty: An application in Portugal. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 269, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.N.; Preißler, J.; Guerrero-Rascado, J.L.; Silva, A.M.; Wagner, F. Forest fire smoke layers observed in the free troposphere over Portugal with a multiwavelength Raman lidar: Optical and microphysical properties. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 421838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paniagua, A. Rurality, identity and morality in remote rural areas in northern Spain. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 35, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, F.P. A necessidade de uma concordância prática entre as normas da classificação dos solos para efeitos de ordenamento do território e da classificação dos solos para efeitos da defesa da floresta contra incêndios: Uma breve reflexão. In Estudos Comemorativos dos XX anos da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade do Porto; Universidade do Porto: Almedina, Portugal, 2018; Volume 1, ISBN 978-972-40-7318-7. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira FP 2018. Algumas notas sobre as alterações ao Decreto-Lei n.º 124/2006, de 28 de junho, operadas pela Lei n.º 76/2017, de 17 de agosto, que define o Sistema de Defesa da Floresta Contra Incêndios. Rev. Eletrónica Direito Público e-Pública 2018, 4, 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, M.L.; Berck, P.; Moritz, P.M.; Batllori, E.; Baldwin, J.G.; Gately, C.K.; Cameron, D.R. Modelling residential development in California from 2000 to 2050: Integrating wildfire risk, wildland and agricultural encroachment. Land Use Policy 2014, 41, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Moreno, J.M.; Camia, A. Analysis of large fires in Europe Medirterranean landscapes: Lessons learned and perspectives. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 294, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedim, F.; Xanthopoulos, G.; Leone, V. Forest Fires in Europe: Facts and Challenges. In Widlfire Hazards, Risks and Disasters; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, D.; Beltran, I. Concepts and ideas of assessing settlement fire vulnerability in the W-UI zone. In Proceedings of the International Workshop Forest Fires in the Wildland-Urban Interface and Rural Areas in Europe, Athens, Greece, 15 May 2003; Available online: www.davidcaballero.com (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Caballero, D. Conclusions of the Third WARM Workshop on Forest Fires in the Wildland-Urban Interface in Europe. Madrid, Spain, 26–27th of May. WARM Project, Final Report. European Commission. 2004. Available online: www.davidcaballero.com (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Lampin-Maillet, C.; Jappiot, M.; Long, M.; Morge, D.; Ferrier, J.P. Characterization and mapping of dwelling types for forest fire prevention. Computers. Environ. Urban Syst. 2009, 33, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Massada, A.; Radeloff, V.C.; Stewart, S.I. Biotic and Abiotic Effects of Human Settlements in the Wildland–Urban Interface. BioScience 2013, 64, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.H.; Thompson, M.P.; Calkin, D.E. A Wildfire Risk Assessment Framework for Land and Resource Management; General Technical Reports RMRS-GTR-315; USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, M.P.; Calkin, D.E.; Finney, M.A.; Gebert, K.M.; Hand, M.S. A risk-based approach to wildland fire budgetary planning. For. Sci. 2013, 59, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darques, R. Mediterranean cities under fire. A Critical Approach Wildland-Urban Interface. Appl. Geogr. 