Informal Employment in the Forest Sector: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (a)

- Those in the informal economy who own and operate economic units, including (i) own-account workers, (ii) employers and (iii) members of cooperatives and of social and solidarity economy units.

- (b)

- Contributing family workers, irrespective of whether they work in economic units in the formal or informal economy.

- (c)

- Employees holding informal jobs in or for formal enterprises, or in or for economic units in the informal economy, including, but not limited to, those in subcontracting and in supply chains, or as paid domestic workers employed by households.

- (d)

- Workers in unrecognized or unregulated employment relationships.

- (1)

- How did the magnitude of informal employment in the forest sector (forestry and logging, wood industry and paper industry) change over time?

- (2)

- Which factors cause and characterize informal employment in the forest sector?

- (3)

- What are the socioeconomic effects of informal employment in the forest sector?

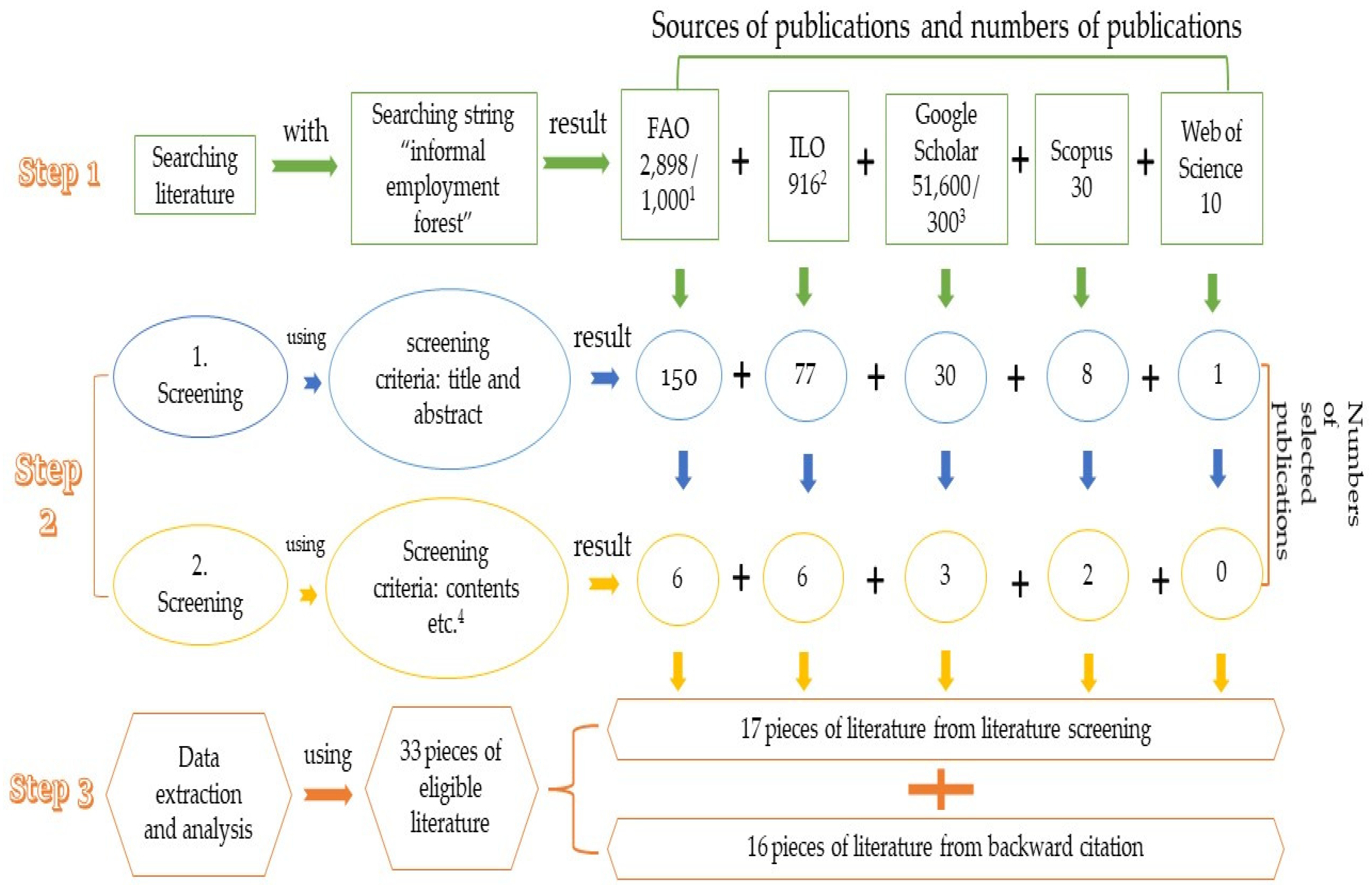

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Source Identification and Search Strategy

