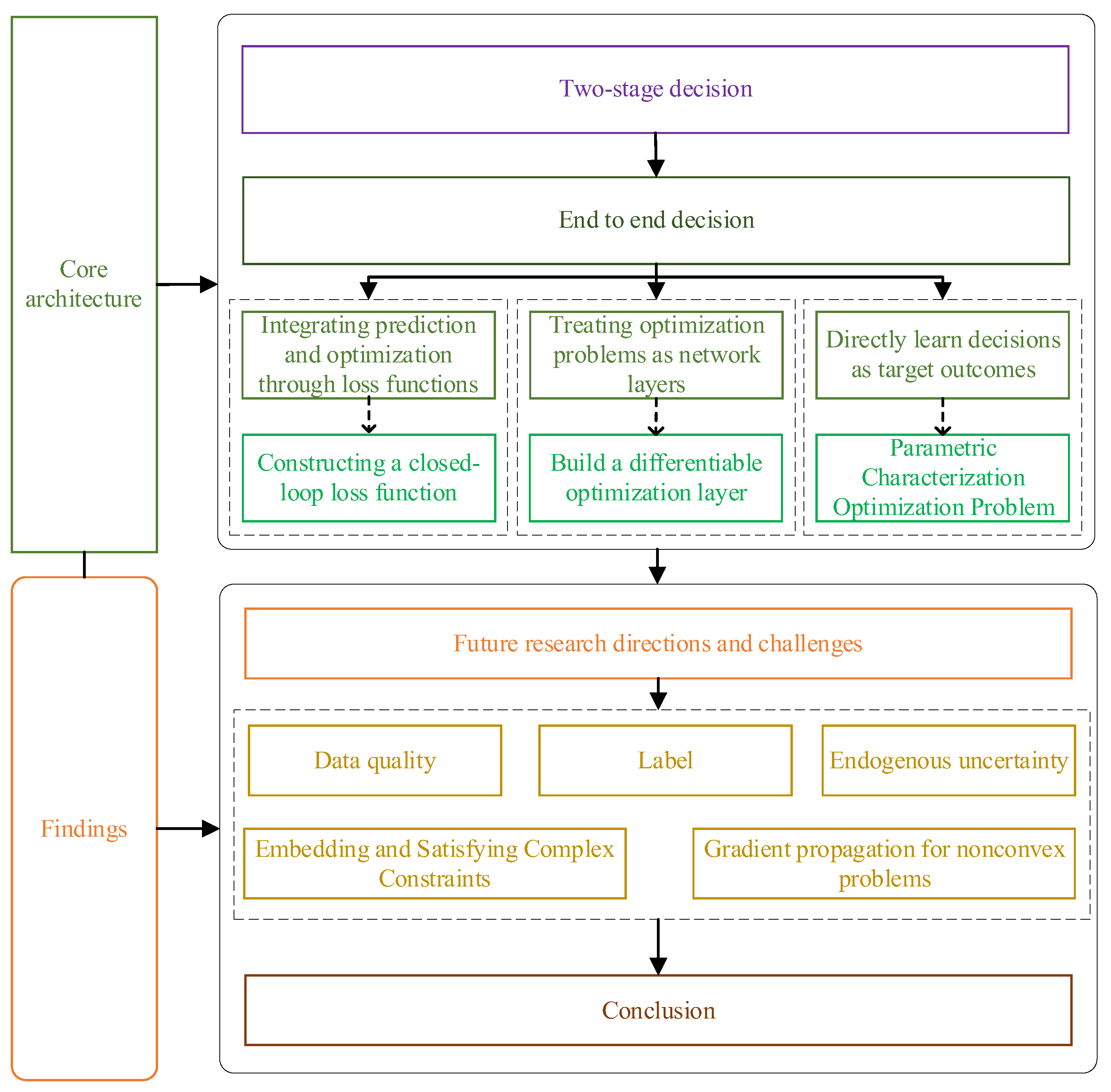

A Review of End-to-End Decision Optimization Research: An Architectural Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

