Abstract

Agroforestry systems have been practiced for hundreds of years with multiple benefits both environmentally and economically in terms of productivity. Olive cultivation is widespread in the countries of the Mediterranean basin, including Greece. Agroforestry practices are common in olive groves, but little research has been conducted on the productivity of such systems, especially with medicinal–aromatic plants (MAPs) as understory crops. Natural populations of MAPs can be found in various ecosystems, while some of them are cultivated. The purpose of this research was to study the effects of fertilization and shading both on yield and chemical composition of essential oils derived from chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) and anise (Pimpinella anisum L.), grown in olive silvoarable systems. Fertilization and shading increased the plant height of chamomile and delayed the flowering. In addition, fertilization increased the concentration of α-bisabolol oxide A and (Z)–spiroether, and reduced the α-bisabolone oxide A and hamazulen. Shade also reduced α-bisabolone oxide A and hamazulen but increased the α-bisabolol oxide B. In the case of anise, fertilization increased plant height, decreased the concentration of limonene, and increased the concentration of E-anethole. Shading reduced plant height. Intercropping of olive trees with chamomile and anise yielded essential oils rich in the substances defined by the commercial specifications.

1. Introduction

The interest in silvoarable agroforestry systems has significantly increased in recent years because these systems are sustainable in terms of productivity and more environmentally friendly. They produce a variety of goods, thus improving the overall productivity of agricultural holdings, contribute to the reduction of rural migration by providing jobs, and bring profit and prosperity to rural and disadvantaged communities [1,2,3]. It is also well documented that silvoarable systems can reduce soil erosion and enrich the soil with organic matter [4], play a crucial role in carbon sequestration [5], improve microclimatic conditions and air quality, and enhance biodiversity [6].

Silvoarable agroforestry practices are applied to 358,000 hectares, accounting for merely 0.39% of the total agricultural land in Europe [7]. The most common silvoarable systems in the Mediterranean region are co-cultivation of broadleaf trees with cereals and co-cultivation of olive trees with vegetables and cereals [8]. In olive agroforestry systems, the trees are usually planted in lines, but they can also be in a scattered pattern, after thinning [9]. Common agroforestry systems are applied in olive groves or in other cultivated tree species such as oak (Quercus spp.), carob (Ceratonia siliqua L.), walnut (Juglanus regia L.), and almond (Prunus dulcis (Mill.) D.A.Webb) [9,10] with the cultivation of cereals, vegetables or legumes. Such systems can also combine grazing of the understory by small ruminants usually following the sowing of forage crops. Olive agroforestry systems produce a variety of products including olive oil and edible olives, firewood, timber, derivatives from co-cultivation, and grazing [10]. Agroforestry practices in olive groves used to be a traditional practice in the Mediterranean countries [9,11]; however, presently they are not as widespread in most countries. In Italy, only about 20,000 hectares of olive groves are co-cultivated or grazed, mainly in Umbria and Lazio; in Spain they are very rare, participating with very small numbers in the total land of olive groves, while in France they are completely demised [9]. In contrast, 124,300 hectares of the total area covered of olive groves estimated to 690,000 hectares [12] are co-cultivated or grazed in Greece [10].

From ancient times medicinal–aromatic plants (MAPs) have been widely used for their properties in cooking, medicine, cosmetics and elsewhere [13]. About 2500 species of MAPs are traded worldwide [14], with the biggest portion deriving from native vegetation [15]. Essential oils are widely used for their properties: antimicrobial, antiviral-antiepileptic, antifungal, antioxidant, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, sedative, expectorant, antispasmodic, anesthetic, insecticidal [16,17]. The collection of self-seeded material from nature led to the significant reduction of natural populations, their genetic degradation [18], and even their extinction [18,19]. Only a few species of MAPs are cultivated presently [18] and for the above reasons it is essential to expand the number of species cultivated.

Chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) is an annual species naturally distributed in the Mediterranean basin, but it also grows naturally in several areas of Europe, Asia, India, Algeria, Siberia, Australia, and the Americas [20,21]. It is cultivated in temperate countries such as Germany, Hungary, Russia, Kashmir, Lebanon, Argentina, Colombia, and elsewhere. It thrives in all types of soil acidity, but performs better in soils with high pH values. It can also be grown in clayey, shallow, and moist soils, while it grows better in soils rich in organic matter and temperatures from 7 to 26 °C [21]. The acreage yield of chamomile, both in dry plant material and in essential oil, but also its quality, is influenced by the climatic factors of the area [22]. Chamomile is categorized mainly into five chemotypes, based on its content of α-bisabolol, chamazulen, bisabolol oxide A and B, and bisabolone oxide in its essential oil. The components of the essential oil of each chamomile variety depend on the chemotype to which it belongs. The main ones are β-farnesene, germacrene D, bicyclogermacrene, α-farnesene, bisabolol oxide A, bisabolol oxide B, bisabolone oxide, α-bisabolol, chamazulene, and cis-trans-en-dicycloether [23,24,25,26,27]. For the marketing of chamomile essential oil there are some limits for certain substances, categorizing the essential oil into two categories—oil rich in bisabolol oxides (total of bisabolol oxides from 29% to 81% and chamazulen > 1%), and oil rich in bisabolol (bisabolol from 10% to 65%, chamazulen ≥ 1% and bisabolol with its oxides ≥ 20%) [25,28].

Anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) is an annual species mainly distributed in the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Asian countries [29], and it is cultivated in Spain, Mexico, France, Turkey, Lebanon, Russia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, India, China, Japan, Argentina and Greece. Anise consumption in European countries is higher than production, with Germany being the largest consumer [30]. Anise prefers open warm areas, with ideal growth temperatures from 18 to 25 °C. It is cultivated in plains and semi-mountainous areas and prefers medium composition, mainly calcareous, fertile and well-drained soils, with pH 6–8. The yields of anise in terms of seed and essential oil production are influenced mainly by climatic conditions [31], the period of sowing and harvesting, and cultivation treatments, such as irrigation and applied fertilization [30,32,33]. The categorization of anise derives from the percentage of the seed content in essential oil. The most important components of the oil are linalool with values ranging from 0.1% to 1.5%, estragol (0.5%–6.0%), α-terpineol (0.1%–1.5%), cis-anethole (less than 0.5%), trans-anethole (84%–93%) and anisaldehyde (0.1%–3.5%). Other components of the essential oil are pinene, limonene, p-methoxy acetophenone, and γ-himchalen (~2.0%). In the Greek varieties of anise, essential oil has a yield of up to 2.5% for whole seeds and up to 6% for fragmented seeds. It consists mainly of anethole (up to 95%), estragole (2.0%–3.0%), γ-himchalen (0.5%–2.5%), and p-anisaldehyde (0.3%–0.6%) [27].

