Open Problems in Universal Induction & Intelligence

Abstract

:“The mathematician is by now accustomed to intractable equations, and even to unsolved problems, in many parts of his discipline. However, it is still a matter of some fascination to realize that there are parts of mathematics where the very construction of a precise mathematical statement of a verbal problem is itself a problem of major difficulty.”—Richard Bellman, Adaptive Control Processes (1961) p.194

1. Introduction

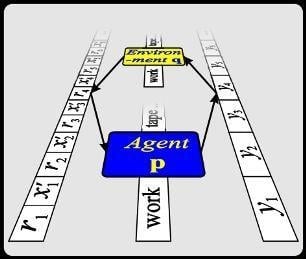

2. Universal Artificial Intelligence

3. History and State-of-the-Art

- (1)

- The major basis is Algorithmic information theory [41], initiated by [37,38,57], which builds the foundation of complexity and randomness of individual objects. It can be used to quantify Occam’s razor principle (use the simplest theory consistent with the data). This in turn allowed Solomonoff to come up with a universal theory of induction [37,50].

- (2)

4. Open Problems in Universal Induction

- a)

- The zero prior problem. The problem is how to confirm universal hypotheses like “all balls in some urn (or all ravens) are black”. A natural model is to assume that balls (or ravens) are drawn randomly from an infinite population with fraction θ of black balls (or ravens) and to assume some prior density over (a uniform density gives the Bayes-Laplace model). Now we draw n objects and observe that they are all black. The problem is that the posterior proability , since the prior probability . Maher’s [143] approach does not solve the problem [31].

- b)

- The black raven paradox by Carl Gustav Hempel goes as follows [144, Ch.11.4]: Observing Black Ravens confirms the hypothesis H that all ravens are black. In general, hypothesis is confirmed by R-instances with property B. Formally substituting and leads to hypothesis is confirmed by -instances with property . But since and are logically equivalent, must also be confirmed by -instance with property . Hence by , observing Black Ravens confirms Hypothesis H, so by , observing White Socks also confirms that all Ravens are Black, since White Socks are non-Ravens which are non-Black. But this conclusion is absurd. Again, neither Maher’s nor any other approach solves this problem.

- c)

- The Grue problem [145]. Consider the following two hypotheses: “All emeralds are green”, and “All emeralds found till year 2020 are green, thereafter all emeralds are blue”. Both hypotheses are equally well supported by empirical evidence. Occam’s razor seems to favor the more plausible hypothesis , but by using new predicates grue:=“green till y2020 and blue thereafter” and bleen:=“blue till y2020 and green thereafter”, gets simpler than .

- d)

- Reparametrization invariance [146]. The question is how to extend the symmetry principle from finite hypothesis classes (all hypotheses are equally likely) to infinite hypothesis classes. For “compact” classes, Jeffrey’s prior [147] is a solution, but for non-compact spaces like or , classical statistical principles lead to improper distributions, which are often not acceptable.

- e)

- Old-evidence/updating problem and ad-hoc hypotheses [148]. How shall a Bayesian treat the case when some evidence (e.g. Mercury’s perihelion advance) is known well-before the correct hypothesis/theory/model (Einstein’s general relativity theory) is found? How shall H be added to the Bayesian machinery a posteriori? What is the prior of H? Should it be the belief in H in a hypothetical counterfactual world in which E is not known? Can old evidence E confirm H? After all, H could simply be constructed/biased/fitted towards “explaining” E. Strictly speaking, a Bayesian needs to choose the hypothesis/model class before seeing the data, which seldom reflects scientific practice [5].

- f)

- g)

- Prediction of selected bits. Consider a very simple and special case of problem 5.i, a binary sequence that coincides at even times with the preceding (odd) bit, but is otherwise incomputable. Every child will quickly realize that the even bits coincide with the preceding odd bit, and after a while perfectly predict the even bits, given the past bits. The incomputability of the sequence is no hindrance. It is unknown whether Solomonoff works or fails in this situation. I expect that a solution of this special case will lead to general useful insights and advance this theory (cf. problem 5.i).

- h)

- Identification of “natural” Turing machines. In order to pin down the additive/multiplicative constants that plague most results in AIT, it would be highly desirable to identify a class of “natural” UTMs/USMs which have a variety of favorable properties. A more moderate approach may be to consider classes of universal Turing machines (UTM) or universal semimeasures (USM) satisfying certain properties and showing that the intersection is not empty. Indeed, very occasionally results in AIT only hold for particular (subclasses of) UTMs [153]. A grander vision is to find the single “best” UTM or USM [154] (a remarkable approach).

- i)

- Martin-Löf convergence. Quite unexpectedly, a loophole in the proof of Martin-Löf (M.L.) convergence of M to μ in the literature has been found [101]. In [102] it has been shown that this loophole cannot be fixed, since M.L.-convergence actually can fail. The construction of non-universal (semi)measures D and W that M.L. converge to μ [103] partially rescued the situation. The major problem left open is the convergence rate for . The current bound for is double exponentially worse than for . It is also unknown whether convergence in ratio holds. Finally, there could still exist universal semimeasures M (dominating all enumerable semimeasures) for which M.L.-convergence holds. In case they exist, they probably have particularly interesting additional structure and properties.