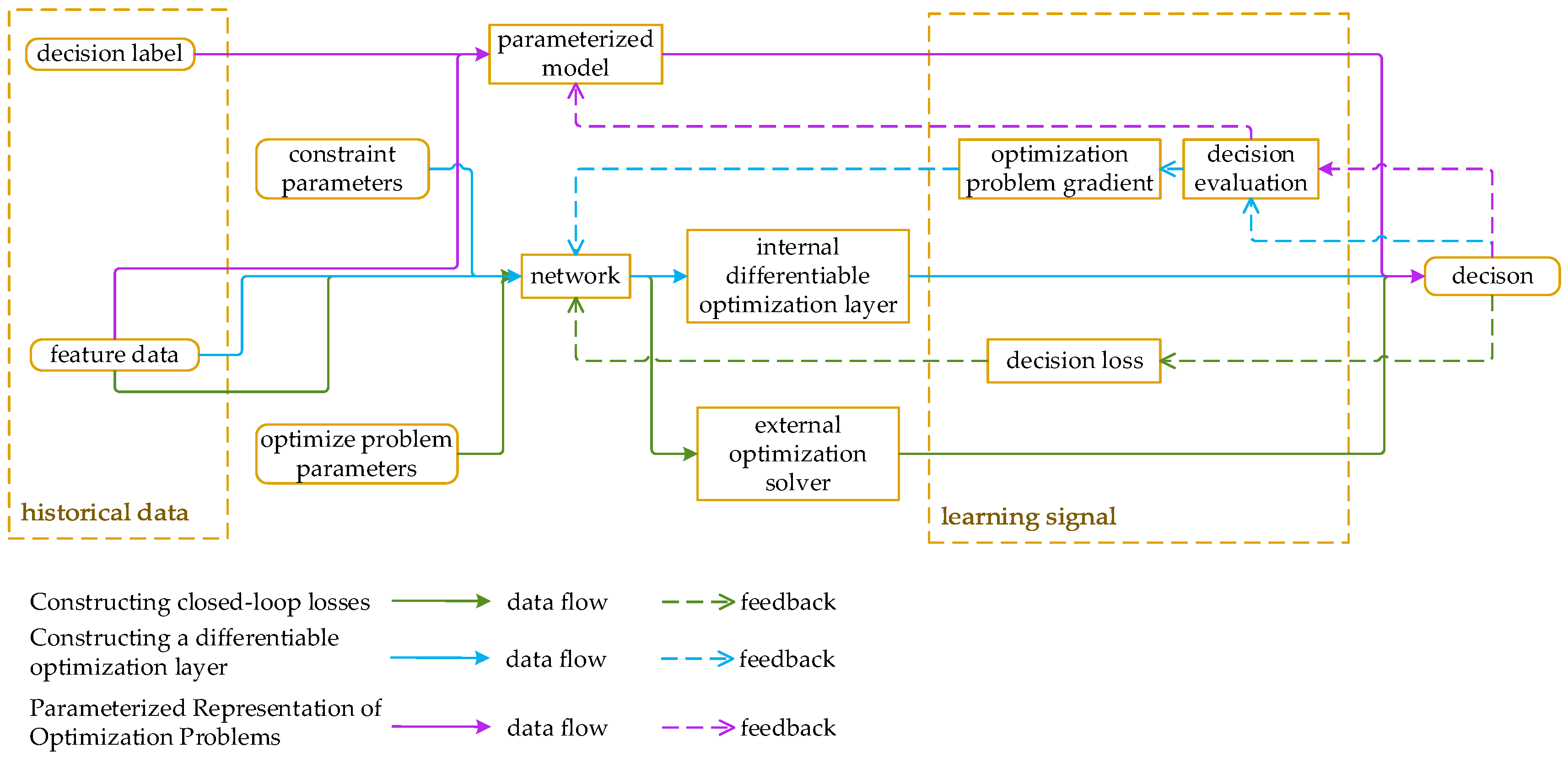

- Architectural Categorization: Based on how prediction and decision modules are integrated, this review categorizes end-to-end decision optimization into three paradigms: (a) constructing closed-loop loss functions, (b) building differentiable optimization layers, and (c) parameterized representation of optimization problems.