Although MAPs have low requirements for nutrients, their productivity is affected by nutrients [34,35], so it is necessary that the absorbed nutrients are replenished on an annual basis, depending on the species, and especially during spring [19]. Plant growth seems to be affected using nitrogen (N) fertilizers [36]. The overall productivity of chamomile is affected by various macronutrients and micronutrients [37]. The productivity of chamomile in essential oil does not seem to be particularly affected by fertilization [38], with the phosphorous (P) fertilization to increase the essential oil content [39]. It has been observed that N fertilization rate of 75 kg/ha yields the largest amount of essential oil [36], but additional use of N fertilizer delays flowering, which negatively affects the production of essential oil [36,38]. Fertilization greatly affects the growth and productivity (seeds and essential oil) of anise [39]. More specifically, N [35] and P fertilization affect plant growth and the quantitative yield of anise essential oil [34]. Reduced N intake affects anise, as with various other MAPs, in terms of growth and productivity [40]. P affects metabolic processes, improves fertility, stimulates flowering, helps seed growth, and accelerates ripening [36].

The cultivation of MAPs in agroforestry silvoarable systems is possible [41], with high-quality products, equal to that of the native ones [18]. The cultivation of MAPs has multiple advantages over various other crops. MAPs offer higher yield per unit area and are less likely to be attacked by insects and diseases. For example, anise has been reported to act as an insecticide in the biological control of Bactrocera oleae (Rossi) [29]. MAPs can upgrade poor and unprofitable soils, yield long-term products, and ensure profit for farmers [42]. The most suitable MAPs for intercropping with trees are those that develop a deep root system and are shade-resistant [18], because of the competition that will be developed between the trees and the understory crop for sunlight and soil moisture. The impact of this competition can be negative or positive depending mainly on the combination of species selected [43]. It has been observed that some MAPs produce better yields when grown in agroforestry systems, such as species of the genus Mentha, Cymbopogon martini (Roxb.) W. Watson, Cymbopogon flexuosus (Nees ex Steud) Wats. and Piper longum L. in eucalyptus, poplar, and leuca (Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit) plantations [42]. Tree density affects the growth and chemical composition of MAPs [18], the total amount of biomass produced, and the composition and quality of their essential oils [18,19], but not to the same degree for all the MAP species [18]. Singh et al. [44] found that light shading provided by poplar trees did not affect the essential oil components of Cymbopogon winterianus Jowitt ex Bor and Cymbopogon martinii, but the oil of Mentha arvensis L. had lower amounts of menthone and higher amounts of menthol when grown under shading. Thus, the appropriate choice of the understory MAP species will have a significant impact on the success of the agroforestry system.

The purpose of this research was to study the effects of fertilization and shading on the productivity of anise and chamomile essential oils grown in olive silvoarable systems in terms of both yield and essential oil chemical composition. Our test hypothesis was that fertilization would benefit the plant growth, essential oil yield and chemical composition of anise and chamomile either alone or together with shading by olive trees. The research question of this study was: can anise and chamomile grow in olive agroforestry systems, and what are the effects of this co-cultivation on the productivity of those MAPs in terms of biomass and essential oil yields?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study area is in Tolofonas, Fokida region, central Greece (38°21′ N, 22°12′ E) at 10 m a.s.l. The climate of the area is classified as Mediterranean, with a mean air temperature of 19.0 °C and an annual rainfall of 392 mm. In 2018, the year the experiment was conducted, the mean annual precipitation was 483 mm, which was considerably higher than the annual average, and the mean temperature was 19.2 °C.

An olive grove with tree spacing of 8 × 8 m and an adjacent open field were selected in the study area to establish the experiment. The soil of the research area was analyzed (Soil Survey Laboratory “The Union” 2013) before the onset of the experiment. The soil texture in the olive grove is clay loam, while in the open field is silty clay (Table 1).

Table 1.

Soil characteristics of the experimental fields.

2.2. Experimental Design, Plant Material and Sampling Methods

The olive grove (shading) and the adjacent open field (control) served as shading treatments in the experiments. In the understory of the olive grove average light intensity was approximately 900 μE m−2 s−1 (75% of the total radiation), while light intensity in the open field was 1200 μE m−2 s−1 (100% of the total radiation). Light intensity was measured by a Licor quantum sensor (Li 190 SB). Chamomile and anise were cultivated in plots of 8 m2 (2 × 4 m) in each shading treatment. Eight plots per species were established in each shading treatment. The plots were separated by a bare earth strip of 2 m to avoid edge effects and to allow easy movement during the sampling periods. The minimum distance from the olive trees was 1 m.

The seeds of chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.) were of a B chemotype and diploid variety. They were sown in early January 2018 in boxes placed in a greenhouse. Then the seedlings were transplanted in the plots in late March 2018. The distances used for the transplanting were 33.3 cm between the rows and 20 cm between the plants. Anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) was directly shown in the plots at distances of 40 cm between the lines and 0.3~0.5 cm between the plants, in late March 2018. The seeds of anise were from a local cultivation on the island of Evia, central Greece.

Half of the plots with chamomile in both the olive grove and the open field were fertilized with triple hyperphosphate (0-46-0) with 34.90 kg ha−1, potassium sulfate (0-0-50) with 16.86 kg ha−1 and ammonia sulfate (21-0-0) with 23.80 kg ha−1. Half of the plots with anise in shaded and unshaded treatments were also fertilized with 39.88 kg ha−1 of triple hyperphosphate, 19.27 kg ha−1 of potassium sulfate and with 23.80 kg ha−1 of ammonia sulfate. The fertilizers were applied twice, in early and late May 2018. The main macronutrients of crop growth (N-P-K) were considered, while no special consideration was given to sulfur, which was assumed adequate in the fertilized plots due to the sulfate form of the applied fertilizers. Fertilization rates were defined based on the literature [16]. All plots were irrigated to field capacity once a week. Hand weeding was done when required.

