1. Introduction

Computational neuroscience and biomedical engineering are rapidly advancing the field of brain age assessment using electroencephalography (EEG). In the past, the power of the alpha and beta bands was important for analyzing EEG recordings. However, with modern machine learning and deep learning technologies, the methodological basis for extracting biologically meaningful information from EEG recordings has expanded significantly. Currently, the use of these methods allows for the modeling of various trajectories of neuropsychological development and deviations from standard maturation processes.

Age-related changes in EEG signals are recognized as a sign of structural and functional changes. They indicate rapid changes in neuropsychological development in childhood and adolescence, while in the aging process, they often indicate degeneration or compensatory plasticity.

Recent studies categorize EEG-based age prediction targets into three primary classifications: chronological age (CA), which serves as the most direct and frequently used benchmark; brain age, regarded as an indicator of neurobiological condition; and Brain Age Gap Estimation (BrainAGE), characterized as the discrepancy between predicted and actual CA, functioning as a measure of accelerated or decelerated brain aging. In newborns, the related metric, functional brain age (FBA), indicates neurodevelopmental status relative to the postmenstrual age. The difference in approaches to defining the term “age” certainly adds complexity to the use of the analysis results for further clinical application.

Despite the progress in this area, research methods vary greatly. First, there are the different states of the subjects. These states include the resting state, the sleeping state, and the cognitive task state. In addition, participants range widely in age, from infants to children, adolescents, and adults. Furthermore, data preprocessing methods vary. All these elements influence the comparison of results and attempts to reach specific conclusions. Some studies also use bias correction using external datasets. All of the above factors impose limitations on the use of the analysis results in clinical practice.

Predicting brain age based on EEG uses the following: types of features, model architectures, validation strategies, and target variable selection. This review examines how these methodological decisions affect performance, interpretability, and generalizability. We focus on which feature groups are most predictive, the variability in EEG paradigm performance, clinically meaningful brain age definitions, and methods for external validation and bias correction.

We used an analytical structure in which we broke down all these studies into understandable characteristics such as dataset characteristics, feature classification, EEG paradigms, data preprocessing methods, and target variable classifications, as well as, of course, machine learning and deep learning methods, so that the differences between them would be clear and not confusing. Special attention is paid to model validation protocols, the risk of overfitting, and the availability of code and data.

We found that convolutional neural networks (CNN) and ensemble models most frequently predicted CA. These approaches were more common than others and also showed stable results compared to other algorithms. With regard to BrainAGE, it was found that the best results for predicting it were obtained when delta, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma frequency spectrum features were used, as well as temporal characteristics such as event-related potential (ERP) amplitudes, latencies, and time-series statistics. When discussing FBA, the authors applied entropy metrics such as sample entropy, permutation entropy, spectral entropy, and others. It was found that these metrics accurately reflect the degree of maturity of brain activity in infants and help determine FBA. It should be noted that there are still few such studies, but the results are promising, and there is potential for further development in this area.

2. Materials and Methods

We did not limit our research to specific age categories in order to identify different approaches for different age segments, as well as to observe changes that occur with age and determine whether there are any patterns for modeling methods for different age groups.

Studies were deemed eligible if they used EEG as the main data source, applied machine learning (ML) or deep learning (DL) techniques for age prediction, published clear methodological documentation, and reported quantitative performance metrics such as coefficient of determination R2 and mean absolute error (MAE). Only empirical studies using supervised learning techniques were considered. We excluded studies in which the analysis was not performed on EEG data or the analysis was performed without taking EEG characteristics into account, as well as those that did not include age prediction.

The article selection process worked as follows. Two reviewers independently evaluated the studies that met the selection criteria. All disagreements were discussed, and a consensus was reached. Each study was analyzed in terms of EEG data types, preprocessing methods, population characteristics, validation methods, and the list of characteristics for these models, as well as the models themselves.

As part of our data analysis, we identified a number of characteristics, such as sample size, age range, EEG paradigm, and preprocessing methods. In the data where it was possible, we noted that the control of retraining and cross-validation methods also added geographical and demographic differences.

2.1. Literature Search and Selection Strategy

A structured search was performed in ResearchGate, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar using the following search terms and their combinations: “prediction of brain age using EEG” OR “prediction of chronological age using EEG” OR “prediction of age using EEG” OR “Brain Age Estimation using EEG” OR “BrainAGE Estimation using EEG” OR “Chronological Age Prediction using EEG”. The search returned 31,076 results: 1005 from ResearchGate, 393 from Web of Science, 86 from IEEE Xplore, 11,392 from ScienceDirect, and 19,200 from Google Scholar. The search was confined to articles published in English from 2015 onwards and was limited to original research and review articles.

We only looked at the 1000 most relevant results from each database. This strategy was adopted to ensure that no relevant studies were missed while avoiding an unmanageable screening workload, as records beyond this threshold were typically non-relevant.

For a comprehensive analysis, we included only those studies that described the methodological basis in sufficient detail and provided quantitative estimates of model predictability. Studies were excluded if they used non-EEG data or were published before 2015.

