Assessing Risk and Prioritizing Safety Interventions in Human Settlements Affected by Large Wildfires

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Wildfires of 2017 in Portugal—The Case of Alvares

2. Materials and Methods

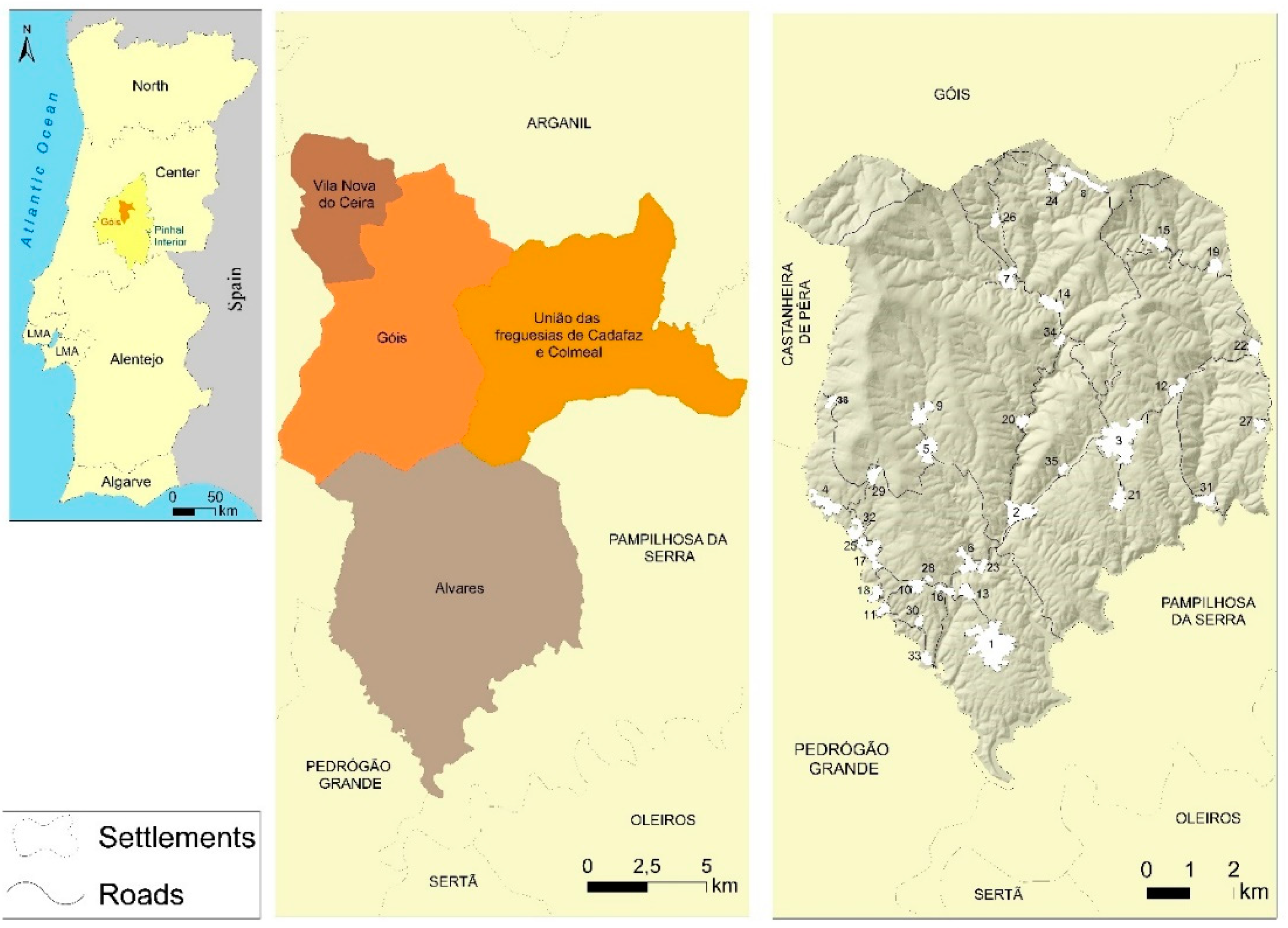

2.1. Study Area

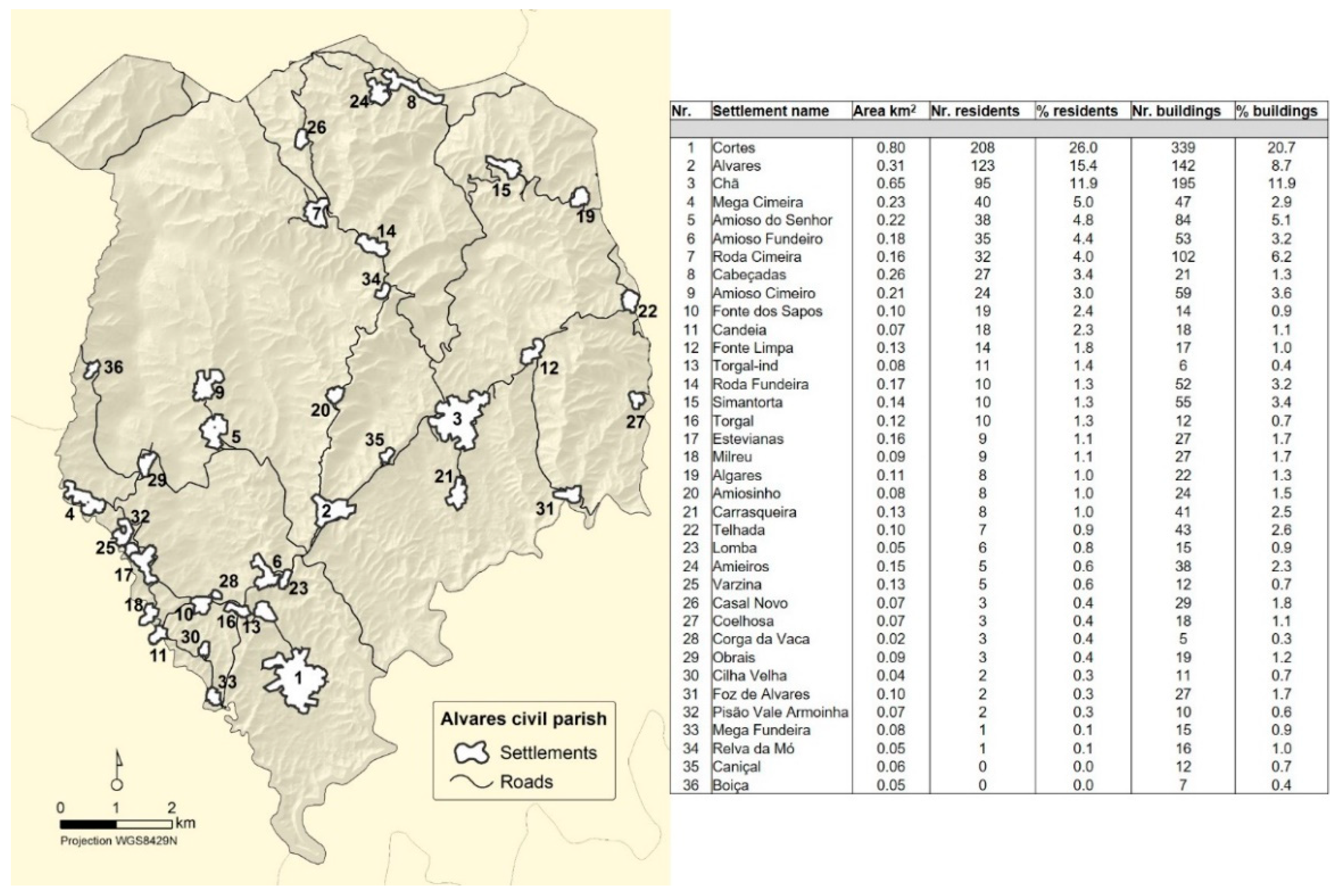

2.2. Delimitation and Characterization of the Human Settlements in Alvares

2.3. Data Collection and Risk Analysis Procedure

2.3.1. Exposure

2.3.2. Vulnerability

Coping Capacity

2.3.3. Wildfire Risk

2.4. Landscape-Level Fuel Management Scenarios

- (i)

- Forest management activities: Overall, 38% of the forest land of Alvares is intensively managed, which includes frequent fuel management (every five years), the use of genetically improved material and fertilization. About 50% of the land in the civil parish has a basic forest management, mainly limited to the tree-cutting process after the rotation period, whereas 10% of the forest land is not managed at all [49]. We considered two different levels of forest management, namely a moderate (~20%) and high (~30%) increase in managed forest area in the parish, besides the 38% already in place. The increase in forest management changes the distribution of fuels, decreasing their loads.

- (ii)