- Search string 1: informal AND employment;

- Search string 2: informal OR employment;

- Search string 3: the forest sector;

- Search string 4: informal employment in forest;

- Search string 5: informal AND employment AND in forest;

- Search string 6: informal OR employment OR in forest;

- Search string 7: informal employment forest;

- Search string 8: informal AND employment AND forest;

- Search string 9: informal OR employment OR forest.

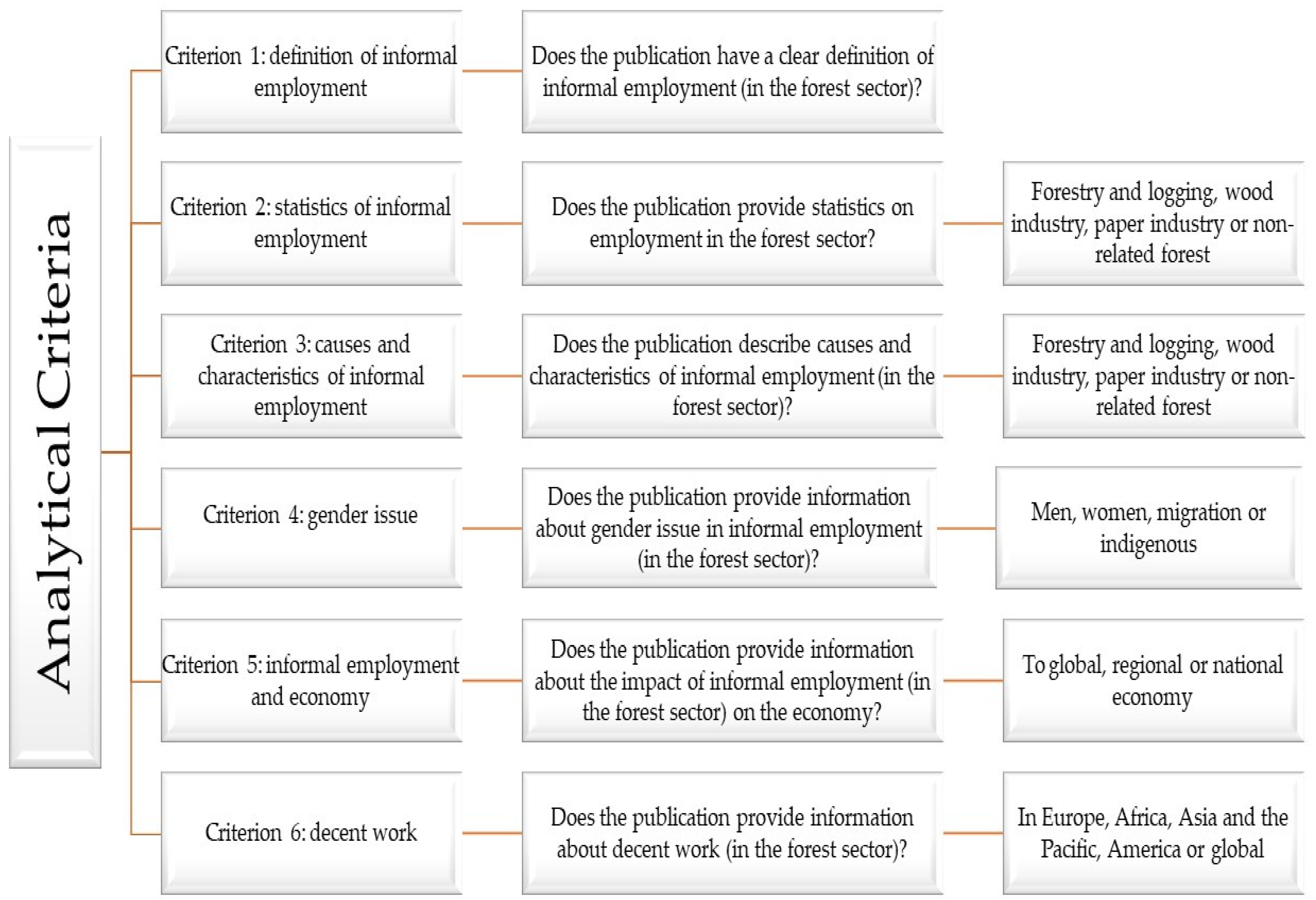

2.2. Literature Screening