- j)

- Generalized mixtures and convergence concepts. Another interesting and potentially fruitful approach to the above convergence problem is to consider other classes of semimeasures [63,66,86], define mixtures ξ over , and (possibly) generalized randomness concepts by using this ξ to define a generalized notion of randomness. Using this approach, in [87] it has been shown that convergence holds for a subclass of Bernoulli distributions if the class is dense, but fails if the class is gappy, showing that a denseness characterization of could be promising in general. See also [155,156].

- k)

- Lower convergence bounds and defect of M. One can show that , i.e. the probability of making a wrong prediction converges to zero slower than any computable summable function. This shows that, although M converges rapidly to μ in a cumulative sense, occasionally, namely for simply describable t, the prediction quality is poor. An easy way to show the lower bound is to exploit the semimeasure defect of M. Do similar lower bounds hold for a proper (Solomonoff) normalized measure ? I conjecture the answer is yes, i.e. the lower bound is not a semimeasure artifact, but “real”.

- l)

- Using AIXI for prediction. Since AIXI is a unification of sequential decision theory with the idea of universal probability one may think that the AIXI model for a sequence prediction problem exactly reduces to Solomonoff’s universal sequence prediction scheme. Unfortunately this is not the case. For one reason, M is only a probability distribution on the inputs but not on the outputs. This is also one of the origins of the difficulty of proving general value bounds for AIXI. The questions is whether, nevertheless, AIXI predicts sequences as well as Solomonoff’s scheme. A first weak bound in a very restricted setting has been proven in [27, Sec.6.2], showing that progress in this question is possible.

5. Open Problems regarding Optimality of AIXI

- a)

- What is meant by universal optimality? A “learner” (like AIXI) may converge to the optimal informed decision maker (like AIμ) in several senses. Possibly relevant concepts from statistics are, consistency, self-tuningness, self-optimizingness, efficiency, unbiasedness, asymptotically or finite convergence [109], Pareto-optimality, and some more defined in [27]. Some concepts are stronger than necessary, others are weaker than desirable but suitable to start with. It is necessary to investigate in more breadth which properties the AIXI model satisfies.

- b)

- Limited environmental classes. The problem of defining and proving general value bounds becomes more feasible by considering, in a first step, restricted concept classes. One could analyze AIXI for known classes (like Markov or factorizable environments) and especially for the new classes (forgetful, relevant, asymptotically learnable, farsighted, uniform, and (pseudo-)passive) defined in [27].

- c)

- Generaliztion of AIXI to general Bayes mixtures. Alternatively one can generalize AIXI to AIξ, where is a general Bayes-mixture of distributions ν in some class and prior . If is the multi-set of all enumerable semi-measures, then AIξ coincides with AIXI. If is the (multi)set of passive semi-computable environments, then AIXI reduces to Solomonoff’s optimal predictor [18]. The key is not to prove absolute results for specific problem classes, but to prove relative results of the form “if there exists a policy with certain desirable properties, then AIξ also possesses these desirable properties”. If there are tasks which cannot be solved by any policy, AIξ should not be blamed for failing.

- d)

- Intelligence Aspects of AIXI. Intelligence can have many faces. As argued in [27], it is plausible that AIXI possesses all or at least most properties an intelligent rational agent should posses. Some of the following properties could and should be investigated mathematically: creativity, problem solving, pattern recognition, classification, learning, induction, deduction, building analogies, optimization, surviving in an environment, language processing, planning.

- f)

- Posterior convergence for unbounded horizon. Convergence of M to μ holds somewhat surprisingly even for unbounded horizon, which is good news for AIXI. Unfortunately convergence can be slow, but I expect that convergence is “reasonably” fast for “slowly” growing horizon, which is important in AIXI. It would be useful to quantify and prove such a result.

- g)

- Reinforcement learning. Although there is no explicit learning algorithm built into the AIXI model, AIXI is a reinforcement learning system capable of receiving and exploiting rewards. The system learns by eliminating Turing machines q in the definition of M once they become inconsistent with the progressing history. This is similar to Gold-style learning [157]. For Markov environments (but not for partially observable environments) there are efficient general reinforcement learning algorithms, like and Q learning. One could compare the performance (learning speed and quality) of AIξ to e.g. and Q learning, extending [52].

- h)

- Posterization. Many properties of Kolmogorov complexity, Solomonoff’s prior, and reinforcement learning algorithms remain valid after “posterization”. With posterization I mean replacing the total value , the weights , the complexity , the environment , etc. by their “posteriors” , , , , etc, where k is the current cycle and m the lifespan of AIXI. Strangely enough for chosen as it is not true that . If this property were true, weak bounds as the one proven in [27, Sec.6.2] (which is too weak to be of practical importance) could be boosted to practical bounds of order 1. Hence, it is highly import to rescue the posterization property in some way. It may be valid when grouping together essentially equal distributions ν.

- i)

- Relevant and non-computable environments μ. Assume that the observations of AIXI contain irrelevant information, like noise. Irrelevance can formally be defined as being statistically independent of future observations and rewards, i.e. neither affecting rewards, nor containing information about future observations. It is easy to see that Solomonoff prediction does not decline under such noise if it is sampled from a computable distribution. This likely transfers to AIXI. More interesting is the case, where the irrelevant input is complex. If it is easily separable from the useful input it should not affect AIXI. One the other hand, even in prediction this problem is non-trivial, see problem 4.g. How robustly does AIXI deal with complex but irrelevant inputs? A model that explicitly deals with this situation has been developed in [129,130].