Plant height was measured for both species prior to the plant material collection. The collection of chamomile flower heads was done manually in late June 2018, when the lingual flowers were in a horizontal position. The percentage of full bloom flower heads was estimated. Only those that were in full bloom condition (premium quality) were used for chemical analysis. The flower heads were dried naturally in a ventilated room on a cloth, shaded, with shredding, for a period of 7 days and then weighted. Anise was collected in mid-August 2018 manually. Only the ripe fruit were selected. They dried in an atrium, under shading, by shoveling in containers for a period of 2 days, stored in airtight containers, and then weighed. The plant material from both species was stored in airtight containers in cool and dry place away from light.

2.3. Isolation of Essential Oils

The dry stored plant material (see Section 2.2) was combined, per species and cultivation treatment, and grinded in a blender until fine particles formed. Then, each sample species that derived under different treatment was weighed, divided into three equal amounts, placed into a round bottom flask with deionized distilled water and submitted to hydrodistillation for 3 h using a Clevenger apparatus. The obtained essential oils, were dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filtrated and finally stored in labeled sterile screw capped bottle at −22 °C until analysis. Overall, four types of essential oils (according to the treatment applied) per species isolated and known as SnFCEO (shade without Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil), SFCEO (shade with Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil), nSnFCEO (without Shade without Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil), nSFCEO (without Shade with Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil), SnFAEO (shade without Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil), SFAEO (shade with Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil), nSnFAEO (without Shade without Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil), and nSFAEO (without Shade with Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil). Yield of the essential oils was determined on average of three replicates (per species and treatment) and expressed as mL of essential oil/100 g of dry material.

2.4. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) Analysis

Identification of essential oil was performed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) on a Varian CP-3800 GC, with a 1079 injector coupled with a 1200 L quadrupole mass spectrometer. One microliter of the essential oil (1:10 dilution) was used for the analysis. Separation of the analytes was performed with a TG-5MS capillary column (5% diphenyl/95% dimethyl polysiloxane) with dimensions 30-m length, 0.25-mm i.d., 0.25-μm film thickness (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Spitless mode was set for 1 min. The flow rate of the carrier gas helium was 1 mL min−1. The oven temperature was set at 60 °C and increased with a rate of 3 °C min−1 to the final temperature of 250 °C, with a total run of 63.33 min. Mass spectrometer was operated in Electron ionization mode (EI) with ion energy of −70 eV, filament current 50 μA and source temperature 200 °C. Data acquisition was performed in full scan (MS) with scanning range 40–300 amu. Tentative identification was achieved by comparing their elution order, the mass spectra with those from mass spectra libraries [45] (NIST 2005, Wiley 275) and literature data [45] (NIST-WebBook site). Retention indices (RI) of a series of n-alkane (C8–C20) were also used. Wherever possible, retention time and mass spectra were compared with commercial standards. The total ion chromatogram was processed by Varian MS Workstation software (version 6.9) based on the retention time and mass spectrum. Relative percentages (%) of the compounds were obtained electronically from the area percent data.

2.5. Data Analysis

The experimental design for each species consisted of two factors (two shading treatments and two fertilization levels). Within each of the two shading treatments (olive grove and open field), fertilization treatments were arranged in a randomized complete block design with four replications. The replicate measurements were not true replication (pseudoreplication), since only one contiguous area represented each shading treatment. Although this is a common case when working with existing field studies, it does introduce additional uncertainty into interpretation of the analysis. In this case, it is important to acknowledge that responses associated with either the main effect of shading, or interactions with shading, could be influenced by factors in addition to shading (such as soil variation) which are unmeasured but confounded with the unreplicated shade blocks. General linear models’ procedure (SPSS 18 for Windows) was used for two-way ANOVA. Prior to ANOVA all data sets were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov Smirnov test. The least significant difference (LSD) test [46] at p ≤ 0.05 was used to detect differences among means.

3. Results

3.1. Cultivation of Chamomile

Shading and fertilization application significantly affected the plant height of chamomile and the percentage concentrations of α-bisabolol oxide B, α-bisabolone oxide A, α-bisabolol oxide A, chamazulene and Z-spiroether (Table 2). Additionally, significant differences for full bloom flower heads percentage and dry flower head yield were recorded between fertilization treatments. The interaction of shading and fertilization was significant for essential oil yield as well as for all the main components of the oil besides chamazulene (Table 2).

Table 2.

Statistical significance of F ratios for growth parameters and essential oil main components of chamomile.

The plant height of chamomile across fertilization treatments was reduced in the olive grove (under shading). Shading did not affect the percentage of full bloom flower heads and their dry yield, as well as the essential oil yield (Table 3). The percentage concentrations of α-bisabolol oxide B, α-bisabolol oxide A, and Z-spiroether were significantly higher under shading, while those of α-bisabolone oxide A and chamazulene were lower (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of shading (across fertilization application treatments) on growth parameters and essential oil main components (mean ± SD) of chamomile.

The plant height and the dry flower head yield of chamomile increased under fertilization, while the essential oil yield was not affected by shading. The percentage of full bloom flower heads was reduced by fertilization. The concentrations of α-bisabolol oxide B, α-bisabolone oxide A, and Z-spiroether were significantly higher in the control treatment, while those of α-bisabolol oxide A and chamazulene were higher under fertilization (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of fertilization (across shading treatments) on growth parameters and essential oil main components (mean ± SD) of chamomile.

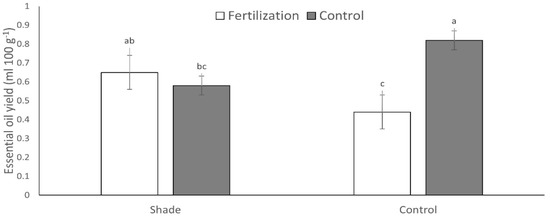

Fertilization significantly reduced the essential oil yield of chamomile in the open field, while no significant effect was observed under shade condition. The essential oil yield of chamomile was higher under shade for fertilized plants, and it was lower for the unfertilized ones (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Effects of shading and fertilizer application on the essential oil yield of chamomile. Columns followed by the same letter are not significantly different (p ≤ 0.05).

The essential oil main components of chamomile grown in the open field were not affected by fertilization, except for Z-spiroether, which decreased with fertilizer application. Fertilization of shaded plants increased the percentage concentrations of α-bisabolol oxide B, α-bisabolol A, oxide, and Z-spiroether, but reduced the concentration of α-bisabolone oxide A. A tendency for increased concentrations under shading was detected especially in the fertilized plots for all the essential oil main components of chamomile, apart from α-bisabolone oxide A, for which the opposite trend was observed (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effects of shading and fertilizer application on the essential oil major components (mean ± SD) of chamomile.

