1. Introduction

Understanding the implementation of public policy has been a difficult problem; public policies are often not implemented on the ground, as they were determined by lawmakers in a parliament or by high-ranking officials of a ministry. Actual processes of policy implementation are far more complex; therefore, enriching the understanding of such processes is of great importance [

1,

2].

In the tropical forest sector, it is common that forest policies are not actually implemented or are implemented in unexpected ways on the ground [

3]. Such observed outcomes could be regarded simply as a “failure” of policy due to a lack of budget and human resources [

4]. Such an account may be at least partly true, given the conditions of tropical developing countries. However, detailed exploration of why and how a certain forest management operation was not implemented will lead to more nuanced understandings of local policy realities in the tropical forest sector.

The present study provides a detailed case study analysis of discretionary operations practiced by frontline forest bureaucrats in Java, Indonesia. Forests in tropical developing countries have been mostly under state ownership due to the nationalization processes in the colonial period [

5,

6]. Forest bureaucrats; i.e., officers working for agencies or departments responsible for state forest management, administer and manage these forests. Their operations have included regulatory measures such as patrols or policing of local people. Recently, in the context of increasing evidence of devolution of forest management rights to local communities [

7,

8], the conventional regulatory role of forest bureaucrats might be weakened, and new tasks such as facilitating community engagement are generally added. In any sense, forest administrators can continuously have a large influence on tropical state forest management in practice. To focus on frontline bureaucrats is of great importance when it comes to why and how a policy is (not) implemented as expected.

One of the influential theories informing the realities of public policy implementation is street-level bureaucracy. Michael Lipsky defined street-level bureaucrats as “public service workers who interact directly with citizens in the course of their jobs, and who have substantial discretion in the execution of their work” [

9]. Examples of street-level bureaucrats include teachers, police officers, social workers, judges, public lawyers, and health workers. According to Lipsky, contrary to the general image of “rigid” bureaucracy, street-level bureaucrats have a large degree of discretion in their daily operations. Such frontline workers may determine the recipients of a public service, may tacitly exclude or pass over certain people for the delivery of a public service, or may give greater access to information related to a public service to certain people within the boundaries of existing laws and regulations. Frontline workers have a significant influence on delivering public services on the ground, and general citizens encounter and experience the state via these frontline workers. The work of street-level bureaucrats can be particularly characterized by the chronic inadequacy of human resources for the tasks and by ambiguity, vagueness, and conflict over expectations of goals and measurement of work performance [

9]. In addition, street-level bureaucrats and service recipients develop contextual relationships, often affected by their everyday lives as well as by certain cultural or ethnic background or social class commonalities. These conditions work as a foundation for discretionary behavior.

However, such discretionary operations are not necessarily negative; rather, discretion may be crucial to making things work in the realities of street-level bureaucrats’ working conditions and relationships with the recipients of public services. Lipsky did not focus on “what street-level bureaucrats

should do”, but instead focused on “what they

did and why” [

10]. In other words, the policies that work are only those that are compatible with the ground realities of frontline bureaucrats. Applying the perspective of street-level bureaucracy and considering how and why discretion is exercised by frontline forest bureaucrats would help us understand the complex realities of policy implementation.

