The Contribution of Non-Wood Forest Products to Rural Livelihoods in Tunisia: The Case of Aleppo Pine

Abstract

:1. Introduction

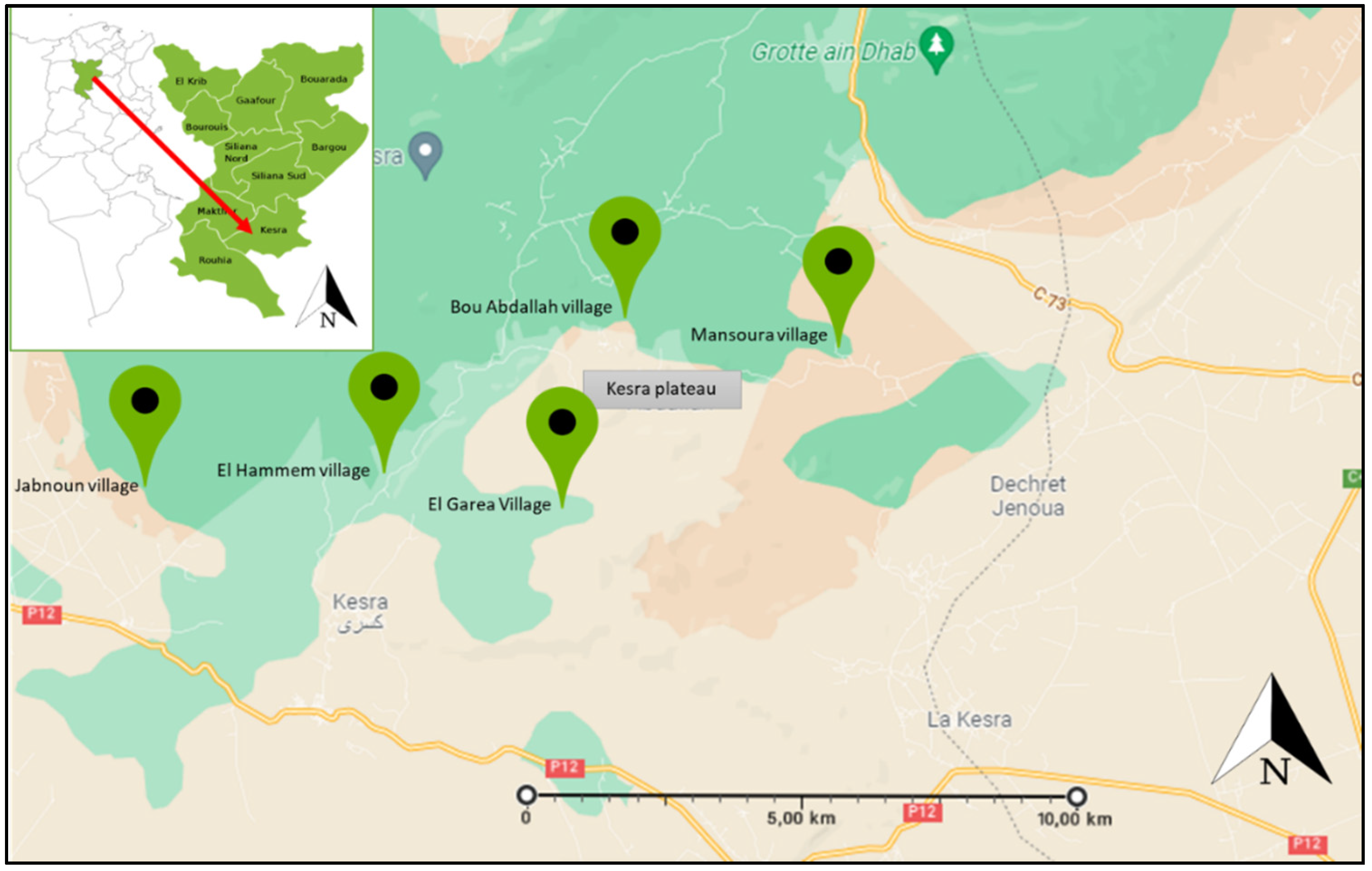

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shackleton, S.; Shackleton, C.; Shanley, P. Non-Timber Forest Products in the Global Context; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, G.; Emery, M.R.; Corradini, G.; Živojinović, I. New values of non-wood forest products. Forests 2020, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Odebode, S.O. Contributions of Selected Non-Timber Forest Products to Household Food Security in Nigeria. 2005. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/xii/0182-a1.htm#fnB2 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Ojea, E.; Loureiro, M.L.; Alló, M.; Barrio, M. Ecosystem services and REDD: Estimating the benefits of non-carbon services in worldwide forests. World Dev. 2016, 78, 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ros-Tonen, M.A.; Wiersum, K.F. The scope for improving rural livelihoods through non-timber forest products: An evolving research agenda. For. Trees Livelihoods 2005, 15, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurer, M.; Gritten, D.; Than, M.M. Community forestry for livelihoods: Benefiting from Myanmar’s mangroves. Forests 2018, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nepstad, D.C.; Schwartzman, S. Non-Timber Products from Tropical Forests. Evaluation of a Conservation and Development Strategy; New York Botanical Garden: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Panayotou, T.; Ashton, P. Not by Timber Alone: Economics and Ecology for Sustaining Tropical Forests; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez de Arano, I.; Maltoni, S.; Picardo, A.; Mutke, S. Non-Wood Forest Products for People, Nature and the Green Economy. Recommendations for Policy Priorities in Europe. A White Paper Based on Lessons Learned from around the Mediterranean; EFI and FAO: Barcelona, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton, S.; Campbell, B.; Lotz-Sistitka, H.; Shackleton, C. Links between the local trade in natural products, livelihoods and poverty alleviation in a semi-arid region of South Africa. World Dev. 2007, 36, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soe, K.T.; Yeo-Chang, Y. Livelihood dependency on non-timber forest products: Implications for REDD+. Forests 2019, 10, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Direction Générale des Forêts en Tunisie (DGF). Inventaire des Forêts par Télédétection, Final Report: Résultats du Deuxième Inventaire Forestier et Pastoral National (Tunisie-2010); Ministère de