How Can Local and Regional Knowledge Networks Contribute to Landscape Level Action for Tree Health?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Global Threats Require Holistic Responses

1.2. The Role of Knowledge Networks in Responding to Tree Health Issues

- ○

- whether LRKNs facilitate action based on evidence-based learning;

- ○

- the role of LRKNs in raising awareness and supporting social learning;

- ○

- how LRKNs encourage and support mitigation and adaptation to tree pests and diseases on a landscape level to build long-term resilience.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Networks: Encouraging and Supporting Mitigation and Adaptation Actions

“A benefit from this is that information is cascaded by members of the group to colleagues, and that outbreaks of quarantine pests and diseases […] in this region are often picked up and reported at an early stage potentially allowing more rapid management.”(Network 2, interviewee 8)

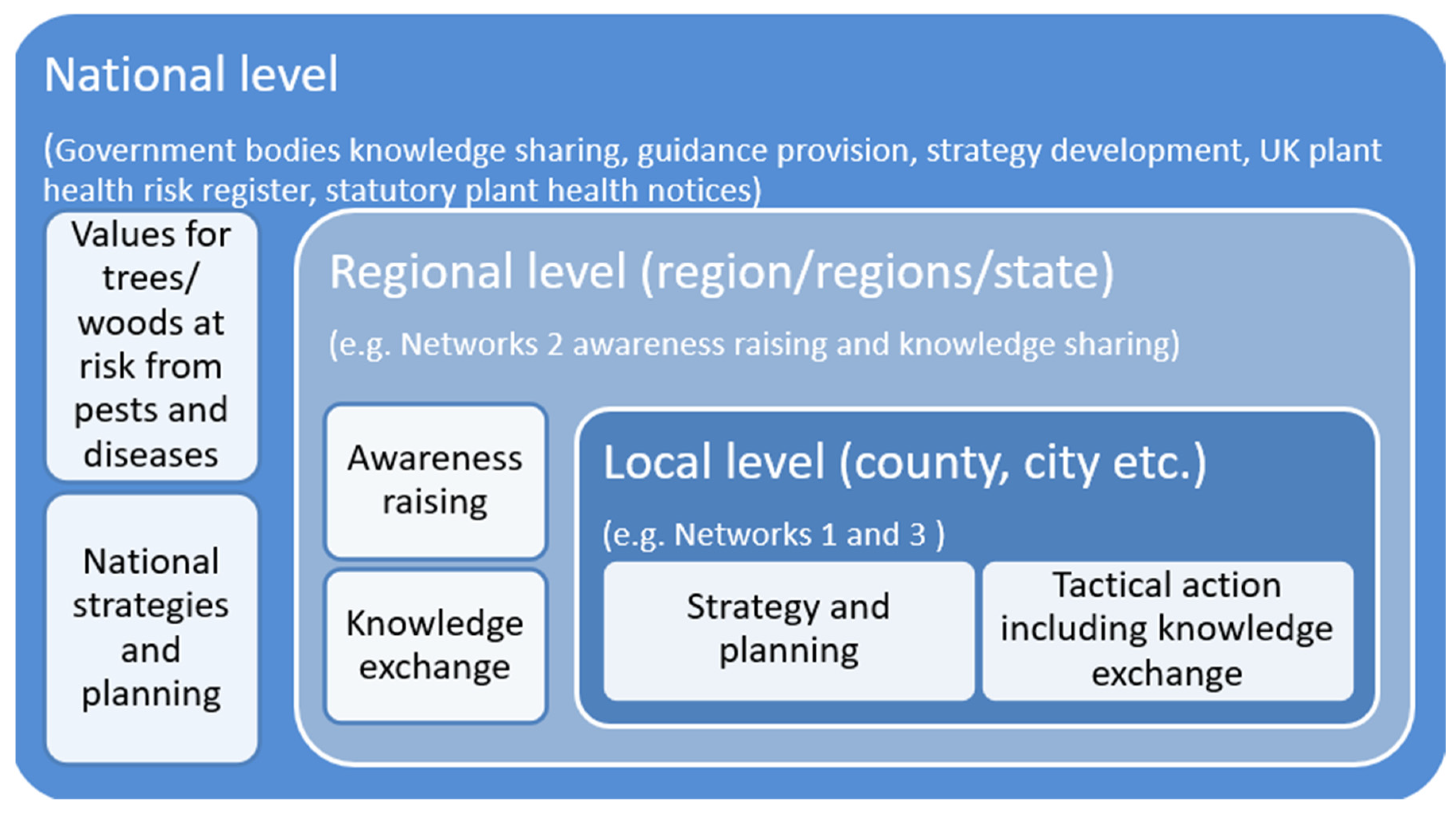

3.2. Networks: Operating at Multiple Levels across the Landscape

“So it was kind of bringing all those people together to have those conversations and then bringing experts in […]. So we had meetings and then the attendees had larger meetings, or […] larger events where more people would come as well. So, it was building a network locally and then trying to raise awareness more broadly with landowners and the wider sector.”(Network 2 interviewee 11)

3.3. Networks: Evidence-Based Knowledge Exchange and Social Learning

“So it’s learning from other people about how they’ve done it and then putting that into place. So hopefully it won’t get here but if it does, I’m hoping we’ve got a half decent chance of getting it quickly enough.”(Network 3 Interviewee 7a)

“There’s a big social aspect as well to the [network] that probably isn’t really referenced very much but there’s a Christmas drink, there’s a summer drink and there’s a sort of trivial social but there’s also quite an important… people sit down and have a chat about their work and issues. So that’s actually a very important side to it and there’s lots of information exchange on that slightly more informal basis […] They are really important.”(Network 3 interviewee 15)

“I think being presented with information in a factual way led people to react to the arrival of pest diseases in a positive way […] and have a high level of compliance in dealing with infected [stands] in the [region] and as it’s predominantly privately owned woodland that’s affected most, it’s hats off to them for dealing with something that has an extra financial implication for them, but they understand that if they do something that may mitigate the impact on the surrounding [stands].”(Network 2 interviewee 8)

3.4. Networks: Improving Social Captial to Support and Enable Action

“Yes and building relationships is the critical bit as when something happens you are ready, …they swung straight into action because they trusted each other. You have to have a shared mission and a shared objective and shared thought processes to help you deliver the end point.”(Assisted in developing network 1 but not part of it, interviewee 13)