- Comparative Analysis and Practical Guidance: Combined with specific cases, this review analyzes and contrasts the strengths, limitations, and applicability of each paradigm, offering actionable recommendations for their deployment in real-world settings.

- Critical Synthesis of Challenges and Opportunities: This review identifies and analyzes the challenges facing end-to-end decision optimization in practical scenarios—including issues related to data, complex constraints, non-convexity, decision-dependent uncertainty—and highlights emerging opportunities for future research.

2. Literature Review Analysis and Research Framework

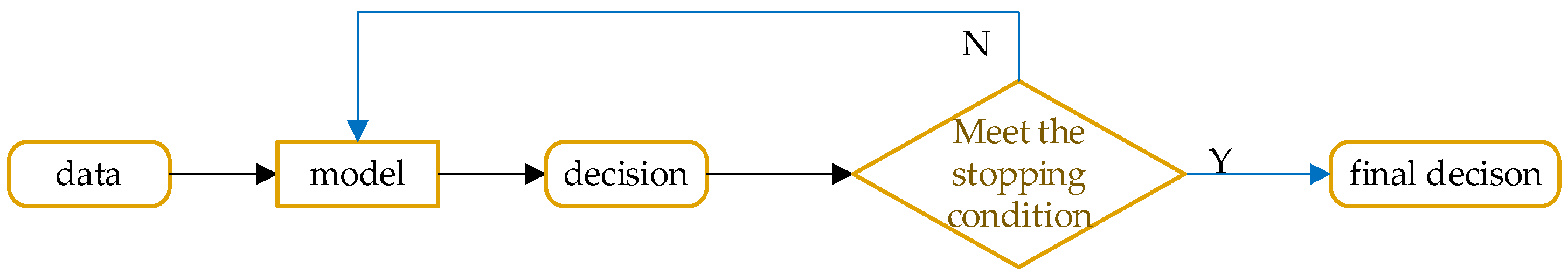

3. Decision Optimization

3.1. The Concept of Decision-Making

3.2. Decision Optimization Problems

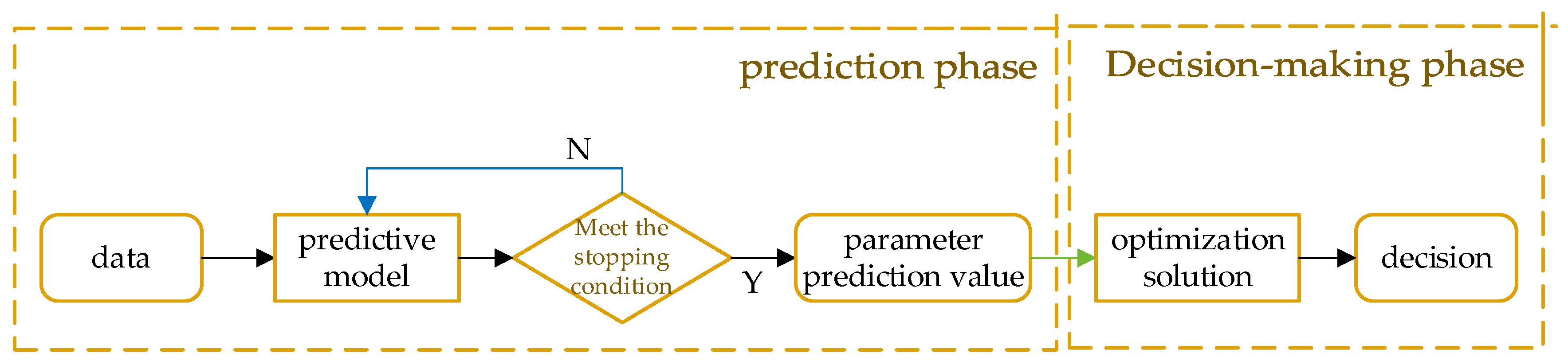

3.3. Two-Stage Decision-Making: Prediction Followed by Optimization

- Prediction stage:

- Optimization stage:

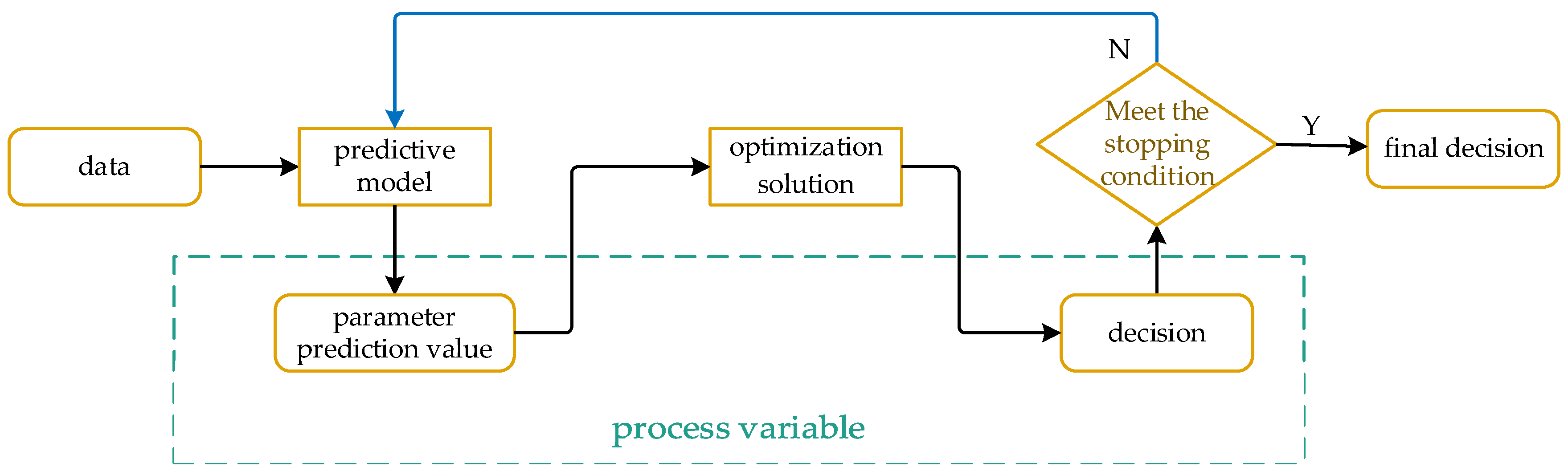

4. End-to-End Decision-Making Architecture Integrating Prediction and Optimization

4.1. Constructing Closed-Loop Losses

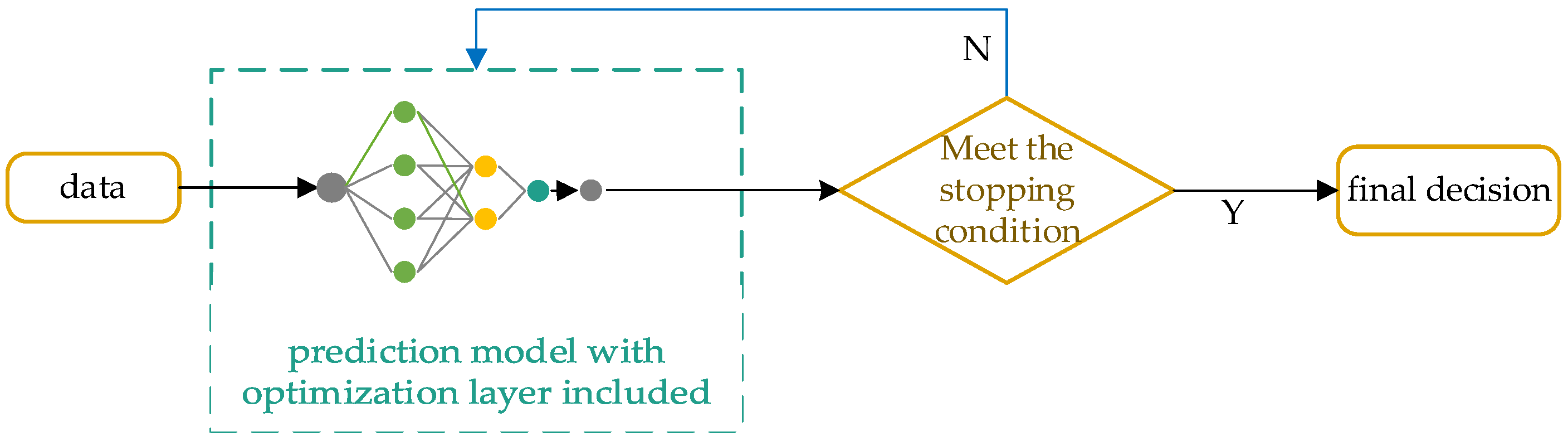

4.2. Constructing a Differentiable Optimization Layer

4.3. Parameterized Representation of Optimization Problems

4.4. Architectural Comparison and Design Implications

5. Current Research Directions and Challenges

5.1. Data Sources

5.2. Label-Related Issues

5.3. Intrinsic Uncertainty

5.4. Gradient Propagation for Non-Differentiable Decision Modules

- (1)

- (2)

- Encoding heuristic rules for combinatorial optimization as differentiable operators [57];

- (3)

5.5. Embedding and Satisfying Complex Constraints

6. Summary and Prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bertsimas, D.; Kallus, N. From Predictive to Prescriptive Analytics. Manag. Sci. 2020, 66, 1025–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmachtoub, A.N.; Grigas, P. Smart “Predict, then Optimize”. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y. Using a Financial Training Criterion Rather than a Prediction Criterion. Int. J. Neural Syst. 1997, 8, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Shi, Y.; Qi, Y.; Ma, C.; Yuan, R.; Wu, D.; Shen, Z.J. A Practical End-to-End Inventory Management Model with Deep Learning. Manag. Sci. 2022, 69, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, M.; Gao, Y. Integrated scheduling of wind farm energy storage system prediction and decision-making based on deep reinforcement learning. Power Syst. Autom. 2021, 45, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.W.; Qi, C.; Wei, Y.C.; Li, B.; Zhu, S. Review on Data-based Decision Making Methodologies. Acta Autom. Sin. 2009, 35, 820–833. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; He, D.; Wang, G.; Li, J.; Xie, Y. Big data intelligent decision making. J. Autom. 2020, 46, 878–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lean, Y. Research on theory and method of prediction and decision optimization based on artificial intelligence. Manag. Sci. 2022, 35, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Mao, Y.; Wang, S. Prediction driven optimization: Uncertainty, statistical theory, and management applications. Chin. Sci. Found. 2024, 38, 750–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotary, J.; Fioretto, F.; Van Hentenryck, P.; Wilder, B. End-to-end constrained optimization learning: A survey. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.16378. [Google Scholar]