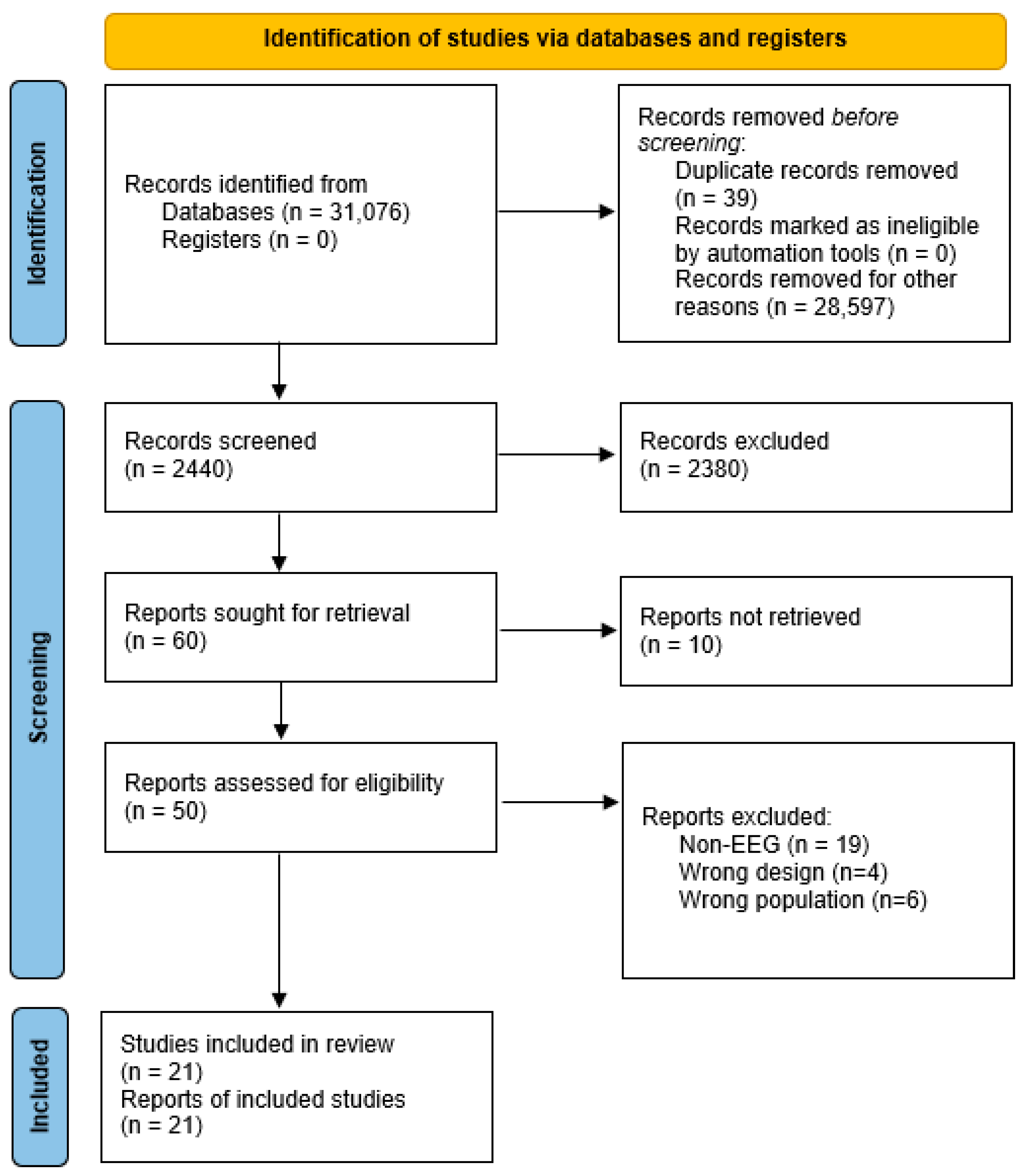

After thoroughly removing duplicates and analyzing the texts, we prepared a final set of 21 publications. The selection procedure complies with PRISMA 2020 [

1] standards, as shown in

Figure 1.

A formal risk of bias evaluation was not conducted. Potential biases were mitigated by rigorously applying inclusion and exclusion criteria. We also examined references from the analyzed works, which allowed us to compile a rigorous methodological study with a clear description of brain age prediction based on EEG.

2.2. Dataset Classification and Characteristics

In this section, EEG datasets were classified. They were structured according to the EEG paradigm and age categories of participants, and clinical statuses of the subjects were added wherever available. The classification enhances the understanding of variability in model performance and establishes a basis for benchmarking.

Table 1 categorizes studies according to EEG paradigms: resting state (including both eyes open and eyes closed), ERP, and sleep (including meditation EEG). Some studies were classified into multiple categories due to their use of multi-paradigm methods.

In

Table 2, the datasets are structured by age group, starting with newborns and adolescents and ending with adults.

The generalization of results is influenced by EEG configuration, signal duration, clinical classification, and dataset availability (

Table S1). For example, datasets such as TUH and NeuroTechX are publicly available, whilst others depend on private clinical cohorts. Channel density varies from 4 [

22] to 128 [

14]. EEG durations range from short segments [

7] to overnight recordings [

20]. The clinical state exhibits considerable variability, ranging from healthy individuals to those categorized by psychiatric or neurological conditions (e.g., Major Depressive Disorder, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and macrocephaly).

The criteria for selecting participants, their health status, gender, age, and dataset sizes are presented in

Table S1 (Supplementary Materials). All of this contributes to the transparency of the methodology. These parameters are important when assessing the reliability of the models used, as well as the possibility of generalization among different studies.

The reviewed studies represent geographic diversity, including datasets from China [

10], India [

11], South Korea [

19], Cuba [

2], and multi-ethnic cohorts from the United States such as MESA, which includes Black, White, Hispanic, and Chinese American participants [

20].

3. Results

In this chapter, we identified the main parameters that were revealed in the analysis of 21 articles. We focused on the effectiveness of machine learning and deep learning models, as well as on the types of characteristics. We also divided the types of predicted age variables and possible variants of EEG paradigms.

3.1. Types of Characteristics for Predicting Brain Age

This section presents a categorization of features utilized in EEG-based brain age prediction research, divided into eight functional areas. Each subsection delineates the definition and computational attributes.

3.1.1. Spectral Features

We have noted that spectral characteristics are used more often than other characteristics to predict brain age, because they show significant results. This characteristic is extracted from the power spectral density (PSD) and is most often calculated using Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), autoregressive modeling, or the Welch’s method.

The spectral characteristic indicates the signal power in all frequency ranges: delta, theta, alpha, beta, and gamma. These frequencies are associated with various mental and functional states [

23,

24,

25]. Frequently employed spectral measures encompass absolute and relative band power, which quantify the total or normalized energy within a specified frequency range. Another commonly documented metric is peak frequency, exemplified by the individual alpha peak, which may fluctuate with age or cognitive condition [

26]. Moreover, the spectral slope or flattening frequently linked to 1/f-like dynamics has been employed to delineate broadband variations in power. Numerous studies have utilized band power ratios (e.g., theta-to-alpha or alpha-to-beta) as succinct markers of brain activity equilibrium across spectral domains.

Over the course of analyzing the studies, it was found that spectral features have a very high predictive value and were used in most of the works. The most important parameters for estimating the brain age are spectral entropy, the slope of PSD [

2,

14,

20], alpha power [

14], the flatness of the spectrum in the beta range and delta rhythm power [

17], and spectral power contrasts between alpha and beta rhythms [

8].

