Experimental Precipitation Reduction Slows Down Litter Decomposition but Exhibits Weak to No Effect on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks in Three Mediterranean Forests of Southern France

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Litter Decomposition Experiment

2.3. Soil Sampling and Carbon and Nitrogen Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

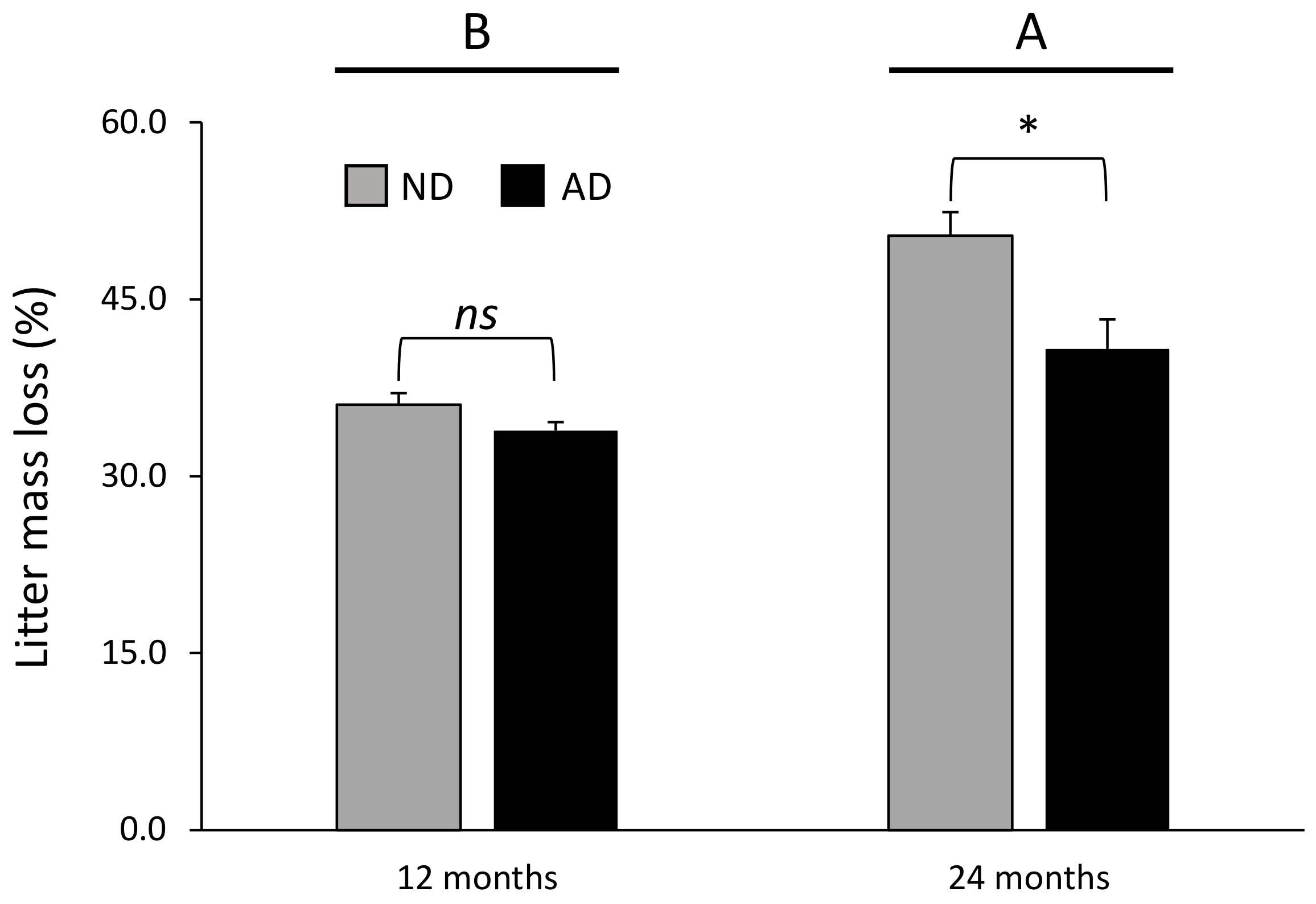

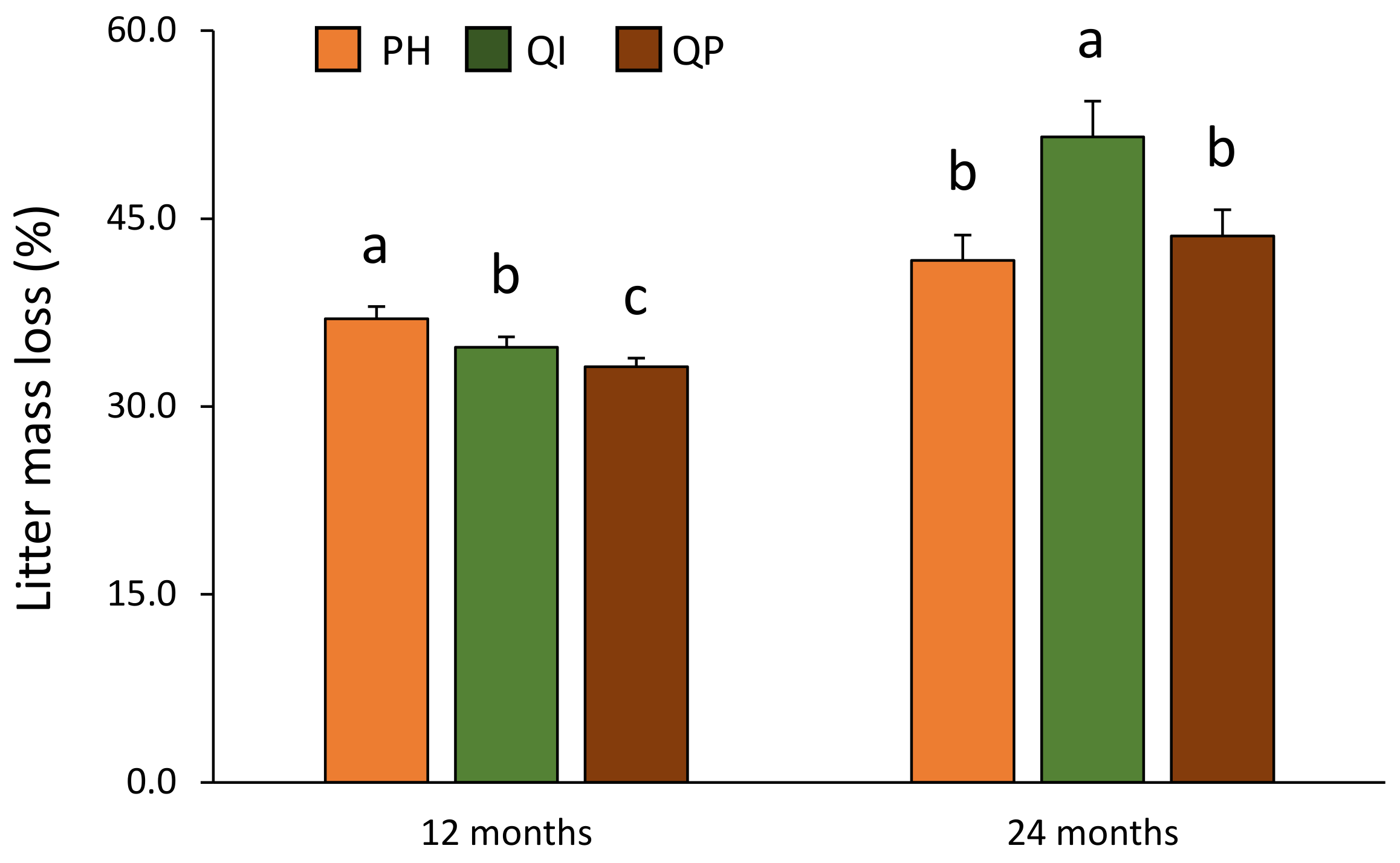

3.1. Litter Mass Loss during the Decomposition Process

3.2. SOC and SN Concentrations

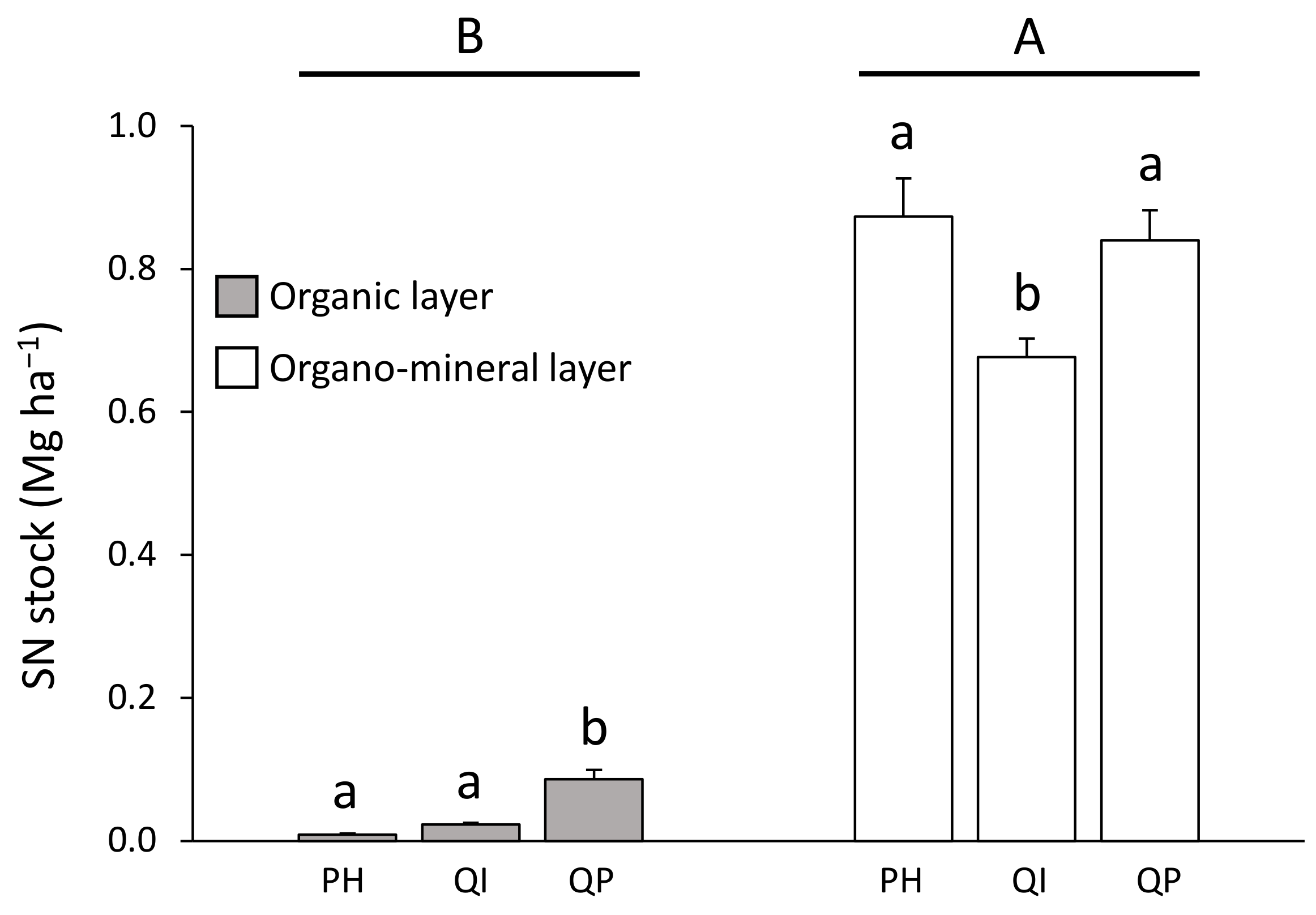

3.3. SOC and SN Stocks

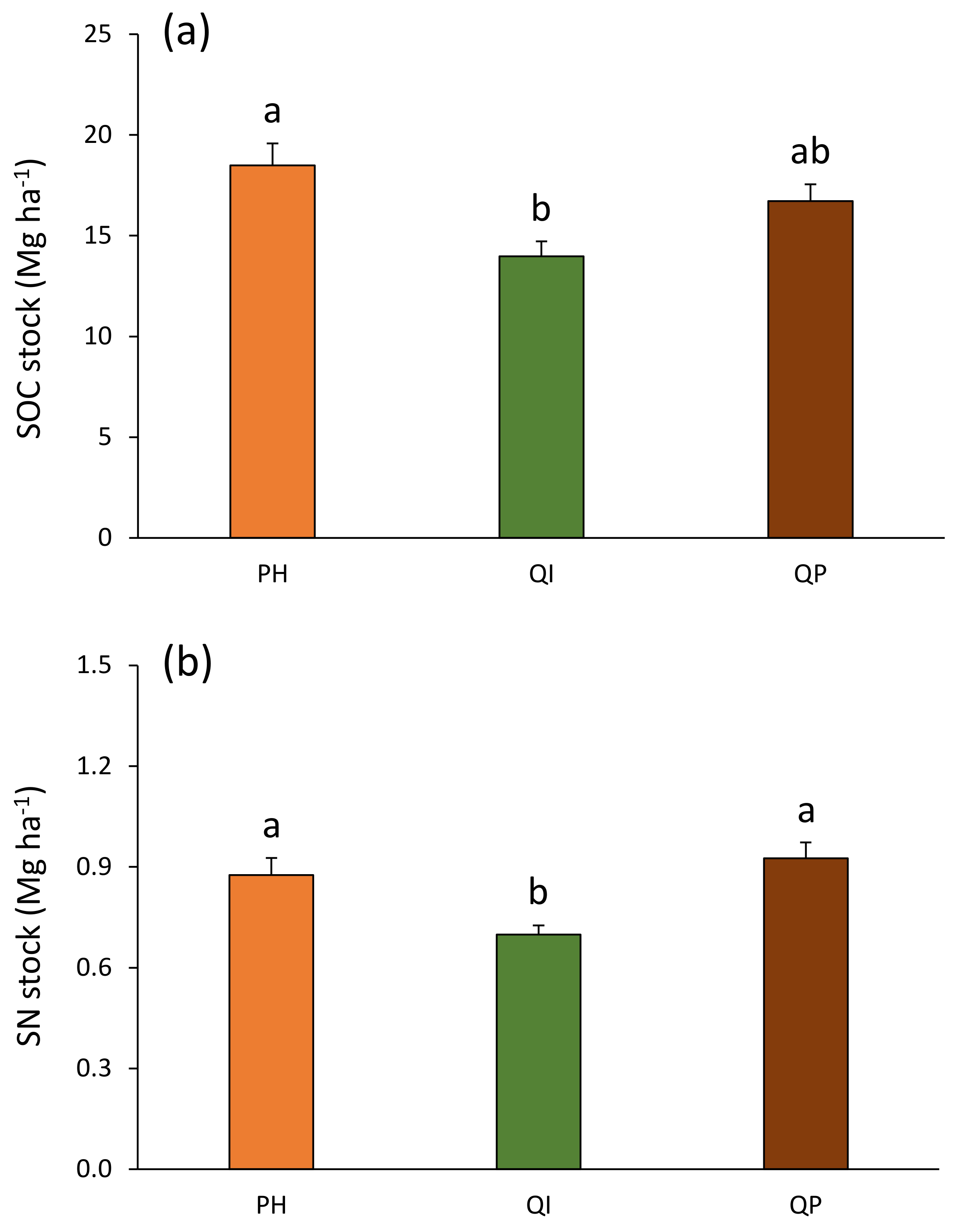

3.4. Total SOC and SN Stocks in the First 10 cm Soil Depth

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Hauck, J.; Olsen, A.; Peters, G.P.; Peters, W.; Pongratz, J.; Sitch, S.; et al. Global carbon budget 2020. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 3269–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luo, Y.; Yu, G.; Zhang, L. Estimated carbon residence times in three forest ecosystems of eastern China: Applications of probabilistic inversion. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2010, 115, G1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, A.A.; Exbrayat, J.F.; Van Der Velde, I.R.; Feng, L.; Williams, M. The decadal state of the terrestrial carbon cycle: Global retrievals of terrestrial carbon allocation, pools, and residence times. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1285–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. Geoderma 2004, 123, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Forest soils and carbon sequestration. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 220, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A.; Schneider, F. Roots are key to increasing the mean residence time of organic carbon entering temperate agricultural soils. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2021, 27, 4921–4934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A large and persistent carbon sink in the world’s forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, R.J.; Reams, G.A.; Achard, F.; de Freitas, J.V.; Grainger, A.; Lindquist, E. Dynamics of global forest area: Results from the FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2015. For. Ecol. Manag. 2015, 352, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Quéré, C.; Andrew, R.M.; Friedlingstein, P.; Sitch, S.; Hauck, J.; Pongratz, J.; Pickers, P.A.; Korsbakken, J.I.; Peters, G.P.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. Global carbon budget 2018. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2018, 10, 2141–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthelin, J.; Laba, M.; Lemaire, G.; Powlson, D.; Tessier, D.; Wander, M.; Baveye, P.C. Soil carbon sequestration for climate change mitigation: Mineralization kinetics of organic inputs as an overlooked limitation. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, B.; Cools, N.; Ilvesniemi, H.; Vesterdal, L.; Vanguelova, E.; Carnicelli, S. Benchmark values for forest soil carbon stocks in Europe: Results from a large scale forest soil survey. Geoderma 2015, 251–252, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Eisenhauer, N.; Sierra, C.A.; Bessler, H.; Engels, C.; Griffiths, R.; Mellado-Vázquez, P.G.; Malik, A.A.; Roy, J.; Scheu, S.; et al. Plant diversity increases soil microbial activity and soil carbon storage. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausch, J.; Kuzyakov, Y. Carbon input by roots into the soil: Quantification of rhizodeposition from root to ecosystem scale. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2018, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, W.; Yang, S.; Yang, L.; Peng, Z.; Deng, M.; Xu, S.; Zhang, B.; Ahirwal, J.; Liu, L. Plant carbon inputs through shoot, root, and mycorrhizal pathways affect soil organic carbon turnover differently. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 160, 108322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, L.; Feng, X.; Zhang, J.; Ma, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z. Comparing soil carbon loss through respiration and leaching under extreme precipitation events in arid and semiarid grasslands. Biogeosciences 2018, 15, 1627–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobbágy, E.G.; Jackson, R.B. The vertical distribution of soil organic carbon and its relation to climate and vegetation. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Dang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, X. Soil carbon dynamics following land-use change varied with temperature and precipitation gradients: Evidence from stable isotopes. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015, 21, 2762–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.P.; Wattenbach, M.; Smith, P.; Meersmans, J.; Jolivet, C.; Boulonne, L.; Arrouays, D. Spatial distribution of soil organic carbon stocks in France. Biogeosciences 2011, 8, 1053–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meersmans, J.; Martin, M.P.; Lacarce, E.; De Baets, S.; Jolivet, C.; Boulonne, L.; Lehmann, S.; Saby, N.; Bispo, A.; Arrouays, D. A high resolution map of French soil organic carbon. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbow, H.O.P.; Reisinger, A.; Canadell, J.; O’Brien, P. Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems (SR2); IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 650. [Google Scholar]

