The Dark Septate Endophytes and Ectomycorrhizal Fungi Effect on Pinus tabulaeformis Carr. Seedling Growth and their Potential Effects to Pine Wilt Disease Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant and Fungal Materials

2.2. Inoculation Method

2.3. Parameter Measurement and Harvest

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. P. tabuliformis Seedling Growth and Fungal Colonization

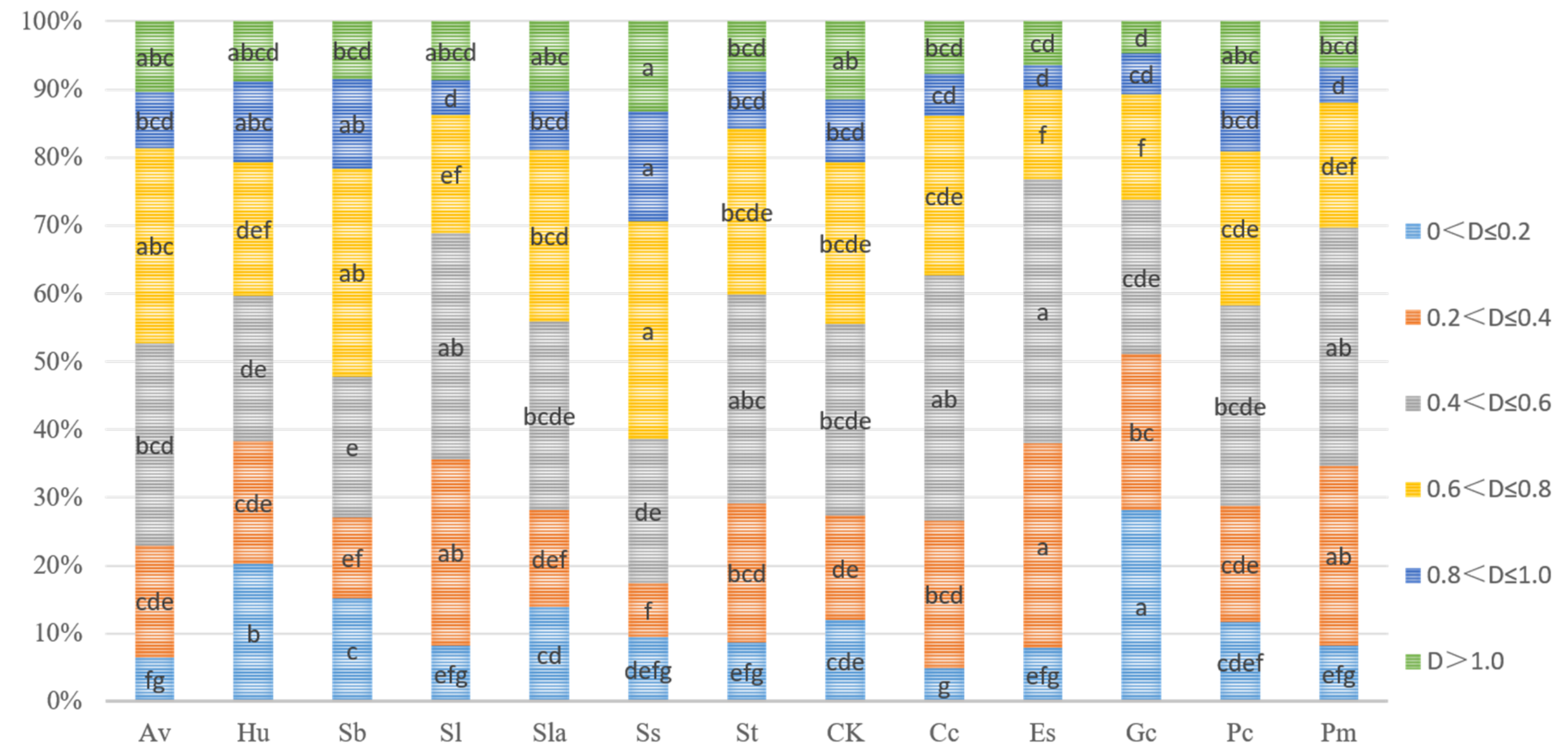

3.2. Effects of Inoculation ECMF and DSE on Roots Parameters

