Abstract

The prevalence of atopic dermatitis (AD) has increased globally, regardless of age, and preschool children with AD experience greater levels of atrophy, depression, and anxiety. A home with AD experiences considerable stress as well, which affects family life, parenting, and spousal relationships. The provision of forest healing has a positive effect on symptom improvement, psychological stability, and recovery from depression. This study aimed to investigate psychological changes by providing a forest healing camp for atopic children and their families. The RCMAS, which can measure a child’s anxiety, and the K-PSI-SF, which can measure parenting stress, were used as psychological scales. The results showed that the total RCMAS significantly decreased by 2.05 points before and after the forest camp. K-PSI-SF scores also decreased by 8.63 points before and after the forest camp. Both RCMAS and K-PSI-SF, before and after the two-night and three-day program, decreased significantly compared to the difference in their total scores before and after the one-night and two-day program. The anxiety of atopic children and the stress of parenting was found to have decreased through forest camps. We hope that the system and forest healing programs will be established to care for atopic children and their families.

1. Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD), characterized by eczema disorder, erythema, and pruritus, is a common inflammatory skin disease that affects 15%–20% of children and 1%–3% of adults worldwide [1,2]. With the advent of modern society, environmental diseases have increased due to industrialization and westernization, and among them, the prevalence of atopic dermatitis has increased in most countries, regardless of age. As compared to data obtained in 1995 in Korea, in 2010, the prevalence of atopic dermatitis had increased 2.2 times (9.2% to 20.6%) in the 6–7 years age group and 3.2 times (4.0% to 12.9%) in the 13–14 years age group. AD is a chronic and recurrent inflammatory disease that begins during infancy or childhood. The incidence rate is 45% in children during the first six months of life and 60% in children between the first six months and five years of age [3]. Although most AD onset occurs in infancy, it can occur at any age, and environmental factors and psychosocial stresses cause exacerbation of AD [4,5,6], which is considered one of the most burdensome skin diseases [7].

Preschoolers with AD have a reduced quality of life [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16], while infants with AD show chronic itchiness and scratching, mood changes, and sleep disturbances [8], and disturb their sleep by scratching [17,18]. This makes it more difficult to fall asleep and leads to frequent waking up at night, less overall sleep time, and hypersensitivity during the day [19,20]. In addition, the degree of atrophy, depression, and anxiety is severe compared to that in children without AD, and children afflicted with the disease face a high level of tension or a tendency to depend, which affects social development, such as peer relationships [21,22].

The fact of a child suffering from AD affects relationships within the family, parenting, and spouses [23]. Not only children with AD, but also their parents get an average of 1–2 h less sleep than the parents of children unaffected by AD [19], and mothers experience more pain (mothers of children with AD: 85%, mothers of children with controls: 31%), lack of social support (34% vs. 65%), and experience financial burden and social isolation (27% vs. 65%) [24]. Mothers of children with AD experience more stress than those caring for children with insulin-dependent diabetes [19]. AD patients experienced more anger [25,26], depression [27], and anxiety [10,26,28] than the general population. In addition to physical discomfort and pain, adults who experience AD have reported serious consequences for their personal, social, and daily lives [12], and these side effects may be greater than other skin symptoms [29].

The Korea Forest Service has defined forest healing as activities aimed at restoring, maintaining, and promoting health, such as recharging and medical activities, including rehabilitation and counseling using various physical and environmental factors existing in the forest [30]. Forest healing has beneficial effects, such as stress reduction [31,32,33,34,35,36], cognitive recovery [37], and decreasing depression [31,38,39] and cardiovascular diseases [33]. Terpenes released from cypress, Korean pine, cedar, and pine reduce the concentration of cortisol in the body, the hormone that causes stress. It has also been reported that negative ions emitted from forests have a sterilizing effect on some pathogens in the air and that they are absorbed into the body through the skin and respiration to promote metabolism [39]. In addition, the immunological effects of forest healing on pediatric environmental diseases have been proven to improve the symptoms in children with asthma and atopic dermatitis [33,40], increase disease awareness [41], and help in decreasing immune imbalance [41].

A forest-healing program was designed and developed by a forest-healing instructor, according to the gender, age, disease, occupational characteristics, and purpose of the participant. The program was constructed by selecting appropriate healing factors and therapies in consideration of the effects and spatial aspects to be provided to the participants.

Currently, forest healing programs for atopic children exist, although, for families, they are limited to the purpose of knowledge transfer programs, such as education and management programs for atopic children. The Atopic Forest Camp, conducted by the Post Office Public Service Foundation, was initiated to relieve the stress of children suffering from atopic dermatitis and their families. The program was constructed using physical healing resources suitable for the characteristics of each healing forest. Unlike other programs, it has the advantage of being an experience that the children and their families can share together, instead of merely being a knowledge transfer program. However, there is a disadvantage in that the programs conducted in each healing forest are different, and one questionnaire is used for each child and caregiver.

Until now, programs that provide forest healing to children with atopic dermatitis and information on atopy to their families have been mainly used, while the programs and social systems for resolving the stress experienced by families of atopic children are insufficient. Through this study, we have observed psychological changes in caregivers as well as children with atopic dermatitis, and we intend to verify the effects of forest healing through a multi-year study from 2018 to 2021. Based on the research results, we provide basic data that can be used for forest healing, not only for children with atopic dermatitis but also for their caregivers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Method

This study was conducted with 893 atopic children and 766 caregivers, who completed the survey without omission or duplication, and who participated in the atopic forest camp conducted by the Post Office Public Interest Foundation (POPI) between 2018 and 2021. In the case of caregivers, a total of 766 people participated: 471 people in the one-night, two-day program and 295 people in the two-night, three-day program. Of the 893 children who participated in the study, 612 participated in the one-night, two-day program, and 281 participated in the two-night, three-day program.