- Pörtner, H.O.; Roberts, D.C.; Adams, H.; Adler, C.; Aldunce, P.; Ali, E.; Fischlin, A. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Liski, J.; Karjalainen, T.; Pussinen, A.; Nabuurs, G.J.; Kauppi, P. Trees as carbon sinks and sources in the European Union. Environ. Sci. Policy 2000, 3, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liski, J.; Perruchoud, D.; Karjalainen, T. Increasing carbon stocks in the forest soils of western Europe. For. Ecol. Manag. 2002, 169, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonan, G.B. Forests and climate change: Forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 2008, 320, 1444–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, D., Jr.; Houghton, R.A. Gross CO2 fluxes from land-use change: Implications for reducing global emissions and increasing sinks. Carbon Manag. 2011, 2, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Médail, F.; Quézel, P. Biodiversity hotspots in the Mediterranean Basin: Setting global conservation priorities. Conserv. Biol. 1999, 13, 1510–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauquelin, T.; Michon, G.; Joffre, R.; Duponnois, R.; Génin, D.; Fady, B.; Dagher-Kharrat, M.B.; Derridj, A.; Slimani, S.; Badri, W.; et al. Mediterranean forests, land use and climate change: A social-ecological perspective. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 18, 623–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croitoru, L. How much are Mediterranean forests worth? For. Policy Econ. 2007, 9, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Plant-soil interactions in Mediterranean forest and shrublands: Impacts of climatic change. Plant Soil 2013, 365, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratani, L.; Varone, L.; Ricotta, C.; Catoni, R. Mediterranean shrublands carbon sequestration: Environmental and economic benefits. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2013, 18, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Peinado, R.; Oviedo, J.A.B.; Senespleda, E.L.; Oviedo, F.B.; del Río Gaztelurrutia, M. Forest management and carbon sequestration in the Mediterranean region: A review. For. Syst. 2017, 26, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Guardia, S.; Peri, P.L.; Amelung, W.; Sheil, D.; Laffan, S.W.; Borchard, N.; Bird, M.I.; Dieleman, W.; Pepper, D.A.; Zutta, B.; et al. Better estimates of soil carbon from geographical data: A revised global approach. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2019, 24, 355–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M’Hirit, O. Mediterranean forests: Ecological space and economic and community wealth. Unasylva 1999, 50, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter, D.; Cramer, W.; Leemans, R.; Prentice, I.C.; Araújo, M.B.; Arnell, N.W.; Bondeau, A.; Bugmann, H.; Carter, T.R.; Gracia, C.A.; et al. Ecosystem service supply and vulnerability to global change in Europe. Science 2005, 310, 1333–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F.; Lionello, P. Climate change projections for the Mediterranean region. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2008, 63, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polade, S.D.; Pierce, D.W.; Cayan, D.R.; Gershunov, A.; Dettinger, M.D. The key role of dry days in changing regional climate and precipitation regimes. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuel, A.; Eltahir, E.A. Why is the Mediterranean a climate change hot spot? J. Clim. 2020, 33, 5829–5843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiafouli, M.A.; Kallimanis, A.S.; Katana, E.; Stamou, G.P.; Sgardelis, S.P. Responses of soil microarthropods to experimental short-term manipulations of soil moisture. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2005, 29, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Palacios, P.; Maestre, F.T.; Kattge, J.; Wall, D.H. Climate and litter quality differently modulate the effects of soil fauna on litter decomposition across biomes. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonja, M.; Fernandez, C.; Proffit, M.; Gers, C.; Gauquelin, T.; Reiter, I.M.; Cramer, W.; Baldy, V. Plant litter mixture partly mitigates the negative effects of extended drought on soil biota and litter decomposition in a Mediterranean oak forest. J. Ecol. 2017, 105, 801–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evolution of the French forest surface area since 1985. Available online: https://inventaire-forestier.ign.fr/spip.php?article875 (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- IGN. Résultats D’inventaire Forestier: Les Résultats des Campagnes D’inventaire 2009 à 2013 en Méditerranée. 2013. Available online: https://inventaire-forestier.ign.fr/IMG/pdf/RES-GRECO-2013/RS_0913_GRECO_J.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Moron-Rios, A.; Rodriguez, M.A.; Perez-Camacho, L.; Rebollo, S. Effects of seasonal grazing and precipitation regime on the soil macroinvertebrates of a Mediterranean old-field. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2010, 46, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardol, P.; Reynolds, W.N.; Norby, R.J.; Classen, A.T. Climate change effects on soil microarthropod abundance and community structure. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2011, 47, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupic-Samain, A.; Baldy, V.; Delcourt, N.; Krogh, P.H.; Gauquelin, T.; Fernandez, C.; Santonja, M. Water availability rather than temperature control soil fauna community structure and prey-predator interactions. Funct. Ecol. 2021, 35, 1550–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, M.J.; Heal, O.W.; Anderson, J.M. Decomposition in Terrestrial Ecosystems; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2006; World Soil Resources Reports; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006; No. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J. Comparisons of three methods for organic and inorganic carbon in calcareous soils of northwestern China. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonja, M.; Baldy, V.; Fernandez, C.; Balesdent, J.; Gauquelin, T. Potential shift in plant communities with climate change: Outcome on litter decomposition and nutrient release in a Mediterranean oak forest. Ecosystems 2015, 18, 1253–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonja, M.; Fernandez, C.; Gauquelin, T.; Baldy, V. Climate change effects on litter decomposition: Intensive drought leads to a strong decrease of litter mixture interactions. Plant Soil 2015, 393, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupic-Samain, A.; Baldy, V.; Lecareux, C.; Fernandez, C.; Santonja, M. Tree litter identity and predator density control prey and predator demographic parameters in a Mediterranean litter-based multi-trophic system. Pedobiologia 2019, 73, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, S.; Burešová, A.; Kopecky, J.; Mádrová, P.; Aupic-Samain, A.; Fernandez, C.; Baldy, V.; Sagova-Mareckova, M. Litter traits and rainfall reduction alter microbial litter decomposers: The evidence from three Mediterranean forests. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2019, 95, fiz168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hättenschwiler, S.; Coq, S.; Barantal, S.; Handa, I.T. Leaf traits and decomposition in tropical rainforests: Revisiting some commonly held views and towards a new hypothesis. New Phytol. 2011, 189, 950–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkonen, M.; Berg, M.P.; van Logtestijn, R.S.P.; van Hal, J.R.; Aerts, R. Do physical plant litter traits explain non-additivity in litter mixtures? A test of the improved microenvironmental conditions theory. Oikos 2013, 122, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Palacios, P.; McKie, B.G.; Handa, I.T.; Frainer, A.; Hättenschwiler, S. The importance of litter traits and decomposers for litter decomposition: A comparison of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems within and across biomes. Funct. Ecol. 2016, 30, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonja, M.; Pellan, L.; Piscart, C. Macroinvertebrate identity mediates the effects of litter quality and microbial conditioning on leaf litter recycling in temperate streams. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 2542–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martin, A.; Gallardo, J.F.; Santa Regina, I. Long-term decomposition process of leaf litter from Quercus pyrenaica forests across a rainfall gradient (Spanish central system). Ann. For. Sci. 1997, 54, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saura-Mas, S.; Estiarte, M.; Peñuelas, J.; Lloret, F. Effects of climate change on leaf litter decomposition across post-fire plant regenerative groups. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 77, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro, M.; Maestre, F.T.; Martínez-López, J.; Valencia, E.; Rey, A. Climate change may reduce litter decomposition while enhancing the contribution of photodegradation in dry perennial Mediterranean grasslands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2015, 90, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hättenschwiler, S.; Tiunov, A.V.; Scheu, S. Biodiversity and litter decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2005, 36, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessner, M.O.; Swan, C.M.; Dang, C.K.; McKie, B.G.; Bardgett, R.D.; Wall, D.H.; Hättenschwiler, S. Diversity meets decomposition. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2010, 25, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel Yuste, J.C.; Peñuelas, J.; Estiarte, M.; Garcia-Mas, J.; Mattana, S.; Ogaya, R.; Pujol, M.; Sardans, J. Drought-resistant fungi control soil organic matter decomposition and its response to temperature. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Drought decreases soil enzyme activity in a Mediterranean holm oak forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 37, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueso, S.; Hernandez, T.; Garcia, C. Resistance and resilence of the soil microbial biomass to severe drought in semiarid soils: The importance of organic amendments. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2011, 50, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupic-Samain, A.; Santonja, M.; Chomel, M.; Pereira, S.; Quer, E.; Lecareux, C.; Limousin, J.M.; Ourcival, J.M.; Simioni, G.; Gauquelin, T.; et al. Soil biota response to experimental rainfall reduction depends on the dominant tree species in mature Northern Mediterranean forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 154, 108122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkonen, M.; Berg, M.P.; Handa, I.T.; Hättenschwiler, S.; van Ruijven, J.; van Bodegom, P.M.; Aerts, R. Highly consistent effects of plant litter identity and functional traits on decomposition across a gradient. Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 1033–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djukic, I.; Kepfer-Rojas, S.; Schmidt, I.K.; Larsen, K.S.; Beier, C.; Berg, B.; Verheyen, K.; Caliman, A.; Paquette, A.; Gutiérrez-Girón, A.; et al. Early stage litter decomposition across biomes. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 628, 1369–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Butenschoen, O.; Barantal, S.; Handa, I.T.; Makkonen, M.; Vos, V.; Aerts, R.; Berg, M.P.; McKie, B.; Van Ruijven, J.; et al. Decomposition of leaf litter mixtures across biomes: The role of litter identity, diversity and soil fauna. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 2283–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baritz, R.; Seufert, G.; Montanarella, L.; Van Ranst, E. Carbon concentrations and stocks in forest soils of Europe. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 260, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomel, M.; Fernandez, C.; Bousquet-Mélou, A.; Gers, C.; Monnier, Y.; Santonja, M.; Gauquelin, T.; Gros, R.; Lecareux, C.; Baldy, V. Secondary metabolites of Pinus halepensis alter decomposer organisms and litter decomposition during afforestation of abandoned agricultural zones. J. Ecol. 2014, 102, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Rojas, M.; Jordán, A.; Martínez Zavala, L.; Rosa, D.D.L.; Abd-Elmabod, S.K.; Anaya Romero, M. Organic carbon stocks in Mediterranean soil types under different land uses (Southern Spain). Solid Earth 2012, 3, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oubrahim, H.; Boulmane, M.; Bakker, M.R.; Augusto, L.; Halim, M. Carbon storage in degraded cork oak (Quercus suber) forests on flat lowlands in Morocco. Iforest-Biogeosci. For. 2015, 9, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahim, N.; Ibrahim, H.; Hatira, A. Tunisian Soil Organic Carbon Stock-Spatial and Vertical Variation. Procedia Eng. 2014, 69, 1549–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Peinado, R.; Bravo-Oviedo, A.; López-Senespleda, E.; Montero, G.; Río, M. Do thinnings influence biomass and soil carbon stocks in Mediterranean maritime pinewoods? Eur. J. For. Res. 2013, 132, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parras-Alcántara, L.; Lozano-García, B.; Brevik, E.C.; Cerdá, A. Soil organic carbon stocks assessment in Mediterranean natural areas: A comparison of entire soil profiles and soil control sections. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 155, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sferlazza, S.; Maetzke, F.G.; Iovino, M.; Baiamonte, G.; Palmeri, V.; La Mela Veca, D.S. Effects of traditional forest management on carbon storage in a Mediterranean holm oak (Quercus ilex L.) coppice. Iforest-Biogeosci. For. 2018, 11, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dupouey, J.; Pignard, G.; Badeau, V.; Thimonier, A.; Dhôte, J.; Nepveu, G.; Bergès, L.; Augusto, L.; Belkacem, S.; Nys, C. Stocks et flux de carbone dans les forêts françaises. Comptes Rendus L’académie D’agriculture Fr. 1999, 85, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrouays, D.; Deslais, W.; Badeau, V. The carbon content of topsoil and its geographical distribution in France. Soil Use Manag. 2001, 17, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet, P.; Meredieu, C.; Seynave, I.; Belouard, T.; Dhôte, J.F. Species substitution for carbon storage: Sessile oak versus Corsican pine in France as a case study. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Sánchez, A.; Vanwalleghem, T.; Peña, A.; Laguna, A.; Giráldez, J.V. Controls on soil carbon storage from topography and vegetation in a rocky, semi-arid landscapes. Geoderma 2018, 311, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, C.; Vos, C.; Don, A. Soil organic carbon stocks are systematically overestimated by misuse of the parameters bulk density and rock fragment content. Soil 2017, 3, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Forests | Pinus halepensis | Quercus ilex | Quercus pubescens |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sites | Font-Blanche (FB) | Puéchabon (PC) | Oak Observatory at Observatoire de Haute Provence (O3HP) |