3.3. Pigment Parameters of Pine Needles in Different ECMF and DSE Inoculation Treatments

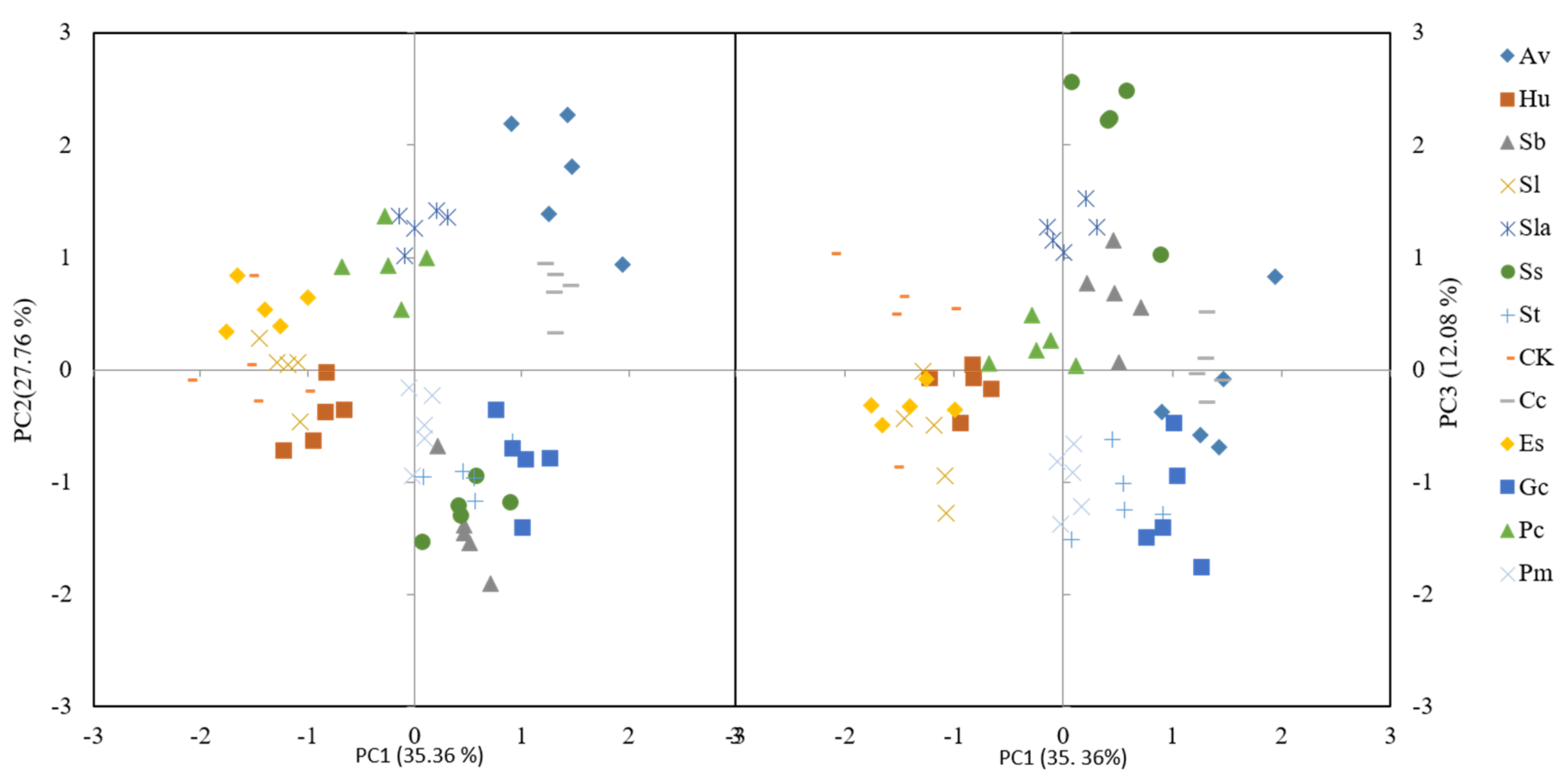

3.4. Comparison Among Strains in Principal Component Analysis

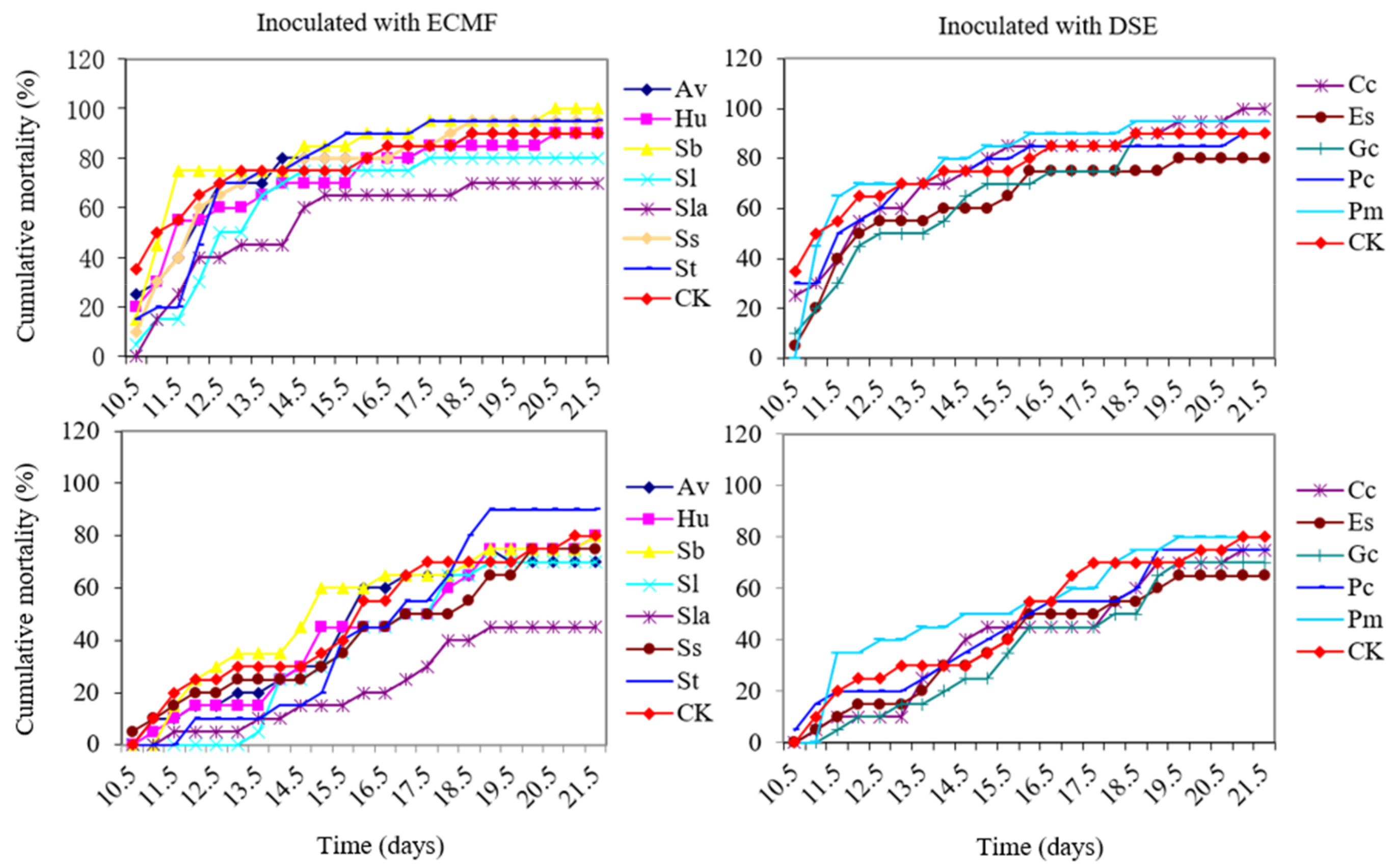

3.5. Cumulative Morbidity and Mortality of ECMF and DSE Pine Seedlings Caused by PWN

3.6. Correlation Analysis of Variables with Cumulative Mortality and Morbidity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mota, M.M.; Vieira, P. Pine Wilt Disease: A Worldwide Threat to Forest Ecosystems; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente, C.; Espada, M.; Vieira, P.; Mota, M. Pine wilt disease: A threat to European forestry. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 133, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, G.; Buhrer, E.M. Aphelenchoides xylophilus n. sp., a nematode associated with blue-stain and other fungi in timber. J. Agric. Res. 1934, 48, 949–951. [Google Scholar]