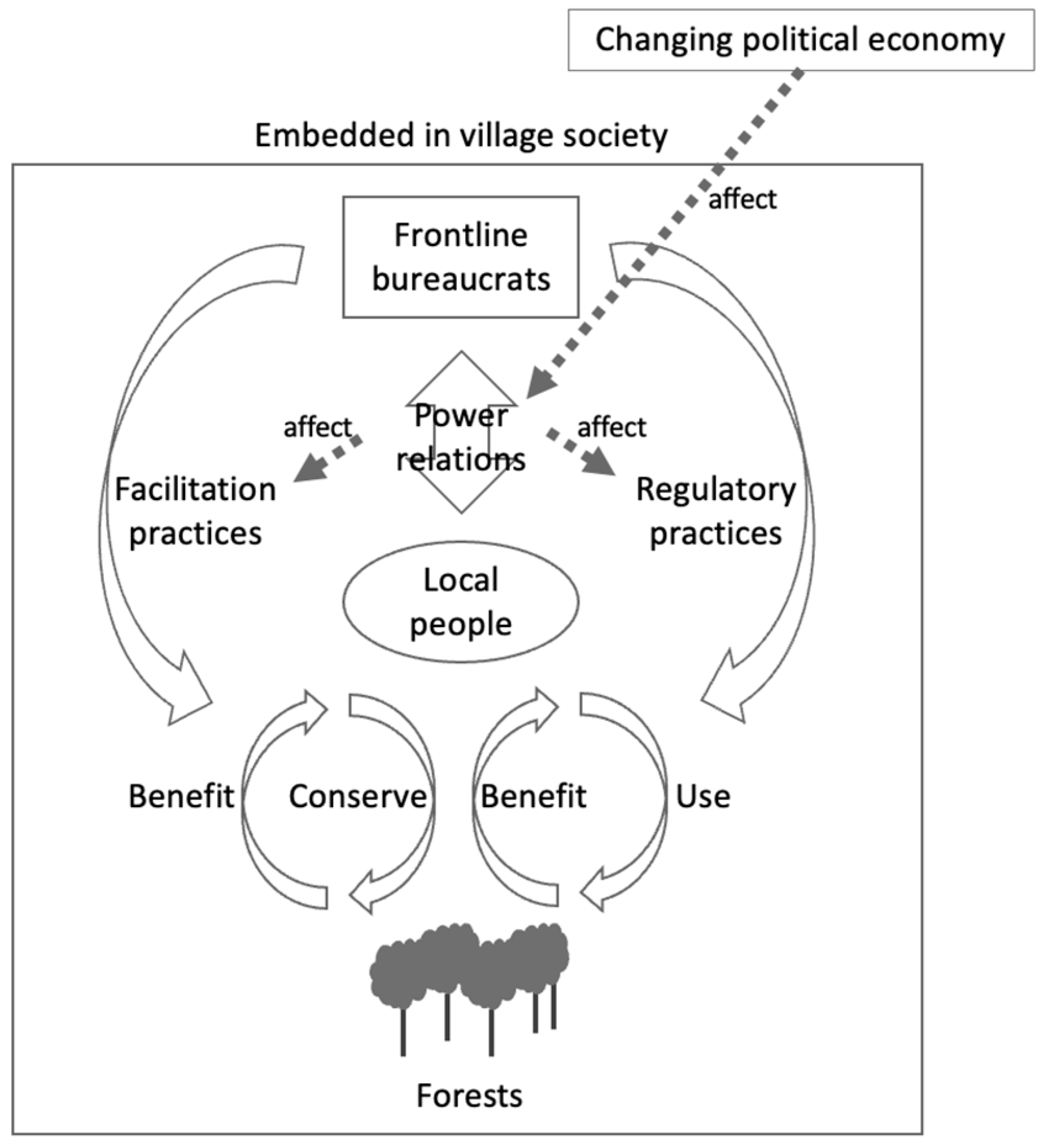

In the following sections, the author will first review previous studies related to street-level bureaucracy and discretionary operations by forest officials in forestry and natural resource management sectors. For a deeper synthesis, the author also reviews studies about developed countries in addition to those about tropical developing countries. The review will identify the importance of making analyses that focus on changing political economy and power relations between forest bureaucracy and local people in contemporary tropical countries. Java in Indonesia was selected as the case study site. Findings obtained through various data collection methods will be presented, followed by discussions about what kinds of policy implications can be derived.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Selection

The present study applied a case study method that focused on a particular sector in a particular locality. In general, case study approaches can effectively deal with how a program is actually implemented [

38]. The present study involved the clarification of actual processes of policy implementation by frontline forest bureaucrats, and hence a case study approach was suitable. Previous studies also applied case study methods in a particular sector and locality [

26,

29].

The present study selected teak plantation regions of Java in Indonesia as the case study site. Unlike other parts of Southeast Asia, a rigid forest administration has been in place in Java since the Dutch colonial period. Since 1972, Perum Perhutani, or the State Forestry Corporation (SFC), has functioned as a forest administration body. The SFC has established and operated an intensive management system for high-value teak (Tectona grandis) plantation forests, with clearly demarcated forestlands, systematic and detailed management plans, and professional foresters.