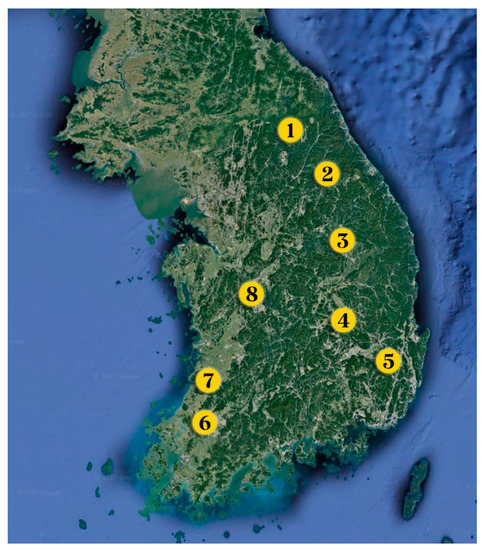

From 2018 to 2020, the program was conducted as a one-night and two-day program, and in 2021 as a two-night, three-day program, and the SoopCheWon and forest healing centers that were implemented in each year are as follows. In 2018: Chilgok SoopCheWon; 2019: Chilgok SoopCheWon and Hoengseong SoopCheWon; 2020: Hoengseong SoopCheWon, Jangseong SoopCheWon, Cheongdo SoopCheWon, and the National Forest Healing Center were surveyed; in 2021: Naju SoopCheWon, National Forest Healing Center, Cheongdo SoopCheWon, Chuncheon SoopCheWon, Chilgok SoopCheWon, and Hoengseong SoopCheWon were surveyed.

2.2. Study Subjects

A questionnaire was administered before and after participation in the lodging-type forest healing program. When answering the pre–post questionnaire, 893 children with atopic dermatitis and 766 caregivers were selected when only subjects with one answer per question were selected, excluding questionnaires that were either checked or not answered (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject general characteristics.

2.3. Study Site

The SoopCheWon and Forest Healing Center, which were used as research sites, are recreational facilities for forest healing operated by the Korea Forest Welfare Promotion Agency and are eco-friendly spaces that consider the safety and convenience of users and the efficiency of facility management. There are a total of seven SoopCheWon, located in Chuncheon, Cheongdo, Hoengseong, Naju, Jangseong, Chilgok, and Daejeon, and the Forest Healing Center is located in Yeongju. The locations and characteristics of the facilities where the experiments were conducted each year in this study are shown in Figure 1 and Table 2.

Figure 1.

SoopCheWon and Forest Healing Center locations. (1: Chuncheon SoopCheWon, 2: Hoengseong SoopCheWon, 3: Forest Healing Center, 4: Chilgok SoopCheWon, 5: Cheongdo SoopCheWon, 6: Naju SoopCheWon, 7: Jangseong SoopCheWon, 8: Daejeon SoopCheWon).

Table 2.

Study site location and characteristics.

2.4. Forest Healing Program

A forest healing program, operated according to the regional characteristics of each institution, was utilized. The two-day, one-night program from 2018 to 2020 was conducted at five locations (National Forest Healing Center, Hoengseong SoopCheWon, Chilgok SoopCheWon, Jangseong SoopCheWon, Cheongdo SoopCheWon) (Table 3). In 2021, it was held as a two-night, three-day program at eight locations (National Forest Healing Center, Hoengseong SoopCheWon, Chilgok SoopCheWon, Jangseong SoopCheWon, Cheongdo SoopCheWon, Daejeon SoopCheWon, Chuncheon SoopCheWon, and Naju SoopCheWon) (Table 4). In addition, it was difficult to know which program was conducted just by looking at the name of the forest healing program, so the classification according to the forest healing program activities of Park (2021) was indicated by a reference. In addition to this program, factors that affect forest healing include those found in the natural environment. The natural environment in the forest plays a positive role in humans’ lives, whereby it is different from the daily environment in the city [42]. However, it also includes a variety of factors that are difficult to control, such as temperature, humidity, and wind.

Table 3.

Schedule of forest healing programs for one night and two days for each institution from 2018 to 2020.

Table 4.

Schedule of forest healing programs for two nights and three days for each institution in 2021.

2.5. Measuring Tool

To determine psychological changes in the atopic children and caregivers before and after participating in the forest healing program, the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMASS) and the Korean version of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI-SF: Parenting Stress Index-Short Form) were used. Time of preparation for the inspection sheet, including the measurement index before and after the forest healing program, was included. Additionally, the forest healing instructor provided an explanation to the participants about how to fill out the test sheet and to enhance their understanding of the measurement index.

The RCMASS was developed by Taylor (1951), and Reynolds (1978) modified it to suit children and created a revised version of the Children’s Anxiety Scale. Based on the revised and supplemented version of the Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale, which was adapted by Choi and Jo (1990) to fit the Korean context, Park et al. (2005) analyzed factors, including 9 fictional items and 28 anxiety items. This study used a scale consisting of 37 items. This is a reliable and valid tool to measure characteristic anxiety in children and adolescents as it can self-report anxiety that cannot be easily observed and revealed with self-report tests. The subdomain consists of four categories–excessive worry, sensitivity, physical and sleep problems, negative emotions, and attention problems–while the response categories are “Yes” (one point) and “No” (zero points). The higher the score, the higher the child’s anxiety.