It is worth noting that the reliability of these parameters also depends on a number of conditions, such as the duration of the EEG segment, the processing of the parameter, and, of course, the individual characteristics of brain rhythms in people of different ages. But to summarize, we can say that these studies proved that spectral features, in addition to clear biological interpretation, work well on various machine learning models, ranging from simple machine learning models to complex neural networks.

3.1.2. Temporal Features

Temporal features describe the structure of EEG signals in the time domain without transforming them into the frequency domain. These features typically capture signal dynamics over short segments and are often sensitive to developmental or pathological changes in EEG morphology. Common temporal descriptors include Hjorth parameters, namely, activity, mobility, and complexity, as well as peak-to-peak amplitude, variance or standard deviation of signal amplitude, and the zero-crossing rate.

Temporal features were applied in a subset of studies, often in combination with spectral or statistical features. In [

12], Hjorth characteristics were integrated among time-domain features for age prediction in pediatric EEG. A multimodal feature method [

17] comprised both variance and amplitude features. In [

15], statistical descriptors were extracted for machine learning models.

Sometimes temporal aspects take a secondary role compared to spectral aspects. But they also carry important information that is particularly valuable on short EEG segments or on EEG devices with a small number of channels and electrodes. It is also worth noting that there may be difficulties in their interpretability due to their high sensitivity to noise and the limitations of EEG segment length. But these parameters are crucial in the early stages of development in newborns and toddlers, where frequency characteristics are not as pronounced or reliable for predicting brain age.

3.1.3. Phase-Based Features

Phase-based features reflect temporal alignment or the synchronization of oscillatory activity both between EEG channels and within a specific frequency band. These features are widely applied to quantify neural synchrony, phase consistency, and phase–amplitude coupling (PAC). Representative examples include the phase-locking value (PLV), inter-site phase clustering (ISPC), the phase-lag index (PLI), and PAC itself, all of which aim to characterize different aspects of phase relationships in the electrical activity of the brain.

Phase-related features have been reported in relatively few studies, primarily within the context of connectivity analysis or functional integration frameworks. Dynamic functional connectivity metrics derived from phase synchronization graphs and chronnectomic analysis were introduced in [

4]. In contrast, coherence and the brain symmetry index (BSI) were only partially incorporated as phase-based measures in [

17], contributing less than spectral features.

Phase descriptors provide broad insights into the synchronization of remote brain systems as well as age-related changes. Limitations include high sensitivity to preprocessing, including EEG montage, filtering parameters, short segment lengths, and EEG units with low electrode density or few channels. Individually and collectively, these limitations reduce the reliability of these features for predicting brain age.

3.1.4. Statistical Descriptors

Statistical descriptors are simple numerical characteristics that describe the shape and spread of an EEG signal. They provide a general picture of the variability and complexity of the signal but are not frequency-dependent. Metrics such as Shannon entropy, asymmetry, excess distribution, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), and standard deviation are useful for describing the distribution of signal amplitude, how much information the signal carries, and how much it deviates from the statistical norm.

In practice, these descriptors are used as independent predictors. They are also used as part of multidimensional models. Markov entropy and sample entropy demonstrated their predictive ability for determining chronological age [

4]. Statistical descriptors have been used in many studies [

2,

6,

7,

10,

12,

14,

15,

17]. The most common features were mean, SD, skewness, kurtosis, and Hjorth parameters. Most of the time, they are used in feature clusters.

3.1.5. Functional Connectivity

Functional connectivity features show the interaction between different areas of the brain. These features are calculated by assessing the statistical dependence between EEG signals recorded from different channels. These indicators are sensitive to age in terms of network reorganization. They show how brain systems work as a whole. Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients, signal coherence, graph theory metrics, and connectivity matrices are used to calculate functional connectivity. All of these tools provide a picture of functional connectivity and the topology of these connections across the entire surface of the brain.

Special analyses of functional connectivity were most often conducted in studies employing a large number of EEG electrodes. In [

4], a Chronnectomic Brain Age Index (CBAI) was proposed based on the dynamic connectivity derived from phase synchronization, providing insights into brain maturation as a temporal representation. The authors of [

4] utilized high-accuracy graph-based models to extract dependencies between EEG channels during sleep, which allowed them to improve the accuracy of brain age prediction. They also investigated correlations across channels in windows corresponding to major stages of neurodevelopment.

It should be noted that, in earlier studies, coherence-based metrics for testing cognitive load and sustained attention also demonstrated their applicability for indexing cognitive state and functional integrity [

24].

In general, functional connectivity provides a bird’s-eye view of the global organization of brain departments, their development, and interaction. It is worth noting here that effectiveness depends on EEG montage, electrode coverage density, signal quality, and preprocessing, as well as how models can integrate these parameters. Another disadvantage is that it requires powerful computing resources due to the large number of channels.

3.1.6. Sleep-Specific Features

To capture age-related changes in sleep architecture and stage-dependent EEG fluctuations, sleep-specific features are extracted from such data. The purpose of these features is to determine the biological or functional age of the brain based on sleep markers. Most often, the power spectrum is analyzed by stage, for example, spindle power in N2, hypnodensity, and the probability of transitions between sleep stages. The proportion of time in slow-wave sleep (SWS), rapid eye movement sleep (REM), and non-rapid eye movement sleep (NREM) and the spectral entropy in key sleep intervals are also measured. Although sleep EEG is not used as often, these features perform very well.

Overall, age studies in the sleep EEG paradigm show the highest predictive results. The for the brain age index (BAI) was computed by analyzing spectral dynamics across sleep stages, revealing strong correlations with insomnia severity and OSA [

19]. In [

20], stage-specific two-dimensional EEG representations of sleep were fed into a multi-stream sequential learning model and achieved better age prediction accuracy. Specifically, sleep architecture markers such as N2 and N3 stage durations and REM sleep characteristics contributed to the high prediction accuracy (R

2 = 0.97, MAE = 4.19 years) observed in adult cohorts. It is worth noting that, in some studies, such as [

22], in addition to sleep, the state of meditation was also examined, but it was interpreted as an independent modality, and the pipeline with feature extraction was separate for it.

From a clinical point of view, sleep-specific features help to identify normal maturation and age-related decline in function. However, their application requires strictly calibrated stage markings and overnight EEG recordings with accurate scoring. It should also be noted that such features work well in sleep EEG but perform poorly in non-sleep paradigms. Therefore, they are not universal in predicting brain age.