3. Results

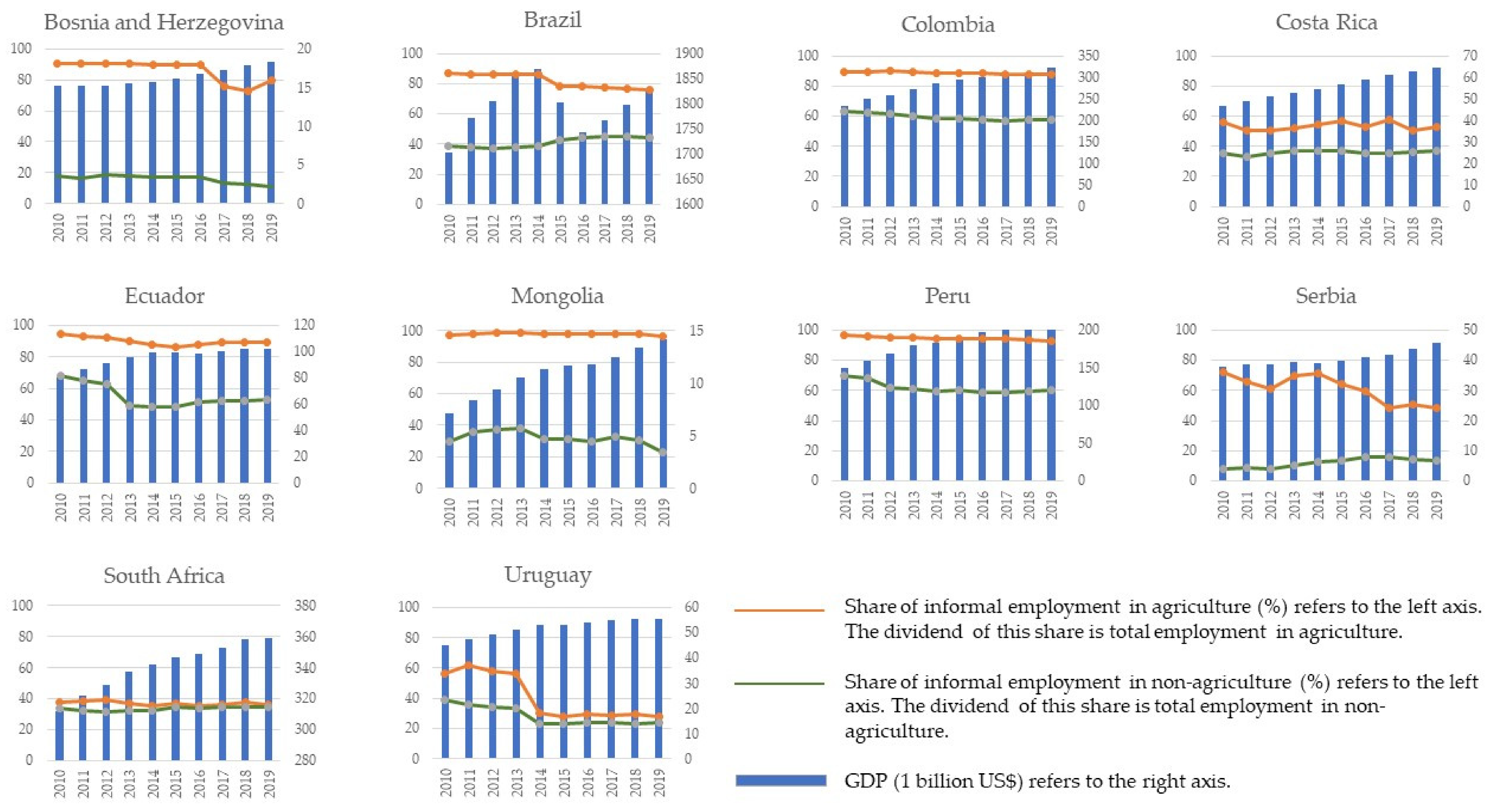

3.1. The Magnitude of Informal Employment in the Forest Sector

3.2. Causes of Informal Employment in the Forest Sector

3.2.1. Poverty and Flexibility

3.2.2. Education and Training

3.2.3. Migration

3.3. Characteristics of Informal Employment in the Forest Sector

3.3.1. Security Deficits

- ◆

- Labor market security. Informal employment lacks employment opportunities, such as high-level employment, and access to public infrastructure.