The K-PSI-SF is a scale developed by Abidin (1995) to measure parenting stress because extreme parental stress related to child-rearing negatively affects both the parents and children. This scale is designed to measure the relative amount of stress in parent-child relationships as a tool for determining and examining parenting-related stress experienced by parents. It was translated into Korean through a three-step translation process recommended for scale translation by clinical psychologists proficient in foreign languages. Subsequently, 36 items, selected by Jeong et al. (2008) to suit the Korean context, were chosen and a shortened version of the Korean version of the parenting stress test was developed. This is a parent-report format that measures the level of parenting stress experienced by parents of children aged 1 to 12 years. It consists of three domains: parental pain, parent-child dysfunctional interaction, and difficult children. Parenting stress was rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” (one point) to “very much” (five points). It consisted of a total of 36 questions, with 12 questions for each subdomain, and the higher the score, the higher the stress on the parents.

2.6. Result Analysis Method

The questionnaires conducted before and after the atopic forest camp were analyzed, and only the questionnaires that checked one answer per question were extracted and included, excluding questionnaires with duplicate checks or non-responses. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the mean and standard deviation of each scale. After setting the control group before participating in the forest camp and the experimental group after participating in the forest camp, the change in the children’s RCMASS and the change in the caregiver’s PSI-SF were tested using a paired t-test, and the analysis was performed using the SPSS 20.0 program. Hedges’ g was calculated to derive the effect size of forest healing according to the number of days the children and caregivers stayed. Hedges’ g can derive a calibrated standardized average effect size, and it is a method supplementary to Cohen’s d. It is used because, in many studies, the sample size for overall results is not large. In the interpretation of the effect size, a Hedges’ g of 0.2 or more and less than 0.5 denotes a small effect, 0.5 or more to less than 0.8 shows a medium effect, and 0.8 or more indicates a large effect.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Subject

A total of 893 children participated in the atopic forest camp, of which 612 participated in the 1-night and 2-day program, while 281 children participated in the 2-night and 3-day program. The ratio of males to females in children was similar, although there were slightly more males than females.

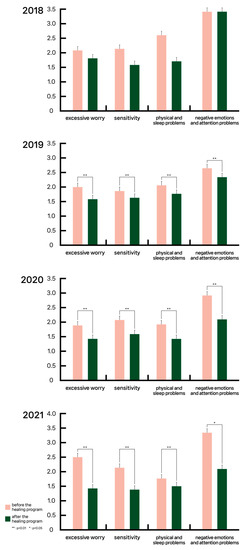

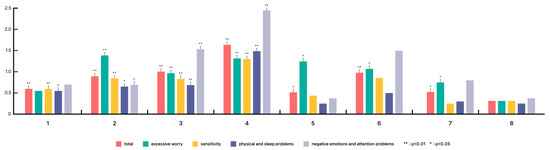

3.2. Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale: RCMASS

To evaluate the effect of the forest healing program on the psychological changes in patients with atopic dermatitis, RCMAS was measured before and after the healing program conducted from 2018 to 2021. Subsequently, the RCMAS was divided into subdomains each year to examine changes before and after the healing program (Figure 2 and Table 5). In 2018, none of the subdomains of the RCMAS were significant. However, in 2019, excessive worry, physical and sleep problems, negative emotions, attention problems (p < 0.001), and sensitivity (p = 0.001) were all significant. In 2020, excessive worry (p = 0.0003), sensitivity (p = 0.002), physical and sleep problems (p = 0.001), and negative emotions and attention problems (p < 0.001) were all significant. In 2021, excessive worry, sensitivity, and negative emotions and attention problems were all significant (p < 0.001), as were physical and sleep problems (p = 0.035). The subdomain of the RCMAS was reviewed from 2018 to 2021 when the forest healing program was conducted. The scores of excessive worry, physical and sleep problems, negative emotions, and attention problems were significantly different before and after the healing program.

Figure 2.

Results of RCMAS subdomains for each year 2018–2021.

Table 5.

Results of RCMAS subdomains for each year 2018–2021.

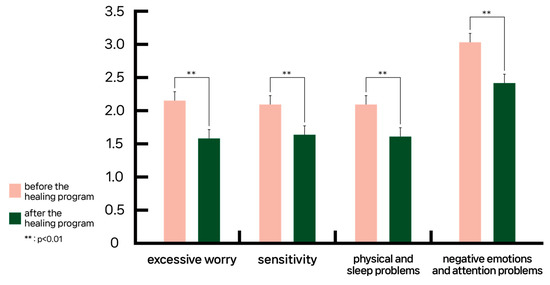

To determine the change in RCMAS before and after the atopic forest camp, we looked at the total before and after scores measured from 2018 to 2021 (Figure 3). The total score of the RCMAS represents the characteristic anxiety of the children, which was 8.99 points before the forest camp and decreased by 2.05 points to 6.94 after the camp, which was significant. Thus, the atopic forest camp is effective in reducing children’s anxiety.

Figure 3.

Results of subdomains for RCMAS during 2018–2021.