3.1.7. Learned Representations

Learned representations are features directly extracted by a neural network without human intervention during the model training process. Manual feature selection is completely absent in this approach. Most often, these representations are extracted from raw EEG or minimally cleaned data. These features are immediately adjusted to the goal of determining brain age. Such features include the activation of intermediate layers and recurrent embeddings generated by CNN encoders, as well as latent vectors, autoencoders, and self-learning systems. The purpose of these features is to capture the hierarchical and distributed patterns of EEG, which are quite difficult to describe manually.

It is worth noting that, in recent years, with the development of multi-stream models, this approach has become more commonly used in studies to determine brain age. A multi-stream sequential model is used to clarify hidden spatiotemporal dynamics in [

20]. In [

21], a long short-term memory (LSTM) network was used, and the resulting neural embeddings were then employed as predictors. In [

21], feature maps generated using Wasserstein generative adversarial networks with gradient penalty (WGAN-GP) were merged for subsequent training. In [

14], SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAPs) were applied to compare the contribution of trainable and handcrafted features across different model configurations.

Learned features allow for the detection of intricate, multiscale signal patterns that might not be reachable using conventional feature engineering and support end-to-end modeling pipelines. Still, these representations are quite sensitive to data volume, model architecture, and regularization techniques and sometimes lack understanding. Additionally, standardization in EEG-based brain age prediction research is restricted by the variety of learning frameworks and training methods, which limits the comparability of learned features across studies.

3.1.8. Feature–Outcome Associations Across Age Variable Types

In order to understand which types of features were most predictive of brain age, we conducted a cross-sectional analysis for different types of age variables. CA, BAI, CBAI, FBA, and brain age were considered. Each of these brain age variables influences which characteristics will be more significant and also reflects unique neurobiological and statistical features. For predicting CA, spectral features performed best. Among them, the most important were the PSD slope and alpha band power [

13,

14,

17]. A logical connection with alpha power was also demonstrated in [

8], where differences in alpha–beta amplitude were noted. In addition to spectral features, statistical descriptors such as spectral entropy and signal variance also made a significant contribution [

17]. Deep learning models predictably achieved high accuracy in determining CA, especially on large datasets, using trained representations [

20,

22].

If the goal is not the age itself but rather the deviation from brain age, such as BrainAGE or BAI, then the role of temporal and statistical features increases. This is particularly noticeable in sleep-oriented models, because these features capture individual variations that go beyond simple linear aging. BAI has been found to be more related to stage-specific sleep features and entropy metrics than to standard power measurements in frequency ranges or any bands [

14,

15,

17,

19]. Goals such as BrainAGE require careful bias correction and are highly sensitive to preprocessing, which is the reason for low interpretability and transferability to other datasets. In studies of infants and the FBA variable type, it was found that spectral and temporal features on short segments provide the highest accuracy [

10,

16]. PMA correction as well as the age of sampling directly affected the effectiveness of these features.

In summary, it can be noted that spectral features have the greatest predictive power for determining CA and FBA. Learned representations dominate in most deep learning models, while entropy and statistical descriptors play a major role in BAI research. There are few direct comparisons of feature rankings between different age variables, which highlights the need for further research and the systematic benchmarking of feature types for predicting brain age from EEG datasets.

3.2. Machine Learning Approaches

A systematic overview of EEG-based brain age prediction machine learning models is provided. The study includes chronological age, functional brain age, and classification-based models organized by goal variables. The results in

Table 3 help to choose models and feature attributes.

The age range of the study cohort influences the interpretation of prediction accuracy measures. MAE at one month is considered a typical measure for studies involving infants (aged 0–12 months), as it covers approximately 8% of the total range. MAE after 5–7 years shows a comparable relative error (about 8–10%) and is usually considered a suitable indicator for studies involving adults of a wide age range (e.g., 18–80 years). High predictive accuracy is confirmed by R

2 values above 0.7 regardless of age group. The results presented in

Table 3 should be interpreted in accordance with these recommendations.

3.2.1. Models for Chronological Age Prediction

CA is often the target variable for predicting brain age. Classic machine learning models, SVR, RF, and Elastic Net, with manual data selection have shown either moderate or high results [

7,

17]. Although many of these models have not been externally validated, tree-based ensemble methods, including XGBoost, have achieved particularly low MAEs in pediatric or restricted-range cohorts [

14], while stepwise regression and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) showed the best results [

6].

Deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) have shown better generalizability on more heterogeneous adult datasets. For instance, using a four-layer CNN trained on short temporal EEG segments, an MAE of 5.96 years and an R

2 of 0.81 were reported in [

9] (

Table 3).

In [

20], an MAE of 4.19 years and an R

2 of 0.97 were achieved using a Swin Transformer (

Table 3). Similarly, [

19] reported a high correlation between the BAI and clinical indicators of the insomnia severity index. Even though these studies were conducted on well-annotated datasets and are still sensitive to bias correction and variability in processing, they highlight the high clinical potential of BAI as a biomarker.

3.2.2. Models for Functional Brain Age

FBA in newborn investigations is a surrogate for brain function, therefore suggesting neurodevelopmental maturity instead of chronological age. Resting-state EEG recordings tend to forecast PMA in these systems. In [

15], an MAE of about one month was reported using the XceptionTime model. In [

10], comparable findings were obtained using the SVR model. These techniques rely on short EEG segments and require strict artifact rejection to ensure data quality. Often, FBA forecasts are tested to establish their clinical significance against acknowledged neurodevelopmental criteria.

3.2.3. Classification-Based Methodologies

Some studies use age group classification rather than regression. This is particularly true for studies with small sample sizes or data divided by age. For example, individuals were classified into six predefined age groups with 93.7% accuracy using a deep bidirectional long short-term memory (BLSTM) architecture [

11]. The classification accuracy of support vector machines (SVMs) applied to paralinguistic EEG characteristics was reported as 99.6% in [

3].

The disadvantages of classical models include, in most cases, the lack of validation on external samples and lack of detail and interpretability, which limits their generalizability to larger datasets.

3.2.4. Summary by EEG Paradigm and Age Group

The performance of models in EEG-based brain age prediction differs greatly between EEG paradigms (

Table 1). In resting-state EEG studies, spatially informed deep learning models have produced the best outcomes. Although deep learning design did not always take the lead, it did produce the best results on large datasets [

2]. In study [

9], a four-layer CNN achieved an MAE of 5.96 years, outperforming traditional machine learning models within that dataset; however, direct cross-study algorithm comparisons are limited by dataset heterogeneity. The XGBoost achieved low MAE (1.62 years) on a narrow age range sample using stratified cross-validation; however, the absence of external validation limits the generalizability of these findings [

14].