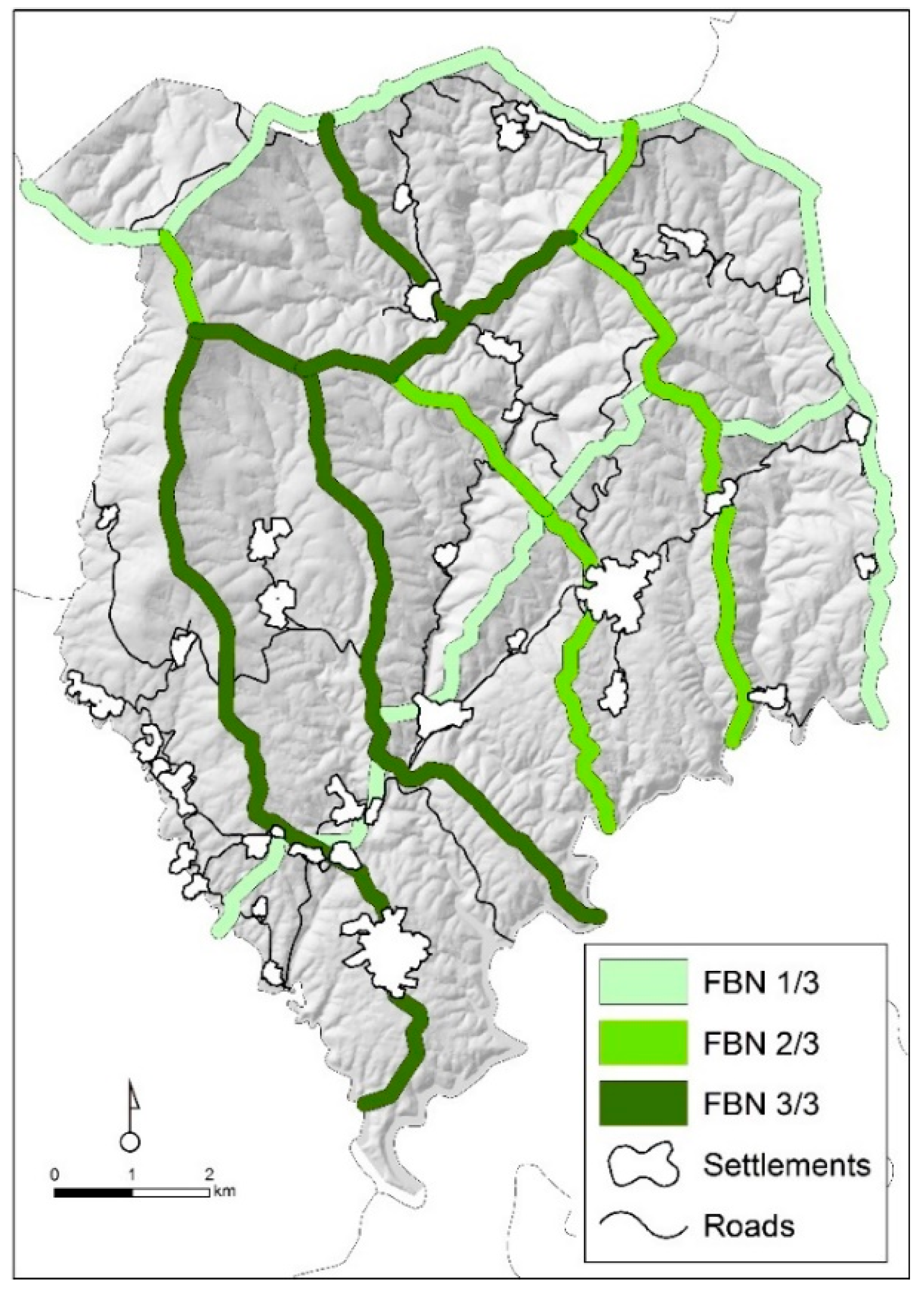

- Fuel break network (FBN): the implementation of a fuel break network is defined in the municipal plans of forest defense against wildfires, established by law since 2006 (Decree-Law 124/2006, of 28 June), and follows the technical guidelines of the National Forest Services. The network was designed with the specific function of protecting people, assets, and forested areas against wildfires, considering the topographic and hydrographic conditions, the fire history of Alvares and neighbouring parishes, and the exposure of villages [53]. The creation of a FBN implies the creation of fuel discontinuities in the landscape, reducing fuel density in selected areas. In Alvares, the fuel breaks should be located in elevated areas, in the main ridges, to support also firefighting activities, and should be at least 125 m large. We considered three different levels of fuel break network implementation: first priority (1/3 of total extent), second priority (2/3 of total extent), and the entire network (Figure 4). Each level corresponds roughly to 450 ha of land. The first priority fuel breaks were designed with the purpose to decrease the area traveled by large fires, the second priority to protect roads, infrastructures and buildings, and the third priority to isolate potential fire ignition spots. In the FBN areas, specific land uses are promoted, to ensure low fuel loads: agricultural fields, pastures, shrubs managed every 3 to 5 years, possibly with broadleaved trees planted at least 3 m apart. These fuel break network options influence the distribution of fuel types and loads in the landscape, which is reflected in the burn probability simulations. It was assumed that, in the first year, the FBN areas do not have burnable fuels, progressively increasing the fuel load to low density/low height shrubs, up to the fifth year after their implementation, when they are managed again and the cycle restarts [49].