- ◆

- Employment security. Legal and social protection for pension and maternity, social protection against occupational accidents and illnesses, protection against arbitrary dismissal, regulation on hiring and firing, employment stability compatible with economic dynamism are not available for informal employment.

- ◆

- Skill reproduction security. Training, apprenticeships and access to new technology and equipment are very limited to informal employment. The majority of workers in the forest sector has inadequate skills and qualifications [24], and among informal workers this situation is even worse. The unwillingness of enterprises to provide training has exacerbated the skill enhancement of informal workers.

- ◆

- Income security. Informal workers often have unstable and insufficient income. Many can be described as “working poor”. One study on the informal carpentry sector in Sudan [27] found that 88% of the enterprises employed only 1.5 workers on average and 12% of the enterprisers employed 3 workers. The workers were mostly unpaid or poorly paid apprentices. Workers in the sector were only employed when there is heavy workload.

- ◆

- Representation security. Informal workers are not represented by trade unions and have no voice there. Without trade unions and social dialogue, informal workers cannot claim their rights at work and even do not know their rights. This has further deteriorated the plight of informal workers.

3.3.2. Occupational Accidents and Illnesses

3.3.3. Gender and Informal Employment in the Forest Sector

3.4. Socioeconomic Effects of Informal Employment in the Forest Sector

3.4.1. Working Poverty

3.4.2. Negative Effects of Occupational Accidents and Illnesses

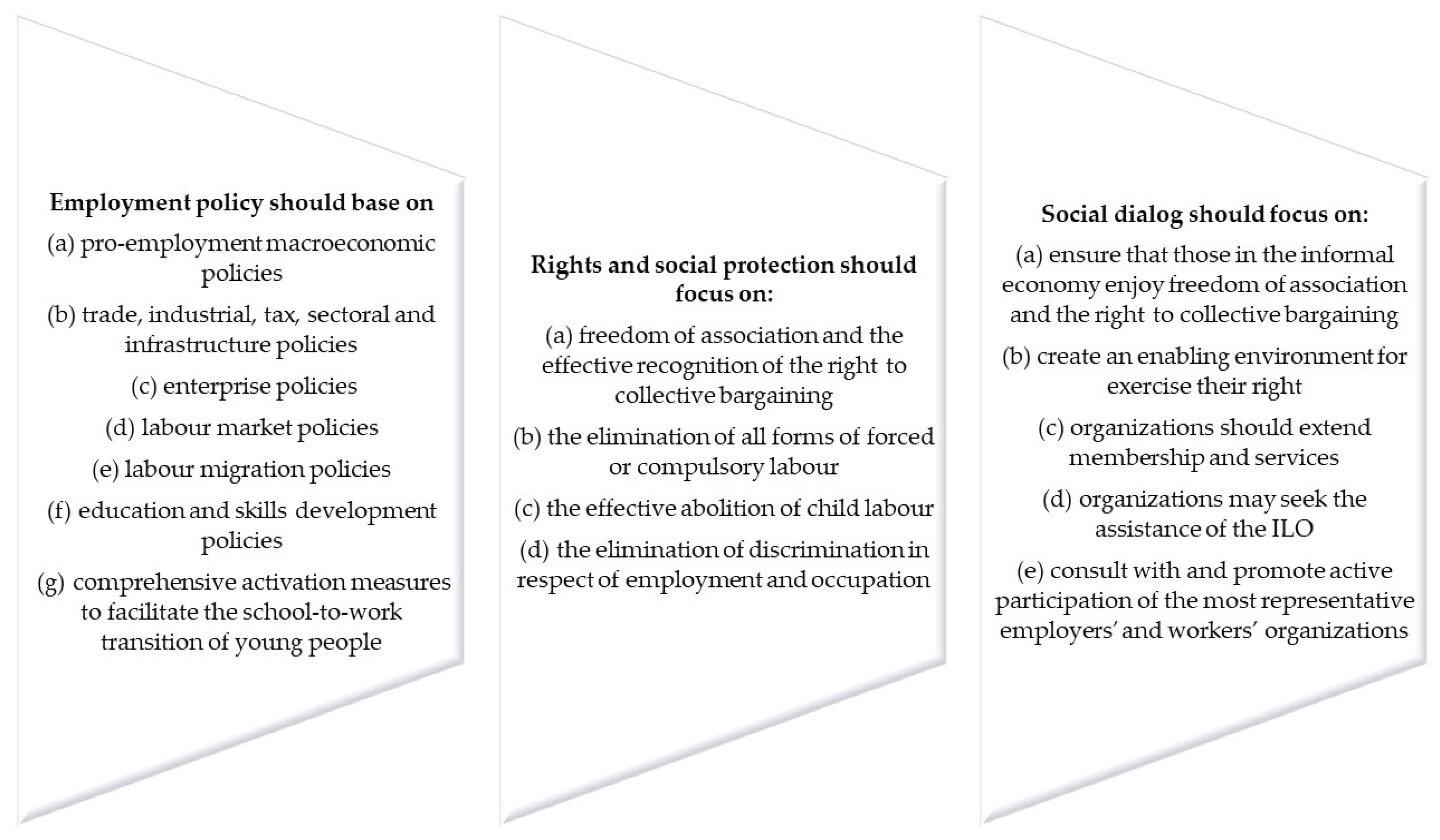

3.5. Instruments to Mitigate Informal Employment

Promotion of Decent Work

- Goal 1: Promoting opportunities

- Strategy 1.1—promoting employment-oriented growth;

- Strategy 1.2—promoting a supportive environment;

- Strategy 1.3—increasing access and competitiveness;

- Strategy 1.4—improving skills and technologies.

- Goal 2: Securing rights

- Strategy 2.1—securing rights of informal wage workers;

- Strategy 2.2—securing rights of the self-employed.

- Goal 3: Promoting protection

- Strategy 3.1—promoting protection against common contingencies;

- Strategy 3.2—promoting protection for migrant workers.

- Goal 4: Promoting voice

- Strategy 4.1—organizing informal workers;

- Strategy 4.2—promoting collective bargaining;

- Strategy 4.3—building international alliances.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ILO. Informal Economy (Employment Promotion). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/employment-promotion/informal-economy/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- ILO. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture, 3rd ed.; International Labour Office (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-92-2-131580-3/978-92-2-131581-0. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. International Journal of Labour Research; International Labour Office (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISSN 2076-9806. ISBN 978-92-2-031368-8/978-92-2-031367-1. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Decent Work and the Informal Economy. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/public/english/standards/relm/ilc/ilc90/pdf/rep-vi.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- ILO. Guidelines Concerning a Statistical Definition of Informal Employment. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/statistics-and-databases/standards-and-guidelines/guidelines-adopted-by-international-conferences-of-labour-statisticians/WCMS_087622/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Ahn, P.-S.; Ahn, Y. Organising Experiences and Experiments among Indian Trade Unions: Concepts, Processes and Showcases. Indian J. Labour Econ. 2012, 55, 573–593. [Google Scholar]

- ILOSTAT. Labour Statistics Glossary—ILOSTAT. Available online: https://ilostat.ilo.org/resources/concepts-and-definitions/glossary/ (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- ILC. Recommendation No. 204 Concerning the Transition from the Informal to the Formal Economy. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/ilc/ILCSessions/previous-sessions/104/texts-adopted/WCMS_377774/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 29 December 2021).

- FAO. State of World’s Forests 2014; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; ISBN 978-92-5-108269-0/978-92-5-108270-6. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2020; International Labour Office (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-92-2-031408-1/978-92-2-031407-4. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundesanstalt für Arbeitsschutz und Arbeitsmedizin. Leitfaden für die Erarbeitung von Scoping Reviews, Projektteam, Psychische Ge-sundheit in der Arbeitswelt. Available online: https://www.baua.de/DE/Themen/Arbeit-und-Gesundheit/Psychische-Gesundheit/Projekt-Psychische-Gesundheit-in-der-Arbeitswelt/pdf/Leitfaden-Scoping-Reviews.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2 (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Garland, J.J. Accident Reporting and Analysis in Forestry: Guidance on Increasing the Safety of Forest Work; Forestry Working Paper No. 2; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Contribution of the Forestry Sector to National Economies, 1990–2011; Forest Finance Working Paper FSFM/ACC/09; Lebedys, A., Li, Y., Eds.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Decent Work and Sustainable Development Goals in Viet Nam—Country Profile; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 9789220314487/978-92-2-0314494. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Decent Work in Forestry. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/economic-and-social-development/rural-development/WCMS_437197/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- FAO. Gender, Rural Livelihoods and Forestry: Assessment of Gender Issues in Kosovo’s Forestry; FAO: Pristina, Kosovo, 2017; ISBN 978-92-5-109797-7. [Google Scholar]