It is safe to say that currently, deep learning models, including CNN, demonstrate the highest results in assessing brain age based on sleep EEG. One example is the work in [

20], which used a Swin Transformer and achieved an MAE of 4.19 years. In [

19], correlations were found between the model’s predictions and clinical indicators of sleep efficiency.

It is still quite difficult to draw firm conclusions from ERP-based studies, as they have not been studied extensively in the context of brain age prediction. The only notable study is [

18], which achieved an area under the curve (AUC) metric of 0.91. It should be noted that the best results were achieved using SVR models and kernel-based techniques. However, the interpretability of the data is limited by the fact that it was used for age groups rather than for specific ages.

In talking about studies with the target variable BAI, they have shown high clinical utility. Using the DenseNet model, an MAE score of 5.4 and a correlation r of 0.80 were obtained based on the results in [

19]. In addition, BAI was associated with the severity of sleep disturbances, indicating its potential as a biomarker of sleep-related brain health.

PMA served as the definitive reference for FBA in studies involving neonates. The SVR model achieved an MAE of 1.3 months [

10]. XceptionTime gave an MAE of one month and R

2 = 0.67 [

15]. This indicates that FBA can be estimated fairly accurately from short EEG segments.

3.2.5. Statistical Precision

In this section, we looked at how rigorous these studies were from a statistical point of view and focused on three aspects. First, we examined whether the authors verified statistical assumptions, such as the normality of distribution. Second, we evaluated whether they accounted for the large number of tests producing random results. And third, we considered whether effect size indicators were for assessing practical significance.

Although several studies [

8,

16] explicitly state that they verified the correctness of the statistics, most studies [

4,

9,

18,

20] have no such information, and even in some methodologically reliable works [

2,

13] where the verification data is not specified, it is possible that the authors performed it but did not display it, but we cannot be sure and assess the reliability of the conclusions.

We note that multiple comparisons tests were not mentioned in most studies. While many studies employed dimensionality reduction or embedded feature selection (e.g., SHAP values, recursive feature elimination), explicit mention of formal corrections, such as the Bonferroni adjustment or false discovery rate (FDR) control, was rare. In [

18], authors compared ERP indicators between age groups but did not specify whether multiple testing correction was applied. In [

8], researchers used a more rigorous approach, applying permutation-based inference and recursive variable selection for more accurate feature selection. In other studies, refs. [

14,

15,

21], it remains unclear whether multiple testing was statistically controlled, as such procedures may have been performed but not explicitly reported.

There were certain difficulties in systematizing and unambiguously calculating effectiveness in studies due to the fact that different effectiveness indicators were used to compare models. For example, for the most part, these indicators were the MAE, root mean square error (RMSE), and R

2, while some studies presented statistical effect size metrics like Cohen’s d and η

2 in [

4,

16]. In other studies [

5,

9,

12], there were no estimates of the effect size. It is potentially more difficult to apply this in clinical settings and interpret the results broadly. Several papers used explainability tools (e.g., SHAP values, partial dependence plots), which enhance qualitative understanding; however, quantitative indicators of effect magnitude were generally lacking or not explicitly reported.

Although most studies demonstrated relatively high validation and modeling metrics, documentation of conclusions was often incomplete. Among the studies analyzed, only two studies [

8,

16] explicitly tested all elements of statistical rigor. All of this collectively limits clinical applicability, generalizability, and reproducibility for future studies.

3.2.6. Feature–Model Interactions

We conclude that the alignment between features and machine learning approaches is a significant factor in prediction success. For example, classical algorithms such as support vector regression (SVR), random forest (RF), and extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) work particularly well with statistical, spectral, and temporal features. Tree-based models such as XGBoost and RF consistently rank the PSD slope and alpha power as leaders, and SHAP analysis confirms their importance from run to run. Adding amplitude contrasts and spectral statistics to partial least squares regression (PLS) and multiblock PLS (M-PLS) makes them more effective. To simplify models and improve interpretability, feature selection methods (e.g., SelectKBest) and explainability tools (e.g., SHAP) are often used. In cases where models are trained on raw EEG data, neural networks such as LSTMs and transformers show the best results. They often out-perform CNN in such tasks.

These models can internally learn hierarchical or distributed representations without the need for manual feature engineering, eliminating that requirement. In [

20], a multi-flow sequence model was used to forecast brain age without the use of manually picked features, attaining significant prediction accuracy. LSTM-based architectures could effectively make generalizations from just four EEG channels acquired using low-cost wearable devices [

21]. The combined use of learned representations and manual features improved the predictive performance [

2]. In conclusion, deep neural networks are typically more efficient for learned representations. Traditional machine learning models work effectively with the usual spectral and statistical features.

Studies that incorporated mixed feature sets, such as [

14,

20], achieved a favorable balance between predictive performance and model interpretability. However, only a few investigations to date have conducted direct comparisons of different model architectures using identical input features, which limits the generalizability of existing findings.

Model performance in EEG-based brain age prediction is strongly influenced by the compatibility between input feature type and computational architecture. Spectral features continue to dominate classical machine learning approaches, whereas deep learning pipelines derive their strength from internal representation learning. Future comparative analysis initiatives should focus on standardizing function–model pairs to formulate best practices.

4. Discussion

This chapter summarizes the conclusions of the review on brain age determination based on EEG datasets. We note the statistical limitations and analyze methodological issues. Attention is paid to four main aspects: the definition of target indicators, preprocessing options, methodological rigor, and future directions for development.

4.1. Methodological Critique

The methodological rigor of brain age prediction was systematically evaluated. The main aspects are the configuration of the validation strategy, the risk of overfitting, code availability, and the possibility of data replication.

In most scientific studies, k-fold cross-validation was used or is most common. This is usually 5-fold or 10-fold validation. A smaller number of studies have used cross-validation. As for external validation on independent datasets, it has only been used in isolated cases [

4,

10,

15,

16,

20].

Assessment of overfitting risk revealed a wide spectrum of practices (

Table 4). Studies based on smaller samples that also lack external validation (e.g., [

11,

18]) demonstrated a higher susceptibility to overfitting. In contrast, large-scale studies employing cross-subject designs and nested validation incorporated more robust safeguards [

2,

9,

22]. Intermediate risk was noted in studies that used internal validation without stratification or tuning constraints.