The identification rate of the components of the chamomile essential oil in all four combinations of treatments ranged from 97.10% to 98.10% with a total of 28 ingredients being identified. Specifically, the highest number of substances (28) was recorded for samples grown in fertilized plots without shading, while the lowest number (16) was recorded in plants grown under shading without fertilization application (Table A1).

3.2. Cultivation of Anise

Shading and fertilization application significantly affected only the plant height of anise (Table 6). Additionally, significant differences for the percentage concentrations of E-anethole and limonene were recorded between fertilization treatments. No significant interactions were observed between shading and fertilization treatments for all the measured parameters (Table 6).

Table 6.

Statistical significance of F ratios from the analysis of variance for growth parameters and essential oil main components of anise.

The plant height (across fertilization treatments) of anise was reduced in the olive grove (under shading). Shading did not affect dry seed and essential oil yield or the concentrations of E-anethole and limonene (Table 7).

Table 7.

Effects of shading (across fertilization application treatments) on growth parameters and essential oil main components (mean ± SD) of anise.

The plant height (across shading treatments) of anise increased under fertilization, while dry seed and essential oil yield did not differentiate. The percentage concentration of E-anethole increased with fertilization, while this of limonene was reduced (Table 8).

Table 8.

Effects of fertilization (across shading treatments) on growth parameters and essential oil main components (mean ± SD) of anise.

The identification rate of the components of the anise essential oil in all the combinations of treatments ranged from 98.9% to 99.9% with 17 ingredients being identified. Specifically, the highest number of substances (16) was recorded for samples grown under shade without fertilization, and the lowest (13) was recorded in plants grown under shading with fertilization application (Table A2).

4. Discussion

The effects of fertilization and shading on the production of essential oils in terms of both yield and chemical composition were not the same for anise and chamomile. There were significant effects of shading and fertilization interactions for essential oil yield and almost all the main components of the oil in chamomile. The effects of fertilization on oil yield and components depended on shading. Contrary to chamomile, there were no significant effects of shading and fertilization interactions for any of the studied characteristics. The major effects were verified for fertilization treatment, while the shade factor was significant only for height.

4.1. Chamomile

The height of chamomile plants increased with fertilizer application in the open field, while under shading the plants had lower height at harvest. The increased plant height with fertilizer application in chamomile plants could be attributed to the nitrogen fertilization applied in the form of ammonia, which has been reported to result in better plant growth in terms of height [36,47], while potassium and sulfur may have played a positive role through promoting photosynthesis and plant metabolism. On the other hand, the negative effect of shading on plant height is most likely related to reduced photosynthesis rates of plants [48]. Nevertheless, this point requires further clarification because interactions between shade and yields are possible in agroforestry systems due to differences in precipitation and soil nutrient status [49]. It is noteworthy that much higher heights of chamomile have been reported under fertilization in Iran [24,50]. This difference can be explained by the different climatic conditions and the different soil texture in the study areas. It has been documented that geographical and climatic differences affect the morphology of chamomile [51].

The percentage of the bloomed flower heads was significantly lower in the fertilized plots. This effect is probably associated with the excessive N uptake, which contributed to delayed flowering of plants [36,38]. Shading did not affect the opening of the flower heads of the plants, probably because of the wide olive tree spacing. Fertilizer application increased the dry matter productivity of flower heads, while shading did not have a significant effect. Previous studies have reported the positive effects of ammonia fertilization [21,50,52], vermicompost and zeolite application [53] on the flower head production of chamomile.

The production of essential oil was not affected by fertilization or by shading. However, the interaction of those treatments produced significant results. Plants in the fertilized plots grown under shade produced significantly higher amounts of essential oil than those grown in the open field. This finding can probably be attributed to the better development of the root system of the plants under shading due to the increased soil moisture [54,55], and therefore the greater capacity for nutrient binding, especially N [36] and P, from the soil to the flowers, which ultimately improved oil yield [37]. It has been reported that under shading conditions for the fertilized plants the percentage of essential oil yield was higher, as with ammonium fertilization enhanced the formation of essential oil cells [56], while in the absence of shading, the highest percentage was observed in non-fertilized plants. A recent study [57] suggested that the essential oil yield in lemon balm plants under partial shade was higher than that under full sunlight, probably because assimilates might have been directed to repair mechanisms necessary to support plant growth under high irradiance conditions.

The essential oil obtained from all the combinations of shading and fertilization meets the eligibility requirements defined by the European Pharmacopoeia [28]. Fertilization reduced the α-bisabolol oxide B percentage concentration, while shading increased it. The biosynthesis of this substance, as well as of the α-bisabolol oxide A, is controlled by gene interactions [56]. The percentages of these terpenes were expected to be increased until the final stage of flowering [53], but as excessive ammonia fertilization affects the duration of flowering, it is likely that it also negatively affected the biosynthesis of the components discussed. On the other hand, the increase in the concentration of α-bisabolol oxide B in plants grown under the olive tree shade is most likely explained by the balancing of the rhythms of the photosynthetic process, which were reduced due to the prolonged duration of flowering. According to a previous study in Iran, fertilization led to a slight increase of α-bisabolol oxide B [53], possibly because of the different fertilizer used and the differences in soil texture. The effects of fertilization were stronger under shading probably because of the competition between hydrocarbon terpenes and oxygenated terpenes, which tends to inversely relate the substances of one group with their concentration rates [56].

Fertilization and shading reduced the concentration of α-bisabolone oxide A. This reduction can be related to the delayed maturity of the flowers caused by ammonia fertilization [53] and the reduction of the photosynthetic activity due to shading. The effects of fertilization were stronger under shading. The concentration of α-bisabolone oxide A was generally higher than that reported in previous studies [23,24,50].

Shading and fertilizer application resulted in an increase of α-bisabolol oxide A concentration. This result contradicts previous studies, which reported that fertilization, and in particular ammonia, reduced the concentration of this substance in chamomile essential oil [52,58], but it is in accordance with the results of Salehi et al. [53], who reported a positive effect of various fertilizers in the α-bisabolol oxide A concentration. This increase was significant in the olive grove, but not in the open field. Plants grown under shading and fertilization develop an extensive and more active root system due to increased soil moisture and ammonia fertilization [53], which in turn result in better uptake of N and P [36], which play an important role in the biosynthesis of the substance [53]. In contrast, non-fertilized plants in the open field had a relative higher concentration of this substance, although not statistically significant. Nutrient deficiencies, high evaporation, and low soil moisture are quite stressful conditions for plants, and play an important role in the composition of the secondary metabolites [59].