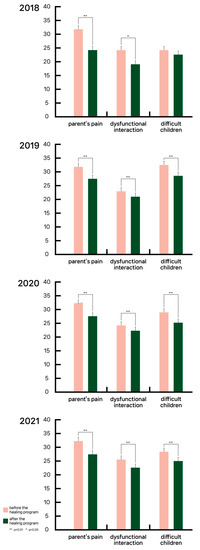

3.3. Korean Version of the Parenting Stress Index: K-PSI-SF

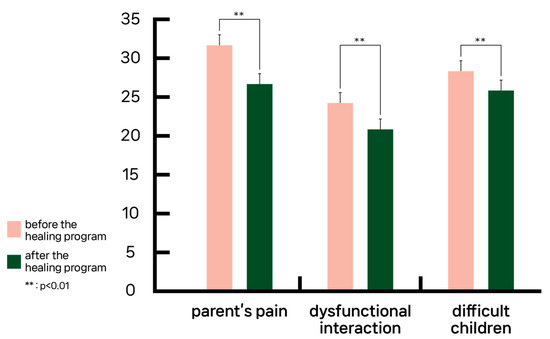

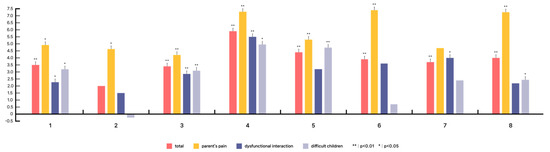

Subsequently, the K-PSI-SF was divided into subdomains for each year to examine the changes before and after the healing program (Figure 4 and Table 6). In 2018, parental pain (p = 0.007) and dysfunctional interaction (p = 0.024) were significantly found in the subdomain of the K-PSI-SF, although the difference was not significant for difficult children. In 2019, all subdomains of the K-PSI-SF were significant (p < 0.001). In 2020, parents’ pain and difficult children (p < 0.001), and dysfunctional interaction (p = 0.001) were significant. All 2021 subdomains were significant (p < 0.001). From 2018 to 2021, when the forest healing program was conducted, we examined the entire subdomain of the K-PSI-SF. The scores for parental pain, dysfunctional interaction, and difficult children were significantly different before and after the healing program.

Figure 4.

Results of K-PSI-SF subdomains for each year 2018–2021.

Table 6.

Results of K-PSI-SF subdomains for each year 2018–2021.

To determine the changes in the K-PSI-SF before and after the atopic forest camp, we looked at the total before and after scores measured from 2018 to 2021 (Figure 5). The total score of the K-PSI-SF represents parenting stress, which was 73.59 points before the forest camp, yet decreased by 8.63 points to 64.96 points after the camp, which was significant. Thus, the progress of the atopic forest camp was effective in reducing parenting stress.

Figure 5.

Results of subdomains for K-PSI-SF during 2018–2021.

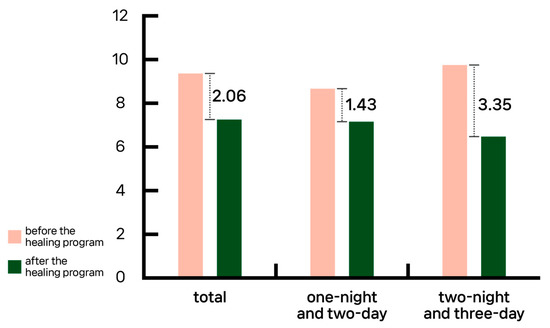

3.4. Comparison of the Effects between the One-Night and Two-Day Program and the Two-Night and Three-Day Program

The effects of the number of days in the forest healing program on the psychological changes to the children and caregivers and on the forest healing effects were examined. From 2018 to 2020, the program offered one-night and two-day programs; in 2021, two-night and three-day programs were provided. The total RCMAS score for the children who received the one-night and two-day program was 8.62 before the program and 7.19 after the program, showing a decrease of 1.43 (Figure 6 and Table 7). The RCMAS score in 2021, after the two-night and three-day program, decreased from 9.76 before the program to 6.41 after the program, showing a reduction of 3.35. Hence, the total score of the RCMAS decreased by 2.06, which is more than for the one-night and two-day program, and the two-night, three-day program was found to be more effective in reducing the children’s anxiety.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the effects between the one-night and two-day and two-night and three-day programs for RCMAS.

Table 7.

Comparison of the effects between the one-night and two-day and two-night and three-day programs for RCMAS.

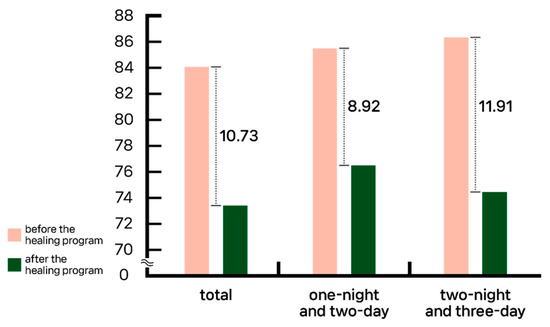

The total K-PSI-SF scores for the caregivers who received the one-night and two-day program were 85.47 before the program and 76.55 after the program, demonstrating a decrease of 8.92(Figure 7 and Table 8). As a result of implementing the program for two nights and three days, it decreased by 11.91, from 86.32 before the program to 74.41 after the program. When the two-night and three-day program was conducted, it was found that the total K-PSI-SF score decreased by 2.99 more than for the one-night and two-day program, proving that the two-night and three-day program reduced parenting stress more effectively.