- j)

- Grain of truth problem [158]. Assume AIXI is used in a multi-agent setup [159] interacting with other agents. For simplicity I only discuss the case of a single other agent in a competitive setup, i.e. a two-person zero-sum game situation. We can entangle agents A and B by letting A observe B’s actions and vice versa. The rewards are provided externally by the rules of the game. The situation where A is AIXI and B is a perfect minimax player was analyzed in [27, Sec.6.3]. In multi-agent systems one is mostly interested in a symmetric setup, i.e. B is also an AIXI. Whereas both AIXIs may be able to learn the game and improve their strategies (to optimal minimax or more generally Nash equilibrium), this setup violates one of the basic assumptions. Since AIXI is incomputable, AIXI(B) does not constitute a computable environment for AIXI(A). More generally, starting with any class of environments , then AI seems not to belong to class for most (all?) choices of . Various results can no longer be applied, since when coupling two AIξs. Many questions arise: Are there interesting environmental classes for which AI or AI? Do AIXI() converge to optimal minimax players? Do AIXIs perform well in general multi-agent setups?

6. Open Problems regarding Uniqueness of AIXI

- a)

- Action with expert advice. Expected performance bounds for predictions based on Solomonoff’s prior exist. Inspired by Solomonoff induction, a dual, currently very popular approach, is “prediction with expert advice” (PEA) [11,160,161]. Whereas PEA performs well in any environment, but only relative to a given set of experts, Solomonoff’s predictor competes with any other predictor, but only in expectation for environments with computable distribution. It seems philosophically less compromising to make assumptions on prediction strategies than on the environment, however weak. PEA has been generalized to active learning [11,162], but the full reinforcement learning case is still open [52]. If successful, it could result in a model dual to AIXI, but I expect the answer to be negative, which on the positive side would show the distinguishedness of AIXI. Other ad-hoc approaches like [126,163] are also unlikely to be competitive.

- b)

- Actions as random variables. There may be more than one way for the choice of the generalized M in the AIXI model. For instance, instead of defining M as in [27] one could treat the agent’s actions a also as universally distributed random variables and then conditionalize M on a.

- c)

- Structure of AIXI. The algebraic properties and the structure of AIXI has barely been investigated. It is known that the value of AIμ is a linear function in μ and the value of AIXI is a convex function in μ, but this is neither very deep nor very specific to AIXI. It should be possible to extract all essentials from AIXI which finally should lead to an axiomatic characterization of AIXI. The benefit is as in any axiomatic approach: It would clearly exhibit the assumptions, separate the essentials from technicalities, simplify understanding and, most importantly, guide in finding proofs.

- d)

- Parameter dependence. The AIXI model depends on a few parameters: the choice of observation and action spaces and , the horizon m, and the universal machine U. So strictly speaking, AIXI is only (essentially) unique, if it is (essentially) independent of the parameters. I expect this to be true, but it has not been proven yet. The U-dependence has been discussed in problem 4.h. Countably infinite and would provide a rich enough interface for all problems, but even binary and are sufficient by sequentializing complex observations and actions. For special classes one could choose [20]; unfortunately, the universal environment M does not belong to any of these special classes. See [27,32,164] for some preliminary considerations.

7. Open Problems in Defining Intelligence

- a)

- General and specific performance measures. Currently it is only partially understood how the IOR theoretically compares to the myriad of other tests of intelligence such as conventional IQ tests or even other performance tests proposed by AI other researchers. Another open question is whether the IOR might in some sense be too general. One may narrow the IOR to specific classes of problems [139] and compare how the resulting IOR measures compare to standard performance measures for each problem class. This could shed light on aspects of the IOR and possibly also establish connections between seemingly unrelated performance metrics for different classes of problems.

- b)

- Practical performance measures. A more practically orientated line of investigation would be to produce a resource bounded version of the IOR like the one in [27, Sec.7], or perhaps some of its special cases. This would allow one to define a practically implementable performance test, similar to the way in which the C-Test has been derived from incomputable definitions of compression using complexity [175]. As there are many subtle kinds of resource bounded complexity [41], the advantages and disadvantages of each in this context would need to be carefully examined. Another possibility is the recent Speed Prior [63] or variants of this approach.

- c)

- Experimental evaluation. Once a computable version of the IOR had been defined, one could write a computer program that implements it. One could then experimentally explore its characteristics in a range of different problem spaces. For example, it might be possible to find correlations with IQ test scores when applied to humans, like has been done with the C-Test [174]. Another possibility would be to consider more limited domains like classification problems or sequence prediction problems and to see whether the relative performance of algorithms according to the IOR agrees with standard performance measures and real world performance.

8. Conclusions

- Problems roughly sorted from most important or interesting to least:5.j,4.h,7.b,5.a,7.c,4.b,4.f,4.l,5.d,5.f,5.i,4.a,4.c,4.d,4.e,4.g,5.c,6.a,6.b,5.g,5.h,4.j,5.b,6.c,7.a,4.i,4.k,6.d.

- Problems roughly sorted from most to least time consuming:4.b,4.h,5.d,5.j,7.c,4.c,5.b,5.c,6.c,6.a,5.g,5.i,7.b,4.i,4.j,4.l,5.a,6.d,6.b,5.f,5.h,4.d,4.f,4.g,4.k,7.a,4.a,4.e.

- Problems roughly sorted from hard to easy:4.h,6.c,5.j,4.b,4.i,4.l,5.b,6.a,7.b,4.c,4.g,5.a,5.c,6.b,5.f,5.i,4.j,5.h,7.a,4.d,4.f,4.k,5.d,6.d,7.c,4.a,4.e,5.g.