2015, 59, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modugno, S.; Balzter, H.; Cole, B.; Borrelli, P. Mapping regional patterns of large forest fires in Wildland–Urban Interface areas in Europe. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 172, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.M.C.; Alexandre, P.; Campagnolo, M.; Bar-Massada, A.; Radeloff, V.; Silva, P. Defining and mapping the wildland-urban interface in Portugal. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Forest Fire Research, Coimbra, Portugal, 9–16 November 2018; pp. 743–749. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, A. Região Centro de Portugal: Duas décadas de incêndios florestais”. Territorium 2002, 9, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderpour, N.; Rizeei, H.M.; Khakzad, N.; Pradhan, B. Forest fire induced Natech risk assessment: Survey of geospatial technologies. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2019, 191, 106558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Gonçalves, A.; Zêzere, J.L. Reassessing wildfire susceptibility and hazard for mainland Portugal. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 762, 143121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, B.M.; Suliman, B.A.M. Forest fire susceptibility and risk mapping using remote sensing and geographical information systems (GIS). Disaster Prev. Manag. 2007, 16, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohde DCorcoran, J.; Chhetri, P. Spatial forecasting of residential urban fires: A Bayesian approach. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2012, 34, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevinc, V.; Kucuk, O.; Goltas, M.A. Bayesian network model for prediction and analysis of possible forest fire causes. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 457, 117723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.N.; Lourenço, L.; Meira Castro, A.C. Exploring spatial patterns and drivers of forest fires in Portugal (1980–2014). Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 573, 1190–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, F.C. Land use changes and wildfires. In Responses of Forest Ecosystems to Environmental Changes; Teller, A., Mathy, P., Jeffers, J.N.R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Viedma, O.; Arianoutsou, M.; Curt, T.; Koutsias, N.; Rigolot, E.; Barbati, A.; Corona, P.; Vaz, P.; Xanthopoulos, G.; et al. Landscape--wildfire interactions in southern Europe: Implications for landscape management. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2389–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.N. Regional variability and driving forces behind forest fires in Portugal, an overview of the last three decades (1980–2009). Appl. Geogr. 2012, 34, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, R.B.; Radeloff, V.C.; Fried, J.S.; Stewart, S.I. Wildland urban interface housing growth during the 1990s in California, Oregon, and Washington. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2007, 16, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Hong, S.H.; Yang, J. The wildland–urban interface dynamics in the southeastern U.S. from 1990 to 2000. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 85, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, C.; Herrero, G. Overview of policies and practices related to fire ignitions. In Towards Integrated Fire Management-Outcomes of the European Project Fire Paradox; European Forest Institute: Joensuu, Finland, 2010; pp. 35–46. [Google Scholar]