3. Results

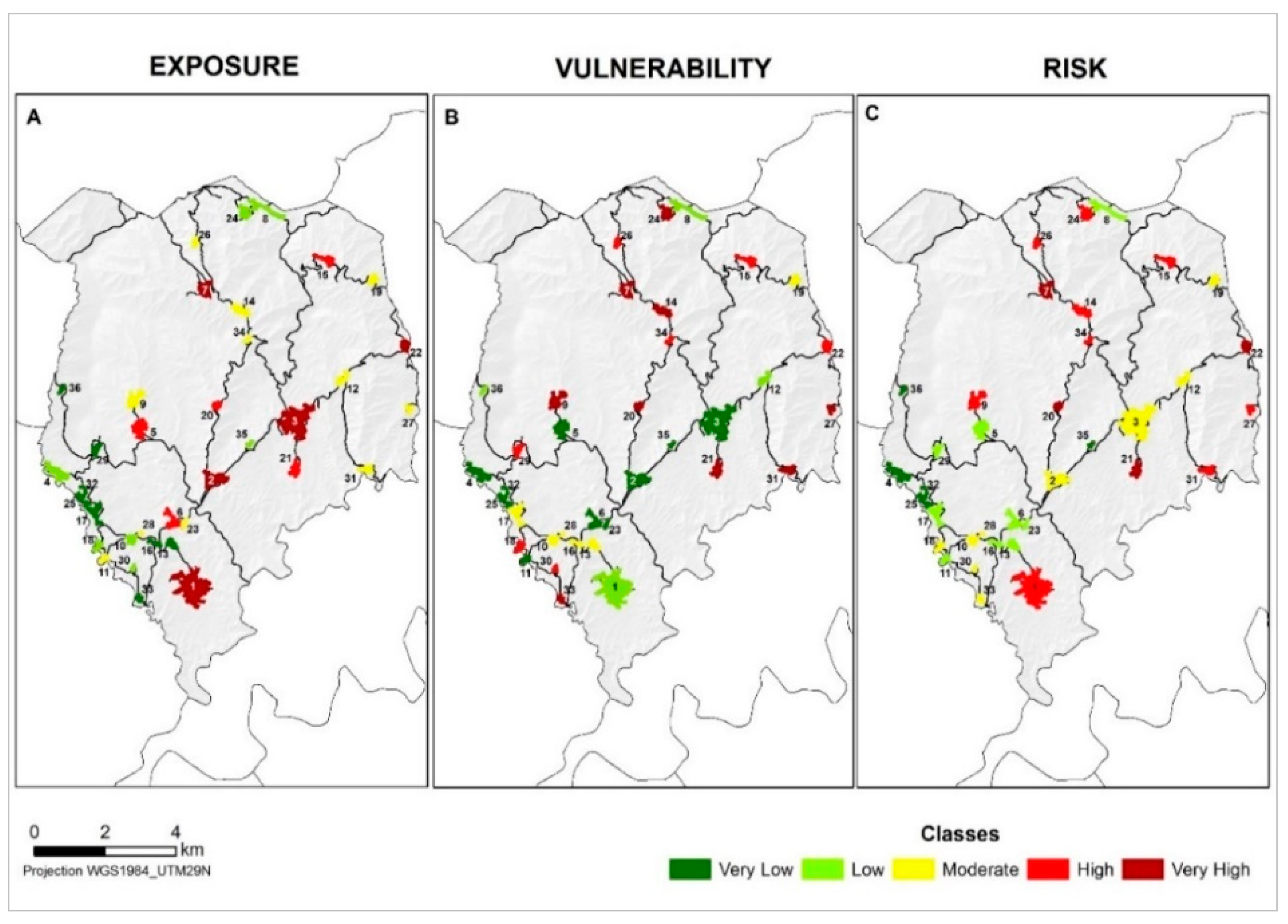

3.1. Exposure

3.2. Vulnerability and Coping Capacity

3.3. Wildfire Risk

3.4. Effects of Fuel Management Scenarios in Exposure and Risk Levels

4. Discussion

4.1. Risk Assessment at the Settlement Scale

4.2. Effects of Fuel Management Options in Exposure and Risk Levels of Settlements

4.3. Improving Preparedness and Defining Safety Interventions Within Settlements

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tedim, F.; Leone, V.; Xanthopoulos, G. A wildfire risk management concept based on a social-ecological approach in the European Union: Fire Smart Territory. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 18, 138–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Balch, J.K.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W.J.; Cochrane, M.A.; D’Antonio, C.M.; Defries, R.S.; Johnston, F.H.; Keeley, J.E.; Krawchuk, M.A.; et al. The human dimension of fire regimes on Earth. J. Biogeogr. 2011, 38, 2223–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moritz, M.A.; Batllori, E.; Bradstock, R.A.; Gill, A.M.; Handmer, J.; Hessburg, P.F.; Leonard, J.; McCaffrey, S.; Odion, D.C.; Schoennagel, T.; et al. Learning to coexist with wildfire. Nature 2014, 515, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchi, R.; Leonard, J.; Haynes, K.; Opie, K.; James, M.; Oliveira, F.D. De Environmental circumstances surrounding bushfire fatalities in Australia 1901–2011. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 37, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-González, S.; Ojeda, F.; Fernandes, P.M. Portugal and Chile: Longing for sustainable forestry while rising from the ashes. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 81, 104–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Durrant, T.; Boca, R.; Libertà, G.; Branco, A.; De Rigo, D.; Ferrari, D.; Maianti, P.; Vivancos, T.A.; Oom, D.; et al. Forest Fires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2018; EUR 29856 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; ISBN 978-92-76-11234-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauslar, N.; Abatzoglou, J.; Marsh, P. The 2017 North Bay and Southern California Fires: A Case Study. Fire 2018, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, M.S.; Paveglio, T.B. Using community archetypes to better understand differential community adaptation to wildfire risk. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaiologou, P.; Ager, A.A.; Nielsen-Pincus, M.; Evers, C.R.; Day, M.A. Social vulnerability to large wildfires in the western USA. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 189, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evers, C.R.; Ager, A.A.; Nielsen-Pincus, M.; Palaiologou, P.; Bunzel, K. Archetypes of community wildfire exposure from national forests of the western US. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 182, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Balch, J.K.; Artaxo, P.; Bond, W.J.; Carlson, J.M.; Cochrane, M.A.; D’Antonio, C.M.; Defries, R.S.; Doyle, J.C.; Harrison, S.P.; et al. Fire in the Earth system. Science 2009, 324, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prichard, S.J.; Stevens-Rumann, C.S.; Hessburg, P.F. Tamm Review: Shifting global fire regimes: Lessons from reburns and research needs. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 396, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, O.M.; Salis, M.; Ager, A.A.; Arca, B.; Alcasena, F.J.; Monteiro, A.T.; Finney, M.A.; Del Giudice, L.; Scoccimarro, E.; Spano, D. Assessing Climate Change Impacts on Wildfire Exposure in Mediterranean Areas. Risk Anal. 2017, 37, 1898–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syphard, A.D.; Sheehan, T.; Rustigian-Romsos, H.; Ferschweiler, K. Mapping future fire probability under climate change: Does vegetation matter? PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeley, J.; Syphard, A. Climate Change and Future Fire Regimes: Examples from California. Geosciences 2016, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager, A.A.; Palaiologou, P.; Evers, C.R.; Day, M.A.; Ringo, C.; Short, K. Wildfire exposure to the wildland urban interface in the western US. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 111, 102059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champ, P.A.; Donovan, G.H.; Barth, C.M. Living in a tinderbox: Wildfire risk perceptions and mitigating behaviours. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2013, 22, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, C.S.; Kline, J.D.; Ager, A.A.; Olsen, K.A.; Short, K.C. Examining the influence of biophysical conditions on wildland–urban interface homeowners’ wildfire risk mitigation activities in fire-prone landscapes. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahan, K.; Watson, S.J. The protective action decision model: When householders choose their protective response to wildfire. J. Risk Res. 2019, 22, 1602–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, T.J.; Dennison, P.E.; Drews, F.A. Modeling evacuate versus shelter-in-place decisions in wildfires. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1662–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, T.J.; Theobald, D.M.; Norman, J.B.; Siebeneck, L.K. Mapping wildfire evacuation vulnerability in the western US: The limits of infrastructure. GeoJournal 2013, 78, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Cova, T.J.; Dennison, P.E. A household-level approach to staging wildfire evacuation warnings using trigger modeling. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2015, 54, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovreglio, R.; Kuligowski, E.; Gwynne, S.; Strahan, K. A modelling framework for householder decision-making for wildfire emergencies. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 41, 101274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strahan, K.; Whittaker, J.; Handmer, J. Self-evacuation archetypes in Australian bushfire. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2018, 27, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cova, T.J.; Drews, F.A.; Siebeneck, L.K.; Musters, A. Protective actions in wildfires: Evacuate or shelter-in-place? Nat. Hazards Rev. 2009, 10, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Edgeley, C.M.; Carroll, M.; Billings, M.; Stasiewicz, A.M. Exploring the Influence of Local Social Context on Strategies for Achieving Fire Adapted Communities. Fire 2019, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Zêzere, J.L.; Queirós, M.; Pereira, J.M. Assessing the social context of wildfire-affected areas. The case of mainland Portugal. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 88, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prior, T.; Eriksen, C. Wildfire preparedness, community cohesion and social-ecological systems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1575–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigtil, G.; Hammer, R.B.; Kline, J.D.; Mockrin, M.H.; Stewart, S.I.; Roper, D.; Radeloff, V.C. Places where wildfire potential and social vulnerability coincide in the coterminous United States. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2016, 25, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.; Oliveira, S.; Zêzere, J.L.; Viegas, D.X. Uncovering the perception regarding wildfires of residents with different characteristics. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 43, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.; Jarrett, A.; Gaither, C.J. Landowner response to wildfire risk: Adaptation, mitigation or doing nothing. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 159, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, S. Community wildfire preparedness: A global state-of-the-knowledge summary of social science research. Curr. For. Rep. 2015, 1, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Moseley, C.; Carroll, M.S.; Williams, D.R.; Davis, E.J.; Fischer, A.P. Categorizing the social context of the wildland urban interface: Adaptive capacity for wildfire and community “Archetypes”. For. Sci. 2015, 61, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Prato, T.; Edgeley, C.; Nalle, D. Evaluating the Characteristics of Social Vulnerability to Wildfire: Demographics, Perceptions, and Parcel Characteristics. Environ. Manag. 2016, 58, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutter, S.L. The vulnerability of science and the science of vulnerability. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2003, 93, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkmann, J.; Cardona, O.D.; Carreño, M.L.; Barbat, A.H.; Pelling, M.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Kienberger, S.; Keiler, M.; Alexander, D.; Zeil, P.; et al. Framing vulnerability, risk and societal responses: The Move framework. Nat. Hazards 2013, 67, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, S.; Félix, F.; Nunes, A.; Lourenço, L.; Laneve, G.; Sebastián-López, A. Mapping wildfire vulnerability in Mediterranean Europe. Testing a stepwise approach for operational purposes. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ager, A.A.; Day, M.A.; Finney, M.A.; Vance-Borland, K.; Vaillant, N.M. Analyzing the transmission of wildfire exposure on a fire-prone landscape in Oregon, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 334, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, M.; Ager, A.A.; Alcasena, F.J.; Arca, B.; Finney, M.A.; Pellizzaro, G.; Spano, D. Analyzing seasonal patterns of wildfire exposure factors in Sardinia, Italy. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salis, M.; Ager, A.A.; Arca, B.; Finney, M.A.; Bacciu, V.; Duce, P. Donatella Spano Assessing exposure of human and ecological values to wildfire in Sardinia, Italy. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2013, 22, 549–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcasena, F.J.; Salis, M.; Vega-García, C. A fire modeling approach to assess wildfire exposure of valued resources in central Navarra, Spain. Eur. J. For. Res. 2016, 135, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.H.; Thompson, M.P.; Gilbertson-Day, J.W. Exploring how alternative mapping approaches influence fireshed assessment and human community exposure to wildfire. GeoJournal 2017, 82, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, C.C. Wildland fire hazard and risk: Problems, definitions, and context. For. Ecol. Manag. 2005, 211, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.P.; Spies, T.A.; Steelman, T.A.; Moseley, C.; Johnson, B.R.; Bailey, J.D.; Ager, A.A.; Bourgeron, P.; Charnley, S.; Collins, B.M.; et al. Wildfire risk as a socioecological pathology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2016, 14, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Durrant, T.; Boca, R.; Libertà, G.; Branco, A.; De Rigo, D.; Ferrari, D.; Maianti, P.; Vivancos, T.A.; Costa, H.; et al. Forest Fires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2017; EUR 29318 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019; ISBN 978-92-79-92831-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turco, M.; Jerez, S.; Augusto, S.; Tarín-Carrasco, P.; Ratola, N.; Jiménez-Guerrero, P.; Trigo, R.M. Climate drivers of the 2017 devastating fires in Portugal. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellnou, M.; Guiomar, N.; Rego, F.; Fernandes, P.M. Fire growth patterns in the 2017 mega fire episode of October 15, central Portugal. In Advances in Forest Fire Research 2018; Viegas, D.X., Ed.; Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 447–453. ISBN 9789892616506. [Google Scholar]