Figure 7.

Comparison of the effects between the one-night and two-day and two-night and three-day programs for K-PSI-SF.

Table 8.

Comparison of the effects between the one-night and two-day and two-night and three-day programs for K-PSI-SF.

3.5. A Comparison of the Effects of Forest Healing Program on the Site

Forest healing programs were conducted in a total of eight recreational facilities for atopic children and caregivers who participated in the atopic forest camp. Each region’s forest healing programs were structured around the local characteristics of recreational facilities. This study looked into whether the institution had an impact on the effectiveness of forest healing (Figure 8 and Figure 9). The National Chilgok Forest Center and the National Forest Healing Center were both important locations to consider when evaluating the effectiveness of the detailed items of RCMA and K-PSI-SF, the measurement indicators carried out by children and caregivers by a target area. According to the forest type of the two areas, the National Chilgok Forest Garden consisted of other broad-leaved trees and other oak trees, and the National Forest Healing Center consisted of sedimentation mixed forests and pine trees. It was discovered through this that broadleaf trees are the predominant species. In addition, detailed forest healing programs conducted by each institution were different, yet the walking activities were common. The National Chilgok Forest Center was the site where patients’ and caregivers’ psychological scores changed the most after the forest healing program was offered. Daejeon National Forest Park was identified as the location with the least amount of psychological scale change, and Hoengseong National Forest Park for the caregiver.

Figure 8.

Effects of forest healing programs for children in each institution. Note: The x-axis represents the areas of soopchewon and forest healing centers located throughout the country. The y-axis is the value of the RCMA changed after the program progressed. (1: Chuncheon, 2: Hoengseong, 3: Forest Healing Center, 4: Chilgok, 5: Cheongdo, 6: Naju, 7: Jangseong, 8: Daejeon).

Figure 9.

Effects of forest healing programs for caregivers in each institution. Note: The x-axis represents the areas of soopchewon and forest healing centers located throughout the country. The y-axis is the value of the K-PSI-SF changed after the program progressed. (1: Chuncheon, 2: Hoengseong, 3: Forest Healing Center, 4: Chilgok, 5: Cheongdo, 6: Naju, 7: Jangseong, 8: Daejeon).

3.6. Hedges’ g Effect Size

3.6.1. Effect Size According to Subdomain

To evaluate the effect of the forest healing program on the psychological changes in patients with atopic dermatitis, RCMAS was measured before and after the healing program conducted from 2018 to 2021. Subsequently, the RCMAS was divided into subdomains for each year to examine the effect sizes before and after the healing program. In 2018, only physical and sleep problems showed a small effect size with Hedges’ g = 0.45, and in 2019, it was difficult to estimate the size of the effect. In 2020, small effects were shown in all (Hedges’ g = excessive worry: 0.25, sensitivity: 0.29, physical and sleep problems: 0.28, negative emotions and attention problems: 0.40), and in 2021, except for physical and sleep problems, all showed intermediate effect sizes (Hedges’ g = excessive worry: 0.58, sensitivity: 0.54, physical and sleep problems: 0.14, negative emotions and attention problems: 0.56).

Subsequently, the K-PSI-SF was divided into subdomains for each year to examine the effect sizes before and after the healing program. In 2018, except for difficult children, all subdomains showed intermediate effect sizes, and in 2019, all showed small effect sizes. Both, in 2020 (Hedges’ g = parent’s pain: 0.63, dysfunctional interaction: 0.27, difficult children: 0.39) and 2021 (Hedges’ g = parent’s pain: 0.57, dysfunctional interaction: 0.43, difficult children: 0.46), showed more than a small effect size.

3.6.2. Comparison of the Effects of One-Night and Two-Day Program and Two-Night and Three-Day Program

For children, the effect sizes of the one-night, two-day program and the two-night, three-day program were examined. For the one-night, two-day program, Hedges’ g = 0.23, showing a small effect size. For the two-night three-day program, Hedges’ g = 0.61, showing an intermediate effect size. Thus, when a forest healing program was provided to children, programs with a longer number of nights showed a greater forest healing effect.

For caregivers, the effect sizes of the forest healing effect of the one-night, two-day program and the two-night, three-day program were examined. For the one-night, two-day program, Hedges’ g = 0.23, showing a small effect size. For the two-night, three-day program, there was a larger effect size of 1.89. For the two-night, three-day program, Hedges’ g = 0.55, showing an intermediate effect size. Thus, when a forest healing program was provided to caregivers, the programs with the fewest days of stay showed a greater forest healing effect.

3.6.3. A Comparison of the Effects of Forest Healing Program on the Site

Forest healing programs were conducted in a total of eight recreational facilities for atopic children and caregivers who participated in the atopic forest camp. Each region’s forest healing programs were structured around the local characteristics of recreational facilities. This study looked into whether the institution had an impact on the effectiveness of forest healing (Table 9). The National Chilgok and Chuncheon Forest Center, and the National Forest Healing Center were both important locations to consider when evaluating the effect size of the detailed items of RCMA and K-PSI-SF, the measurement indicators carried out by children and caregivers by a target area.

Table 9.

A Comparison of the Effects of Forest Healing Program on the Site.