- Nickle, W.; Golden, A.; Mamiya, Y.; Wergin, W. On the taxonomy and morphology of the pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Steiner &Buhrer 1934) Nickle 1970. J. Nematol. 1981, 13, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kiyohara, T.; Tokushige, Y. Inoculation experiments of a nematode, Bursaphelenchus sp., onto pine trees. J. Jpn. For. Soc. 1997, 153, 210–218. [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa, Y.; Togashi, K. Newly discovered transmission pathway of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus from males of the beetle Monochamus alternatus to Pinus densiflora trees via oviposition wounds. J. Nematol. 2002, 34, 396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Linit, M. Nemtaode-vector relationships in the pine wilt disease system. J. Nematol. 1988, 20, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mamiya, Y.; Enda, N. Transmission of Bursaphelenchus lignicolus (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae) by Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). Nematologica 1972, 18, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimoto, K.; Iwasaki, A. Role of Monochamus alternatus (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) as a vector of Bursaphelenchus lignicolus (Nematoda: Aphelenchoididae). J. Jpn. For. Soc. 1972, 54, 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield, M.; Blanchette, R. The pine-wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, in Minnesota and Wisconsin: Insect associates and transmission studies. Can. J. Forest Res. 1983, 13, 1068–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futai, K. Pine wood nematode, Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2013, 51, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazaki, K.; Takanashi, T.; Kanzaki, N.; Komatsu, M.; Levia, D.F.; Kabeya, D.; Tobita, H.; Kitao, M.; Ishida, A. Pine wilt disease causes cavitation around the resin canals and irrecoverable xylem conduit dysfunction. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 69, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.G.; Futai, K.; Sutherland, J.R.; Takeuchi, Y. Pine Wilt Disease; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2008; pp. 144–161. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Chen, H.; Tang, M. Pine wilt disease alters soil properties and root-associated fungal communities in Pinus tabulaeformis forest. Plant Soil 2016, 404, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Pautler, M.; Massicotte, H.B.; Peterson, R.L. The co-occurrence of ectomycorrhizal, arbuscular mycorrhizal, and dark septate fungi in seedlings of four members of the Pinaceae. Mycorrhiza 2008, 18, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Tang, M.; Wang, H.; Wang, C. Pinewood nematode infection alters root mycoflora of Pinus tabulaeformis Carr. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, H.; Tang, M. Prior contact of Pinus tabulaeformis with ectomycorrhizal fungi increases plant growth and survival from damping-off. New For. 2017, 48, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Q.; Tang, M.; Chen, H.; Tian, Z.Q. Effects of ectomycorrhizal fungi on damping-off and induction of pathogenesis-related proteins in Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings inoculated with Amanita vaginata. For. Pathol. 2011, 41, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickel, U.; Winkler, J.; Mühlhans, S.; Buegger, F.; Munch, J.; Pritsch, K. Nitrogen fertilisation reduces sink strength of poplar ectomycorrhizae during recovery after drought more than phosphorus fertilisation. Plant Soil 2017, 419, 405–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.-B.; Janz, D.; Jiang, X.; Göbel, C.; Wildhagen, H.; Tan, Y.; Rennenberg, H.; Feussner, I.; Polle, A. Upgrading root physiology for stress tolerance by ectomycorrhizas: Insights from metabolite and transcriptional profiling into reprogramming for stress anticipation. Plant Physiol. 2009, 151, 1902–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumpponen, A.; Trappe, J.M. Dark septate endophytes: A review of facultative biotrophic root-colonizing fungi. New Phytol. 1998, 140, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsham, K.K. A meta-analysis of plant responses to dark septate root endophytes. New Phytol. 2011, 190, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Y.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H.; Tang, M. Effect of dark septate endophytic fungus Gaeumannomyces cylindrosporus on plant growth, photosynthesis and Pb tolerance of maize (Zea mays L.). Pedosphere 2017, 27, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandyam, K.G.; Jumpponen, A. Mutualism–parasitism paradigm synthesized from results of root-endophyte models. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trappe, J.M. Selection of fungi for ectomycorrhizal inoculation in nurseries. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1977, 15, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor-Peregrín, E.; Azcón, R.; Martos, V.; Verdejo-Lucas, S.; Talavera, M. Effects of dual inoculation of mycorrhiza and endophytic, rhizospheric or parasitic bacteria on the root-knot nematode disease of tomato. Biocontrol Sci. Techn. 2014, 24, 1122–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.Z.; Mao, L.J.; Li, N.; Feng, X.X.; Yuan, Z.L.; Wang, L.W.; Lin, F.C.; Zhang, C.L. Evidence for biotrophic lifestyle and biocontrol potential of dark septate endophyte Harpophora oryzae to rice blast disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khastini, R.O.; Ohta, H.; Narisawa, K. The role of a dark septate endophytic fungus, Veronaeopsis simplex Y34, in Fusarium disease suppression in Chinese cabbage. J. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scattolin, L.; Dal Maso, E.; Mutto Accordi, S.; Sella, L.; Montecchio, L. Detecting asymptomatic ink-diseased chestnut trees by the composition of the ectomycorrhizal community. For. Pathol. 2012, 42, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, P.; Messmer, M.M. Breeding for mycorrhizal symbiosis: Focus on disease resistance. Euphytica 2017, 213, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, H.; Eguchi, N.; Uesugi, T.; Yamashita, N.; Matsuda, Y. Effect of ectomycorrhizal composition on survival and growth of Pinus thunbergii seedlings varying in resistance to the pine wilt nematode. Trees 2016, 30, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whipps, J.M. Prospects and limitations for mycorrhizas in biocontrol of root pathogens. Can. J. Botany 2004, 82, 1198–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nara, K. Pioneer dwarf willow may facilitate tree succession by providing late colonizers with compatible ectomycorrhizal fungi in a primary successional volcanic desert. New Phytol. 2006, 171, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akema, T.; Futai, K. Ectomycorrhizal development in a Pinus thunbergii stand in relation to location on a slope and effect on tree mortality from pine wilt disease. J. For. Res-JNP. 2005, 10, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugawa, S.; Ichihara, Y.; Fukuda, K.; Suzuki, K. Ectomycorrhizae and ectomycorrhizal fungal fruit bodies in pine stands differentially damaged by pine wilt disease. Mycoscience 2009, 50, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, Y.; Tang, M.; Chen, H.