References and Notes

- Hume, D. A Treatise of Human Nature, Book I. [Edited version by L. A. Selby-Bigge and P. H. Nidditch, Oxford University Press, 1978; 1739.

- Popper, K.R. Logik der Forschung; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1934. [Google Scholar] [English translation: The Logic of Scientific Discovery Basic Books, New York, NY, USA, 1959, and Hutchinson, London, UK, revised edition, 1968.

- Howson, C. Hume’s Problem: Induction and the Justification of Belief, 2nd Ed. ed; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, I. Gambling with Truth: An Essay on Induction and the Aims of Science; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Earman, J. Bayes or Bust? A Critical Examination of Bayesian Confirmation Theory; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, C.S. Statistical and Inductive Inference by Minimum Message Length; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, W.C. Four Decades of Scientific Explanation; University of Pittsburgh Press: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Frigg, R.; Hartmann, S. Models in science. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2006. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/models-science/.

- Wikipedia. Predictive modelling. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brockwell, P.J.; Davis, R.A. Introduction to Time Series and Forecasting, 2nd Ed. ed; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cesa-Bianchi, N.; Lugosi, G. Prediction, Learning, and Games; Cambridge University Press: Cambrige, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Geisser, S. Predictive Inference; Chapman & Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield, C. The Analysis of Time Series: An Introduction, 6th Ed. ed; Chapman & Hall / CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, T.S. Mathematical Statistics: A Decision Theoretic Approach, 3rd Ed. ed; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- DeGroot, M.H. Optimal Statistical Decisions; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, R.C. The Logic of Decision, 2nd Ed. ed; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, J.B. The Uncertain Reasoner’s Companion: A Mathematical Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. Optimality of universal Bayesian prediction for general loss and alphabet. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2003, 4, 971–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. Universal algorithmic intelligence: A mathematical top→down approach, In Artificial General Intelligence; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 227–290. [Google Scholar]

- Bertsekas, D.P. Dynamic Programming and Optimal Control, volume I and II, 3rd Ed. ed; Athena Scientific: Belmont, MA, USA, 2006; Volumes 1 and 2. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, S. Toward a monistic theory of science: The ‘strong programme’ reconsidered. Philosophy of the Social Sciences 2003, 33, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.H.; Longino, H.E.; Waters, C.K. (Eds.) Scientific Pluralism; Univ. of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2006.

- Green, M.B.; Schwarz, J.H.; Witten, E. Superstring Theory: Volumes 1 and 2; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, B. The Elegant Universe: Superstrings, Hidden Dimensions, and the Quest for the Ultimate Theory; Vintage Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, S.J.; Norvig, P. Artificial Intelligence. A Modern Approach, 2nd Ed. ed; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. A theory of universal artificial intelligence based on algorithmic complexity. Technical Report cs.AI/0004001, München, Germany, 62 pages, 2000. http://arxiv.org/abs/cs.AI/0004001.

- Hutter, M. Universal Artificial Intelligence: Sequential Decisions based on Algorithmic Probability; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005; 300 pages, http://www.hutter1.net/ai/uaibook.htm.

- Oates, T.; Chong, W. Book review: Marcus Hutter, universal artificial intelligence, Springer (2004). Artificial Intelligence 2006, 170, 1222–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomonoff, R.J. A preliminary report on a general theory of inductive inference. Technical Report V-131; Zator Co.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar] Distributed at the Conference on Cerebral Systems and Computers, 8–11 Feb. 1960.

- Bellman, R.E. Dynamic Programming; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. On universal prediction and Bayesian confirmation. Theoretical Computer Science 2007, 384, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, S.; Hutter, M. Universal intelligence: A definition of machine intelligence. Minds & Machines 2007, 17, 391–444. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J. The Science of Conjecture: Evidence and Probability before Pascal; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Asmis, E. Epicurus’ Scientific Method; Cornell Univ. Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Turing, A.M. On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem. Proc. London Mathematical Society 1937, 2, 230–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayes, T. An essay towards solving a problem in the doctrine of chances. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 1763, 53, 376–398, [Reprinted in Biometrika, 45, 296–315, 1958]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomonoff, R.J. A formal theory of inductive inference: Parts 1 and 2. Information and Control 1964, 7, 1–22 and 224–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Three approaches to the quantitative definition of information. Problems of Information and Transmission 1965, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J. Statistical Decision Theory and Bayesian Analysis, 3rd Ed. ed; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. Algorithmic information theory: a brief non-technical guide to the field. Scholarpedia 2007, 2, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Vitányi, P.M.B. An Introduction to Kolmogorov Complexity and its Applications, 3rd Ed. ed; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. Algorithmic complexity. Scholarpedia 2008, 3, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D.J.C. Information theory, inference and learning algorithms; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cover, T.M.; Thomas, J.A. Elements of Information Theory, 2nd Ed. ed; Wiley-Intersience: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lempel, A.; Ziv, J. On the complexity of finite sequences. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1976, 22, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilibrasi, R.; Vitányi, P.M.B. Clustering by compression. IEEE Trans. Information Theory 2005, 51, 1523–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, F.M.J.; Shtarkov, Y.M.; Tjalkens, T.J. Reflections on the prize paper: The context-tree weighting method: Basic properties. In IEEE Information Theory Society Newsletter; 1997; pp. 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M.; Legg, S.; Vitányi, P.M.B. Algorithmic probability. Scholarpedia 2007, 2, 2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvonkin, A.K.; Levin, L.A. The complexity of finite objects and the development of the concepts of information and randomness by means of the theory of algorithms. Russian Mathematical Surveys 1970, 25, 83–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomonoff, R.J. Complexity-based induction systems: Comparisons and convergence theorems. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1978, IT-24, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Vitányi, P.M.B. Applications of algorithmic information theory. Scholarpedia 2007, 2, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, J.; Hutter, M. Universal learning of repeated matrix games. In Proc. 15th Annual Machine Learning Conf. of Belgium and The Netherlands (Benelearn’06), Ghent, Belgium, 2006; pp. 7–14.