When the forest healing program was provided, the site with the largest forest healing effect size for children and caregivers was the National Chilgok Forest Park. The National Daejeon and Jangseong Forest Center were the places where the effect size of the children was insufficient, while Hoengseong was identified for the caregiver.

4. Discussion

According to previous studies, forest healing programs for atopic children exist, although for families, the purpose of knowledge transfer programs, such as education and management programs for atopic children, are limited. This study attempted to verify the effectiveness of an atopic forest camp, as a stress solution for not only atopic children but also caregivers. To evaluate the effect of the forest healing camp on the psychological changes in children and caregivers with atopic dermatitis, changes before and after the healing program, conducted from 2018 to 2021, were reviewed. As a result of looking at the subdomains, after measurements using RCMAS that can determine the characteristic anxiety of children and adolescents, none of them were significant in 2018. There was a significant improvement from 2019 to 2021. The total RCMA score was significantly improved through the forest camp program. As a result of looking at the subdomains using the K-PSI-SF, which can measure parenting stress, there were significant differences before and after parental pain and dysfunctional interactions in 2018. From 2019 to 2021, all subdomains improved significantly. The total score of the K-PSI-SF was also significantly improved through the forest camp. This was consistent with the results of previous studies showing that atopic forest camps are effective in reducing children’s anxiety.

When the children were provided with the two-night, three-day program, anxiety decreased more. Hedges’ g, which was calculated to determine the standardized forest healing effect size, also showed a larger effect size for the two-night, three-day program. Parenting stress also decreased more when the caregivers were provided with a two-night, three-day forest healing program. However, Hedges’ g showed a larger effect size when the one-night, two-day program was provided. The psychological stress of patients and caregivers decreased more effectively when they were provided with the program for two nights and three days than the one-night and two-day program, which is consistent with the results of previous studies, which showed that the longer the time spent in the forest, the greater the effect of forest healing [43].

There are forest healing programs for atopic children in each institution. However, since each institution has a different forest environment and operates a forest healing program that is organized according to the characteristics of the region, it is expected that the effect size of forest healing will be different. Phytoncide, landscape, sound, anion, and light topography exist as physical environmental factors that affect forest healing. In addition, factors caused by forest activities, such as providing opportunities for introspection, meditation, conversation, and counseling as psychological and social factors, become factors in forest healing [44]. As a result of operating forest healing programs in eight institutions with different forest healing factors, the places where the detailed items of both the RCMA of the patient and the K-PSI-SF questionnaire of the caregiver were found to be the National Chilgok Forest Center and the National Forest Healing Center. Broadleaf trees were the predominant species in the forest environments that proliferated significantly. In addition, walking activities existed as a common program. According to previous studies, it has been reported that activity in forests can be a means of physiological and psychological treatment due to reduced stress and increased alpha waves [45]. In particular, phytoncide is said to relieve inflammation and stimulate human smell, resulting in the stability and comfort of the mind [29]. Comparing phytoncide emitted from coniferous forests and broad-leaved forests, it was found that the alpha wave generation of parietal and laryngeal leaves was high in broad-leaved forests. It was found that coniferous forests can cause a gloomy atmosphere and tension, while broad-leaved forests can increase comfort and preference [46,47]. In such previous studies, the forest healing effect was more significant because the forest type of the National Chilgok Forest Center and the National Forest Healing Center, which showed significant questionnaire items for atopic children and caregivers, had broad-leaved tree species in common. Another thing in common between the National Chilgok Forest Gymnasium and the National Forest Healing Center was that there were walking activities. According to previous studies, walking in the forest is more helpful in reducing stress by improving emotions and mood than exercising in an artificial environment [48]. Moreover, it is said that walking activities had a positive effect of more than 60.0%, both psychologically and physically [49]. Through this, the predominant tree species among the forest healing programs conducted by eight institutions are broad-leaved tree species, and the forest healing effect of the National Chilgok Forest Center and the National Forest Healing Center, which conducted programs that included walking activities, seems to be more significant.

However, in this study, it was not clear what kind of activity produced the forest healing effect because the forest healing programs provided by the Healing Center and SoopCheWon were different. It is unfortunate that various effects cannot be known because only one psychological scale was used for atopic children and caregivers. In addition to forest type and detailed activities, there are various factors that determine the effect of forest healing when conducting forest healing programs. In addition to forest type and detailed activities, there are various factors that determine the effect of forest healing when conducting forest healing programs.

However, it is important that not only children with atopic dermatitis but also their families were selected as subjects, and the fact that the study was conducted for an extended period sets it apart from other studies. It was confirmed that forest camps proved to have a positive effect on the psychological stability of a large number of atopic children and their families. This is meaningful as basic data for forest healing programs for children with atopic dermatitis and their families. In the future, if research is conducted on atopic children and families by supplementing the psychological scale, it will be possible to verify the effectiveness of the forest healing program.

5. Conclusions

According to previous studies, forest healing programs for atopic children exist, although for their families, the purpose of knowledge transfer programs, such as education and management programs for atopic children, are limited. In this study, we attempted to verify the effectiveness of providing atopic forest camps, as a psychological stabilization plan for children with atopic dermatitis and their caregivers. The study results showed that the anxiety of atopic children and the stress of their caregivers decreased through the provision of forest camps. Results of the study show that the total RCMA and K-PSI-SF scores were significantly improved after the forest camp compared to before. In addition, the total RCMA and K-PSI-SF scores decreased more when the forest healing program was conducted for two nights and three days compared to the one-night and two-day program. However, Hedges’ g, which was calculated to determine the standardized forest healing effect size, showed a larger forest healing effect size in children for the longer program, while a larger effect size was shown for the caregivers with the shorter program. In addition, there are many forest healing programs conducted for the same subject, yet they were aware that the forest healing effects were different depending on the forest environment and detailed programs. Through this study, the effectiveness of the forest healing program conducted by each institution for atopic children was reviewed. As a result, as a characteristic of institutions with significant improvement in all items, broadleaf tree species exist in the forest type, and walking activities were included in detailed activities.