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y. The response of dark septate endophytes (DSE) to heavy metals in pure culture. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, M.; Zhang, R.Q.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H.H.; Tian, Z.Q. Induced hydrolytic enzymes of ectomycorrhizal fungi against pathogen Rhizoctonia solani. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008, 30, 1777–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.Q.; Tang, M. Role of hydrogen peroxide and antioxidative enzymes in Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings inoculated with Amanita vaginata and/or Rhizoctonia solani. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2012, 134, 381–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, D.R.; Arnon, D.I. The water-culture method for growing plants without soil. Calif. Agric. Exp. Stn. Grc. 1950, 347, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Clemensson-Lindell, A. Triphenyltetrazolium chloride as an indicator of fine-root vitality and environmental stress in coniferous forest stands: Applications and limitations. Plant Soil 1994, 159, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappelle, E.W.; Kim, M.S.; McMurtrey, J.E. Ratio analysis of reflectance spectra (RARS): An algorithm for the remote estimation of the concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and carotenoids in soybean leaves. Remote Sens. Environ. 1992, 39, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.; Hayman, D. Improved procedures for clearing roots and staining parasitic and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi for rapid assessment of infection. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1970, 55, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannetti, M.; Mosse, B. An evaluation of techniques for measuring vesicular arbuscular mycorrhizal infection in roots. New Phytol. 1980, 84, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbett, D.S.; Gilbert, L.-B.; Donoghue, M.J. Evolutionary instability of ectomycorrhizal symbioses in basidiomycetes. Nature 2000, 407, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, N.; Graham, J.H.; Smith, F. Functioning of mycorrhizal associations along the mutualism-parasitism continuum. New Phytol. 1997, 135, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reininger, V.; Sieber, T.N. Mycorrhiza reduces adverse effects of dark septate endophytes (DSE) on growth of conifers. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeksema, J.D.; Chaudhary, V.B.; Gehring, C.A.; Johnson, N.C.; Karst, J.; Koide, R.T.; Pringle, A.; Zabinski, C.; Bever, J.D.; Moore, J.C.; et al. A meta-analysis of context-dependency in plant response to inoculation with mycorrhizal fungi. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 13, 394–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.; Chen, W.; Adams, T.S.; Wei, X.; Li, L.; McCormack, M.L.; DeForest, J.L.; Koide, R.T.; Eissenstat, D.M. Mycorrhizal fungi and roots are complementary in foraging within nutrient patches. Ecology 2016, 97, 2815–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Li, H.; Zhu, B.; Koide, R.T.; Eissenstat, D.M.; Guo, D. Complementarity in nutrient foraging strategies of absorptive fine roots and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi across 14 coexisting subtropical tree species. New Phytol. 2015, 208, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Koide, R.T.; Adams, T.S.; DeForest, J.L.; Cheng, L.; Eissenstat, D.M. Root morphology and mycorrhizal symbioses together shape nutrient foraging strategies of temperate trees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8741–8746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, N.; Liu, T.; Chen, H.; Tang, M. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal inoculation on water status and photosynthesis of Populus cathayana males and females under water stress. Physiol. Plantarum 2015, 155, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narisawa, K.; Tokumasu, S.; Hashiba, T. Suppression of clubroot formation in Chinese cabbage by the root endophytic fungus, Heteroconium chaetospira. Plant Pathol. 1998, 47, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandyam, K.; Jumpponen, A. Seeking the elusive function of the root-colonising dark septate endophytic fungi. Stud. Mycol. 2005, 53, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, J.; Tsuno, N.; Futai, K. The effect of mycorrhizae as a resistance factor of pine trees (Pinus densiflora) to the pinewood nematode. J. Jpn. For. Soc. 1991, 73, 216–218. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.H. What do root pathogens see in mycorrhizas? New Phytol. 2001, 149, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, A.; Strasser, R.; Martins-Loução, M. Are mycorrhiza always beneficial? Plant Soil 2006, 279, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.; Menge, J.; Erwin, D. Influence of Glomus fasciculatus and soil phosphorus on Verticillium wilt of cotton. Phytopathology 1979, 69, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes da Silva, M.; Lima, M.; Vasconcelos, M. Susceptibility evaluation of Picea abies and Cupressus lusitanica to the pine wood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus). Plant Pathol. 2013, 62, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K. Physiological process of the symptom development and resistance mechanism in pine wilt disease. J. For. Res-JPN. 1997, 2, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihara, Y.; Fukuda, K.; Suzuki, K. The effect of periderm formation in the cortex of Pinus thunbergii on early invasion by the pinewood nematode. For. Pathol. 2000, 30, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, N.; Takeuchi, Y. Histological analysis for mechanism of pine wilt disease. J. Jpn. For. Soc. 2006, 88, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumla, J.; Hobbie, E.A.; Suwannarach, N.; Lumyong, S. The ectomycorrhizal status of a tropical black bolete, Phlebopus portentosus, assessed using mycorrhizal synthesis and isotopic analysis. Mycorrhiza 2016, 26, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhsin, T.; Zwiazek, J. Ectomycorrhizas increase apoplastic water transport and root hydraulic conductivity in Ulmus americana seedlings. New Phytol. 2002, 153, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipfer, T.; Wohlgemuth, T.; van der Heijden, M.G.; Ghazoul, J.; Egli, S. Growth response of drought-stressed Pinus sylvestris seedlings to single-and multi-species inoculation with ectomycorrhizal fungi. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bingham, M.A.; Simard, S. Ectomycorrhizal networks of Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca trees facilitate establishment of conspecific seedlings under drought. Ecosystems 2012, 15, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.; Huygens, D.; Fernandez, C.; Gacitua, Y.; Olivares, E.; Saavedra, I.; Alberdi, M.; Valenzuela, E. Effect of ectomycorrhizal colonization and drought on reactive oxygen species metabolism of Nothofagus dombeyi roots. Tree Physiol. 2009, 29, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Strains | R/S Ratio | Height | Diameter | Water Content | Dry Weight (g) | Root Activity | Root Colonization Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECMF | Av | 0.48 ± 0.07 cd | 5.34 ± 0.26 ab | 1.67 ± 0.06 a | 0.77 ± 0.04 a | 0.26 ± 0.035 bc | 8.49 ± 1.67 b | 48.88 ± 8.24 c |