- Boer, M.M.; Nolan, R.H.; De Dios, V.R.; Clarke, H.; Owen, F.; Bradstock, R.A. Changing Weather Extremes Call for Early Warning of Potential for Catastrophic Fire. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.M.; Benali, A.; Sá, A.; Le Page, Y.; Barreiro, S.; Rua, J.; Tomé, M.; Santos, J.M.L.; Canadas, M.J.; Martins, A.P.; et al. Alvares, um Caso de Resiliência ao Fogo (Relatório Técnico); Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Canadas, M.J.; Novais, A.; Marques, M. Wildfires, forest management and landowners’ collective action: A comparative approach at the local level. Land Use Policy 2016, 56, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.C.D.N. Avaliação da Exposição das Comunidades Locais a Incêndios Florestais. O caso de Alvares, Góis; Universidade de Lisboa: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- INE. Censos 2011: Resultados definitivos-Portugal; Instituto Nacional de Estatistica: Lisbon, Portugal, 2012.

- Benali, A.; Sá, A.; Barreiro, S.; Pereira, J.M. Assessing the impact of landscape management strategies on the exposure to large wildfires. Forests 2020. Unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- DGT Carta de Uso e Ocupação do Solo de Portugal Continental Para 2015—COS2015. 2018. Available online: www.dgterritorio.gov.pt (accessed on 15 January 2018).

- Fernandes, P. Equivalência Genérica Entre os Modelos de Combustível do USDA Forest Service (Anderson, 1982) e as Formações Florestais Portuguesas; Guia metodológico para elaboração do Plano Municipal/Intermunicipal de Defesa da Floresta Contra Incêndios; Direção Geral dos Recursos Florestais: Lisboa, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Finney, M.A. FARSITE: Fire Area Simulator—Model Development and Evaluation; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Washington, DC, USA; Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1998.

- AFN; Plano Municipal de Defesa da Floresta Contra Incêndios (PMDFCI). Guia Técnico; Direcção de Unidade de Defesa da Floresta: Lisboa, Portugal, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, J.H., Jr. Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1963, 58, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, N.J.; Schmidtlein, M.C. Anisotropic path modeling to assess pedestrian-evacuation potential from Cascadia-related tsunamis in the US Pacific Northwest. Nat. Hazards 2012, 62, 275–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M.; Ng, P.; Wood, N.J. The Pedestrian Evacuation Analyst: Geographic Information Systems Software for Modeling Hazard Evacuation Potential; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2014.

- Fathani, T.F.; Karnawati, D.; Wilopo, W. An integrated methodology to develop a standard for landslide early warning systems. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2016, 16, 2123–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, R.; Zêzere, J.L.; Oliveira, S.C.; Garcia, R.A.C.; Oliveira, S.; Pereira, S.; Piedade, A.; Santos, P.P.; Van Asch, T.W.J. Defining evacuation travel times and safety areas in a debris flow hazard scenario. Sci. Total Environ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soule, R.G.; Goldman, R.F. Terrain coefficients for energy cost prediction. J. Appl. Physiol. 1972, 32, 706–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W. Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20-79 years: Reference values and determinants. Age Ageing 1997, 26, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roush, J.; Bay, R.C. Percentile Ranks for Walking Speed in Subjects 70–79 Years: A Meta-analysis. J. Allied Heal. Sci. Pract. 2014, 12, 5. [Google Scholar]

- OTI Observatório Técnico Independente; Castro Rego, F.; Fernandes, P.; Sande Silva, J.; Azevedo, J.; Moura, J.M.; Oliveira, E.; Cortes, R.; Viegas, D.X.; Caldeira, D.; et al. A Valorização da Primeira Intervenção no Combate a Incêndios Rurais; Assembleia da República: Lisboa, Portugal, 2019; p. 38.