In addition, broad-leaved tree species are distributed as major trees, and it can be seen that forest healing programs, including walking activities, have significantly improved their psychological aspects.

The results of this study intend to provide an opportunity to construct a forest healing program, not only for children with atopic dermatitis but also for their caregivers. Through the results of this study, we intend to provide an opportunity for children, who are atopic patients, to receive forest healing programs and even for caregivers in the future. Based on this, the authors hope that a system for a forest healing program will be established that can provide care for atopic children and their families.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K., S.P. and G.K.; methodology, Y.C.; software, G.K. validation, S.K. and Y.C.; formal analysis, S.K.; investigation, Y.C.; resources, S.P. and G.K.; data curation, S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.P. and G.K.; visualization, Y.C.; supervision, S.P.; project administration, G.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available since they are collected for internal research purposes of the National Institute of Forest Science, Republic of Korea.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out with the support of the ‘R&D Program for Forest Science Technology (Project No. 2021388B10-2323-0102)’ provided by the Korea Forest Service (Korea Forestry Promotion Institute).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Draelos, Z.D.; Feldman, S.R.; Berman, B.; Olivadoti, M.; Sierka, D.; Tallman, A.M.; Zielinski, M.A.; Ports, W.C.; Baldwin, S. Tolerability of Topical Treatments for Atopic Dermatitis. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 9, 71–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichenfield, L.F.; Tom, W.L.; Chamlin, S.L.; Feldman, S.R.; Hanifin, J.M.; Simpson, E.L.; Berger, T.G.; Bergman, J.N.; Cohen, D.E.; Cooper, K.D. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 70, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, J.; Gawkrodger, D.J.; Mortimer, M.J.; Jaron, A.G. The prevalence of childhood atopic eczema in a general population. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994, 30, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojnarowska, F.; Eady, R.; Burge, S.; Champion, R.; Burton, J.; Burns, D.; Breathnach, S. Dermatitis herpetiformis. In Textbook of Dermatology; Champion, R.H., Burton, J.L., Burns, D.A., Breathnach, S.M., Eds.; Blackwell Science: Oxford, UK, 1998; Volume 3, pp. 1888–1892. [Google Scholar]

- Schmied, C.; Saurat, J.-H. Epidemiology of atopic eczema. In Handbook of Atopic Eczema; Ruzicka, T., Ring, J., Przybilla, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; pp. 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, F.S.; Diepgen, T.; Svensson, Å. The occurrence of atopic dermatitis in North Europe: An international questionnaire study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1996, 34, 760–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, R.J.; Johns, N.E.; Williams, H.C.; Bolliger, I.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Margolis, D.J.; Marks, R.; Naldi, L.; Weinstock, M.A.; Wulf, S.K.; et al. The Global Burden of Skin Disease in 2010: An Analysis of the Prevalence and Impact of Skin Conditions. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2014, 134, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuveni, H.; Chapnick, G.; Tal, A.; Tarasiuk, A. Sleep fragmentation in children with atopic dermatitis. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1999, 153, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnet, J.; Jemec, G. An assessment of anxiety and dermatology life quality in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 1999, 140, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S.; Ryan, T. Skin disease and handicap: An analysis of the impact of skin conditions. Soc. Sci. Med. 1985, 20, 425–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.C.; Funnell, C.; Collard, R.; Finlay, A. What do members of the National Eczema Society really want? Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1993, 18, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurwa, H.; Finlay, A.Y. Dermatology in-patient management greatly improves life quality. Br. J. Dermatol. 1995, 133, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, H.C.; Finlay, A. Measurement of Atopic Dermatitis Disability. Ann. Dermatol. 1990, 2, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salek, M.; Finlay, A.Y.; Luscombe, D.K.; Allen, B.; Berth-Jones, J.; Camp, R.; Graham-Brown, R.; Khan, G.; Marks, R.; Motleyj, R. Cyclosporin greatly improves the quality of life of adults with severe atopic dermatitis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Br. J. Dermatol. 1993, 129, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guyatt, G.H.; Feeny, D.H.; Patrick, D.L. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993, 118, 622–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.T.; Rajagopalan, R. Development and validation of a quality of life instrument for cutaneous diseases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1997, 37, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, H.C. A 10-year-old girl with atopic dermatitis reports itching that has recently become relentless, resulting in sleep loss. Her mother has been reluctant to treat the girl with topical corticosteroids, because she was told that they damage the skin, but she is exhausted and wants relief for her child. How should the problem be managed? N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 2314–2324. [Google Scholar]