l’Agriculture de Tunisie: Tunis, Tunisia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zaibet, L. Potentials of Non-Wood Forest Products for Value Chain Development, Value Addition and Development of NWFP-Based Rural Microenterprises: Tunisia; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Regional Office for the Near East and North Africa: Tunis, Tunisia, 2016; p. 69. ISBN 978-92-5-109531-7. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i6507e/i6507e.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2021).

- Quezel, P. Taxonomy and biogeography of Mediterranean pines (Pinus halepensis and P. brutia). In Ecology, Biogeography and Management of Pinus halepensis and P. brutia Forest Ecosystems in the Mediterranean Basin; Ne’eman, G., Trabaud, L., Eds.; Backhuys Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jaouadi, W.; Mechergui, K.; Khouja, M.; Khouja, M.L. Potential of Aleppo pine production in northeastern Tunisia: Socioeconomic value and cultural importance. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 78, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly-Hassen, H.; Ben Mansoura, A. Tunisia. In Valuing Mediterranean Forests: Towards Total Economic Value; Merlo, M., Croitoru, L., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK; Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 105–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bladé, C.; Vallejo, V.R. Seed mass effects on performance of Pinus halepensis Mill. Seedlings sown after fire. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 2362–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, D.; De las Heras, J.; López-Serrano, F.R.; Leone, V. Optimal intensity and age of management in young Aleppo pine stands for post-fire resilience. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 3270–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh-Rouhou, S.; Hentati, B.; Besbes, S.; Blecker, C.; Deroanne, C.; Attia, H. Chemical composition and lipid fraction characteristics of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) seeds cultivated in Tunisia. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2006, 12, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sghaier, T.; Ammari, Y. Croissance et production du pin d’Alep (Pinus halepensis Mill.) en Tunisie. Ecol. Mediterr. 2012, 38, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaouadi, W.; Naghmouchi, S.; Alsubeie, M. Should the silviculture of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill.) stands in northern Africa be oriented towards wood or seed and cone production? Diagnosis and current potentiality. IForest 2019, 12, 297–305. [Google Scholar]