In terms of demography, Java has high population density (i.e., more than 1000 people/km

2). Intense demand from locals for smallholdings inside forestland is evident. A classic study [

6] characterized the conventional situation of rural Javanese forestry areas as having “rich forests, poor people,” as the SFC’s rigid control over forest resources has typically perpetuated the impoverishment of locals.

The relationship between the forest administration and local communities on Java has changed drastically since 1997. Triggered by political economic turmoil due to the Asian financial crisis and the collapse of the Suharto regime, looting of plantation forests (in the form of illegal logging and unofficial cultivation on forestlands) intensified sharply in the late 1990s [

39]. The illegal logging occurred particularly in teak plantation regions. As the structure established by the SFC became paralyzed, forest management became impossible to control. To cope with the situation, the SFC established

Pergelolaan Sumberdaya Hutan Bersama Masyarakat, or Joint Forest Management (JFM), in 2001. JFM is a community forestry initiative in which committees, known as

Lembaga Masyarakat Desa Hutan, are formed at the village level, and the SFC cooperates with these committees to manage state forests through formal contracts. Official benefit-sharing mechanisms from forestry production represent one of the most distinctive features. However, evaluations of JFM are mixed; a body of evidence indicates ineffective, inequitable implementation conditions and outcomes [

40].

Overall, the above-mentioned political and institutional changes have led to greater bargaining power on the part of the locals counter to the SFC [

41,

42]. This tendency has also been backed by the general trends of democratization in Indonesia after the 2000s. Thus, the author chose teak plantation regions in contemporary Java as a case where the authority and power held by the forest administration has been decreasing while the bargaining power of the locals has been increasing. This case was suitable for using the developed framework to observe how frontline forest bureaucrats manage regulatory and facilitation processes in the changing political economic relations with the locals.

The present study particularly focused on the Randublatung Forest District in Central Java. This forest district is one of the major teak plantation regions in Central Java. Similar to other parts of Java, the state forests in the Randublatung Forest District have been severely degraded, particularly due to widespread illegal logging and unofficial forestland cultivation during the insurgent period of 1997–2003. Before 2003, the extensive looting of forests led to a drastic increase in nonproductive forest areas; however, the damage was not so severe as to denude all forest areas in the district.

In the Randublatung Forest District, JFM has been in place since approximately 2003; as of the beginning of 2018, a total of 34 JFM committees were established, one in each of the 34 villages in the district. According to forest district-wide data for Central Java, the amount of monetary benefit sharing under JFM is largest in Randublatung.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The present study involved various methods of data collection and diverse sources of information to best capture the actualities of frontline forest bureaucrats. Before the data collection process started, the author visited the Randublatung Forest District office of the SFC in August 2016, January 2017, and January 2018 to confirm official documents and statistics related to forest administrative systems.

First, the author conducted an anonymous mail-out questionnaire survey for all field frontline forest bureaucrats in the forest district in January 2018. The present study defined frontline forest bureaucrats as forest guards, foremen, and forest police officers. A total of 267 responses were collected, which was equivalent to 94.7% of the total number of forest guards, foremen, and forest police officers in the district. The topics in the survey that were related to the regulatory aspect included the frequency of encountering forest offenses (i.e., illegal logging, illegal collection of firewood, newly started forestland encroachment, and illegal grazing) in the previous year, experiences of intentionally overlooking such offenses, and reasons for overlooking offenses. The topics in the survey that were related to the facilitation aspect included perceptions of the JFM committees.

Second, the author conducted surveys on 14 randomly selected JFM committees in the Randublatung Forest District in August 2016 and January 2017. Surveys were carried out through in-person interviews with the presidents and other executive members of the committees, and dealt with basic characteristics of the committees, uses of shared benefits in the village, and activities conducted by the committees under JFM.

Third, the author conducted household surveys in a village in January 2018. The village (pseudonymously called Bodang) had extensive evidence of forestland encroachment. The author collected the household-level data from 43 randomly selected respondents. Topics included basic characteristics of the household, livelihood activities, and farming plots outside and inside the forestland.