- Tonini, M.; Parente, J.; Pereira, M.G. Global assessment of rural–urban interface in Portugal related to land cover changes. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 18, 1647–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chas-Amil, M.L.; Touza, J.; García-Martínez, E. Forest fires in the wildland–urban interface: A spatial analysis of forest fragmentation and human impacts. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 43, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardille, J.A.; Ventura, S.J.; Turner, M.G. Environmental and social factors influencing wildfires in the upper Midwest, United States. Ecol. Appl. 2001, 11, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Radeloff, V.C.; Keeley, J.E.; Hawbaker, T.J.; Clayton, M.K.; Stewart, S.I.; Hammer, R.B. Human influence on California fire regimes. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 1388–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Zêzere, J.L. Assessing the biophysical social drivers of burned area distribution at the local scale. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 264, 110449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sil, A.; Fernandes, P.M.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Alonso, J.M.; Honrado, J.H.; Pereira, A.; Azevedo, J.C. Farmland abandonment decreases the fire regulation capacity and the fire protection ecosystem service in mountain landscapes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2019, 36, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, A.M.; Pereira, J.M. Wildfire selectivity for land cover type: Does size matter? PLoS ONE 2014, 13, e84760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, M.; Moreira, F.; Casimiro, P.; Vaz, P. Land use and topography influences on wildfire occurrence in northern Portugal. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampin-Maillet, C.; Long-Fournel, M.; Ganteaume, A.; Jappiot, M.; Ferrier, J.P. Land cover analysis in wildland-urban interfaces according to wildfire risk: A case study in the South of France. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 2200–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Pereira, J.M.C.; San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Lourenço, L. Exploring the spatial patterns of fire density in Southern Europe using Geographically Weighted Regression. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 51, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, F.C.; Silva, J.S. Wildfires and landscape dynamics in Portugal: A regional assessment and global implications. In Forest Landscapes and Global Change; Azevedo, J., Perera, A., Pinto, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calviño-Cancela, M.; Chas-Amil, M.L.; García-Martínez, E.D.; Touza, D. Wildfire risk associated with different vegetation types within and outside wildland-urban interfaces. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 372, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakesby, R.A.; Boakes, D.J.; Coelho, C.O.A.; Gonçalves, A.J.B.; Walsh, R.P.D. Limiting the soil degradational impacts of wildfire in pine and eucalyptus forests in Portugal: A comparison of alternative postfire management practices. Appl. Geogr. 1996, 16, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, S.L.; Moghaddas, J.J. Experimental fuel treatment impacts on forest structure, potential fire behavior, and predicted tree mortality in a California mixed conifer forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 215, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.; Taylor, A.; Skinner, C. The influence of fuels treatment and landscape arrangement on simulated fire behavior, Southern Cascade range, California. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 3170–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safford, H.D.; Schmidt, D.A.; Carlson, C.H. Effects of fuel treatments on fire severity in an area of wildland–urban interface, Angora Fire, Lake Tahoe Basin, California. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.C.; Johnson, M.C. Fuel treatment prescriptions alter spatial patterns of fire severity around the wildland–urban interface during the Wallow Fire, Arizona, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 318, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, P.; van Bommel, L.; Gill, A.; Cary, G.J.; Driscoll, D.A.; Bradstock, R.A.; Knight, E.; Moritz, M.A.; Stephens, S.L.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Land management practices associated with house loss in wildfires. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e29212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syphard, A.D.; Brennan, T.J.; Keeley, J.E. The role of defensible space for residential structure protection during wildfires. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2014, 23, 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, A. Defensible Space Optimization for Preventing Wildfire Structure Loss in the Santa Monica Mountains; Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, R.V. Wildfire hazard in the home ignition zone: An object-oriented analysis integrating LiDAR and VHR satellite imagery. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 51, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penman, S.H.; Price, O.F.; Penman, T.D.; Bradstock, R.A. The role of defensible space on the likelihood of house impact from wildfires in forested landscapes of south eastern Australia. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2018, 28, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, P.; Gill, A.M.; Shore, N.; Moritz, M.A.; Dovers, S.; Cary, G.J. Options for reducing house-losses during wildfires without clearing trees and shrubs. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 174, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Rustigian-Romsos, H.; Keeley, J.E. Multiple-Scale Relationships between Vegetation, the Wildland–Urban Interface, and Structure Loss to Wildfire in California. Fire 2021, 4, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Keeley, J.E. Factors associated with structure loss in the 2013–2018 California wildfires. Fire 2019, 2, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braziunas, K.H.; Seidl, R.; Rammer, W.; Turner, M.G. Can we manage a future with more fire? Effectiveness of defensible space treatment depends on housing amount and configuration. Landsc. Ecol. 2021, 36, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, P.M.; Stewart, S.I.; Mockrin, M.H.; Keuler, N.S.; Syphard, A.D.; Bar-Massada, A.; Clayton, M.; Radeloff, V.C. The relative impacts of vegetation, topography and spatial arrangement on building loss to wildfires in case studies of California and Colorado. Landsc. Ecol. 2016, 31, 415–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, P.M.; Stewart, S.I.; Keuler, N.S.; Clayton, M.K.; Mockrin, M.H.; Bar-Massada, A.; Syphard, A.D.; Radeloff, V.C. Factors related to building loss due to wildfires in the conterminous United States. Ecol. Appl. 2016, 26, 2323–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syphard, A.D.; Rustigian-Romsos, H.; Mann, M.; Conlisk, E.; Moritz MAckerly, D. The relative influence of climate and housing development on current and projected future fire patterns and structure loss across three California landscapes. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 56, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classes | 1995 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2018 | 1995/2018 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % | Change (%) | |