“There is an element […] that is advantageous if you are part of the herd, in that you are not the sole beast out there advocating something that everybody else is against. So, herd immunity gives you that cover and that is important. If everybody has agreed, then it is stronger to articulate this is not just our X organisation’s view, this is our collective view.”(Network 1 interviewee 13)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marzano, M.; Urquhart, J. Understanding tree health under increasing climate and trade challenges: Social system considerations. Forests 2020, 11, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnakoski, R.; Kasanen, R.; Dounavi, A.; Forbes, K.M. Editorial: Forest Health Under Climate Change: Effects on Tree Resilience, and Pest and Pathogen Dynamics. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spence, N.; Hill, L.; Morris, J. How the global threat of pests and diseases impacts plants, people, and the planet. Plants People Planet 2020, 2, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, C.; Urquhart, J. Tree disease and pest epidemics in the Anthropocene: A review of the drivers, impacts and policy responses in the UK. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 79, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsfield, T.D.; Bentz, B.J.; Faccoli, M.; Jactel, H.; Brockerhoff, E.G. Forest health in a changing world: Effects of globalization and climate change on forest insect and pathogen impacts. Forestry 2016, 89, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainhouse, D.; Inward, D.J.G. The Influence of Climate Change on Forest Insect Pests in Britain. Fcrn021 2016, 1–10. Available online: https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/documents/6975/FCRN021.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Potter, C.; Harwood, T.; Knight, J.; Tomlinson, I. Learning from history, predicting the future: The UK Dutch elm disease outbreak in relation to contemporary tree disease threats. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 1966–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hubbes, M. The American elm and Dutch elm disease. For. Chron. 1999, 75, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anagnostakis, S.L. The effect of multiple importations of pests and pathogens on a native tree. Biol. Invasions 2001, 3, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Teixeira, K.J.; Herrmann, V.; Cass, W.B.; Williams, A.B.; Paull, S.J.; Gonzalez-Akre, E.B.; Helcoski, R.; Tepley, A.J.; Bourg, N.A.; Cosma, C.T.; et al. Long-Term Impacts of Invasive Insects and Pathogens on Composition, Biomass, and Diversity of Forests in Virginia’s Blue Ridge Mountains. Ecosystems 2020, 24, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, L.; Jones, G.; Atkinson, N.; Hector, A.; Hemery, G.; Brown, N. The £15 billion cost of ash dieback in Britain. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, R315–R316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, H.; Doick, K.; Handley, P.; O’Brien, L.; Wilson, J. Delivery of Ecosystem Services by Urban Forests; Forestry Commission: Farnham, UK, 2017; Volume 25, Available online: https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20173066323 (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Tran, T.A.; Rodela, R. Integrating farmers’ adaptive knowledge into flood management and adaptation policies in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta: A social learning perspective. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 55, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amundsen, H.; Berglund, F.; Westskog, H. Overcoming Barriers to Climate Change Adaptation—A Question of Multilevel Governance? Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2010, 28, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, J.S.; Peterson, D.L.; Millar, C.I.; O’Halloran, K.A. U.S. National Forests adapt to climate change through Science-Management partnerships. Clim. Chang. 2012, 110, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gregorio, M.; Fatorelli, L.; Paavola, J.; Locatelli, B.; Pramova, E.; Nurrochmat, D.R.; May, P.H.; Brockhaus, M.; Sari, I.M.; Kusumadewi, S.D. Multi-level governance and power in climate change policy networks. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 54, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, K.; Butler, W.H.; Sipe, N.; Chapin, T.; Murley, J. Voluntary Collaboration for Adaptive Governance: The Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2016, 36, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, E.M.; Nieuwenhuis, M.; Başkent, E.Z.; Biber, P.; Black, K.; Borges, J.G.; Bugalho, M.N.; Corradini, G.; Corrigan, E.; Eriksson, L.O.; et al. Forest decision support systems for the analysis of ecosystem services provisioning at the landscape scale under global climate and market change scenarios. Eur. J. For. Res. 2019, 138, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgman, M.A. Risks and Decisions for Conservation and Environmental Management; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Klapwijk, M.J.; Boberg, J.; Bergh, J.; Bishop, K.; Björkman, C.; Ellison, D.; Felton, A.; Lidskog, R.; Lundmark, T.; Keskitalo, E.C.H.; et al. Capturing complexity: Forests, decision-making and climate change mitigation action. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 52, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crona, B.I.; Parker, J.N. Learning in support of governance: Theories, methods, and a framework to assess how bridging organizations contribute to adaptive resource governance. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, L.; Lemos, M.C. Creating usable science: Opportunities and constraints for climate knowledge use and their implications for science policy. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichselgartner, J.; Arheimer, B. Evolving climate services into knowledge-action systems. Weather Clim. Soc. 2019, 11, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lawrence, A.; Gillett, S. Human Dimensions of Adaptive Forest Management and Climate Change: A Review of International Experience; Forestry Commission: Edinburgh, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Secco, L.; Pisani, E. Exploring the interlinkages between governance and social capital: A dynamic model for forestry. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 65, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defra. Protecting Plant Health. A Plant Biosecurity Strategy for Great Britain; Defra: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Defra. Tree Health Resilience Strategy. Building the Resilience of Our Trees, Woods and Forests to Pests and Diseases; Defra: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Forestry Commission. Forestry Statistics 2020; Forestry Commission: Edinburgh, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Marzano, M.; Dandy, N.; Papazova-Anakieva, I.; Avtzis, D.; Connolly, T.; Eschen, R.; Glavendekić, M.; Hurley, B.; Lindelöw, Å.; Matošević, D.; et al. Assessing awareness of tree pests and pathogens amongst tree professionals: A pan-European perspective. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 70, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marzano, M.; Allen, W.; Haight, R.G.; Holmes, T.P.; Keskitalo, E.C.H.; Langer, E.R.L.; Shadbolt, M.; Urquhart, J.; Dandy, N. The role of the social sciences and economics in understanding and informing tree biosecurity policy and planning: A global summary and synthesis. Biol. Invasions 2017, 19, 3317–3332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gov.uk. Tree Health Pilot Scheme. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/tree-health-pilot-scheme (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- OECD. Successful Partnerships: A Guide; OECD: Vienna, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, B.; Sankar, M.; Rogers, P. Evaluation of the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy 2000–2004: Networks and Partnerships (Issues Paper); RMIT University: Canberra, Australia, 2004; Available online: https://www.betterevaluation.org/sites/default/files/Evaluation%20of%20the%20Stronger%20Families%20and%20Communities%20Strategy.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Evans, C.H. Bowling alone: Implications for academic medicine. Acad. Med. 1997, 72, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.; Lee, C.A. Lessons learned from a decade of sudden oak death in California: Evaluating local management. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hemingway, R.; Gunawan, O. The Natural Hazards Partnership: A public-sector collaboration across the UK for natural hazard disaster risk reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 499–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defra. Review of Partnership Approaches for Farming and the Environment Policy Delivery; Defra: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rogge, N.; Theesfeld, I.; Strassner, C. The potential of social learning in community gardens and the impact of community heterogeneity. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2020, 24, 100351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibet, S.; Nyangito, M.; MacOpiyo, L.; Kenfack, D. Tracing innovation pathways in the management of natural and social capital on Laikipia Maasai Group Ranches, Kenya. Pastoralism 2016, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development Recognised Biosecurity Groups|Agriculture and Food. Available online: www.agric.wa.gov.au (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- O’Brien, L.; Ambrose-oji, B.; Hemery, G.; Raum, S. Payments for Ecosystem Services, Land Manager Networks and Social Learning; Forest Research: Farnham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Valachovic, Y.; Lee, C.; Goldsworthy, E.; Cannon, P. Novel approaches to SOD management in California wildlands: A case study of “eradication” and collaboration in Redwood Valley. In Proceedings of the Sudden Oak Death Fifth Science Symposium; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: Albany, CA, USA, 2013; pp. 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, S.D.; Koontz, T.M. Collaborative watershed partnerships in urban and rural areas: Different pathways to success? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 95, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gov.uk. Facilitation Fund: Countryside Stewardship. Available online: www.gov.uk (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Elliott, V. Thinking about the coding process in qualitative data analysis. Qual. Rep. 2018, 23, 2850–2861. [Google Scholar]