- Mandi, J.; Kotary, J.; Berden, S.; Mulamba, M.; Bucarey, V.; Guns, T.; Fioretto, F. Decision-focused learning: Foundations, state of the art, benchmark and future opportunities. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2024, 80, 1623–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadana, U.; Chenreddy, A.; Delage, E.; Forel, A.; Frejinger, E.; Vidal, T. A survey of contextual optimization methods for decision-making under uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 320, 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajemisin, A.O.; Maragno, D.; den Hertog, D. Optimization with constraint learning: A framework and survey. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 314, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Wen, Z. Optimization: Modeling, Algorithms, and Theory; Higher Education Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bennouna, A.; Van Parys, B.P. Learning and decision-making with data: Optimal formulations and phase transitions: A. Bennouna, BPG Van Parys. Math. Program. 2025, 1–93, Article in advance. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Hanasusanto, G.A. A decision rule approach for two-stage data-driven distributionally robust optimization problems with random recourse. Inf. J. Comput. 2024, 36, 526–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Chu, Z.; Sun, M.; Teng, F. Risk-Aware Objective-Based Forecasting in Inertia Management. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 4612–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tian, D.; Lin, C.; Yin, H. Survey of end-to-end autonomous driving systems. J. Image Graph. 2024, 29, 3216–3237. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Wu, P.; Chitta, K.; Jaeger, B.; Geiger, A.; Li, H. End-to-end autonomous driving: Challenges and frontiers. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 10164–10183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, S.; Eiron, N.; Long, P.M. On the difficulty of approximately maximizing agreements. J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 2003, 66, 496–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Grigas, P. Risk bounds and calibration for a smart predict-then-optimize method. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 22083–22094. [Google Scholar]