- Pankov, S. A computational approximation to the AIXI model. In Proc. 1st Conference on Artificial General Intelligence, 2008; Vol. 171, pp. 256–267.

- Hutter, M. Universal sequential decisions in unknown environments. In Proc. 5th European Workshop on Reinforcement Learning (EWRL-5), Onderwijsinsituut CKI, Utrecht Univ., Netherlands, 2001; Vol. 27, pp. 25–26.

- Hutter, M. Towards a universal theory of artificial intelligence based on algorithmic probability and sequential decisions. In Proc. 12th European Conf. on Machine Learning (ECML’01), Freiburg, Germany, 2001; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 2167, LNAI. pp. 226–238.

- Legg, S. Machine Super Intelligence. PhD thesis, IDSIA, Lugano, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chaitin, G.J. On the length of programs for computing finite binary sequences. Journal of the ACM 1966, 13, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, J.V.; Morgenstern, O. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Löf, P. The definition of random sequences. Information and Control 1966, 9, 602–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A. Randomness conservation inequalities: Information and independence in mathematical theories. Information and Control 1984, 61, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.A. Universal sequential search problems. Problems of Information Transmission 1973, 9, 265–266. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidhuber, J. The speed prior: A new simplicity measure yielding near-optimal computable predictions. In Proc. 15th Conf. on Computational Learning Theory (COLT’02), Sydney, Australia, 2002; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 2375, LNAI. pp. 216–228.

- Chaitin, G.J. Algorithmic Information Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chaitin, G.J. The Limits of Mathematics: A Course on Information Theory and the Limits of Formal Reasoning; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidhuber, J. Hierarchies of generalized Kolmogorov complexities and nonenumerable universal measures computable in the limit. International Journal of Foundations of Computer Science 2002, 13, 587–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gács, P.; Tromp, J.; Vitányi, P.M.B. Algorithmic statistics. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2001, 47, 2443–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereshchagin, N.; Vitányi, P.M.B. Kolmogorov’s structure functions with an application to the foundations of model selection. In Proc. 43rd Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, Vancouver, Canada, 2002; pp. 751–760.

- Vitányi, P.M.B. Meaningful information. Proc. 13th International Symposium on Algorithms and Computation (ISAAC’02) 2002, 2518, 588–599. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, C.S.; Boulton, D.M. An information measure for classification. Computer Journal 1968, 11, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, J.J. Modeling by shortest data description. Automatica 1978, 14, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissanen, J.J. Stochastic Complexity in Statistical Inquiry; World Scientific: Singapore, Singapore, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, J.R.; Rivest, R.L. Inferring decision trees using the minimum description length principle. Information and Computation 1989, 80, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Li, M. The minimum description length principle and its application to online learning of handprinted characters. In Proc. 11th International Joint Conf. on Artificial Intelligence, Detroit, MI, USA, 1989; pp. 843–848.

- Milosavljevic̀, A.; Jurka, J. Discovery by minimal length encoding: A case study in molecular evolution. Machine Learning 1993, 12, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pednault, E.P.D. Some experiments in applying inductive inference principles to surface reconstruction. In Proc. 11th International Joint Conf. on Artificial Intelligence, San Mateo, CA, USA, 1989; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA; pp. 1603–1609.

- Grünwald, P.D. The Minimum Description Length Principle; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cilibrasi, R.; Vitányi, P.M.B. Similarity of objects and the meaning of words. In Proc. 3rd Annual Conferene on Theory and Applications of Models of Computation (TAMC’06), Beijing, China, 2006; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 3959, LNCS. pp. 21–45.

- Schmidhuber, J. Discovering neural nets with low Kolmogorov complexity and high generalization capability. Neural Networks 1997, 10, 857–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J.; Zhao, J.; Wiering, M.A. Shifting inductive bias with success-story algorithm, adaptive Levin search, and incremental self-improvement. Machine Learning 1997, 28, 105–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J. Optimal ordered problem solver. Machine Learning 2004, 54, 211–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J. Low-complexity art. Leonardo, Journal of the International Society for the Arts, Sciences, and Technology 1997, 30, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calude, C.S. Information and Randomness: An Algorithmic Perspective, 2nd Ed. ed; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. The fastest and shortest algorithm for all well-defined problems. International Journal of Foundations of Computer Science 2002, 13, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stork, D. Foundations of Occam’s razor and parsimony in learning. NIPS 2001 Workshop. 2001. http://www.rii.ricoh.com/∼stork/OccamWorkshop.html.

- Hutter, M. On the existence and convergence of computable universal priors. In Proc. 14th International Conf. on Algorithmic Learning Theory (ALT’03), Sapporo, Japan, 2003; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 2842, LNAI. pp. 298–312.