- Thompson, M.P.; Haas, J.R.; Gilbertson-Day, J.W.; Scott, J.H.; Langowski, P.; Bowne, E.; Calkin, D.E. Development and application of a geospatial wildfire exposure and risk calculation tool. Environ. Model. Softw. 2015, 63, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Aguado, I.; Yebra, M.; Nieto, H.; Salas, P.J.; Martín, M.P.; Vilar, L.; Martínez, J.; Martíin, S.; Ibarra, P.; et al. Development of a framework for fire risk assessment using remote sensing and geographic information system technologies. Ecol. Model. 2010, 221, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuvieco, E.; Aguado, I.; Jurdao, S.; Pettinari, M.L.; Yebra, M.; Salas, J.; Hantson, S.; De La Riva, J.; Ibarra, P.; Rodrigues, M.; et al. Integrating geospatial information into fire risk assessment. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2014, 23, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.; Ager, A.A. A review of recent advances in risk analysis for wildfire management. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2013, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcasena, F.J.; Salis, M.; Ager, A.A.; Arca, B.; Molina, D.; Spano, D. Assessing Landscape Scale Wildfire Exposure for Highly Valued Resources in a Mediterranean Area. Environ. Manag. 2015, 55, 1200–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaiologou, P.; Ager, A.A.; Nielsen-Pincus, M.; Evers, C.R.; Kalabokidis, K. Using transboundary wildfire exposure assessments to improve fire management programs: A case study in Greece. Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2018, 27, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L.; Boruff, B.J.; Shirley, W.L. Social Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards. Soc. Sci. Q. 2003, 84, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Carroll, M.S.; Stasiewicz, A.M.; Williams, D.R.; Becker, D.R. Incorporating social diversity into wildfire management: Proposing “Pathways” for fire adaptation. For. Sci. 2018, 64, 515–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Brennan, T.J.; Keeley, J.E. The importance of building construction materials relative to other factors affecting structure survival during wildfire. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 21, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paveglio, T.B.; Jakes, P.J.; Carroll, M.S.; Williams, D.R. Understanding social complexity within the wildland-urban interface: A new species of human habitation? Environ. Manag. 2009, 43, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salis, M.; Laconi, M.; Ager, A.A.; Alcasena, F.J.; Arca, B.; Lozano, O.; Fernandes de Oliveira, A.; Spano, D. Evaluating alternative fuel treatment strategies to reduce wildfire losses in a Mediterranean area. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 368, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradstock, R.A.; Cary, G.J.; Davies, I.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Price, O.F.; Williams, R.J. Wildfires, fuel treatment and risk mitigation in Australian eucalypt forests: Insights from landscape-scale simulation. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 105, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager, A.A.; Vaillant, N.M.; Finney, M.A. A comparison of landscape fuel treatment strategies to mitigate wildland fire risk in the urban interface and preserve old forest structure. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 1556–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, O.F.; Bradstock, R.A. The efficacy of fuel treatment in mitigating property loss during wildfires: Insights from analysis of the severity of the catastrophic fires in 2009 in Victoria, Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 113, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calkin, D.E.; Cohen, J.D.; Finney, M.A.; Thompson, M.P. How risk management can prevent future wildfire disasters in the wildland-urban interface. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 746–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, P.; Van Bommel, L.; Gill, A.M.; Cary, G.J.; Driscoll, D.A.; Bradstock, R.A.; Knight, E.; Moritz, M.A.; Stephens, S.L.; Lindenmayer, D.B. Land management practices associated with house loss in wildfires. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e0029212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcasena, F.J.; Ager, A.A.; Salis, M.; Day, M.A.; Vega-Garcia, C. Optimizing prescribed fire allocation for managing fire risk in central Catalonia. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 872–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salis, M.; Del Giudice, L.; Arca, B.; Ager, A.A.; Alcasena, F.J.; Lozano, O.; Bacciu, V.; Spano, D.; Duce, P. Modeling the effects of different fuel treatment mosaics on wildfire spread and behavior in a Mediterranean agro-pastoral area. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 212, 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcasena, F.J.F.J.; Ager, A.A.; Bailey, J.D.; Pineda, N.; Vega-García, C. Towards a comprehensive wildfire management strategy for Mediterranean areas: Framework development and implementation in Catalonia, Spain. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, P.; Gill, A.M.; Shore, N.; Moritz, M.A.; Dovers, S.; Cary, G.J. Options for reducing house-losses during wildfires without clearing trees and shrubs. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 174, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, P.D.; Penman, T.D. Is there an inherent conflict in managing fire for people and conservation? Int. J. Wildl. Fire 2017, 26, 455–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffrey, S.; Wilson, R.; Konar, A. Should I Stay or Should I Go Now? Or Should I Wait and See? Influences on Wildfire Evacuation Decisions. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 1390–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podur, J.; Wotton, M. Will climate change overwhelm fire management capacity? Ecol. Model. 2010, 221, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, F.; Ascoli, D.; Safford, H.; Adams, M.A.; Moreno, J.M.; Pereira, J.M.C.; Catry, F.X.; Armesto, J.; Bond, W.; González, M.E.; et al. Wildfire management in Mediterranean-type regions: Paradigm change needed. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.M. Fire-smart management of forest landscapes in the Mediterranean basin under global change. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 110, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Format | Resolution/Scale | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | Burn Probability (hazard) | Raster | 1 ha | FuncSim, FARSITE |