Fourth, during the period when the author was engaged in the second and third data collection processes in rural areas, participatory observations of the village dairy situation and events related to forest management were made. Observations involved informal conversations with frontline forest bureaucrats and locals. The second, third, and fourth processes provided evidence of how forest policy is implemented on the ground by incorporating villagers’ views and activities, and served as supplementary information to the data collected through mail-out questionnaires. The data collection methods applied are summarized in

Table 1.

Quantitative data were summarized as descriptive statistics to be presented as tables or figures. Regarding the organizational settings of frontline forest bureaucrats, roles among foremen are divided, so foremen of a certain role skipped the questions meant for foremen of another role. As a result, the numbers of respondents for some questions were less than 267. The numbers of valid responses are provided in each table and figure in the Results section. Quantitative information that was recorded in the author’s notebooks was analyzed in terms of the analytical framework.

4. Results

4.1. Administrative Settings of Frontline Forest Bureaucrats at the SFC

Similar to other forest administration bodies across the world, the SFC has a hierarchical organizational structure. The most important unit in local forest management is the forest district (KPH), and the head of a forest district office is the administrator (ADM). Administrators are the top managers in local forest management, and they are not regarded as frontline forest bureaucrats. The territory of a forest district is divided into several sub-districts (BKPH), which are further divided into several resorts (RPH). The heads of a sub-district and a resort are the forest ranger (asper) and the forest guard (mantri), respectively.

Resorts are the lowest unit of administration of the SFC, and their offices are generally located in village areas. A forest guard has several subordinates called foremen (mandor). Foremen are categorized into several types: foremen for seeding, planting, tending, felling, and patrolling. The categories from seeding to felling involve the silvicultural operations needed for teak plantation forests, while patrolling spans all these phases and involves protecting tree standings from illicit felling or extraction.

Apart from these officials, there are several forest police officers (polhut mob) who rush to the scene where/when needed. They are not stationed at any single resort, but rather are a mobile brigade covering the entire forest district.

The present study defined forest guards, foremen, and forest police officers as frontline forest bureaucrats.

Table 2 shows the numbers of these officers in the Randublatung Forest District at the time of the survey (January 2018). It should be noted that there were no special foremen for JFM.

4.2. Regulatory Aspects

4.2.1. Findings from the Questionnaire Results

The SFC explains their strategy of forest protection as “preemptive, preventive, and repressive.” Preemptive measures involve establishing formal and informal relationships with villagers, all the while being respectful of them, in order to detect and monitor any signs of (impending) forest crimes. Specific methods include attending community events, socializing about the importance of forests, and supporting the community in solving problems. The SFC recognizes that the preemptive aspect is of primary importance; a few forest guards told the author that they always keep in mind that frequent visits to villages are important. Close relationships with villagers can lead to greater information provision, such as short-message services from villagers via mobile phones.

Preventive measures include routine patrols by thoroughly roaming the forest areas. Patrolling is one of the most important routine tasks for forest guards and patrolling foremen. They work in shifts, every day, around the clock. Forest guards are responsible for administering patrol activities in their resorts.

Repressive measures involve policing activities after an offense has occurred. Specific tasks include securing the site where a forest offense was perpetrated, searching for or arresting the perpetrators, securing the evidence, and making records. In the Randublatung Forest District, various forest offenses were evident;

Figure 2 shows rough estimates of the frequency of illegal activities. The author’s questionnaire asked the forest guards, foremen for patrolling, and forest police officers—a total of 196 respondents—to score the frequency of encountering illegal activities. The numbers in

Figure 2 indicated that many frontline forest bureaucrats have encountered illegal activities; in particular, approximately 85% of the respondents have encountered illegal timber harvesting/theft at least more than one time in a year.

Repressive measures could become a context wherein discretionary operations within the regulatory aspect are exercised. According to the questionnaire survey, 125 respondents, or approximately 64% of the relevant respondents, answered that they have had experiences of not enforcing regulations of illegal activities.