| Hu | 0.53 ± 0.04 cd | 4.20 ± 0.17 d | 1.35 ± 0.06 ef | 0.63 ± 0.05 e | 0.19 ± 0.041 efg | 7.43 ± 1.49 bcde | 63.45 ± 7.24 b | |

| Sb | 0.57 ± 0.05 cd | 4.20 ± 0.25 d | 1.26 ± 0.07 f | 0.62 ± 0.02 e | 0.17 ± 0.013 gf | 5.11 ± 1.76 f | 69.84 ± 9.38 ab | |

| Sl | 0.37 ± 0.04 d | 5.22 ± 0.11 abc | 1.38 ± 0.06 cde | 0.69 ± 0.03 bcd | 0.14 ± 0.022 h | 7.95 ± 1.22 bcd | 62.53 ± 3.36 b | |

| Sla | 0.62 ± 0.03 bcd | 5.36 ± 0.32 a | 1.44 ± 0.09 cd | 0.72 ± 0.03 ab | 0.34 ± 0.034 a | 7.46 ± 1.20 bcde | 64.33 ± 7.11 b | |

| Ss | 0.61 ± 0.11 bcd | 4.88 ± 0.33 c | 1.31 ± 0.09 ef | 0.65 ± 0.02 cde | 0.24 ± 0.007 bcd | 2.98 ± 1.21 g | 33.33 ± 4.84 d | |

| St | 0.88 ± 0.63 ab | 5.16 ± 0.32 abc | 1.39 ± 0.06cde | 0.54 ± 0.09 f | 0.19 ± 0.050 fg | 7.83 ± 0.97 bcd | 70.72 ± 5.71 ab | |

| Control | CK | 0.65 ± 0.15 abcd | 4.80 ± 0.36 c | 1.45 ± 0.02 c | 0.64 ± 0.02 de | 0.22 ± 0.011 def | 6.56 ± 1.78 cdef | 6.48 ± 3.16 e |

| DSE | Cc | 0.49 ± 0.05 cd | 4.90 ± 0.35 c | 1.55 ± 0.08 b | 0.72 ± 0.03 ab | 0.32 ± 0.017 a | 7.63 ± 0.80 bcd | 73.88 ± 7.92 ab |