- Hutter, M. On generalized computable universal priors and their convergence. Theoretical Computer Science 2006, 364, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, M. Convergence and error bounds for universal prediction of nonbinary sequences. In Proc. 12th European Conf. on Machine Learning (ECML’01), Freiburg, Germany, 2001; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001; Vol. 2167, LNAI. pp. 239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. New error bounds for Solomonoff prediction. Journal of Computer and System Sciences 2001, 62, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, M. General loss bounds for universal sequence prediction. In Proc. 18th International Conf. on Machine Learning (ICML’01), Williams College, Williamstown, MA, USA, 2001; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA; pp. 210–217.

- Hutter, M. Convergence and loss bounds for Bayesian sequence prediction. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2003, 49, 2061–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, M. Online prediction – Bayes versus experts. Technical report, http://www.hutter1.net/ai/bayespea.htm 2004. Presented at the EU PASCAL Workshop on Learning Theoretic and Bayesian Inductive Principles (LTBIP’04).

- Chernov, A.; Hutter, M. Monotone conditional complexity bounds on future prediction errors. In Proc. 16th International Conf. on Algorithmic Learning Theory (ALT’05), Singapore, 2005; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 3734, LNAI. pp. 414–428.

- Chernov, A.; Hutter, M.; Schmidhuber, J. Algorithmic complexity bounds on future prediction errors. Information and Computation 2007, 205, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, M. Sequence prediction based on monotone complexity. In Proc. 16th Annual Conf. on Learning Theory (COLT’03), Washington, DC, USA, 2003; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 2777, LNAI. pp. 506–521.

- Hutter, M. Sequential predictions based on algorithmic complexity. Journal of Computer and System Sciences 2006, 72, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, J.; Hutter, M. Convergence of discrete MDL for sequential prediction. In Proc. 17th Annual Conf. on Learning Theory (COLT’04), Banff, Canada, 2004; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 3120, LNAI. pp. 300–314.

- Poland, J.; Hutter, M. Asymptotics of discrete MDL for online prediction. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2005, 51, 3780–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, J.; Hutter, M. On the convergence speed of MDL predictions for Bernoulli sequences. In Proc. 15th International Conf. on Algorithmic Learning Theory (ALT’04), Padova, Italy, 2004; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 3244, LNAI. pp. 294–308.

- Poland, J.; Hutter, M. MDL convergence speed for Bernoulli sequences. Statistics and Computing 2006, 16, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, M. An open problem regarding the convergence of universal a priori probability. In Proc. 16th Annual Conf. on Learning Theory (COLT’03), Washington, DC, USA, 2003; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 2777, LNAI. pp. 738–740.

- Hutter, M.; Muchnik, A.A. Universal convergence of semimeasures on individual random sequences. In Proc. 15th International Conf. on Algorithmic Learning Theory (ALT’04), Padova, Italy, 2004; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 3244, LNAI. pp. 234–248.

- Hutter, M.; Muchnik, A.A. On semimeasures predicting Martin-Löf random sequences. Theoretical Computer Science 2007, 382, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutter, M. On the foundations of universal sequence prediction. In Proc. 3rd Annual Conference on Theory and Applications of Models of Computation (TAMC’06), Beijing, China, 2006; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 3959, LNCS. pp. 408–420.

- Michie, D. Game-playing and game-learning automata, In Advances in Programming and Non-Numerical Computation; Pergamon: New York, NY, USA, 1966; pp. 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, D.A.; Fristedt, B. Bandit Problems: Sequential Allocation of Experiments; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Duff, M. Optimal Learning: Computational procedures for Bayes-adaptive Markov decision processes. PhD thesis, Department of Computer Science, University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Szita, I.; Lörincz, A. The many faces of optimism: a unifying approach. In Proc. 12th International Conference (ICML 2008), 2008; Helsinki, Finland; Vol. 307.

- Kumar, P.R.; Varaiya, P.P. Stochastic Systems: Estimation, Identification, and Adaptive Control; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, R.; Teneketzis, D.; Anantharam, V. Asymptotically efficient adaptive allocation schemes for controlled i.i.d. processes: Finite parameter space. IEEE Trans. Automatic Control 1989, 34, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Teneketzis, D.; Anantharam, V. Asymptotically efficient adaptive allocation schemes for controlled Markov chains: Finite parameter space. IEEE Trans. Automatic Control 1989, 34, 1249–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, A.L. Some studies in machine learning using the game of checkers. IBM Journal on Research and Development 1959, 3, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barto, A.G.; Sutton, R.S.; Anderson, C.W. Neuronlike adaptive elements that can solve difficult learning control problems. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics 1983, 834, 834–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S. Learning to predict by the methods of temporal differences. Machine Learning 1988, 3, 9–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, C. Learning from Delayed Rewards. PhD thesis, King’s College, Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, C.; Dayan, P. Q-learning. Machine Learning 1992, 8, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, A.W.; Atkeson, C.G. Prioritized sweeping: Reinforcement learning with less data and less time. Machine Learning 1993, 13, 103–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesauro, G. “TD”-Gammon, a self-teaching backgammon program, achieves master-level play. Neural Computation 1994, 6, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiering, M.A.; Schmidhuber, J. Fast online “Q”(λ). Machine Learning 1998, 33, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, M.; Koller, D. Efficient reinforcement learning in factored MDPs. In Proc. 16th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-99), Stockholm, Sweden, 1999; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA; pp. 740–747.