Figure 3 shows the reasons for overlooking offenses, which included “because it was the first case for the violator”, “because it was small-scale,” and “because the violator was poor.” No respondent answered “because the violator is an acquaintance,” “because the violator has a relationship with an influential person,” or “because the violator gave a bribe.” It should be noted that

Figure 3 represents the answers from frontline forest bureaucrats on the questionnaire, and disparities with their actual actions cannot be confirmed or denied. Even with this taken into consideration, it can be argued that the frontline forest bureaucrats are likely to exercise discretion when they encounter new violators in negligible cases. Cases related to poverty can also be subject to discretion, with a result of not applying strict rules.

4.2.2. Findings from the Village-Level Information

The issue of forestland encroachment was evident in many villages. In the village of Bodang, in the author’s randomly sampled household survey (

n = 43), 69.7% of the respondents answered that their households had cultivation plots, both official and unofficial, on forest lands. The average area of cultivation plots on forestland was 0.76 ha. Here, official cultivation on forestland refers to cultivation plots under

tumpangsari contracts, an agroforestry-cum-reforestation system in which contract farmers plant and tend teak trees on certain plots of forestland [

43]. The contracts between the SFC and farmers last three years. If the cultivation plots fall under the

tumpangsari arrangements, they are considered official. Unofficial cultivation refers to cultivation plots outside the

tumpangsari arrangements. Of the households with cultivation plots on forestland, the percentage of households with plots that were suspected to be unofficial was 90.0%.

From the viewpoint of the SFC, such situations are problematic. Frontline forest bureaucrats did have information on who had encroached with which plots; however, these encroached plots were a fait accompli, and in daily operations, the bureaucrats had not succeeded in dealing with this issue effectively.

When conducting household surveys in Bodang, the author had the opportunity to observe a village meeting held by frontline forest bureaucrats to address the forestland encroachment issue. They had identified people with illegal cultivation plots on forestland and requested them to gather. Around 30 villagers, all men, were present. In addition to forest guards and foremen, a forest ranger (their boss) was also in attendance. The forest ranger and forest guards generously began by mentioning that the forestland was subject to joint management by the SFC and the JFM committee, and would be managed appropriately as forests providing proper ecosystem services. Then, they thanked the villagers’ for their cooperation in planting and growing teak trees with a tumpangsari contract, allowing cultivation for three years. At that point, they stated that the cultivation practice would be discontinued due to the end of the contract period, and for the mutual prosperity of the SFC and JFM, trees would be planted again to reforest the plots. They also said that seedlings to be planted would be prepared by the SFC. They emphasized that the new contract would no longer be effective after three years; after the contract finished, another tumpangsari opportunity might come. Villagers agreed to reforest the plots that they were currently cultivating; i.e., encroached plots. The frontline forest bureaucrats told the author that they had tried the same procedures a few times in this village as well as in other localities, suggesting that this attempt might also be unsuccessful.

Such a method to persuade villagers suggested that the frontline forest bureaucrats did not coercively evict them from the plots on the forestland; rather, the bureaucrats made use of the logic of formal agreement with JFM and asked for cooperation and collaboration for reforestation.

4.3. Facilitation Aspects

4.3.1. Findings from the Questionnaire Results

Since the implementation of JFM in 2001, the role of the SFC has included facilitation and interaction with villagers. Facilitation has been said to be crucial to motivating villagers around forest management and conservation, with proper understandings of the concept of JFM. However, as already mentioned, there was no specific JFM foreman (

Table 2). This indicated that the SFC does not view JFM in the same way as conventional silvicultural and regulatory tasks. Resorts were not in the primary position of administering JFM.

JFM-related issues were managed by the Sub-Section of Joint Forest Management at the forest district office. Officials in this sub-section were essentially stationed at the forest district office to engage in various kinds of desk work. Although they visited villages in keeping with the occasions and tasks, they were outside the present study’s definition of frontline forest bureaucrats. One of their most important tasks was to calculate the amounts of money to be allocated from the SFC’s forestry production to JFM committees; the amounts were determined by considering how much value was earned from each forest compartment after deducting operational costs and other expenditures, and more. This aspect did not have room to exercise discretion.