| Es | 0.69 ± 0.21 abc | 4.84±0.30 c | 1.36 ± 0.03 de | 0.70 ± 0.01 bc | 0.22 ± 0.0197 def | 5.81 ± 0.54 ef | 48.53 ± 7.63 c | |

| Gc | 0.53 ± 0.06 cd | 5.12 ± 0.33 abc | 1.56 ± 0.04 b | 0.67 ± 0.04 bcde | 0.18 ± 0.016 fg | 8.07 ± 1.56 bc | 79.28 ± 2.72 a | |

| Pc | 0.91 ± 0.12 a | 5.14 ± 0.11 abc | 1.45 ± 0.08 cd | 0.63 ± 0.04 e | 0.27 ± 0.009 b | 6.18 ± 0.47 def | 23.33 ± 2.88 d | |

| Pm | 0.57 ± 0.13 cd | 4.92 ± 0.39 bc | 1.33 ± 0.06 ef | 0.68 ± 0.03 bcde | 0.23 ± 0.024 bcde | 10.70 ± 0.55 a | 46.45 ± 5.91 c | |

| ANOVA | F | 2.849 | 8.03 | 14.75 | 9.99 | 23.38 | 10.83 | 35.623 |

| Sig. | * | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | |

| Strains | Root Length (cm) | Root Surface Area (cm2) | Avg. Root Diameter (cm) | Root Volume (cm3) | No. of Root Tips | No. of Root Forks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Av | 228.3 ± 57.3 bc | 48.3 ± 13.0 ab | 0.68 ± 0.04 bcd | 0.81 ± 0.21 ab | 948.9 ± 442 de | 977.3 ± 219 a |

| Hu | 197.3 ± 8.1 cd | 41.4 ± 2.5 bc | 0.67 ± 0.02 cd | 0.69 ± 0.06 bc | 2172.5 ± 44 b | 778.0 ± 44 b |

| Sb | 108.9 ± 25.4 ef | 25.1 ± 8.2 fg | 0.73 ± 0.05 ab | 0.46 ± 0.18 de | 882.3 ± 59 def | 323.6 ± 55 d |

| Sl | 237.5 ± 13.6 b | 46.1 ± 5.2 ab | 0.62 ± 0.04 ef | 0.71 ± 0.12 b | 956.1 ± 74 de | 1177.1 ± 63 a |

| Sla | 212.7 ± 8.6 bcd | 46.7 ± 2.5 ab | 0.70 ± 0.02 bc | 0.82 ± 0.05 ab | 1529.9 ± 285 c | 982.0 ± 76 a |

| Ss | 87.8 ± 6.4 f | 21.0 ± 1.7 g | 0.76 ± 0.08 a | 0.40 ± 0.07 ef | 462.6 ± 52 gh | 318.6 ± 34 d |

| St | 144.0 ± 11.7 e | 28.4 ± 2.1 ef | 0.63 ± 0.06 de | 0.45 ± 0.07 e | 799.9 ± 70 defg | 419.1 ± 52 cd |

| CK | 233.1 ± 54.1 bc | 48.5 ± 7.8 ab | 0.68 ± 0.07 bcd | 0.81 ± 0.07 ab | 1179.4 ± 163 cd | 1073.4 ± 143 a |

| Cc | 186.4 ± 15.0 d | 36.9 ± 2.4 cd | 0.63 ± 0.03 de | 0.58 ± 0.03 cd | 559.9 ± 36 efgh | 740.1 ± 41 b |

| Es | 275.3 ± 29.8 a | 50.2 ± 5.0 a | 0.58 ± 0.03 efg | 0.73 ± 0.07 ab | 4086.0 ± 167 a | 1095.1 ± 49 a |

| Gc | 129.7 ± 31.8 e | 22.2 ± 6.0f g | 0.55 ± 0.01 g | 0.30 ± 0.08 f | 390.9 ± 62 h | 466.6 ± 67 cd |

| Pc | 236.6 ± 9.1 b | 50.4 ± 2.9 a | 0.68 ± 0.02 bcd | 0.86 ± 0.06 a | 1476.3 ± 127 c | 1082.5 ± 139 a |

| Pm | 180.0 ± 14.9 d | 32.7 ± 4.4 de | 0.57 ± 0.04 fg | 0.48 ± 0.10 de | 538.8 ± 120 fgh | 598.8 ± 71 bc |