| Population density | Vector | Subsection | National Statistics (2011) Field work (2018) | |

| Buildings density | Vector | Subsection | ||

| Vulnerability | % women | Vector | Subsection | National Statistics (2011) |

| % young people (<20 years old) | ||||

| % elderly people (>64 years old) | ||||

| % illiterate people | ||||

| % people with elementary school level | ||||

| % people with secondary school levels | ||||

| % people with university education | ||||

| % unemployed people | ||||

| % active working population | ||||

| % people working in the primary sector | ||||

| % isolated buildings | ||||

| % buildings built until 1980 | ||||

| % buildings made of stone and adobe | ||||

| % vacant housing | ||||

| Coping Capacity | Land Use and Land Cover types | Vector | 1:25,000 | DGT (2018) |

| Digital Elevation Model | Raster | 5 m (1:25,000) | DGT (2018) | |

| Road network | Vector | 1:25,000 | HERE (2005) | |

| Individualized Buildings | Vector | 1:2000 | Góis Municipality (2018) | |

| Shelters (safe zones) | Vector | 1:2000 | Field work (2018) |

| Class | SCV * | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Paved roads | 1 | Preferable path |

| Artificial surfaces | 0.9091 | Travel is easier and recommended |

| Pastures | 0.6667 | Travel is easier |

| Sparse vegetation | 0.6667 | Travel is easier |

| Agriculture | 0.5556 | Travel is possible, ease depends on farming type |

| Shrubland | 0.2778 | Travel is possible, a bit easier than forest but not advisable |

| Eucalyptus forest | 0.1389 | Travel is possible, but difficult and not advisable |

| Pine forest | 0.1389 | Travel is possible, but difficult and not advisable |

| Other forest | 0.1389 | Travel is possible, but difficult and not advisable |

| Water | 0 | No travel is possible |

| Code | Scenarios | Fuel Break Network | Forest Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sc0 | Current scenario (BAU) | No implementation | Low (38%) |

| Sc1 | Scenario Mod_Mngt | No implementation | Moderate (+20%) |

| Sc2 | Scenario High_Mngt | No implementation | High (+30%) |

| Sc3 | Scenario FBN_1/3 | Implementation of first priority (1/3) | Low (38%) |

| Sc4 | Scenario FBN_2/3 | Implementation of first and second priority (2/3) | Low (38%) |

| Sc5 | Scenario FBN_3/3 | Full Implementation, all priorities (3/3) | Low (38%) |

| Sc6 | Scenario FBN_1/3_Mod_Mngt | Implementation of first priority (1/3) | Moderate (+20%) |

| Sc7 | Scenario FBN_1/3_High_Mngt | Implementation of first priority (1/3) | High (+30%) |

| Sc8 | Scenario FBN_2/3_Mod_Mngt | Implementation of first and second priority (2/3) | Moderate (+20%) |

| Sc9 | Scenario FBN_2/3_High_Mngt | Implementation of first and second priority (2/3) | High (+30%) |

| Sc10 | Scenario FBN_3/3_Mod_Mngt | Full Implementation, all priorities (3/3) | Moderate (+20%) |

| Sc11 | Scenario FBN_3/3_High_Mngt | Full Implementation, all priorities (3/3) | High (+30%) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliveira, S.; Gonçalves, A.; Benali, A.; Sá, A.; Zêzere, J.L.; Pereira, J.M. Assessing Risk and Prioritizing Safety Interventions in Human Settlements Affected by Large Wildfires. Forests 2020, 11, 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11080859

Oliveira S, Gonçalves A, Benali A, Sá A, Zêzere JL, Pereira JM. Assessing Risk and Prioritizing Safety Interventions in Human Settlements Affected by Large Wildfires. Forests. 2020; 11(8):859. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11080859

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliveira, Sandra, Ana Gonçalves, Akli Benali, Ana Sá, José Luís Zêzere, and José Miguel Pereira. 2020. "Assessing Risk and Prioritizing Safety Interventions in Human Settlements Affected by Large Wildfires" Forests 11, no. 8: 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11080859

APA StyleOliveira, S., Gonçalves, A., Benali, A., Sá, A., Zêzere, J. L., & Pereira, J. M. (2020). Assessing Risk and Prioritizing Safety Interventions in Human Settlements Affected by Large Wildfires. Forests, 11(8), 859. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11080859