Open science practices and reproducibility varied considerably. While some studies provided public access to datasets and source codes (e.g., [

2,

4]), others, particularly those involving proprietary clinical data, did not make the codes or data openly available.

Thus, it is important to be able to reproduce experimental results, and the need to develop standards for tests is becoming increasingly relevant.

Table 4 presents a comparative assessment of methodological rigor, including the risk of overfitting, validation schemes used, availability of external replication, and availability of data and codes. The table includes direct links to publicly accessible source repositories.

4.2. Preprocessing Strategies

With regard to reprocessing strategies for determining brain age, it should be noted that they are quite diverse. This applies to the data segmentation format, the characteristics of the equipment, and the processing of the EEG data itself. This is all a consequence of the lack of standards for data preprocessing, as well as the influence of the EEG itself as a flexible method of collecting information.

The EEG equipment used in the analyzed studies can also be divided into three configurations. The first is a low-density device with up to four electrodes. It is typically used in mobile EEG applications, such as the Muse S system [

22]. The low-density configuration was also used in [

7]. The second configuration is medium-density systems with 14 to 36 electrodes. These include Emotiv headsets. Medium-density systems were used in [

6,

11,

17]. The third type is devices with an electrode density ranging from 64 to 128. These devices were used in [

2,

15,

20]. A distinctive feature of such datasets was their large scale or clinical conditions.

The filtering protocols also varied considerably. It should be noted that bandpass filtering was practically a universal step in data filtering, but the cutoff frequency differed from study to study. In [

8], filters were applied in the range from 0.1 to 45 Hz, and in [

20], were applied in the range of 0.3–35 Hz. Dual-notch suppression was used in [

9], while in [

17], notch filtering was implemented.

Data is often downsampled to facilitate calculations so that the sampling rate is approximately 128 to 500 Hz. A frequency of 256 Hz is most commonly used in EEG studies, but it should be noted that some of the reviewed studies used either lower frequencies, such as 128 Hz in [

22], or higher frequencies, such as 250 Hz in [

8].

Artifact rejection was recognized as essential for preserving signal quality. Independent component analysis (ICA) was widely used to remove ocular and muscular artifacts in [

15,

18]. Other studies incorporated artifact subspace reconstruction (ASR), as seen in [

10]. Some adopted hybrid pipelines combined manual inspection, statistical heuristics, and automated algorithms. The autoreject framework was employed in [

2], while a multistep rejection protocol based on eye movement, signal amplitude jumps, and kurtosis thresholds was applied in [

9]. As one of the preprocessing elements to remove excess noise and leave only useful data, singular spectrum analysis (SSA) was applied in [

12].

Segmentation strategies varied according to study design and modeling approach. Short segments of 1–2 s were used in neonatal or real-time settings. For instance, in [

15], 2 s segments were used for classical models and 5 s segments for deep learning. In [

17], 60 s windows with 50% overlap were applied. The studies [

9,

22] used medium segments ranging from 5 to 10 s in length. For long segments lasting more than five seconds, [

19] converted minutes from a time measurement to frequency measurement. And they checked the predominance of brain rhythms that are most represented in the signal.

Eye-condition handling represented another point of divergence. Some studies explicitly modeled both eyes-open and eyes-closed states. For instance, in [

9], models were trained on both conditions. Study [

2] adhered to Brain Imaging Data Structure (BIDS) conventions in distinguishing states, whereas other studies either omitted this detail [

6,

7] or included mixed-state recordings, particularly in pediatric datasets [

16].

The most effective models included filtering within a frequency range of around 0.1 to 45 Hz over segments lasting from 5 to 30 s. It is surprising that even mobile EEG systems with a small number of electrodes show competitive results. Therefore, they can also be used to predict brain age. In most cases, ICA and ASR are used to clean up artifacts. It can also be concluded that eye movement significantly contaminates the signal, and when the signal is cleaned up from this artifact, it provides a noticeable performance gain.

Beyond these technical issues, epoch extraction and artifact removal approaches differed widely and were inconsistently stated. In this review, we documented the preprocessing approaches where available. However, the lack of standardized protocols made it difficult to systematically compare their impact on brain age estimation. Epochs ranged from short one-second moments to complex overnight recordings, and artifact removal methods ranged from manual review to automatic algorithms with different parameters [

2]. All this diversity reflects the evolving nature of the field, but it limits direct comparison and makes it very difficult to assess the impact on model performance.

4.3. Target Variable Definition and Interpretation

The most significant complicating factor for the analysis of brain age prediction is the methodological difference in how the target variable is defined. The literature presents at least five distinct formulations of age-related outcomes, each with specific conceptual assumptions, statistical characteristics, and clinical implications.

The main prevalent target variable is CA, representing the participant’s actual age in years, or weeks in neonatal cohorts, at the time of EEG recording. In the majority of studies, CA is used as a dependent variable. The nuance of CA is that it does not take into account details such as individual differences in brain maturation. Although this is standard practice for most studies, this variable does not allow for significant differences in neurodevelopment to be reflected [

2,

8,

9,

17,

21,

22].

Predicted BA is interpreted not simply as chronological age but as an assessment of brain maturity. Research in [

8] shows that BA can only be considered an independent indicator when its importance is confirmed either by testing over time or by linking it to clinical outcomes.

To solve this problem, some studies have introduced the BrainAGE indicator, which is the difference between the predicted BA and the actual CA. It shows the deviation from normal aging: the brain is maturing faster than normal. If the results are negative, the brain is developing more slowly than normal. But BrainAGE has a weakness. It can be distorted by statistical effects, such as systematic bias in regression. Special methods like linear residualization are proposed to correct such distortions, but in practice, not all studies use them yet [

17,

19,

20].

BAI is a variable that accounts for systematic error in determining brain age and is tested against functional outcomes. The conceptual difference with brain age is that, here, it accounts for bias and model error. It is also checked to see if it is indeed related to functional or clinical outcomes. BAI is a purified and validated version of brain age assessment. It is most often used in sleep studies. BAI may reflect an association with cognitive function, as investigated in [

20]. Study [

19] investigated the relationship between insomnia and BAI.