- Renner, M.; Sweeney, S.; Kubit, J.; Mastny, L. Green Jobs: Towards Decent Work in a Sustainable. Available online: http://sustainability.wfu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/Worldwatch_Green-Jobs-Working-for-People-and-Environment-Report-2009.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

- Osei-Tutu, P.; Nketiah, K.; Kyereh, B.; Owusu-Ansah, M.; Faniyan, J. Hidden Forestry Revealed: Characteristics, Constraints and Opportunities for Small and Medium Forest Enterprises in Ghana; IIED Small and Medium Forest Enterprise Series No. 27; Tropenbos International and International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.A.; Vanek, J.; Carr, M. Mainstreaming Informal Employment and Gender in Poverty Reduction: A Handbook for Policy-Makers and Other Stakeholders; Commonwealth Secretariat and International Development Research Centre: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 0850927978. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, J.; Cedergren, J.; Eliasson, L.; van Hensbergen, H.; McEwan, A.; Wästerlund, D. Occupational Safety and Health in Forest Harvesting and Silviculture—A Compendium for Practitioners and Instructors; Forestry Working Paper No. 14; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, P.-S. Organizing for Decent Work in the Informal Economy: Strategies, Methods and Practices; Ahn, P.-S., Ed.; International Labour Office, Subregional Office for South Asia (SRO), Bureau for Workers’ Activities (ACTRAV) (ILO): New Delhi, Italy, 2007; ISBN 978-92-2-120045-1/978-92-2-120046-8. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Productive and Safe Work in Forestry: Key Issues and Policy Options to Promote Productive, Decent Jobs in the Forestry Sector. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/employment/units/rural-development/WCMS_158989/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Estruch, E.; Rapone, C. Promoting Decent Employment in Forestry for Improved Nutrition and Food Security: Background Paper for the International Conference on Forests for Food and Nutrition; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Sectoral Meeting on Promoting Decent Work and Safety and Health in Forestry (Geneva, 6–10 May 2019); International Labour Office, Sectoral Policies Department (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-92-2-133966-3/978-92-2-133967-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ackerknecht, C. Work in the Forestry Sector: Some Issues for a Changing Workforce. Unasylva 2010, 61, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, Y.O.; Pettenella, D. The Contribution of Small-Scale Forestry-Based Enterprises to the Rural Economy in the Developing World: The Case of the Informal Carpentry Sector, Sudan. Small-Scale For. 2013, 12, 461–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, M.; Chen, M.A. Globalization and the Informal Economy: How Global Trade and Investment Impact on the Working Poor. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/employment/Whatwedo/Publications/WCMS_122053/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 29 November 2021).

- FAO. State of the World’s Forests 2007; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2007; ISBN 978-92-5-105586-1. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020: Main Report; FAO: Rome, 2020; ISBN 978-92-5-132974-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE; FAO. Forest Sector Workforce in the UNECE Region: Overview of the Social and Economic Trends with Impact on the Forest Sector; Geneva Timber and Forest Discussion Paper 76. ECE/TIM/DP/76; Forestry and Timber Section, United Nation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-92-1-004788-3. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Safety and Health in Forestry Work: An ILO Code of Practice; 1998/Code of Practice/, /Occupational Safety/, /Occupational Health/, /Forestry/, 13.04.2; International Labour Office (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1998; ISBN 92-2-110826-0. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. International Year of Forests 2011: What about the Labour Aspects of Forestry? Available online: https://www.ilo.org/sector/Resources/publications/WCMS_160879/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 11 September 2020).