In addition, the sub-section was also responsible for making agreements with JFM committees about the principles of using shared benefits for each committee (village). The principles for how to use shared benefits were decided every year through official meetings between the staff of the sub-section and the presidents of all JFM committees in the forest district. In 2014, the purpose-wise allocations at the committee (village) level were as follows: 30% for business activities, 15% for village infrastructure, 17% for administrative costs, 15% for forest management, 10% for social purposes, and 13% for contributions for other stakeholders.

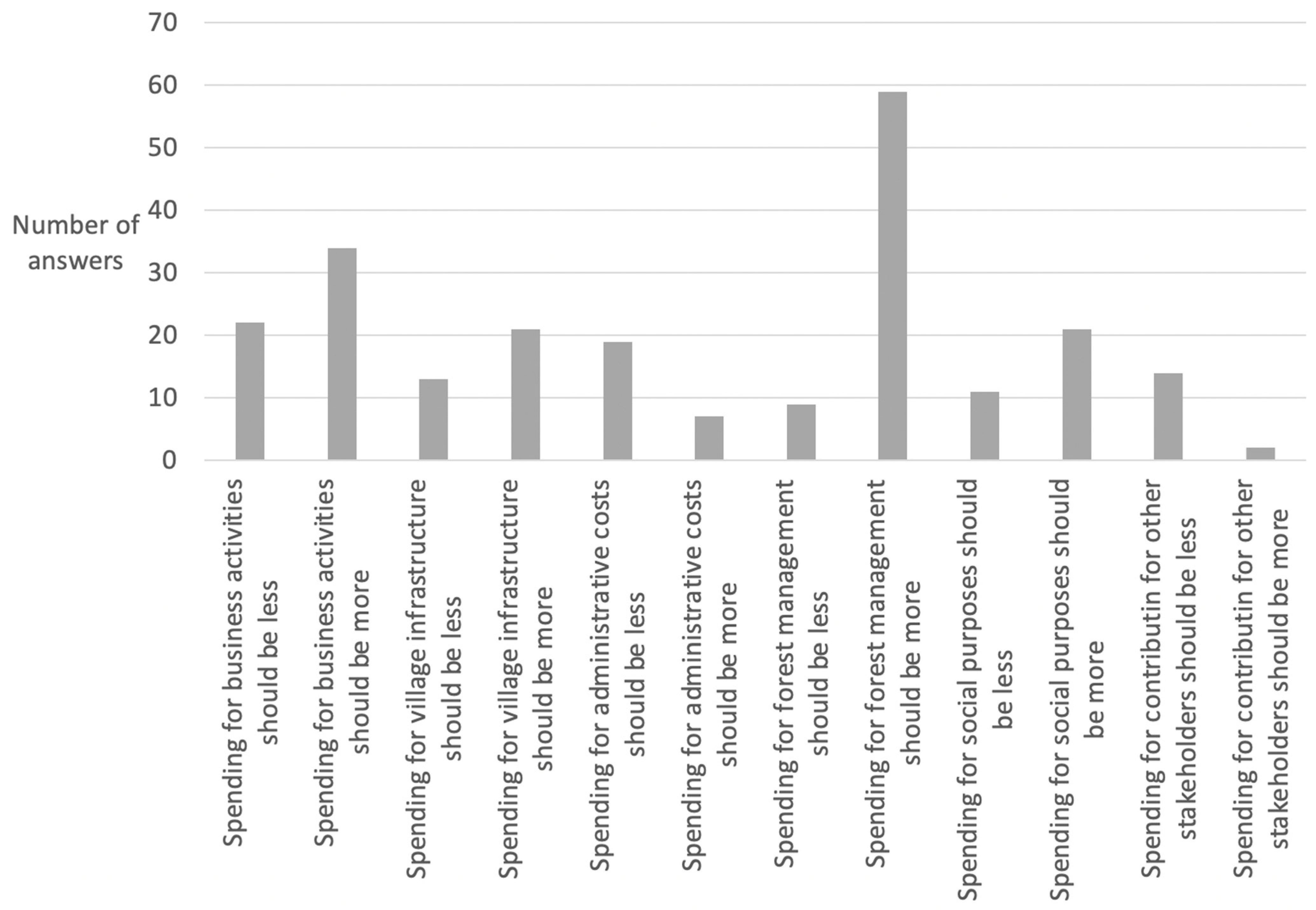

According to the questionnaire results from frontline forest bureaucrats about their opinions of the villagers’ uses of shared benefits under JFM, 143 respondents—or 54% of the 267 respondents—considered that the use of shared benefits under joint forest management is “problematic”; 17% considered it “no problem”, and 30% said “no idea”.