Fertilization as well as shading reduced the percentage concentration of chamazulene in chamomile. Fertilization effects on this substance depend on fertilization type and quantity. Increased concentration of chamazulene with vermicompost, zeolite and ammonia fertilization has been recorded [52,53], while Emongor et al. [56] stated that excessive fertilization reduce it. Although N fertilization increases photosynthetic rates [53], this effect is weak under shading conditions and consequently the concentration of chamazulene in the essential oil remained low.

Fertilization significantly increased the percentage concentration of Z-spiroether, which is probably associated with the competition between hydrocarbons and oxygenated terpenes. The opposite relationship between the two groups of terpenes means that the concentrations of hydrocarbons increase as those of oxygenated ones decrease and vice versa [56]. Generally, it has been observed that N fertilization has a positive effect on the component percentages of Z-spiroether [56]. In contrast, shading reduced the concentration of this compound, albeit slightly, by reducing the photosynthetic capacity of plants, which significantly affects the production of secondary metabolites through the synthesis of primary metabolites [60].

Under shading conditions, the fertilized plants had higher concentration of Z-spiroether, as they had developed a more extensive root system [53] that enabled better nutrient uptake. The opposite trend was detected in non-shaded plots related to higher evaporation and the lower soil moisture [59].

4.2. Anise

The height of anise plants grown in fertilized plots was higher as a result of N and P application [34,35]. Shading had a negative impact on the plant height of anise, probably due to the reduced photosynthesis caused by the decreased intake of sunlight [48]. Similar findings regarding anise height grown under artificial shading have been reported by Ullah et al. [32].

Dry anise seed productivity was not affected by either the fertilizer application or shading. In contrast to the results of previous studies conducted in Turkey [34] and Spain [31] that reported higher seed yields of anise under fertilization, this was not confirmed in the current study. This result is probably related to the significantly lower amount of P and N applied to the experimental plots compared to those used in the other studies. The crucial role of tree density on the seed production of MAPs has been well documented [18,19]. The relatively low density of olive trees in the present study was the main reason for the stable seed production in the olive grove.

The essential oil productivity of anise was not affected by shading and fertilization. The yields of some MAPs do not appear to be affected by the uptake of sunlight, but are mainly affected by their growth cycle and nutrient yields [18], with the use of chemical fertilizers significantly affecting essential oil yields [39]. The use of limited amounts of P and N fertilization in the present study is the main reason behind the differentiated result regarding the yield of essential oil in the fertilized plots. It must be noted that the essential oil yield of anise found in this study ranged from 107.4 to 198.8 mL ha−1, and exceeded the average yields reported by Orav et al. [61] for various European countries, as well as those reported by Kara [31] in Turkey and by Ullah et al. [32] in Germany.

The essential oil obtained from all the combinations of shading and fertilization meets the eligibility requirements as defined by European Pharmacopoeia [28]. Both E-anethole and limonene percentage concentrations were not affected by shading, indicating that the shading produced by the olive trees had minimal effects on the essential oil components of anise. Similar to this result, Degani et al. [62] reported minimal effects of moderate shading on the essential oil composition of Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. The significant increase of the concentration of E-anethole after fertilization is related to the increase of available nutrients [63]. Anethole concentration in the present study was higher than the one reported by Ullah et al. [32] and similar to the findings of Fitsiou et al. [64]. In contrast, fertilization significantly reduced the concentration of limonene. The composition of secondary metabolites in MAPs depends mainly on the floral state and the stressful conditions [59]. Although generally, fertilization, particularly with N, increases the content of the components of the essential oils of MAPs, a similar reduction has been observed for limonene for fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.) [65], while Buntain and Chung [66] reported that the fennel oil components were not affected by N fertilization.

5. Conclusions

The use of both chamomile and anise as understory crops in olive agroforestry systems in the Mediterranean area is a very promising practice, supplementing the annual income of the farmers. The essential oil yield of both species was not affected by shading, and it was of high quality, meeting the criteria of commercial specifications. Fertilizer application seems to guarantee a high production in terms quantity and quality of the essential oils. Nevertheless, the productivity and the chemical composition of MAPs essential oils are influenced by various factors, such as soil and climatic conditions, cultivation practices and post-harvest handling and cultivated variety. Thus, further research is required to explore the effects of those factors on both species in olive silvoarable systems of various tree spacings. The study provides a useful first evaluation of the effects of fertilization and shading on the productivity of anise and chamomile grown in olive silvoarable systems in terms of both yield and essential oil chemical composition, for which limited data exist in the literature. However, conclusions on those effects, albeit promising, are restricted by only one year of data, which is a limitation of the current study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.P.K. and G.I.K.; methodology, G.I.K., A.C.K., C.A.D. and A.P.K.; software, G.I.K. and A.P.K.; validation, G.I.K.; formal analysis, G.I.K., E.A. and A.C.K.; investigation, G.I.K., A.C.K., E.A. and A.P.K.; data curation, G.I.K., E.A., A.C.K. and A.P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.I.K.; writing—review and editing, A.P.K.; visualization, A.P.K. and G.I.K.; supervision, A.P.K., A.C.K., E.A. and C.A.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Chamomile’s essential oils chemical composition under different treatments. SnFCEO: Shade without Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil, SFCEO: Shade with Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil, nSnFCEO: without Shade without Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil, nSFCEO: without Shade with Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil. Components are listed in order of elution from an TG-5MS column. Retention indices (RI), relative to n-alkanes, are listed alongside published values (Pub. RI from Adams 2007). Mean ± SD (n = 3).

Table A1.