| Artificial Territory | 1161 | 4.1 | 1475.4 | 5.2 | 1522.2 | 5.3 | 1546.3 | 5.4 | 1578.5 | 5.5 | 36% |

| Agriculture | 5252.3 | 18.5 | 6373 | 22.4 | 6361 | 22.3 | 6104.8 | 21.4 | 6141 | 21.6 | 17% |

| Agriculture with natural and semi-natural spaces | 705.6 | 2.5 | 431.9 | 1.5 | 443.2 | 1.6 | 472.8 | 1.7 | 501.1 | 1.8 | −29% |

| Pasture land | 2963.1 | 10.4 | 1354.8 | 4.8 | 1316 | 4.6 | 1460.6 | 5.1 | 1184.7 | 4.2 | −60% |

| Agroforestry areas—Holm oak/Cover | 364 | 1.3 | 359.8 | 1.3 | 359.7 | 1.3 | 355.3 | 1.2 | 358.5 | 1.3 | −2% |

| Other agroforestry areas | 16.2 | 0.1 | 19.6 | 0.1 | 19.6 | 0.1 | 18.4 | 0.1 | 19.1 | 0.1 | 93% |

| Agroforestry areas—other oaks | 39.9 | 0.1 | 49.3 | 0.2 | 49.2 | 0.2 | 46.7 | 0.2 | 48.6 | 0.2 | 22% |

| Cork oak and holm oak forests | 712.1 | 2.5 | 805.8 | 2.8 | 803.9 | 2.8 | 819.8 | 2.9 | 842.7 | 3.0 | 35% |

| Forests of other oaks | 834.2 | 2.9 | 921.2 | 3.2 | 919.6 | 3.2 | 929.2 | 3.3 | 945.5 | 3.3 | 13% |

| Other broadleaf forests | 750.7 | 2.6 | 837.1 | 2.9 | 830.8 | 2.9 | 836.2 | 2.9 | 863.9 | 3.0 | 15% |

| Eucalyptus forests | 3251.6 | 11.4 | 4275.6 | 15.0 | 4390.8 | 15.4 | 4635.2 | 16.3 | 4906.6 | 17.2 | 51% |

| Forests of invasive species | 0.5 | 0.0 | 113 | 0.4 | 112.5 | 0.4 | 111.3 | 0.4 | 115 | 0.4 | 21769% |

| Maritime pine forests | 8116.6 | 28.5 | 6911.9 | 24.3 | 6795.6 | 23.9 | 6545.4 | 23.0 | 6364.2 | 22.4 | −22% |

| Forests of other coniferous trees | 128.5 | 0.5 | 225.3 | 0.8 | 226.2 | 0.8 | 222.4 | 0.8 | 234.7 | 0.8 | 165% |

| Scrubland | 3596 | 12.6 | 3714.8 | 13.1 | 3713.3 | 13.0 | 3763.2 | 13.2 | 3774.9 | 13.3 | 5% |

| Sparse vegetation | 187.3 | 0.7 | 190.8 | 0.7 | 189.7 | 0.7 | 236.6 | 0.8 | 182.6 | 0.6 | −2% |

| Wetlands and others | 382.5 | 1.3 | 402.6 | 1.4 | 408.5 | 1.4 | 357.7 | 1.3 | 400.4 | 1.4 | 5% |

| Type of Infrastructure | WUI Type | Code and Name in Land Use Land Cover Map 2018 |

| CBA (Continuous built-up area) | 1.1.1.1 Continuous built-up area, predominantly vertical | |

| 1.1.1.2 Continuous built-up area, predominantly horizontal | ||

| DBA (Discontinuous Built-up area) | 1.1.2.1 Discontinuous built-up area | |

| 1.1.2.2 Sparse discontinuous built-up area | ||

| 1.1.3.1 Parking areas and sites | ||

| 1.1.3.2 Empty spaces without construction | ||

| 1.2.3.1 Agricultural facilities | ||

| 1.5.3.1 Areas under construction | ||

| 1.5.2.2 Rubbish and scrap | ||

| 1.6.2.1 Campsites | ||

| 1.6.4.1 Cemeteries | ||

| 1.6.5.1 Other tourist facilities and equipment | ||

| 1.7.1.1 Parks and gardens | ||

| Industry | 1.2.1.1 Industry | |

| 1.2.2.1 Trade | ||

| 1.3.1.2 Non-renewable energy production infrastructure | ||

| 1.3.2.2 Waste and wastewater treatment infrastructure | ||

| 1.6.1.2 Sports facilities | ||

| 1.6.2.2 Leisure facilities | ||

| Road Network | 1.4.1.1 Road network and associated spaces |

| Hazard Classes | Hazard Scores | Success Curve Trend | Class Area (%) | Burnt Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very High | 0.101–1.597 | y = 2.3106x + 8 × 10−6 | 21.5 | 50 |