- Ho-Nguyen, N.; Kilinç-Karzan, F. Risk Guarantees for End-to-End Prediction and Optimization Processes. Manag. Sci. 2022, 68, 8680–8698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder, B.; Dilkina, B.; Tambe, M. Melding the Data-Decisions Pipeline: Decision-Focused Learning for Combinatorial Optimization. In Proceedings of the 33rd AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence/31st Innovative Applications of Artificial Intelligence Conference/9th AAAI Symposium on Educational Advances in Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; pp. 1658–1665. [Google Scholar]

- Mandi, J.; Demirovi, E.; Stuckey, P.J.; Guns, T. Smart predict-and-optimize for hard combinatorial optimization problems. In Proceedings of the National Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Chennai, India, 27–28 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Loke, G.G.; Tang, Q.; Xiao, Y. Decision-Driven Regularization: A Blended Model for Predict-then-Optimize. Available SSRN 3623006. 2022. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Decision-Driven-Regularization-A-Blended-Model-for-Loke-Tang/df9b74cf4b2d7b9642d8bbb585eb086316953df2 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Elmachtoub, A.N.; Liang, J.C.N.; McNellis, R. Decision Trees for Decision-Making under the Predict-then-Optimize Framework. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Electr Network, Vienna, Austria, 13–18 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Gupta, V. Decision-focused learning with directional gradients. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 79194–79220. [Google Scholar]

- Schutte, N.; Postek, K.; Yorke-Smith, N. Robust losses for decision-focused learning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.04328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, A.; Kwon, R.H. Efficient differentiable quadratic programming layers: An ADMM approach. Comput. Optim. Appl. 2023, 84, 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, B.; Kolter, J.Z. OptNet: Differentiable Optimization as a Layer in Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A.; Amos, B.; Barratt, S.; Boyd, S.; Diamond, S.; Kolter, J.Z. Differentiable convex optimization layers. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33rd Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, D.; Fung, S.W.; Heaton, H. Differentiating through integer linear programs with quadratic regularization and davis-yin splitting. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.13395. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, H. Decision-focused graph neural networks for graph learning and optimization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Data Mining (ICDM), Shanghai, China, 1–4 December 2023; pp. 1151–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Shi, Y.; Wang, J.; Tuan, H.D.; Poor, H.V.; Tao, D. Alternating differentiation for optimization layers. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2210.01802. [Google Scholar]

- Guler, A.U.; Demirovic, E.; Chan, J.; Bailey, J.; Leckie, C.; Stuckey, P.J. Divide and learn: A divide and conquer approach for predict+ optimize. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.02342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donti, P.L.; Amos, B.; Kolter, J.Z. Task-based End-to-end Model Learning in Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Oroojlooyjadid, A.; Snyder, L.V.; Takac, M. Applying deep learning to the newsvendor problem. Iise Trans. 2020, 52, 444–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Gao, J.B. Assessing the Performance of Deep Learning Algorithms for Newsvendor Problem. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Neural Information Processing (ICONIP), Guangzhou, China, 14–18 November 2017; pp. 912–921. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, L.; Cui, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Feng, R.; Prakash, B.A.; Zhang, C. End-to-end stochastic optimization with energy-based model. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 11341–11354. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Liu, D.; Yang, C. Model-free unsupervised learning for optimization problems with constraints. In Proceedings of the 2019 25th Asia-Pacific Conference on Communications (APCC), Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 6–8 November 2019; pp. 392–397. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.; Wang, K.; Wilder, B.; Perrault, A.; Tambe, M. Decision-focused learning without decision-making: Learning locally optimized decision losses. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 1320–1332. [Google Scholar]