Chamomile’s essential oils chemical composition under different treatments. SnFCEO: Shade without Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil, SFCEO: Shade with Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil, nSnFCEO: without Shade without Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil, nSFCEO: without Shade with Fertilizer Chamomile Essential Oil. Components are listed in order of elution from an TG-5MS column. Retention indices (RI), relative to n-alkanes, are listed alongside published values (Pub. RI from Adams 2007). Mean ± SD (n = 3).

| RI | Components | Relative Percentage Concentration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SnFCEO | SFCEO | nSnFCEO | nSFCEO | |||

| 1 | 999 | yomogi alcohol | - | - | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | 1058 | artemisia ketone | - | - | - | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| 3 | 1179 | naphthalene | - | - | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 4 | 1235 | (3Z)-hexenyl 3-methyl butanoate | - | - | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 5 | 1272 | 4,8-dimethyl-nona-3,8-dien-2-one | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 |

| 6 | 1284 | trans anethole | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 |

| 7 | 1336 | δ-elemene | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | 1356 | eugenol | - | - | - | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| 9 | 1391 | β-elemene | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 10 | 1447 | methyl naphthol | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| 11 | 1458 | (E)-β-farnesene | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 7.6 ± 1.2 |

| 12 | 1479 | γ-muurolene | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| 13 | 1495 | bicyclogermacrene | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| 14 | 1507 | (Ε, Ε)-α-farnesene | - | - | - | 0.3 ± 0.2 |

| 15 | 1522 | δ-cadinene | - | - | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 16 | 1565 | (Ε)-nerolidol | - | 0.7 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| 17 | 1578 | spathulenol | 3.8 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.3 | 4.4 ± 0.6 |

| 18 | 1591 | salvial-4(14)-en-1-one | - | - | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 19 | 1630 | nerolidol oxide | - | - | - | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

| 20 | 1639 | epi-α-cadinol | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| 21 | 1660 | α-bisabolol oxide B | 37.1 ± 0.8 | 30.9 ± 0.9 | 29.9 ± 1.6 | 29.9 ± 1.1 |

| 22 | 1686 | α-bisabοlone oxide A | 15.9 ± 0.8 | 11.2 ± 1.2 | 17.3 ± 0.3 | 17.3 ± 0.6 |

| 23 | 1730 | chamazulene | 11.9 ± 0.8 | 8.6 ± 0.8 | 14,0 ± 0.7 | 9.2 ± 0.4 |

| 24 | 1751 | α-bisabolol oxide A | 16.0 ± 0.9 | 22.3 ± 1.4 | 18.2 ± 0.6 | 16.6 ± 0.7 |

| 25 | 1773 | dimethyl biphenyl | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 26 | 1880 | (Z)-spiroether | 8.3 ± 0.9 | 15.3 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 0.3 |

| 27 | 1891 | (E)-spiroether | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| 28 | 1948 | 1,4-dimethyl-7-(1-methylethyl)-azulene-2-ol | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| Total | 97.5 | 98.1 | 97.1 | 98.1 | ||

Table A2.

Anise’s essential oils chemical composition under different treatments. % (mean ± SD). SnFAEO: Shade without Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil, SFAEO: Shade with Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil, nSnFAEO: without Shade without Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil, nSFAEO: without Shade with Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil. Components are listed in order of elution from an TG-5MS column. Retention indices (RI), relative to n-alkanes, are listed alongside published values (Pub. RI from Adams 2007). Mean ± SD (n = 3).

Table A2.

Anise’s essential oils chemical composition under different treatments. % (mean ± SD). SnFAEO: Shade without Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil, SFAEO: Shade with Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil, nSnFAEO: without Shade without Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil, nSFAEO: without Shade with Fertilizer Anise Essential Oil. Components are listed in order of elution from an TG-5MS column. Retention indices (RI), relative to n-alkanes, are listed alongside published values (Pub. RI from Adams 2007). Mean ± SD (n = 3).

| RI | Components | Relative Percentage Concentration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SnFAEO | SFAEO | nSnFAEO | nSFAEO | |||

| 1 | 932 | α-pinene | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 2 | 971 | sabinene | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 3 | 990 | myrcene | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| 4 | 1004 | α-phelladrene | 0.1 ± 0.0 | - | 0.1 ± 0.0 | - |

| 5 | 1022 | p-cymene | 0.2 ± 0.1 | - | - | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| 6 | 1029 | limonene | 6.5 ± 0.4 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 6.1 ± 0.2 | 4.7 ± 1.0 |

| 7 | 1036 | (Z)-β-ocimene | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 |

| 8 | 1057 | γ-terpinene | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| 9 | 1087 | fenchone | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | - |

| 10 | 1129 | allo-ocimene | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.3 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| 11 | 1199 | methyl chavicol | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.9 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 |

| 12 | 1253 | (Z)-anethole | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.2 + 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| 13 | 1288 | (E)-anethole | 87.2 ± 0.8 | 90.1 ± 0.6 | 87.6 ± 1.0 | 90.2 ± 0.5 |

| 14 | 1376 | α-copaene | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | - |

| 15 | 1458 | (E)-β-farnesene | 0.2 ± 0.1 | - | - | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| 16 | 1480 | germacrene D | - | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| 17 | 1522 | δ-cadinene | 0.2 ± 0.1 | - | - | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| Total | 99.8 | 99.9 | 99.9 | 99.8 | ||

References

- Current, D.; Lutz, E.; Scherr, S.J. The costs and benefits of agroforestry to farmers. World Bank Res. Obs. 1995, 1, 151–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leakey, R. Definition of agroforestry revisited. Agrofor. Today 1996, 8, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Pardini, A. Agroforestry Systems in Italy: Traditions towards Modern Management. In Agroforestry in Europe: Current Status and Future Prospects; Rigueiro-Rodríguez, A., McAdam, J., Mosquera-Losado, M., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media B.V.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo–Perez, A.; Rodriguez–Lizana, A.; Ordonez, R.; Giraldez, J.V. Soil loss and runoff reduction in olive–tree dry–farming with cover crops. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2013, 77, 2140–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Stefano, A.; Jacobson, M.G. Soil carbon sequestration in agroforestry systems: A meta-analysis. Agrofor. Syst. 2018, 92, 285–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerlich, K.S.; Graeff-Honninger, S.; Claupein, W. Agroforestry in Europe: A review of the disappearance of traditional systems and development of modern agroforestry practices, with emphasis on experiences in Germany. Agrofor. Syst. 2013, 87, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Herder, M.; Burgess, P.J.; Mosquera-Losada, M.R.; Herzog, F.; Hartel, T.; Upson, M.; Viholainen, I.; Rosati, A. Preliminary Stratification and Quantification of Agroforestry in Europe; Milestone Report 1.1 for EU FP7 AGFORWARD Research Project; 2015; Available online: https://www.agforward.eu/preliminary-stratification-and-quantification-of-agroforestry-in-europe.html (accessed on 28 October 2021).

