The Effectiveness of the Ecological Forest Rangers Policy in Southwest China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

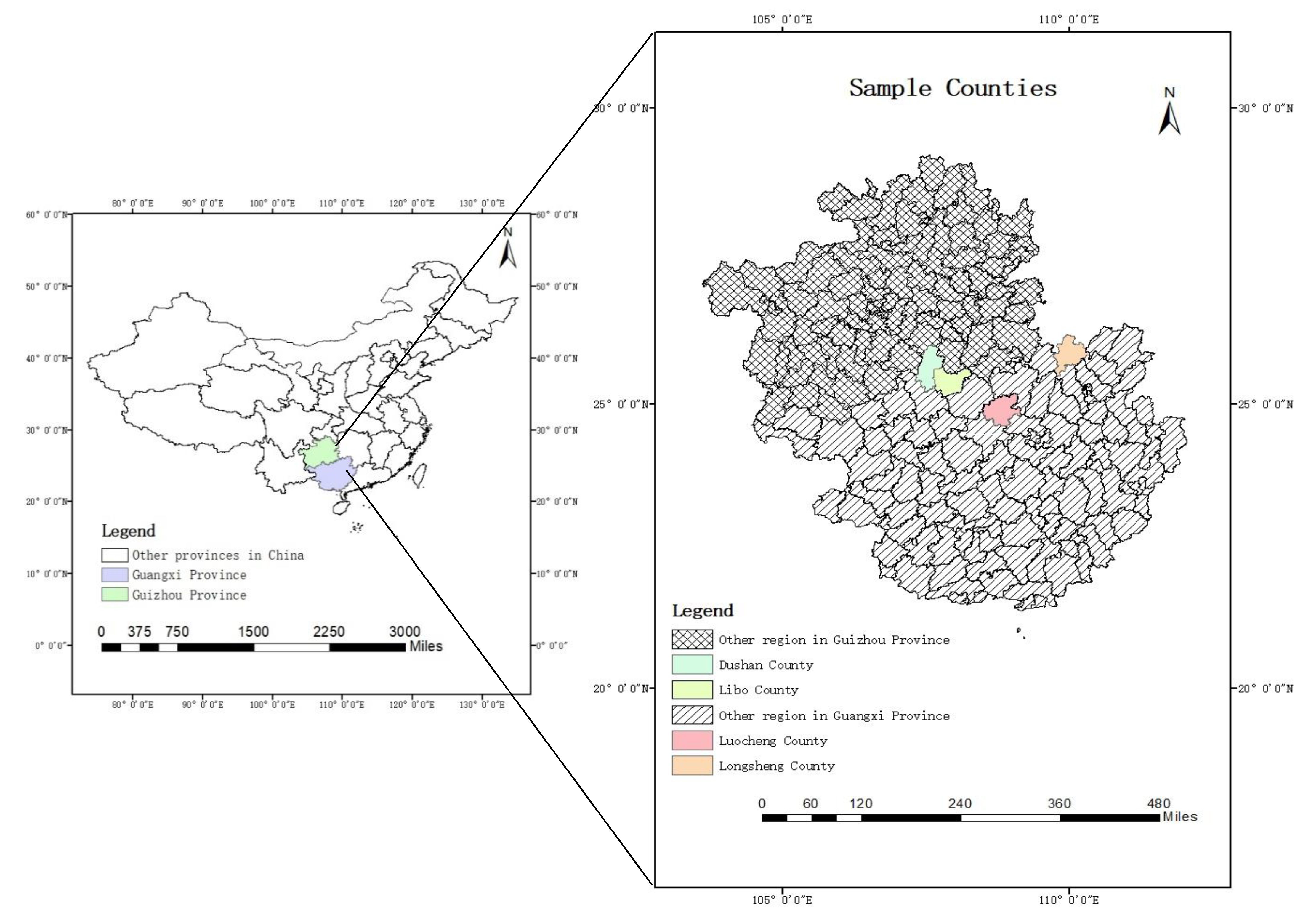

2.1. Study Areas

2.2. Data and Processing

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Ecological Forest Rangers

3.2. Short-Term Effectiveness of the EFRs Policy in Poverty Alleviation

3.3. Sustainability of the EFRs Policy in Income Growth

4. Discussion

4.1. Determinants of the Successful Policy Implementation

4.2. Implications

4.3. Limitation and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Ecological Forest Rangers in China | Forest Rangers In the US [21] |