In most cases, models are trained in how to predict CA or calculate BA. However, in the context of newborns, this does not make sense, because calendar age is not that important, and functional maturation is much more significant. That is why PMA, the age of the child from the moment of conception, is used instead of CA. FBA is used to predict PMA instead of CA, as in [

10,

15]. It checks whether development is normal for the current period. The main goal is not to determine age but to check for developmental delays.

Frequently, studies predict normal calendar or chronological age. However, authors interpret this and use it differently. As for the BrainAGE indicator, it is also applied inconsistently. Some studies adjust for bias while others do not, which may produce results that are more significant than they actually are. FBA is a completely different approach and is more difficult to compare with other metrics. In addition, some studies predict age not by number but by certain group categories, as is done in [

3,

11]. This also adds complexity to comparing results and attempting to draw general conclusions.

To fairly compare models that determine brain age based on EEG data, it is necessary to clearly indicate which age variable is being predicted, how it is calculated, how it is adjusted, and how it is interpreted by the authors.

The interpretation of age-related outcomes is further complicated by the inconsistent reporting of biological and clinical factors that may influence brain age estimates. Although sex differences affect EEG spectral parameters, with statistically significant differences in theta and alpha band power between males and females [

11,

12], only a few studies performed sex-specific analyses. While we documented sex distribution where available (

Table S1), the heterogeneity in analytical approaches prevented the systematic comparison of sex effects on brain age prediction.

With few studies reporting medication usage or controlling for it as a covariate, the literature reviewed failed to show its effects on EEG parameters and brain age assessment. Sleep quality indicators, such as total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and awakening after sleep onset, were inconsistent across sleep studies [

19,

20]. Some studies demonstrated significant associations between sleep quality indices and brain age acceleration [

19], highlighting the importance of systematically documenting these parameters. Cognitive and arousal states during resting-state recordings were rarely monitored or standardized [

2,

9,

17] despite their potential impact on EEG signal features and age estimates.

4.4. Integrative Discussion

In this chapter, we identify methodological trends in the field of brain age prediction, summarizing the results by target variable formulation type, EEG paradigm, machine learning architecture, and feature type.

4.4.1. Best-Performing Models

Model performance differed systematically based on both the type of age-related target and the EEG acquisition paradigm. In predicting CA, the highest performance on broad adult datasets was achieved by a four-layer DCNN, which reported an MAE of 5.96 years and an R

2 of 0.81 [

9]. For instance, in [

14], the MAE was only 1.62 years in a sample of 5 to 22 year olds using the XGBoost model. However, there was no external validation, and thus, we cannot be sure that, on other datasets, this approach will show itself to be as highly accurate.

In the context of the BAI variable and EEG during sleep, the most accurate results were obtained. Two elements are significant in this context. First, it is the EEG paradigm. During sleep, brain rhythms are clearly expressed, making it easier to determine brain age and the stage of development. The second factor is the modern architecture of the Swin Transformer model that is well-suited for time series and can calculate subtle patterns. This contributed to the achievement of such a high MAE of 4.19 years and R

2 0.97 in [

20]. The R

2 value is extremely high for sleep EEG studies, where typical values range from 0.70 to 0.85, and it appears to indicate a complex temporal structure of nighttime sleep recordings, as well as the ability of the Swin Transformer to capture long-term relationships. Another study, [

19], implemented DenseNet, resulting in an MAE of 5.4 years and a correlation coefficient of r = 0.80. In both instances, the BAI exhibited a significant correlation with clinical indices, primarily regarding insomnia severity and reduced durations of N3 and REM sleep.

In neonatal populations for FBA, with PMA as the reference, XceptionTime yielded the most favorable findings. Study [

15] obtained excellent results, with an MAE of one month and an R

2 of 0.82. Study [

10] also achieved highly accurate results, slightly less than those in [

15]. They used SVR as a model and entropy and brain activity as variables in the delta range. The MAE was only 1.3 months, which is quite a remarkable result.

Performance also differed according to the EEG paradigm. In resting-state EEG, the most accurate results were shown by models when not only checking signals in the time and frequency range but also when taking electrode localization into account. Adding deep learning to this, the accuracy of the predictions increased. In [

2], using a four-layer CNN with learned spatial–spectral representations, performance achieved an R

2 of 0.69 with a mean absolute error of 7.75 years. DCNNs surpassed traditional regression methods when temporal and spectral information were integrated [

9].

CNN and transformer models performed better on sleep EEG. This tendency was mirrored by the Swin Transformer used in [

20] and the DenseNet model used in [

19], which achieved high R

2 values and strong associations with clinical variables. These models frequently used spectrogram-based representations and large amounts of nightly EEG data.

Age groupings were more frequently predicted than the continuous age in investigations on ERP datasets. Using ERP-derived characteristics and an SVM classifier, study [

18] classified age groups with an AUC of 0.91. Because ERP is made up of relatively brief time intervals that change from trial to trial, it is rarely used to forecast brain age as a continuous number.

4.4.2. Most Informative Features

The significance of features was mainly affected by two factors. First, what the target variable was, and the second factor, which was the EEG paradigm that was used in the study. Chronological age prediction, spectral features such as alpha power, PSD slope, and spectral entropy were frequently identified as important contributors to model performance [

6,

9,

14]. In terms of time intervals, features such as signal energy and Hjorth complexity were most often useful for short segments.

For the target variable BAI, the most accurate predictions were obtained in sleep EEG datasets using time–frequency representations. In [

20], BAI estimates were associated with sleep architecture, particularly the durations of the N2 and REM stages, while in [

19], DenseNet-based BAI predictions correlated with clinical indices such as insomnia severity and sleep efficiency.

Nonlinear and entropy variables were among the most informative user predictors for FBA. The delta-to-alpha power ratio, complexity index (CI), and multiscale entropy were identified as key features in [

15]. The importance of entropy and fractal dimension characteristics was confirmed in [

10], with a mean absolute error of only 1.3 months.

The EEG paradigm profoundly impacts the selection of characteristics. Resting-state EEG studies primarily used spectral power, entropy-based descriptors, and statistical moments such as kurtosis and skewness. These were particularly salient in conventional machine learning pipelines. On the other hand, EEG studies performed during sleep have discovered characteristics related to sleep architecture, such as power dynamics at certain stages and signs of hypnodensity. In specific studies, deep learning models often show better results compared to traditional models. However, claims about the superiority of architecture are limited by the complexity of dataset heterogeneity, which makes it difficult to directly compare models across different studies.