- Den Herder, M.; Moreno, G.; Mosquera-Losada, R.M.; Palma, J.H.N.; Sidiropoulou, A.; Santiago Freijanes, J.J.; Crous-Duran, J.; Paulo, J.A.; Tomé, M.; Pantera, A.; et al. Current extent and stratification of agroforestry in the European Union. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 241, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eichhorn, M.P.; Paris, P.; Herzog, F.; Incoll, L.D.; Liagre, F.; Mantzanas, K.; Mayus, M.; Moreno, G.; Papanastasis, V.P.; Pilbeam, D.J.; et al. Silvoarable systems in europe past, present and future prospects. Agrofor. Syst. 2006, 67, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantzanas, K.; Pantera, A.; Koutsoulis, D.; Papadopoulos, A.; Kapsalis, D.; Ispikoudis, S.; Fotiadis, G.; Sidiropoulou, A.; Papanastasis, V.P. Intercrop of olive trees with cereals and legumes in Chalkidiki, Northern Greece. Agrofor. Syst. 2021, 95, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelle, M.A.; Gold, M.A. Agroforestry Systems for Temperate Climates: Lessons from Roman Italy. For. Conserv. Hist. 1994, 38, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EUROSTAT. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20190301-1 (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Bogers, R.J.; Craker, L.E.; Lange, D. Medicinal and Aromatic Plants; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schippmann, U.; Leaman, D.J.; Cunnningham, A.B. Impact of cultivation and gathering of medicinal plants on biodiversity: Global trends and issues. In Biodiversity and the Ecosystem Approach in Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Proceedings of the Ninth Regular Session of the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, Rome, Italy, 14–18 October 2002; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2002; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Bown, D. New Encyclopedia of Herbs and Their Uses; Dorling Kindersley Ltd.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dordas, C. Aromatic and Medicinal Plants; Modern Education: Thessaloniki, Greece, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I. An overview of the biological effects of some Mediterranean essential oils on human health. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 9268468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.R.; Palada, M.C.; Becker, B.N. Medicinal and aromatic plants in agroforestry systems. Agrofor. Syst. 2004, 61, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Franco, R. Medicinal plants: Cultivation possibilities. In Agroforestry Systems as a Technique for Sustainable Territorial Management; Mosquera-Losada, M.R., Fernández-Lorenzo, J.L., Rigueiro-Rodríguez, A., Eds.; Unicopia Editions: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2011; pp. 353–363. [Google Scholar]