- Wiering, M.A.; Salustowicz, R.P.; Schmidhuber, J. Reinforcement learning soccer teams with incomplete world models. Artificial Neural Networks for Robot Learning. Special issue of Autonomous Robots 1999, 7, 77–88. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, E.B. Toward a model of intelligence as an economy of agents. Machine Learning 1999, 35, 155–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; Parr, R. Policy iteration for factored MDPs. In Proc. 16th Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (UAI-00), Stanford University, Stanford, CA, USA, 2000; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA; pp. 326–334.

- Singh, S.; Littman, M.; Jong, N.; Pardoe, D.; Stone, P. Learning predictive state representations. In Proc. 20th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML’03), Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 712–719.

- Guestrin, C.; Koller, D.; Parr, R.; Venkataraman, S. Efficient solution algorithms for factored MDPs. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research (JAIR) 2003, 19, 399–468. [Google Scholar]

- Ryabko, D.; Hutter, M. On the possibility of learning in reactive environments with arbitrary dependence. Theoretical Computer Science 2008, 405, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehl, A.L.; Diuk, C.; Littman, M.L. Efficient structure learning in factored-state MDPs. In Proc. 27th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2007; AAAI Press; pp. 645–650.

- Ross, S.; Pineau, J.; Paquet, S.; Chaib-draa, B. Online planning algorithms for POMDPs. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2008, 2008, 663–704. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. Feature Markov decision processes. In Proc. 2nd Conf. on Artificial General Intelligence (AGI’09), Arlington, VA, USA, 2009; Atlantis Press; Vol. 8, pp. 61–66.

- Hutter, M. Feature dynamic Bayesian networks. In Proc. 2nd Conf. on Artificial General Intelligence (AGI’09), Arlington, VA, USA, 2009; Atlantis Press; Vol. 8, pp. 67–73.

- Kaelbling, L.P.; Littman, M.L.; Moore, A.W. Reinforcement learning: a survey. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 1996, 4, 237–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kaelbling, L.P.; Littman, M.L.; Cassandra, A.R. Planning and acting in partially observable stochastic domains. Artificial Intelligence 1998, 101, 99–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutilier, C.; Dean, T.; Hanks, S. Decision-theoretic planning: Structural assumptions and computational leverage. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 1999, 11, 1–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, A.Y.; Coates, A.; Diel, M.; Ganapathi, V.; Schulte, J.; Tse, B.; Berger, E.; Liang, E. Autonomous inverted helicopter flight via reinforcement learning. In ISER; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2004; Vol. 21, Springer Tracts in Advanced Robotics; pp. 363–372. [Google Scholar]

- Bertsekas, D.P.; Tsitsiklis, J.N. Neuro-Dynamic Programming; Athena Scientific: Belmont, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. Bayes optimal agents in general environments. Technical report, Istituto Dalle Molle di Studi sull’Intelligenza Artificiale (IDSIA). 2004; unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, M. Self-optimizing and Pareto-optimal policies in general environments based on Bayes-mixtures. In Proc. 15th Annual Conf. on Computational Learning Theory (COLT’02), Sydney, Australia, 2002; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 2375, LNAI. pp. 364–379.

- Legg, S.; Hutter, M. Ergodic MDPs admit self-optimising policies. Technical Report IDSIA-21-04, IDSIA. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Legg, S.; Hutter, M. A taxonomy for abstract environments. Technical Report IDSIA-20-04, IDSIA. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gaglio, M. Universal search. Scholarpedia 2007, 2, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidhuber, J. Gödel machines: Self-referential universal problem solvers making provably optimal self-improvements. In Artificial General Intelligence; Springer in press. , 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes, E.T. Probability Theory: The Logic of Science; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, P. Probability captures the logic of scientific confirmation. In Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Science; Hitchcock, C., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; chapter 3; pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Rescher, N. Paradoxes: Their Roots, Range, and Resolution; Open Court: Lanham, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, N. Fact, Fiction, and Forecast, 4th Ed. ed; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Kass, R.E.; Wasserman, L. The selection of prior distributions by formal rules. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1996, 91, 1343–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffreys, H. An invariant form for the prior probability in estimation problems. Proc. Royal Society London 1946, Vol. Series A 186, 453–461. [Google Scholar]

- Glymour, C. Theory and Evidence; Princeton Univ. Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Carnap, R. The Continuum of Inductive Methods; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Laplace, P. Théorie analytique des probabilités; Courcier, Paris, France, 1812. [Google Scholar] [English translation by Truscott, F.W. and Emory, F.L.: A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities. Dover, 1952].

- Press, S.J. Subjective and Objective Bayesian Statistics: Principles, Models, and Applications, 2nd Ed. ed; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, M. Subjective bayesian analysis: Principles and practice. Bayesian Analysis 2006, 1, 403–420. [Google Scholar]

- Muchnik, A.A.; Positselsky, S.Y. Kolmogorov entropy in the context of computability theory. Theoretical Computer Science 2002, 271, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. Stationary algorithmic probability. TU Berlin, Berlin. Technical Report http://arXiv.org/abs/cs/0608095.

- Ryabko, D.; Hutter, M. On sequence prediction for arbitrary measures. In Proc. IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory (ISIT’07); IEEE: Nice, France, 2007; pp. 2346–2350. [Google Scholar]

- Ryabko, D.; Hutter, M. Predicting non-stationary processes. Applied Mathematics Letters 2008, 21, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, E.M. Language identification in the limit. Information and Control 1967, 10, 447–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalai, E.; Lehrer, E. Rational learning leads to Nash equilibrium. Econometrica 1993, 61, 1019–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, G. (Ed.) Multiagent Systems: A Modern Approach to Distributed Artificial Intelligence; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000.