|---|---|---|

| Contents |

|

|

| Place |

|

|

| Working Time |

|

|

| Remuneration or Salary |

|

|

References

- Poffenberger, M. Restoring and Conserving Khasi Forests: A Community-Based REDD Strategy from Northeast India. Forests 2015, 6, 4477–4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, W.; Galloway, G.; Katila, P.; Pacheco, P. Incentives and Constraints of Community and Smallholder Forestry. Forests 2016, 7, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuits, E. Transnational self-help networks and community forestry: A theoretical framework. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 58, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelsen, A.; Jagger, P.; Babigumira, R.; Belcher, B.; Hogarth, N.J.; Bauch, S.; Börner, J.; Smith-Hall, C.; Wunder, S. Environmental Income and Rural Livelihoods: A Global-Comparative Analysis. World Dev. 2014, 64, S12–S28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jong, W.; Pokorny, B.; Katila, P.; Galloway, G.; Pacheco, P. Community Forestry and the Sustainable Development Goals: A Two Way Street. Forests 2018, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, L.V.; Watkins, C.; Agrawal, A. Forest contributions to livelihoods in changing agriculture-forest landscapes. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 84, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, C.; Holmes, T.; Jackson, A. Forestry Policy, Conservation Activities, and Ecosystem Services in the Remote Misuku Hills of Malawi. Forests 2019, 10, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, R.K.; Neupane, P.R.; Tiwari, K.R.; Köhl, M. Assessing the sustainability in community based forestry: A case from Nepal. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 58, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktan, M.R.; Norbu, L.; Choden, K. Can community forestry contribute to household income and sustainable forestry practices in rural area? A case study from Tshapey and Zariphensum in Bhutan. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 62, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronkleton, P.; Bray, D.B.; Medina, G. Community Forest Management and the Emergence of Multi-Scale Governance Institutions: Lessons for REDD+ Development from Mexico, Brazil and Bolivia. Forests 2011, 2, 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Roberts, D.A.; Stow, D.A.; An, L.; Zhao, Q. Green Vegetation Cover Has Steadily Increased since Establishment of Community Forests in Western Chitwan, Nepal. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, E.A.; Kainer, K.A.; Sierra-Huelsz, J.A.; Negreros-Castillo, P.; Rodriguez-Ward, D.; DiGiano, M. Endurance and Adaptation of Community Forest Management in Quintana Roo, Mexico. Forests 2015, 6, 4295–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandit, R.; Bevilacqua, E. Forest users and environmental impacts of community forestry in the hills of Nepal. For. Policy Econ. 2011, 13, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurer, M.; Gritten, D.; Than, M.M. Community Forestry for Livelihoods: Benefiting from Myanmar’s Mangroves. Forests 2018, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baynes, J.; Herbohn, J.; Smith, C.; Fisher, R.; Bray, D. Key factors which influence the success of community forestry in developing countries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 35, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.D.; Bigsby, H.; MacDonald, I. How can poor and disadvantaged households get an opportunity to become a leader in community forestry in Nepal? For. Policy Econ. 2015, 52, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunam, R.K.; McCarthy, J.F. Advancing equity in community forestry: Recognition of the poor matters. Int. For. Rev. 2010, 12, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritten, D.; Greijmans, M.; Lewis, S.R.; Sokchea, T.; Atkinson, J.; Quang, T.N.; Poudyal, B.; Chapagain, B.; Sapkota, L.M.; Mohns, B.; et al. An Uneven Playing Field: Regulatory Barriers to Communities Making a Living from the Timber from Their Forests–Examples from Cambodia, Nepal and Vietnam. Forests 2015, 6, 3433–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulations on the Management of Ecological Forest Rangers for the Impoverished Population. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/ghzj/4790/20200611/165123836161516.html (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Anderson, J.; Mehta, S.; Epelu, E.; Cohen, B. Managing leftovers: Does community forestry increase secure and equitable access to valuable resources for the rural poor? For. Policy Econ. 2015, 58, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Is a Forest Ranger. Available online: http://www.environmentalscience.org/career/forest-ranger (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Yan, Z.; Wei, F.; Chen, Y.; Deng, X.; Qi, Y. The Policy of Ecological Forest Rangers (EFRs) for the Poor: Goal Positioning and Realistic Choices—Evidence from the Re-Employment Behavior of EFRs in Sichuan, China. Land 2020, 9, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Press Conference on Ecological Forest Rangers Held by the State Council Information Office, P.R.C. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/main/5962/20201202/170013661790253.html (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Zhao, Y.; Han, R.; Cui, N.; Yang, J.; Guo, L. The Impact of Urbanization on Ecosystem Health in Typical Karst Areas: A Case Study of Liupanshui City, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrovšek, F.; Knez, M.; Kogovšek, J.; Mihevc, A.; Mulec, J.; Perne, M.; Petrič, M.; Pipan, T.; Prelovšek, M.; Slabe, T.; et al. Development challenges in karst regions: Sustainable land use planning in the karst of Slovenia. Carbonates Evaporites 2011, 26, 365–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Z.; Yan, L.; Li, B. Quantitative Evaluation of Ecosystem Health in a Karst Area of South China. Sustainability 2016, 8, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.C.; Lian, Y.Q.; Qin, X.Q. Rocky desertification in Southwest China: Impacts, causes, and restoration. Earth Sci. Rev. 2014, 132, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Yu, L.; Huang, Z. Variation of Leaf Carbon Isotope in Plants in Different Lithological Habitats in a Karst Area. Forests 2019, 10, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Hu, B.; Yan, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, K.; Tang, C.; Xie, B. Dynamic Evolution of the Ecological Carrying Capacity of Poverty-Stricken Karst Counties Based on Ecological Footprints: A Case Study in Northwestern Guangxi, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; Wang, K.; Brandt, M.; Yue, Y.; Liao, C.; Fensholt, R. Assessing Future Vegetation Trends and Restoration Prospects in the Karst Regions of Southwest China. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, T.; Li, Q.; Cao, J. The Characteristics of Soil C, N, and P Stoichiometric Ratios as Affected by Geological Background in a Karst Graben Area, Southwest China. Forests 2019, 10, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Xing, X.; Fan, S.; Cao, Y.; Dong, L.; Chen, D. Karren Habitat as the Key in Influencing Plant Distribution and Species Diversity in Shilin Geopark, Southwest China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attachment: Regulations on the Management of Ecological Forest Rangers (Draft for Consultation). Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/main/153/20200721/154705812151772.html (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Gelo, D.; Koch, S.F. Does one size fit all? Heterogeneity in the valuation of community forestry programs. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dokken, T.; Caplow, S.; Angelsen, A.; Sunderlin, W.D. Tenure Issues in REDD+ Pilot Project Sites in Tanzania. Forests 2014, 5, 234–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankrajang, T. State-community property-rights sharing in forests and its contributions to environmental outcomes: Evidence from Thailand’s community forestry. J. Dev. Econ. 2019, 138, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderlin, W.D. Poverty alleviation through community forestry in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam: An assessment of the potential. For. Policy Econ. 2006, 8, 386–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvig, A.; Wilding, M.; Thorogood, A.; Weiss, G. Social innovation in the Welsh Woodlands: Community based forestry as collective third-sector engagement. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 95, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, B.D.; Bigsby, H.; Macdonald, I. The relative distribution: An alternative approach to evaluate the impact of community level forestry organisations on households. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J.M. Community forestry engagement with market forces: A comparative perspective from Bhutan and Montana. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 58, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, Y.; Devkota, B.P. Farmers’responsibilization in payment for environmental services: Lessons from community forestry in Nepal. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryudi, A.; Devkota, R.R.; Schusser, C.; Yufanyi, C.; Salla, M.; Aurenhammer, H.; Rotchanaphatharawit, R.; Krott, M. Back to basics: Considerations in evaluating the outcomes of community forestry. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Huelsz, J.A.; Gerez Fernández, P.; López Binnqüist, C.; Guibrunet, L.; Ellis, E.A. Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Community Forest Management: Evolution and Limitations in Mexican Forest Law, Policy and Practice. Forests 2020, 11, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.M. Learning on Governance in Forest Ecosystems: Lessons from Recent Research. Int. J. Commons 2010, 4, 687–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, R.; Lawler, J. Community forestry research in Canada: A bibliometric perspective. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 59, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putraditama, A.; Kim, Y.-S.; Baral, H. Where to put community-based forestry?: Reconciling conservation and livelihood in Lampung, Indonesia. TreesFor. People 2021, 4, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebreegziabher, Z.; Mekonnen, A.; Gebremedhin, B.; Beyene, A.D. Determinants of success of community forestry: Empirical evidence from Ethiopia. World Dev. 2021, 138, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schusser, C.; Krott, M.; Movuh, M.C.Y.; Logmani, J.; Devkota, R.R.; Maryudi, A.; Salla, M. Comparing community forestry actors in Cameroon, Indonesia, Namibia, Nepal and Germany. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 68, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, E.; Ingram, V. Impacts of community forests on livelihoods in Cameroon: Lessons from two case studies. Int. For. Rev. 2011, 13, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitoe, A.; Guedes, B. Community Forestry Incentives and Challenges in Mozambique. Forests 2015, 6, 4558–4572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Impact of Collaborative Forest Management on Rural Livelihood: A Case Study of Maple Sap Collecting Households in South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanzel, J.; Krott, M.; Schusser, C. Power alliances for biodiversity—Results of an international study on community forestry. Land Use Policy 2020, 97, 102963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicators | Unit | Counties | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longsheng | Luocheng | Dushan | Libo | ||