- ILO. The Informal Economy and Decent Work: A Policy Resource Guide, Supporting Transitions to Formality; International Labour Office, Employment Policy Department (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; ISBN 978-92-2-126962-5/978-92-2-126963-2/978-92-2-126964-9. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2019; International Labour Office (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-92-2-132952-7/978-92-2-132953-4. [Google Scholar]

- Karabchuk, T.; Zabirova, A. Informal Employment in Service Industries: Estimations from Nationally Representative Labour Force Survey Data of Russian Federation. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 742–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussmanns, R.; Jeu, B.d. ILO Compendium of Official Statistics on Employment in the Informal Sector; International Labour Organization (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/public/libdoc/ilo/2002/102B09_137_engl.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2022).

- Rothboeck, S.; Kring, T. Promoting Transition towards Formalization: Selected Good Practices in Four Sectors; ILO DWT for South Asia and Country Office for India; International Labour Office (ILO): New Delhi, India, 2014; ISBN 978-92-2-129303-3/978-92-2-129304-0. [Google Scholar]

- Slonimczyk, F. Informal employment in emerging and transition economies. IZA World of Labor 2014, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IIED. Unlocking the Potential of Small and Medium Forest Enterprises. Available online: https://www.profor.info/sites/profor.info/files/PROFOR_Brief_ForestSMEs.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- ILO. Skills and Jobs Mismatches in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; International Labour Office (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-92-2-131561-2/978-92-2-131562-9. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Promoting Employment and Decent Work in A Changing Landscape. In Proceedings of the 109th Session of the International Labour Conference, Geneva, Switzerland, 25 May–5 June 2020; International Labour Office (ILO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. ISBN 978-92-2-132386-0/978-92-2-132387-7. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. Decent Work Country Programmes (DWCPs). Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/how-the-ilo-works/departments-and-offices/program/dwcp/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- FAO. Decent Rural Employment. Available online: https://www.fao.org/rural-employment/background/en/ (accessed on 24 January 2022).

- Lippe, R.S.; Cui, S.; Schweinle, J. Estimating Global Forest-Based Employment. Forests 2021, 12, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sequence Number | Author | Year of Publication | Quality of Paper | Geographical Coverage | Criterion 1 Definition | Criterion 2 Statistics | Criterion 3 Causes and Characteristics | Criterion 4 Gender Issue | Criterion 5 Economy | Criterion 6 Decent Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [13] | Garland, J. J. | 2018 | grey literature | global | yes | yes, global | ||||

| 2 [14] | FAO | 2014 | grey literature | global | yes, global | |||||

| 3 [15] | ILO | 2019 | grey literature | Vietnam | yes | yes, Asia | ||||

| 4 [16] | ILO | 2019 | grey literature | global | yes | yes | yes, global | |||

| 5 [17] | FAO | 2017 | grey literature | Kosovo | yes | |||||

| 6 [18] | Renner, M. et al. | 2008 | grey literature | global | yes, non-related forest | |||||

| 7 [19] | Osei-Tutu, P. et al. | 2010 | grey literature | Ghana | yes, SMEs | |||||

| 8 [20] | Chen, M.A. et al. | 2004 | book | global | yes | yes, global | yes, global | |||

| 9 [21] | Garland J. et al. | 2020 | grey literature | global | yes, global | |||||

| 10 [22] | Ahn, P.-S. | 2007 | grey literature | global | yes | |||||

| 11 [23] | ILO | 2011 | grey literature | global | yes, global | |||||

| 12 [24] | Estruch, E.; Rapone, C. | 2013 | grey literature | global | yes, global | |||||

| 13 [25] | ILO | 2019 | grey literature | global | yes | yes, global | ||||

| 14 [9] | FAO | 2014 | grey literature | global | yes, non-related forest | yes | ||||

| 15 [2] | ILO | 2018 | grey literature | global | yes | |||||

| 16 [26] | Ackerknecht, C. | 2010 | grey literature | global | yes | yes, global | ||||

| 17 [8] | ILC | 2015 | grey literature | global | yes | yes, global |

| Sequence Number | Author | Year of Publication | Quality of Paper | Geographical Coverage | Criterion 1 Definition | Criterion 2 Statistics | Criterion 3 Causes and Characteristics | Criterion 4 Gender Issue | Criterion 5 Economy | Criterion 6 Decent Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 [27] | Adam, Y.O.; Pettenella, D. | 2013 | peer-reviewed | global | yes, SMEs | |||||