- Chamlin, S.L.; Mattson, C.L.; Frieden, I.J.; Williams, M.L.; Mancini, A.J.; Cella, D.; Chren, M.-M. The price of pruritus: Sleep disturbance and cosleeping in atopic dermatitis. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2005, 159, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, L.R.; Garralda, M.E.; David, T.J. Psychosocial adjustment in preschool children with atopic eczema. Arch. Dis. Child. 1993, 69, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghmaie, P.; Koudelka, C.W.; Simpson, E.L. Mental health comorbidity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 131, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradisi, M.; Pedicelli, C.; Paradisi, A.; El Hachem, M.; Rota, C.; Burroni, A.G.; Andreoli, E. Dermatitis due to self-aggressive behaviors in pediatric age. Eur. J. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2013, 23, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Jones, M.S.; Finlay, A.Y.; Dykes, P.J. The infants’ dermatitis quality of life index. Br. J. Dermatol. 2001, 144, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.C.; Kemp, A.S.; Varigos, G.A.; Nolan, T.M. Atopic eczema: Its impact on the family and financial cost. Arch. Dis. Child. 1997, 76, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, J.M.; Whitlock, F.A. Emotions and the Skin: The Conditioning of Scratch Responses in Cases of Atopic Dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 1972, 86, 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginsburg, I.H.; Prystowsky, J.H.; Kornfeld, D.S.; Wolland, H. Role of Emotional Factors in Adults with Atopic Dermatitis. Int. J. Dermatol. 1993, 32, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashiro, M.; Okumura, M. Anxiety, depression and psychosomatic symptoms in patients with atopic dermatitis: Comparison with normal controls and among groups of different degrees of severity. J. Dermatol. Sci. 1997, 14, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.M.; Wilson, G.V. Use of a diary technique to investigate psychosomatic relations in atopic dermatitis. J. Psychosom. Res. 1991, 35, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrie, E.V.; Garrie, S.A.; Mote, T. Anxiety and atopic dermatitis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1974, 42, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KFS (Korea Forest Service). 2023. Available online: https://www.forest.go.kr (accessed on 15 January 2023). (In Korean)

- Park, B.-J.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Kasetani, T.; Hirano, H.; Kagawa, T.; Sato, M.; Miyazaki, Y. Physiological effects of shinrin-yoku (taking in the atmosphere of theforest)—Using salivary cortisol and cerebral activity as indicators. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2007, 26, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag-Öström, E.; Stenlund, T.; Nordin, M.; Lundell, Y.; Ahlgren, C.; Fjellman-Wiklund, A.; Järvholm, L.S.; Dolling, A. “Nature’s effect on my mind”—Patients’ qualitative experiences of a forest-based rehabilitation programme. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, G.X.; Lan, X.G.; Cao, Y.B.; Chen, Z.M.; He, Z.H.; Lv, Y.D.; Wang, Y.Z.; Hu, X.L.; Wang, G.F.; Yan, J. Effects of short-term forest bathing on human health in a broad-leaved evergreen forest in Zhejiang Province, China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2012, 25, 317–324. [Google Scholar]

- Berman, M.G.; Jonides, J.; Kaplan, S. The Cognitive Benefits of Interacting with Nature. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 19, 1207–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peen, J.; Schoevers, R.A.; Beekman, A.T.; Dekker, J. The current status of urban-rural differences in psychiatric disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2010, 121, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Den Berg, A.E.; Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.S.; Shin, C.S.; Yeoun, P.S.; Kim, J.J. The influence of interaction with forest on cognitive function. Scand. J. For. Res. 2011, 26, 595–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, E.; Fukuda, S.; Nagano, J.; Hamajima, N.; Yamamoto, H.; Iwai, Y.; Nakashima, T.; Ohira, H.; Shirakawa, T. Psychological effects of forest environments on healthy adults: Shinrin-yoku (forest-air bathing, walking) as a possible method of stress reduction. Public Health 2007, 121, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, W.S.; Shin, C.S.; Yeoun, P.S. The influence of forest therapy camp on depression in alcoholics. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2011, 17, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.-D.; Koo, C.-D. A Study of Walking, Viewing and Fragrance-based Forest Therapy Programs Effect on Living Alone Adults’ Dementia Prevention. Korean J. Environ. Ecol. 2019, 33, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Bang, K.; Kim, S.; Choi, H.; Lee, B.; Song, M. Effect of Forest Program on Atopic Dermatitis in Children—A Systematic Review. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2016, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Lee, S.M.; Seo, S.C.; Choung, J.T.; Lee, S.J.; Park, S.J.; Park, C.W. The clinical and immunological effects of forest camp on childhood environmental diseases. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2011, 15, 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, W.S.; Kim, S.K.; Yeon, P.S.; Lee, J.H. Effects of Phytoncides on Psychophysical Responses. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2010, 14, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Kim, D.; Lee, K.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y. A study on effect of forest related programs based on the meta-analysis. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2015, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, R. Study on the Practical Use of the Forest Therapeutic Effect. J. For. Sci. 2007, 70, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, W.; Yeoun, P.; Lee, J. The impact that a forest experience influences on a human mental state stability. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2007, 11, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.I.; Hwang, S.H.; Shin, W.S.; An, K.W. Physiological effect of forest types: Focused on brain wave and pulsation. J. Kor. Inst. Forest Recreat. 2002, 6, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.; Song, T.; An, K.; Tada, M. Forest spatial image evaluation for recreation management. J. Rural Tour. 2002, 9, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S. A study on recovery of wellness healing forest. J. Korean Inst. Cult. Prod. Des. 2015, 41, 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, G.; Choi, Y.; Kim, E.; Paek, D. Evidence-based status of forest healing program in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).