- Armat, M.R. Inductive and Deductive: Ambiguous Labels in Qualitative Content Analysis Abdolghader Assarroudi and Mostafa Rad Hassan Sharifi and Abbas Heydari. Qual. Rep. 2018, 23, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Multi-level Governance: A Conceptual Framework. In Cities and Climate Change; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 171–178. [Google Scholar]

- Mandarano, L.A. Social Network Analysis of Social Capital in Collaborative Planning. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2009, 22, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickenbach, M. Serving members and reaching others: The performance and social networks of a landowner cooperative. For. Policy Econ. 2009, 11, 593–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandefur, R.L.; Laumann, E.O. A paradigm for social capital. Ration. Soc. 1998, 10, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, R.; Toikka, A.; Primmer, E. Social capital and governance: A social network analysis of forest biodiversity collaboration in Central Finland. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 50, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trimble, M.; Lázaro, M. Evaluation criteria for participatory research: Insights from coastal Uruguay. Environ. Manag. 2014, 54, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wit-de Vries, E.; Dolfsma, W.A.; van der Windt, H.J.; Gerkema, M.P. Knowledge transfer in university–industry research partnerships: A review. J. Technol. Transf. 2019, 44, 1236–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dale, S.K.; Grimes, T.; Miller, L.; Ursillo, A.; Drainoni, M.-L. “In our stories”: The perspectives of women living with HIV on an evidence-based group intervention. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cockburn, J.; Cundill, G.; Shackleton, S.; Cele, A.; Francina, S.; Cornelius, A.; Koopman, V.; Roux, J.; Mcleod, N.; Rouget, M.; et al. Relational Hubs for Collaborative Landscape Stewardship. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, 33, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Evely, A.C.; Cundill, G.; Fazey, I.; Glass, J.; Laing, A.; Newig, J.; Parrish, B.; Prell, C.; Raymond, C.; et al. What is social learning? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauber, T.B.; Brown, T.L. Learning by Doing: Policy Learning in Community-Based Deer Management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, N.D.; Hickey, G.M.; Humphries, M.M. Understanding community-researcher partnerships in the natural sciences: A case study from the Arctic. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 36, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmer, H.; Derner, J.D.; Fernández-Giménez, M.E.; Briske, D.D.; Augustine, D.J.; Porensky, L.M.; The CARM Stakeholder Group. Collaborative Adaptive Rangeland Management Fosters Management-Science Partnerships. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 71, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, J.; Beers, P.J.; Wals, A.E.J. Social learning in regional innovation networks: Trust, commitment and reframing as emergent properties of interaction. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 49, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkpen, A.C.; Tsang, E.W.K. Social Capital, Networks, and Knowledge Transfer. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 146–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Measham, T.G. How Long Does Social Learning Take? Insights from a Longitudinal Case Study. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 1468–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reed, M.G.; Godmaire, H.; Abernethy, P.; Guertin, M.-A. Building a community of practice for sustainability: Strengthening learning and collective action of Canadian biosphere reserves through a national partnership. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kraker, J. Social learning for resilience in social–ecological systems. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 28, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzano, M.; Dandy, N.; Bayliss, H.R.; Porth, E.; Potter, C. Part of the solution? Stakeholder awareness, information and engagement in tree health issues. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 1961–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Length of Time as a Network | Type of Stakeholders Involved | Focus of Network | Methods of Data Gathering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network 1 | |||

| Short term, 2–3 years | The stakeholders were mainly part of national and local government organisations, charities and businesses, but also there were individual members such as private landowners and land agents, and also wood processing stakeholders | One sub-working group in the network. The focus of the network is on a single pest/disease primarily 1. | Six interviews were undertaken with members of the network (one person was interviewed twice). Interviews included the chair (local authority representative), the chair of a sub-group within the network (retired independent person), and two network members, one from a government body and the other from an NGO. One interview with a person (NGO) who helped to create the network but is not a current member. Researchers attended at a network meeting with a slot for a focused discussion on the research. Twenty-one people attended the network meeting excluding the researchers. |

| Network 2 | |||

| Medium term, 4–8 years | The stakeholders were part of government agencies and local government, NGOs, timber processors and members of private estates | The network focus is on two pests/diseases. | Six interviews were undertaken with members of the network including the chair (government body representative) and 5 network members, 2 of whom worked for different NGOs and 3 who worked for a government body. Researchers attended a network meeting with a slot for a focused discussion on the research. Twenty people attended the network meeting excluding the researchers. |

| Network 3 | |||

| Long term–8+ years | The stakeholders were mainly corporate members, tree managers and tree officers. Additionally, the network includes nurseries, contractors and consultants. | Members of the network pay a fee to join. The fee pays for a secretariat and network events. Numerous sub- working groups exist within the network with at least two focusing on specific pests/diseases. | Seven interviews were undertaken with members of the network (one person was interviewed twice) including the chair (local authority representative), the chair of a network sub-group (local authority), the coordinator of the network and three people from different local authorities. |

| Exchange Information, Knowledge | Run Workshops, Field Trips, etc. | Develop Guidance, Action Plans, Communication Plans | Collaborate, Share Information with Others | Influence Policy, Legislation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network 1 | ||||