| Area | km2 | 2538 | 2651 | 2442.2 | 2431.8 |

| Population | Persons | 1.72 × 105 | 3.86 × 105 | 3.58 × 105 | 1.8 × 105 |

| Forest coverage rate | % | 81.76 | 70.28 | 61.84 | 71.04 |

| Poor population | Persons | 414 | 6509 | 4202 | 352 |

| Incidence of poverty | % | 0.26 | 2.21 | 1.36 | 1.53 |

| Rural per capita income | CNY/year | 1.28 × 104 | 8.9 × 103 | 1.18 × 104 | 1.14 × 104 |

| Indicators | Unit | Counties | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longsheng | Luocheng | Dushan | Libo | ||

| Accumulated employees | Persons | 3965 | 4621 | 3054 | 3500 |

| Accumulated dismissals | Persons | 813 | 413 | 104 | 350 |

| On-duty personnel | Persons | 3152 | 4208 | 2950 | 3150 |

| Per capita protection area | Hectare | 61.27 | 42.6 | 40.4 | 53.47 |

| Cumulative capital investment | CNY | 7.7 × 107 | 1.14 × 108 | 8.85 × 107 | 9.05 × 107 |

| Characteristic | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | below 31 years old | 5 | 0.03 |

| 31–40 years old | 39 | 0.20 | |

| 41–50 years old | 82 | 0.42 | |

| 51–60 years old | 64 | 0.32 | |

| over 60 years old | 2 | 0.01 | |

| Gender | Male | 176 | 0.92 |

| Female | 16 | 0.08 | |

| Education | Not attending school | 8 | 0.04 |

| Primary (Grade 1–6) | 87 | 0.45 | |

| Middle (Grade 7–9) | 86 | 0.45 | |

| High (Grade 10–) | 11 | 0.06 | |

| Use of smartphone | Yes | 183 | 0.95 |

| No | 9 | 0.05 | |

| Use of WeChat | Yes | 178 | 0.93 |

| No | 14 | 0.07 |

| Indicators | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Average household income before employment | CNY/Year | 13,693.28 |

| Average household income in 2019 | CNY/Year | 26,220.31 |

| Change in household income | CNY/Year | 12,527.03 |

| Average remuneration of EFRs | CNY/Year | 9507.41 |

| The ratio of remuneration to household income in 2019 | % | 36.26 |

| The ratio of remuneration to income change | % | 75.9 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhao, R. The Effectiveness of the Ecological Forest Rangers Policy in Southwest China. Forests 2021, 12, 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12060746

Wang Y, Wang D, Zhao R. The Effectiveness of the Ecological Forest Rangers Policy in Southwest China. Forests. 2021; 12(6):746. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12060746

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yifan, Dengju Wang, and Rong Zhao. 2021. "The Effectiveness of the Ecological Forest Rangers Policy in Southwest China" Forests 12, no. 6: 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12060746

APA StyleWang, Y., Wang, D., & Zhao, R. (2021). The Effectiveness of the Ecological Forest Rangers Policy in Southwest China. Forests, 12(6), 746. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12060746