- Vedeld, P.; Angelsen, A.; Sjaastad, E. Counting on the Environment: Forest Incomes and the Rural Poor; Paper #98; The World Bank Environment Department: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Cashore, B.; Hardin, R.; Shepherd, G.; Benson, C.; Miller, D. Economic Contributions of Forests, Background Paper Prepared for the United Nations Forum on Forests; 2013; Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.269.2378&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Mujawamariya, G.; Karimov, A.A. Importance of socioeconomic factors in the collection of NTFPs: The case of gum arabic in Kenya. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 42, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, W.H. Econometric Analysis, 4th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 811–816. [Google Scholar]

- Suleiman, M.S.; Wasonga, V.O.; Mbau, J.S.; Suleiman, A.; Elhadi, Y.A. Non-timber forest products and their contribution to households income around Falgore Game Reserve in Kano, Nigeria. Ecol. Process. 2017, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jimoh, S.O.; Azeez, I.O. Prospects of community participation in the management of shasha forest reserve, Osun State, Nigeria. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of Forestry Association of Nigeria. Forestry and Challenges of Sustainable Livelihood, Akure, Nigeria, 4–8 November 2002; Abu, J.E., Oni, P.I., Popoola, L., Eds.; pp. 208–216. [Google Scholar]

- Daneji, M.I.; Suleiman, M.S. Accessibility and utilization of agricultural information among farmers in Wudil Local Government Area, Kano State. In Proceedings of the 36th Annual Conference of the Nigerian Society for Animal Production (NSAP), Abuja, Nigeria, 13–16 March 2011; pp. 652–654. [Google Scholar]