ERP-based studies typically focused on event-locked features such as peak amplitude and component latency [

3,

18]. In studies involving auditory or vocal stimuli, additional spectral features such as Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) were also used.

4.4.3. General Limitations and Future Directions

The main problem with studies predicting brain age using EEG is the lack of external validation. Validation was performed using only individual datasets in [

4,

10,

15,

16,

20] (

Table 4). Recent methodological recommendations emphasize the importance of external validation and standardized reporting when determining brain age using neuroimaging [

27]. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of studies using reliable models that allow for more accurate assessment indicators. Most studies were limited to narrow cohorts, often with a limited age range, which increased the risk of overestimation and limited their applicability to different population groups. There is a need for uniform methodologies for comparative analysis and multicenter datasets that comply with recognized standards for EEG data collection.

The lack of standardized risk assessment tools, like PROBAST or QUADAS-2, is a methodological limitation of this review. Due to the diversity of prediction targets (CA, FBA, BAI, and BrainAGE), study designs, and validation methods, it was difficult to implement a uniform quality assessment system. Future systematic reviews should develop and apply quality assessment criteria that take into account the unique properties of prediction. Variability in preprocessing continues to be a significant source of methodological variation among research papers. Studies reported a wide range of bandpass filtering parameters, from 0.1–45 Hz to 1–70 Hz. In addition to filtering differences, artifact removal procedures were applied inconsistently across studies. Artifact removal procedures, such as ICA or ASR, are used inconsistently in most studies. The segment duration varied significantly, ranging from brief one-second segments to comprehensive full-night recordings. All of this makes it difficult to compare these studies. If the scientific community adopted a single preprocessing paradigm, for example, in accordance with BIDS, it would be possible to compare results more fairly and reproduce them more easily.

Channel density showed significant heterogeneity across different studies, ranging from four-channel mobile EEG devices [

22] to high-density arrays with 128 channels [

14]. This variability is a potential problem that complicates the evaluation of model performance. Direct comparisons of MAE values across studies using different channel configurations should be approached with caution (e.g., in study [

14], with 128 channels, MAE = 1.62 years, and in study [

9], with 26 channels, MAE = 5.96 years), since increasing channel density can provide more complete spatial information regardless of the model architecture [

22].

The age of the dataset, sample size, and EEG paradigm make it difficult to compare the effectiveness of algorithms across multiple studies. In study [

14], using XGBoost, the MAE was 1.62 years in a limited age range (children and adolescents, 5–22 years), but in another study, [

9], using DCNN, the MAE was 5.96 years in a larger cohort of adults (5–88 years). A direct comparison of these MAE values is statistically invalid due to differences in age distribution. It is important to note that none of the studies in this paper considered a set of algorithms using identical datasets and feature sets, making it impossible to establish the clear superiority of any approach.

The presentation of performance metrics is inconsistent, making it difficult to compare studies. Many studies (designated as “NR” in

Table 3) did not report R

2 or RMSE values but only analyzed the MAE. For successful comparison in future studies, uniform data presentation methods such as MAE, R

2, and RMSE should be used. Bias correction for age-related prediction targets, especially BrainAGE and BAI, is also inconsistently applied. Techniques such as linear residualization are essential to mitigate regression-to-the-mean effects, yet only a small minority of studies (fewer than one quarter) explicitly reported using such adjustments. Without bias adjustment, predicted brain age outcomes may be statistically misleading and clinically ambiguous.

The interpretability of models is a notable limitation to consider. It should be noted that some studies, such as [

14], used interpretation tools such as SHAP value analysis, while [

15] applied the feature ablation method. However, most studies still relied on opaque architectures in deep neural networks and transformers without attempting to identify the features that are most important for predicting age. It would be good practice to adopt the inclusion of explainability tools such as saliency maps, layer-wise relevance propagation, and feature attribution methods as the standard so that the influence of features on the predictive properties of the model can be clearly stated.

The next limitation is unbalanced datasets. In the studies we analyzed, there were more young people or adults among the subjects, for example, older people and children were not represented (

Table S1). This causes bias in the indicators. In other words, the model learns to predict well for the groups that are represented but is ineffective on data that was not included. It is worth noting that some studies use resampling or stratified sampling by age. This problem is particularly important for models that predict age, because they produce errors on unbalanced data.

In addition to the use of predictive models in research, problems may also arise in clinical application. The reason for this is that models are trained on carefully selected datasets that may not always reflect the real diversity of patients. It is also unclear how BrainAGE or BAI indicators should be used in practice. Their integration into diagnostics, application in longitudinal monitoring, and determination of appropriate thresholds for decision-making remain important issues for future research. In order to bridge this gap between clinical practice and research and to make these parameters useful for doctors, a joint effort by scientists, clinics, and regulators is required.

The main limitation of this review is the inability to thoroughly compare various critical aspects that may influence the assessment of brain age. As discussed in

Section 4.3 and

Section 4.4, gender differences in drug effects, sleep quality, cognitive state at the time of recording, and preprocessing procedures can significantly influence EEG characteristics and, in theory, distort brain age estimates. Although these factors were documented when available, inconsistencies in reporting methods prevented a meaningful systematic comparison of their effects. It makes it difficult to evaluate their model performance and clinical application contributions. To facilitate reliable comparative analysis and clinical translation, these characteristics should be reported more consistently in the future.

5. Conclusions

This review combined 21 studies on predicting brain age using EEG datasets. Various groups of participants (

Table 2 and

Table S1), different EEG paradigms (

Table 1), and modeling methods (

Table 3) were used and investigated. During the analysis, we found that the quality of model results was most influenced by how the target variable was defined, which EEG paradigm was used, and which features were extracted. For brain age indicators among infants, temporal and frequency features as well as entropy metrics proved to be particularly useful. For chronological age prediction, deep neural networks and ensemble models generally yielded the highest accuracy, while spectral and nonlinear features were frequently among the most predictive. The problem of interpretation remains open, especially in deep learning models, where algorithms work like black boxes. Moreover, the majority of research lacked external validation, failed to consistently comply with rigorous statistical requirements, and often neglected bias correction. At present, EEG-based brain age is best considered a research signal rather than a validated clinical biomarker. Future research should focus on clear validation procedures, improved reproducibility, generalized reporting, and the use of biologically meaningful predictors that will be useful for diagnosing developmental disorders and will have clinical significance.