- Zeven, A.C.; Zhukovsky, P.M. Dictionary of Cultivated Plants and Their Centres of Diversity: Excluding Ornamentals, Forest Trees and Lower Plants; Pudoc: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, O.; Khanam, Z.; Misra, N.; Srivastava, M.K. Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.): An overview. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2011, 5, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Formisano, C.; Delfine, S.; Oliviero, F.; Tenore, G.C.; Rigano, D.; Senatore, F. Correlation among environmental factors, chemical composition andantioxidative properties of essential oil and extracts of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) collected in Molise (South-central Italy). Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 63, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashidhara, K.V.; Verma, R.S.; Ram, P. Essential oil composition of Matricaria recutita L. from the lower region of the Himalayas. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 274–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghalian, K.; Abdoshah, S.; Khalighi-Sigaroodi, F.; Paknejad, F. Physiological and phytochemical response to drought stress of German chamomile (Matricaria recutita L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2011, 49, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raal, A.; Orav, A.; Pussa, T.; Valner, C.; Malmiste, B.; Arak, E. Content of essential oil, terpenoids and polyphenols in commercial chamomile (Chamomilla recutita L. Rauschert) teas from different countries. Food Chem. 2012, 131, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, N.D.; Asghari, G.; Mostajeran, A.; Najafabadi, A.M. Evaluating the composition of Matricaria recutita L. flowers essential oil in hydroponic culture. J. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 3, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Katsiotis, S.T.; Chatzopoulou, P.S. Aromatic Medicinal Plants and Essential Oils, Production Processing, Conversion, Utilization, International Markets, Aromatherapy, Perfumery, 3rd ed.; Kiriakidis: Athens, Greece, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve, S.A. European Pharmacopoeia, 8th ed.; Council of Europe: Sainte-Ruffine, France, 2013; pp. 1148–1150, 1314–1315. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, R.; Lo Verde, G.; Sinacori, M.; Maggi, F.; Cappellacci, L.; Petrelli, R.; Vittori, S.; Morshedloo, M.R.; N’Guessan Bra Fofie, Y.; Benelli, G. Developing green insecticides to manage olive fruit flies? Ingestion toxicity of four essential oils in protein baits on Bactrocera oleae. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 143, 111884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H. Fruit Yield and Quality of Anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) in Relation to Agronomic and Environmental Factors. Ph.D. Thesis, Justus Liebig University, Giessen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kara, N. Yield, quality, and growing degree days of anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) under different agronomic practices. Turk. J. Agric. For. 2015, 39, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Mahmood, A.; Honermeier, B. Essential oil and composition of anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) with varying seed rates and row spacing. Pak. J. Bot. 2014, 46, 1859–1864. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, L.; Fernandes, C.P. Aniseed (Pimpinella anisum, Apiaceae) Oils. In Essential Oils in Food Preservation, Flavor and Safety; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid Ali, K. Effect of phosphorous fertilization on anise, coriander and sweet fennel plants growing under arid region conditions. Med. Aromat. Plant Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 6, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid Ali, K. Effect of nitrogen fertilization on morphological and biochemical traits of some Apiaceae crops under arid region conditions in Egypt. Nusantara Biosci. 2013, 5, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewska, J.; Woropaj-Janczak, M. German chamomile performance after stubble catch crops and response to nitrogen fertilization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, A.; Kozhuharova, K.; Zheljazkov, V.D.; Craker, L.E. Mineral nutrition of chamomile (Chamomilla recutita L.). Acta Hortic. 1999, 502, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa Junior, C.; Castellane, P.D.; Jorge Neto, J. Influence of organic and chemical fertilization on the yield of flowers, contents and composition of essential oil of (Chamomilla recutita (L.) Rauschert). Acta Hortic. 1999, 502, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aćimović, M.G. The influence of fertilization on yield of caraway, anise and coriander in organic agriculture. J. Agric. Sci. 2013, 58, 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Abd–Allah, A.M.; Adamand, S.M.; Abou-Hadid, A.F. Productivity of green cowpea in sandy soil as influenced by different organic manure rates and sources. Egypt. J. Hortic. 2001, 28, 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Laird, S.A.; Pierce, A.R. Strategies to improve commercial raw material sourcing. Results from the sustainable botanicals pilot project. Industry surveys, case studies and standards collection. Med. Plant Conserv. 2002, 8, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sujatha, S.; Bhat, R.; Kannan, C.; Balasimha, D. Impact of intercropping of medicinal and aromatic plants with organic farming approach on resource use efficiency in arecanut (Areca catechu L.) plantation in India. Ind. Crops Prod. 2011, 33, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palada, M.C.; Mitchell, J.M.; Becker, B.N.; Nair, P.K.R. The Integration of Medicinal Plants and Culinary Herbs in Agroforestry Systems for the Caribbean: A Study in the U.S. Virgin Islands. III World Congress on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Volume 2: Conservation, Cultivation and Sustainable Use of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants. Acta Hortic. 2005, 676, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, K.; Rajeswara Rao, B.R.; Rajput, D.K.; Bhattacharya, A.K.; Chauhan, H.S.; Mallavarapu, B.R.; Ramesh, S. Composition of essential oils of menthol mint (Mentha arvensis var. piperascens), citronella (Cymbopogon winterianus) and palmarosa (Cymbopogon martinii var. motia) grown in the open and partial shade of poplar (Populus deltoides) trees. J. Med. Aromat. Plant Sci. 2002, 24, 710–712. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R. Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gaschromatography/Mass Spectrometry, 4th ed.; Allured Business Media: Carol Stream, IL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, R.G.D.; Torrie, J.H. Principles and Procedures of Statistics. A Biometrical Approach, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Meawad, A.A.; Awad, A.E.; Afify, A. The combined effect of N–fertilization and some growth regulators on chamomile plants. Acta Hortic. 1984, 144, 123–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, M.U.E. Does enhanced Photosynthesis enhance growth? Lessons learned from CO2 enrichment studies. Plant Physiol. 2011, 155, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asare, R.; Asare, R.A.; Asante, W.A.; Markussen, B.O.; Ræbild, A. Influences of shading and fertilization on on-farm yields of cocoa in Ghana. Exp. Agric. 2017, 53, 416–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahmati, M.; Azizi, M.; Khayyat, M.H.; Nomati, H.; Asili, J. Yield and oil constituets of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) flowers depending on nitrogen application, plant density and climate conditions. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2011, 14, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solouki, M.; Mehdikhani, H.; Zeinali, H.; Emamjomeh, A.A. Study of genetic diversity in chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) based on morphological traits and molecular markers. Sci. Hortic. 2008, 117, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoulis, K.D.; Kamvoukou, C.A.; Gougoulias, N.; Wogiatzi, E. Matricaria chamomilla L. (German chamomile) flower yield and essential oil affected by irrigation and nitrogen fertilization. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2020, 32, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A.; Gholamhoseini, M.; Ataei, R.; Sefikon, F.; Ghalavand, A. Effects of Zeolite, Bio- and Organic fertilizers Application on German Chamomile Yield and Essential Oil Composition. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2018, 21, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, A.J. Influence of trees on savannah productivity: Test of shade, nutrients, and treegrass competition. Ecology 1994, 75, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardales, J.R., Jr.; Banoc, D.M.; Yamauchi, A.; Ijima, M.; Esquibel, C. The effect of soil moisture fluctuation on root development during the establishment phase of sweetpotato. Plant Prod. Sci. 2002, 3, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emongor, V.E.; Chweya, J.A.; Keya, S.O.; Munavi, R.M. Effect of nitrogen and phosphorus on the essential oil yield and quality of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) flowers. East Afr. Agric. For. J. 1990, 55, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.C.; Vieira, W.L.; Bertolli, S.C.; Pacheco, A.C. Photosynthetic behavior, growth and essential oil production of Melissa officinalis L. cultivated under colored shade nets. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2016, 76, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, O. Cultivation of Matricaria chamomilla. In Supplement to Cultivation and Utilization of Aromatic Plants; Handa, H.S., Kaul, M.K., Eds.; Jammu-Tawi: Regional Research Laboratory (CSIR): Jammu, India, 1997; pp. 241–253. [Google Scholar]

- Burducea, M.; Zheljazkov, V.D.; Dincheva, I.; Lobiuc, A.; Teliban, G.C.; Stoleru, V.; Zamfirache, M.M. Fertilization modifies the essential oil and physiology of basil varieties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 121, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernáth, J. Production ecology of secondary plant products. In Spices, and Medicinal Plants: Recent Advances in Botany, Herbs, Horticulture and Pharmacology; Craker, L.E., Simon, J.E., Eds.; Oryx Press: Phoenix, AZ, USA, 1986; Volume 1, pp. 185–234. [Google Scholar]

- Orav, A.; Raal, A.; Arak, E. Essential oil composition of Pimpinella anisum L. fruits from various European countries. Nat. Prod. Res. 2008, 22, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degani, A.V.; Dudai, N.; Bechar, A.; Vaknin, Y. Shade Effects on Leaf Production and Essential Oil Content and Composition of the Novel Herb Eucalyptus citriodora Hook. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants 2016, 19, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.K. Quality and quantity of Pimpinella anisum L. essential oil treated with macro and micronutrients under desert conditions. Int. Food Res. J. 2015, 22, 2396–2402. [Google Scholar]

- Fitsiou, E.; Mitropoulou, G.; Spyridopoulou, K.; Tiptiri-Kourpeti, A.; Vamvakias, M.; Bardouki, H.; Panayiotidis, M.; Galanis, A.; Kourkoutas, Y.; Chlichlia, K.; et al. Phytochemical profile and evaluation of the biological activities of essential oils derived from the Greek aromatic plant species Ocimum basilicum, Mentha spicata, Pimpinella anisum and Fortunella margarita. Molecules 2016, 21, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatzopoulou, P.S.; Koutsos, T.V.; Katsiotis, S.T. Study of nitrogen fertilization rate on fennel cultivars for essential oil yield and composition. J. Veg. Sci. 2006, 12, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buntain, M.; Chung, B. Effects of irrigation and nitrogen on the yield components of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill). Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1994, 34, 845–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).