| Location | 43°14′27″ N, 5°40′45″ E | 43°44′29″ N, 3°35′46″ E | 43°56′16″ N, 5°42′64″ E |

| Altitude a.s.l. (m) | 425 | 270 | 650 |

| MAT (°C) | 13.7 | 14.0 | 12.6 |

| MAP ND (mm) | 605.0 | 955.4 | 866.3 |

| MAP AD (mm) | 441.6 | 698.9 | 639.5 |

| Soil type | Leptosol | Rhodo-chromic luvisol | Pierric calcosol |

| Soil texture | Clay | Clay loam | Clay |

| Soil pH | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.8 |

| Surface rock cover (%) | 50 | 75 | 23 |

| Dominant tree species | Mixed Pinus halepensis Mill./Quercus ilex L. | Quercus ilex L. | Quercus pubescens Willd. |

| Other dominant plant species | Quercus coccifera L., Phyllirea latifolia L. | Buxus sempervirens L., Phyllirea latifolial L., Pistacia terebinthus L, Juniperus oxycedrus L. | Acer Monspessulanum L., Cotinus coggygria Scop. |

| Tree density (stems·ha−1) | 3368 | 4500 | 3503 |

| Forest structure | Uneven age (61 years) | Even age (74 years) | Even age (70 years) |

| Rain exclusion device | Permanent system: PVC gutters | Permanent system: PVC gutters | Dynamic system: moving roof device |

| Rain exclusion system dimensions (m2) | 625 | 140 | 300 |

| Rain exclusion device installation | 2009 | 2003 | 2012 |

| Litter Mass Loss | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| d.f. | F-Value | P-Value | |

| Forest type (F) | 2 | 3.2 | * |

| Precipitation treatment (P) | 1 | 13.3 | *** |

| Time (T) | 1 | 43.0 | *** |

| F × P | 2 | 0.2 | |

| F × T | 2 | 4.7 | * |

| P × T | 1 | 5.2 | * |

| F × P × T | 2 | 0.3 | |

| SOC Concentration | SN Concentration | SOC Stock | SN Stock | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d.f. | Chisq | P-Value | Chisq | P-Value | Chisq | P-Value | Chisq | P-Value | |

| Forest type (F) | 2 | 23.0 | *** | 40.2 | *** | 16.6 | *** | 1.6 | |

| Precipitation treatment (P) | 1 | 1.9 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | ||||

| Soil layer (S) | 2 | 1709.5 | *** | 200.0 | *** | 2264.8 | *** | 1892.4 | *** |

| F × P | 2 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 2.2 | ||||

| F × S | 2 | 33.6 | *** | 3.5 | 82.0 | *** | 20.6 | *** | |

| P × S | 1 | 2.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 0.2 | ||||

| F × P × S | 2 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 7.4 | * | 0.0 | |||

| d.f. | F-Value | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total SOC stock | |||

| Forest type (F) | 2 | 6.3 | ** |

| Precipitation treatment (P) | 1 | 0.1 | |

| F × P | 2 | 1.0 | |

| Total SN stock | |||

| Forest type (F) | 2 | 7.8 | *** |

| Precipitation treatment (P) | 1 | 0.2 | |

| F × P | 2 | 2.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santonja, M.; Pereira, S.; Gauquelin, T.; Quer, E.; Simioni, G.; Limousin, J.-M.; Ourcival, J.-M.; Reiter, I.M.; Fernandez, C.; Baldy, V. Experimental Precipitation Reduction Slows Down Litter Decomposition but Exhibits Weak to No Effect on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks in Three Mediterranean Forests of Southern France. Forests 2022, 13, 1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13091485

Santonja M, Pereira S, Gauquelin T, Quer E, Simioni G, Limousin J-M, Ourcival J-M, Reiter IM, Fernandez C, Baldy V. Experimental Precipitation Reduction Slows Down Litter Decomposition but Exhibits Weak to No Effect on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks in Three Mediterranean Forests of Southern France. Forests. 2022; 13(9):1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13091485

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantonja, Mathieu, Susana Pereira, Thierry Gauquelin, Elodie Quer, Guillaume Simioni, Jean-Marc Limousin, Jean-Marc Ourcival, Ilja M. Reiter, Catherine Fernandez, and Virginie Baldy. 2022. "Experimental Precipitation Reduction Slows Down Litter Decomposition but Exhibits Weak to No Effect on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks in Three Mediterranean Forests of Southern France" Forests 13, no. 9: 1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13091485

APA StyleSantonja, M., Pereira, S., Gauquelin, T., Quer, E., Simioni, G., Limousin, J.-M., Ourcival, J.-M., Reiter, I. M., Fernandez, C., & Baldy, V. (2022). Experimental Precipitation Reduction Slows Down Litter Decomposition but Exhibits Weak to No Effect on Soil Organic Carbon and Nitrogen Stocks in Three Mediterranean Forests of Southern France. Forests, 13(9), 1485. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13091485