| Disseminated practical information | Ran w/shop sessions at a Local Nature Partnership conference. Organised field trips. | An action plan was developed before the network was formally constituted. The network once formed developed a communication plan, 4 guidance documents prepared by a sub-group, and risk assessments. | Shared lessons with other Local Authorities in England, learned from other Local Authorities, and sought external funding. | A member of the network sits on a government panel to discuss a specific disease. |

| Network 2 | ||||

| Provided up-to-date regional tree pest and disease situation reports and information about relevant future threats | N/A | Simplified and condensed existing guidance from the national level to make it relevant to the local context. | Learned from others and shared knowledge. | Aims to influence policy. |

| Network 3 | ||||

| Disseminated information on best practice | The network runs four technical seminars per year, as well as various field trips, workshops. | Developed a position statement on biosecurity. Simplified and condensed existing guidance. | A few network members visited Italy to explore a specific pest and disease and translated relevant evidence into English. | Aims to influence policy, legislation, and raise standards. |

| Network 1 | Network 2 | Network 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes that would not have happened without the network being in place | Support an integrated approach to the tree disease response from both a public safety perspective and ecological perspective. | None to report. | Network and informal information sharing at organised social events. |

| Support and knowledge exchange with other counties to develop similar networks. | The ability to draw on the expertise of network members to develop a guidance document. | ||

| Outcomes that would have happened but would have been delayed or less comprehensive without the networks, resulting in significant consequences | The network brought attention to a disease and required a response. Due to the network, the local area is now recognised as one of the leading counties responding to the disease. | Up-to-date regional pest and disease information cascaded to members and other stakeholders. | Bringing together professionals from all sectors (due to the network members’ level of knowledge and breadth of experiences, which is seen to be unsurpassed by any other organisation) |

| The network acting as a “therapy class” for members who felt a sense of loss due to the impact of tree losses associated with a tree disease. | Information picked up and reported at an early stage for rapid management. | Dissemination of information, seminars, workshops could have been replaced, but would not be on such a wide scale and as good quality built through network relationships. | |

| The network developing capacity to engage with other organisations and attract the right group of people. The network adds credibility and authority to the work, facilitating the achievement of goals. | Benefiting from a range of contacts and at no cost when synthesising and disseminating information. | Others could have tried to undertake similar actions as an individual (e.g., synthesis and targeting information), but the content would not have been as well regarded if the network had not been involved. | |

| Broadcasting information would be more difficult because there was no one cross-sector/interest body able to fulfil this role. | |||

| Action plans and guidance documents could be developed by other organisations, but would have less impact without collective effort. | |||

| Outcomes that would have happened but would have been delayed or less comprehensive resulting in modest or minimal consequences | Action plan that was produced before network formally got together. | Gaining funding to support the work of the network. Other organisations can successfully apply for funding without the network. | Somebody else (outside of a network) would have created a biosecurity position statement (but it would have potentially taken a different angle to that of the network). |

| Capacity to raise funds (one bid was unsuccessful but the network has other funding pots in mind). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Brien, L.; Karlsdóttir, B.; Ambrose-Oji, B.; Urquhart, J.; Edwards, D.; Amboage, R.; Jones, G. How Can Local and Regional Knowledge Networks Contribute to Landscape Level Action for Tree Health? Forests 2021, 12, 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12101394

O’Brien L, Karlsdóttir B, Ambrose-Oji B, Urquhart J, Edwards D, Amboage R, Jones G. How Can Local and Regional Knowledge Networks Contribute to Landscape Level Action for Tree Health? Forests. 2021; 12(10):1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12101394

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Brien, Liz, Berglind Karlsdóttir, Bianca Ambrose-Oji, Julie Urquhart, David Edwards, Rosa Amboage, and Glyn Jones. 2021. "How Can Local and Regional Knowledge Networks Contribute to Landscape Level Action for Tree Health?" Forests 12, no. 10: 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12101394

APA StyleO’Brien, L., Karlsdóttir, B., Ambrose-Oji, B., Urquhart, J., Edwards, D., Amboage, R., & Jones, G. (2021). How Can Local and Regional Knowledge Networks Contribute to Landscape Level Action for Tree Health? Forests, 12(10), 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/f12101394