- Littlestone, N.; Warmuth, M.K. The weighted majority algorithm. In 30th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science; IEEE: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 1989; pp. 256–261. [Google Scholar]

- Vovk, V.G. Universal forecasting algorithms. Information and Computation 1992, 96, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poland, J.; Hutter, M. Defensive universal learning with experts. In Proc. 16th International Conf. on Algorithmic Learning Theory (ALT’05), Singapore, 2005; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 3734, LNAI. pp. 356–370.

- Ryabko, D.; Hutter, M. Asymptotic learnability of reinforcement problems with arbitrary dependence. In Proc. 17th International Conf. on Algorithmic Learning Theory (ALT’06), Barcelona, Spain, 2006; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 4264, LNAI. pp. 334–347.

- Hutter, M. General discounting versus average reward. In Proc. 17th International Conf. on Algorithmic Learning Theory (ALT’06), Barcelona, Spain, 2006; Springer: Berlin, Germany; Vol. 4264, LNAI. pp. 244–258.

- Legg, S.; Hutter, M. A collection of definitions of intelligence. In Advances in Artificial General Intelligence: Concepts, Architectures and Algorithms; Goertzel, B., Wang, P., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2007; Vol. 157, Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications; pp. 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Legg, S.; Hutter, M. Tests of machine intelligence. In 50 Years of Artificial Intelligence, Monte Verita, Switzerland, 2007; Vol. 4850, LNAI. pp. 232–242.

- Turing, A.M. Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind 1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saygin, A.; Cicekli, I.; Akman, V. Turing test: 50 years later. Minds and Machines 2000, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Loebner, H. The loebner prize – the first turing test. 1990. http://www.loebner.net/Prizef/loebner-prize.html.

- Bringsjord, S.; Schimanski, B. What is artificial intelligence? psychometric ai as an answer. Proc. 18th International Joint Conf. on Artificial Intelligence 2003, 18, 887–893. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarado, N.; Adams, S.; Burbeck, S.; Latta, C. Beyond the turing test: Performance metrics for evaluating a computer simulation of the human mind. In Performance Metrics for Intelligent Systems Workshop; Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Horst, J. A native intelligence metric for artificial systems. In Performance Metrics for Intelligent Systems Workshop; Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Chaitin, G.J. Gödel’s theorem and information. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1982, 22, 941–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Orallo, J.; Minaya-Collado, N. A formal definition of intelligence based on an intensional variant of kolmogorov complexity. In International Symposium of Engineering of Intelligent Systems; 1998; pp. 146–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Orallo, J. Beyond the turing test. Journal of Logic, Language and Information 2000, 9, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Orallo, J. On the computational measurement of intelligence factors. In Performance Metrics for Intelligent Systems Workshop; Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Sanghi, P.; Dowe, D.L. A computer program capable of passing i.q. tests. In Proc. 4th ICCS International Conf. on Cognitive Science (ICCS’03), Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2003; pp. 570–575.

- Legg, S.; Hutter, M. A formal measure of machine intelligence. In Proc. 15th Annual Machine Learning Conference of Belgium and The Netherlands (Benelearn’06), Ghent, Belgium, 2006; pp. 73–80.

- Graham-Rowe, D. Spotting the bots with brains. New Scientist magazine, (13 August 2005). Vol. 2512, 27.

- Fiévet, C. Mesurer l’intelligence d’une machine. In Le Monde de l’intelligence; Mondeo publishing: Paris, France, 2005; Vol. 1, pp. 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Solso, R.L.; MacLin, O.H.; MacLin, M.K. Cognitive Psychology, 8th Ed. ed; Allyn & Bacon, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, D.J. (Ed.) Philosophy of Mind: Classical and Contemporary Readings; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002.

- Searle, J.R. Mind: A Brief Introduction; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, J.; Blakeslee, S. On Intelligence; Times Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hausser, R. Foundations of Computational Linguistics: Human-Computer Communication in Natural Language, 2nd Ed. ed; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, N. Language and Mind, 3rd Ed. ed; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.A. Introducing Anthropology: An Integrated Approach, 4th Ed. ed; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, R. Logics for Artificial Intelligence, Ellis Horwood Series in Artificial Intelligence. 1984.

- Lloyd, J.W. Foundations of Logic Programming, 2nd Ed. ed; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Tettamanzi, A.; Tomassini, M.; Jans̎sen, J. Soft Computing: Integrating Evolutionary, Neural, and Fuzzy Systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kardong, K.V. An Introduction to Biological Evolution, 2nd Ed. ed; McGraw-Hill Science/Engineering/Math: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

© 2009 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Hutter, M. Open Problems in Universal Induction & Intelligence. Algorithms 2009, 2, 879-906. https://doi.org/10.3390/a2030879

Hutter M. Open Problems in Universal Induction & Intelligence. Algorithms. 2009; 2(3):879-906. https://doi.org/10.3390/a2030879

Chicago/Turabian StyleHutter, Marcus. 2009. "Open Problems in Universal Induction & Intelligence" Algorithms 2, no. 3: 879-906. https://doi.org/10.3390/a2030879

APA StyleHutter, M. (2009). Open Problems in Universal Induction & Intelligence. Algorithms, 2(3), 879-906. https://doi.org/10.3390/a2030879