- Mandi, J.; Bucarey, V.; Mulamba, M.; Guns, T. Decision-Focused Learning: Through the Lens of Learning to Rank. In Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Baltimore, MD, USA, 17–23 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S.; Wang, P.; Abbas, K. A survey on deep learning and its applications. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2021, 40, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solozabal, R.; Ceberio, J.; Takáč, M. Constrained combinatorial optimization with reinforcement learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.11984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Shah, S.; Chen, H.; Perrault, A.; Doshi-Velez, F.; Tambe, M. Learning MDPs from Features: Predict-Then-Optimize for Sequential Decision Problems by Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2106.03279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, B.; Tian, W.; Xia, C.; Qin, W. Solving capacitated vehicle routing problems based on end to end deep reinforcement learning. Appl. Res. Comput. 2024, 41, 3245–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.; Feng, Z. Exploration approaches in deep reinforcement learning based on uncertainty: A review. Appl. Res. Comput. 2023, 40, 3201–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besbes, O.; Mouchtaki, O. How big should your data really be? Data-driven newsvendor: Learning one sample at a time. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 5848–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossen, J.; Farquhar, S.; Gal, Y.; Rainforth, T. Active surrogate estimators: An active learning approach to label-efficient model evaluation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 24557–24570. [Google Scholar]

- Settles, B. Active Learning Literature Survey; University of Wisconsin-Madison, Department of Computer Sciences: Madison, WI, USA, 2009; Available online: http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1793/60660 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Liu, M.; Grigas, P.; Liu, H.; Shen, Z.-J.M. Active learning in the predict-then-optimize framework: A margin-based approach. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.06584. [Google Scholar]

- Basciftci, B.; Ahmed, S.; Shen, S. Distributionally robust facility location problem under decision-dependent stochastic demand. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 292, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Z. Solving data-driven newsvendor pricing problems with decision-dependent effect. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.13924. [Google Scholar]

- Alley, M.; Biggs, M.; Hariss, R.; Herrmann, C.; Li, M.L.; Perakis, G. Pricing for heterogeneous products: Analytics for ticket reselling. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2023, 25, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, M.S.; Vandenberghe, L.; Boyd, S.; Lebret, H. Applications of second-order cone programming. Linear Algebr. Appl. 1998, 284, 193–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferber, A.; Wilder, B.; Dilkina, B.; Tambe, M. Mipaal: Mixed integer program as a layer. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 1504–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Vlastelica, M.; Paulus, A.; Musil, V.; Martius, G.; Rolínek, M. Differentiation of blackbox combinatorial solvers. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.02175. [Google Scholar]

- Berthet, Q.; Blondel, M.; Teboul, O.; Cuturi, M.; Vert, J.-P.; Bach, F. Learning with differentiable pertubed optimizers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 9508–9519. [Google Scholar]

- Mandi, J.; Guns, T. Interior point solving for lp-based prediction+ optimisation. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 7272–7282. [Google Scholar]

- Fioretto, F.; Van Hentenryck, P.; Mak, T.W.; Tran, C.; Baldo, F.; Lombardi, M. Lagrangian duality for constrained deep learning. In Proceedings of the Joint European Conference on Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases, Ghent, Belgium, 14–18 September 2020; pp. 118–135. [Google Scholar]

- Nandwani, Y.; Pathak, A.; Singla, P. A primal dual formulation for deep learning with constraints. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32. Available online: https://papers.nips.cc/paper_files/paper/2019/hash/cf708fc1decf0337aded484f8f4519ae-Abstract.html (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Kervadec, H.; Dolz, J.; Yuan, J.; Desrosiers, C.; Granger, E.; Ayed, I.B. Constrained deep networks: Lagrangian optimization via log-barrier extensions. In Proceedings of the 2022 30th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Belgrade, Serbia, 29 August–2 September 2022; pp. 962–966. [Google Scholar]