- Masozera, M.K.; Alavalapati, J.R.R. Forest dependency and its implications for protected areas management: A case study from the Nyungwe Forest Reserve, Rwanda. Scand. J. For. Res. 2004, 19, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Sundriyal, R.C. Utilization of non-timber forest products in humid tropics: Implications for management and livelihood. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 14, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, E. Food Security: Concepts and Measurement: Trade Reforms and Food Security: Conceptualizing the Linkages; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2002; pp. 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Feleke, S.T.; Kilmer, R.L.; Gladwin, C.H. Determinants of food security in Southern Ethiopia at the household level. Agric. Econ. 2005, 33, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, D.A.; Smith, L.C.; Rahman, T. Determinants of dietary quality: Evidence from Bangladesh. World Dev. 2011, 39, 2221–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carletto, C.; Zezza, A.; Banerjee, R. Towards better measurement of household food security: Harmonizing indicators and the role of household surveys. Glob. Food Secur. 2013, 2, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Measurement and Assessment of Food Deprivation and Undernutrition. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Symposium, Rome, Italy, 26–28 June 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Un Nouveau Modèle Economique: Développement, Justice, Liberté; Odile Jacob: Paris, France, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dercon, S.; Singh, A. From nutrition to aspirations and self-efficacy: Gender bias over time among children in four countries. World Dev. 2013, 45, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Headey, D.D.; Ecker, O. Improving the Measurement of Food Security; IFPRI Discussion Paper 01225; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Available online: http://ebrary.ifpri.org/cdm/ref/collection/p15738coll2/id/127261 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; De Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WFP, V.A.M. Food Consumption Analysis: Calculation and Use of the Food Consumption Score in Food Security Analysis; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, D.; Caldwell, R. The Coping Strategies Index: A Tool for Rapid Measurement of Household Food Security and the Impact of Food Aid Programs in Humanitarian Emergencies. Field Methods Manual-Second Edition; WFP: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- WFP—World Food Program (PAM). Manuel D’évaluation de la Sécurité Alimentaire en Situation D’urgence-Deuxième Edition 2009; Service de L’analyse de la Sécurité Alimentaire: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, G.; Ballard, T.; Dop, M.C. Guidelines for Measuring Household and Individual Dietary Diversity; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide (v.2); FHI 360/FANTA: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Fry, H.; Azad, K.; Kuddus, A.; Shaha, S.; Nahar, B.; Hossen, M.; Younes, L.; Costello, A.; Fottrell, E. Socio-economic determinants of household food security and women’s dietary diversity in rural Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2015, 33, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for Measurement of Food Access: Indicator Guide; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project; Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, D.; Vaitla, B.; Coates, J. How do indicators of household food insecurity measure up? An empirical comparison from Ethiopia. Food Policy 2014, 47, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, T.; Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Deitchler, M. Household Hunger Scale: Indicator Definition and Measurement Guide; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance II Project; FHI 360: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Abtew, A.A.; Pretzsch, J.; Secco, L.; Mohamod, T.E. Contribution of small-scale gum and resin commercialization to local livelihood and rural economic development in the drylands of Eastern Africa. Forests 2014, 5, 952–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heubach, K.; Wittig, R.; Nuppenau, E.A.; Hahn, K. The economic importance of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for livelihood maintenance of rural west African communities: A case study from northern Benin. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leßmeister, A.; Heubach, K.; Lykke, A.M.; Thiombiano, A.; Wittig, R.; Hahn, K. The contribution of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) to rural household revenues in two villages in south-eastern Burkina Faso. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 92, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aye, W.N.; Wen, Y.; Marin, K.; Thapa, S.; Tun, A.W. Contribution of mangrove forest to the livelihood of local communities in Ayeyarwaddy region, Myanmar. Forests 2019, 10, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belcher, B.; Schreckenberg, K. Commercialisation of non-timber forest products: A reality check. Dev. Policy Rev. 2007, 25, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coulibaly-Lingani, P.; Tigabu, M.; Savadogo, P.; Oden, P.C.; Ouadba, J.M. Determinants of access to forest products in southern Burkina Faso. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, B.P.; Richardson, R.B.; Tembo, G.; Mapemba, L. Rural household participation in markets for non-timber forest products in Zambia. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2014, 19, 487–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhraief, M.Z.; Dhehibi, B.; Daly Hassen, H.; Zlaoui, M.; Khatoui, C.; Jemni, S.; Rekik, M. Livelihoods strategies and household resilience to food insecurity: A case study from rural Tunisia. Sustainability 2019, 11, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Gevelt, T. The economic contribution of non-timber forest products to South Korean mountain villager livelihoods. For. Trees Livelihoods 2013, 22, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R.B. Ecosystem services and food security: Economic perspectives on environmental sustainability. Sustainability 2010, 2, 3520–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chukwuone, N.A.; Okeke, C.A. Can non-wood forest products be used in promoting household food security? Evidence from savannah and rain forest regions of Southern Nigeria. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Severity Category | Adaptive Coping Behavior | Severity Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | To reduce the overall amount of food in each meal | 1 |

| To reduce the number of meals | 1 | |

| To rely on less preferred and cheaper foods | 1 | |

| To be restricted to non-preferential foods | 1 | |

| Moderate | To borrow food | 2 |

| To buy food on credit | 2 | |

| To Harvest Forest products (APS) | 2 | |

| To practice early harvest | 2 | |

| Severe | To send household members to eat elsewhere | 3 |

| To send household members begging | 3 | |

| To reduce meals for adults | 3 | |

| To have illegal activities | 3 | |

| Very severe | To sell the house or plot or breeding animals | 4 |

| To remove children from school | 4 | |

| To send one of the family members looking for work elsewhere | 4 |

| No. | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 | In the past four weeks, did you worry that your household would not have enough food? |

| 2 | In the past four weeks, were you or any household member not able to eat the kinds of foods you preferred because of a lack of resources? |

| 3 | In the past four weeks, did you or any household member have to eat a limited variety of foods due to a lack of resources? |

| 4 | In the past four weeks, did you or any household member have to eat some foods that you really did not want to eat because of a lack of resources to obtain other types of food? |

| 5 | In the past four weeks, did you or any household member have to eat a smaller meal than you felt you needed because there was not enough food? |

| 6 | In the past four weeks, did you or any household member have to eat fewer meals in a day because there was not enough food? |