| High | 0.032–0.101 | y = 1.8899x + 0.1052 | 28.5 | 48.5 |

| Moderate | 0.027–0.032 | y = 0.1584x + 0.9016 | 6.3 | 1.1 |

| Low | 0.021–0.027 | y = 0.0215x + 0.9798 | 11.5 | 0.4 |

| Very low | 0.009–0.021 | y = 0.0063x + 0.994 | 32.2 | 0 |

| Altitude (m) | LRi (1975–2019) |

|---|---|

| 0–100 | 0.365 |

| 100–200 | 0.69 |

| 200–300 | 1.02 |

| 300–400 | 1.06 |

| 400–500 | 1.127 |

| 500–600 | 1.375 |

| 600–700 | 1.417 |

| 700–800 | 1.486 |

| 800–1000 | 1.572 |

| 1000–1500 | 1.847 |

| 1500–2000 | 0.895 |

| Slopes (°) | LRi (1975–2019) |

|---|---|

| 0–5 | 0.454 |

| 05–10 | 0.716 |

| 10–15 | 0.92 |

| 15–20 | 1.095 |

| >20 | 1.211 |

| Classes | 1995 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2018 | Weighted Average LRi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial | 0.066 | 0.079 | 0.083 | 0.281 | 0.087 | 0.103 |

| Agriculture | 0.476 | 1.185 | 0.743 | 0.715 | 0.759 | 0.692 |

| Agriculture with natural and semi-natural spaces | 0.231 | 0.332 | 0.256 | 0.370 | 0.240 | 0.270 |

| Pasture land | 0.412 | 1.208 | 0.657 | 0.364 | 0.563 | 0.584 |

| Agroforestry areas—Holm oak/cover | 2.494 | 6.110 | 2.417 | 1.279 | 0.762 | 2.646 |

| Other agroforestry areas | 0.238 | 0.015 | 0.132 | 0.081 | 0.011 | 0.142 |

| Agroforestry areas—other oaks | 0.152 | 0.405 | 0.212 | 0.178 | 0.000 | 0.190 |

| Cork oak and holm oak forests | 0.658 | 2.655 | 0.428 | 0.312 | 0.413 | 0.809 |

| Forests of other oaks | 0.853 | 0.648 | 0.531 | 0.207 | 0.037 | 0.590 |

| Other broadleaf forests | 1.499 | 3.471 | 1.845 | 0.911 | 0.721 | 1.696 |

| Eucalyptus forests | 0.593 | 0.597 | 0.926 | 1.367 | 0.355 | 0.753 |

| Forests of invasive species | 0.771 | 0.394 | 0.914 | 1.394 | 1.217 | 0.878 |

| Maritime pine forests | 0.000 | 0.397 | 0.887 | 2.297 | 0.243 | 0.591 |

| Forests of other coniferous trees | 1.090 | 0.533 | 0.975 | 1.526 | 1.548 | 1.089 |

| Scrubland | 0.300 | 0.500 | 0.530 | 0.588 | 0.228 | 0.412 |

| Sparse vegetation | 2.035 | 3.240 | 2.734 | 1.344 | 1.472 | 2.213 |

| Wetlands and others | 0.326 | 0.863 | 0.211 | 0.240 | 0.211 | 0.351 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nunes, A.N.; Figueiredo, A.; Pinto, C.; Lourenço, L. Assessing Wildfire Hazard in the Wildland–Urban Interfaces (WUIs) of Central Portugal. Forests 2023, 14, 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14061106

Nunes AN, Figueiredo A, Pinto C, Lourenço L. Assessing Wildfire Hazard in the Wildland–Urban Interfaces (WUIs) of Central Portugal. Forests. 2023; 14(6):1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14061106

Chicago/Turabian StyleNunes, Adélia N., Albano Figueiredo, Carlos Pinto, and Luciano Lourenço. 2023. "Assessing Wildfire Hazard in the Wildland–Urban Interfaces (WUIs) of Central Portugal" Forests 14, no. 6: 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14061106

APA StyleNunes, A. N., Figueiredo, A., Pinto, C., & Lourenço, L. (2023). Assessing Wildfire Hazard in the Wildland–Urban Interfaces (WUIs) of Central Portugal. Forests, 14(6), 1106. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14061106