| F | 21.31 | 24.69 | 13.59 | 21.80 | 61.24 | 22.78 |

| Sig. | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Strains | Chlorophyll A (mg/kg) | Chlorophyll B (mg/kg) | Chlorophyll A/B | Carotenoids (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Av | 1.18 ± 0.04 a | 0.33 ± 0.01 a | 3.55 ± 0.01 f | 0.21 ± 0.009 a |

| Hu | 0.84 ± 0.02 f | 0.23 ± 0.01 f | 3.71 ± 0.04 de | 0.17 ± 0.001 cde |

| Sb | 0.99 ± 0.01 d | 0.27 ± 0.005 cd | 3.61 ± 0.02 ef | 0.19 ± 0.003 b |

| Sl | 0.87 ± 0.01 f | 0.20 ± 0.001 g | 4.23 ± 0.04a | 0.17 ± 0.005 cde |

| Sla | 1.05 ± 0.03 c | 0.26 ± 0.01 d | 4.02 ± 0.251 b | 0.16 ± 0.009 e |

| Ss | 1.01 ± 0.04 cd | 0.24 ± 0.02 ef | 4.26 ± 0.15 a | 0.19 ± 0.013 b |

| St | 1.03 ± 0.03 cd | 0.28 ± 0.01 c | 3.68 ± 0.03 ef | 0.20 ± 0.003 a |

| CK | 0.71 ± 0.07 g | 0.17 ± 0.02 h | 4.12 ± 0.16 ab | 0.17 ± 0.007 c |

| Cc | 1.13 ± 0.03 b | 0.30 ± 0.01 b | 3.73 ± 0.002 de | 0.21 ± 0.001 a |

| Es | 0.92 ± 0.05 e | 0.23 ± 0.02 f | 4.10 ± 0.06 b | 0.16 ± 0.013 de |

| Gc | 1.05 ± 0.03 c | 0.27 ± 0.01 cd | 3.90 ± 0.05 c | 0.21 ± 0.007 a |

| Pc | 1.04 ± 0.04 c | 0.27 ± 0.01 cd | 3.82 ± 0.03 cd | 0.17 ± 0.011 cd |

| Pm | 0.88 ± 0.02 ef | 0.24 ± 0.01 e | 3.61 ± 0.10 ef | 0.18 ± 0.004 bc |

| F | 61.44 | 60.68 | 34.13 | 30.06 |

| Sig. | ** | ** | ** | ** |

| Root Morphology | Root length | Root Surface Area | R/S Ratio | Root Activity | Avg. Root Diameter | Root Volume | No. of Root Tips | No. of Root Forks | Diameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | −0.418 | −0.411 | 0.311 | −0.175 | 0.133 | −0.379 | −0.325 | −0.483 | −0.126 |

| Morbidity | −0.591 * | −0.590 * | 0.064 | −0.103 | 0.109 | −0.552 | −0.505 | −0.655* | −0.074 |

| Physiology parameters | Chorophyll A | Chorophyll B | Carotenoids | A/B | Dryweight | Water Content | Height | Diameter | Fresh Weight |

| Mortality | 0.008 | 0.169 | 0.491 | −0.409 | −0.360 | −0.564 * | −0.363 | −0.126 | −0.369 |

| Morbidity | 0.135 | 0.310 | 0.642 * | −0.529 | −0.176 | −0.375 | −0.455 | −0.074 | −0.136 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chu, H.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Tang, M. The Dark Septate Endophytes and Ectomycorrhizal Fungi Effect on Pinus tabulaeformis Carr. Seedling Growth and their Potential Effects to Pine Wilt Disease Resistance. Forests 2019, 10, 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10020140

Chu H, Wang C, Li Z, Wang H, Xiao Y, Chen J, Tang M. The Dark Septate Endophytes and Ectomycorrhizal Fungi Effect on Pinus tabulaeformis Carr. Seedling Growth and their Potential Effects to Pine Wilt Disease Resistance. Forests. 2019; 10(2):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10020140

Chicago/Turabian StyleChu, Honglong, Chunyan Wang, Zhumei Li, Haihua Wang, Yuguo Xiao, Jie Chen, and Ming Tang. 2019. "The Dark Septate Endophytes and Ectomycorrhizal Fungi Effect on Pinus tabulaeformis Carr. Seedling Growth and their Potential Effects to Pine Wilt Disease Resistance" Forests 10, no. 2: 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10020140

APA StyleChu, H., Wang, C., Li, Z., Wang, H., Xiao, Y., Chen, J., & Tang, M. (2019). The Dark Septate Endophytes and Ectomycorrhizal Fungi Effect on Pinus tabulaeformis Carr. Seedling Growth and their Potential Effects to Pine Wilt Disease Resistance. Forests, 10(2), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10020140