| 19 [28] | Carr, M.; Chen, M.A. | 2001 | grey literature | global | yes | yes | yes, global | |||

| 20 [29] | FAO | 2007 | grey literature | global | yes, global | |||||

| 21 [30] | FAO | 2020 | grey literature | global | yes | yes | yes, global | |||

| 22 [31] | UNECE and FAO | 2020 | grey literature | global | yes | yes | yes, global | |||

| 23 [32] | ILO | 1998 | grey literature | global | yes | yes, global | ||||

| 24 [4] | ILO | 2002 | grey literature | global | yes | yes, global | ||||

| 25 [33] | ILO | 2011 | grey literature | global | yes | yes, global | ||||

| 26 [34] | ILO | 2013 | grey literature | global | yes | yes | yes, global | |||

| 27 [3] | ILO | 2019 | grey literature | global | yes | yes, global | ||||

| 28 [35] | ILO | 2019 | grey literature | global | yes | yes, global | ||||

| 29 [36] | Karabchuk, T.; Zabirova, A. | 2018 | grey literature | global | yes, global | |||||

| 30 [37] | Hussmanns, R.; Jeu, B.d. | 2002 | grey literature | global | yes | yes | ||||

| 31 [38] | Rothboeck, S.; Kring, T. | 2014 | grey literature | global | yes | yes, global | ||||

| 32 [39] | Slonimczyk, F. | 2014 | grey literature | global | yes | |||||

| 33 [40] | IIED | 2018 | grey literature | global | yes, SMEs |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Brazil | Colombia | Costa Rica | Ecuador | Mongolia | Peru | Serbia | South Africa | Uruguay | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 271.4 | -- | 12,909.5 | 722.0 | 4104.1 | 538.9 | 12,145.1 | 542.6 | 4749.5 | 637.5 |

| 2011 | 252.0 | 41,811.8 | 13,247.3 | 635.5 | 3973.2 | 583.9 | 12,077.1 | 464.1 | 4654.5 | 629.5 |

| 2012 | 274.1 | 41,637.7 | 13,608.5 | 732.3 | 3984.4 | 618.7 | 11,775.9 | 421.2 | 4630.1 | 565.7 |

| 2013 | 258.9 | 41,522.7 | 13,524.9 | 785.2 | 4016.6 | 621.4 | 11,708.7 | 526.9 | 4848.9 | 571.6 |

| 2014 | 237.7 | 43,340.1 | 13,473.9 | 801.8 | 3928.6 | 553.2 | 11,586.9 | 628.9 | 4921.2 | 390.9 |

| 2015 | 247.5 | 41,857.5 | 13,794.5 | 817.6 | 4162.1 | 575.5 | 11,717.4 | 605.2 | 5473.1 | 393.7 |

| 2016 | 244.2 | 41,151.7 | 13,733.7 | 755.8 | 4561.3 | 581.5 | 11,770.2 | 657.5 | 5413.4 | 403.7 |

| 2017 | 202.5 | 42,303.6 | 13,769.9 | 783.6 | 4855.6 | 635.3 | 11,896.2 | 605.1 | 5607.9 | 396.2 |

| 2018 | 182.1 | 43,320.6 | 13,946.1 | 801.3 | 4870.2 | 611.4 | 12,178.8 | 560.9 | 5792.8 | 391.8 |

| 2019 | 185.5 | 44,311.5 | 13,755.0 | 843.7 | 4984.2 | 475.7 | 12,338.7 | 541.7 | 5747.8 | 389.8 |

| 2020 | 167.7 | 39,919.8 | -- | 709.3 | -- | 481.3 | 11,038.0 | 491.6 | 4798.2 | -- |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, S.; Lippe, R.S.; Schweinle, J. Informal Employment in the Forest Sector: A Scoping Review. Forests 2022, 13, 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13030460

Cui S, Lippe RS, Schweinle J. Informal Employment in the Forest Sector: A Scoping Review. Forests. 2022; 13(3):460. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13030460

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Shannon, Rattiya Suddeephong Lippe, and Jörg Schweinle. 2022. "Informal Employment in the Forest Sector: A Scoping Review" Forests 13, no. 3: 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13030460

APA StyleCui, S., Lippe, R. S., & Schweinle, J. (2022). Informal Employment in the Forest Sector: A Scoping Review. Forests, 13(3), 460. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13030460