| 7 | In the past four weeks, was there ever no food to eat of any kind in your household because of lack of resources to get food? |

| 8 | In the past four weeks, did you or any household member go to sleep at night hungry because there was not enough food? |

| 9 | In the past four weeks, did you or any household member go a whole day and night without eating anything because there was not enough food? |

| Comparison of Household Income Source | Mean Differences | Standard Error | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural income | Off-farm income | −244.386 | 93,652 *** |

| Forest income | 83.536 | 36,047 ** | |

| Off-farm income | Agricultural income | 244.386 | 93,652 *** |

| Forest income | 327.922 | 93,652 *** | |

| Forest income | Agricultural income | −83.536 | 36,047 ** |

| Off-farm income | −327.922 | 93,652 *** | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | Marginal Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −3.280 | 0.817 | |

| Gender | −0.968 | 0.474 ** | −0.230 ** |

| Attending extension days | 1.732 | 0.849 ** | 0.348 *** |

| Agricultural training program | 1.208 | 0.600 ** | −0.273 ** |

| Household size | 0.212 | 0.083 *** | 0.053 *** |

| Farm size | −0.013 | 0.012 | −0.003 |

| Agricultural income share in total income | 1.140 | 0.764 | 0.283 |

| Distance to market | 0.288 | 0.053 *** | 0.072 *** |

| Livestock activity | −1.084 | 0.376 *** | −0.262 *** |

| χ2 test | 103.54 *** | ||

| Log-likelihood function | −121.511 | ||

| Pseudo-R2 test | 0.299 | ||

| Total observations N | 250 | ||

| Severity Category | Adaptive Coping Strategies | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mild (39.5%) | To reduce the overall amount of food in each meal | 40% |

| To reduce the number of meals | 29% | |

| To rely on less preferred and cheaper foods | 46% | |

| To be restricted to non-preferential foods | 44% | |

| Moderate (27.63%) | To borrow food | 42% |

| To buy food on credit | 62.5% | |

| To Harvest Forest products (APS) | 6% | |

| To practice early harvest | 0% | |

| Severe (12.38%) | To send household members to eat elsewhere | 6% |

| To send household members begging | 4% | |

| To reduce meals for adults | 37.5% | |

| To have illegal activities | 2% | |

| Very severe (2%) | To sell the house or plot or breeding animals | 4% |

| To remove children from school | 0% | |

| To send one of the family members looking for work elsewhere | 2% |

| Income Source | Food Security | Mild Food Insecurity | Moderate Food Insecurity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | Mean | Max | Min | |

| Total income (TND) | 10,797 | 43,820 | 2200 | 5587 | 12,845 | 1820 | 4507 | 10,420 | 2400 |

| Agricultural income (TND) | 3371 | 43,820 | 950 | 485 | 2520 | 260 | 295 | 1180 | 0 |

| Off-farm income (TND) | 6675 | 24,000 | 800 | 2894 | 9960 | 2160 | 2602 | 7000 | 808 |

| Forest income (TND) | 750 | 7000 | 1400 | 2208 | 5040 | 1440 | 1610 | 2240 | 1120 |

| Households collecting Aleppo pine | 39% | 43% | 18% | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taghouti, I.; Ouertani, E.; Guesmi, B. The Contribution of Non-Wood Forest Products to Rural Livelihoods in Tunisia: The Case of Aleppo Pine. Forests 2021, 12, 1793. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12121793

Taghouti I, Ouertani E, Guesmi B. The Contribution of Non-Wood Forest Products to Rural Livelihoods in Tunisia: The Case of Aleppo Pine. Forests. 2021; 12(12):1793. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12121793

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaghouti, Ibtissem, Emna Ouertani, and Bouali Guesmi. 2021. "The Contribution of Non-Wood Forest Products to Rural Livelihoods in Tunisia: The Case of Aleppo Pine" Forests 12, no. 12: 1793. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12121793

APA StyleTaghouti, I., Ouertani, E., & Guesmi, B. (2021). The Contribution of Non-Wood Forest Products to Rural Livelihoods in Tunisia: The Case of Aleppo Pine. Forests, 12(12), 1793. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12121793