Figure 4 shows the reasons for the choice of “problematic”. “Spending for forest management should be more” received the greatest number of answers. This reflected the forest bureaucrats’ value that the more money is invested in the forest, the better the situation is; from an “ideal” standpoint, the present uses of shared benefits for conducting forest management are insufficient. Additionally, they were also likely to state that “spending for business activities should be more”. This could be interpreted as the bureaucrats considering that local livelihoods should be improved more through JFM committees’ business activities. Overall, these responses indicated that frontline forest bureaucrats were not fully on board with the situation of implementing JFM at the local level; at the very least, their viewpoint was that there is room for improvement.

4.3.2. Findings from the Village-Level Information

According to the author’s survey of 14 JFM committees, the uses of shared benefits in each committee were not exactly effective and equitable. For business activities, non-forestry practices—such as cooperatives, rearing cows or goats, and renting ceremonial tools—had been preferred. Richer committees, with greater amounts of benefit sharing, were likely to have implemented more business activities, but the percentages of business activities that remained in practice by the time of the author’s visits were lower in such committees: many business activities had failed. Benefits from business activities, if any, tended to be pooled among the executive members of the JFM committees, and ordinary villagers had enjoyed few benefits.

In terms of forest management, money from the shared benefits was mostly used to hire villagers as watchmen. In total, 9 committees had conducted patrol activities out of the 14 committees. Of these, only the four richest committees that could afford to pay for watchmen had kept up patrol activities by the time of the author’s visits. This is the context in which questionnaire respondents gave the answers shown in

Figure 4—i.e., frontline forest bureaucrats were likely to believe “spending for forest management should be more” and “spending for business activities should be more”.

However, frontline forest bureaucrats were not likely to share such opinions with villagers. During fieldwork, the author was told by a few forest guards that “uses of shared benefits are a matter of the village.” This indicated that frontline forest bureaucrats thought that because benefit-sharing was an issue under the village’s purview, it would not be appropriate to offer advice or say something about the uses of shared benefits, as such advice could be seen as a type of interference. Although forest rangers and forest guards were generally executive members of committees as supervisors or advisors, they appeared to not advise on or facilitate the use of shared benefits. Consequently, a sort of hesitation among frontline forest bureaucrats was confirmed.

Thus, under JFM, frontline forest bureaucrats were not likely to be involved in facilitation aspects. JFM issues were handled by the staff of the Sub-Section of Joint Forest Management, who are not stationed in resort (lowest level) offices. Except for minimal agreements and directions, neither the staff of the sub-section nor frontline forest bureaucrats had intervened concerning the uses of shared benefits or other JFM activities.

5. Discussion

Various kinds of discretionary operations have been confirmed. Here, the author summarizes the findings categorizing discretion into creative regulatory, passive regulatory, creative facilitation, and passive facilitation (

Table 3).

Frontline forest bureaucrats creatively exercised discretion for their regulatory practices; i.e., non-application of strict regulatory rules and persuasion of forestland encroachers. They tacitly avoided strict enforcement of forest law in view of the local context in terms of the frequency and scale, as well as violators’ economic conditions. In addition, they tried to persuade de facto forestland encroachers to reforest the encroached forestland plots by applying the tumpangsari framework.

At the same time, frontline forest bureaucrats’ regulatory activities also corresponded to the category of passivity. Although there was evidence of creative discretionary operations; i.e., persuasion of locals to reforest the encroached forestland plots, the effectiveness of such measures was doubted. The scale of implementation was also limited. Thus, conduct that caused serious and prolonged damage to forest resources remained largely unaddressed.

Passive facilitation discretion included absence of advice or communication, particularly related to the uses of shared benefits under JFM. Frontline forest bureaucrats did not present clear opinions or intervene in local processes. This situation was quite different from Indian cases [

19,

20,

21], where frontline forest bureaucrats dominate decision making processes. No creative case was found in the facilitation aspect.