- Donti, P.L.; Rolnick, D.; Kolter, J.Z. DC3: A learning method for optimization with hard constraints. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.12225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmachtoub, A.N.; Lam, H.; Lan, H.; Zhang, H. Dissecting the Impact of Model Misspecification in Data-driven Optimization. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.00626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Traditional Methods | Past Data-Driven Methods | End-to-End Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core objective | Separate prediction and optimization | Data-driven prediction + independent optimization | Directly optimize decision outcomes |

| Technical means | Statistical model + mathematical programming | Machine learning prediction + traditional model | Decision-making participation feedback dissemination |

| Dealing with uncertainty | Dependent distribution assumption | Data-driven ambiguity sets | Learning decision-making strategies |

| Issues of decision dependence | Inapplicable | Partially supported (complex modelling required) | Supported (e.g., pricing affects demand) |

| Case advantage | Quick solutions to simple problems | High-dimensional covariate scenarios (such as e-commerce demand forecasting) | Complex decision chains (inventory, path planning) |

| Studies | Yu. et al. (2020) [7] | Yu. (2022) [8] | Wang, et al. (2024) [9] | Kotary et al. (2021) [10] | Mandi et al. (2024) [11] | Sadana et al. (2025) [12] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field Positioning | automatic | management science | Statistics management | optimization algorithm | machine learning | operations research (OR) |

| Core issues | Big Data-Driven Decision Making with Uncertainty | Mechanisms of paradigm shift in decision-making driven by artificial intelligence | Statistical Theory of Prediction-Driven Optimization | End-to-end portfolio optimization | Classification of Decision Focused Learning techniques | A Unified Framework for Contextual Optimization Methods |

| core framework | Five-aspect analysis:

| Key research directions:

| Two-tier architecture:

| Differentiability based processing approaches:

| DFL quadruple taxonomy:

| The triple paradigm of contextual optimization:

|

| theoretical contribution | Characteristics of big data decision-making are summarized | Proposing an AI-enabled decision-making paradigm in management science | A unified theory of statistical performance guarantees for stochastic and distributionally robust optimization | Research into the theory of constraint-optimized differentiable programming | First systematic classification of DFL techniques with applications and evaluations | Establishment of a unified terminology system for prediction-optimization in the OR/MS field |

| limitations | Quantitative theories of decision quality not addressed | Lack of specific algorithmic implementation details | Uncovered combinatorial optimization problems | Dependency on specific structural elements | Unresolved large-scale issues scalability | Not delved deeply into machine learning theory |

| Dominant application areas | Industrial control systems | Strategic decision-making for enterprises | Operations management (om) | Embedded system | Combinatorial optimization problem | Service system |

| Solutions | Constructing Closed-Loop Losses | Constructing a Differentiable Optimization Layer | Parameterized Representation of Optimization Problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| feature | Connect the two stages into a decision-centered whole through a loss function | Embedding the optimization problem solution into a layer of the network | Parameterizing optimization problems for learning with data |

| advantage | Easy to operate, low computational cost | The optimization process is highly interpretable; Gradient backpropagation is precise. | It is independent of the structure of optimization problems. Exhibits strong dynamic adaptability |

| shortcoming | Relying on linear objectives and training requirements to solve optimization problems | High computational cost and non-convex constraints can lead to infeasible solutions | Lack of interpretability, requiring a large amount of data |

| data requirements | A small amount (input, optimize problem parameters) pairs | Medium (input, constraint parameters) pairs | High (input, optimal solution) pairs |

| convexity hypothesis | strong | strong | weak |

| decision label | none | none | tall |

| interpretability | mid | tall | low |

| applicable scenarios | Linear programming, low real-time performance, cost-sensitive scenarios | Convex optimization, high interpretability, precision first scenario | Non-convex/discrete optimization, high dynamic scenarios |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, W.; Li, G. A Review of End-to-End Decision Optimization Research: An Architectural Perspective. Algorithms 2026, 19, 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010086

Zhang W, Li G. A Review of End-to-End Decision Optimization Research: An Architectural Perspective. Algorithms. 2026; 19(1):86. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010086

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Wenya, and Gendao Li. 2026. "A Review of End-to-End Decision Optimization Research: An Architectural Perspective" Algorithms 19, no. 1: 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010086

APA StyleZhang, W., & Li, G. (2026). A Review of End-to-End Decision Optimization Research: An Architectural Perspective. Algorithms, 19(1), 86. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010086