There are two important implications of these findings. First, frontline forest bureaucrats had been creative to some extent to accommodate contrasting policy goals of protecting forests and meeting local demands for forests. The creative regulatory operations could be interpreted as attempts at aiming for both policy goals to a maximum extent. However, the absence of creative discretion in the facilitation aspect implied that forest bureaucrats had a value to put regulation above facilitation.

Second, at the same time, frontline forest bureaucrats had been caught up in dilemmas between organizational management strategies and growing demands from and increasing voices of locals, resulting in passive discretion. Passivity in the regulatory and the facilitation aspects are two sides of the same coin, with the key word being hesitation. Absence of interventions and inaction by law enforcement were not due to a lack of budgets or human resources; rather, frontline forest bureaucrats hesitated to intervene in village issues. They applied a method of persuasion to address forestland encroachment issues when, according to the principles of the SFC, repressive measures should have been taken. They acted as though they should not advise villagers on the uses of shared benefits; even when the effectiveness and equity of the uses were doubtful, they simply left them untouched and unresolved.

The author posits that the hesitation of frontline forest bureaucrats to get involved in village issues reflects the increasing bargaining power of locals. Until the 1990s, the SFC’s authority over locals had been strong enough to regulate and control local forest use [

6]. However, the political economic turmoil after 1997 fundamentally changed these conventional relations between forest administrators and locals. Locals dared to clear forests under the authority of the SFC to sell timber and to occupy forestland for cultivation, and it became an uncontrollable situation [

39]. Even after this turmoil was resolved in the beginning of the 2000s, the power relations between the SFC and locals were transformed [

41,

42]. Against this backdrop, frontline forest bureaucrats have felt hesitation, in which their creative discretion is limited. This shift in power relations between forest administrators and locals has also had positive effects. Unlike in many other devolution cases [

20], the SFC had not exercised top-down and exclusive decision making under JFM.

Foresters are, both in the developed and developing worlds, street-level bureaucrats who are demanded to accommodate contradictory policy goals while considering various stakeholders, in which discretion is an indispensable element in actual operations [

11,

29] Absence or deviation of implementation of a policy may not be due to a lack of budgets or human resources alone; rather, it could be a consequence of bureaucrats’ deliberate discretion. In Java’s case, frontline forest bureaucrats’ discretion included both creative and passive forms as a result of their attempts to pursue both forest management and local livelihoods in the context of increasing local bargaining power and growing hesitation among bureaucrats. Policies had been implemented in such subtle relationships between two different policy goals, as well as between frontline forest bureaucrats and locals.

6. Conclusions

The present study explored that tropical frontline forest bureaucrats can exercise various kinds of discretion, and the exercise of discretion would be for coping with contrasting policy goals of forest management and local livelihoods in the context of increasing bargaining power of locals. The study also suggested the importance of examining the wider political economy that generates discretionary operations.

In terms of policy implications, as the fundamental issue may not be a lack of budget or human resources, as were the power relations with locals in Java’s case, increasing the budget or human resources of the forest administration may not directly lead to better situations. Policy options or organizational measures to remove the conditions that result in negative types of discretion should be deliberated based on the realities of frontline forest bureaucrats [

11]. Efforts to minimize gaps between different policy goals and mediating relationships with stakeholders would be important. At the same time, environments in which frontline forest bureaucrats can engage in creative discretionary operations are favorable. To make such a situation happen, foresters’ values and local or societal expectations should converge [

24,

27,

29]. As already mentioned, discretionary operations are inevitable for frontline forest bureaucrats, as they must accommodate contradictory policy goals while considering the demands of various stakeholders. Hence, to encourage and discourage positive and negative kinds of discretion, respectively, it would be a first step to understand the local situations that they are facing and the kinds of discretion that they are exercising.

With regard to the issue of generalization, the SFC in Java is a case where substantive forest administration has been developed with a firm organizational system in which conventional authority has been weakened due to changes in political situations and increasing local bargaining power. However, situations of forest administration differ across regions. For example, there are cases where substantive forest administration systems had not been developed [

44]. Further studies are desirable to accumulate the insights of various locations under different political economic settings.